Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

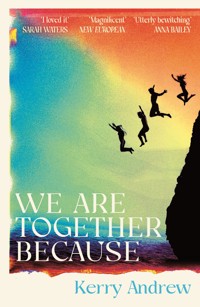

Luke, Connor, Thea and Violet spend their first holiday together alone in their father's house in the south of France. The boys don't really know him, and they don't really know their half-sisters, either. Luke, the most easy going of the four, is keen to bring a new shape to their overlapping, unconventional family; Connor and Thea, born just six months apart but a world of difference between them, are struggling to hide their attraction to each other; Violet, the youngest, is trying to figure some things out about herself, and trying desperately to forget others. Sex in all its multiple forms is on the minds of the siblings during the hot, lethargic summer days spent next to the pool, but the land around them is starting to respond to something inexplicable and eerie. Animals begin to act strangely. There is a buzzing sound that only Connor can hear, and when Violet one night sees a plane light abruptly disappear in the sky, it signals the beginning of something that threatens so much more than their turbulent holiday. With considerable power and unfolding revelation, We Are Together Because starts as a sensual summer drama and very quickly becomes about our own survival, asking us what is truly important in life, and how far we've strayed from our place in a more fluid, vibrant, natural world.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 360

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

WE ARE TOGETHER BECAUSE

Also by Kerry Andrew

SkinSwansong

WE ARE TOGETHER BECAUSE

Kerry Andrew

First published in hardback in Great Britain in 2024 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

This paperback edition first published in Great Britain in 2025 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Kerry Andrew, 2024

The moral right of Kerry Andrew to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

References to the work of Pauline Oliveros have been kindly permitted courtesy of PoPandMoM.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

EBook ISBN: 978 1 80546 019 0

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

In memory of my beloved friend and bandmate, Matt Dibble.

We ought to be grateful to our senses for their subtlety, fullness and force, and we ought to offer them in return the very best of spirit we possess.

FRIEDRICH NIETZSCHE

Deep Listening represents a heightened state of awareness and connects to all that there is.

PAULINE OLIVEROS

By and by comes the great awakening, and then we shall find out that life itself is a great dream.

ZHUANGZI, TRANSLATED BY FUNG-YU LAN

The past is a foreign country: they do things differently there.

L. P. HARTLEY

AT ANY MOMENT DESTRUCTION MAY COME SUDDENLY AND THEN WHAT HAPPENS IS FRESHER.

JOHN CAGE

PART ONE

One

The sun never reached this part of the river.

It was cold, unswimmable. The sheer limestone cliffs narrowed to just a few feet apart, and merged into one on the water’s marbled, flat surface. Elsewhere, the ancient walls were deep with moss and ferns that never lost moisture.

Caves were dug here, places of dark and quiet when there was nowhere else. Red ochre striped by fingers onto white rock. Strange shapes – lines moving outwards from one central point, webbed together. A child, buried with a polished axe and a flint blade.

Hundreds of metres above the gorge, the land was once hard in summer and hard under snow in the winter months. In the hills, past a village that prided itself on almonds and lavender, sat a farmhouse, 153 years old, and built with mountain stone. Home to three generations who spent long days amongst their sixty sheep, and short nights packed too tight into its rooms. Over a century and a half, clusters of houses appeared around it, vineyards and olive groves spreading further. The Great War came, and the family dispersed. The farmhouse began to crumble at the edges, tiles cracking, stairs slanting, before the tourists started to arrive.

Now, along with a third of the houses in this south-eastern corner of France, it was a summer residence. William Low had purchased it nine years ago, regularly leasing it out to friends and work colleagues when not staying there himself, which he did with less frequency than he’d ever intended.

This time, he did something new. He sent his offspring – his lopsided family, slipshod in the middle – ahead, whilst he worked on completing three simultaneous cases and tried not to worry about how they would get on.

William would not see his children again. No one would.

It was late July, and the youngest of his four progeny was currently standing one-legged on the high wall above a slanted slope of young green oak and olive trees and was, not for the first time, thinking about killing herself.

* * *

If she fell now, she would hit her head on a rock and split it open. If she tried to jump, get height on it, she might impale herself on a branch. She could at least break a leg, with enough effort.

Violet swivelled around on the heel and ball of one bare foot, to face the garden and the pool and the house. She could stand on one leg for ages. A very warm breeze lifted up the hairs at the bottom of her neck. Do it, Violet, it whispered. Disgusting fucking bitch. She could just tip back, let herself go, arms outwards.

