Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: No Exit Press

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

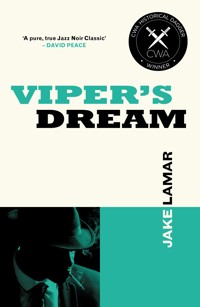

Winner For fans of Colson Whitehead and Chester Himes, Viper's Dream is a gritty, daring look at the vibrant jazz scene of mid-century Harlem, and one man's dreams of making it big and finding love in a world that wants to keep him down. 1936: Clyde 'The Viper' Morton boards a train from Alabama to Harlem to chase his dreams of being a jazz musician. When his talent fails him, he becomes caught up in the dangerous underbelly of Harlem's drug trade. In this heartbreaking novel, one man must decide what he is willing to give up and what he wants to fight for. 'Viper's Dream is one Long High, sweeping us through Harlem from the 1930s to the 1960s on riffs of melancholy poetry cut through with the hardboiled beats of gangsters and their streets, leaving us hooked on a pure, true Jazz Noir Classic' - David Peace 'Viper's Dream, with its African-American gangster anti-hero, is reminiscent of Ray Celestin's jazz-oriented thrillers and similarly introduces real jazz greats into a fascinating melange' - The Financial Times 'Wonderful writing. From the first lines, you're there. You can almost see sweat flying off the strings of a slapped upright bass. You've been listening to the music, reading the book, for hours now - and it's still full of surprises' - James Sallis

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 248

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Critical Acclaim for Jake Lamar

‘A fearless young talent to keep your eye on’ – Entertainment Weekly

‘This one is a gem not just for its plotting but for the extremely likable character of Jenks, who lives in a world of perpetual perplexity where music is the only thing he understands well. Mr Lamar’s love of Paris and his understanding of its ways add to the delight’ – Washington Times on Rendezvous Eighteenth

‘The author casts a tough, critical eye on his cast of mostly black middle-class expatriate Americans, whose interactions he so deftly depicts… Mainstream readers fond of Paris should feel fully satisfied’ – Publishers Weekly on Rendezvous Eighteenth

‘Always a witty and astute social observer, Jake Lamar illuminates the interaction of French locals with Americans abroad, some of them on the lam, in a suspenseful and funny thriller set in the seamy, particularly fascinating Eighteenth Arrondissement of Paris’ – Diane Johnson, author of Le Divorce, Le Mariage, and L’Affaire, on Rendezvous Eighteenth

‘A page-turner of a murder mystery with a clear, breezy style. The book is also a wicked black comedy in both senses of the phrase – it’s both caustically funny and a shrewd take on racial politics’ – New York Times Book Review on If 6 Were 9

‘Maybe he’s feeling the shade of the great Chester Himes, because this novel has wit and sparkle, to say nothing of fabulous characters’ – Globe and Mail on If 6 Were 9

‘Lamar is a skilled tactician… The situations and relationships are believable and sharp’ – Washington Post Book Worldon Close to the Bone

‘Lamar skillfully weaves the romantic with the political, and the personal with the societal’ – Mademoiselle on Close to the Bone

‘A compelling, controversial political thriller, part A Clockwork Orange, part The Manchurian Candidate’ – Kirkus Reviews on The Last Integrationist

‘A crackling page-turner… Jake Lamar has produced a thriller of ideas… A kind of racial 1984’ – Vogue, on The Last Integrationist

‘A knockout debut. The recollection of a well-to-do African-American childhood marred by family discord is as taut as the spriest novel and as revealing as many a hefty sociological tome’ – Seattle Times on Bourgeois Blues

‘On this subject it’s a relief to read somebody who doesn’t consider it their first task to make you feel at ease’ – Newsday, on Bourgeois Blues

‘Dickensian in its power’ – Atlanta Journal Constitution on Bourgeois Blues

For Dorli

‘It’s like an act of murder; you play with intent to commit something.’

Duke Ellington

Chapter One

‘Tell me, Viper,’ the Baroness asked, ‘what are your three wishes?’

