Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Bangkok, 1980. As the decades pass, figures fall in and out of the relentless city: Pea and Nam, who arrive in search of a better life; a Thai Elvis impersonator and his only daughter, Pinky; Benz, Tintin and Big, a brotherhood of orphaned strayboys; Rick, the white American patriarch who abandons his Thai family when the going gets tough; Hasmah, whose bloody, hidden work is driven by secessionist rage. Sex tourism, Buddhist cults, gambling rings and skin-whitening routines threaten to take over a city reeling from financial crisis - in a nation constantly reinventing itself, anything can happen. In the temples, slums, and gated estates of late-twentieth century Bangkok, Welcome Me to the Kingdom exposes the schemes and strategies, the lies and betrayals, that inch its characters tantalisingly closer to 'the good life'. Wildly imaginative and ambitious, Mai Nardone's immersive debut announces the arrival of an extraordinary new voice, and captures the growing discrepancy between Thailand's smiling self-image and its ugly reverse. Seen through a haze of covert agreements and cigarette smoke, these unforgettable stories capture a kingdom caught between this world and the next.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 419

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

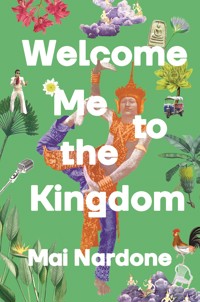

Welcome Me to the Kingdom

First published in the United States of America in 2023 by Random House, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

Published in hardback in Great Britain in 2023 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

This paperback edition published in 2024.

Copyright © Mai Nardone, 2023

The moral right of Mai Nardone to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Some stories are previously published: ‘Stomping Ground’ in American Short Fiction, ‘Like Us for a Whiter You’ in Apogee, ‘English!’ in The Bridport Prize Anthology 2013, ‘Easy’ (as ‘Only You Farang Are So Easy to Come and Leave’) in Catapult, ‘Exit Father’ in Granta, ‘Captain Q is Dead’ in Guernica, ‘What You Bargained For’ in Kenyon Review Online, ‘The Tum-boon Brigade’ in McSweeney’s Quarterly, ‘Welcome Me to the Kingdom’ in Ploughshares, and ‘Goodbye, Big E Bar’ in Vol. 1 Brooklyn.

This collection is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN: 9781838958312

EBook ISBN: 9781838958305

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An Imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

Contents

PROLOGUE

LABOR

Pea & Nam (1980)

WHAT YOU BARGAINED FOR

Rick, Nam & Pea (1980)

PINK YOUTH

Hasmah & Nam (1982)

EXIT FATHER

Ping (1985–)

PARADE

Lara, Nam & Rick (1991)

STOMPING GROUND

Benz, Tintin & Pradit (1993)

GOODBYE, BIG E BAR

Pinky & Pradit (1996)

EASY

Lara, Nam & Rick (1997)

FEASTS

Ping, Pinky & Pradit (1999)

CAPTAIN Q IS DEAD

Benz & Tintin (2000)

MAKE-BELIEVE

Pinky (2010)

LIKE US FOR A WHITER YOU

Lara & Nam (2010)

HANDSOME RED

Tintin (2011)

WELCOME ME TO THE KINGDOM

Lara & Benz (2013)

CITY OF BRASS

Jimmy & Ping (2016)

ENGLISH!

Pea & Nam (1974)

THE TUM-BOON BRIGADE

Benz, Tintin & Lara (2014)

Acknowledgments

Welcome Me to the Kingdom

Prologue

We came with the drought. From the window of the train, the rich brown of the Chao Phraya River marked the turn from the northeast into the central plains. We came for Bangkok on the delta. The thin tributaries that laced the provinces found full current at the capital. And in the city, we’d heard, the wealth was wide and deep.

The train arrived alongside trucks hauling into the outskirts, flames painted on their fenders, bumpers lined with Michelin Man dolls. The fanfare of a conquering army. And the city received us with familiar faces, celebrities we knew from Channel 7 smiling from the gauntlet of signs, promising the best in soda, soap, and gold.

We came with our own talismans—jade, bronze—protections against a city that didn’t live up to our expectation: just this? In the station, no one seemed to be boarding the trains. They sat waiting, surrounded by the tourism banners. Take Home a Thousand Smiles. This, too, we read as a promise.

Labor

PEA & NAM (1980)

The coins Pea wouldn’t spend had worried a hole through his pocket, so he was jingling them in his fist as he passed the pawn shop that sold foreign liquor by the shot. The bottles were dusty, proof of another life in some formerly rich man’s cabinet.

“Always the last to go, the liquor,” the old pawnbroker said to Pea. “You know when they bring the whiskey they’ve hit the bottom. Sell their wives first, most of them.”

“This is the real stuff, right?” Pea asked. “You’re not just reusing the bottles? I know the taste of Mekhong.”

“You tell me.”

Pea drank. “Fucking gasoline.”

“It’s from Kentucky, USA,” the old man said, holding the indecipherable label out to Pea.

“Well, in Kentucky, USA, they must use this to run cars.” Pea spread the rest of his money on the glass cabinet. “Another?”