Violet. In her etymology app, violet was a small wild plant with purplish-blue flowers, c. 1300, from the Old French ‘violete’, from the Latin ‘viol’. The last colour in a rainbow. The name great-grannies had. You couldn’t shorten it, except to ‘Vile’, which some girls whispered not very quietly, or ‘V’, which some boys demonstrated by waggling their tongues through two fingers. Up yours. The victory sign. Vee Vye Vo Vum.

Her sister’s name was two of the most basic words in the English language stuck together, and yet it meant goddess of light, mother of the sun, moon and stars.

Big brother one: light, again. Giver of light. Big brother two: strong and wise and apparently a lover of hounds. She should have that one – dogs were her number-one favourite.

Dad had obviously worked his way down, from normal names that normal people had, to embarrassing ones. LukeConnorTheaViolet. Trust her to be last.

It was fucking annoying.

Violet had been watching trash TV with Dad back home in London – for all his lawyering and history books as heavy as bricks, he was a sucker for people marrying strangers and entrepreneurs making fools of themselves – when he proposed the holiday.

‘What do you think about France with Luke and Connor this year?’ he’d said, putting his hand in the bowl of popcorn.

‘Cool beans!’ Violet had said, before he mentioned that he’d be working in Beijing for at least the first week. She felt like she’d been trapped into it, but was still excited – they’d only ever seen each other the odd time. ‘Parent-free zone. So like Love Island meets Lord of the Flies.’

‘Hmm,’ said Dad. ‘Hopefully neither of those things. If you don’t think you’re old enough, kiddo, just say. You can come with me in the second week.’

‘I’m old enough,’ said Violet. ‘I’m very mature. It’s Thea you’ve got to worry about.’

‘Be nice to your sister,’ Dad said, as he often did, quite interchangeably, to both of them.

Violet tipped her face up, still wobbling precariously on one leg, and squinted through one eye.

No violet here. Blue and then some. You could absolutely one hundred per cent guarantee that the sky was going to be blue, no matter what. Even before climate was followed by crisis, not change. Big, bright, slap-you-round-the-face blue, all of the blues possible if you looked from Dad’s room, which was at the front of the house and which Luke had commandeered until Dad got here. Lake. Sky. Pool.

Cyanotype blue. Her mum had put her on a photography course last summer and now she had a Canon EOS 4000D DSLR camera and a lens for it, and she liked looking at proper old-school cameras in second-hand shops and on eBay. Together, they had gone to this really cool exhibition about early photography, and it had made her look at her phone like it was a piece of Lego. Imagine seeing this stuff for the first time – things appearing on metal plates or paper, as if rising from the depths. They would have freaked out.

William Henry Fox Talbot, Cecilia Glaisher. The first photographers used salts of silver and acid, experimenting until the vase of flowers didn’t turn black, until the silhouettes of ferns became crisp and alive.

Anna Atkins mixed two diluted chemicals together so that they were sensitive to ultraviolet light, brushed them onto card, and left them to dry in the dark. Then she squashed seaweed or algae between two plates of glass onto the paper and exposed it to the sun. The plants came out chalk white on a dreamy blue, like skeletons.

Ultraviolet. Ultra meaning beyond everything, on the far side of. She was ultraviolet, in that she was so unlike her stupid name it was untrue.

She would erase herself, one way or the other. She could forget, be someone different who it hadn’t all happened to. But not different as in dead. Not yet. Fuck you, death-whispering breeze.

She lowered her hovering foot, bent her knees so that she could rest one hand on the blistered white paint of the wall, and jumped down into the back yard.

* * *

Thea was lying on her bed, thinking about sex.

This was not a new activity, to be fair – not in one sense, in that for a long time she had been thinking about what it would feel like, and whether it would hurt, and whether a boy would be disappointed in the size of her breasts or bum or hips, or be distracted by the spot on her chin – but it was a relatively new activity in that now she had finally had sex.

A few times, actually.

She shifted, and the sheet came with her, stuck to the backs of her thighs. The heat was a constant reminder of skin pressing down on her, of being enclosed by arms and legs, the sheer blissful terror and suffocation.

She put her hand between her legs and pushed upwards, just to relieve the pressure, to make it spread throughout her body and not feel concentrated in that one place. Bruised, in a good way.

Metaphysical pessimists in the philosophy of sexuality – St Augustine, Kant, Freud sometimes – believed that acting on the sexual impulse was unbefitting to human dignity, and a threat to one’s very personhood – that either side might get lost in the sex act and become just a thing. Metaphysical sexual optimists – Plato, Freud again, Russell – saw sexuality as just part of human existence, and something to be relished. In your face, Kant.