I am speaking now of November 1961. It was ’round midnight at the Cathouse. There must have been about twenty jazzmen scattered around the place, talking and laughing, drinking and jiving, eating, smoking, toying with their instruments. One could hear the distant plucking of a bass coming from one corner of the house, the errant honk of a saxophone echoing from another, the playful tickling of piano keys. And one could hear a cacophony of meowing, of purring, of hissing, of claws scratching at the furniture. The Cathouse was a double entendre, a home away from home for the two-legged black cats of the jazz world and the actual home of more than a hundred furry felines.

The Cathouse belonged to the Baroness Pannonica de Koenigswarter, ‘Nica’ to her many friends. She was a Rothschild heiress, a blue-blooded European who had parachuted into the New York jazz scene and become a sort of patron, protectress, groupie of the bebop generation. She used to throw all night party-jam sessions in various luxury Manhattan hotels. It was fun times till Charlie Parker dropped dead in the Baroness’s suite at the Stanhope. Management was not pleased. That was six years ago. The ensuing scandal made it impossible for Nica to find a place in the city that suited her desire for space and all-night jams. So she bought a Bauhaus-style edifice in Weehawken, New Jersey, just across the bridge from Manhattan, with huge picture windows offering a spectacular view of the glittering metropolis. Thelonious Monk more or less lived at the Cathouse. And the guest list of musicians who passed through, stopped by or stayed a while included the likes of Duke, Satchmo, Dexter, Dizzy, Mingus, Miles, Coltrane… I could go on. Lots of folks you’ve heard of. Plenty more you haven’t. This story is about someone you probably haven’t heard of. He wasn’t a musician but he was as welcome at the Cathouse as any of the jazzmen. Clyde Morton was his actual name. But just about everybody called him The Viper.

You may not have heard of him but you’ve most likely seen him, in grainy black-and-white photographs, going back to the 1930s. He’s often there, hovering in the shadows, at jazz clubs, recording sessions, impromptu jams, always deep in the background, dressed in a sharp suit, with a sly smile, pencil-thin moustache, sleek, processed hair. You’ve seen him there at the after-parties, sitting at the far corner of the table, behind the half-empty liquor bottles, the overflowing ashtrays, and plates filled with chicken bones. That look of his. Languid yet dangerous. He sits there, a stillness, a watchfulness about him. There was indeed something reptilian about this man. Everybody was scared of Clyde ‘The Viper’ Morton. Except for maybe the Baroness.

‘Achoo!’

‘Viper, are you allergic?’

‘Slightly.’

‘I never noticed before.’

‘It’s all right, Nica.’

‘What a surprise. I didn’t think you had any weaknesses at all. Are your eyes watering?’

‘I’m fine, Nica.’

‘Viper, are you crying?’

‘No, it’s just the cats.’

‘Let me get you a drink. Bourbon on the rocks, yes?’

‘Yes.’

No, the Viper was no musician. He had wanted to be one. He had the desire. All he lacked was the talent. But he figured if he couldn’t make music himself, he’d help those who could by supplying them with some of the inspiration they needed, the elixir of creativity. On this night at the Cathouse, the jazzmen greeted the Viper with the usual gratitude and respect.

‘Hey, Viper, how ya doin’, my man? Thanks for that last score.’

‘Viper, you got any of that go-o-o-od shit for me tonight?’

‘Yeah, man, I don’t know if it was the Californian or the herb from Indochina but I was so high at that gig at the Vanguard last week – I ain’t never played like that. Thank you, Viper!’

Just about everybody at the Cathouse that night was partaking of the Green Lady. The sweet smell of marijuana perfumed the air. And Clyde Morton had provided all of it, if not directly, then through his network of dealers – every ounce, every grain.

‘Yo, man, you gonna share that joint or what?’

‘Take another hit, then try it in B flat.’

‘No, no, the way Pops plays it, the trumpet squeeeeeeals at the end. You gotta make it squeal…’

The Viper leaned back on Nica’s living room couch, languid and watchful, taking in the scene. No one, aside from the Baroness, had noticed anything strange about the Viper tonight. But he was indeed fighting back tears. Twenty-five years in this vocation. And until this night, in November 1961, he had killed only two people. Tonight was the Viper’s third kill. For the third time in twenty-five years, he had taken a person’s life. But this was the first time he had regretted it.

One hour earlier, Clyde Morton stood in a phone booth on Lenox Avenue and dialed the number of his old pal the cop.

‘Hello, Detective Carney.’

‘Viper, is that you?’

