8,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

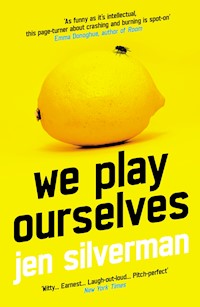

'As funny as it's intellectual, this page-turner about crashing and burning is spot-on about ambition, infatuation, theatre, film, ethics, teens, and everything else.' Emma Donoghue, author of Room 'Witty...Earnest...Laugh-out-loud...Pitch-perfect' New York Times In the pursuit of fame, how do you know when you've gone too far? When Cass - a thirty-something, promising, queer playwright - receives a prestigious award, it seems as though her career is finally taking off. That is until she finds herself at the centre of a searing public shaming, which relegates her from rising star in New York to a nobody on her best friend's sofa in L.A. As she comes to terms with the extent of her failure, she is forced to question who she is without the thing that has always defined her: her art. So she fills the days by stalking her playwright nemesis, of whom she is excruciatingly envious, and getting pulled into the orbit of the charismatic but manipulative filmmaker next door. As Cass becomes increasingly involved with her neighbour and the group of pugilistic teenage girls she's documenting, Cass begins to dream of a comeback. But when the film spins dangerously out of control, Cass is once again forced to reckon with her ambition, and her rage. We Play Ourselves is a darkly funny novel about the cost of making art, and the art of making enemies. 'Funny, sharp, modern - this is an excellent debut novel. Its bold, edgy, strange heroine has adventures and misadventures, screws up again and again, but somehow won my love. I couldn't put this book down.' Weike Wang, PEN/Hemingway-award winning author of Chemistry

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

BY JEN SILVERMAN

The Island Dwellers

We Play Ourselves

First published in hardback in the United States of America in 2021 by Random House, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

First published in hardback in Great Britain in 2021 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Jen Silverman, 2021

The moral right of Jen Silverman to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978 1 83895 430 7

Trade Paperback ISBN: 978 1 83895 431 4

E-book ISBN: 978 1 83895 432 1

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

For Dane Laffrey

Odd, for an apocalypseto announce itself with such bounty.

—KAVEH AKBAR, from “Exciting the Canvas”

We are citizens

of the countries we imagine. We make our homes in the dark.

—NICO AMADOR, from “Elegy for Two”

1

1

Iexit LAX and the warm air slaps me awake. The first thing I smell is car exhaust. Then, just under it: desert. People are already upset, a traffic cop is shouting at a red sports car and waving her arms. I think: Turn around. I think: This is not your city.

Dylan’s van is farther up. I recognize it because there is only one of its kind in the world—this is what Dylan said on the phone last night: “You’ll know it when you see it, it’s the only one of its kind in the world.” And here it is: spray-painted silver, a big gaping mouth splashed across the front, rows of jaggy shark teeth. Two big cartoon eyes goggling out at the smog. The windows are cranked down all the way, and I catch a glimpse of Dylan before he sees me: head tilted back, shaggy mop of hair, bopping along to some featureless beat. He hasn’t changed since we were eighteen. In another fifty years he’ll still look like this.

As if feeling my gaze, Dylan’s eyes snap open—electric blue—and he’s staring straight at me in the rearview mirror. “Cass!”

“Hey.”

“Welcome! Get in!”

I pull open the van door and a stink hits me. Not any smell I know. Something like tang and decay and sugar.

“Stingray died in here,” Dylan says, easy. He pulls me into a hug, ignoring the car behind us that has started to honk. “It’s so good to see you.”

“You too,” I say, as the honking becomes an urgent staccato pulse. “Should we . . . ?”

Dylan lets me go, runs his hand through my hair—“Even shorter than last time”—and pulls us out into the circular creep of traffic around the terminal. “How was your flight?”

“Good.” I crank the window the rest of the way down and brace myself for more questions—I did, after all, show up with only a day’s notice. But he’s navigating the bottleneck leading out of the airport, a frown line carving his forehead, paying exquisite attention to the road. I remember he drove like this in college too—always the designated driver.

We’re quiet even after we get onto the highway. It all seems like a strange dream: the palm trees soaring up, up, up, increasingly unlikely parabolas of trunk that explode into fronds at the top. The light is desert light, and the 105 is packed bumper to bumper; it feels like everybody is breathing in unison, barely separated by the thin skins of our cars.

I didn’t sleep last night. I left my roommate Nico a month’s rent in cash, and a note in which I told him he could sell whatever furniture was mine and keep the money. He’s in Berlin for five weeks, and I was aware, as I slipped out, that my exit was neither honest nor brave. And yet the need to leave felt clearer than anything else had felt in the past several months. Or if what I felt was not clarity, at least it was adrenaline.

I told almost no one that I was leaving. There aren’t a lot of people who would care—for the right reasons, I mean. People want to know what I’m doing about all of the messy aftermath so that they can report back to each other in low voices. Whether or not Tara-Jean Slater is suing me; if it’s true that I got tased; that cops came; that the NYPD put out a bulletin; that my agency dropped me; that I’d been arrested but my agent paid bail; that my agent had refused to pay bail, and I’m still locked up somewhere in lower Manhattan; that Tara-Jean Slater’s dad is an attorney and he got me moved to Rikers. Rikers feels like a reach to me, but then again, I’m supposed to be the one out of touch with reality, so what do I know. Maybe Rikers really was around the corner.

That isn’t why I left—I didn’t think I was going to prison—but whenever I ran into vague acquaintances, they looked surprised to see me in public. Eventually that starts to wear on you, and you stop leaving your apartment, and you become a shut-in, and the only way to jog yourself loose from your life, from every detail of your life, is to abandon it.