It was easy. After the first time, anyway. After wondering how she would be able to accommodate anything larger than a super-sized tampon – and even those felt a bit full-on sometimes – it had really been a surprise how smoothly it fitted. She was a natural.

Thea had been behind, really, compared to others. Compared to Jade, who’d whispered in her ear one morning in tutor group, aged fifteen, that she had been – in her words – deliciously fucked. Compared to Mischa, who had decided to give up smoking once she’d started having sex aged fifteen and a half, because one vice was enough, and sex was cheaper. Compared to Harper, who’d started going out with the captain of the football team in their girls’ school earlier this year. She was finally part of the club.

There was a loud splash that was almost definitely Violet bombing into the pool for the fifth time this morning. When her little sister was seven, she would hit the tennis ball on a string in the back garden over and over again until Thea, aged ten and fed up with the incessant thock every afternoon, cut the string.

She didn’t know what Luke had done when he was seven. Or Connor.

She supposed that Dad wanted them to get to know each other more, as if they hadn’t had enough awkward birthdays and Christmas parties. But living together, the two boys and two girls – this was different. She’d have to get used to this sort of thing in another year, sharing rooms in halls wherever she ended up. But at least she wouldn’t be related to any of them.

Two days and already it felt like weeks. Jade and Mischa had gone interrailing in Eastern Europe, something they’d been planning since January. Thea’s mum had said she needed to be eighteen to go and she’d sulked for a week. She would experience their holiday vicariously through her phone, and otherwise use the time here to read all five of her Very Short Introductions as a pre-boost to her A levels, attempt and probably fail to tan, and find a French boy to explore the complexities of Plato’s thoughts on eroticism.

She peeled herself off the bed and went to the window, looking down onto the bleached paving stones and the pool.

Connor was crouched down in shorts and a black T-shirt, wearing those huge headphones, holding the recording thing in his hand. Motionless. She imagined pushing his shoulder so that he toppled over into the bushes.

Thea could hear him through the wall at three in the morning, things bumping, making his crunchy-sounding, completely impenetrable music. Not even really music, as far as she could make out. She wasn’t entirely sure that he’d had sex.

Just one of the many ways in which she was better than him.

* * *

It was definitely there. Connor wasn’t imagining it.

In the 1940s, the composer John Cage went looking for silence. He entered an anechoic chamber at Harvard University, designed to completely block out the sounds of the outside world. To swallow sound whole. Yet when he stood there, there were two sounds, one very high and one very low. When he complained to the sound engineer that the chamber was not up to scratch, the engineer explained rather patiently that the high one was his nervous system and the lower one was his blood circulating.

In his bedroom, Connor took off the headphones, breath shallow, not swallowing. He could hear the sparrows outside on the telephone wires. A dog, with a hoarse and angry bark. Luke, downstairs in the kitchen. The cockerel’s toy-trumpet fanfare went off half a mile away, as it did throughout the day. Still, he couldn’t detect it. Not out there.

He put his headphones back on and listened again to the recording he’d made outside. He had been trying to get something of the little sucking sound of the water in the far corner of the pool, and had got distracted by the scrape of dry leaves in the faded green bush next to it. But listening back to it on his laptop, he’d found something else he hadn’t noticed before.

There, again. A high whine, just at the edge of hearing. Almost electronic. What was that?

Connor’s left ear was very good. Highly tuned, toned as a swimmer’s limbs. The other one barely worked, had never worked, due to bone forming to completely block the ear canal while he was in the womb. Atresia. An ear only hearing itself. At least with the right-hand level whacked up on studio headphones, he could get the vibrations through his skull. A semblance of stereo. He wondered what John Cage would have done with only one ear. Made some cool pieces, probably.

He stared at the laptop screen, running his fingers lightly over the keyboard. Half-deaf. Another way in which he was a half.

Little dark, sporadic peaks spiked on the track in front of him. His audio recorder had picked up footsteps, a flat tackiness of skin on concrete that got louder, stopped, started again and faded. He’d known Thea had been there, and he hadn’t turned round.

She was walking in a different way. Like skinny models did, their shoulders slung back as if dislocated, arms flopping. With the same constant, dreamy smirk.

The two of them, Connor and Thea, knotted in the middle, too close in age. If anyone ever asked, he either said he had two sisters – no half – or didn’t mention them at all. It wasn’t like they lived together, or were even in the same city.

They overlapped. It was like a confusing exam question for primary school kids: A brother is six months older than his sister. Explain.

