Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

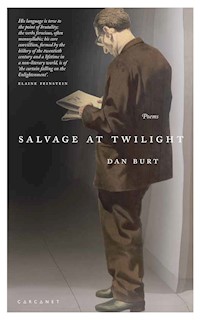

- Herausgeber: Carcanet Poetry

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

We Look Like This anatomizes how history, violence, power, lust and mortality at work on us. Burt's formal, muscular language evokes war, want, cruelty and hope, and a childhood among tough Jews' in Philadelphia, dominated by his father Joe, son of Ukrainian immigrants, butcher, boxer and, last, coastal fisherman.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 128

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

DAN BURT

We Look Like This

for J.R. and A.C.

Acknowledgements

Some of the poems in this book were previously published in The Eagle, The Courtauld News, Financial Times, The Grove, The New Statesman, Newsletter of the Institute for Advanced Study, PN Review, Poetry Review, TLS and New Poetries V (Carcanet, 2011).

A Note on the Text

The poems in this book use a mixture of British and American English, while the prose memoir uses wholly American English. This is not inadvertence, but a deliberate decision on the author’s part.

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Acknowledgements

I

Who He Was 1–5

Death Mask

Slowly Sounds the Bell

II

Certain Windows

III

Circumcision

Indices

Inquisition

Rosebud

Ishmael

IV

Accounting

Death Rattle

Blind Date

Texaco Saturday Afternoon Opera

Cabaletta

All the Dark Years

For John Crook

Homage for a Waterman

Facsimile Folio

John Winthrop’s Ghost

V

Pastiche

Poetry Reading

After Lunch

Little Black Dress

Kept

Pas de Deux

Winter Mornings

Yester-year

Revenant

Sie Kommt

The Faithful

End of the Affair

VI

Decorating the Nursery

Wine Circle

Dodge-Ball

Blue Rinse Matrons

Momentum

Three Sonnets on the Coup de Grâce

Uphill to the Right

Manqué

VII

Compounds

Modern Painters

A Brewing Tale

The Lesson

Rigoletto

Summa

Motes

Un Coup de Dés

Identity

Beside a Cove

The Institute

Trade

Notes

About the Author

Also by Dan Burt from Carcanet Press

Copyright

I

Who He Was

(Joe Burt 1915–1995)

1

He catapulted from his armchair,

airborne for an instant, primed to smash

the fledgling power who dared challenge

his rule. That runty five-year-old who would

not stop his catch to fetch a pack of Luckys

crossed some unmarked border, threatened

the kingdom’s order and loosed the dogs of war.

No chance to repent, no strap, no bruises

on my face, my mother’s screaming just static

behind the pounding taking place; rage spent,

sortie ended, he thumped down the stairs

to his crushed velvet base, pending new

provocations to launch him into space.

Worse followed till my biceps hardened,

but that first strike left most scars: with strangers

six decades on klaxons ahwooga,

the clogged heart hammers, I weigh my chance.

2

A scion of the tents of Abraham

born during World War I, he policed

a patriarch’s long list of rights: no one

but he sat in the fat feather armchair

confronting the TV, or at our table’s

head, read the paper before he did or

said Let’s go somewhere else when we ate out;

if he fell sick the house fell silent, roared

and we all quaked.

I was chattel as well

as son and he sold my youth for luxuries:

an extra day a week to fish, lunch time

shags with his cashier, a kapo’s trades.

My anger, like an old Marxist’s, leached

away as parenthood, mistakes and time

taught Moloch is a constant. Attic myth,

Old Testament, bulge with sacrificial

tales, the Crucifixion one more offering

to Baal; families recapitulate

phylogeny, it’s what fathers do.

3

the golden land in the ’thirties

Morning he threads russet gorges

of two-story brick row houses –

short pants, pals, eighth grade

shut behind him – and evening

draggles home past trolleys full

of profiles who paid the nickel

he can’t afford to ride.

No one

waits dinner: his mother leaves cold

soup in the kitchen (on Fridays

chicken) he gobbles by the sink

and chases with a fag puffed

on the way to box, while siblings,

older, younger, scribble lessons

or meet friends; sleeps alone

above the back porch in an unheated

room; wears his brother’s hand-me-

downs; his father beats him bloody

for spending part of his first pay-

check on a first pair of new shoes;

for cash he boxes bantam weight

before crowds shrieking kill the kike,

hawks sandwiches from wooden carts

to high school kids who once were friends,

at quitting time shoots crap with men

and at sixteen, meat hook in hand,

stands in a butcher shop’s ice-box

breaking beef hindquarters down.

