Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Birlinn

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

William McGonagall was born in Edinburgh in 1830. His father was a poor hand-loom weaver, and his work took his family to Glasgow, then to Dundee. William attended school for eighteen months before the age of seven, and received no further formal education. Later, as a mill worker, he used to read books in the evening, taking great interest in Shakespeare's plays. In 1877, McGonagall suddenly discovered himself 'to be a poet'. Since then, thousands of people the world over have enjoyed the verse of Scotland's alternative national poet. This volume brings together the three famous collections – Poetic Gems, More Poetic Gems and Last Poetic Gems, and also includes an introduction by Chris Hunt, the webmaster of the McGonagall website www.mcgonagall-online.org.uk, indexes of poem titles and first lines, and features the first publication of McGonagall's only play, Jack o' the Cudgel, written in 1886 but not performed publicly until 2002.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 747

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

William McGonagall

Collected Poems

This ebook edition published in 2011 by Birlinn Limited West Newington House Newington Road Edinburgh EH9 1QSwww.birlinn.co.uk

First published in 2011 by Birlinn Ltd

Introduction and note on Jack o’ the Cudgel Chris Hunt, 2006

The moral right of Alistair Moffat and James F. Wilson to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

ebook ISBN: 978-0-85790-073-9

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

CONTENTS

Introduction

POETIC GEMS

MORE POETIC GEMS

LAST POETIC GEMS

JACK O’ THE CUDGELor The Hero of a Hundred Fights

Index of first lines

Index of poem titles

INTRODUCTION

William McGonagall’s early life is shrouded in an uncertainty largely of his own making. The accounts he left us of his childhood contradict both each other and the few official records in which his name appears. He was probably born in 1825, the son of Irish immigrants Charles and Margaret McGonagall. An early census record gives his place of birth as Ireland, but the poet always claimed to have been born in Edinburgh. Be that as it may, the McGonagall family led a transitory existence, stopping in Maybole, Edinburgh and Glasgow before finally settling in the west end of Dundee. During this time, young William received perhaps a year’s formal schooling. Once established in Dundee, William was soon apprenticed to follow the trade of his father, that of a hand-loom weaver.

In 1846, he married Jean King and the young couple set up home together, starting a family that would eventually number five sons and two daughters. This appears to have been a relatively prosperous period in McGonagall’s life. Although weaving was a job increasingly performed by machines, there were still jobs of a complexity that called for the skills of a weaver, and as a skilled worker McGonagall could command higher wages and status.

His evenings were spent reading, and he developed a particular liking for the works of Shakespeare, committing to memory the parts of Richard III, Hamlet, Othello and Macbeth. It was in this latter role that he made his first stage appearance, and gave us the first glimpse, perhaps, of what was to come. A local theatrical impresario was persuaded, having received a substantial advance payment raised by McGonagall’s workmates, to allow him to take the part of Macbeth for a night in a professional production. Encouraged by the applause from an audience packed with his friends, McGonagall was convinced that his fellow cast members were envious of his success. When the final fight scene reached its climax, an exasperated Macduff was quite unable to get the Scottish king to die, and was eventually soundly beaten himself! McGonagall was carried in triumph from the theatre, having given Shakespeare’s tragedy a new ending. Scenes from Macbeth would remain a key part of his repertoire in later years, but would usually be played solo!

And so McGonagall’s life progressed for many years, working, reading and entertaining friends. He was fast becoming a pillar of conventional Victorian respectability: a family man, a devout churchgoer and an ardent supporter of the temperance movement.

The 1870s must have been a stressful time in the McGonagall household. Weaving work was becoming harder to find and Margaret, William’s oldest daughter, brought shame on the family by giving birth to an illegitimate son, who joined the rest of the seven children squeezed into the family home. Out of this chaos, perhaps even because of it, came the turning point in McGonagall’s life:

The most startling incident in my life was the time I discovered myself to be a poet, which was in the year 1877 [ . . . ] I seemed to feel as it were a strange kind of feeling stealing over me, and remained so for about five minutes. A flame, as Lord Byron has said, seemed to kindle up my entire frame, along with a strong desire to write poetry; and I felt so happy, so happy, that I was inclined to dance, then I began to pace backwards and forwards in the room, trying to shake off all thought of writing poetry; but the more I tried, the more strong the sensation became. It was so strong, I imagined that a pen was in my right hand, and a voice crying, “Write! Write!”

A poem was quickly penned in praise of local preacher George Gilfillan and delivered to a local newspaper. It must have been a slow news day, for the effort was duly published and McGonagall’s career as a poet had begun. More works followed fast: an ode to Shakespeare and one to Burns being early examples. McGonagall soon realised that, like many great artists, he would need a patron to support him while he wrote. Never one to do things by half measures, McGonagall went straight to the top: a letter seeking royal support was dispatched to Queen Victoria herself.

A lesser man might have found her response – a polite thankyou letter from a royal functionary – disappointing. William, however, took this in his stride. If he had been thanked for a written collection of his works, how much more might he gain from a live performance? The queen was staying just fifty miles away in Balmoral Castle; he would walk through the mountains to see her.

Alas, it was not to be. In what would become a pattern in McGonagall’s career, he made the whole trip only to fall at the last hurdle, which in this case was a sergeant at the gate of the castle who observed, “You’re not the queen’s poet! Lord Tennyson is the queen’s poet!” and sent him packing back to Dundee.