‘Get a patrol car over to Yolanda’s apartment. And an ambulance.’

‘Is there somebody dead?’

‘Yeah.’

‘I can give you three hours, Viper, no more.’

‘Thanks, Carney. I guess.’

‘My advice is: get out of the country. Go to Canada. Or Mexico. Or hop on a plane to Europe. But do it now, Viper. Because in three hours, I’m comin’ after you. Three hours. That’s all I can give you.’

Click. Dial tone.

Viper felt dizzy as he stepped out of the stale, muffled air of the phone booth and into the neon cacophony of Lenox Avenue. The full force of what had happened, of what he had done, of his crime, his primal sin, seemed to seep into his consciousness, like a drug taking effect. His vision blurred as tears stung his eyes. He had a dream-like sensation, not of his life flashing before his eyes but more a feeling of his whole past washing over him. He took in the scene before him, the febrile, sulfurous boulevard he loved. He felt the chill and the drizzle. But still the avenue was bristling with the life of the night. Traffic and chatter. Folks rushed down the street, spilled out of bars and clubs. A restaurant door swung open and Viper inhaled a mouth-watering aroma, like a gust of spiced wind, smelling sublimely of kitchen grease, of chicken frying crispy in a skillet, of robust barbecue sauce, and earthy collard greens. Down home cookin’ folks used to call it. Soul food, in the new argot. Black folks’ cuisine. The scent of home. His mama’s kitchen, in Meachum, Alabama. Relocated to the capital of Black America.

‘Black people need to wake up!’ Viper glanced at the clean-cut young man standing on a stepladder at the corner, wrapped in a black overcoat, embroidered skull cap on his head, exhorting the passers-by who ignored him. ‘America is not ours. This land is not our land. And it will never be our land, even after our ancestors spent three hundred years slaving on it. There is no American Dream for the black man. Wake up from your dream! Recognize that Africa is our Black Motherland! We need to go home – to Mother Africa!’

The Viper couldn’t help but smirk, even as he fought back tears. He had been hearing the same speech from the same street corners for a quarter of a century, since the very day he arrived here, at the center of the Afro-American universe. Harlem. As he stood on loud, brazen Lenox Avenue, nearly swaying from the shock of what had happened tonight, the night of his third murder, Viper knew this might be the last time he ever saw her, his sweet bitch Harlem.

‘We don’t even know our history,’ the smooth-featured young man in the embroidered skull cap shouted as crowds bustled past him in the light, spitty rain. ‘The black man has lost touch with his past!’

Maybe it was true what the young brother said, Viper thought, even as he felt his own past crashing down on him in waves. Lenox Avenue seemed to swirl.

Haarlem. With two A’s. It was Mr O who first told young Clyde Morton of the original spelling of the place. New York was a tribal town, Mr O had told Clyde, before he became known as The Viper. The grassy plains of northern Manhattan had been populated first by indigenous Algonquin tribes. In the seventeenth century, Dutch tribes arrived, seized the land and named the region after a city in the Netherlands. It remained mostly farmland until the mid-nineteenth century when tribes of aristocratic white New Yorkers, mostly of British and Protestant descent, built mansions in the countryside, eager to escape the congestion of Lower Manhattan. Equestrians raced horses along rural Harlem Lane. Gentlemen in top hats and ladies holding parasols gathered on the banks of the Harlem River to watch weekend boat parades. Then came the Jewish tribes and rapid urbanization, the construction of row houses and tenements. At the beginning of the twentieth century, the Italian tribes took over Harlem. ‘Little Italy’ was up North before it was recreated in lower Manhattan. Next came the great migration of black people escaping the Deep South. Clyde Morton was one of them. Latino tribes arrived and settled in the east, in what would become known as Spanish Harlem. But as far as Viper Morton was concerned, the true Harlem, the pulsating heart of the place, was black.

‘The great Marcus Garvey was right,’ the young man in the skull cap cried. ‘We need to go back to Africa!’

Viper was always a bit puzzled by that phrase. How could you go back to someplace you had never been? Detective Red Carney had just urged him to flee to Canada, or Mexico, or Europe. Maybe, Viper wondered, he should catch a plane to Nairobi.

That was when the Baroness pulled up in her silver Bentley.