NAM HAD GIVEN him a deadline: thirty days. That was how long he had to make them a living. Tucked in Pea’s breast pocket was a page from a free Chinese calendar, the numbers smudged by sweat. Sixteen inky days already blued away by his thumb. Sixteen days since he and Nam had come down on the train together, down from the northeast to Bangkok. Since then, Nam had been staying with her last living kin, a cousin, while Pea roomed at a boardinghouse apartment with other men from the provinces, what counted to him now as family. They worked security, gardening, driving—all of it better than the wet suck of the rice paddies in the northeast, the shining white flats of the salt pans along the coast, the hot pools of the shrimp farms across the central plains. The men had traded that work for slow days and shade, for nights sharing food on the plastic mat, talking women and money, pooling their daydreams. Pea contributed what he could, except his worry for Nam. He needed her to himself. Sixteen days spent.

“Nothing, kid?” the other men asked daily of Pea, the newest among the six that shared the main room. The landlord had the bedroom, which was air-conditioned, and standing at the door Pea could feel the cool air gracing his toes. He had never seen the room, but in two weeks had come to know the life of its sounds, the frequent ding! of the microwave and enduring patter of a TV, which during the day ran Chinese soaps and at night porn that kept the other men awake with longing.

“He updates the video monthly,” one boarder had told Pea. “But this month it’s a squealer.”

Pea could hear it wasn’t Thai.

“French,” the man said. “He likes the farang women.” His hands cupped imaginary breasts. “Bigger, you know?”

For two weeks Pea had listened nightly to the same movie, counting down the VHS’s two-hour capacity. And when he couldn’t bear another performance, he forced himself outside.

Which is how he found himself, on night sixteen, hovering by a flower market, drawn there by its fluorescent sting, by the ant line of laborers shuttling huge cane baskets. There was a buyer, too, marked by his good shoes, the way he skirted puddles. Pea looked for a foreman. He was looking for work.

The market was busiest after sundown, without the daytime heat on those neat flowers in foam boxes, petals spritzed, glistening like first-world candy. Not the thorny, twisted sentinels of the up-country temple where Pea was fostered, here was something imported from a lush planet.

“China,” a laborer told him. He said the blue anchan and white jasmine buds were local, but the roses and orchids came from abroad.

Pea said he needed work. Anything.

The man gestured. “That’s the boss in the blue.”

Soon after, Pea began a hard night lugging flowers by the kilo and basket from truck bed to stalls, bearing supplies for the wreath-makers—two lines of women with pincers for fingers threading jasmine buds onto long needles. When he finished that, the foreman had him packing ice. He was the only worker without a cart to trundle the weight, so Pea managed on his back alone.

At the end of the night he stood at attention before the boss, heels together. He wanted to look tidy, fresh, but his hands were blue from the iceboxes, left shoulder soaked where it had borne the ice sacks. The man counted out Pea’s pay twice, rubbed each bill between his fingers and splayed them on the table.

Pea picked up the bills and made a show of looking around the room. “How much are you paying these men?” he asked, gesturing.

“Don’t worry, boy. You’re all paid the same.”

Pea divided his money and laid half of it back on the table. “Yeah, well, I’ll work twice as hard as them for half the pay if you’ll hire me full-time.”

“How old are you?”

“Twenty,” Pea lied. He could barely pass for the eighteen he actually was, but the man gave him the work anyway.

On his way out of the warehouse Pea saluted the laborer who had first ushered him in. Then he tucked a vine of bougainvillea under his shirt for Nam. Only, by the time he got them to her, the papery flowers had turned to pulp in his palms. She liked them, she assured him.

“Let’s have breakfast at that stall you like,” he said. “My treat.”

The sun had risen by now, but the city buildings, wreathed in smog, eclipsed the show. He paid extra for one egg each to stir into the murk of their porridge. “Flowers like you’ve never seen before,” he told Nam. “The expensive ones they keep in refrigerators, like food.”

She twined the bougainvillea in her fingers and picked at her porridge.

Pea shook white pepper into his, then vinegar and soy sauce. He offered her the condiments. “No? You want it plain like that?”

She wasn’t hungry.

“But eat the egg at least.” He didn’t want to remind her of the price of food. Three weeks into the monsoon season and still no rain. Even in Bangkok people looked hopefully at the clear skies.

“You look tired,” he said.

She had been dragging this mood around ever since they arrived, by turn worried or distant. She asked about his fellow boarders and he passed her details, never mentioning the landlord. Not that Nam wasn’t used to him relaying sex talk. The lives of temple boys back in the northeast was sex talk. Nightly the boys paraded past the one sex bar on their side of town, a karaoke place with tinted windows and an English sign: Happy 2 You. Thumping and hooting, the boys would romp by, tripping one another in front of the door, hoping it might swing in as they passed. But that was different. Those women were locals. The landlord’s taped women were white, and Pea couldn’t say why, but the videos were to him somehow a violation.

“Is it your cousin?” Pea asked. “You staying up to watch TV with him?”

“There’s a job he wants me to take. It’s good money.”

Pea swallowed. He pulled the calendar page from his pocket. “You promised thirty days.” He circled the number with his finger. “I can take care of us.”

“It’s not enough, though, is it? It’s not enough to live in this city.”

“It will be. See how fast this place is changing?”

He took Nam’s bowl from her and stacked it over his empty one. “If you’re just going to waste this, I’ll eat it. Look, just give me time with the job. Who knows what kind of work that cousin wants to find you.”

“I know,” she said.

“Except you don’t. You don’t understand.” His job was a beginning for them, and he wanted her to see that it was good.

That night he brought her to the flower market.