It still gave him a story to tell the local papers, and he followed it up with poems on a wide range of subjects: local beauty spots, famous people, historical events, news stories at home – all could inspire a new poem. The newly penned ode would be printed onto broadsheets and McGonagall would tread the streets of Dundee selling them. In the evenings, when possible, he would secure a venue in which to give a live performance. Word soon spread about the poet’s abilities, and audiences would turn up with rotten food and other missiles, ready to show their appreciation. If this reception discouraged McGonagall, he never showed it. No praise was too faint for him to latch onto as proof of his powers, whilst any critics were given short shrift. McGonagall himself described one such incident in a piece he wrote (in the third person) for the Dundee People’s Journal entitled “Poet McGonagall’s Tour Through Fife”. During a trip to Dunfermline in 1879,

[h]e called upon the Worthy Chief Templar who received him in a very unchristian manner, by telling him he could not assist him, and besides telling William his poetry was very bad; so William told him it was so very bad that Her Majesty had thanked him for what he had condemned, and left him, telling him at the same time he was an enemy and he would report him.

Soon he was styling himself as Dundee’s official poet and attempting to take part in whatever ceremonies and parades might take place. He was rarely successful, but could still write a poem about the event and sell a few copies on the street. When not performing in Dundee, he would tour the local neighbourhood, doing shows for bemused villagers or visiting larger towns at the behest of some local literary group in search of fun.

In 1880 he boarded a ship for London, seeking to make his fortune in what was then the biggest city in the world. Sadly, no theatre would have him and, as performing on the street was beneath his dignity, he was back in Dundee within the week. Seven years later he embarked on an even greater adventure, crossing the Atlantic to try his luck in New York. Alas, he was no more successful over there and was soon on the boat back to Scotland.

Back home he secured a regular spot in a local circus, declaiming his verse as best he could to a crowd well-armed with eggs, flour, herrings, potatoes and stale bread. By now over sixty years of age, McGonagall would withstand this barrage for the princely sum of fifteen shillings a night. However, these riotous affairs attracted the attention of the city’s magistrates who placed a ban on further performances. It was a bitter blow to McGonagall. In response, he wrote:

Fellow citizens of Bonnie Dundee

Are ye aware how the magistrates have treated me?

Nay, do not stare or make a fuss

When I tell ye they have boycotted me from appearing in Royal Circus,

Which in my opinion is a great shame,

And a dishonour to the city’s name.

He added a few highlights from his poetic oeuvre:

Who was’t that immortalised the old and the new railway bridges of the Silvery Tay?

Also the inauguration of the Hill of Balgay?

Likewise the Silvery Tay rolling on its way?

And the Newport Railway?

Besides the Dundee Volunteers?

Which met with their approbation and hearty cheers.

And has it come to this in Bonnie Dundee?

The magistrates remained unmoved, and William sloped off to Glasgow to attempt to ply his trade there. Once again he failed to thrive, and was back home after a month, although something good was about to come from his misfortune. In April 1890, his friends rallied round and organised the publication of a slender volume of Poetic Gems, selected from the works of Mr William McGonagall, with biographical sketch by the author, and portrait. Two hundred copies were sold immediately, and a copy inscribed by the author was lodged in Dundee’s Free Library.

Book sales and more broadsheets allowed him just enough money to live, but appeals to the home secretary to overturn the magistrates’ ban fell on deaf ears, as did one for a pension paid from the civil list and backed by the signatures of hundreds of Dundee citizens. Sadly, not all Dundonians were so supportive and his continuing mistreatment in the city’s streets caused him, in 1893, to write an angry verse, threatening to leave the city. One newspaper archly observed, “When he discovers the full value of the circumstance that Dundee rhymes with 1893, he may be induced to reconsider his decision and stay for yet a year.”

So it proved, with McGonagall finding new ways to earn a crust. He was an early pioneer of the celebrity endorsement. For a few lines in praise of a local tweed manufacturer, he was given a new suit of the stuff. Next, he tried his hand at advertising, singing the praises of Beecham’s Pills and Sunlight Soap, the latter earning him the sum of two guineas. It wasn’t enough though, and in October 1894 he and his wife finally took leave of a city that had been their home for over fifty years.

At first he moved just twenty miles up the Tay valley to Perth, a town where he had always received a good reception. While there, he was sent an extraordinary package purporting to have come from the court of King Theebaw of Burma. Contained within were a small silver elephant and a letter conferring upon him a knighthood in the Burmese Order of the White Elephant. It was a hoax of course, but if McGonagall saw through it, he wasn’t letting on. To the end of his days he remained Sir William Topaz McGonagall, Knight of the White Elephant, Burmah.

His time in Perth seems to have been relatively peaceful, although he found it harder to sell enough poems to this smaller population. Still, it was a base from whence he could travel to Glasgow, Inverness and Edinburgh to give his performances. Whilst doing a show in the Scottish capital, he was visited by Henry Irving and Ellen Terry and was reported to have received his fellow tragedians graciously.

In 1895 he left Perth and moved to Edinburgh. The period that followed was the most successful one of his career. He became a cult figure amongst the students of the capital and was in much demand for entertainments. Even if they were laughing at him behind his back, at least they weren’t throwing anything at him – a great improvement over Dundee.

However, such fashions do not last for ever, and as the twentieth century dawned he was once again in desperate straits. Now nearly eighty years of age and troubled by deafness and bronchitis, he was no longer able to tramp the streets selling his works. Donations from friends kept the wolf from the door, but he was embarking on the last chapter in his life.

His writing continued unabated, motivated as ever by the news of the day. Queen Victoria’s death in January 1901 inspired a “gem”, which was followed by an address to her successor Edward VII. The coronation, which took place in August 1902, was the seed for another poem (now lost); it was to be his last. He died of a cerebral haemorrhage on 29 September 1902 and was buried in an unmarked grave.

*

McGonagall’s choice of subject matter was a lot wider than he is often given credit for. His best known poem (at least to modern audiences) commemorates a railway disaster, and he has a reputation for concentrating on such subjects. In fact his range of subject matter was a lot greater. He wrote of local beauty spots and other places, of famous people and of current events – particularly the battles constantly being fought to maintain Queen Victoria’s empire. Disaster poems made up barely 10 per cent of his output.

