Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Seren

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

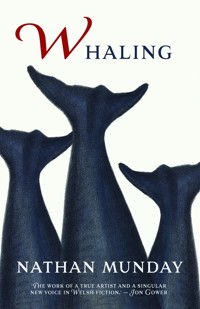

1792. Nantucket whalers are invited to found the port of Milford Haven in Wales. What does the arrival of these hardy Quakers – immigrants to America a century before – mean for the local people? And what is the meaning of the beached whale that preceded them? Two cultures rub against each other and distrust grows, driven by the local preacher. As Whaling unfolds concern swerves into hysteria against the incomers and the preacher plans a grotesque, Jonah-inspired fate for the whalers. Nathan Munday's debut novel is an exciting mélange of original fiction, historical writing and whaling images. In it he explores our relationship with the natural world, the boundary between faith and superstition, and the age old problem of immigration. Set in historical fact this is a narrative at once modern and contemporaneous, the writing rich in imagery and deceptively tense as its story slides into allegory.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 227

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

WHALING

For Jenna

Seren is the book imprint of

Poetry Wales Press Ltd.

Suite 6, 4 Derwen Road, Bridgend, Wales, CF31 1LH

www.serenbooks.com

facebook.com/SerenBooks

twitter@SerenBooks

The right of Nathan Munday to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

© Nathan Munday, 2023

ISBN: 9781781727065

Ebook: 9781781727072

A CIP record for this title is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted at any time or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the copyright holder.

The publisher acknowledges the financial assistance of the Books Council of Wales.

Printed in Plantin by Akcent Media Ltd

Whaling

, φάλαινα, Balaena mysticetus, Hvalur, Morfil, Míol mór, Megaptera novaeangliae, Balaenoptera musculus, Eschrichtius robustus, Sandlægja, Balea, Bálna, Baleine, Hran, Hronfixas, Bellua, Wal, Walvis, Walfisk, Whale…

Milford Haven, Wales

In 1792, fifteen Nantucket whale men and their families moved to Milford Haven, Wales, where they operated a branch of the whale fishery. They were encouraged by Sir William Hamilton of Linlithgow (1730-1803) and Sir Charles Francis Greville (1749-1809).1

1 A small card on one of the walls of Nantucket Whaling Museum (c. 2016). The note fails to mention the curious incident faithfully recorded in this book.

PART I

‘There is no isolated sin’ – Fyodor Dostoevsky

She dives again. The depth clamps the vessel as it churns through the sea; it’s propelled by a giant hand, waving goodbye to every patch of blue and black. The lights from the overworld are minimal – just the big orb looming. She swims for a while before surfacing. It feels cold and unnatural. She lifts her tail with ease, waiting for the last drops of water to skitter off her oily skin before crashing down, deep dive – swerving into the dark.

A whole world lies on her back: water-hitchhikers. Small fish too tired to swim. Crabs, crustaceans, mussels, and bits of weed ribboning on the moving reef. Her eyes are tired, but the plankton is good. Dots. Dots. Dots. Pixelating pieces of weed. Dots. Dots. More dots glowing like stars. Unlike the other fish, she has seen the real night sky when surfacing for air. She imagines other seas above the earth where rocky vessels rotate around these special lamps. She dives again.

She remembers swimming in the waters off America. She remembers looking towards the land and seeing a giant deity flinging his moccasin over the blue. The titan had too much sand in his shoe and in frustration he hurled it, with the sand, and a whole chunk of earth into the deep. Nantucket was born.

The whale dives again and dreams about the shallow waters near Madaket where her ancestors went to die. They slowly glided on the sand and stopped where the scallops closed.

Sometimes she hits bits. Pieces of wood, rubbish. To her, they are just passing obstacles dropped out of the pockets of the world. She tanks through, ignoring them or pushing them aside with her nose.

Suddenly something falls from above. It is silver and looks like an argent shooting star in the higher seas. It comes towards her. Closer. Closer. It leaves a trail of bubbles fast. She can’t avoid it.

red

It’s in her. The water is warming… red

red

She dives and gets away.