Answer: Their father was a cheating bastard who had got his girlfriend pregnant with a second son and then got another woman pregnant before the son was even born.

The door smashed open, bouncing back off the bookshelf, and Violet strolled in. Denim shorts and a T-shirt saying TEENAGE APOCALYPSE, a dirty feather tucked behind her ear. Three tight bands had been drawn around her wrist with three different-coloured pens. She did a quick circuit of the room, her fingers on the windowsill, his desk. ‘What you doing, brobro?’

Connor slid a headphone behind his ear and showed her what he’d been working on – chopping up his field recordings, layering them to make textures, beats even.

‘Gimme,’ she said, her hand out.

He clicked on a recording he’d made yesterday and stared at the screen as the bar moved along. He wasn’t sure what he’d do with them yet. Keep recording, editing and combining, playing around with modulations and filters, until something came out.

‘Sick,’ she said, giving him back his headphones. He was fairly sure she wasn’t much interested, but it was nice that she pretended. ‘I’m going to be called Hawk from now on. Here, anyway.’

‘OK.’

She pointed two fingers, shot him. A book fell off the shelf as the door slammed behind her.

It was always easier to talk to Violet, because she was four years younger than him. Because she wasn’t his weird half-twin.

Because she wasn’t beautiful, like Thea.

Connor moved the headphone back onto his deaf ear. He sat very still and listened again to today’s recording, to the long, unpulsing drone.

* * *

‘Oh, God. Yes.’ Luke sucked on his fingers. ‘Jesus.’

The hottest part of the day. He hadn’t got his body into siesta mode yet but hopefully he would soon. Instead, he was in the kitchen, with the blinds lowered.

He pressed his tongue to the roof of his mouth. Closed his eyes and swore. Blasphemed.

Degree over, it was absolutely fine to have to be lord of the manor here (manoir? Luke’s French was sketchy, if enthusiastically delivered) for a while, and to have some distance from a certain man’s suburban house where he’d ended up one too many times.

He opened his eyes and looked at the spread on the counter in front of him. The high-intensity tomatoes. The goat’s cheese, thick and cummy. The tang of the wild garlic.

He was a person of different layers. He was robust, tall, a rower’s thighs, and could run up and down a football pitch for ninety-plus minutes without stopping. A proper Manc lad, but also one with a penchant for wearing glitter gel eyeshadow on a Saturday night as he chugged his cheap lager. And he was obsessed with the intricacies of flavour, especially the ones that the Mediterranean sun coaxed out. Which is why he was grateful that his mum had allowed his father to be in touch after a long hiatus aged three to fifteen, and that his father was actually a good guy, if constantly awkward when looking at Connor, and that his father had a successful job and could buy a place in the South of France which had a decent kitchen.

He was given the job aged sixteen of cooking on Thursday nights, when his mum was back late from her community choir rehearsal. Ham and eggs turned into spag bol turned into salmon fillet with tarragon butter and samphire, until Connor became a vegan, and then Luke liked the challenge of making meals just as good. You could run a restaurant, his dad had said, the last time they were here, and Luke had flushed with pride.

He was a sucker for compliments. For anything, really. He liked that their dad made an effort. Will was an Arsenal fan, but happily took him to the City game as one of their first outings together, Luke thrumming with excitement at sitting next to his actual father. Connor, on the other side, had a stiffness that grew over the years into a stubborn refusal to share any interests with Will. Part of Luke admired his brother for it, but he always wanted to reach out, welcome in, accept, forgive. Love was love, and it was messy and complicated.

He put in his headphones. He and his mates shared a playlist called dancebabydance and a few new tunes had been put on. This one was too bland for him, with the essence of Canal Street on a Saturday night, full of cishet tourist trash. He preferred old-school Chicago house and classic disco, but hey – he was easy. He shook his hips a little as he finely diced the garlic leaf, and pictured Jamie watching him from behind, telling him what he’d do to him with the courgette in his dour Midlands accent.

No. Not good to think about Jamie. Better to concentrate fully on this garlic leaf, foraged from the shaded woodland a few miles away, its delicately rubbery texture, the full-on scent. No way of that being used aggressively.

His phone buzzed. Where are you? Why aren’t you answering?

‘All right,’ said Connor, walking into the kitchen with four dirty cups hooked in his fingers and those massive headphones round his neck, opening the fridge door.

‘Y’all right,’ said Luke, putting his phone back in his pocket. ‘Chuck us that mint?’

His brother didn’t always say very much, but he was a good soul, underneath the furrowed brow and the permanently attached headphones. If slovenly.

‘What you making?’

