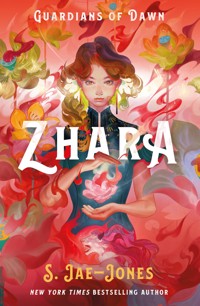

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Serie: Wintersong

- Sprache: Englisch

All her life, Liesl has heard tales of the beautiful, dangerous Goblin King. They've enraptured her and inspired her musical compositions. Now eighteen, Liesl feels that her childhood dreams are slipping away. And when her sister is taken by the Goblin King, Liesl has no choice but to journey to the Underground to save her. But with time and the old laws working against her, Liesl must discover who she truly is before her fate is sealed.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 554

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Overture

Part I

Beware the Goblin Men

Come Buy, Come Buy

She is for The Goblin King now

Virtuoso

The Audition

The Tall, Elegant Stranger

Intermezzo

The Ideal Imaginary

A Pretty Lie

The Ugly Truth

Sacrifice

Part II

Fairy Lights

Eyes Open

The Games We’ve Played

The Bride

The Old Laws

Strange, Sweet

Pyrrhic Victory

Resurrection

Part III

Consecration

The Wedding

Wedding Night

Prick and Bleed

Those Who have Come Before

Come Out to Play

Changeling

Mercy

Romance in C Major

Part IV

Death and The Maiden

Perchance to Dream

Unfinished Symphony

The Threshold

Zugzwang

Justice

Be, Thou, With Me

The Brave Maiden’s Tale

The Mystery Sonatas

The Return

Immortal Beloved

Acknowledgments

About the Author

WintersongPrint edition ISBN: 9781785655449E-book edition ISBN: 9781785655456

Published by Titan BooksA division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

First edition: February 201710 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This book is a work of fiction. Any references to historical events, real people, or real places are used fictitiously. Other names, characters, places, and events are products of the author’s imagination, and any resemblance to actual events or places or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2017 by S. Jae-Jones.All rights reserved.

Illustration courtesy of the author.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

For , for being the best fairy-tale grandmother of all time .

OVERTURE

Once there was a little girl who played her music for a little boy in the wood. She was small and dark, he was tall and fair, and the two of them made a fancy pair as they danced together, dancing to the music the little girl heard in her head.

Her grandmother had told her to beware the wolves that prowled in the wood, but the little girl knew the little boy was not dangerous, even if he was the king of the goblins.

Will you marry me, Elisabeth? the little boy asked, and the little girl did not wonder at how he knew her name.

Oh, she replied, but I am too young to marry.

Then I will wait, the little boy said. I will wait as long as you remember.

And the little girl laughed as she danced with the Goblin King, the little boy who was always just a little older, a little out of reach.

As the seasons turned and the years passed, the little girl grew older but the Goblin King remained the same. She washed the dishes, cleaned the floors, brushed her sister’s hair, yet still ran to the forest to meet her old friend in the grove. Their games were different now, truth and forfeit and challenges and dares.

Will you marry me, Elisabeth? the little boy asked, and the little girl did not yet understand his question was not part of a game.

Oh, she replied, but you have not yet won my hand.

Then I will win, the little boy said. I will win until you surrender.

And the little girl laughed as she played against the Goblin King, losing every hand and every round.

Winter turned to spring, spring to summer, summer into autumn, autumn back into winter, but each turning of the year grew harder and harder as the little girl grew up while the Goblin King remained the same. She washed the dishes, cleaned the floors, brushed her sister’s hair, soothed her brother’s fears, hid her father’s purse, counted the coins, and no longer went into the woods to see her old friend.

Will you marry me, Elisabeth? the Goblin King asked.

But the little girl did not reply.

PART I

THE GOBLIN MARKET

We must not look at goblin men,We must not buy their fruits:Who knows upon what soil they fedTheir hungry, thirsty roots?

CHRISTINA ROSSETTI, GOBLIN MARKET

BEWARE THE GOBLIN MEN

“Beware the goblin men,” Constanze said. “And the wares they sell.”

I jumped when my grandmother’s shadow swept across my notes, scattering my thoughts and foolscap along with it. I scrambled to cover my music, shame shaking my hands, but Constanze hadn’t been addressing me. She stood perched on the threshold, scowling at my sister, Käthe, who primped and preened before the mirror in our bedroom—the only mirror in our entire inn.