Other than Dylan, I called only one person last night: Liz, my ex-girlfriend. I was calling to say goodbye, because I felt like it might be strange if she ever came looking for me and I was simply gone, but before I could say anything, she was whispering furiously into the phone: “Cass, we can have coffee, sometimes, in a professional setting, but if you want to hire me for anything you should have your people call my people.” And then she paused and asked, “Do you still have people?” And that was insulting enough—in part because of its accuracy—that I hung up without saying anything at all.

I’m lost in my thoughts when Dylan says abruptly, “So, look, we’re really happy to have you, but I wanna give you a heads-up about something.”

I snap back. Stingray smell. Dylan’s eyes, blue like some improbable crayon.

“What’s that?”

Dylan clears his throat, squints at the road. “About me and Daniel.”

“Uh . . . okay?” I’ve only met Dylan’s boyfriend a few times in the decade they’ve been together. Daniel is Australian, five years older than we are. He has always seemed very serious to me, someone who has an adult job and who takes nothing lightly.

Dylan sighs. I wait for any number of possibilities to enter the space between us. Daniel and I decided to charge you five thousand bucks a month. We’re starting a cult. We perform abortions in the living room.

“Okay,” Dylan says. “Well. Daniel and I are . . . in kind of a place.” He glances at me. “It’s this whole thing about how he never planned to stay in the U.S., and how I should know that, because even when we met he always said—but the thing is, I don’t think he felt that way then. Which, maybe I just forgot, but my distinct impression was that Sydney was hell for him, because he wasn’t out in Sydney, and L.A. is like . . . you know. L.A.” This time Dylan says “L.A.” like it’s a synonym for paradise. I watch the asphalt ribbon of highway, wending slowly ahead of us, the yellow haze of polluted air hanging above it, and I say, “Uh-huh,” in what I hope is an encouraging tone.

“And now he’s all like, ‘Sydney is my home, of course I’m going back, my parents live there, my sister had a baby,’ and he was looking for jobs in Sydney—which, to be honest, I thought was a phase, because he’d go through them occasionally—but then he found a job, and he accepted it, and he bought a plane ticket, and now he’s leaving January first.”

“No way,” I say, startled. Dylan and I haven’t stayed in close touch over the years, but whenever we’ve spoken, he’s been firmly ensconced in their house, in their life. Dylan was twenty-three when they met, and as a consequence he is more accustomed to using “we” than “I.” Although I don’t know Daniel well, I think of his presence as a solid, unchanging fact. “January first,” I say. “Jesus. That’s very symbolic.” When Dylan darts his eyes from the road to my face, I know it was the wrong thing to say.

“Tickets are super cheap on January first,” Dylan tells me.

“I’m sure, yeah.”

“He also didn’t tell me any of this until he’d decided,” Dylan blurts. “I was like, Well, let’s talk about this, and he was like, I bought the ticket. Which. I think . . .” And then Dylan presses his lips together in a firm line and doesn’t say what he thinks.

We sit in silence for a long moment. The traffic has slowed to a crawl, and Dylan stares intensely at the road, as if he’s punishing it. I say: “I’m sorry.”

“It’s life,” Dylan responds automatically, as if he’s had to tell this to a lot of different people over the past few weeks. Then, as the traffic starts moving again, he takes a deep breath, blows it out, and says, as if he’s back on track with the message he meant to deliver: “So! We’re in a place where we’re figuring out, uh, a lot of things. And we both wanted you to know that coming in. So that you’d sort of—you know, if you come into the room and the energy is intense, you wouldn’t be . . .” He shrugs. “Bummed.”

“Got it,” I say. “And thanks for letting me stay right now.”

“No, no,” Dylan says quickly. “That’ll be good for us. Having a guest.” He grins with one side of his mouth. “Less screaming all around.”

“But if you do scream, I’ll consider myself well warned.”

“Oh good.” Dylan’s tone is dry.

I debate asking the question, and then can’t help it. “Do you think you’d move to Sydney?”

Dylan frowns. “Sydney . . .” he says.

I wait for a follow-up, but there isn’t one.

We turn from the 105 onto the 110, and the haze thins. Now there’s a line of mountains, like a filmy backdrop, against the densely packed city. The trees still look Jurassic, and everything is fifteen degrees hotter than October anywhere should ever be, and I keep feeling like I’m either high or in a movie about a person who has moved to L.A. Dylan fiddles with the radio knob and the background beat turns into something mournful. In New York, Tara-Jean Slater might be suing me and the NYPD might have swarmed my building and armed guards might be standing outside my former apartment door, waiting to take me away.

*

The house is a slightly ramshackle two-story, set back from the street by a narrow path. It’s painted a fading blue, and a set of low steps lead up to a wood-planked porch where Daniel stands, barefoot, watching us pull in. As soon as I get out of the van, he says: “Welcome,” and Sydney laces through that single word, flattens it out. Daniel has dark eyes and fine, long-fingered hands, and his handshake is warm and firm. He’s taller than Dylan, broader in the shoulders, with that kind of relentless good health that Australians radiate.

Dylan wraps an arm around Daniel’s shoulders, presses a kiss on his cheek. Standing together like that, the contrast is all the more striking: Dylan is Southern California sun, the brown of sunburn already turning gold. Daniel’s hair is dark, everything about his body language is contained. He accepts the kiss but doesn’t return it. I don’t remember if they kissed last time I saw them, so I can’t tell if this is “intense” or normal.

“Let’s show her the house,” Dylan says. “It’s so crazy you’ve never been here, Cass.”

