0,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Reading Essentials

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

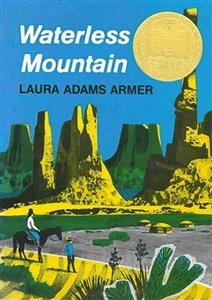

A poignant story of a young Navajo boy's spiritual odyssey and coming of age as a medicine man provides a vivid portrait of the beliefs, traditions, and lifestyle of the Navajo people. Winner of the 1931 Newbery Medal.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

Waterless Mountain

by Laura Adams Armer

First published in 1931

This edition published by Reading Essentials

Victoria, BC Canada with branch offices in the Czech Republic and Germany

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, except in the case of excerpts by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review.

When they came to the prehistoric cliff-dwelling high in the rocks, they hurried by.

Waterless Mountain

by Laura Adams Armer

ILLUSTRATED BY

Sidney ArmerandLaura Adams Armer

To

LORENZO HUBBELL

FOREWORD

N AUGUST 1924, my partner and I turned our two scraggly ponies and our treasured albino pack-horse loose in a corral at Oraibi and looked over the village. Hardly had we had time to buy a bottle of pop and roll a cigarette than we were informed that there was a lady artist in the schoolhouse, who had persuaded a Navaho medicine man to make a sacred sand painting for her and, contrary to the ceremonial laws, leave it undestroyed for people to look at. Incredulous, we went to see. The lady received us with some restraint, our aspect did not seem to charm her. Still, she admitted us to her temporary studio, and there was the sand painting, sure enough, complete even to the prayer-sticks around the edges, and many excellent pictures by herself to boot.

She grew more cordial after a while, and in talking with her about the Indians, we began to perceive the charm and sympathy which had won a medicine man to violate a dozen taboos for her. Finally she decided we were harmless. We invited her to our camp for a Navaho meal of goat’s ribs, and she, game lady, accepted. So we went and got ready.

We looked at ourselves as we had not in some weeks, and understood the coolness of our first reception—unshaven chins, the dust of the trail piled thick on filthy and tattered clothes, my partner’s golden hair turned a dull brown, we were the sorriest looking pair of tramps you ever saw. We got ourselves clean, Mrs. Armer came and shared our rather crude victuals, and friendship began.

Partly because of her paintings of the Navaho legends, in which the Indians saw an unusual insight and an expression of many things which they did not expect white people to understand, partly because she has been guided in her contacts by one of the wisest and most sympathetic of all the Navahos’ friends, and largely through her own personality, she has been able to come unusually close to these people in a very short time. Her knowledge of their real selves has enabled her to select a difficult theme for her book, the internal processes, the thoughts and feelings and growth of a Navaho boy who feels a vocation to become a medicine man. It is a daring subject for a white person to tackle, but within the limitations of a book for young people, Mrs. Armer has probably come as close to painting a true picture as anyone save a medicine man can do. Many readers will question the high religious ideas, the constant talk of beauty, the mysticism, that she ascribes to Younger Brother and his priestly Uncle; one can only say that, contrary to the general idea, many Indians are so.

February 1931

CONTENTS

CHAPTER

PAGE

I.

The Friends of Younger Brother

1

II.

Yellow Beak

9

III.

Spring Pollen

15

IV.

A New Song

23

V.

A Friend in Need

28

VI.

The First Spinner

33

VII.

The Young Daughter of Hasteen Sani

37

VIII.

The Trail of Beauty

43

IX.

The Basket Ceremony

49

X.

The Pack Rat

53

XI.

Christmas at the Trading Post

60

XII.

The Giant Dragon Fly

67

XIII.

Water from the Pool

74

XIV.

The Dance of the Maidens

80

XV.

The Dark Wind

86

XVI.

Westward Bound

91

XVII.

Adventures of the Pinto

99

XVIII.

Secrets to Share

106

XIX.

Beautiful under the Cottonwoods

111

XX.

The Western Mountain

118

XXI.

Exit the Pinto, Enter the Fire Horse

124

XXII.

By the Wide Waters of the West

130

XXIII.

Story of the Western Clans

138

XXIV.

The Movie Hero Speaks

144

XXV.

The House Dedication

148

XXVI.

On the Mountain Top

155

XXVII.

The Pack Rat’s Nest

164

XXVIII.

Four Pots in a Cave

170

XXIX.

Come on the Trail of Song

178

XXX.

The Sand Painting of the Whirling Logs

184

XXXI.

The Dance of the Yays

189

XXXII.

The Song in Their Hearts

194

XXXIII.

The Deep Below

203

XXXIV.

Carrying On

208

ILLUSTRATIONS

When they came to the prehistoric cliff-dwelling high in the rocks, they hurried by.

The Bumble Bee put his feet down in pollen.

They leapt and danced on the stone floor.

She ran east toward the dawn.