“Listen well, Katharina.” Constanze pointed a gnarled finger at my sister’s reflection. “Vanity invites temptation, and is the sign of a weak will.”

Käthe ignored her, pinching her cheeks and fluffing her curls. “Liesl,” she said, reaching for a hat on the dressing table. “Could you come help me with this?”

I put my notes back into their little lockbox. “It’s a market, Käthe, not a ball. We’re just going to pick up Josef’s bows from Herr Kassl’s.”

“Liesl,” Käthe whined. “Please.”

Constanze harrumphed and thumped the floor with her cane, but my sister and I paid her no heed. We were used to our grandmother’s dour and direful pronouncements.

I sighed. “All right.” I hid the lockbox beneath our bed and rose to help pin the hat to Käthe’s hair.

The hat was a towering confection of silk and feathers, a ridiculous affectation, especially in our little provincial village. But my sister was also ridiculous, so she and the hat were well matched.

“Ouch!” Käthe said as I accidentally jabbed her with a hatpin. “Watch where you stick that thing.”

“Learn to dress yourself, then.” I smoothed down my sister’s curls and settled her shawl so that it covered her bare shoulders. The waist of her gown was gathered high beneath her bosom, the simple lines of her dress showing every curve of her figure. It was, Käthe claimed, the latest fashion in Paris, but my sister seemed scandalously unclothed to my eyes.

“Tut.” Käthe preened before her reflection. “You’re just jealous.”

I winced. Käthe was the beauty of our family, with sunshine hair, summer-blue eyes, apple-blossom cheeks, and a buxom figure. At seventeen, she already looked like a woman full-grown, with a small waist and generous hips that her new dress showed off to great advantage. I was nearly two years older but still looked like a child: small, thin, and sallow. The little hobgoblin, Papa called me. Fey, was Constanze’s pronouncement. Only Josef ever called me beautiful. Not pretty, my brother would say. Beautiful.

“Yes, I’m jealous,” I said. “Now, are we going to the market or not?”

“In a bit.” Käthe rummaged through her box of trinkets. “What do you think, Liesl?” she asked, holding up a few lengths of ribbon. “Red or blue?”

“Does it matter?”

She sighed. “I suppose not. None of the village boys will care anymore, now that I’m to be married.” She glumly plucked at the trim on her gown. “Hans isn’t the sort for fun or finery.”

My lips tightened. “Hans is a good man.”

“A good man, and boring,” Käthe said. “Did you see him at the dance the other night? He never, not once, asked me to take a turn with him. He just stood in the corner and glared disapprovingly.”

It was because Käthe had been flirting shamelessly with a handful of Austrian soldiers en route to Munich to oust the French. Pretty girl, they coaxed her in their funny Austrian accents, Come give us a kiss!

“A wanton woman is ripened fruit,” Constanze intoned, “begging to be plucked by the Goblin King.”

A frisson of unease ran up my spine. Our grandmother liked to scare us with tales of goblins and other creatures that lived in the woods beyond our village, but Käthe, Josef, and I hadn’t taken her stories seriously since we were children. At eighteen, I was too old for my grandmother’s fairy tales, yet I cherished the guilty thrill that ran through me whenever the Goblin King was mentioned. Despite everything, I still believed in the Goblin King. I still wanted to believe in the Goblin King.

“Oh, go squawk at someone else, you old crow.” Käthe pouted. “Why must you always be pecking at me?”

“Mark my words.” Constanze glared at my sister from beneath layers of yellowed lace and faded ruffles, her dark brown eyes the only sharp things in her wizened face. “You watch yourself, Katharina, lest the goblins come take you for your licentious ways.”

“Enough, Constanze,” I said. “Leave Käthe alone and let us go on our way. We must be back before Master Antonius arrives.”

“Yes, Heaven forbid we miss our precious little Josef’s audition for the famous violin maestro,” my sister muttered.

“Käthe!”

“I know, I know.” She sighed. “Stop worrying, Liesl. He’ll be fine. You’re worse than a hen with a fox at the door.”

“He won’t be fine if he doesn’t have any bows to play with.” I turned to leave. “Come, or I’ll be going without you.”

“Wait.” Käthe grabbed my hand. “Would you let me do a little something with your hair? You have such gorgeous locks; it’s a shame you plait them out of the way. I could—”

“A wren is still a wren, even in a peacock’s feathers.” I shook her off. “Don’t waste your time. It’s not like Hans—anyone—would notice anyway.”

