Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Iron Press

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

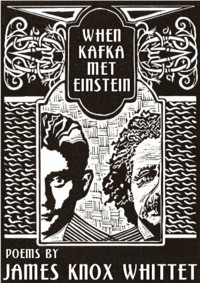

When Kafka Met Einstein is the first full collection from Scottish poet James Knox Whittet. The poems combine the playful and the intellectual, moving easily between Nietzsche and the Teletubbies. Brought up on the island of Islay, some of Knox Whittet's poetry is inspired by the landscapes and history of Scottish islands, while elsewhere he is at Newport Pagnell Service Station at 3am, or writing about Iris Murdoch's Alzheimer's. There is also a poem about the little-known fact that Hitler attended the same school as Wittgenstein. This book is also available as an ebook: buy it from Amazon here. James Knox Whittet was born and brought up on the Hebridean island of Islay, where his father was head gardener at a small castle. His poems have won the George Crabbe Memorial Award three times. His first poetry pamphlet, A Brief History Of Devotion, was published by Hawthorn Press in 2003; his second, Seven Poems for Engraved Fishermen, was shortlisted for the Callum MacDonald Award from the National Library of Scotland (2004). He has previously edited two acclaimed anthologies for Iron Press: 100 Island Poems of Great Britain and Ireland (2005) and Writers on Islands (2008); the latter was nominated by the Scotsman as one of the Books of the Year. He now lives in Norfolk.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 68

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Poems

James Knox Whittet

Foreword

Pauline Stainer

First published 2012 (print and ebook) by IRON Press 5 Marden Terrace Cullercoats North Shields NE30 4PD

tel/fax +44(0)191 2531901 [email protected] www.ironpress.co.uk

ISBN 978-0-9565725-6-1

© James Knox Whittet 2012

Cover artwork by Mandy Tait

IRON Press Books are distributed by Central Books and represented by Inpress Ltd, Churchill House, 12 Mosley Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE1 1DE

Tel: 44(0) 191 230 8104

The Poems

When Kafka Met Einstein

Transmutability

A Brief History of Devotion

In Memory of R. S. Thomas

Cuttings

Imprints

Echoes

Lawrence of Arabia in Collieston

Moving with the Times

The Last Man on Jura

The Comma Butterfly

Peaches

Dante in Auschwitz

Fires of Memory

Hands

Infinite Wheels

Virginia Woolf on Skye

Circles of Fire

Borrowed Words

Aisles

3 a.m. at Newport Pagnell Service Station

Sea Winds

New Wine in an Old Tea Urn

Patterns of Carpets

From the Tractatus to Teletubbyland

Hebridean Haiku

One Jewish Boy

The Descent

Torch

Carousel of Silences

Globed Lamp

Tongues of Flame

Late Night Phone-In

The Destined Journey of Etty Hillesum

Folds

After Dark

Terminus

Spells

The Lives and Deaths of St. Kilda

A Lift

Finding the Darkness

The Biscuit Barrel

Island Incident

Fragments of Eden

Laundered Towels

Tea Dance on a Tuesday Afternoon

Languages of Babyle

The Resurrection of Gilbert Kaplan

Absence

Einstein in Cromer

Biography

James Knox Whittet was born and brought up in the Hebridean Island of Islay where his father was head gardener at Dunlossit Castle. His paternal grandmother came from a crofting family on the Isle of Skye. James was educated at Keills Primary in Islay, Newbattle Abbey College and Cambridge University. His pamphlet, A Brief History Of Devotion (The Hawthorn Press) was published in 2003. In 2004, his pamphlet, Seven Poems for Engraved Fishermen (Meniscus Press) was shortlisted for the Callum MacDonald Award from the National Library of Scotland.

In the same year, he received an award from the Society of Authors. He edited the anthology 100 Island Poems (IRON Press), published in 2005 which was nominated by The Scotsman as one of the Books of the Year and received a major award from the Arts Council of England. He also edited the companion volume, Writers On Islands (IRON Press), published in 2008. James won the George Crabbe Memorial Award in 2004, 2005, 2008 and 2011. In 2009, he won the Neil Gunn Memorial Award for poetry and an award from Highland Arts. In 2010 his translation of Sorley MacLean’s Hallaig was commended in The Times Stephen Spender Prize. The spoken word CD of his poems entitled Dark Islands was released in 2011. This is his first full poetry collection.

To Ann

Foreword

This is a quietly amazing collection of poetry. It moves full circle from Kafka’s meeting with Einstein to a final poem about Einstein in Cromer. Its eclectic range includes Wittgenstein as a presiding spirit in Connemara, Dante in Auschwitz and Virginia Woolf on Skye. There are memories of an island childhood, landscapes, seascapes, lost traditions. The poems unfold with great patience in a variety of verse form and breadth of line. Everything, unusually, is given time.