‘Dunno yet.’ He took the bunch from his brother. ‘Cheers. Want some? It’ll be ready at eight.’

‘Yeah, maybe,’ said Connor, taking a carton of juice out of the fridge and leaving the kitchen as he tipped it to his mouth, off to do his own thing once more.

Luke wouldn’t have minded a bit more coherence, siblings-wise. When his dad had called about the holiday, Luke had felt cheered, responsible. In truth, he’d been vaguely committed to a Greek-island-hopping booze, beaches and boys trip with his mates, but that could wait. He’d been deemed fit to lead the party, and daydreamed of what they’d all do together, his expanded family. But then he was a team player. Mad for competitive sports, both playing them and teaching others in the future. A PGCE in PE awaited.

The other three seemed more like individual sportspeople. Violet: maybe ski jump, showy, becoming a cult figure with massive goggles. Thea: something slinky, because that was clearly her vibe at the moment. Ice-skating, so she could wear some tiny outfit. Connor: a featherweight boxer, hurling himself methodically at the punchbag, letting out all his pent-up energy.

Fuck it, though. He would make it happen. The four of them would become a family. A proper one.

Up in the corner of the kitchen by the hairline crack in the older wall, a long-bodied cellar spider rests in a tangle of thread. House spiders are diminished by its presence. For a moment, it vibrates, as it does when a predator is near. A shimmer of spider, becoming a blur to disguise itself.

Then it continues its web-making, the pattern a little more ordered, more precisely angled than it has ever been before.

Two

Leaves. Leaf-bits. A wasp. Two daddy-long-legs. Why were they dads? Mums could have long legs. Not all females of the species were short-arses, like her. Violet Little Legs.

Violet was cleaning the pool. It was her routine every morning when she was here. Up, brush teeth, eat a bowl of dry chocolate French cereal that she called Le Coco Pops, walk a bit on the walls and think about killing herself – although that bit was new – and then skim the surface of the water until it was clear of clutter.

She imagined the pool net pole as a spear, bent down and formed a defensive shield wall with her imaginary fellow warriors. She probably had Viking blood, after all – her mormor and morfar, her mum’s parents, were Danish, though they had lived in the UK since they were young. You were supposed to say ‘Norse’, but Violet liked ‘Viking’, even if it did officially mean raiding and plundering. Her mum had been doing the family tree with a cousin for years, and would sit with a glass of wine poring over old documents on her tablet, doing that sing-song hum she did when something was interesting. Hopefully one day she’d trace back far enough to give Violet her berserker badge. The bear-coat wearer. Oh, you are definitely a Viking, her mum would say, a hand on Violet’s head. A shieldmaiden. Anyone would be terrified of you coming the other way. Violet had grinned with satisfaction, though Thea had snorted. Thea would definitely have been a Norse-only person, sitting at home weaving on her loom and complaining that no one had noticed her new, very ninth-century hairstyle.

Violet twisted the pole back round, scooped into the water and lifted again. Sometimes, she imagined that it was a wide fishing net and that she was collecting up shoals of brown flatfish, sea cucumbers, lion’s mane jellyfish, starfish, conger eels, all her thoughts, everything flapping in the fine mesh, all at her mercy. She imagined feeding them to Artoo, who would probably sniff at them and run away.

She’d video-called her mum this morning, and spent a good five minutes talking to Artoo. At home, she did everything with him. He was a cross between a Border collie and something smaller, black and tan, with the biggest, stupidest smile, tongue lolling out as if trying to escape. They’d got him from a rescue place five years ago, and he was her partner in crime. Dogs were nicer than most people. She had built up a language that was part human, part dog. She was training him to do an increasingly badass assault course constructed in the garden at home, and dreamed of winning that competition at Crufts – except that he wasn’t a pure-breed and wouldn’t get in. Secretly, she also tried to cajole him into doing the nerdy owner-and-dog dancing that everyone on social media laughed at, but even Artoo refused that, no matter how many treats she gave him. Thea used to roll around with him, too, but these days she absently pushed him away or told him his breath smelt, as if he could do anything about it.

Violet turned and swept the net again, catching a corner of Thea’s lilo.

‘Careful,’ her sister said as the lilo turned her slowly, not looking up from her book, which was called An Introduction to Consciousness. Hi, Consciousness, nice to meet you, how’s it going? She was wearing her bright-red bikini with the ties at her hips, her shoulders creamy with the suntan lotion that had been tossed in the grass, lidless and dribbling. Apart from the hair on her head, you couldn’t see any hair on her anywhere.

Violet walked the net around the pool again. ‘What’re you reading about?’