Depression shadowing the Volk

like a Canaanite colossus,

arms bent at elbows, palms turned up,

hefts the male offering, sublimes

skin so it no longer feels pain,

fuses eyelids so rainbows shine

in vain, sears nerves so hands cannot

unclench and a decade on, when

ritual ends, amid ashes

the sacrifice survives, savage

more than man, hard, violent,

unbelieving, in the orbit

of whose fists lie his certainties.

4

Bouts sometimes knocked him head to knees,

His swollen gut spewed crimson

Shit, he wasted until Crohn’s disease

Left his great white hope the surgeon.

Tangled in tubes and drips post-op,

Missing most of his ileum,

Ribs prominent through cotton top,

Fed strained juice and pabulum

He went fifteen rounds with death.

The dark heavyweight danced away,

Doctors raised his withered arm

And sent him south where snowbirds play

Hoping he’d recover weight and form.

There he eyed the champion

Crouched outside the ring to spring

Back for the rematch no one wins,

His belly’s serpentine stitching,

The black before, the black after.

And when again he spread the ropes

Apart, he could not see beyond

Himself and his ringside shadow.

5

The skeleton in a wheelchair props rented

tackle on the rail, stares down twenty feet

from a pier through salt subtropical air

at shoal water wavelets for blue slashes

flashing toward the bait below his float,

and misses one hit, two, a third, an inept

young butcher far from inner-city streets

recovering from surgery, too proud

to bask with codgers, too weak to walk or swim,

a sutured rag doll whose one permitted

sport is dangling blood worms from a pole.

His father’s plumb and adze, mother’s thread and pins,

tradesmen, carters, peddlers, kaftaned bearded

kin, village landsmen from Ukraine, friends, nothing

in his life smelled of ocean; but cleaver

held again, he kept on fishing. Once a week

he drove eighty miles east to prowl the sea

with charter-men, ever farther from the coast

till, white coat and meat hook junked, he trolled

ballyhoo for marlin eight hours’ run offshore.

Two score and four skiffs on, by his command

we laid him down in fishing clothes, khaki

trousers, khaki shirt, Dan-Rick on the right

breast pocket, on the left Capt. J. Burt.

Death Mask

(L.K.B. 1917–2008)

I would have cast a death mask from her head

Cooling in a bed ringed by surviving kin

If plaster of Paris drying on shrunken

Skin, dull black buttons that had been eyes

And bared grey gums could model havoc

Ninety years had wrought upon a beauty.

But how we ruin others leaves no mark

To be traced: fixing her husband’s family

Dinner bequeathed no scars to Procne’s face.

I took a twelve-inch square of putty-coloured

Construction paper, drew a pear, inverted,

Eight inches long, four wide for cheeks to flare,

Made marks for spud nose, a Bacon mouth,

Wisps of white hair, spite lines, spots,

Scissored the outline, scraped fascia from frame

Like spittle from sere lips: but I’m no artist

With stroke and scumble to express the natural

History of families in a screaming rictus.

I turned the womb shape over and wrote how

My heels rucked the kitchen rug as she dragged

Me out at five to fight a bully, and watched;

How smart she looked, fresh from the hairdresser,

Made up and gloved to shop, after she dropped

Her eighth-grade butcher boy at his weekend work;

How if lover lift a hand to caress my cheek

I flinch. Dear Spartan mother, why did you send me

To the Apothetae, alone among your children?

I sat staring in my study at the ju-ju I’d made

Then from a top shelf pulled a thick book down

From psychologies I now won’t read again,

Opened it in the middle, laid the damned thing

Between the pages as you would to press a flower,

Or billets-doux from a bad affair you can’t quite

Forget, and committed her to my high loculus.

Slowly Sounds the Bell

Nunc lento sonitu dicunt, morieris.

Now this bell tolling softly for another,

says to me, Thou must die.

Donne, Meditation XVII

A midnight ring from half a world away

Tolls my only brother’s sudden death.

Line dead, handset re-cradled, sleep returns;

I wake to find bedclothes scarcely messed.

We long were distant islands to each other –

I stood Esau to his Jacob as a boy,

My fields the sea, his tents the libraries –

DNA proved inadhesive, no gene

Sutured the rifts between us, and the news

Was less vexing than a tree fall in my garden.

We hope for more: a foetal element

Feeding fondness for our kin, a shared

Enzyme sealing first cousins best of friends,

From propinquity Gileadan balm.

But boyhood hatred, dumb decades apart,

Change blood to water, degauss genealogies;

Abel becomes Cain’s pathogen. A shrug

In the cell metastasises through

Isolate null points of the tribe into

Skull paddies and black snow in June.

Religious tapestries woven from old deities

Cannot conceal trenches we dig between us:

Ancestral chemistry stands hooded on

The scaffold, testing trap and rope for all.