“Hey!” Pea gestured over to his coworker. “This is my girlfriend.”

Nam was distant; she wouldn’t enter the warehouse.

“I don’t know.” She held his arm but pulled away. “I’ll get you in trouble.”

“I’m not even on duty yet. Look at these.” They were flanked by the red eyes of a hundred roses. “Just buds, see, but soon they’ll bloom.” He pulled one free of its newspaper bunch. “Here. For you! Oh, watch the thorns, ha ha!”

“Are these from China?”

“I think so. Take it home. Or take a whole bunch for your cousin. Here—”

“No, don’t waste the money.”

“It’s free. Don’t worry. The boss likes me and he lets me take things home. These will wilt soon, anyway. And then they’ll just throw them away. Isn’t that funny? They come all this way just to live a few days.”

Every morning that week, returning from the warehouse at sunrise, Pea brought Nam stolen flowers. Like a bird adding strips of cotton, foam, twigs, and newspaper to a nest, Pea made his best effort to construct their new life.

Every morning he counted his pay and turned the number in his head, waiting for Nam’s cousin to leave for work. The man didn’t know about Pea. The cousin was unmarried, but the young maid Nam shared the back room with was loyal, and she reported everything back to him.

The next day Pea brought the maid an attar of roses to perfume her clothes. She liked that, this maid who didn’t seem to work but spent her days reclined on her bunk. She was gone most nights.

“A boyfriend?” Pea had asked Nam once, but she didn’t say.

Pea cut the noses from plastic soda bottles to make suitable vases for his gifts: hibiscus, gardenia, a jasmine wreath. “Aren’t they beautiful?” he asked, and the maid said yes, beautiful. Nam said nothing. She picked at the Pepsi label.

Didn’t she like them?

“I think it’s romantic,” the maid said.

Nam let the plants accumulate and then decay, as if to prove a point. What point, though? Soon the bedroom was looking like a carnival, twisted creatures crusting across the dresser, curling on shelves and, in the warped and cracked mirror, multiplying into a kaleidoscope of faded, darkened color. The vase water thickened awfully. The room was behind the kitchen, and in the heat the scent invaded the cooking area, infusing the food. The steam rising from the rice cooker had the fragrance of decayed vanilla orchids, and the smell of old needle flowers clung to the dishware like a dank nectar.

Nam’s cousin complained. But Pea did not need to be told to stop. By the end of the week, on their twenty-second day in Bangkok, he was out of work.

So, Pea, what have you done now? Nam would say. It’s your attitude, she would tell him.

“That boy’s temper,” the elders back home had bemoaned again and again. “He’d better grow out of it.” The temple’s older foster boys had even tried to beat it out of him.

“How about we fill that big mouth of yours.” They scooped manure from the mounds of fertilizer and came after him.

Or they would pin him at the shower bucket and take turns holding him under, saying, “All you have to do is cry ‘Bingo!’ Got, it? What’s that? Want us to stop? Bingo!” Pea writhed and coughed, but never pleaded. One night they came at him while he toyed with his new cigarette lighter, an American Zippo. Before they could grab his wrists, Pea used the hot metal to brand a boy’s cheek.

“Who the fuck does that?” They backed away.

“Bingo,” Pea said.

The head monk laughed when he heard about it. “Too much Die Hard.”

The monk beat the boy but let him keep the lighter. Pea had seen the wrong lesson in his prize: fight.

THE OTHER MEN were asleep when Pea returned to the shared room the night he lost his job. He drummed his fingers on the water kettle, thirsty, wanting a clean drink now.

His inky fingerprints seemed to collect everywhere these days. Blue on the bathroom tap, blue on the hem of his shirt. An absent stain on his lip. When one boarder complained, Pea held himself back from marring that man’s face, too. Now he had marked the kettle.

The apartment window faced a narrow soi where the dawn vendors were already setting up. Below, a woman was preparing the first batch of fried dough, and the sound of the batter striking the hot oil carried up to Pea, reminding him of eating at the stalls back home. Why had he even come to this city?

The foreman’s words echoed in his head. “I don’t think we have room for you, after all.” He said he didn’t need a boy who couldn’t keep his mouth shut. There were others waiting for work, still coming off the trains and buses, brought in by the drought. But Pea hadn’t come because of the drought; he’d come for Nam.

He hadn’t hesitated in following her to the city after her father, her only immediate family, had died. Both Pea and Nam came from small families. A house was never meant to be held up by a single pillar, and when Nam’s father died, everything had quickly come down.

He went to find her, walking by way of a fresh market. It wasn’t quite dawn. Men were unloading the day’s produce: fish in green baskets that leaked over the sidewalk, sagging pork already being sliced for the first customers. He bought a bag of soy milk and approached the flower vendor.

“You have any old stuff?” he asked.

The woman didn’t seem to understand him. He often had to repeat himself with these Bangkok people, their bland way of speaking utterly unlike his own.

“Anything? Any scraps?”

She didn’t.

“Well, how about this bunch?” He gestured to a small display of flowers. “These are local, right?” Not that he could afford them. When he said it was his aunt’s funeral, that he wouldn’t show up empty-handed, she relented and gave him a pair of lilies.

Pea was on the sidewalk of Nam’s soi, deciding whether to sneak up to her room, when he saw the maid stumble off a bus. She braced a hand on the shophouse’s curtained gate as she removed her heels with two violent kicks.

“Hey.” He touched her shoulder.