‘Transcendental idealism and the thing-in-itself.’

‘Say what?’

‘Immanuel Kant. We can’t fully know a thing, because our senses don’t have the capacity to understand it in its entirety.’

‘Right,’ said Violet. ‘So I don’t understand this tree because it’s got some mystery ju-ju to it that I can’t see?’

‘Or sense in any human way. Yep.’

‘So trees are magic.’

‘I didn’t say magic.’

‘You didn’t not say magic.’

‘Double negative.’

‘Which is exactly how I feel about you.’

Violet swept the net through the water, gathering up five specks that were either vegetation or insects, and let the mesh billow, a wide basking shark mouth. She aimed straight for Thea, collecting the bottom end of her lilo, beginning to eat up her feet.

Thea jerked a leg suddenly, twisted and slid off with a loud splash, the lilo tipping her before gently righting itself. All of her went under the water apart from her book, held upwards with a straight arm. Her head came up. ‘Fuck’s sake. Violet.’

‘Whoops.’

Her sister trod water, one-armed. ‘You’re a certified bitch.’

‘She who smelt it dealt it.’

They used to get on better. They would play word-based board games – sometimes with Dad, who was a total games nerd, but mostly just the two of them. Until Thea started putting down words like quixotry and chutzpah and constantly losing was no fun. By the time Violet had discovered the etymology app – and learnt the word etymology – Thea didn’t want to play any more. Three years was a big age gap once you were a teenager.

Thea pulled herself up to the silver plastic rail at the side. ‘Just leave me alone, all right?’

‘OK. I’ll leave you and –’ she squinted at Thea’s book cover – ‘Immanuel Kunt to be besties.’ Violet pulled the pole clear and rested it on her shoulders, arms draped over it. ‘And I’m not being called that name any more.’

‘Whatever.’ Thea put her book down on the grass and put the flats of her hands over her hair, ironing out the water.

‘Luke said we’re going in half an hour.’

Thea squeezed the ends of her hair and rolled her eyes. ‘Fine.’

* * *

There couldn’t have been much rain so far this year, Thea thought. The fields and the vineyard and olive grove were all bleached of their colour, the ground arid. Her dad had said something about the lavender being underdeveloped, giving less of the fragrant oil that was sold everywhere around here. Some kind of insect contaminating the sap.

‘Je t’aime, mon petit cochon d’Inde,’ Luke was singing, loudly and quite badly, to the crap French pop on the radio. He was the only one old enough to drive the tiny hire car. Next to him, Violet had her filthy bare heels shoved up on the dashboard, her hand out of the open window, laughing. Connor was facing his own back window, turned resolutely away from Thea, not bothering to brush away the brown curls flopping in front of his face. The rest of his hair was short, but he obviously grew them to block the world out. Or her, at least.

‘Le grand bateau est mort,’ Luke sang, drawing out the last word. ‘Parce que le bateau c’est le champignon fabuleux.’

‘Your phone keeps buzzing,’ said Violet, between sniggers. ‘D’you want me to check it?’

‘Non, merci,’ said Luke. ‘Hey, do us a favour.’ He seemed to be speaking to all of them now, and his voice had lost its sheen. ‘Don’t tag me on any photos while we’re out here. I want to go a bit off-grid.’

‘Roger that,’ said Violet.

‘Sure,’ said Thea.

‘Yup,’ said Connor.

‘Ta.’ Luke began to sing to the radio again. ‘Je suis un pomme de terre et tu es mal.’

Violet’s laugh was like an owl, hooting. ‘You are so fucking funny, Luke.’ She was being ridiculous on this holiday. I would really rather you didn’t swear like a sailor, their mum would say. It’s from a Norse word, Violet would say back. Fukka. I’m respecting my roots.

It was easier for them. The outer siblings. Thea and Connor were the core, two sides of a coin. She remembered standing in the doorway of her living room aged twelve, being introduced to two boys who were apparently her brothers. Connor, also aged twelve, looking like her and also not like her at all, had stared over, holding onto his elbows, mute.

Violet – or Hawk, or Tiger, or Ace, or whatever she decided to call herself next – passed back Polo mints, her own one stuck between her teeth. Connor took his without a word. There were a couple of ratty-looking friendship bands and a wooden-beaded bracelet on his wrist, and Thea felt irritated by his attempt at edginess.

He blinked a lot. Just like Dad did when he was thinking. Dad sang loudly in the car, as Luke was doing now. And in the shower, just as she’d heard Luke do this morning.