“Blast it! Argh!” He shouts. He sniffs. He squats. He gets up.

A spectacled young harpooner, Joseph, returns to the deck of the Sierra Leone with glittering eyes. Saliva whitens the corners of his mouth, water drips from his breeches. He pulls them up before untying the chafing cord from around his waist. Joseph shivers. Joseph is aware that he is the best. Joseph is an artist of great talent.

“Curses!”

A murmur runs through the men. The rhythmic sea-chop calms as Joseph reluctantly takes breath. The boat follows suit, groaning a dirge, then creaking in the deep. Its arthritic hull remembering warmer currents; its wood wooing the weed, catching it, holding it, and seducing it to stay on its body. The smaller Yankee whaleboats, still laden with men, bump against the large ship like herring.

“I lost her,” his words comb the wind.

His ears buzzing. Another rope is hauled up — a wetter and heavier rope — before a large, silver harpoon crashes onto the deck like an oversized crucifix extracted from the deep. Then another one. Blood comes, recalling the creature, slowly dispersing its scarlet hue on to the salt-soaked bark.

A woman cautiously approaches and hands Jo a beaker of water.

“You well Jo?” She asks.

“Aye, aye. I’m fine woman. I lost another one.”

Her hands are as dirty as his. Her thin form turns sideways, disappearing into the rigging without a word. Jo drinks and watches the life-stream as it leaves the harpoon before settling on the Sierra Leone.

The speed of the fish was otherworldly. Its presence manifested itself like a tolling bell on the crispest morning. Jo heard the fountain shooting, the shouting, and the sudden fear that descended like glory on the anaemic men that shepherded the sea. Yes, they were sore afraid when the presence made itself known. They knew what was necessary but, for Jo, the sacrifice was overwhelming. He knew that the boats would topple for a chance of a better life, or that the seas claimed their flesh, from time to time, in payment for taking such a noble prize. This time, the whale survived.

The Dart Extracted from Mr Melville’s Moby Dick

“Show me his arms then. Ha! No, no. Too thin. Way too thin! Not nearly big enough to strike the first iron. The harpooner is stronger. Listen, you must understand that he’s peacemaker and warrior; he’s this strange fusion of artist and killer, creator and destroyer. He’s hard, yes. Give him good, strong arms. These things matter. Where was I?”

“The dart.”

“Yes, the dart. Forgive me, I should clarify. The dart, that sharp harpoon, that heavy thing needs to be flung twenty or thirty feet. The chase can be a long affair. Your harpooner needs to pull the oars, throw this weight, and set an example. Sounds easy – does it not – but on the open water, ‘tis no small thing, especially the latter. That physical excursion is powered by loud and intrepid exclamations. Grunts. Shouting his tonsils sore, he’ll keep ’em going. Aye. In this straining, rowing, bawling state, then, with his back to the fish, they’ll cry – Stand up, and give it to him! He drops the oar. Turns around on the chop. Seizes his harpoon from the crotch and, extracting a strength from somewhere, lunges it towards the whale. They say that five out of fifty are successful. If that. No wonder so many harpooners are marred with curse-gaze, frustrated and distant; no wonder some of them shed sweat drops of blood; and no wonder some of them wander for years looking for the single spurt. The harpooner must be the best. The harpooner must be an artist of great talent.”

“Herman?”

“Yes?”

“The crotch? I don’t understand.”

