19,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Nick Hern Books

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

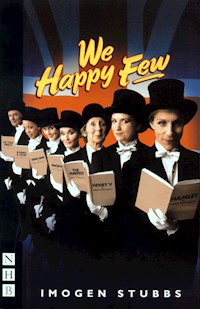

A comedy drama about an all-female theatre company touring Britain during the darkest days of World War Two, written by the well-known actress and premiered in the West End. While the men are fighting Hitler and the bombs are falling on London, a 'girls only' theatre company sets out in a battered 1920s Rolls-Royce to bring Shakespeare to a culture-starved Britain. Imogen Stubbs' play We Happy Few was inspired by the real-life Osiris Players, whose travelling productions during the War inspired many to take up the profession - Judi Dench to name but one. We Happy Few was premiered at the Gielgud Theatre in the West End in June 2004 in a production directed by Trevor Nunn and starring Juliet Stevenson and Patsy Palmer. An earlier version of the play was performed in 2003 at Malvern Theatres.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

Imogen Stubbs

WE HAPPY FEW

NICK HERN BOOKS

London

www.nickhernbooks.co.uk

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Introduction and Acknowledgements

In Search of the Osiris Players

Original Production

Characters

Act One

Act Two

Production Note

About the Author

Copyright and Performing Rights Information

For my mother Heather who passionately believed one should be brave enough to make a fool of oneself

Introduction

by Imogen Stubbs

Several years ago, my eye was caught by a photo in a newspaper of a group of women loading hampers into a Silver Ghost Rolls-Royce. A brief article explained that these seven women were the Osiris Players – a troupe of semi-strolling players led by a Miss Nancy Hewins who travelled across Britain taking theatre to people throughout the country who otherwise had no access to the arts at all. The photo was dated to the 1940s and although the Osiris company lasted for more than thirty years, the article focused on the war years. Between 1939 and 1945, these seven women had travelled tens of thousands of miles giving 1500 performances of a repertoire of over thirty-five plays. They travelled in various motor cars and when petrol was no longer available for private vehicles, by pioneer wagon and horse – and even by canoe. I thought their story would no doubt be snapped up as a wonderful idea for a road movie and forgot all about it.

And then I found myself in the Theatre Museum. My grandmother, Esther McCracken, was a well-known playwright during the 40s and 50s, having written two very popular comedies (Quiet Weekend and Quiet Wedding) and I was giving all the manuscripts I had inherited into the care of the Museum. While I was there, I remembered the Osiris Players and asked if, by any chance, the Museum had any record of them; they came back with five boxes of beautifully preserved archive. There were appointment books, programmes, photos, reviews, lighting plans – everything intact. And at the bottom was a never-published autobiography of the indomitable force behind the whole enterprise – Miss Nancy Hewins.

I found the experience of sifting through all this lovingly preserved information thrilling, funny and extremely moving. So I decided to write a play inspired by the Osiris story. I hasten to repeat ‘inspired’. My play is a fiction; it is not in any way a documentary drama about ‘Osiris’ since many different women were involved over the years and their real stories were not to be reconciled with two or three hours’ traffic of the stage. However, my impression was that Nancy – like Lilian Baylis – was a great pioneer in terms of theatre in education, and the notion of aspirational culture. It seems that from unpromising and often farcical beginnings, she developed a company that through ‘blood, toil, tears and sweat’ became a force to be reckoned with.

Like Blake, she thought of herself as an ‘Awakener’ – someone determined to stir people’s faith in humanity in a time dominated by man’s inhumanity to man.

Her chief weapons were a dogged determination, a courageous heart and, above all, Shakespeare. Her passion, and the passion she instilled in those around her, had a tremendous effect on thousands of young people.