One subject area, however, is conspicuously absent from his work – he rarely wrote anything that touches upon his own feelings for those around him. We have a few poems commemorating particular poetic performances or announcing his intention to leave Dundee, but there is nothing addressed to his wife or to his children.

If McGonagall’s poetic works tell us nothing of his personal life, the same cannot be said of his autobiographical writings. In many ways they resemble the Grossmiths’ Diary of a Nobody, and by reading between the lines we can see how the world saw McGonagall as well as how he saw himself. He shared many of the faults of Mr Pooter, being pompous, self-important, humourless and the butt of jokes he didn’t understand.

From the day divine inspiration to write poetry descended upon McGonagall, he was addicted to rhyme and the same rhyme pairs would often appear in his writing – if a poem involved the queen, she’d be somewhere “green” or “wondrous to be seen”. If there was an uplifting story to be told, it would be engraved in letters of gold. Even when McGonagall was supposed to be writing prose, the rhyming demon sometimes got the better of him:

[There was] a merry shake of hands all round, which made the dockyard loudly resound. Then when the handshakings were o’er the steam whistle began to roar. Then the engine started, and the steamer left the shore, while she sailed smoothly o’er the waters of the Tay, and the passengers’ hearts felt light and gay.

Although rhyming was a compulsion with McGonagall, scansion was completely alien to him. The long rambling lines, ending with that vital rhyme, are the most recognisable feature of his work and sometimes reach prodigious proportions:

On one occasion King James the Fifth of Scotland, when alone, in disguise,

Near by the Bridge of Cramond met with rather a disagreeable surprise.

The third element in McGonagall’s poetic technique – or lack of it – is his extraordinary ability to puncture whatever pathos he may have been able to create by the addition of some extraneous fact or an inappropriate phrase, as here in the “Albion Battleship Calamity”:

Her Majesty has sent a message of sympathy to the bereaved ones in distress,

And the Duke and Duchess of York have sent 25 guineas I must confess.

And £1,000 from the Directors of the Thames Ironworks and Shipbuilding Company,

Which I hope will help to fill the bereaved ones’ hearts with glee.

Was McGonagall really that bad, or was he deliberately writing that way for comic effect? It’s a question that his contemporaries posed, and it is still asked today. Was he, as some writers suggest, a satirist – deliberately sending up the views that he was purporting to espouse?

The satirist argument is difficult to sustain. It is based on extracts like this, from “The Funeral of the Late Ex-Provost Rough”:

And when the good man’s health began to decline

The doctor ordered him to take each day two glasses of wine,

But he soon saw the evil of it, and from it he shrunk,

The noble old patriarch, for fear of getting drunk.

And although the doctor advised him to continue taking the wine,

Still the hero of the temperance cause did decline,

And told the doctor he wouldn’t of wine take any more,

So in a short time his spirit fled to heaven, where all troubles are o’er.

Is McGonagall making fun of the rather too enthusiastic temperance supporter, or is the comic effect an unintentional by-product of his own zeal from the cause? If such cases were common, we might have cause to wonder, but McGonagall wrote literally hundreds of poems with no possible satirical intent. Why would he waste time writing “Beautiful Balmerino” or “Forget-Me-Not” if satire was his aim?

If not a satirist, was he a comedian, a poetic version of Tommy Cooper? This too seems unlikely for several reasons. Firstly, and most importantly, he was so unsuccessful. Apart from a brief period in Edinburgh, his writing never yielded him any serious money or recognition. If he wasn’t making a decent living from his “art”, why persist with it?

Secondly, if his poems are read with care, his technique can be seen to improve somewhat over the years. If we look at an early work like “The Railway Bridge of the Silvery Tay” (written in 1878), we see a series of stanzas of irregular length, with as many rhymes thrown into each one as he can think of:

Beautiful Railway Bridge of the Silvery Tay!

With your numerous arches and pillars in so grand array

And your central girders, which seem to the eye

To be almost towering to the sky.

The greatest wonder of the day,

And a great beautification to the River Tay,

Most beautiful to be seen,

Nearby Dundee and the Magdalen Green.

Beautiful Railway Bridge of the Silvery Tay!

That has caused the Emperor of Brazil to leave

His home far away, incognito in his dress,

And view thee ere he passed along en route to Inverness.

If we compare this with a later work, such as “The Storming of the Dargai Heights” (written in 1897), we see that he has adopted a regular four-line stanza and an AABB rhyme scheme, although his characteristic disregard for scansion remains:

’Twas on the 20th of November, and in the year of 1897,

That the cheers of the Gordon Highlanders ascended to heaven,

As they stormed the Dargai heights without delay,

And made the Indian rebels fly in great dismay.

“Men of the Gordon Highlanders,” Colonel Mathias said,

“Now, my brave lads, who never were afraid,

Our General says ye must take Dargai heights to-day;

So, forward, and charge them with your bayonets without dismay!”

If he was deliberately writing for laughs, surely we’d expect his work to get technically worse over the years, as he sought for more outrageous comic effect? If he was putting on an act, it was one of the most impressive feats of acting of all time. Was he really able to sustain the same comic character non-stop, both off and on stage, for a period of twenty-five years, or was he just being himself? We shall never know for sure, but the latter seems more likely.

*

Perhaps the most amazing thing about McGonagall is his failure to lapse back into obscurity. The man was remembered fondly for many years after his death by those that had come into contact with him, and his lopsided verse was passed down to subsequent generations. A new edition of Poetic Gems was compiled and printed in the 1930s and it has never gone out of print since.

By the 1960s, his fame had spread south of the border, carried by fans like the actor John Laurie, who would entertain his friends with recitals. The increased interest led to the publication of two further collections of “gems”, More Poetic Gems in 1962 and Last Poetic Gems in 1968.