My sister flinched at the mention of her betrothed’s name. “Fine,” she said shortly, then strode past me without another word.

“Ka—” I began, but Constanze stopped me before I could follow.

“You take care of your sister, girlie,” she warned. “You watch over her.”

“Don’t I always?” I snapped. It had always been up to me—me and Mother—to hold the family together. Mother looked after the inn that was our house and livelihood; I looked after the members who made it home.

“Do you?” My grandmother fixed her dark eyes on my face. “Josef isn’t the only one who needs looking after, you know.”

I frowned. “What do you mean?”

“You forget what day it is.”

Sometimes it was easier to humor Constanze than to ignore her. I sighed. “What day is it?”

“The day the old year dies.”

Another shiver up my spine. My grandmother still kept to the old laws and the old calendar, and this last night of autumn was when the old year died and the barrier between worlds was thin. When the denizens of the Underground walked the world above during the days of winter, before the year began again in the spring.

“The last night of the year,” Constanze said. “Now the days of winter begin and the Goblin King rides abroad, searching for his bride.”

I turned my face away. Once I would have remembered without any prompting. Once I would have joined my grandmother in pouring salt along every windowsill, every threshold, every entrance as a precaution against these wildling nights. Once, once, once. But I could no longer afford the luxury of my indulgent imaginings. It was time, as the apostle Paul said to the Corinthians, to put aside childish things.

“I don’t have time for this.” I pushed Constanze aside. “Let me pass.”

Sorrow pushed the lines of my grandmother’s face into even deeper grooves, sorrow and loneliness, her hunched shoulders bowing with the weight of her beliefs. She bore those beliefs alone now. None of us kept faith with Der Erlkönig anymore; none save Josef.

“Liesl!” Käthe shouted from downstairs. “Can I borrow your red cloak?”

“Mind how you choose, girl,” Constanze told me. “Josef is not part of the game. When Der Erlkönig plays, he plays for keeps.”

Her words stopped me short. “What are you talking about?” I asked. “What game?”

“You tell me.” Constanze’s expression was grave. “The wishes we make in the dark have consequences, and the Lord of Mischief will call their reckoning.”

Her words prickled against my mind. I minded how Mother warned us of Constanze’s aged and feeble wits, but my grandmother had never seemed more lucid or more earnest, and despite myself, a thread of fear began to wind about my throat.

“Is that a yes?” Käthe called. “Because I’m taking it if so!”

I groaned. “No, you may not!” I said, leaning over the stair rail. “I’ll be right there, I promise!”

“Promises, eh?” Constanze cackled. “You make so many, but how many of them can you keep?”

“What—” I began, but when I turned to face her, my grandmother was gone.

* * *

Downstairs, Käthe had taken my red cloak off its peg, but I plucked it from her hands and settled it about my own shoulders. The last time Hans had brought us gifts from his father’s fabric goods store—before his proposal to Käthe, before everything between us changed—he had given us a beautiful bolt of heavy wool. For the family, he’d said, but everyone had known the gift was for me. The bolt of wool was a deep blood-red, perfectly suited to my darker coloring and warming to my sallow complexion. Mother and Constanze had made me a winter cloak from the cloth, and Käthe made no secret of how much she coveted it.

We passed our father playing dreamy old airs on his violin in the main hall. I looked around for our guests, but the room was empty, the hearth cold and the coals dead. Papa still wore his clothes from the night before, and the whiff of stale beer lingered about him like mist.

“Where’s Mother?” Käthe asked.

Mother was nowhere to be seen, which was probably why Papa felt bold enough to play out here in the main hall, where anyone might hear him. The violin was a sore point between our parents; money was tight, and Mother would rather Papa play his instrument for hire than pleasure. But perhaps Master Antonius’s imminent arrival had loosened Mother’s purse strings as well as her heartstrings. The renowned virtuoso was to stop at our inn on his way from Vienna to Munich in order to audition my little brother.

“Likely taking a nap,” I ventured. “We were up before dawn, scrubbing out the rooms for Master Antonius.”