Clearly, the themes of gender – women finding the resource to take over in a world suddenly vacated by men – and communality – the diversity that both separates and bonds a group of artists – were of immediate dramatic interest. But I suppose I respond to a nameless yearning for a lost age as well. Being in my forties, I feel myself suspended between two worlds: an ‘old world’ of telegrams, threepenny bits and Green Shield stamps and a ‘new world’ of computers and materialism. When I grew up, most people had lost fathers or grandfathers, uncles or cousins, in one or other of the Wars – and so my generation felt a direct, rather sombre responsibility to them for that sacrifice. But a sense of history seems at present to feel superfluous to many people, or even an encumbrance – as a teenager said to me recently, ‘I hate history, it’s so not now.’ Our age seems to be sloughing off the burden of history, moving forward armed with incredible technology, but with an alarming lack of humility or identity. And as for the generation of my parents; those aliens from a bygone era of cottage hospitals and sock-darning and hymn-singing in Assembly … of the days before the Union Jack was hijacked by the National Front or the makers of underpants for tourists, they seem to me in my cynical mood to have been consigned to a box labelled ‘not relevant’.

I don’t think we are the ‘new race of philistines’ that some fear, but we do live in a time when to be serious about a non-profit-making venture is looked on as madness – and our consumer society would have us believe that the Arts and spirituality have less to communicate than a mobile phone.

Nancy Hewins looked on the Arts as both our history and our heritage, and perhaps our horoscope too. She believed that through the power of storytelling, you could change society by touching people individually, harnessing the power of collective imagination. She believed that the point of life is ‘connecting’ – that the challenge of being a human being is about being ‘we’ not just ‘me’. And that is also our gift.

She was lucky enough to witness the arrival in 1945 of the great reforming government of the last century – Attlee and Bevan. She was there for the creation of the most enlightened Welfare state, the National Health, the Arts Council, and the expansion of the BBC committed to the three Es.

Thanks to women, like Nancy, and not a few brave men too, I’d like to think I’m lucky to be here – a modern British woman. And what does that phrase really mean? I’m not sure; but I hope it means I have a beating heart and that I should try to carry on the same fight – for as Nancy, Euripides and my mother all had the habit of saying, ‘Civilisation is not a gift of the Gods – it must be won anew by each generation.’

Acknowledgements

My great thanks to Nic Lloyd and Malvern Theatres, the Elmley Foundation, Carl Proctor, Hugh Wooldridge, Bill Kenwright, Thelma Holt and all the other astonishingly generous people who have helped launch the Artemis Players – but above all to Trevor Nunn and Serena Gordon, who have been the wind and the sails.

Special thanks also to David Threlfall, Stephen Rayne, Matthew Lloyd and Sandi Toksvig for their much valued input early on.

In Search of the Osiris Players

by Fred Moroni and Louise Russell

Those who go in search of the Osiris Players will no doubt find themselves in an imposing building somewhere west of Kensington. There they will find Blythe House, once the London Post Office Savings Bank but now the home of the London Theatre Museum Archive. And there, alongside somewhat grander relics – early editions of Shakespeare perhaps, or costumes worn by the great actors of the past – they will find five dusty brown boxes which house almost all that remains of the Osiris Repertory Company and whose contents paint a broad, if somewhat incomplete tapestry of that company throughout its thirty-odd years. There are posters and playbills; receipts and account books; tour schedules and lighting plots; letters and newspaper cuttings; but what characterises this collection above all is the powerful presence of the company’s founder, Nancy Hewins, whose influence is found on nearly every scrap of paper therein.

Born in Grosvenor Square in 1902, the last of three children and the only girl, Nancy Hewins enjoyed a privileged childhood. Her father, William Hewins was an economist and a friend of the pioneering socialists Sidney and Beatrice Webb. They appointed him to be the first director of the London School of Economics. Beatrice Webb, who stood as godmother to Nancy, described Hewins as ‘original minded and full of energy and faith’, although she also noted his fanaticism, as did another family friend: George Bernard Shaw. Hewins was later elected to Parliament as the MP for Hereford and, at the height of his career, became the Under Secretary of State for the colonies.

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!