McGonagall inspired characters in The Goons, Monty Python’s Flying Circus and The Muppet Show. Spike Milligan made a film about him in 1974 and there have been a number of stage shows based upon his life as well. The “Gonnagles”, who appear in several of Terry Pratchett’s books, are very much based on the writer, while J. K. Rowling named Professor McGonagall in the Harry Potter books after him. In addition, there are now several websites dedicated to his life and work, including McGonagall Online (www.mcgonagall-online.org.uk). Not bad for the worst poet in the English language.

McGonagall was a man ahead of his time. One is forced to admire his self-confidence and belief in his own abilities, a conviction which he was able to sustain, despite all evidence to the contrary, throughout his quixotic pursuit of literary status. He would be in his element in today’s age of reality television, where a lack of discernable talent is no impediment to becoming a media celebrity overnight. Perhaps he was just born 150 years too early.

Chris Hunt

October 2006

POETIC GEMS

SELECTED FROM THE WORKS OF

William McGonagall

Poet and Tragedian

Died in Edinburgh 29th September, 1902

WITH

BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH AND REMINISCENCES BY THE AUTHOR

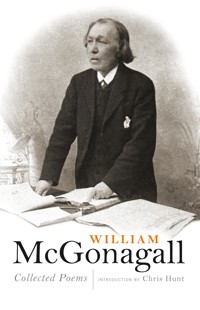

AND PORTRAIT BY D. B. GRAY

CONTENTS

Brief Autobiography

Reminiscences

Tribute to Mr McGonagall from Three Students at Glasgow University

Ode to William McGonagall

Tribute from Zululand

Testimonials

An Ode to the Queen on Her Jubilee Year

The Death of Prince Leopold

The Death of Lord and Lady Dalhousie

The Funeral of the German Emperor

The Battle of Tel-el-Kebir

The Famous Tay Whale

The Railway Bridge of the Silvery Tay

The Newport Railway

The Tay Bridge Disaster

An Address to the New Tay Bridge

The Late Sir John Ogilvy

The Rattling Boy from Dublin

The Burial of the Rev. George Gilfillan

The Battle of El-Teb

The Battle of Abu Klea

A Christmas Carol

The Christmas Goose

An Autumn Reverie

The Wreck of the Steamer “London” while on her way to Australia

The Wreck of the “Thomas Dryden” in Pentland Firth

Attempted Assassination of the Queen

Saving a Train

The Moon

The Beautiful Sun

Grace Darling; or, the Wreck of the “Forfarshire”

To Mr James Scrymgeour, Dundee

The Battle of Bannockburn

Edinburgh

Glasgow

Oban

The Battle of Flodden Field

Greenland’s Icy Mountains

A Tribute to Henry M. Stanley

Jottings of New York

Beautiful Monikie

A Tribute to Mr Murphy and the Blue Ribbon Army

Loch Katrine

Forget-Me-Not

The Royal Review

The Nithsdale Widow and Her Son

Jack o’ the Cudgel: Part I

Part II

The Battle of Culloden

The Battle of Sheriffmuir

The Execution of James Graham, Marquis of Montrose

Baldovan

Loch Leven

Montrose

The Castle of Mains

Broughty Ferry

Robert Burns

Adventures of King Robert the Bruce

A Tale of the Sea

Descriptive Jottings of London

Annie Marshall the Foundling

Bill Bowls the Sailor

Young Munro the Sailor

The Death of the Old Mendicant

An Adventure in the Life of King James V of Scotland

The Clepington Catastrophe

The Rebel Surprise Near Tamai

Burning of the Exeter Theatre

John Rouat the Fisherman

The Sorrows of the Blind

General Gordon, the Hero of Khartoum

The Battle of Cressy

The Wreck of the Barque “Wm. Paterson” of Liverpool

Hanchen, the Maid of the Mill

Wreck of the Schooner “Samuel Crawford”

The First Grenadier of France

The Tragic Death of the Rev. A. H. Mackonochie

The Burning of the Steamer “City of Montreal”

The Wreck of the Whaler “Oscar”

Jenny Carrister, the Heroine of Lucknow-Mine

The Horrors of Majuba

The Miraculous Escape of Robert Allan, the Fireman

The Battle of Shina, in Africa, Fought in 1800

The Collision in the English Channel

The Pennsylvania Disaster

The Sprig of Moss

BRIEF AUTOBIOGRAPHY

DEAR READER, – My parents were both born in Ireland, where they spent the great part of their lives after their marriage. They left Ireland for Scotland, and never returned to the Green Isle. I was born in the year of 1830 in the city of Edinburgh, the garden of bonnie Scotland, which is justly famed by all for its magnificent scenery. My parents were poor, but honest, sober, and God-fearing. My father was a hand-loom weaver, and wrought at cotton fabrics during his stay in Edinburgh, which was for about two years. Owing to the great depression in the cotton trade in Edinburgh, he removed to Paisley with his family, where work was abundant for a period of about three years; but then a crash taking place, he was forced to remove to Glasgow with his family with the hope of securing work there, and enable him to support his young and increasing family, as they were all young at that time, your humble servant included. In Glasgow he was fortunate in getting work as a cotton weaver; and as trade was in a prosperous state for about two years, I was sent to school, where I remained about eighteen months, but at the expiry of which, trade again becoming dull, my poor parents were compelled to take me from school, being unable to pay for schooling through adverse circumstances; so that all the education I received was before I was seven years of age.

My father, being forced to leave Glasgow through want of work, came to Dundee, where plenty of work was to be had at the time – such as sacking, cloth, and other fabrics. It was at this time that your humble servant was sent to work in a mill in the Scouringburn, which was owned by Mr Peter Davie, and there I remained for about four years, after which I was taken from the mill, and put to learn the hand-loom in Ex-Provost Reid’s factory, which was also situated in the Scouringburn. After I had learned to be an expert hand-loom weaver, I began to take a great delight in reading books, as well as to improve my handwriting, in my leisure hours at night, until I made myself what I am.