The first of the prancing ponies ran into the light of the campfire.

Mother took out the sheep.

Clouds of dust enveloped the boy and the pony, helpless before elemental fury.

Younger Brother wondered what had frightened them.

She threw the bow and arrows in with these words, “Tieholtsodi, monster of the waters, take these also”.

The Sun Bearer and the Turquoise Woman.

The Sun sent a gorgeous rainbow for her to travel on.

Take a bear, a snake, a deer, a porcupine, and a mountain lion, they will watch over you.

It was a mile from the hogan to Standing Rock.

The Pack Rat peered down from the ledge.

Their gaze on the treetop where the robin flung notes of joy to the world.

I alone saw the Soft-footed Chief as he walked in beauty past the child of my sister.

WATERLESS

MOUNTAIN

CHAPTER I

THE FRIENDS OF YOUNGER BROTHER

N THE month of Short Corn, when drooping clouds floated white against the blue, and fringed dust rose from the washes, Younger Brother tended the sheep. They were homeward bound, for the sun was in the western sky. Younger Brother was only eight but he felt much older because he was alone with his mother’s sheep. All day he had watched them and cared for the two little lambs who stayed so close to his side. No harm had come to them and soon he would have them safe in the corral under the sheltering cliffs.

Younger Brother was hungry. Already he could smell the coffee and the roasted mutton ribs that his mother was preparing inside the round mud house called the hogan.

He could see his father’s pony tied to the juniper tree. His father was a great silversmith. When he tired of making bracelets and rings, he rode about the desert to look after his cattle.

Younger Brother could remember sitting in the saddle in front of his father. That was a long time ago, before he had a baby sister. Now he was big enough to have a pony of his own but he must herd the sheep so that his mother could have wool to spin and weave, and mutton to cook. He would much rather ride a pony as Elder Brother did.

Elder Brother wore his long hair in a knot because he was a grown man. Uncle had given him his turquoise earrings, which were family heirlooms. Uncle was Mother’s brother and he was a medicine man. He told stories in the winter time while everyone sat around the fire in the middle of the hogan.

Younger Brother liked the winter time with its stories and its pine nuts, but he liked the month of Short Corn too, when the lambs were strong and jumpy, and the baby cottontails hid under the sagebrush. He liked every month and every day, and he liked to get home with his mother’s sheep.

“Yego, hurry!” he called, as he threw a rattling can of pebbles toward the flock.

Mother met him at the corral and helped him put up the bars. Then they entered the hogan for supper.

Baby Sister greeted them with a laugh. Like all other Navaho babies she was tied tightly in her cradle which was just a board. The tie strings which criss-crossed in front were like the lightning. The bow to hold the canopy was like the rainbow and the fringe on the side was like the rain.

Baby’s arms and hands were wrapped inside the blanket and she couldn’t move her body on the board. She could only move her head from side to side, but she was happy and content until she saw Brother eating. She too was hungry and she cried so loudly that Mother untied her and gave her a mutton rib all juicy and sizzly from the fire.

When darkness came everyone lay down on his own sheepskin and fell asleep. That night Younger Brother had a dream. It was about the Yay. Yay is the Navaho word for a god or holy being. Younger Brother dreamed of the first time he saw a Yay. That was in the month of Slender Wind, when his Uncle had given a sing, or healing ceremony, for Mr. Many Goats.

On the eighth day of the ceremony twenty boys and girls were to be initiated. They sat on the ground in a semi-circle, with their backs to the north. All the boys were naked but the girls were dressed in their very best velveteen jackets fastened with silver buttons. Strings of turquoise and coral hung about their necks.

The children had been told to sit quietly with bowed heads and wait for the Yays to come. Some of the girls had their mothers beside them but the boys were alone and trying not to be afraid. Younger Brother heard the cry, “Wu hu, wu hu!”

Looking up he saw the holy one with naked body all dazzling white and with a mask of deerskin over his face. The Yay’s long black hair fell over his painted white shoulders and a fox skin hung from his silver-girt waist.

Younger Brother was told to stand while pollen was sprinkled over his body. After that he was struck with two long yucca leaves. He was not afraid. He did not cry a bit. He was feeling queer. He had never felt like that before. It seemed as if the whole world were whirling light and warmth. He could feel life gliding over him in warm waves.

He laughed without making any noise. He could smell fresh green things growing, though there was nothing but dry sagebrush about him. He could hear the song of the mocking-bird and of Doli the bluebird. He could hear the notes tumbling and pouring over one another, though there was not a bird around. He could see colors shimmering about the white body of the Yay. He even felt as if his feet left the ground and he were lifted up into the air.

In his dream of this initiation, Younger Brother lived his ecstasy over again. He knew that, like the Navaho boy who was given wings, he could fly right up to the sky, and he did.