‘Viper, you look so forlorn.’

She sat behind the wheel, a cigarette holder clenched between her teeth. Thelonious Monk sat beside her, staring into space, a silk Chinese beanie on his head.

‘Maybe I’ve been waiting for you, Nica,’ the Viper said.

‘We’re going to my place. Join us.’

Viper slid into the backseat. ‘Hey, Monk.’

‘What’s up, Viper?’ the pianist growled.

Everybody knew Monk was the top cat in the Cathouse. On this chilly, drizzly Monday night, still sporting his black silk Chinese beanie, Thelonious sat in an armchair in the corner of Nica’s living room. Clearly, he wasn’t in the mood for playing the piano. Or for smoking, or talking to anybody else. He just sat in the corner, glowering benignly.

The Cathouse was where Viper decided to stay. In another two hours, Red Carney would come looking for him. He would have to be ready. He knew that this night, the night of his third murder, might be the last night of his own life.

‘Here’s your bourbon, Viper.’

‘Thanks, Nica.’

‘May I ask you a question?’

‘That depends.’

‘If you were given three wishes, to be instantly granted, what would they be?’

‘Are you messing with me, Baroness?’

‘I’m entirely serious. It’s my new thing. I ask this question of everyone. Well, everyone interesting. And I write down their answers.’

‘You write them down?’

‘Or you can write them down yourself.’

‘Why?’

‘For posterity, of course. Come on, indulge me. Tell me, Viper, what are your three wishes?’

‘Do it, Viper!’ The piano player, Sonny Clark, had just sauntered over, high as a kite. ‘It’s fun. Nica asked me last night.’

‘Yeah, Sonny,’ Viper said, ‘and what were your three wishes?’

‘One: Money. Two: All the bitches in the world. And three: All the Steinways!’

Sonny, Viper and Nica all laughed.

‘All right, Baroness, let me think about it.’

‘Here’s a notepad, and a pencil. Play along, Viper. You might be surprised by your own wishes.’

Viper decided to take the question seriously. He sat with the notepad and pencil and glass of bourbon on the coffee table in front of him. He pulled out a joint and fired it up. First time he’d gotten high in a year or more. He took a long drag, exhaled slowly. He gave in to the sensation he’d felt on Lenox Avenue. He let himself be carried, swept away, by the waves of the past he felt washing over him. He closed his eyes and imagined he was back there, back home, in Meachum, Alabama, 1936.

‘All aboard for New York City!’ the conductor hollered.

Clyde Morton had been sitting beside his fiancée Bertha on a bench in the Colored Waiting Room of the train station. He rose and grasped his suitcase in one hand, his trumpet case in the other.

‘Is you really leavin’ me, Clyde?’ Bertha said, her voice quivering.

‘I ain’t leavin’ you, Bertha. I’m leavin’ Meachum, Alabama. I’m leavin’ the South.’

‘But we got it good here, Clyde. We both got our high school diplomas. We both got good jobs at the cotton mill.’

‘That ain’t enough for me.’

‘But I love you, Clyde. We engaged to be married. My love ain’t enough for you?’

‘All aboard for New York City!’ the conductor hollered again.

‘I got the gift of music, Bertha. Uncle Wilton told me so.’

‘But, Clyde, your Uncle Wilton is a hobo. He ain’t nothin’ but a drunk and a thief and a liar!’

‘But he sho’ can play guitar, you gotta admit it.’

‘He plays the blues, Clyde. It’s the devil’s music.’

‘And I’m gonna play jazz, Bertha. That’s even worse, more sinful.’

Clyde headed out to the platform. Bertha ran after him.

‘But, Clyde, what if you ain’t that good, what if you don’t make it?’

‘I am that good. I know I’ll make it.’

‘Don’t leave me, Clyde!’

‘All aboard! Last call for New York City!’

Bertha was clinging to Clyde now, tearing at his clothes as he strode across the platform toward the train, trying to pull him back into the Colored Waiting Room.

‘I gots to go, Bertha! Turn me loose!’

‘Don’t leave me, Clyde!’ she screamed, suddenly hysterical. ‘Please don’t leave me, Clyde! I’ll kill myself if you leave me!’

‘Lemme go!’ Clyde shoved his fiancée and she fell to her knees.