Our father was a violinist nonpareil, who had once played with the finest court musicians in Salzburg. It was in Salzburg, Papa would boast, where he had had the privilege of playing with Mozart, one of the late, great composer’s concertos. Genius like that, Papa said, comes only once in a lifetime. Once in two lifetimes. But sometimes, he would continue, giving Josef a sly glance, lightning does strike twice.

Josef was not among the gathered guests. My little brother was shy of strangers, so he was likely hiding at the Goblin Grove, practicing until his fingers bled. My heart ached to join him, even as my fingertips twinged with sympathetic pain.

“Good, I won’t be missed,” Käthe said cheerfully. My sister often found any excuse to skip out on her chores. “Let’s go.”

Outside, the air was brisk. The day was uncommonly cold, even for late autumn. The light was sparse, weak and wavering, as though seen through curtains or a veil. A faint mist wrapped the trees along the path into town, wraithing their spindly branches into spectral limbs. The last night of the year. On a day like this, I could believe the barriers between worlds were thin indeed.

The path that led into town was pitted and rutted with carriage tracks and spotted with horse dung. Käthe and I took care to keep to the edges, where the short, dead grass helped prevent the damp from seeping into our boots.

“Ugh.” Käthe stepped around another dung puddle. “I wish we could afford a carriage.”

“If only our wishes had power,” I said.

“Then I’d be the most powerful person in the world,” Käthe remarked, “for I have wishes aplenty. I wish we were rich. I wish we could afford whatever we wanted. Just imagine, Liesl: what if, what if, what if.”

I smiled. As little girls, Käthe and I were fond of What if games. While my sister’s imagination did not encompass the uncanny, as mine and Josef’s did, she had an extraordinary capacity for pretend nonetheless.

“What if, indeed?” I asked softly.

“Let’s play,” she said. “The Ideal Imaginary World. You first, Liesl.”

“All right.” I thought of Hans, then pushed him aside. “Josef would be a famous musician.”

Käthe made a face. “It’s always about Josef with you. Don’t you have any dreams of your own?”

I did. They were locked up in a box, safe and sound beneath the bed we shared, never to be seen, never to be heard.

“Fine,” I said. “You go, then, Käthe. Your Ideal Imaginary World.”

She laughed, a bright, bell-like sound, the only musical thing about my sister. “I am a princess.”

“Naturally.”

Käthe shot me a look. “I am a princess, and you are a queen. Happy now?”

I waved her on.

“I am a princess,” she continued. “Papa is the Prince-Bishop’s Kapellmeister, and we all live in Salzburg.”

Käthe and I had been born in Salzburg, when Papa was still a court musician and Mother a singer in a troupe, before poverty chased us to the backwoods of Bavaria.

“Mother is the toast of the city for her beauty and her voice, and Josef is Master Antonius’s prize pupil.”

“Studying in Salzburg?” I asked. “Not Vienna?”

“In Vienna, then,” Käthe amended. “Oh yes, Vienna.” Her blue eyes sparkled as she spun out her fantasy for us. “We would travel to visit him, of course. Perhaps we’ll see him perform in the great cities of Paris, Mannheim, and Munich, maybe even London! We shall have a grand house in each city, trimmed with gold and marble and mahogany wood. We’ll wear gowns made in the most luxurious silks and brocades, a different color for every day of the week. Invitations to the fanciest balls and parties and operas and plays shall flood our post every morning, and a bevy of swains will storm the barricades for our favor. The greatest artists and musicians would consider us their intimate acquaintances, and we would dance and feast all night long on cake and pie and schnitzel and—”

“Chocolate torte,” I added. It was my favorite.

“Chocolate torte,” Käthe agreed. “We would have the finest coaches and the handsomest horses and”—she squeaked as she slipped in a mud puddle—“never walk on foot through unpaved roads to market again.”

I laughed, and helped her regain her footing. “Parties, balls, glittering society. Is that what princesses do? What of queens? What of me?”

“You?” Käthe fell silent for a moment. “No. Queens are destined for greatness.”

“Greatness?” I mused. “A poor, plain little thing like me?”

“You have something much more enduring than beauty,” she said severely.

“And what is that?”

“Grace,” she said simply. “Grace, and talent.”

I laughed. “So what is to be my destiny?”

She cut me a sidelong glance. “To be a composer of great renown.”