He played with the Star Children. They were lovely children dressed in brilliant sharp stones of blue and white and black and yellow. They sparkled from their own light and when they laughed, little specks of star-dust shook from their finger tips and toes. They carried bows and arrows. Sometimes they sent a shaft flying into the dark, and people of the earth said, “There is a shooting star.”

Just as Younger Brother dreamed of the shooting star he awoke. Everything in the hogan was still but through the smoke hole in the roof came the sound that star-dust makes when it falls to earth. Younger Brother looking up, whispered, “Big Star, I am your child, for I have heard your song.”

After that night of dreaming, Younger Brother noticed that many more wonderful things happened, even in the daytime when he was alone with the sheep. If a whirlwind came twisting toward him he sat very still and said, “Wind, I am your child, for your trail is marked on the ends of my fingers.”

It was the same with the clouds that he watched. They were living beings to him. He ran races with cloud shadows that purpled the mesas, and laughing he called, “Cloud, I am your child, for you have poured water in the rocks for me.”

He loved the rainbow best of all, for when it came to watch over the month of Short Corn, it stretched its beauty to the month of Tall Corn. Younger Brother, sitting in the shade of the tasseled corn, spoke to the Rainbow People:

“Rainbow, I am your child, for you have brought the rain to the parched earth and the corn is green.”

When the thunder spoke, Younger Brother was silent, for he felt very small then and wished he were home with his mother, her child in her arms.

One day when his mother had finished weaving a rug, she packed it with a sheep pelt on the back of a burro. She lifted Younger Brother up in front of the load and they started down the canyon to visit the trader.

Younger Brother had never been to a trading post. He had never seen a white person in all his eight years. Mother walked, leading the burro. The sun shone on the yellow cliffs and the shadows fell in welcome strips of coolness across the sandy wash.

Younger Brother was happy and excited for he was to see strange sights. Mother would know what to do. Mile after mile they traveled in the sand, sometimes passing little peach orchards on the edge of the wash.

When they came to the prehistoric cliff dwellings high up in the rocks, they hurried by, for the holy people live there and it is not well for the people of the earth to disturb them. Younger Brother was glad every time they were safely past.

The sun was almost overhead and Younger Brother was thirsty. He could see no water about, but he told Mother he must have some. She went to the edge of the cliff and dug a little hole in the sand with her hands. In a few moments it was filled with water that seeped in from below the dry sand. Mother always knew what to do.

It seemed a long time before they reached the trading post, but just as Younger Brother was thinking they never would arrive, they turned a bend in the canyon.

There at the base of a rocky hill stood a group of houses, different from any the boy had ever seen. They were not round like a hogan nor were they made of logs and mud. To Younger Brother they seemed huge and reminded him of the cliff dwellings.

He was frightened. Maybe the white people who lived there were like the holy people of the cliffs. Mother wasn’t afraid. He could tell because she was lifting him to the ground and tying the burro near a Navaho wagon loaded with sacks of wool. It must be all right.

Mother went straight into the store with her blanket and sheep pelt. Younger Brother clung to her skirt. When he dared to look up he saw row after row of canned peaches and tomatoes piled on shelves to the ceiling. Lower down there were rolls of bright calico and velveteen and plush. This must be some kind of magic house to hold so many beautiful things that people liked.

Mother walked through the store and opened another door. There in a very small room sat a very big man. He did not sit on the floor as Navaho men did. His feet only were on the floor and he sat up in the air on a board supported by four sticks. Another wide board on higher sticks stood in front of him, and the Big Man made queer clicking noises on rows of little round white things that he pressed down with his fingers. The fingers worked rapidly and surely, like the feet of the Yays when they dance in a ceremony.

The Big Man did not look up nor say a word. He continued to press the little round white things as if his life depended on them. After a while, out of the object he was punching, he pulled a piece of white paper covered with small black marks.

Looking up he saw Mother. He smiled and held her hand.

She said, “Grandfather,” not that he was old, but because that is a term of respect among Navahos.

Then the Big Man patted Younger Brother on the head and said in Navaho, “Grandchild.”

Younger Brother thought he had never seen so kind a face and he knew right away that the Big Man must be a medicine man. He could feel power shining through the blue eyes, and tingling in the fingers that touched his head.

He thought how comfortable it would be to stay near the Big Man with the kind voice. He hoped Mother would bring him to the trading post every time she had a blanket to sell.

The Big Man had only said “Grandchild” and patted him on the head but Younger Brother knew that, like the stars, the clouds, the rainbow and the dawn, this man was his friend.

CHAPTER II

YELLOW BEAK

HEN Younger Brother and Mother reached home again late in the evening, all the family awaited them. Baby Sister was creeping on the floor and playing with the gray tiger cat. She waved her hands and laughed when she saw Mother. Everyone wanted to see what Mother had brought from the store. Of course there would be sugar and flour and coffee and maybe there would be canned peaches.