“The crotch deserves independent mention. It is a notched stick, some two feet in length, which is perpendicularly inserted into the starboard gunwale near the bow, for the purpose of furnishing a rest for the harpoon, whose other naked, barbed end projects from the prow. Thereby the weapon is instantly at hand to its hurler, who snatches it up as readily from its rest. It is customary to have two harpoons reposing in the crotch, respectively called the first and second irons. These two harpoons, each by its own cord, are both connected with the line; the object being this: to dart them both, if possible, one instantly after the other into the same whale; so that if, in the coming drag, one should draw out, the other may still retain a hold. It is a doubling of the chances. But it very often happens that owing to the instantaneous, violent, convulsive running of the whale upon receiving the first iron, it becomes impossible for the harpooneer, however lightning-like in his movements, to pitch the second iron into him. Nevertheless, as the second iron is already connected with the line, and the line is running, hence that weapon must, at all events, be anticipatingly tossed out of the boat, somehow and somewhere; else the most terrible jeopardy would involve all hands! Listen to me, you must understand that when the second iron is thrown overboard, it becomes a dangling, sharp-edged terror, skittishly curvetting about both boat and whale, entangling the lines, or cutting them, and making a prodigious sensation in all directions.”

“Can it be retrieved?” He scribbles in his pad with a shrinking pencil.

The older man shakes his head, “Impossible. Impossible. Not until the whale is fairly captured and a corpse.”

William John Huggins, ‘Harmony’ (1829)

Too right, I wept.

I couldn’t help it.

Those cracking bones

circling my mind like crows.

The scene reddening – its garment soaking-up

the spilt offering plugged by some

flagpole.

I’d name them,

undie them, if I could,

but no poem resurrects or

wipes away.

I pray for stopped boats and

snapped harpoons,

and the pricked consciences of their owners.

We’ll face those birds one day,

and explain why such dissonance

characterized our watch.

Too right, I wept.

I couldn’t stop it

“Sh…sh…she’s wounded then?”

A wiry youngster pours a bucket of sea over Jo’s feet. A simple man. He, too, is thin. If he had long hair, there’s no doubt it would be employed to patter the spray. His alabaster bottle is a black bucket. Instead, he anoints his hero with words, stammering words, twitching on the deck-floor like the movements of a passing mackerel.

Andrew Pewter does not belong to the seven privileged clans but to one of the eight unfortunate families. Whaling involves a salty class. Top-hatted captain class ruling like chiefs and under-sailors as their loyal subjects. Difficult to break into.

“Yes, unfortunately.”

Jo sips from the beaker, his teeth tingling from the chase. He bites down on the lip, waiting for that weakness to pass.

“What’ll happen?”

“She’ll probably die, Andrew.” Beaker plonks on deck. He wipes brown blood from his lenses. Many times, he’s thought of abandoning his spectacles and allowing the sea and all its trimmings to fuse into one mass of blue and black.

“S, s, sorry boss.”

Andrew skulks away; his curling hair giving him that Caesar look while his eyes reflect the mad philosophers, broken from over-thinking. He mulls over the creature and its pain, driving him into the corner where he breaks bread and counts the seconds it takes for the blood to fill each cavity, gap, and fibre of the bobbing mass. Andrew knows he’ll never hold a harpoon. No, he’s a small fish attaching himself to the bigger swimmers as they cascade through the waters. Andrew’s gaze moves towards the decks. The stench of each kill broods in his nostrils adding a degree of organicity to this man-made vessel. Sailors soon forget that the beams were crafted by their own kind, the sails sewn by their women, and the prayers uttered by their brothers. The tall men turn into mangroves, the short men are the bowing roots, cluttering the scene, swimming in the half-light of wet and dry.

Jo takes off his glasses, wiping them clean again. He begins drawing with his mind:

The Town of Sherburne in the Island of Nantucket (c.1775) Mr Starbuck Senior and Mr Folger can be seen pushing a boat into the sea in their youth. The third person is unknown to the author.

Sherburne’s dreams are all baleen.

That white-etched, saline touch,

never dissipating.

Hot sands weave memories into stories,

and scrimshaw is scratched from the seas.

Its waters clustered with translations,

cluttered with chowder cartons

slowly emptying their content

into

the

bay.

Milky hues break the shore,

clam to clam – not dust – but ground shell, sparkling like

gemstones in the flow.

This materia, these deposits, regurgitate further tales

laden with shoals of

ichthyic signs.