“Shit!” She stepped back against the gate, her shock rattling the metal. “Pea? Scared me there. The fuck. Coming at me out of the dark like that?”

Pea didn’t speak. The maid’s dress was short and black, the bottom crumpled and flaring unevenly. She looked down and flattened the fabric against her thighs.

“So, uh, you waiting for Nam?”

“You’re dressed like a whore,” he said plainly. “Is this how your boyfriend likes to see you?”

She blinked for a moment. Then she raised her hand and, with her pinkie, carefully edged back her eyelashes.

“Right.” She bent to loop her wrist through her heel straps before turning to the padlock on the gate. The dress revealed her back all the way down to the dimples of her spine. Pea brushed his knuckles down the naked skin.

The maid hesitated with the key. She turned to face him. “I’ll tell her you’re out here, but you can’t wait in front of the shophouse.”

He knew already what Nam’s reaction would be: What have you done, Pea?

“No. Here, take this.” The nodding lilies. “Tell her I was here with the flowers. Tell her I’m working a double shift.”

HE MISSED THE open country. Back home you could see where you were going. Here, the city led the way, forcing turns onto streets flanked by, it seemed, the same shophouses he had already passed. Every pawn shop was built like a prison and every gold store had paid a policeman to stand nearby. Inside, the gold chains seemed to cascade from the walls where they hung. He asked about security guard jobs. He was a good worker. He even knew some English, and said as much to a travel agency hiring a receptionist. They laughed, though, when he demonstrated; they said country boys can’t even speak Thai properly. Said he had a way of standing too close. Back up.

That was his problem with the whole city. It was too close to see all of it. He wanted to reach out and grasp it, just . . . hold it still for a moment.

A Chinese neighborhood. The buildings wore the familiar wooden shutters he hadn’t seen much here in Bangkok. Another way the city wasn’t quite right. He tried to think about perspective, think like a city person, what the monks back home had drilled into him through countless iterations of their precious few lessons. Pea remembered the routine: a monk would improvise with recent headlines, saying, “What accounts for those ten-wheelers colliding head-to-head on the Khon Kaen ring road? Lack of perspective.”

“I hear it’s because the drivers are all on ya ba,” some smart-ass would say from the back. “And then when they come down they fall asleep at the wheel.”

Ignoring the boy, the monk would walk the novices to a window looking out to the rows of rubber trees behind the old dorm. The four glass squares made a neat grid, except each pane was warped.

A question that was actually a statement: “Which pane shows us reality.”

Surely, there was a moral to this. After the others had been absorbed back into their temple duties, Pea returned to the window. He brought his eye to each pane, trying to divine an answer for himself.

Eventually he took to skipping the temple’s homegrown education. He searched out his own learning by walking. He told himself stories. Spy games, war tales, Chinese epics. He looked with envy into shop fronts and found his mood mirrored in the faces of idle servers, barbers who, like him, could do nothing but wait.

When Nam returned from school, Pea would meet her at her house. She often shared her notes from school, but he grew impatient, frustrated by his own stalled education. And so he always interrupted her.

“But you wouldn’t believe what I’ve seen today,” he’d say.

And when she said, “What’ve you seen, Pea?” he would tell her his stories, invite her to visit his otherworld.

Their favorite place that he’d discovered was the swimming pool. It was the only finished structure in a sports club that had been recently abandoned. The pool was deep and bare, tiled over in a winking blue. They climbed down the ladder and dropped into the deep end. When the rainy season came the pool would be lost to them, turned forever into a reservoir, making its welcoming, dry depths more precious now.

Sitting against the pool wall in the late afternoon, they were shaded to their ankles, all the way to Nam’s modest school socks that were folded over three times. Always three—Pea had watched her don them.

They played a game. Nam made the rules, but never seemed to follow them herself. They threw stones and removed clothes. It never went further, though, than Pea’s underwear and Nam’s skirt, which was fine. It was her naked back he coveted—the slight contortion of her shoulder blades as she pulled off her blouse.

Afterwards, as they dressed, Nam would count the items of clothing removed. “Five.”

And when he took her home, they sometimes stopped to a buy a lottery ticket. “Something ending in five,” she advised.

PEA PAUSED TO scan the lottery tickets on a street-side vendor’s tray, but he didn’t like the numbers. He walked through boys playing soccer on a side soi, kicking the ball off cars to complete their passes. He cataloged everything he saw so as to try and convey these impressions to Nam, over dinner, as he made his usual assessment of the food.

“Old fish paste, crumbly rice, clumped sugar. Everything’s a little off. It’s the whole city.” They were in a shophouse near her cousin’s house. Pea laid down his spoon with finality and washed his mouth out. “And the water tastes like salt.” He held the cup out to her.

“You’re imagining it.”

He sucked his lips. “Yup, salt.”

“I didn’t see you this morning,” she said.

The day was over and he still hadn’t found work. “Yeah, they had me take an extra shift.”

“Wait, let me pay this time,” Nam said. “I have the money.”

“Money from where?”

“My cousin gave it to me.”

He turned away while the vendor made change.

“Why’s he giving you money?”

“I helped clean the upstairs.” She had spread her fried rice across the plate. Now she ran her spoon through it, turning it up like turf.

“You’re not a maid. I hope your cousin knows.” Pea grasped her hand, stilling the spoon’s progress. “Okay? You’re not a maid.”