James Knox Whittet’s Islay background may account for this. Anyone who has heard him read his poems, will have been struck by their incantatory quality. Each island is its own kingdom, shot through with skerry and lighthouse, the rustle of light on water. Fields are still scythed, oats stand in stooks. Crofters’ ghosts rise from the lazybeds. The lives and deaths of St. Kilda are probed with great subtlety by the poet. For the dead still listen and wait.

The observation in these poems is sharply sensuous. The dipping of ‘varnished oars into peated water’, ‘green and silver bands of mackerel’, the ‘burnt honey scent of gorse’. An island childhood is suffused with salt and peat smoke, the furling and unfurling of descended swans, the way anchored lilies whiten a loch. Particularly brilliant is the treatment of light, its behaviour between remote isles, the exchange between lucidity and reflection. Detail is meticulous in all the poems. Kafka’s father is caught slumped asleep, his forehead imprinted with ‘washable ink’ from the unread newspaper.

The vitality of poetry stems partly from wonderful oppositions. James Knox Whittet’s sestina for Wittgenstein in Connemara and his poem Virginia Woolf on Skye are examples of such crossings. They allow the writer release from his island background, and spring from the tension between outgoing and holding back. The poet can throw glimmering tangents, as well as evoke ‘daylight’s undersides’. These glimpses, at a remove so to speak, give the writer freedom from his awareness of being alone in the crowd.

In these many-layered poems, one complexity hatches another. A retarded child’s experience of abuse by a priest is suggested obliquely through borrowed words. In the magnificent Peaches, memory momentarily transfigures a hospice. Fruit are plucked again by the dying with infinite tenderness. Each peach folded in tissue with its downy cleavage, boxed and left on chilled marble in the castle pantry. All this caught delicately under the merciful bewilderment of diamorphine.

James Knox Whittet writes with deep compassion. Those slow and biblical ‘silences of God’ which were part of an islander’s way of being, sustain his writing. Etty Hillesum still walks with her lost children in the luminously unfenced fields of peppery lupins.

Pauline Stainer

When Kafka Met Einstein

When Kafka Met Einstein

You listened with your wolf-like ears,

in background, as always, while he

harangued his devotees with bewildering

concepts of space and time and motion.

You were no stranger to bewilderment:

alone at night in your room, gazing down

on the ant-like citizens of Prague who

scurried along labyrinthine corridors of

streets, with the mythical figure of your

father ensconced below you in a deep armchair,

like a throne: asleep, his forehead imprinted

with washable ink from the unread newspaper.

In the womb of this room, you gestated

the alien bodies of your lovers: Felice, Julie, Milena . . .

exploring them and yourself in indelible letter

after letter, bridging chasms with the mathematical

constructs of your imperturbable sentences.

Here too, you dreamed of Gregor Samsa:

a man of obsessive, mechanical habits who,

like yourself, spent his leisure hours on

imaginary journeys through railway timetables,

and who awoke to find that his body had

rebelled against him in the dark, leaving him

shamefully unable to catch his regular train to work.

Like Einstein, you transformed our conception

of the world by dreaming of the motions

of trains which accelerated to the speed of

light and you waved your bloodied handkerchief

to rows of absolutes left standing on the platform.

Between 1910 and 1912, Franz Kafka frequently met Albert Einstein at a salon in Prague. Einstein’s study of train schedules and train motion had a profound influence on the development of the theory of relativity.

Transmutability

Last night I dreamed about you … all I know is that we kept merging into each other … but here too the uncertainty of transmutability entered.– Kafka in a letter to Milena.

In the cut-glass of evening with the animal city

kept at bay behind panes and smothering curtains,

I caress the insubstantial dream of your body with my pen.

Father, my judge and silent confessor, sits monumentally

in the room below me as I magnify myself with

ink at this heavy desk: supported on his shoulders.

Each letter I form is a needle which penetrates my

flesh like the tooth of a harrow until recognition

incinerates my eyes when each sentence is complete.

I wound myself so that you might enter and our

insect limbs become so entangled that I no longer

know where you end and I begin as I journey through

corridors which lead nowhere and everywhere to stand,

at last, in front of one who will inform me of my crime.

A Brief History of Devotion

For then we should know the mind of God.– Stephen Hawking

They pack auditoriums to hear you,

worshippers of the loose-limbed oracle

whose electric voice reverberates

through those vast interstices where God hides.