Nantucket sound — blue sand and yellow water — an epoch away. Every time Jo closes his eyes, the blue and yellow fold into one another like dough kneaded by his mother’s hands. He recalls his own softer, vacant hands, not laden with irons or kneaded by salt, but marinated with the memory of clam chowder. His palms warming themselves around white-blue bowls. Fingers stained with cranberries. The palette of the past is diluted with that same chowder — cloudy and fishy — seasoned with that same feeling of dread that accompanies the final dregs of a delicious stew. Once his fingers are warm enough, and the colours return like birds, he begins to see the fences: white teeth, perfectly lined in front of the houses. Windmills rotating like fish tails on the horizon, light then dark, light, and dark… and the meeting house defiantly facing the sea. The lighthouse is up again, and the gyres of its innards are re-constructed — step by step.

He walked with her on Surfside Beach. Eyelash grass blinked in the wind as faintest greens shimmered between silver and gold — an alchemy initiated by her fingers. The stretched-out sand like strips of ribbon, pulled tightly by the island’s grip. She looked around and took off her jacket, her bonnet, and her stockings.

“What on earth are you doing, woman?” She laughed at him. Each note, beautiful.

“Come on. Nobody’s here!” She kept her undergarments on. The moccasins protected her feet from the scorching sands. Her dilated pupils pearled her eyes in umber, carob, and hickory, capturing the sea in their reservoirs. An ancient Nantucketer returned, bright-eyed and brave. Jo soon followed. His clothing fused with skin and cracking shells pinched his soles. Eventually, she gave up those moccasins and threw them towards him.

“Watch it!”

The water lapped against their bellies. They held their clothing down, fighting the ludic current. She bent her knees, entering an oily mass like a white penitent, covering her breasts carefully with her palms – ever looking, fearing the eyes of the island. She walked…

…into the deep. The navy. Her island floated like a mountain – diamantine, upside down – rotating on an unseen surface. She stretched her hands into the void, her mother’s ring glistening like a star on a ghostly edifice. The remaining clothing streaming behind like jellyfish. She followed the line of the island with her finger before looking down.

Soft shapes.

Distant spectres.

Moving voodoo dolls,

pinned

with

harp-

oo-

n

s.

Breathless with awe at their appearance.

They re-surfaced.

“Jo!” she pants.

“What?”

“Whales. I can see whales in the distance!”

“Is that right?” he said. “Don’t be daft. ’Tis far too close to shore.”

“Seriously! Look!”

“Don’t be silly, darling.” Pulling his curtain fringe from his eyes.

He saw nothing, and it annoyed him. This moment conjured green in the deep heart’s core. The water begged him not to think it. But, with a sudden urge, he disturbed that sacred communion:

“We should be going … this ain’t proper… come, now,” he said. And with that, the garden was gone forever.

The historian K.D. McKay introduces us to Nantucket, one of the main characters in this novel, in A Grand Design: The History of Milford, Part One 1790-1809

Nantucket with its shire town of Sherborn, developed in the eighteenth century not only as a leading colonial port but also as a great whaling centre and the home of the then new Southern Whale Fishery. The way in which this new industry developed was dominated by the Nantucket Quakers, who were, in many ways, a new breed of The Society of Friends. The affects of their beliefs spread well beyond religion and embraced the conduct of social and commercial affairs.

During the American War of Independence, the Quakers, in keeping with their beliefs, managed to keep the island of Nantucket as a ‘neutral enclave’. They also maintained their community as a cohesive whole – if dissident factions did appear, they did not become too troublesome. They achieved this because of unrelenting efforts which enabled them to come to satisfactory arrangements with both the Royal Navy and the American Continental Congress. These arrangements, or understandings, allowed them to continue with some whaling during the war and hence keep their hopes alive.

However, their hopes were soon to be dashed when the war ended. Splits began to appear in their ranks – Loyalists who had supported England quarrelled with the Continental Faction whose views were more in keeping with the aspirations of the emerging United States. Nevertheless, whaling on a large scale was resumed, candles were made, oil was refined; but a lucrative market could not be found for these products because of confusion over the precise status of Nantucket.