“Have you ever been to L.A.?” Daniel asks.

“No, actually.”

Dylan picks up my duffel bag, and I follow obediently as Daniel points out the shadowy kitchen with its old gas stove, leading into a small mudroom with a large washing machine, and beyond that, the door to my bedroom. The bedroom is nice—wood floors, big windows facing out onto a backyard. The bed is a mattress and box spring, no bed frame, across from a large open closet with empty hangers arranged in a line. Everything in the room is old and dented, like the house itself, but generous and full of light.

“Looks great,” I say, because they seem to be waiting for something. Daniel puts my duffel down next to a battered dresser.

“Let’s show her the back,” Dylan suggests. From the kitchen, sliding glass doors open onto the small rectangle of yard my bedroom windows face. It’s hemmed by weathered wooden fencing whose many gaps reveal the neighbor’s house just beyond, and, running along the western edge, a stretch of side street. A back gate hangs off its hook, facing the street.

As we step outside, I take in boxes of herbs, potted plants, a mysterious army of things that are spiky, spotted, bulbous, shiny, flat, waxy, and wet. A large lemon tree hangs over us, branches fat with fruit. It is the only plant I recognize by name.

Daniel drops down onto a nearby lawn chair. Dylan finds a joint tucked under the ashtray on the patio table and lights it, taking a deep drag. He offers it to Daniel, who shakes his head, and then to me. I shake my head. As Dylan blows smoke out in a steady blue stream, Daniel says: “Dylan said—you’ve been working in the theatre? Are you an actor?”

“No, no,” I say hastily. I’m wondering what else Dylan might have said recently.

“Baby,” Dylan murmurs, the subtext being: You always forget what my friends do. If he googled me, does that mean he knows what I did? And if he knows, has there been pity on his face at any point in the last few hours? Did I mistake it for kindness?

“So—what? A stagehand?”

“Baby.” Once, years ago, when we were drunk, Dylan had said: “Daniel only remembers the jobs that he thinks are ‘real.’ ”

“She’s a playwright,” Dylan says softly, reproachfully.

I pick up one of the fallen lemons from the patio, turn it over in my fingers. “I’ve never seen a real lemon tree before,” I say. “It’s so wild that you just have one . . . growing.”

After a watchful moment, Daniel lets the subject be changed. “It was here when we moved in,” he says, and then, humbly, as if he doesn’t mean to brag but can’t help saying this, he gestures at the plants around us: “The rest is me, though.”

“You did this? It’s beautiful.”

Daniel smiles. It’s surprisingly luminous; it changes his whole face. “I planted them, but they did the hard part themselves.”

“No,” Dylan objects, “it’s impressive. Own it.”

“Things growing from small to large is my speed,” Daniel says, self-deprecating. And then, teasing: “Dylan prefers roller coasters and fast cars and all that American excess.”

Dylan grins, shrugs. The sun plays over the muscles of his upper arms, the cords of his neck. Dylan and I slept together once—college, of course, one of those nights that reseal themselves as soon as they’re over. We joked about it from time to time, never did it again. I remember that, when Dylan started dating Daniel, he mentioned that Daniel was a “gold-star gay”—“No women,” Dylan had said, sounding impressed, “not once.” Dylan and I each had a series of boyfriends and girlfriends over the years, and displays of singular focus were impressive to us both. As they stayed together, Dylan stopped mentioning past girlfriends, until you would have thought that his, too, was a history of singular focus. I’d never asked if he had told Daniel about us.

“Well,” Daniel says, after the quiet has stretched back out. “I’ll put the sheets in the dryer.” He gives me a nod, then vanishes inside the house. Dylan kills the joint, tucks its remainder into the ashtray. I turn the lemon over and over in my fist. This is a real object. This is a real backyard. This is a real city. After waiting a moment to make sure Daniel isn’t returning, Dylan fishes in his pocket and comes up with a pack of cigarettes. “I know, so not L.A.,” he says when I glance at them.

“You still smoke?”

“Yes and no.” He taps the pack on the inside of his wrist, extracts one. “Daniel hates when I do this, but . . . We’re all gonna fall into the ocean, so . . .”

“We are?”

“The entire plate,” he says. “L.A.’s tectonic plate is gonna detach and we’ll fall into the ocean. Daniel will miss the blessed event, of course, but we . . .” He holds out the pack. “Haven’t you heard the world is ending?”

“Yeah,” I say. “Yeah, I’ve heard that.” And I drop the lemon to take one of his smokes.

*

I went to a therapist for the first and only time when everything was falling apart. With Liz, and my play, and all of it. The therapist was younger than I wanted her to be, and her clothes were more expensive than I expected. I briefly wondered if I should have been a therapist, because then I might be sane and rich as opposed to broke and crazy.

She asked me to talk about all of the reasons that I wanted to see a therapist, and I mentioned that everything I cared about was falling apart in ways that seemed ruthless and uncontrollable. She asked me what kind of things, and I searched for the easiest answer—as an example, as something she might recognize instantly—and landed on Liz. My relationship, I said, seemed to be over, although neither of us had ended it yet.

The therapist asked me to talk about this relationship, and I immediately felt like I’d made the wrong choice in using Liz as an example. I also felt like I’d made the wrong choice in calling it a relationship. Liz was the thing I was doing instead of a variety of other things. And, as far as Liz was concerned, I may have fulfilled the same function. But it felt too complicated to explain all of that, so I started to talk, and I talked for what I remember as a long time.