A chill wind blew through me, freezing me to the marrow. It was as though my sister had reached into my breast and wrenched out my heart, still beating, with her fist. I had jotted down small snatches of melody here and there, scribbling little ditties instead of hymns into the corners of my Sunday chapbook, intending to gather them into sonatas and concertos, romances and symphonies someday. My hopes and dreams, so tattered and tender, had been sheltered by secrecy for so long that I could not bear to bring them to light.

“Liesl?” Käthe tugged at my sleeve. “Liesl, are you all right?”

“How—” I said hoarsely. “How did you …”

She squirmed. “I found your box of compositions beneath our bed one day. I swear I didn’t mean any harm,” she added quickly. “But I was looking for a button I’d dropped, and …” Her voice trailed off at the look upon my face.

My hands were shaking. How dare she? How dare she open my most private thoughts and expose them to her prying eyes?

“Liesl?” Käthe looked worried. “What’s wrong?”

I did not answer. I could not answer, not when my sister would never understand just how she had trespassed against me. Käthe had not a modicum of musical ability, nearly a mortal sin in a family such as ours. I turned and marched down the path to market.

“What did I say?” My sister hurried to catch up with me. “I thought you’d be pleased. Now that Josef’s going away, I thought Papa might—I mean, we all know you have just as much talent as—”

“Stop it.” The words cracked in the autumn air, snapping beneath the coldness of my voice. “Stop it, Käthe.”

Her cheeks reddened as though she had been slapped. “I don’t understand you,” she said.

“What don’t you understand?”

“Why you hide behind Josef.”

“What does Sepperl have to do with anything?”

Käthe narrowed her eyes. “For you? Everything. I bet you never kept your music secret from our little brother.”

I paused. “He’s different.”

“Of course he’s different.” Käthe threw up her hands in exasperation. “Precious Josef, delicate Josef, talented Josef. He has music and madness and magic in his blood, something poor, ordinary, tone-deaf Katharina does not understand, could never understand.”

I opened my mouth to protest, then shut it again. “Sepperl needs me,” I said softly. It was true. Our brother was fragile, in more than just bones and blood.

“I need you,” she said, and her voice was quiet. Hurt.

Constanze’s words returned to me. Josef isn’t the only one who needs looking after.

“You don’t need me.” I shook my head. “You have Hans now.”

Käthe stiffened. Her lips went white, her nostrils flared. “If that’s what you think,” she said in a low voice, “then you’re even crueler than I thought.”

Cruel? What did my sister know of cruelty? The world had shown her considerably more favor than it had ever shown me. Her prospects were happy, her future certain. She would marry the most eligible man in the village while I became the unwanted sister, the discarded one. And I … I had Josef, but not for long. When my little brother left, he would take the last of my childhood with him: our revels in the woods, our stories of kobolds and Hödekin dancing in the moonlight, our games of music and make-believe. When he was gone, all that would remain to me was music—music and the Goblin King.

“Be grateful for what you have,” I snapped back. “Youth, beauty, and, very soon, a husband who will make you happy.”

“Happy?” Käthe’s eyes flashed. “Do you honestly think Hans will make me happy? Dull, boring Hans, whose mind is as limited as the borders of the stupid, provincial village in which he grew up? Stolid, dependable Hans, who would keep me rooted to the inn with a deed in my hand and a baby in my lap?”

I was stunned. Hans was an old friend of the family, and while he and Käthe had not been close as children—as Hans and I had been—I had not known until this moment just how little my sister loved him. “Käthe,” I said. “Why—”

“Why did I agree to marry him? Why haven’t I said anything before now?”

I nodded.

“I did.” Tears welled up in her eyes. “Over and over. But you never listened. This morning, when I said he was boring, you told me he was a good man.” She turned her face away. “You never hear a word I say, Liesl. You’re too busy listening to Josef instead.”

Mind how you choose. Guilt clotted my throat.

“Oh, Käthe,” I whispered. “You could have said no.”

“Could I?” she scoffed. “Would you or Mother have let me? What choice did I have but to accept his hand?”

Her accusation gutted me, made me complicit in my own resentment. I had been so sure that this was the way of the world that I hadn’t questioned it. Handsome Hans and beautiful Käthe—of course they were meant to be together.

“You have choices,” I repeated uncertainly. “More than I ever will.”

“Choices, ha.” Käthe’s laugh was raw. “Well, Liesl, you made your choice about Josef a long time ago. You can’t fault me for making mine about Hans.”

The rest of our walk to the market continued without another word.