‘I swear to God, I’ll kill myself!’ Bertha crawled desperately after Clyde, grabbed his leg.

‘Damn it, Bertha, let me go!’

Clyde managed to tear away and step up into the train car. The steel door slammed shut behind him. He looked out the window at Bertha, crumpled on the platform, wailing in anguish. ‘I’ll kill myself!’

Clyde heard the chugging of the engine, the screech of the steel wheels on the railroad tracks. As the train pulled away from the station, he looked out the window at his fiancée, still wailing, her voice fading in the distance. ‘Don’t leave me, Clyde! I’ll kill myself! I’ll kill our –’

The train whistle drowned out Bertha’s voice. Clyde hadn’t heard the last word she screamed. But he knew what it was.

‘Last stop,’ the conductor cried, ‘New York City!’

After arriving at Penn Station, Clyde Morton took his first subway ride, hopping aboard the A train. He emerged from underground on a bright, crisp afternoon in September 1936 and stepped into the glory that was Harlem. He was staggered by the noise, the energy, and the sight of all those black folks, black folks from all walks of life: businessmen, businesswomen, mothers pushing baby carriages, street-corner preachers, bums and winos, shady ladies loitering in doorways, proper ladies who looked like schoolteachers, fellas playing dice on the corner – and even a black policeman! He walked around in a daze, his suitcase in one hand, his precious trumpet, in its hard case, tucked under his arm, feeling like a country-ass fool, his eyeballs popping and his mouth hanging open. The biggest city he’d ever seen before was Birmingham, Alabama.

As night fell he just kept walking, around and around, up Lenox Avenue, down Seventh Avenue and back up Lenox again. He saw with his own eyes places he’d only heard about on the radio: The Apollo Theater, The Savoy Ballroom, Smalls’ Paradise. And other places he’d never heard of at all but would someday come to know well: The Red Rooster, Gladys’ Clam House, Tillie’s Fried Chicken Shack. He gaped at the swanky white couples pulling up in their fancy cars, for a night of uptown adventure, and black couples every bit as swanky, striding right past the white folks, without a hint of deference. The colored folks even had an air of superiority, a proprietary attitude. This was Harlem. This was our turf.

He checked into a cheap flophouse and lay in his narrow bed, wide awake, listening to the street sounds that seemed to go on all night. He didn’t know when he fell asleep but he woke up, with a start, to daytime noises, trucks and schoolchildren, the sun streaming through the dirty window. It was noon. Clyde went to the corner diner, had a breakfast of ham and eggs and grits, then walked the streets, holding his trumpet under his arm, certain that destiny awaited him. And there it was. He found himself standing in front of a club he had passed by the night before: it was called Mr O’s. And there, written on a standing chalkboard in front of the entrance: TRUMPET PLAYER WANTED. AUDITION INSIDE.

In a way, he could hardly believe it. But, at the same time, he had been expecting just this sort of luck. He entered the club, Mr O’s, filled with an uncanny sense that he was stepping into his future.

‘Hello…?’ Clyde called out. ‘Anybody here…? Hello…?’

The club was dark. He could make out the silhouettes of chairs stacked on tables. Suddenly, a light snapped on in what seemed to be the kitchen backstage. More lights flickered on and Clyde found himself standing in the middle of a dance floor. A big, bearish black man emerged from the hallway. He had a round, jolly face, wore his hat pushed back on his head, the front brim snapped up.

‘Hey there, youngblood. I’m Pork Chop Bradley.’

‘You’re Pork Chop Bradley?’ Clyde said. ‘The bass player?’

‘You’ve heard of me?’

‘Yes, suh!’

‘I’ve just been hired as the band leader here at Mr O’s. You new in town?’

‘Just arrived yesterday, suh.’

‘Stop callin’ me “sir.” I ain’t your daddy or a cop.’

‘Yes, suh! I mean, OK, sorry, Mr Pork Chop, I mean, Mr Bradley.’

Pork Chop smiled. He seemed both kindly and bemused. ‘Where you from, Country?’

‘Alabama.’

‘I’m from Arkansas myself. But I been up here in the big city ten years. Playing in Harlem bands. Is that your dream, Country? To play in a Harlem band?’

‘That’s my dream.’

‘How old are you?’

‘Nineteen.’