I talked about meeting Liz on the first day of rehearsal, and I talked about the feeling of being at the beginning of something, like a relationship—or a play—that wild rush of possibility breaking over you all the time, even when you’re brushing your teeth, even when you’re trying to sleep. How actually you just stop sleeping those first few weeks of rehearsal, because this crazy energy is being generated by all the bodies in the room that are inhabiting the thing that you dreamed up. How it’s like being possessed by ghosts, except you’re the ghost and everybody else feels suddenly so real—you’ve never been this invisible and this alive at the exact same time. It’s a baffling, terrifying, addictive feeling. It’s the best high in the world. The other thing about it is that it feels a lot like religion. I wasn’t raised with any, but the people I know who believe in God derive a lot of comfort from the idea that they are being held by something larger than themselves. When I’m in a theatre I feel held. I feel simultaneously very safe and like something very dangerous is about to happen, and that dangerous thing is the wall of my chest peeling back—slowly, so slowly, in time with the curtain rising. And if the play is my play, then everybody present can gather close and peer at my naked heart. And I won’t even try to guard myself, because I am being held by the architecture of the theatre, by every pair of arms in every seat, and I will sit still for a time between 75 and 120 minutes, and I will be naked, and I will be invisible, and I will be entirely seen. And all the parts of me that are ugly and lonely and horrible and sad will be the parts of me that other people hold close to themselves and find a secret resonance with, and about which they say to themselves: I know that thing too, when I’m all alone that’s how I feel too. And even if nobody says those words out loud, right then, we will be feeling the same feelings so strongly that we will forget that we aren’t of one body, one mind, one tenuous heart. And if it isn’t my play, then I will still be part of that collective witnessing organism, still be a single cell within a warm and gazing animal. It’s the sort of feeling that becomes a constant longing. It’s the sort of longing upon which you build an entire life.

After a while, the therapist broke in. She said, “Cass. Cass.” I remember she was looking at me oddly.

I said: What is it?

She said: You haven’t been talking about your girlfriend at all, Cass. Are you aware of that?

I said: What are you talking about, of course I’ve been talking about my girlfriend.

And the therapist said: No, you’ve been talking about the theatre.

She said: I would say you’ve been talking about your career, except none of this is about anything I would normally term a “career,” you don’t seem to have any separation between yourself and your “job,” your “employment,” so to speak, there’s no professional distance, you haven’t even mentioned the word “money.”

She said: Honestly, I would never usually put it like this, but I’ll just say it—you’re in a dysfunctional relationship with the theatre. Your girlfriend, Liz, is beside the point.

I said: I’ve been getting around to telling you about Liz, I just haven’t gotten there yet.

And the therapist said: Well, this is the first time in sixty minutes that you’ve mentioned her name, Cass, so I think that should tell you something, because it certainly tells me quite a bit.

*

My first night in L.A., I lie in bed and have a conversation with myself about my new life. The sheets smell like Meyer’s laundry detergent and lemon and sunlight, and I say: Self, you are going to look so skinny and hot. You are going to have great arm muscles, and a tan, and new jeans, and maybe some new ink. This life is going to be so good for you.

I say: Self, nobody knows who you are or what you did. From now on, you will only be around civilians who think “off-Broadway” sounds like directions to nowhere. Nobody you encounter will ever have heard of you, and you are going to be happy.

I start to hear voices filtering down through the pipes. Dylan and Daniel, upstairs. Is their bedroom directly above mine? The tour hadn’t extended to the upper floor of the house. Dylan’s voice, stacking tone on top of tone, the voice of somebody making a detailed but reasonable argument. Then Daniel’s voice, low and soft, disagreeing. Then Dylan’s again, stronger.

I get out of bed. It’s not like I’m eavesdropping. I walk over to the window. I’m taking in the backyard. I’m looking at the moonlight. If my ear is directly to the pipe, it’s just because I’m leaning on the wall. And right then, staring out the window, I see a group of shadows moving purposefully off the street and toward the back fence of the house next door. I blink. The shadows separate into hoods and jeans, sleeves, the glint of a white-soled sneaker. Teenagers, it looks like—five or six of them. As I watch, they scale the back fence of our neighbor’s house and, one by one, drop down out of sight. I’m briefly paralyzed with possibility. Am I witnessing a break-in? The precursor to homicide? Is this like the movies made by disaffected Germans, in which teenagers arbitrarily torture and murder middle-class heteronormative family units? Should I be calling Dylan? Or the neighbor? Or the police?

The last of the bodies, enswathed in its hoodie, drops over the back fence. The shadows are gone. The night is quiet. I stand very still, no longer trying to hear Dylan and Daniel’s argument—instead, I listen for the sound of screams, pleading, duct tape being pulled to cover someone’s well-intentioned, fatherly mouth. But the silence is broken only by the hush of cars passing by on Fountain Ave. Even Dylan and Daniel are no longer talking.

After enough time has passed, I go back to bed. The mattress is firm and the pillows are soft. I can usually sleep anywhere, it’s my superhuman skill, but somehow in this comfortable bed, in this large, calm room, I’m jumpy. Whenever I close my eyes, all I can see is the highway speeding wildly past, trees careening, hills swinging right and left, even though Dylan drove it so slowly earlier that day. I lie awake for a long time, eyes wide and dry, listening for the sound of something somewhere happening to someone before it happens to me.

2

My first week in L.A. is long and strange—simultaneously a repeat of certain basic activities (wake up, make coffee, drink it on the patio, check email, shower in the light-filled downstairs bathroom) and a barrage of smells and shapes that I have no context for. Fruit trees so overburdened with fruit that the sidewalks are littered with it; big squashy-blossomed shrubs; armor-plated cacti; homeless encampments comprised of dust-encrusted outdoor tents, shopping carts piled high with garbage bags.