She put down the spoon and clasped his hand.

He cupped her cheek in his other palm and she leaned into it. Then he ran his thumb in a line beneath her eye, inadvertently pulling the skin and making her flinch. His nail came away shaded with charcoal.

“Who asked you to put makeup on?”

She jerked back. “Stop.”

“You stop. I saw the maid this morning, all dolled up.”

She dipped a napkin into her glass and wiped the color from her eyes. She folded over the stain, then wiped again with a clean side.

“It’s nothing. I’m just trying it out.”

“Don’t lie to me.”

Nam looked directly at him, the charcoal around her eyes smudged.

“I can’t talk to you when you’re like this.” She rose from the table and dropped the napkin into her glass.

He didn’t follow her, but remained where he was, watching the paper napkin bloom in the water.

A MONSOON WAS rolling in from the Philippines. In the corner-store TV the storm was a red wound over the belly of the globe. At least it would break the heat that had the migrants churning—nobody at the apartment was getting sleep.

“And this new porn actually has a story,” one of them was saying as Pea returned. “Which is somehow even worse. All talk.”

“Where’ve you been, kid?” another said to Pea.

“Don’t touch me.” Pea shrugged off the man’s hand. He felt surrounded. The apartment was like a mousetrap.

“Hey! That’s all right. It’s no problem.”

“Hush now.” Two of the men were huddled outside the landlord’s door. “Kid, you came back for the right night. Quiet now or we’ll miss it.”

Pea went to stand over them. “What is it?” He heard the woman’s throaty, steady gasps, a repetitive smacking.

He was about to retreat when the sound suddenly cut as the speakers exploded into the national anthem, a swelling chorus of singers, a sound that returned the boarders to boyhoods spent lined up on the cracked concrete of schoolyards. It returned them to schoolboy grins and a muffled laughter that broke their cluster, had them shaking as the TV was abruptly switched off.

One man held Pea by the shoulder, barely holding back his laughter. “I recorded over the tape this morning. How about that? You’ll sleep tonight, huh? Now don’t tell me we don’t take care of one another.”

It was this man who sent Pea, the following evening, in the direction of a job.

“Old man Gui’s generous,” Pea was told. “He’s been helping kids a long time.”

The man turned out to be a fried-chicken vendor, work-worn, his body chewed to the bone. His shirt was unbuttoned, and whatever weak substance a tattooist had used on the man’s chest had gone faint now, appearing gangrenous, like a sickness laying its roots in the man’s ribs.

“I’m looking for work.”

Seeming to recognize Pea as one of his own, an Isaan boy, the man perched on the motorbike attached to his cart. Pea could smell the chicken that was spitting in the deep fryer.

“You and everyone else who came in from the country.” The man lifted a drumstick from his tray and offered it to Pea. “Go on.”

It was still hot. The rich oil filled Pea’s mouth, but the texture was wrong.

“Mix the rice flour with baking soda to lighten it up. It’ll make it crispier.”

The man studied Pea. “You think so?”

“And your cuts?” Pea turned the drumstick to display the gouges. “They’re too deep. The meat loses its bite.”

The man held out a bag for the bone. “How long you been here?”

Pea swallowed and unfolded his calendar page. The oil from his finger made a clear circle of the number. “Twenty-five days.”

“You look sturdy enough.”

The man said Pea could work as a night guard. He led Pea to the warehouse where he would keep watch over street carts, which at day’s end were wheeled in by the vendors.

“You line the carts facing that wall, in rows. Morning carts go in last. The vendors will tell you.”

“Doesn’t seem that hard.”

“It’s not,” the old man snapped. “You think people want to steal food carts? You’re here in case it floods when the rain finally comes. It’s happened before, so don’t wander.”

Midday sun cut into the space through a hole in the ceiling as Pea walked along the wall.

“What is this place?”

“A movie theater. Can’t you see that?”

The room was all decay. Termites had chewed through everything, even the sound insulation. Pea ran his nail up the laced wood, imagining he could hear it, the insects’ crunching, the sound of a city feeding upon itself.

“But what happened to it?”

“It closed.” The man looked at Pea closely. “Can’t you see that?”

“Must’ve been sad when it happened.”

“This isn’t the only one. If you don’t find a way in this city, you’re gone. Doesn’t matter if you’re rich, either. I’ve seen rich go poor.” He led Pea back up the ramp. “You find them everywhere. Those dancing clubs. Some of them barely opened a year. Now? A parking lot. Soon, a mall. Or McDonald’s. That man’s buying everywhere.”

WHEN PEA RANG the bell this time it was Nam’s cousin who approached. Pea realized he had never called on her in the evening. He had come to tell her about the job.

The cousin was tall and thick with shoe-polish-black hair. Even his eyebrows seemed to have been unnaturally inked. He parted the metal gate.

“Who are you?”

“I’m looking for Nam.”

“And what do you want with her?”

“Just to talk to her.” Pea looked beyond the man.

“She left already. She’s working.”

“Working where?”

“And who are you?” Her cousin came forward now, filling the opening he had made. He stood over Pea, the padlock heavy in his fist. “Hey? You looking for trouble?”

Before the cousin could advance again, Pea shoved him back against the gate, which slid aside as the man tried to catch himself but fell to the ground. Pea came forward, putting his weight on the man’s wrist. He felt it crack underfoot.

Pea took the padlock and hefted it. He considered its weight.