‘What did you say your name was?’

‘I didn’t. Sorry. I’m Clyde Morton.’

‘All right, Clyde. Enough of the niceties. Get that horn out of its case. You know “Stardust”?’

‘I sure do.’

‘Play it.’

Clyde closed his eyes as he played. At first, he felt like he was wrestling with his horn, like it was a giant, slimy, man-sized fish. He was splashing around in the shallow water, trying to haul the beast to shore. Slowly, the flailing stopped. He had subdued the slippery thing. And so he felt in control of his horn. Finally. Yes, he knew Hoagy Carmichael’s ‘Stardust’. He knew the Louis Armstrong version, had heard it over and over again on his Uncle Wilton’s phonograph. He’d studied it. And standing there, in Mr O’s nightclub, auditioning for Pork Chop, young Clyde Morton played as close to Satchmo as he knew he could ever get.

‘OK, OK, stop,’ Pork Chop shouted over Clyde’s blowing. ‘Stop right there, son, stop! Stop!’

Clyde lowered the horn from his lips, baffled. ‘I was just in the middle of the song,’ he said.

‘No, you’re done. Clyde, I’m sorry, that was dreadful.’

‘Huh? What?’

‘Is this is a practical joke? Did Mr O send you here as a prank? Is that it?’

‘Uh, no, Mr Pork Chop, I’ve never met Mr O.’

‘Sweet mother of Jesus. You really were auditioning? That really is the way you play? That was the worst shit I ever heard in my life.’

‘I, I did my best… I could try again…’

‘No, son, there’s no point. I mean, I can hear it. Not only are you not a trumpet player, you’re not a musician at all. Who told you you were?’

‘My Uncle Wilton,’ Clyde said, his voice cracking. ‘Down in Alabama.’

‘I hate to break it to you, son,’ Pork Chop said softly.

‘He’s gonna be so disappointed.’

‘Don’t cry, son. You were just dreaming the wrong dream.’

‘What am I gonna do now?’

Pork Chop gave Clyde a long look, kindly and bemused. ‘Do you know Mary Warner?’ he asked.

‘Mary Warner?’ Clyde said, swallowing hard, choking back tears. ‘Who’s she?’

Pork Chop chuckled. ‘Let’s go up to the rooftop. I’ll introduce you.’

Naturally, Clyde had thought Pork Chop was talking about a chick. Some prostitute named Mary Warner. As they climbed the six flights of stairs, he wondered why she would be on the rooftop. But he didn’t give it much thought. He was still stunned by Pork Chop’s opinion of his talent – or the lack thereof. He knew he was right. Clyde had been dreaming the wrong dream. He felt he might swoon when they stepped out onto the rooftop. He’d never been up so high in his life. The street noise below sounded somehow unreal. He heard pigeons flapping their wings, burbling. But he didn’t see any prostitute.

Pork Chop pulled out a cigarette that he’d clearly rolled himself. Clyde watched as Pork Chop lit the cigarette, drew on it with a hissing sound, held the smoke in his lungs, then exhaled slowly. Clyde smelled a sweet yet peppery aroma, unfamiliar but appealing. He suddenly realized: This was reefer. He’d heard of it, yes, but he had never seen or smelled it before. Pork Chop held the cigarette out to him.

‘Meet Mary Warner, Clyde. Also known as marijuana. Is this your first time?’

‘It is.’

‘Take a drag, like you just saw me do.’

Clyde sucked hard on the joint: Ssssssssss…

Pork Chop said: ‘Welcome to the fraternity, Mr Clyde Morton. You ain’t no musician but now you’ll know what the jazzmen know. Mary Warner, she was there, in Storyville, New Orleans, when jazz was being born. All the original greats nursed at Mary Warner’s teat.’

It took a minute but the effect of the herb gradually kicked in. Now Clyde understood the expression he had heard when folks talked about reefer: Getting high. Standing on that rooftop in Harlem, watching the clouds drift by, he felt a dreamy elevation.

Pork Chop said: ‘Mary Warner is magic. I call it the elixir of creativity.’

Clyde took another hit. Ssssssss.

‘Hey, Clyde,’ Pork Chop said, with a laugh, ‘you gonna pass that stick back or what?’

Clyde laughed, too, handed Pork Chop back the joint.