Sure enough there were canned peaches and a can of strawberry jam. Mother was surprised to find the jam because she had not traded for it. The Big Man must have put it in for a present. Younger Brother was sure it was meant for him because the Big Man had called him Grandchild.

Every time Younger Brother became acquainted with people they gave him something to remember them by. The Star Children had shaken star-dust to him. The Cloud People had poured water for him. The Earth Mother had given him corn to eat and now the Big Man with the smile had given him strawberry jam. He would keep the colored picture that was on the can. He put it inside his shirt while no one was looking.

Mother saved the jam for breakfast and next morning, which was warm and sunny, everyone sat outside the hogan to eat. The coffee boiling on the campfire added new sweetness to the desert air.

The lambs skipped over the rocks and bees buzzed about the sagebrush. The lone cottonwood tree harbored a host of little birds and one mocking-bird sang as loud as he could, in imitation of all the other bird people. It was a morning when everything sang a song.

Younger Brother strolled toward the corral, still eating his strawberry jam. There was jam on his bread, on his little brown fingers and all around his lips. The bees were attracted to it. They thought it was some new kind of sweet red flower. They settled on the edge of the bread and began to eat their breakfast.

Younger Brother stood still to watch them. He did not brush them away and soon they were crawling on his hands and one even lit on his sweet red lips and ate to his heart’s content. When they were through he said to them:

“The Big Man sent it to us. He is our friend.”

So while the sweet cedar smoke rose to greet the morning sky and while the birds sang and the bees buzzed, Younger Brother let down the bars of the corral and all the sheep ran out, ready to start on the daily hunt for grass.

Mother was boiling water on the campfire for the red dye she had brought from the post. Already she had shrunk her white yarn in the hot water and had wound it round and round the outside of the hogan to dry. Because she shrunk the yarn she spun, the finished rug kept its shape when it was washed. Mother made the best rugs of all the women.

Father was melting Mexican silver dollars in a clay crucible and pouring the molten metal into a mold chiseled out of sandstone. He had greased the mold with mutton tallow before pouring in the molten silver. He was making a bracelet for Younger Brother. It was to have a very blue turquoise set in the middle with butterflies engraved on each side of the stone. Father was a very great silversmith.

Elder Brother had gone rabbit hunting and Younger Brother must be off with the sheep. Every day he had to travel further from home because, little by little, the grass was disappearing before the hungry sheep. The little shepherd went higher up the canyon than he had ever been before.

He reached the place of crooked rocks where the crooked stone people sat around in circles. They sat around a stone fire with stone flames and everything was quiet. Younger Brother knew that some of the huge crooked rocks had once been giants, who went about the country destroying people.

He had heard about the two splendid children of the Sun Bearer, who had come to earth to save the Navahos from the wicked giants. He knew how the Sun Bearer had given weapons of lightning to his sons and how they had hurled thunderbolts at the giants to slay them.

Younger Brother was most respectful to the crooked rocks. He let the sheep graze at their base but he wouldn’t think of climbing on a lone rock himself. He watched the birds fly about them and he wondered if there were any eagle nests resting in the arms of the quiet stone giants.

He knew that the Eagle People lived somewhere in the deep blue, high above the people of the earth. He was respectful to the eagles also because he knew they could look down on him and see everything he did. He was extremely respectful in his thought of the Eagle People, who seemed as mighty as the sun that was shining so ardently on the strange weird forms of the stone giants.

While the sheep lazily grazed in the noontime, Younger Brother rested in the shade of the rocks. He could hear the wind singing in the canyon. The Wind People were always kindly in the summer time. They played with tumbleweeds, rolling them over and over and making them hide in the little hollows at the base of the cliffs. They danced in spirals in the sunshine and sometimes they lifted the red band off of Younger Brother’s head and waved it to the tumbleweeds.

The little boy felt very lazy lying on the ground with his hands behind his head. He felt dreamy and drowsy while the wind murmured in the canyon. He listened to its song and soon he seemed to hear the words:

“Look up, Grandchild, look up, Grandchild.”

He looked up, way, way up to the crest of the strange rocks and there he saw Yellow Beak, the eagle. He had ridden the sun rays from out of the far blue and was resting on top of one of the rocks. He was as still as the rocks themselves. Everything was still. The wind stopped singing, the tumbleweeds lay quiet, and even the sheep were motionless before the majesty of Yellow Beak.

He did not move a feather. He just looked down at Younger Brother with his strong eagle eyes which could look straight at the sun without blinking.

Younger Brother was very still too, looking up, looking up. He felt small and earthbound and respectful, oh, so very respectful. He was not afraid of Yellow Beak, and he was not wishing for Mother as he did when the thunder spoke. He was just looking up and Yellow Beak was looking down, but both of them knew that something was happening.