In New York it gets too cold to be outside all the time, you can’t build yourself a city of tents and shopping carts. In L.A., whole private lives are happening in public spaces: cooking, sleeping, laughing, talking, hanging out laundry, reading battered paperbacks. The homeless people ignore me and I try to ignore them, but part of me feels like they’re ignoring me because they’ve all heard about me, and they’re signaling to each other: Don’t look at her, failure like that is contagious.

Daniel isn’t around in the daytime. I learn from Dylan that he works a regular nine-to-five for a company doing something called “risk management.” I don’t know what risk management is, other than a tidy summation of everything I’m bad at. Dylan was an English major in college, which means that he works at a restaurant in Los Feliz. But the thing that Dylan really devotes himself to, with the determination that other people bring to their jobs, is lounging. He’s always in the sun on the patio with his shirt off, throwing his surfboard into the back of the van, returning from the beach with his wetsuit peeled down to his hip bones and his shaggy hair damp and salt crusted.

I gather that this—like the cigarettes—is a subject of contention between the two of them. It seems that there are a number of these, but I have entered at a time of tenuous détente, so I try not to ask questions that they will then have to try not to answer. This is a state of affairs with which I’m well acquainted.

On the afternoon of the third day, I call my agent. Before I left New York, Marisa had said, “Don’t call me again,” in the same conversation in which she’d used the phrase “appalling and unprofessional.” I think it was also the conversation in which she said something about me being lucky I wasn’t getting sued, and also something about this sort of bad-boy behavior not being cute anymore post–Sam Shepard. I don’t remember the conversation entirely, because I was drunk at the time—I hadn’t planned to be, I had only happened to be drinking heavily when Marisa decided to call me back. And now that it’s already sort of fuzzy, I try to maintain as much fuzziness as possible, because I can’t be responsible for knowing what I don’t remember. Maybe in the light of day, in the light of L.A., we can have a new conversation. America loves a comeback story. Think of Britney. I know I’ve only been gone a few days, but who says how long you have to be gone before you’re ready to come back?

So I call Marisa. Her assistant picks up immediately: “Creative Content Associates, how may I help you?”

“Hey,” I say, trying to sound very casual. “Uh, is Marisa in?”

“Who’s calling, please?”

“It’s Cass.”

And: a beat, wherein the assistant tries to figure out what to do. Here is what you need to know about this assistant: Jocelyn / twenty-two / ironic polka dots / parents on the UWS / scarlet lipstick / first job out of Barnard.

After a moment, Jocelyn says, her tone slightly cooler: “One moment, please, let me see if I have her.” This means: She’s here, but which will she kill me for: hanging up on you, or transferring you over?

Silence, and then Jocelyn returns. “I’m so sorry, I don’t have her at the moment. Can we return?”

“Yeah, please . . . uh, return.”

“Okay, thank you so much for calling.”

Jocelyn is about to hang up when I hear myself blurt: “I moved to L.A., will you let her know that I moved to L.A.?”

Jocelyn draws breath, but before she can answer, I amend my request: “Actually don’t say I moved, just tell her I’m in L.A.”

“Okay,” Jocelyn says. “Well, thank you—”

“—and tell her I don’t remember what she—on the phone, what she said? What we said? So if she thinks I remember all of it, maybe tell her that actually isn’t the case, so I’d love to sort of . . . reconnect and reexamine. . . . Hello?”

Click. Jocelyn and her scarlet lipstick have hung up.

*

The Lansing Award was what put me on the radar. And it went like this.

Pre-Lansing, I was nobody. I grew up in small-town New Hampshire, went to a college that was affordable instead of fancy, and moved to New York, where I was immediately broke as balls. I paid my bills by grant writing, dog walking, and cater-waitering, in various combinations. I made weird downtown plays and got my friends to put them up in black-box theatres, basements, or found spaces. I had an unshakable conviction that someday I would hit the “tipping point” (this was something a psychic on West Fourth once told me), after which my career would take off. Everything up to the tipping point would be the story I could tell once things had worked out. My unshakable conviction could be seen as either ambition or delusion, depending who you were (the psychic referred to it as a calling), but either way, it made it easier to work three jobs and self-produce experimental plays.

And then one day, in my tenth year of this New York life, a man called and told me I’d won fifty thousand dollars and I had to show up to the Harvard Club for a ceremony, after which I could collect it.

At first I thought this was a scam, but the man kept going. He told me that it was an inaugural award for emerging playwrights. Two others had also won, and he named them, so I googled them. Tara-Jean Slater was finishing her last year of undergrad at Yale, and she seemed to have already won most of the awards that Yale itself had to offer. In the pictures, she looked very young and blank, and pretty in a prepubescent way. Carter Maxwell was straight out of grad school at Juilliard (he’d done his undergrad at Yale), and his mother was an accomplished interior designer on the Upper East Side. He had recently attended his sister’s wedding in Hyannis Port, and he looked dashing in a suit—both in the wedding pictures and in a recent New York Times profile that called him “possibly the next Arthur Miller.”

I called my roommate at work and asked if I could borrow his suit.

Nico was taller than me, but we shared a similar build. We’d lived together for the last four years, and neither of us were ever home, which made our situation work well. Nico was a choreographer. His dad was from El Salvador, his mom was a New York Jew, and both were musicians. Although they’d divorced while he was young, they still lived down the street from each other in Berkeley, and regularly reconvened for family Thanksgiving. Nico was well-adjusted in a way that defied belief; he did his laundry weekly, he saved money, he paid his taxes on time, and he was always lending me clothes.