Charles Skinner remembers Nantucket’s Early Days and suggests a different Genesis in his Myths and Legends of our Own Land (1896)

There is no such place as Martha’s Vineyard, except in geography and common speech. It is Martin Wyngaard’s Island, and so was named by Skipper Block, an Albany Dutchman. But they would English his name, even in his own town, for it lingers there in Vineyard Point. Bartholomew Gosnold was one of the first white visitors here, for he landed in 1602, and lived on the island for a time, collecting a cargo of sassafras and returning thence to England because he feared the savages.

This scarred and windy spot was the home of the Indian giant, Maushope, who could wade across the sound to the mainland without wetting his knees, though he once started to build a causeway from Gay Head to Cuttyhunk and had laid the rocks where you may now see them, when a crab bit his toe and he gave up the work in disgust. He lived on whales, mostly, and broiled his dinners on fires made at Devil’s Den from trees that he tore up by the roots like weeds. In his tempers he raised mists to perplex sea-wanderers, and for sport he would show lights on Gay Head, though these may have been only the fires he made to cook his supper with, and of which some beds of lignite are to be found as remains. He clove No-Man’s Land from Gay Head, turned his children into fish, and when his wife objected he flung her to Seconnet Point, where she preyed on all who passed before she hardened into a ledge.

It is reported that he found the island by following a bird that had been stealing children from Cape Cod, as they rolled in the warm sand or paddled on the edge of the sea. He waded after this winged robber until he reached Martha’s Vineyard, where he found the bones of all the children that had been stolen. Tired with his hunt he sat down to fill his pipe; but as there was no tobacco, he plucked some tons of poke that grew thickly, and that Indians sometimes used as a substitute for the fragrant weed. His pipe being filled and lighted, its fumes rolled over the ocean like a mist—in fact, the Indians would say, when a fog was rising, Here comes old Maushope’s smoke—and when he finished he emptied his pipe into the sea. Falling on a shallow, the ashes made the island of Nantucket. The first Indians to reach the latter place were the parents of a babe that had been stolen by an eagle. They followed the bird in their canoe, but arrived too late, for the little bones had been picked clean. The Norsemen rediscovered the island and called it Naukiton.

The pain in her side is worse than calf-birth. Her mouth opens. The power that bore her abandons her in a salt mist only an ocean can conjure. Even the hangers-on flee with her unorthodox movements. There is no soothing hand or poultice to press her wound except the continual drive of movement. She’s never seen her own body; one picture on one side, and another distinct picture on the other, while all between is nothingness.

She forms her own landscape. One eye resembles a distant lake on the side of a great mountain. A crater. Her head towering from that lake like a blunt cliff before dropping into another lake on the opposite side. Her back is a ridgeway: another crib in the water’s vista; an archipelago when surfacing, and a spit when swimming away from land. On one side, she observes the passing sea like a horizontal waterfall; on the other side, she watches its passing like another fall. In earlier years, she saw others swimming by her side. But now,

she’s alone.

The sea is cracking. Old Lir stretches his worn-out back, tired-out from being. He begs her to notice the currents, weaving each wave between her polished body. The depth has never felt so deep before, its tapestry of woe wearing her down.

Tilting her body sideways, she looks down with her eye, scanning for a sign.

Nothing.

The giant hand remains vigilant — a heartbeat machine — up and down like a hurried goodbye.

She remembers another flash in the upper sea when a man disturbed their world. A great storm drawn to his limbs; thunder had never been seen underwater before. An irresistible magnetism drew her towards that rattler, darting through the high currents like a burning space stone. The other fish stayed away as the figure swayed in agony, writhing as he fell.

That’s when she swallowed him.

She wonders whether she’s wandered into those strange waters again. Manically, she tuna-swims towards any hint of difference. The sparkling plankton has lost its hue.

She longs for home and the cauldron of morning.

The sea is cracking.

She feels alone.