She’d always known about her brothers, in a not-quitetangible way. She’d heard her parents talking about it once, in low voices, when she was six or so. Them. They. But she hadn’t really understood. They weren’t there in the house, after all. It came into focus only when, aged eleven, she was sat down along with Violet and informed that they had two half-brothers who lived in Manchester.

It was like being told you were adopted. Your whole life-view tilting in an instant. She was the oldest, and then she wasn’t. She spent a long time, in those uncomfortable early meetings, trying to work out whether they looked more like Dad than she or Violet. Couldn’t help still doing it. A competition that she had no control over.

But she could still control some things. She felt this whole holiday to be a test of her maturity, and it was one she was going to breeze through.

As they took the crest of the road, there was the usual stomach-lurch and the half-second of weightlessness, before they began to descend and the familiar turquoise corner appeared down below.

‘Le lac,’ said Violet, taking her feet off the dashboard. ‘Violà le lac, bitches.’

‘Last one in there has to cook tonight,’ said Luke, briefly swivelling round to the back, grinning. At the same time, a van came haring round the corner, straddling the central road markings, alarmingly close.

‘Luke,’ said Thea, a flash of panic in her chest, as they swerved.

* * *

‘Jump!’

‘Shut up.’

‘Three, two, one, go! Go! Oh, come on, sis.’

‘I can’t.’

‘You deffo can. I know you can. Show me your cahones!’

Violet was in the water, having just done a spiralling leap off their jumping rock, four metres high. She didn’t seem to have any fear. Connor had come downstairs yesterday afternoon, bleary-eyed, to find her falling backwards into the swimming pool, arms outstretched and almost perfectly straight. She came out quite cheerfully with red-smacked legs, and did it again.

Thea was standing at the top of the rock, having carefully negotiated her climb at a third of the speed of Violet’s enthusiastic scramble. She’d obviously been trying to move as gracefully as possible, the way some girls did, as if they were being constantly observed.

They’d parked in a lay-by and come down to the spot that he and Luke knew but somehow the girls didn’t, skidding down a trail half-hidden in the trees to a narrow inlet where the cliffs were ten metres high in places. You could still hear the traffic up on the lake road, but otherwise it was just the snap and slop of the water and three members of the fractured Sheridan–Low family shouting at each other, voices bouncing off the flat surfaces. Connor was sitting opposite on the long rock shelf currently scattered with towels, food and a snorkel, reading Silence by John Cage and pretending not to watch.

The lake was lower than last time. Easy to measure against the jumping rock, which had a couple more feet exposed, a strip of dark grey where the water had been.

Violet was whistling and shouting chicken. Thea shook her head, oblivious to Luke climbing up the rock behind her, his finger in front of his lips. Her arms were crossed in front of her, shoulders hunched, and she was in a different bikini, turquoise with an overhanging frill around the top.

Suddenly there, Luke grabbed her hand and jumped with her, Thea’s screech ripping into the air as their bodies plummeted. A short explosion of a splash followed by silence, apart from Violet laughing, and another unleashed yell as Thea came up and swam over to push Luke in the shoulder. He just ducked under, spitting out an arc of water when he resurfaced, followed by a laugh in the same shape.

Luke could do that. Just take her hand and jump with her. He didn’t care. Connor was envious of how easy everything seemed to his brother, who made friends wherever he went. Not really close ones, as far as he could tell, but plenty of them. My son, the social butterfly, their mum had said once, and Luke had given a bow.

Thea was swimming towards Connor now and he resolutely looked at his book, trying to ignore the fact that he hadn’t turned his page in about ten minutes, and listening to her small gasps grow louder.

‘Aren’t you jumping?’ she said, pulling herself onto the rock.

‘I will,’ he said, not looking up.

‘Oh, my God,’ she said, seemingly to herself, and lay back on a towel, closing her eyes and putting an arm over her head to shield herself from the sun. Water dripped from her elbow.

Connor stared again at his page. Turned it, even though he hadn’t read the last two paragraphs. It was supposed to be fine, looking at a family member with hardly any clothes on, because you’d grown up with them, shared bedrooms and baths. It wasn’t supposed to be like this.

His mum called him her Irish rose. His best mate Kaia said, with a wink, that he could audition for Let The Right One In or Near Dark. He caught a bit of colour if he was lucky in the summer, and then it promptly disappeared after two weeks back in Manchester.

Thea was pale, too, in a different way. Her long hair was a neutral shade, not quite brown or blonde, though almost as dark as his now that it was wet. But her eyebrows were paler, giving her a slightly non-human look. Pale, heavy eyelids. She had two pale scars on the side of one thigh as if a big cat had scratched her, a childhood injury he’d never asked about.