Pea stepped back, releasing the spongy wrist. He slid shut the gate but kept hold of the padlock, never looking away from the man now cradling his arm.

THE DRINK CARTS were the heaviest, the jangling bottles of syrup all stocked full, making a deadweight of this thing on wheels. When he lost his grip on the ramp, Pea nearly ran himself over. The men he worked with were polite but weary. When they finished their work they didn’t linger, and soon Pea was alone. Wasn’t this what he’d wanted?

Only now that he was alone, the question was unavoidable: Was Nam’s cousin lying about her working? Pea was afraid he might not be. Finished with the cigarette he had salvaged from a food cart, he drifted off to sleep thinking about those four windowpanes from his boyhood, and the glass-warped trees beyond them.

He woke with his fingers still clipped around the cigarette stub, from which emanated a sticky, black dread. It was finally raining outside. He could hear it on the roof of the theater and there was a dark puddle at the entrance. But that wasn’t what woke him.

Nam looked stark under the one fluorescent tube he had on, a bulb webbed to a cart by its own wires.

“Your roommates sent me here.”

He pictured her at the apartment, the clustered migrants, a woman’s moan looping behind the landlord’s bedroom door.

Nam could read him. “They were polite.”

“This is where I work now.” He felt the need to explain this, but she walked away from him to the back where some seats were still bolted to the floor in ranks. She let her fingers brush the brass number on one of the arms.

Pea stood up and followed her, pointing up at the movie posters high on the walls. “These are actually hand-painted.”

“Battle of the Bulge,” Nam read. “Cleopatra. I can’t make out this name, though. Doctor . . .” She trailed off.

She looked at him again. “The rivers are so low, my cousin told me, the seawater’s backing up into the delta, into the pipes. That’s why the hose water is salty. They’re using it to wash dishes and cups. You were right,” she said. “I know that’s important to you.”

“Your cousin . . .”

“His wrist is broken.”

Pea sat down again. “You know why.”

“What do I know?”

“What work has he forced you into?”

She moved to stand before him. She took his face in her hands, gingerly, as if laying her palms on a hot surface, and turned his chin up to her.

“What work?” she asked.

“You know.”

“You won’t even say it. So how can I try and talk to you about it? And it wasn’t my cousin, either. He doesn’t even know. It’s his maid.”

The maid’s naked back. Her dress. Pea remained silent. Then he pulled out his calendar page.

Nam took it from him. “I can take care of us, Pea. Okay? I can do this.”

She laid his head against her chest then. He clutched her, fingers plucking unconsciously at her blouse, then working the back zipper down an inch. “The old, swimming pool days,” he said. “Remember? I want to go back.”

Pea hadn’t acknowledged this to himself until he heard his own voice speak the words. It sounded weak, and when Nam didn’t respond he wanted to reclaim them. But what could he tell her in their place? He had prepared his stories.

“You know what I’ve seen today . . .” he began.

“What’ve you seen, Pea?”

His first aerial view of Bangkok from a futsal pitch on a dormitory roof. The owner of the herbal remedies store doing lunges behind her store counter. A bleached-blond woman on a bicycle, hair lit up by oncoming headlights.

He couldn’t tell her. He knew she had prepared her story, too, and didn’t want her to tell him yet. So he stared up at a movie poster. A woman in gold reclined between two men.

“Tell me about this film,” he said. “What’s it about?”

She saw what he couldn’t.

“Power.”

What You Bargained For

RICK, NAM & PEA (1980)

Women are meant to be Thai. That’s what your buddy Phil told you before you flew over from the States and became the man you’d sworn you’d never be, sitting at this bar with a woman—no, a girl—you want to describe as a flower. Not because she’s pretty—she isn’t really—but because of the way she leans toward you with an open face as painted up as a false rose, glistening under a sheen of moisture, a red mouth widening in a way that reminds you of what’s between her legs.

“Her” being your wife. You haven’t slept with anyone but Mary since you were seventeen. Twenty-five years. That’s fidelity, you told yourself during the divorce last year, when you were peeking down the shirt of your daughter’s friend as the girls did push-ups in the garage. Her breasts hung down in points. You toyed with the idea of them over you, over your lips.

“Juicy,” Phil says on your left, eyeing a girl in a green Heineken minidress.

“Steaks are juicy, Phil. Not people.”

Phil puts a hand on your shoulder and kneads his thumb into your collarbone.

“Rick, look where we are. Why’d we come to Bangkok?”

He’s right. This is exactly what you came for. This bar-lined street. Its drinking holes extending right out onto the sidewalk, so that you’re sharing your space with passing motorbikes and drunks stumbling in the gutter. A fluorescent palm blazes above you. The metal stool between your legs scrapes the pavement as you shift, and you keep shifting because Nam—the flower beside you, now fingering the ice in her drink—has her knees pressed into your leg. Is this what you came here for? You notice the splotches beneath her eyes. She looks up at you and smiles.

“That’s what you came for,” Phil coaxes with a grin. “My friend here’s a little quiet,” he tells Nam. He takes her hand and slaps it down on your leg. “So you’ll have to do the talking, sweetheart, khao chai? It’s his first night.”

But this is all it takes—just this. A year from now, at your wedding, Phil will drunkenly recount this night. “So there’s our damsel, Rick, getting his lights punched out by some Thai kid when this beauty here steps in to save him. She even taught him to dance. I remember the moves. Awful,” he’ll say, resurrecting your heel-shuffling for the wedding reception. You’ll insist on the church, even though those God-granted bonds hardly held for your first marriage.