The books that I liked best to read were Shakespeare’s penny plays, more especially Macbeth, Richard III, Hamlet, and Othello; and I gave myself no rest until I obtained complete mastery over the above four characters. Many a time in my dear father’s absence I enacted entire scenes from Macbeth and Richard III, along with some of my shopmates, until they were quite delighted; and many a time they regaled me and the other actors that had entertained them to strong ale, biscuits, and cheese.

My first appearance on any stage was in Mr Giles’ theatre, which was in Lindsay Street quarry, some years ago: I cannot give the exact date, but it is a very long time ago. The theatre was built of brick, somewhat similar to Mr M‘Givern’s at the top of Seagate. The character that I appeared in was Macbeth, Mrs Giles sustaining the character of Lady Macbeth on that occasion, which she performed admirably. The way that I was allowed to perform was in terms of the following agreement, which was entered into between Mr Giles and myself – that I had to give Mr Giles one pound in cash before the performance, which I considered rather hard, but as there was no help for it, I made known Mr Giles’s terms to my shopmates, who were hand-loom weavers in Seafield Works, Taylor’s Lane. No sooner than the terms were made known to them, than they entered heartily into the arrangement, and in a very short time they made up the pound by subscription, and with one accord declared they would go and see me perform the Thane of Fife, alias Macbeth. To see that the arrangement with Mr Giles was carried out to the letter, a deputation of two of my shopmates was appointed to wait upon him with the pound. Mr Giles received the deputation, and on receipt of the money cheerfully gave a written agreement certifying that he would allow me to perform Macbeth on the following night in his theatre. When the deputation came back with the news that Mr Giles had consented to allow me to make my debut on the following night, my shopmates cheered again and again, and the rapping of the lays I will never forget as long as I live. When the great night arrived my shopmates were in high glee with the hope of getting a Shakespearian treat from your humble servant. And I can assure you, without boasting, they were not disappointed in their anticipations, my shopmates having secured seats before the general public were admitted. It would be impossible for me to describe the scene in Lindsay Street, as it was crowded from head to foot, all being eager to witness my first appearance as an exponent of Shakespeare. When I appeared on the stage I was received with a perfect storm of applause, but when I exclaimed, “Command, they make a halt upon the heath,” the applause was deafening, and was continued during the entire evening, especially so in the combat scene. The house was crowded during each of the three performances on that ever-memorable night, which can never be forgot by me or my shopmates, and even entire strangers included. At the end of each performance I was called before the curtain, and received plaudit after plaudit of applause in recognition of my able impersonation of Macbeth.

What a sight it was to see such a mass of people struggling to gain admission! hundreds failing to do so, and in the struggle numbers were trampled under foot, one man having lost one of his shoes in the scrimmage; others were carried bodily into the theatre along with the press. So much then for the true account of my first appearance on any stage.

The most startling incident in my life was the time I discovered myself to be a poet, which was in the year 1877. During the Dundee holiday week, in the bright and balmy month of June, when trees and flowers were in full bloom, while lonely and sad in my room, I sat thinking about the thousands of people who were away by rail and steamboat, perhaps to the land of Burns, or poor ill-treated Tannahill, or to gaze upon the Trossachs in Rob Roy’s country, or elsewhere wherever their minds led them. Well, while pondering so, I seemed to feel as it were a strange kind of feeling stealing over me, and remained so for about five minutes. A flame, as Lord Byron has said, seemed to kindle up my entire frame, along with a strong desire to write poetry; and I felt so happy, so happy, that I was inclined to dance, then I began to pace backwards and forwards in the room, trying to shake off all thought of writing poetry; but the more I tried, the more strong the sensation became. It was so strong, I imagined that a pen was in my right hand, and a voice crying, “Write! Write!” So I said to myself, ruminating, let me see; what shall I write? then all at once a bright idea struck me to write about my best friend, the late Reverend George Gilfillan; in my opinion I could not have chosen a better subject, therefore I immediately found paper, pen, and ink, and set myself down to immortalize the great preacher, poet, and orator. These are the lines I penned, which I dropped into the box of the Weekly News office surreptitiously, which appeared in that paper as follows:–

“W. M‘G., Dundee, who modestly seeks to hide his light under a bushel, has surreptitiously dropped into our letter-box an address to the Rev. George Gilfillan. Here is a sample of this worthy’s powers of versification;–

‘Rev. George Gilfillan of Dundee,

There is none can you excel;

You have boldly rejected the Confession of Faith,

And defended your cause right well.

‘The first time I heard him speak,

’Twas in the Kinnaird Hall,

Lecturing on the Garibaldi movement,

As loud as he could bawl.

‘He is a liberal gentleman

To the poor while in distress,

And for his kindness unto them

The Lord will surely bless.

‘My blessing on his noble form,

And on his lofty head,

May all good angels guard him while living,

And hereafter when he’s dead.’ ”

P.S. – This is the first poem that I composed while under the divine inspiration, and is true, as I have to give an account to God at the day of judgment for all the sins I have committed.

With regard to my far-famed Balmoral journey, I will relate it truly as it happened. ’Twas on a bright summer morning in the month of July 1878, I left Dundee en route for Balmoral, the Highland home of Her Most Gracious Majesty, Queen of Great Britain and Empress of India. Well, my first stage for the day was the village of Alyth. When I arrived there I felt weary, footsore, and longed for rest and lodgings for the night. I made enquiry for a good lodging-house, and found one very easily, and for the lodging I paid fourpence to the landlady before I sat down, and when I had rested my weary limbs for about five minutes I rose and went out to purchase some provisions for my supper and breakfast – some bread, tea, sugar, and butter – and when I had purchased the provisions I returned to my lodgings and prepared for myself a hearty tea, which I relished very much, I can assure you, for I felt very hungry, not having tasted food of any kind by the way during my travel, which caused me to have a ravenous appetite, and to devour it greedily; and after supper I asked the landlady to oblige me with some water to wash my feet, which she immediately and most cheerfully supplied me with; then I washed my sore blistered feet and went to bed, and was soon in the arms of Morpheus, the god of sleep. Soundly I slept all the night, until the landlady awoke me in the morning, telling me it was a fine sunshiny morning. Well, of course I arose, and donned my clothes, and I felt quite refreshed after the refreshing sleep I had got during the night; then I gave myself a good washing, and afterwards prepared my breakfast, which I devoured quickly, and left the lodging-house, bidding the landlady good morning, and thanking her for her kindness; then I wended my way the next day as far as the Spittal o’ Glenshee –