‘What’re you reading?’ She turned her head and opened her eyes. Her irises were the same colour as the lake. Not pale.

He showed her the cover and she took it from him, reading the blurb on the back.

‘Hardcore.’ Pretending to have less of a brain than she did. Another sometime-girl-thing that Connor didn’t understand.

He wished Kaia were here. He felt himself with her.

‘Is he a poet?’

‘Sort of. Musician. Composer.’

Thea flipped the book over and squinted up at it, before reading out one of Cage’s nonsensical sections about breakfast and woodpeckers and Kansas. She lowered the book enough to give Connor a wry, almost schoolteacher-y look.

Connor went to take it back. ‘Yeah, well, it’s not all like that.’ Though, in a way, it was all like that.

She held fast. ‘Not finished.’ She swatted at a fly, a gesture that could easily have been aimed at him, too.

The book blocked her face and he looked down at the shadow it made on the frilled bikini top. She made that sound she often did, a little hum as if she was responding to a very quiet question, and shifted slightly on her towel, lifting up and straightening it underneath her hips. Her stomach was moist. Water ran down her inner thigh in pearled rivulets.

A low, tugging pain in his stomach. He stood up, suddenly, and dived into the lake.

The lake had once been an inhabited valley, before it was evacuated and flooded in the 1970s to make the largest artificial reservoir in Europe. Its vast concrete dam sat at the end nearest their house, providing much of the region with its water. They had once looked at the little museum, brown and beige photos of the drowned village – streets and bars and a church. Connor liked to imagine its bell swinging, a misty underwater clang, like Debussy’s ‘La Cathédrale Engloutie’.

He listened for it now as he swam, keeping his head down, the lake deep enough not to be able to see the bottom. The underwater crackle, almost like static, and his breath. He liked to swim, propelling his body, the rhythm of it, losing himself.

Keep swimming. See only milky jade-blue. Not her thigh.

By the time he stopped to rest, he couldn’t see them. He was surrounded by long stretches of water and modest slopes with chalk-yellow sand at their base. The far mountains soft-focus in the heat. He spun slowly, moving his limbs just enough to keep him afloat. The water is thick with monsters ready to devour them, wrote John Cage in one of his lectures, something to do with self-preservation and life and death. Not for Connor. The monsters were absolutely in his head.

The drowned village was much further along the lake than this, he was sure. He got a strange sense of vertigo, then took a breath and swam downwards anyway.

The water grew colder immediately, pressure stacking up behind his ears. Eyes open, he saw the light-blue surface thicken, and looked for buildings that he knew weren’t there. Roofs. A church spire. Instead, he thought he heard something, amongst the intermittent crackle.

A high, constant whine. The same as on his recordings.

When he neared the shore again, he could see the three of them standing in a line, watching him. He kept his head underwater as much as he could, and finally pulled himself up, shaking out his short curls. He supposed he had been gone quite a while.

‘Jesus Christ,’ Thea said, holding onto her elbows.

‘Swear down,’ said Luke. ‘That was a bit scary. Even for you.’

‘Connor,’ said Violet. ‘That was epic.’

* * *

‘Why do we have to eat at the table?’ Luke’s younger sister was not so much at the patio table as on it, leaning her entire torso over to reach for the bread that he’d just taken out of the oven. The sun was setting, a peach blush spread across the horizon.

‘Because we’re in France,’ said Thea, liberally pouring herself red wine. She seemed in her element here, touching things for longer than necessary and experimenting with various reclining positions in her array of bikinis. It wasn’t that long ago that Luke remembered her with train tracks on her teeth, lurking in corners whilst glaring at everyone.

‘Just because their olives are fatter and they eat more garlic doesn’t make them better than us.’

‘Yes, it does,’ said Thea. ‘We suck, remember?’

‘Because we’ve been here three days and we haven’t eaten together once,’ said Luke, sitting down as Connor came in with a pint glass of orange juice. ‘I thought we’d, you know, do a family thing.’

Everyone seemed to stiffen for a moment, concentrating on reaching for something, each sound a little louder. Perhaps that word would always be banned, Luke thought. They were family, and at the same time, they weren’t – two sides stuck together with Sellotape.

Right now, one side continued doing what they did best.

‘Are you seriously saying that –’ Violet grabbed the nearest radish – ‘this only exists in my head? I can smell it. Feel it. Taste it.’ She bit into it with a noisy crunch.

‘So you’re a naïve realist,’ said Thea. ‘Not a radical idealist.’