“You like dancing?” Nam’s hand is still planted on your leg.

“I can’t. You’d laugh.”

“Like him?” She indicates a man larger than you who is keeling from side to side like a rowboat. Nam mimics his gait on her barstool, rocking her head between her shoulders. She laughs. “Come on, dance with me.”

You shake your head, make excuses. You say you don’t even know the tune—something thumping out of Nam’s generation. Christ, Rick, she’s nineteen. Your daughter’s age. That’s if she’s telling you the truth. And nobody’s telling you the truth. Not your daughter, Sam, who had known about the other man, and certainly not your wife. What did you expect? That’s what Mary told you—“What did you expect?”—when you found the condom floating in the toilet, pink and still slimy in your fingers when, in your shock, you picked it up. Not my dick, you thought, sizing up your competition. Had she put it on for him, you wondered.

“You like Bangkok?” Nam says.

What do you even know about Bangkok? So far, you’ve seen the inside of a mall and this street. You’re jet-lagged. It’s morning on the East Coast, completely and utterly the wrong time to be out. You pick up Nam’s hand and lay it gently on the bar.

“Is this where you’re from?” You make a twirling motion with your finger. “Well, not here, this street, but, you know, Bangkok?”

Nam smiles.

Try again. “Bangkok. Are you from Bangkok?”

“No,” she says. “My home in Udon Thani.”

“Right.” Though, where is that? You’ve heard of Phuket, the beach you’re headed to next week. You turn to Phil, but he’s trying to explain the plot of some movie to the girl in his lap—“And he’s a real slugger, know what I mean?”—so instead you sip your whiskey.

Nam takes your hand. Unexpected. Raises it like you’re about to make a vow.

“Bangkok,” she says, pressing her finger into the meat of your palm, somewhere near the bottom where hand joins wrist. “In Thai called Krung Thep.”

You repeat this.

She traces her finger up the palm, racing northeast, across the callused expanse from your rowing days. You’re ticklish. The skin flinches. She moves up the pinkie of your splayed fingers.

“Udon Thani. My home.” She pinches the finger at its tip.

“How about Phuket? I’m going next week.”

Back down the length of the country, through Bangkok, south, southwest, onto your wrist, lower, tracing the blue rivers below the skin. She stops halfway down your forearm.

“Koh Phuket. Island.” She looks at you. Coyly, “I go with you?”

Swell idea. Or . . . not. Reclaim your hand.

“Maybe.” You’re drunk. “My daughter’s your age, you know.”

“What her name?”

“Nineteen this year. Samantha.”

Nam tilts her head. “If I go America, I be friend with Samantha?”

God, no.

Nam puts your hand on her bare knee. Her legs have these tiny hairs, and when your hand moves against them it feels like someone’s breathing on your palm. When was the last time you touched something that smooth? Mary’s belly? At eighteen maybe, and in the last months of her pregnancy with Sam, the taut flesh like a great tent roof.

Beneath the skin, you think you can sense Nam’s pulse. You’re remembering what Mr. Jobson told you back in high school biology, about where you can feel the body’s beat: wrist, neck, elbow crook, the fold behind the knee, the warm place between the legs. So you start touching with your fingers, not a stroke, softer, the way you used to touch Sam in her crib after she’d screamed herself to sleep, laying two fingers across the cushion of her cheek, a curl of spit drying around your fingertips.

You always saw more of Mary in Sam—Mary’s boxy teeth, the way she slept with an eye peeking open, a white crescent that watched you through the night. She’s got Mary’s rolling temper, too. You were reminded of that last Christmas when she shut the front door on you, as if the divorce had been your fault. She didn’t even take the present—an Arthur Conan Doyle collection from your childhood along with a tuition check, so she could reenroll at college—which was the only reason you were even there. You certainly hadn’t planned to stay. Of course not. Just far enough into the foyer to see the tree all lit. You hesitated, thinking how stupid it was to knock on what was, after all, your own door.

Your hand has stopped at the hem of Nam’s skirt. You’re poised to go farther, to breach the door, but also to take your hand back, heft the Christmas gift under your arm and return to the car. You teeter on the brink.

Nam scoots forward until you’re under her skirt without even trying.

Oh.

She picks up her glass and takes the straw in her mouth.

“You like Thai woman?” Her knees squeeze together, pinching your wrist, an encouragement to get closer. Go on. Her knee against your arm. You think about those knees around your back. Young, strong, embracing your waist. The tendons tight against your side. You’ll feel those legs tonight, in your hotel room, when you’ll also discover that she’s never had sex.

In your head: What kind of bar girl—no, never mind. How will you know? Not the blood—she was forced to pop that herself, as she’ll tell you much later, squatting in a black toilet reaching up inside. It’ll be her eyes: afraid of you. It will make you think about your size, the swell of your stomach looming over her like a pale moon.

You’ll recall the first time with Mary, and how afterwards you sat on the car hood watching the moon rise, the soft pink glow on the ocean’s horizon ballooning in your memory. Mary was right beside you, sitting up against the car windshield wearing your t-shirt. Your jeans piled on boots nearby, and, farther off, your belt, in the bush where Mary had tossed it. Her body stretched into the view: the dimpled muscle of her legs, the gloss on her toenails. You fell in love with her languid confidence, the sense that she was strutting even while just lying still. That evening, it had been enough to make you come out with some stale line about her, the sun, you in orbit. Only, Mary shook her head. “No, nothing so cosmic,” she said. “We could be anybody, really.”