Which is the most dismal to see –

With its bleak, rocky mountains,

And clear, crystal fountains,

With their misty foam;

And thousands of sheep there together do roam,

Browsing on the barren pasture, blasted-like to see,

Stunted in heather, and scarcely a tree;

And black-looking cairns of stones, as monuments to show,

Where people have been found that were lost in the snow –

Which is cheerless to behold –

And as the traveller gazes thereon it makes his blood run cold,

And almost makes him weep,

For a human voice is seldom heard there,

Save the shepherd crying to his sheep.

The chains of mountains there is most frightful to see,

Along each side of the Spittal o’ Glenshee;

But the Castleton o’ Braemar is most beautiful to see,

With its handsome whitewashed houses, and romantic scenery,

And bleak-looking mountains, capped with snow,

Where the deer and the roe do ramble to and fro,

Near by the dark river Dee,

Which is most beautiful to see.

And Balmoral Castle is magnificent to be seen,

Highland home of the Empress of India, Great Britain’s Queen,

With its beautiful pine forests, near by the river Dee,

Where the rabbits and hares do sport in mirthful glee,

And the deer and the roe together do play

All the live long summer day,

In sweet harmony together,

While munching the blooming heather,

With their hearts full of glee,

In the green woods of Balmoral, near by the river Dee.

And, my dear friends, when I arrived at the Spittal o’ Glenshee, a dreadful thunder-storm came on, and the vivid flashes of the forked lightning were fearful to behold, and the rain poured down in torrents until I was drenched to the skin, and longed to be under cover from the pitiless rain. Still God gave me courage to proceed on my weary journey, until I arrived at a shepherd’s house near by the wayside, and I called at the house, as God had directed me to do, and knocked at the door fearlessly. I was answered by the servant maid, who asked me kindly what I wanted, and I told her I wanted lodgings for the night, and that I was wet to the skin with the rain, and that I felt cold and hungry, and that I would feel thankful for any kind of shelter for the night, as it was still raining and likely to be for the night. Then she told me there was no accommodation; then the shepherd himself came to the door, and he asked me what I wanted, and I told him I wanted a lodging for the night, and at first he seemed unwilling, eyeing me with a suspicious look, perhaps taking me for a burglar, or a sheep-stealer, who had come to steal his sheep – at least that was my impression. But when I showed him Her Most Gracious Majesty’s royal letter, with the royal black seal, that I had received from her for my poetic abilities, he immediately took me by the hand and bade me come in, and told me to “gang in ower to the fire and to warm mysel’,” at the same time bidding the servant maid make some supper ready for the poet; and while the servant girl was making some porridge for me, I showed him a copy of my poems, which I gave to him as a present for his kindness towards me, which he read during the time I was taking my supper, and seemed to appreciate very much. Then when I had taken my supper, he asked me if I would be afraid to sleep in the barn, and I told him so long as I put my trust in God I had nought to fear, and that these were the principles my dear parents had taught me. When I told him so he felt quite delighted, and bade me warm my feet before I would “gang oot to my bed i’ the barn,” and when I had warmed my feet, he accompanied me to the barn, where there was a bed that might have pleased Her Most Gracious Majesty, and rolling down the bed-clothes with his own hands, he wished me a sound sleep, and bade me good-night. Then I instantly undressed and tumbled into bed, and was soon sound asleep, dreaming that I saw Her Most Gracious Majesty riding in her carriage-and-pair, which was afterwards truly verified. Well, when I awoke the next morning I felt rather chilled, owing to the wetting I had got, and the fatigue of the distance I had travelled; but, nothing daunted, I still resolved to see Her Majesty. So I dressed myself quickly, and went over to the house to bid the shepherd good-morning, and thank him for the kindness I had received at his hands, but I was told by the girl he was away tending the sheep, but that he had told her to give me my breakfast, and she bade me come in and sit down and get it. So of course I went in, and got a good breakfast of porridge and good Highland milk, enough to make a hungry soul to sing with joy, especially in a strange country, and far from home. Well, having breakfasted, I arose and bade the servant girl good-bye, at the same time thanking her and the shepherd – her master – for their kindness towards me. Then, taking to the road again, I soon came in sight of the Castleton o’ Braemar, with its beautiful whitewashed houses and romantic scenery, which I have referred to in my poem. When I arrived at the Castleton o’ Braemar it was near twelve o’clock noon, and from the Castleton it is twelve miles to Balmoral; and I arrived at the lodge gates of the palace of Balmoral just as the tower clock chimed three; and when I crossed the little bridge that spans the river Dee, which has been erected by Her Majesty, I walked boldly forward and knocked loudly at the porter lodge door, and it was immediately answered by the two constables that are there night and day, and one of them asked me in a very authoritative tone what I wanted, and of course I told him I wanted to see Her Majesty, and he repeated, “Who do you want to see?” and I said I was surprised to think that he should ask me again after telling him distinctly that I wanted to see Her Majesty. Then I showed him Her Majesty’s royal letter of patronage for my poetic abilities, and he read it, and said it was not Her Majesty’s letter; and I said, “Who’s is it then? do you take me for a forger?” Then he said Sir Thomas Biddulph’s signature was not on the letter, but I told him it was on the envelope, and he looked and found it to be so. Then he said, “Why didn’t you tell me that before?” I said I forgot. Then he asked me what I wished him to do with the letter, and I requested him to show it to Her Majesty or Sir Thomas Biddulph. He left me, pretending to go up to the palace with the letter, standing out in the cold in front of the lodge, wondering if he would go up to the palace as he pretended. However, be that as it may, I know not, but he returned with an answer as follows: – “Well, I’ve been up at the Castle with your letter, and the answer I got for you is they cannot be bothered with you,” said with great vehemence. “Well,” I replied, “it cannot be helped”; and he said it could not, and began to question me when I left Dundee, and the way I had come from Dundee, and where I had lodged by the way; and I told him, and he noted it all down in his memorandum book, and when he had done so he told me I would have to go back home again the same way I came; and then he asked me if I had brought any of my poetry with me, and I said I had, and showed him the second edition, of which I had several copies, and he looked at the front of it, which seemed to arrest his attention, and said, “You are not poet to Her Majesty; Tennyson’s the real poet to Her Majesty.” Then I said, “Granted; but, sir, you cannot deny that I have received Her Majesty’s patronage.” Then he said, “I should like very much to hear you give some specimens of your abilities,” and I said, “Where?” and he said, “Just where you stand”; and I said, “No, sir, nothing so degrading in the open air. When I give specimens of my abilities it is either in a theatre or some hall, and if you want to hear me take me inside of the lodge, and pay me before I begin; then you shall hear me. These are my conditions, sir; do you accept my terms?” Then he said, “Oh, you might to oblige the young lady there.” So I looked around to see the young lady he referred to, and there she was, looking out at the lodge entrance; and when I saw her I said, “No, sir, I will not; if it were Her Majesty’s request I wouldn’t do it in the open air, far less do it to please the young lady.” Then the lady shut the lodge door, and he said, “Well, what do you charge for this book of poems?” and I said “2d.,” and he gave it me, telling me to go straight home and not to think of coming back again to Balmoral. So I bade him good-bye and retraced my steps in search of a lodging for the night, which I obtained at the first farmhouse I called at; and when I knocked at the door I was told to come in and warm my feet at the fire, which I accordingly did, and when I told the good wife and man who I was, and about me being at the palace, they felt very much for me, and lodged me for the night, and fed me likewise, telling me to stay with them for a day or two, and go to the roadside and watch Her Majesty, and speak to her, and that I might be sure she would do something for me, but I paid no heed to their advice. And when I had got my supper, I was shown out to the barn by the gudeman, and there was prepared for me a bed which might have done a prince, and the gudeman bade me good-night. So I closed the barn door and went to bed, resolving to be up very early the next morning and on the road, and with the thought thereof I couldn’t sleep. So as soon as daylight appeared, I got up and donned my clothes, and went to the farmer’s door and knocked, for they had not arisen, it being so early, and I bade them good-bye, thanking them at the same time for their kindness; and in a few minutes I was on the road again for Dundee – it being Thursday morning I refer to – and lodging in the same houses on my homeward journey, which I accomplished in three days, by arriving in Dundee on Saturday early in the day, foot-sore and weary, but not the least discouraged. So ends my ever-memorable journey to Balmoral.