It is the face on the school run who mouths

‘Hello’, a torso hunched on the next bar stool

Twice a week, a high school sweetheart back,

A man selling ceramics I collect

Dying of AIDS, whose curfews heave the clapper

Summoning tears, the shiver in the neck.

II

Certain Windows

We trail no clouds of glory when we come. We trail blood, a cord that must be cut and post-partum mess that mix with places, people, and stories to frame the house of childhood. We dwell in that house forever.

In time there will be others, bigger, smaller, better, worse; but how we see the world, how much shelter, warmth, food we think we need, whether the outer dark appears benign or deadly depend on what we saw from certain windows in that house. We may burn, rebuild, repaint or raze it, but its memories fade the least; as dementia settles in the first things are the last to go.

Despite the enduring brightness of childhood’s colors we may touch them up, sometimes garishly, to infuse the humdrum with romance as we grow old. Testosterone wanes, breasts sag, but in some, perhaps secretly in most, the adolescent hunger to allure and seduce, swagger and swash-buckle remains.

The inherent dishonesty and danger of romantic reconstruction are reasons enough to try to record as accurately as possible what we saw, if we record at all. Vanity’s subversions are another; respect for acquaintances, editor and the few readers interested in context or what appears unusual a third. Last, there is the flicker rekindling the past throws on why someone picks up pen, or brush or camera.

Childhood ended when I turned twelve and began working in a butcher shop on Fridays after school and all day Saturdays from 7 a.m. to 6 p.m., or, as we said in winter, “from can’t see to can’t see.” By sixteen I was working thirty hours a week or more during the school year, and fifty to sixty hours in the summers. This is a recollection of my pre-travailous world, of places, people and tales from childhood.

1. Ancestral Houses

Fourth and Daly

Joe Burt, my father, was born in Boston in 1916, almost nine months to the day after his mother landed there from a shtetl near Kiev. She brought with her Eva, her first-born, and Bernie, her second. Presumably my grandfather Louis, Zaida (“ai” as in pay) or Pop, was pleased to see my grandmother, Rose, or Mom, even

though she was generally regarded as a chaleria, Yiddish for “shrew.”Zaida had been dragooned into the Russian army a little before World War I broke out. Russia levied a quota of Jewish men for the army from each shtetl and these men invariably came from the poorest shtetlachim. Zaida deserted at the earliest opportunity, which was certainly not unusual, made his way to Boston and sent for Mom.

Mom and Pop moved the family in 1917 to a small row (terraced) house at Fourth and Daly streets in South Philadelphia, the city where my father grew up, worked, married and in 1995 died. Pop was a carpenter, Mom a seamstress, both socialists at least, if not Communists. Mom was an organizer for the I.L.G.W.U. (the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union), which seems in character. Yiddish was the household tongue, my father’s first, though Pop spoke and read Russian and English fluently. Mom managed Russian well, but English took more effort.

The family’s daily newspaper was Forverts (The Forward), printed in Yiddish. Forverts published lists of those killed in pogroms when they occurred. Ukrainian Cossacks allied themselves with the Bolsheviks and used the Russian civil war as an excuse to continue the pogroms that had been a fact of Jewish life in the Pale from the 1880s. Pop was hanging from a trolley car strap on his way home from work in 1920 when he read the names of his family among the dead, all eighteen of them: father, mother, sisters, brothers, their children. He had become an orphan. He never went to schul (synagogue) again.

A few years later he learned how they were killed when some of Mom’s family, who had hidden during the raid, emigrated to America. I heard the story from him when I was ten, at Christmas 1952. I came home singing “Silent Night,” just learned in my local public elementary school. I couldn’t stop singing it and went caroling up the back steps from the alley into our kitchen where Pop, putty-colored, in his mid-sixties and dying of cancer, was making what turned out to be his last visit. Zaida had cause to dislike Gentile sacred songs, though I didn’t know it. He croaked Danila, shah stil (Danny, shut up) and I answered No, why should I? His face flushed with all the life left in him and he grabbed me by the neck and began to choke me. My father pulled him off, pinioned his arms, and, when his rage passed, led me to the kitchen table where Zaida sat at the head and told me this story:

The Jews had warning of a raid. Pop’s father, my great-grandfather, was pious and reputed to be a melamed, a learned though poor Orthodox Jew. As such he was prized and protected by the community. Pop’s in-laws urged him to take his family and hide with them in their shelter below the street. Great-grandfather refused. He said, I was told, God will protect us.

The Cossacks rousted them from their house and forced everyone to strip. They raped the women while the men watched. Done, they shot them, then the children and, last, the men. They murdered all eighteen, my every paternal forebear except Pop, who died an atheist, as did my father.