The day of the ceremony, I borrowed Nico’s blue suit jacket and I put it over skinny black jeans and black Chucks, and I took the subway from 168th Street down to Forty-fourth, then walked east toward Fifth Avenue. I walked around the block three or four times before I got up the courage to go in. After the final lap, I took a deep breath, held it until I felt a little high, and then marched over to the entrance. A woman with a clipboard got my name: “Oh! You’re one of the honorees! There’s a table over there, please get your name tag and then, if you wouldn’t mind, there’s a step-and-repeat by the—”

I didn’t make it to either the name tag table or the step-and-repeat. There were crowds. There were cocktails. Open bar. Small glasses of wine circulating on trays. I’d fallen into a blur of dark wood and elegant fabric and chardonnay. I realized that nobody was wearing what I was wearing. I realized that everyone had a plus-one, and I should have brought Nico as well as his suit. I caught a glimpse of Carter Maxwell, who had a girl in a silk dress on his arm. Carter was shaking hands with a series of older men, also in suits, and saying things like “Such a pleasure” and “You know, that’s a good question” and “Well, thank you sir, I appreciate that” and “Very recently, but it’s nice to be out of school.” He held his drink effortlessly, and when the time came to put the empty glass on a tray and receive another drink, he did that effortlessly as well. I was having trouble just standing in the room. It seemed that either everybody was staring at me or I was completely invisible. I had wanted this forever, to be in a room like this, and now that I was here, I felt light-headed and nauseous.

Eventually I stumbled down a series of hallways and a woman pointed me to the ladies’ room, where I hid in a stall and texted Nico.

I said: This is awful, I’m gonna puke.

Nico said: Get that monayyy. Nico in person is innate elegance, but Nico over text is a whole different story.

I said: Nobody is talking to me

I think maybe I’m dead and/or dreaming this

I dunno how to get the food off the trays

like, with your fingers? or like

also nobody is wearing jeans

Carter’s girlfriend looks expensive

Can I go home early do you think?

Nico said: This is your TIME to SHINE.

I said: I’m gonna puke on your suit.

Nico said: Get my money get my cash get my math everything’s funny til that ass gettin trashed—which I stared at for a few minutes, trying to decipher, until I realized it was Nicki Minaj lyrics.

I exited the bathroom stall, flagged down a caterer, and drank two glasses of wine in the span of ten minutes, and a relaxed curiosity unspooled itself inside me. I bobbed along, now just a pair of eyes. If people glanced at me, I looked back, friendly but noncommittal. Carter was near the bar, laughing as a middle-aged man slapped him jocularly on the back—I couldn’t hear them, but I could tell that he was deflecting a compliment with expertise. His girlfriend had clearly gotten tired of this; her mouth was fixed in a smile, but her eyes had traveled over their heads, across the crowd, out and away. Her heels were hurting and the room was hot, and Carter was no longer introducing her to people, because they were happening to him so fast he didn’t even know their names. He didn’t seem overwhelmed or nervous, though. Maybe he’d always expected to be in a situation where he was being rewarded for his promise, and so he was prepared. I had imagined a Big Break for so long but hadn’t known that it would have the power to undo me when it arrived.

I drifted over to the bar. Carter glanced up, took me in.

“You must be Cass,” he said.

I glanced down at the front of Nico’s jacket, found it blank, and then remembered I’d never visited the name tag table. “How’d you know?”

“You look like a Cass,” Carter deadpanned, and then he grinned. “I googled you.”

“You did?”

“Yeah, I’d never heard of you.” He said it like it could be either an insult or a compliment.

“I’d never heard of you either,” I said.

Carter grinned again. “Congrats are in order for all of us,” he said. “We’re emerging.” He lifted his glass, then saw I didn’t have one. The bartender was at the other end of the bar, a situation that had baffled me—does one wave a hand in an establishment like this? Do you shout louder than the ambient noise?—but Carter reached out languidly and snagged a glass of white wine off a passing tray that I hadn’t even clocked. He sniffed it, shrugged, handed it to me. “Bad pinot, I think? Cheers.”

We toasted, we drank. I studied Carter over my wineglass. The room had gotten overfilled, and you had to lean in and yell to be heard. He was scanning the crowd with mild interest, but he included me in it—“Oh, Playbill is here.” And then a moment later, “Oh, Tony Kushner is here.” And then: “Oh, Marsha Norman is here.” I risked a glance at the room, but it threatened to become a blurred mass again, so I focused on my glass.

“Have you met Tara-Jean Slater yet?” Carter asked.

“No,” I said.

“Me neither, but I’m looking forward to it. I keep hearing about her.”

“You do?”

“Yeah, she’s like—a big deal in New Haven.” Carter laughed. “The Yale network, you know.”

I didn’t know. Instead, I asked: “How does this kind of thing go?”

Carter glanced at me. “You mean big picture? You should talk to your agent about that.”

“No, I mean like—right now, what’s gonna happen?”

Carter shrugged. “There’ll be a bunch of speeches, then we go up and say some words, and they give us a check.” He turned to scout out the far corner for more people of note, then turned back to me: “You’ve done this before, it’s like all of them.”

“I haven’t,” I said. “Actually.”

“Done this before?”

“Yeah.”

“Oh.” Carter seemed surprised. “I just figured . . . you know, people usually win things because they won other things.”

“I’ve never won anything in my life,” I said.

“Oh.” Carter gave me his attention in a real way now. “Who’s your agent?”

“I don’t have one.”

Now Carter was really staring. “Like, you’re between agencies?”

“I never got one.” I shrugged. “I’ve been—you know, doing stuff downtown.”