COME BUY, COME BUY

Come buy, come buy!

In the town square, the market stalls were laden with goods, their sellers hawking their wares at the top of their lungs. Fresh bread! Fresh milk! Goat cheese! Warm wool, the softest wool you’ve ever felt! Some vendors rang bells, some rattled wooden clappers, and still others beat an erratic rat-a-tat-tat on a homemade drum, all in an effort to bring custom to their tables. As we drew nearer, Käthe began to brighten.

I never did understand the prospect of spending coin for pleasure, but my sister loved to shop. She ran her fingers lovingly over the fabrics on sale: silks and velvets and satins imported from England, Italy, and even the Far East. She buried her nose in bouquets of dried lavender and rosemary, and closed her eyes as she savored the tart taste of mustard on the doughy pretzel she had bought. Such sensuous enjoyment.

I trailed behind, lingering over wreaths of dried flowers and ribbons, thinking I might buy one as a wedding gift for my sister—or an apology. Käthe loved beautiful things; no, more than loved—reveled in them. I noted how the sour-lipped matrons and stern-browed elders of the town gave my sister dark looks, as though her thorough delight in small luxuries was something obscene, something dirty. One man in particular, a tall, pale, elegant shade of a man, watched her with an intensity that would have ignited me, had he but glanced my way.

Come buy, come buy!

A group of fruit-sellers on the fringes of the market called in high, clear voices that carried over the din of the crowd. Their silvery, chime-like tones tingled the ear, drawing me close, almost against my will. It was late in the season for fresh fruit, and I marked the unusual color and texture of their offerings: round, luscious, tempting.

“Ooh, Liesl!” Käthe pointed, our earlier argument forgotten. “Peaches!”

The fruit-sellers beckoned us with fluid gestures, holding their wares in their hands, and the tantalizing scent of ripe fruit wafted past. My mouth watered, but I turned away, pulling Käthe with me. I had no coin to spare.

A few weeks ago, I had sent for a few of Josef’s bows to be re-haired and repaired by an archetier before my brother’s audition with Master Antonius. I had hoarded, scrimped, and saved what I could, for repairs did not come cheap.

But now the fruit-sellers had caught sight of us and our longing glances. “Come, lovely ladies!” they sang. “Come, sweet darlings. Come buy, come buy!” One of them tapped out a rhythm on the wooden planks that served as their table, while the others took up a melody. “Damsons and apricots, peaches and blackberries, taste them and try!”

Without thinking, I began to sing with them, a wordless ooh-oo searching for harmony and counterpoint in their music. Thirds, fifths, diminished sevenths, I played with the chords beneath my breath. Together, the fruit-sellers and I wove a shimmering web of sound, haunting, strange, and a little wild.

The vendors suddenly focused their eyes on me, their features sharpening, their smiles lengthening. The hairs on the back of my neck stood on end and I let the melody drop. The touch of their eyes was a tickle on my skin, but behind me I could sense the gaze of an unseen other, as palpable as a hand caressing my nape. I glanced over my shoulder.

The tall, pale, elegant stranger.

His features were shadowed by a hood, but beneath the cloak, his clothes were fine. I noted the glint of gold and silver thread on green velvet brocade. Seeing my inquisitive expression, the stranger stirred and folded his cloak about him, but not before I caught a glimpse of dun-colored leather breeches outlining the slim shape of his hips. I turned my face away, my blush heating the air about me. He seemed familiar, somehow.

“Brava, brava!” the fruit-sellers cried once they had finished their song. “Clever maiden in red, come take your reward!”

They waved their hands over the fruits on display, their fingers long and slim. For a moment, it seemed as though there were too many joints in their fingers, and I felt the brush of something uncanny. But that moment passed, and the merchants picked up a peach, offering it to me with open hands.

The fruit’s perfume was thick on the chill autumn air, but beneath the cloying smell was the tang of something rotten, something putrid. I recoiled, and it seemed to me these sellers’ appearances had changed. Their skin had taken on a greenish tinge, the tips of their teeth were pointed and sharp, and instead of fingernails, they seemed to have claws.

Beware the goblin men, and the wares they sell.

Käthe reached for the peach with both hands. “Oh yes, please!”

I grabbed my sister’s shawl and yanked her back.