My next adventure was going to New York, America, in the year 1887, March the 10th. I left Glasgow on board the beautiful steamer “Circassia,” and had a very pleasant voyage for a fortnight at sea; and while at sea I was quite a favourite amongst the passengers, and displayed my histronic abilities, to the delight of the passengers, but received no remuneration for so doing; but I was well pleased with the diet I received; also with the kind treatment I met with from the captain and chief steward – Mr Hendry. When I arrived at Castle Garden, New York, I wasn’t permitted to pass on to my place of destination until the officials there questioned me regarding the place in New York I was going to, and how old I was, and what trade I was; and, of course, I told them I was a weaver, whereas if I had said I was a poet, they wouldn’t have allowed me to pass, but I satisfied them in their interrogations, and was allowed to pass on to my place of destination. During my stay in New York with a Dundee man, I tried occasionally to get an engagement from theatrical proprietors and music-hall proprietors. But alas! ’twas all in vain, for they all told me they didn’t encourage rivalry, but if I had the money to secure a hall to display my abilities, or a company of my own, I would make lots of money; but I am sorry to say I had neither, therefore I considered wisely it was time to leave, so I wrote home to a Dundee gentleman requesting him to take me home, and he granted my request cheerfully, and secured for me a passage on board the “Circassia” again, and I had a very pleasant return voyage home again to bonnie Dundee. Since I came home to Dundee I have been very well treated by the more civilised community, and have made several appearances before the public in Baron Zeigler’s circus and Transfield’s circus, to delighted and crowded audiences; and the more that I was treated unkindly by a few ignorant boys and the Magistrates of the city, nevertheless my heart still clings to Dundee; and, while in Glasgow, my thoughts, night and day, were always towards Dundee; yet I must confess, during a month’s stay in Glasgow, I gave three private entertainments to crowded audiences, and was treated like a prince by them, but owing to declining health, I had to leave the city of Glasgow. Since this Book of Poems perhaps will be my last effort, –

I earnestly hope the inhabitants of the beautiful city of Dundee

Will appreciate this little volume got up by me,

And when they read its pages, I hope it will fill their hearts with delight,

While seated around the fireside on a cold winter’s night;

And some of them, no doubt, will let a silent tear fall In dear remembrance of

WILLIAM MCGONAGALL.