Carter opened his mouth, but then his girlfriend appeared, smelling floral, and I let the crowd swallow me back up. I wasn’t sure whether I felt ashamed for not having and knowing the things Carter seemed to have and know, or whether I felt floaty and warm and like I didn’t give a fuck. The fourth glass of wine was nudging me much closer to floaty and warm, and I was contemplating a fifth when the crowd started moving en masse toward the hall and into a different room, as if they’d all heard a whistle that I couldn’t hear.

The ceremony itself was what Carter had predicted. I don’t remember much of it, because floaty and warm turned into definitively drunk. I didn’t absorb what was said about us in the speeches either, but later I looked it up. Carter had won because of his raw and authentic dissection of male-female relationships and his insights into how masculinity functions within shifting power dynamics. I was selected as a promising female voice, a young woman telling comedic and timely stories about young women. And Tara-Jean Slater . . .

I’m not ready to talk about Tara-Jean Slater.

We were called to the front one by one. Carter talked for a while. I remember watching his girlfriend unobtrusively check her phone a few times, before he walked offstage to thunderous applause. When he reached his seat beside her, she was beaming at him as if she’d been hanging on every word.

My memory of seeing Tara-Jean Slater for the first time is blurry. She was wearing velvet overalls and yellow shoes, and her hair was in two tight pigtails the color of rust. She had a very tiny, very clear voice, like a thimbleful of water. Sometimes I wish I could remember what she’d said, but I was drunk, and I didn’t know she mattered.

Someone told me later that when my name was called, I walked to the front of the room, blinked at them all owlishly, said, “Thank you,” and then walked back to my seat, completely forgetting to collect the check. One of the facilitators had to chase me down the aisle and hand it to me. I don’t remember this, but I do remember that I passed Carter after the ceremony ended, and he gave me a thumbs-up and said, “Short and sweet.”

I went home and fell into bed. Woke up hungover and couldn’t remember why for a few minutes, until I found Nico’s suit jacket on my floor with a check for fifty thousand dollars in the pocket. I went to the bank, deposited it, paid my rent, and then after brief thought, paid the next month in advance. Brought Nico’s jacket to the cleaners, met him for burritos to soak up the remaining toxins. By the time I’d made it back to our apartment, my hangover was fading and the Lansing Award ceremony seemed like it had happened years ago.

The next day there were pictures of me on Playbill and on Theater-Mania and in the Times. I googled myself and there I was: fragmented into frame after frame, intoxicatingly real. In all the photos, I looked startled, like an animal on the highway at night; Nico’s jacket was big on me, and the powder blue stood out oddly against everyone else’s sleek grays and elegant blacks. I hadn’t even won spelling bees in middle school. I had assumed that someday I might win something and it would be nice, but this sensation was to “nice” as “amphetamine-fueled bender” is to “party.” I started to read all the good things being said about me online, and I felt that they must be true, and I was dazzled by how talented I had been this whole time. Despite the many years of uncertainty, despite all the dog walking and downtown-low-budget-play making, I had actually been the insightfully comedic voice of my generation. I read about myself for hours, long into the afternoon, and when I thought to check my phone, I saw that Dylan had texted me Whoa fancy, and my mother had texted me What is a Lansing Award? and Nico had texted me, from the next room, Nice suit jacket where’d you get it, and the next day Marisa called me, asking me to meet with her, and then the day after that I had an agent and a reputation and a career.

*

Because I have no idea what I’m doing in L.A. other than not being in New York, I spend the whole first week rattling around the big Silver Lake house. I try to stay off the Internet for fear of what I will see about myself; when I do go online, I find myself seeking out bad reviews of other people’s plays. I write down the worst bits on Post-it notes and stick them to the mirror in my bathroom, so that when I wake up in the morning I am immediately surrounded by starbursts of disaster that are not my own. When I brush my teeth or wash my face, I read “Remarkably unfinished and uneven” and “A surprisingly banal attempt at . . .” and “A very, very little play that manages to last three hours nonetheless . . .” and I think: Someone else somewhere is suffering.

I try Marisa again at the end of the week. I’m waiting in the line outside La Colombe on Sunset Boulevard. The girl in front of me has tattoos of pinup girls on her shoulders and back, and when a light breeze blows over us, she says to her boyfriend, “Oh my god, it’s arctic.” A surprising number of French bulldogs are walking past, and they all seem jaded.

“Creative Content Associates, how may I help you?”

“Oh, hey, uh, Jocelyn? Is Marisa in?”

She knows it’s me. I know she knows it’s me. But she has to ask: “Who’s calling, please?”

“It’s Cass.”

Did she sigh? Maybe not. It’s loud out here.

“Hi, Cass,” she says, very professionally. “I don’t have Marisa right now, can I have her return?”

“Uh, do you know when she’ll be back?”

“No, I’m sorry. But I can take a—”

“Is she like, out out, or is she like, in a meeting but in the office?”

“I’m sorry?”

“Because I just need to talk to her for a second. Say three minutes, five max. So if she’s actually at the office, maybe—”

“She’s unavailable,” Jocelyn says firmly. The tone of her voice says she is trying to remind herself that this is her first job out of college and she has to be good at it.

“Okay, well. Did you give her my message?”

“Yes,” Jocelyn says, in a tone that tells me, No.

“Jocelyn,” I say desperately. “Be honest with me.”

But instead of sounding desperate, I sound stern. By total accident. Maybe this reminds her of the time a college professor called her out on her bullshit, or maybe it’s a flashback to being yelled at by an older sister, but whatever it is, she gets defensive and deferential. “I gave it to her but like, I’m not in control of her schedule? And like, there’s a lot of people on the phone sheet right now? So, if she’s not calling you yet, that doesn’t mean I didn’t give her your message?”