“The maiden knows what she wants,” said one of the vendors. He grinned at Käthe, but it was more leer than smile. His lips seemed stretched a little too far, his yellowed teeth sharp. “Full of passions, full of desire. Easily spent, easily satiated.”

Spooked, I turned to Käthe. “Let’s go,” I said. “We shouldn’t tarry. We need to stop by Herr Kassl’s before heading home.”

Käthe’s eyes remained fixed on the array of fruit laid before her. She looked sick, her brows furrowed, her bosom heaving, her cheeks flushed, her eyes bright and feverish. She looked sick, or … excited. A feeling of wrongness settled over me, wrongness and fear, even as a hint of her excitement roused my own limbs.

“Let’s go,” I repeated. Käthe’s eyes were dull and glassy. “Anna Katharina Magdalena Ingeborg Vogler!” I snapped. “We are leaving.”

“Perhaps another time then, dearie,” sneered the fruit-seller. I gathered my sister close, draping one arm protectively about her shoulders. “She’ll be back,” he said. “Girls like her can never put off temptation for long. Both are … ripe for the plucking.”

I walked away, pushing Käthe ahead of me. Out of the corner of my eye, I glimpsed the tall, elegant stranger again. From beneath his hood, I sensed him watching us. Watching. Considering. Judging. One of the fruit-sellers tugged at the stranger’s cloak, and the man bent his head to listen, but I felt his gaze upon us. Upon me.

“Beware.”

I stopped in my tracks. It was another one of the fruit-sellers, a smallish man with frizzy hair like a thistle cloud and a pinched face. He wasn’t more than the size of a child, although his expression was old, older than Constanze, older than the forest itself.

“That one,” the merchant said, pointing to Käthe, whose head lolled against my shoulder, “burns like kindling. All flash, and no real heat. But you,” he said. “You smolder, mistress. There is a fire burning within you, but it is a slow burn. It shimmers with heat, waiting only for a breath to fan it to life. Most curious.” A slow grin spread over his mouth. “Most curious, indeed.”

The merchant vanished. I blinked, but he never returned, leaving me to wonder if I had dreamed the encounter. I shook my head, tightened my grip on Käthe’s arm, and marched toward Herr Kassl’s shop, determined to forget these strange goblin men and their fruits: so tantalizing, so sweet, and so very far out of reach.

* * *

Käthe shook me off as we drew away from the fruit-sellers. “I’m not a child what needs looking after, you know,” she snapped.

I tightened my lips, biting back my sharp retort. “Fine.” I held out a small purse. “Go find Johannes the brewer and tell him—”

“I know what I’m doing, Liesl,” she said, snatching the purse from my hand. “I’m not completely helpless.”

And with that she flounced away from me, disappearing into the hustle and bustle of the crowd.

With some misgiving, I turned and found my way to Herr Kassl’s. We had no bow-maker or luthier in our little village, but Herr Kassl knew all the best craftsmen in Munich. During his long acquaintance with our family, Herr Kassl had seen many valuable instruments pass through his shop, and therefore made it his business to maintain contact with those in the trade. He was an old friend of Papa’s, insofar as a pawnbroker could be a friend.

Once I had finished conducting business with Herr Kassl, I went in search of my sister. Käthe was easy to find, even in this sea of faces in the square. Her smiles were the broadest, her blue eyes the brightest, her pink cheeks the rosiest. Even her hair beneath that ridiculous hat shone like a bird of golden plumage. All I had to do was follow the path traced by the eyes of the onlookers in the village, those admiring, appreciative glances that led me straight to my sister at the center.

For a moment, I watched her bargain and haggle with the sellers. Käthe was like an actress on the stage, all heightened emotion and intense passion, her gestures affected, her smiles calculated. She fluttered and flirted outrageously, carefully oblivious to the stares she drew like moths to the flame. Both men and women traced the lines of her body, the curve of her cheek, the pout of her lip.

Looking at Käthe, it was difficult to forget just how sinful our bodies were, just how prone we were to wickedness. Born unto trouble, as the sparks fly upward, or so saith Job. Clothed in clinging fabrics, with every line of her body exposed, every gasp of pleasure unconcealed, everything about Käthe suggested voluptuousness.

With a start, I realized I was looking at a woman—a woman and not a child. Käthe knew of the power her body wielded over others, and that knowledge had replaced her innocence. My sister had crossed the threshold from girl to woman without me, and I felt abandoned. Betrayed. I watched a young man fawn over my sister as she perused his booth, and a lump rose in my throat, resentment so bitter I nearly choked on it.