REMINISCENCES

MY DEARLY BELOVED READERS, – I will begin with giving an account of my experiences amongst the publicans. Well, I must say that the first man who threw peas at me was a publican, while I was giving an entertainment to a few of my admirers in a public-house in a certain little village not far from Dundee; but, my dear friends, I wish it to be understood that the publican who threw the peas at me was not the landlord of the public-house, he was one of the party who came to hear me give my entertainment. Well, my dear readers, it was while I was singing my own song, “The Rattling Boy from Dublin Town,” that he threw the peas at me. You must understand that the Rattling Boy was courting a lass called Biddy Brown, and the Rattling Boy chanced to meet his Biddy one night in company with another lad called Barney Magee, which, of course, he did not like to see, and he told Biddy he considered it too bad for her to be going about with another lad, and he would bid her good-bye for being untrue to him. Then Barney Magee told the Rattling Boy that Biddy Brown was his lass, and that he could easily find another – and come and have a glass, and be friends. But the Rattling Boy told Barney Magee to give his glass of strong drink to the devil! meaning, I suppose, it was only fit for devils to make use of, not for God’s creatures. Because, my friends, too often has strong drink been the cause of seducing many a beautiful young woman away from her true lover, and from her parents also, by a false seducer, which, no doubt, the Rattling Boy considered Barney Magee to be. Therefore, my dear friends, the reason, I think, for the publican throwing the peas at me is because I say, to the devil with your glass, in my song, “The Rattling Boy from Dublin,” and he, no doubt, considered it had a teetotal tendency about it, and, for that reason, he had felt angry, and had thrown the peas at me.

My dear readers, my next adventure was as follows: – During the Blue Ribbon Army movement in Dundee, and on the holiday week of the New-year, I was taken into a public-house by a party of my friends and admirers, and requested to give them an entertainment, for which I was to be remunerated by them. Well, my friends, after the party had got a little refreshment, and myself along with the rest, they proposed that I should give them a little entertainment, which I most willingly consented to do, knowing I would be remunerated by the company for so doing, which was the case; the money I received from them I remember amounted to four shillings and sixpence. All had gone on as smoothly as a marriage bell, and every one of the party seemed to be highly delighted with the entertainment I had given them. Of course, you all ought to know that while singing a good song, or giving a good recitation, it helps to arrest the company’s attention from the drink; yes! in many cases it does, my friends. Such, at least, was the case with me – at least the publican thought so – for – what do you think? – he devised a plan to bring my entertainment to an end abruptly, and the plan was, he told the waiter to throw a wet towel at me, which, of course, the waiter did, as he was told, and I received the wet towel, full force, in the face, which staggered me, no doubt, and had the desired effect of putting an end to me giving any more entertainments in his house. But, of course, the company I had been entertaining felt angry with the publican for being guilty of such a base action towards me, and I felt indignant myself, my friends, and accordingly I left the company I had been entertaining and bade them good-bye. My dear friends, a publican is a creature that would wish to decoy all the money out of the people’s pockets that enter his house; he does not want them to give any of their money away for an intellectual entertainment. No, no! by no means; give it all to him, and crush out entertainment altogether, thereby he would make more money if he could only do so. My dear friends, if there were more theatres in society than public-houses, it would be a much better world to live in, at least more moral; and oh! my dear friends, be advised by me. Give your money to the baker, and the butcher, also the shoemaker and the clothier, and shun the publicans; give them no money at all, for this sufficient reason, they would most willingly deprive us of all moral entertainment if we would be as silly as to allow them. They would wish us to think only about what sort of strong drink we should make use of, and to place our affections on that only, and give the most of our earnings to them; no matter whether your families starve or not, or go naked or shoeless; they care not, so as their own families are well clothed from the cold, and well fed. My dear friends, I most sincerely entreat of you to shun the publicans as you would shun the devil, because nothing good can emanate from indulging in strong drink, but only that which is evil. Turn ye, turn ye! why be a slave to the bottle? Turn to God, and He will save you.

I hope the day is near at hand,

When strong drink will be banished from our land.

I remember a certain publican in the city that always pretended to have a great regard for me. Well, as I chanced to be passing by his door one day he was standing in the doorway, and he called on me to come inside, and, as he had been in the habit of buying my poetry, he asked me if I was getting on well, and, of course, I told him the truth, that I was not getting on very well, that I had nothing to do, nor I had not been doing anything for three weeks past, and, worse than all, I had no poetry to sell. Then he said that was a very bad job, and that he was very sorry to hear it, and he asked me how much I would take to give an entertainment in his large back-room, and I told him the least I would take would be five shillings. Oh! very well, he replied, I will invite some of my friends and acquaintances for Friday night first, and mind, you will have to be here at seven o’clock punctual to time, so as not to keep the company waiting. So I told him I would remember the time, and thanked him for his kindness, and bade him good-bye. Well, when Friday came, I was there punctually at seven o’clock, and, when I arrived, he told me I was just in time, and that there was a goodly company gathered to hear me. So he bade me go ben to the big room, and that he would be ben himself – as I supposed more to look after the money than to hear me give my entertainment. Well, my readers, when I made my appearance before the company I was greeted with applause, and they told me they had met together for the evening to hear me give my entertainment. Then a round of drink was called for, and the publican answered the call. Some of the company had whisky to drink, and others had porter or ale, whichever they liked best; as for myself, I remember I had gingerbeer. Well, when we had all partaken of a little drink, it was proposed by some one in the company that a chairman should be elected for the evening, which seemed to meet with the publican’s approbation. Then the chairman was elected, and I was introduced to the company by the chairman as the great poet McGonagall, who was going to give them an entertainment from his own productions; hoping they would keep good order and give me a fair hearing, and, if they would, he was sure I would please them. And when he had delivered himself so, he told me to begin, and accordingly I did so, and entertained the company for about an hour and a half. The company was highly satisfied with the entertainment I gave them, and everyone in the company gave threepence each, or sixpence each – whatever they liked, I suppose – until it amounted to five shillings. Then the chairman told the publican that five shillings had been subscribed anent the entertainment I had given, and handed it to him. Then the publican gave it to me, and I thanked him and the company for the money I received from them anent the entertainment I had given them. Then the chairman proposed that I should sing “The Rattling