When he had walked into Mr O’s nightclub just a little while earlier, Clyde had thought he was meeting his destiny: to be a professional musician. Turned out he was no musician. But he was right about the destiny part.

Pork Chop said: ‘Vipers. That’s what we lovers of herb call ourselves. ’Cause of that hissing sound you make when you take a drag on a joint. I can tell you’re a natural born viper, Clyde Morton.’

Clyde was soothed by the sound of Pork Chop’s voice. There was a serenity about this fat bass player in his battered fedora with the front brim turned up. Pork Chop took another couple of hits on the joint, passed it back to the initiate.

Clyde took a hit. He stared out at the Harlem skyline, hearing Louis Armstrong’s sublime rendition of ‘Stardust’ in his head, feeling newly awake, newly alive, tingly and alert. Yet cool, so cool, cool as could be.

‘Tell me, Mr Pork Chop Bradley: Where do you get a hold of this here Mary Warner?’

Pork Chop said: ‘From the owner of the nightclub. Mr O himself. Also known as Abraham Orlinsky. I’ll introduce you to him someday if you like. I reckon you ain’t goin’ back to Alabama?’

Ssssssss.

‘No, Pork Chop. I’m stayin’ right here.’

‘Welcome to Harlem, Viper Clyde.’

‘If you were given three wishes,’ the Baroness had asked, ‘to be instantly granted, what would they be?’

November 1961: the night of Clyde ‘The Viper’ Morton’s third murder. Viper was stoned. He sat in the Cathouse, a notebook and pencil in front of him, contemplating Nica’s question. He knew that in a couple hours’ time, he might be dead or on his way to prison. His pal the cop, Red Carney, had given him three hours to get out of town, to get out of the country. But here he sat, in the Baroness de Koenigswarter’s sprawling living room, amid the cats – the jazzmen and the felines – contemplating his three most precious wishes.

‘Don’t strain too hard, Viper,’ Nica said. ‘Write the first three things that come to your mind.’

‘I’m thinking, Nica,’ Viper said, a slight edge in his voice. ‘I’m thinking.’

‘Yes, of course, Viper,’ Nica said, suddenly a little nervous. ‘No pressure at all. Take your time.’

The doorbell rang.

‘Oh, a new arrival!’ the Baroness said, cutting a path through a writhing sea of cats, toward the front door.

The Viper was always a little suspicious of Nica. Ever since that night six years ago when Charlie Parker dropped dead in her suite at the Stanhope Hotel. They said it was a heart attack. Bird was thirty-four-years-old. But the coroner thought he was a man of sixty. That was how much damage he’d done to his body. Yeah, the great Charlie Parker technically died of a heart attack. But everybody knew it was heroin that killed him.

Now this is what you need to know about Clyde ‘The Viper’ Morton. Yes, he was a dealer of marijuana. But he could not abide heroin. He had never used it and he would never sell it. He forbade anyone who worked for him to sell it. Heroin was a poison. It was the opposite of herb. Marijuana aided the creation of jazz. Heroin was in the process of destroying jazz, by killing off its greatest artists. The Viper didn’t know if the Baroness de Koenigswarter had enabled Bird’s heroin abuse. But he did know that junk killed Bird, and Bird died in Nica’s hotel suite. The Viper had never seen anyone shooting up at the Cathouse. And no one would dare do it in his presence. Everybody knew the Viper was the man to see for marijuana. And everybody knew how he felt about heroin. They knew that if you wanted to deal that shit in the Viper’s sphere… he would kill you.

‘Clyde. Hey, Clyde.’

The Viper looked up and saw Pork Chop Bradley standing above him. He must have been the new arrival at the Cathouse. Pork Chop, his friend of twenty-five years. He was still fat, still wore his fedora with the front brim flipped up. But he was an old man now, and he stared down at the Viper with an infinite sorrow in his eyes. He knew what the Viper had done tonight. Knew the person he had killed.

‘Hello, Pork Chop.’

‘Lord have mercy, Clyde. I just came from Yolanda’s apartment.’

‘That’s what I figured.’

‘There was a lot of blood, Clyde. A lot of blood.’

Viper said nothing.

Pork Chop said: ‘How do you feel, man?’

‘How do you think I feel?’

‘Like you wanna die.’