“Okay,” I say soothingly. “Okay, I hear you. You’re doing a good job, Jocelyn.”

“Thanks,” she says, muffled.

“Can you just do me one more favor?”

“What is it?”

“Can you tell me if Marisa is around this afternoon? Like, if somebody called—somebody, for example, who wasn’t me—would she be around?”

Jocelyn knows she’s being asked to step into dangerous territory. “Marisa has meetings all afternoon,” she says carefully.

“Uh-huh . . .”

“For most of the afternoon.”

“Right.”

“Around three p.m., she has eleven minutes between meetings.”

“Okay.”

“Whether or not she’s around during those eleven minutes is complicated, depending on whether or not she goes to the bathroom during those eleven minutes, or goes outside, or gets a coffee, or has me get her a coffee.”

“Thank you,” I say, trying to be casual and fervent at the same time.

Jocelyn’s voice firms up, gets more profesh again. “Would you like to leave a message?” Someone must be walking by.

“No, thank you,” I say, and I hang up. Another French bulldog saunters past. It gives me a languid, scornful stare. It knows I can’t even get my agent on the phone. It’s never been less impressed, except for the last time it was in Silver Lake and some low-rent asshole was making desperate calls outside an overpriced coffeeshop. Sooo sad, says the French bulldog, and pops a squat by the taco truck.

*

I have two and a half hours to kill. It’s not even noon in New York. Theatre people are nocturnal. L.A. is intensely, aggressively diurnal.

I sit outside La Colombe and I watch people biking vehemently—not to work, necessarily, but to their next yoga class, or their early meditation session, or to the place two blocks up called, simply, JUICE. I itch for a cigarette. Dylan warned me that smoking in L.A. is basically the same thing as skinning a baby seal. He told me that he only smokes in the backyard, and when people ask him if he’s a smoker, he says no. I hold my pointer and middle finger below my nose so I can smell the soothing residual tobacco scent, and I practice what I’ll say to Marisa.

Hi, Marisa. It’s me, Cass.

Yes, it’s lovely out here.

Listen, I know it got rocky. And I take full responsibility for that. But, look. It was a wake-up call. I got my head together. Meditating, green juices, spin classes . . .

Then I’ll go in for the kill. Here’s the thing, Marisa. At the end of the day, all these new offers I’m getting? They don’t compare to the trust we had.

Maybe that’s too strong. Maybe this is a terrible idea.

I call the office at three p.m. Jocelyn doesn’t pick up. The phone rings and rings. I call back eleven times between 3:00 and 3:11. That’s once every sixty seconds. Each time, nobody picks up. At 3:12, I know that Marisa is now definitively in her next meeting. I consider sending Jocelyn a really nasty email, but instead I take a deep breath and practice visualizing positive things. I visualize Jocelyn leaving the agency in her strappy high heels and getting hit by a cab. I visualize Jocelyn getting hit by a truck. In my visualization, Jocelyn gets hit by a series of vehicles and is finished off by a horse-drawn carriage, the kind tourists ride in. I watch Jocelyn’s high heels fly up in the air and her hair blow back. I feel positive.

*

I was with Nico when Marisa called to tell me that my play was getting produced off-Broadway. Nico’s college friends were visiting, and we were sitting around the living room while they reminisced over entire adventures that I’d never heard about—road trips to Montauk to scatter the ashes of somebody’s dead dog, the time that they went to a gathering of Radical Faeries. A skinny lesbian was launching into a story about how she’d walked the High Line recently with her Iowan cousin, who kept calling it “the Skyline,” when my phone rang. Marisa, Creative Content Associates came up on the screen. I’d recently become one of those people who said things like “I’m so sorry, I have to take this, my agent is calling.” I’d never been able to say this sentence before, and now that I could, I never wanted to stop saying it. But when I delivered my line, nobody noticed and the skinny lesbian kept talking, so I stepped into our kitchen.

On the phone Marisa was cheerful and forceful in equal measure. Talking to her always feels like being run over by a tank, even when the tank is going in the same direction you want to go. “Gotta jump, so, real quick,” is how she begins most phone calls. This one was no exception, except she followed it with: “You got your off-Broadway debut. Congrats!”

“Wait, what?”

Marisa told me that she’d recently gotten off the phone with a large and well-known Midtown theatre. “They had a play fall through for their first slot, so they read this year’s crop of Lansing playwrights, and they love your play. Rehearsals start August, play opens September. Yes?”

“Oh,” I said. “Oh wow.”

“What else, what else.” Marisa ticked her pen against her teeth—I’d seen her do it in person by then, so I knew what the click, click over the phone was. “They want to have Hélène Allard direct—she was set to do the other play.” She said the last name “Al-lar”: very French.

“Uh, okay.”

“I said you’d have to meet with her, of course, so we’ll set that up. She’s great, she’ll be good profile for you.” Click, click. “There’s been a lot of buzz. The Lansing and now this—everybody’s talking, they’re like, Where did she come from?”

“I’ve been here,” I started to say. “For ten years, actually—”

But Marisa didn’t hear me. “This is your moment, kiddo. Congrats! So, gotta jump. Call you later when we have the paperwork.”

She hung up, and I sat on the floor. Nico came in and found me there.

“You okay?”

“Yeah, um—I’m having a play produced.”

“Congrats! Are you guys using Judson Church again?”

“No,” I said, and then couldn’t stop myself from dropping the name of the theatre like a bomb. Nico’s eyebrows jumped.

“That’s crazy,” he said. “That’s amazing!”