Arctic whaling in the eighteenth century. The ships are Dutch, and the animals depicted are Bowhead Whales. Beerenburg on Jan Mayen Land can be seen in the background.

A bowhead poised for planting

a tricolour harpoon.

Red. White. And Blue.

Come now, Jan, let’s colonise

for the land has its backbone.

Break it!

The main hill is the head.

Climb it!

The sun-eye shines like silver

for our taking.

A Beginner’s Guide to Whaling according to Mr Stubb recorded in Mr Melville’s ‘Moby Dick’.

“Pull up — pull up!” he cried to the bowsman as the whale finally relaxed. The spray-breath giant-like, blowing and blowing. Stubb leant over the boat, stretched himself, churning his long sharp lance into the fish, and kept it there, carefully churning and churning, as if cautiously seeking to retrieve some gold watch that the whale might have swallowed. But that gold watch he sought was the soul of the fish — its innermost life. From what they call the trance the fish entered the flurry, a bloody stage. It wallows in its own blood, wrapping itself in crimson spray of frenzy.

And now abating in his flurry, the whale once more rolled out into view; surging from side to side; spasmodically dilating and contracting his spout-hole, with sharp, cracking, agonized respirations. At last, gush after gush of clotted red gore, as if it had been the purple lees of Bordeaux, shot into the frighted air; and falling back again, ran dripping down his motionless flanks into the sea. His heart had burst!

“He’s dead, Mr. Stubb,” said Daggoo.

“Yes, both pipes smoked out!” and withdrawing his own from his mouth, Stubb scattered the dead ashes over the water; and, for a moment, stood thoughtfully eyeing the vast corpse he had made.

She feels alone, but continues to swim…

Land or mirage? After weeks onboard the Sierra Leone, Jo senses the approaching weight plein-air, Antwerp blue. He can’t see it yet, but only on the desert sea can you crave dry oases.

Idle. Same breakfast. Same malnourished ginger cat mewing from a lack of mouse. Every day, the same sound seeping into their existence. The same water and the same people scowling at petty grievances.

A moon hangs in the sky like a lantern, ready to uncover a genesis. His eyes adjust to the present before making out distant dots — notes of life — lurking like brooding animals.

View of the harbour of Milford Haven by George Attwood. Fleet assembled may be carrying reinforcements to the American War of Independence or they may be showing the arrival of the families on the Sierra Leone.

The hamlet of Hakin Hubberston is visible, which would form the nucleus of the later town of Milford Haven. National Museum of Wales.

“Land ahoy boys!” Jo yells. “Land!”

Excitement erupts. Men blowing snot from their nostrils before grabbing the nearest rope. The hulk is steered towards Jo’s finger, and the reluctant bell with its wind-caused ding, is eerier when others, beyond the boat, may hear its single sound. The hills and eddying valley-fog engulfs them, shapes, and scales unknown. Jo turns for a moment and eyes the paper pinned to the mast, flapping in the breeze:

21st of February 1791.

Compensation for the voyage. Removal Expenses. £1000 worth of timber and stone. Easy accommodation, Protection and Preference… a peppercorn rent for the Site of a Meeting House and Burying Ground and exemption from all Ground Rents for 2 years from Midsummer. It is promised that the new settlers will not embarrass themselves with agriculture but depend on the markets which the richness of the country can supply to any degree of increased population. Lands may be rented in the neighbourhood for 7 or 14 years from 18 to 30 shillings an acre according to their quality and more distant situations cheaper.

Charles Francis Greville

Charles Francis Greville. Port-creator. Art-collector. A powerful man. His curlicued signature flicking through paper like waves, crashing against their minds with promises.

He needed the best oil harvesters. Yes, they were the best. He’d heard that these same Quakers are the most sanguinary of all sailors and whale-hunters. They are fighting Quakers; they are Quakers with a vengeance. Just like his paintings — the best — the Nantucket families are a worthy addition to any collection. Forget sugar and slaves, this was real business, squeaky clean: lubricated with spermaceti. Divine sparks.