When you remember this you’ll stop. Your knees will sink into the hotel bed. You’ll stare at Nam’s dark face below you, like a stain on the sheets. Her curry sweat. The slight sour between her legs. What are you doing? You’ll say it aloud, to yourself; only, Nam will think it’s her. She’ll blink, then apologize. She’ll shift beneath you and fold her legs so you slip out. She’ll hide her face from you.

“I’M SORRY.” You slip off your barstool. You’re going back to the hotel. To the States.

Nam stands, too. She’s worried. She looks over her shoulder.

“Please.” She catches your hand. “Where you go?”

“Home.”

You see Phil dancing inside the bar. He’s laughing, lifting a girl against his chest as if he means to make off with her, dance her into the horizon for the fairy-tale finish that you have twice been promised. Once by your wife on the day you were married, and again by Phil when he invited you out here.

“Why Bangkok?” you had asked when you met up to celebrate the divorce.

“Life is cheap. We could live like kings.”

But it was too far from Sam.

“Oh, you love your fucking women so much,” Phil said. “Look, you want women? We’ll find you some.”

And that’s what Phil’s found, all right, that girl with her swollen look, like bleeding fruit heavy on its branch. Phil saw Sam only once, a couple of years after she was born. “Kids are anchors, you know? Around your feet. You’re up here right now,” he said, drawing a line at his neck, “but for the rest of your life you can expect to sink.” You and Mary laughed about it afterwards. You never invited him back to the house, only meeting him out at bars every couple weeks.

“I just keep him around to remind me what I would be without you,” you told Mary, when she asked why you wasted time on that creep.

Phil’s still dancing. He doesn’t hear you shout his name.

“Why you go?” Nam asks. On her feet she’s smaller. The dress loosens around her, pulls at her shoulders so that she looks like one of those Japanese cartoon characters made up of all lengths and no girth.

“Stay with me.”

You know it’s a production-line comment, just another gear in the works of what these girls are taught. It’s also what you said to Mary after you found the condom. Unlike your wife, you’ve never had the conviction to walk away.

You sit back down, making sure there’s an entire barstool between the two of you. And maybe it’s worked. She’s lost that confident veneer, that pin-on twinkle.

“A year ago my wife found another man,” you say as Nam pours your drink. “Right in time for our big anniversary, too, you know? Twenty-five years. Can you believe it? Empires have crumbled in less.”

“Yes,” Nam says.

“Enough time to pay off a goddamn mortgage. And what do I have to show for it?” You empty the glass. “A lying, college dropout of a daughter.” You wave away at the air in front of Nam. “No, actually, that’s not fair. It’s not Sam’s fault. I was the one who told her if she moved in with her mom I’d cut her college funding. So then she left school. Look how that turned out.”

Nam’s eyes are fixed on your extended hand.

“You don’t even understand me, do you?”

In a small voice: “I understand.”

“No you don’t.”

You have to stretch across the empty seat between you. A jagged kiss. Half lip, half cheek. Their mouths are so damn small, these Thai women.

Their hips, too, thankfully. You’ll always be able to wrap Nam’s waist in the crook of your arm. Not like Mary. One Thanksgiving you made a joke about Mary easing off the pumpkin pie. “You all should have seen the woman I actually married. I mean, wow.”

Mary had turned to the table with that bizarre smile of hers—teeth that didn’t meet, more like a grimace. She gave a small laugh as if to say, What can you do?

“Jesus, Dad,” Sam said. “Why do you have to be such an asshole?”

That Thanksgiving night, as Mary changed by the bed, you pressed your chest into her back and bunched her stomach in your fist.

“Some things that stretch don’t go back,” Mary said, referring to the difficulties she had with Sam’s birth. You told her that she wasn’t being fair, that it was a joke.

“That’s the thing, Rick.” She unclasped your hand and stepped out of reach, but red fingerprints clung to her rumpled skin. “You’re always making jokes.”

YOUR MOUTH IS still on Nam when it comes: the cheap shot, the punch that knocks you out of your seat. At first you think you’ve just slipped off your stool. That the ground itself gave in. But no, you realize, palm against the thumping of your temple. You stare up at the Thai boy who has punched you. Young, Nam’s age. His eyes are bloated and red. Teeth clenched. Teeth that you can smell, suddenly, as he throws his weight on you and jams an arm under your chin, forcing you back to the ground. Another strike to your ear, which you hear now as though you’re under water, a muted ring dulling all sound. You fumble at his face. But he’s out of reach, in Nam’s arms. She’s facing the boy, blocking him. And he won’t touch her.

Phil steps around Nam and takes an elbow to the boy’s head. He follows with a heel when the boy curls onto the ground. “Huy, huy, huy,” some Thai men are yelling, pulling Phil away. Two of them lead the boy across the street. Nam follows them.

You stare across the street. A yellow sign for Teen Love Massage Parlor winks at you. The bar girls lean in. Alive? their faces seem to say. Awake? They twitter in Thai. One’s in a cowboy hat. Another in tassels and a bra. You tell them you’re not really hurt. You lift yourself onto your elbows.

“Fuckin’ junkie kids,” Phil says.