What I wouldn’t have given to be the object of someone’s desire, just for one moment. What I wouldn’t have given to taste that fruit, that heady sweetness, of being wanted. I wanted. I wanted what Käthe took for granted. I wanted wantonness.

“Might I interest the young lady in red in a few curious trinkets?”

Startled from my reverie, I looked up to see the tall, elegant stranger once more.

“No, thank you, sir.” I shook my head. “I have no money to spare.”

The stranger stepped closer. In his gloved hands he held a flute, beautifully carved and polished to a high shine. Up close, I could see the gleam of his eyes from beneath the hood.

“No? Well, then, if you won’t buy my wares, would you accept a gift?”

“A—a gift?” I was hot and uncomfortable beneath his scrutiny. He looked at me as no one had before, as though I were more than the sum of my eyes, my nose, my lips, my hair, and my wretched plainness. He looked as though he saw me entire, as though he knew me. But did I know him? His presence scratched at my mind, like a half-remembered song. “What for?”

“Do I need a reason?” His voice was neither deep nor high, but there was a quality to it that spoke of dark woods and dry winter nights. “Perhaps I just wanted to make a young woman’s day a little bit brighter. The nights grow long and cold, after all.”

“Oh no, sir,” I said again. “My grandmother warned me against the wolves that prowl in the woods.”

The stranger laughed, and I caught a glimpse of sharp, white teeth. I shivered.

“Your grandmother is wise,” he said. “I’m sure she also told you to avoid the goblin men. Or perhaps she told you we were one and the same.”

I did not answer.

“You are clever. I do not offer this gift to you out of the goodness of my heart, but out of a selfish need to see what you might do with it.”

“What do you mean?”

“There is music in your soul. A wild and untamed sort of music that speaks to me. It defies all the rules and laws you humans set upon it. It grows from inside you, and I have a wish to set that music free.”

He had heard me sing with the fruit-sellers. A wild, untamed sort of music. I’d heard those words before, from Papa. Then, it had seemed like an insult. My musical education had been rudimentary at best; of us all, Papa had taken the most time and care with Josef, making sure my brother understood the theory and history of music, its building blocks and foundations. I had always listened in on the edges of those lessons, taking whatever notes I could, applying them slipshod to my own compositions.

But this elegant stranger cast no judgment on my lack of formal structure, my lack of learning. I took his words and planted them deep inside.

“For you, Elisabeth.” He offered me the flute again. This time I took it. Despite the cold air, the instrument was warm, and felt almost like skin beneath my hands.

It was only after the stranger disappeared that I realized he had called me by my given name.

Elisabeth.

How could he have possibly known?

* * *

I held the flute in my hands, admiring its build, running my fingers over its rich grain and smooth finish. A persistent thought niggled at the back of my mind, a sense I had lost or forgotten something, but it hovered on the edges of memory, a word on the tip of my tongue.

Käthe.

A jolt of fear stirred my sluggish thoughts. Käthe, where was Käthe? In the milling crowd, there was no sign of my sister’s ridiculous confectionary hat, nor an echo of her chiming laugh. A deep sense of dread overcame me, along with the troubling feeling that I had been tricked.

Why had that tall, elegant stranger offered me a gift? Was it truly out of selfish curiosity for my sake, or just another ploy to distract me while the goblin men stole my sister away?

I thrust the flute into my satchel and picked up the hems of my skirts, ignoring the scandalized glances of the town fussbudgets and the hooting calls of village ne’er-do-wells. I ran through the market in a blind panic, calling Käthe’s name.

Reason warred with faith. I was too old to indulge in the stories of my childhood, but I could not deny the strangeness of my encounter with the fruit-sellers. With the tall, elegant stranger.

They were the goblin men.

There were no goblin men.

Come buy, come buy!

The spectral voices of the merchants were faint and thin on the breeze, more memory than sound. I followed that thread of music, hearing its eerie melodies not with my ears, but with another part of me, unseen and unnoticed. The music reached into my heart and tugged, pulling me along like a puppet on its strings.

I knew where my sister had gone. Terror seized me, along with the unquestioned certainty that something bad will happen if I did not reach her in time. I had promised to keep my sister safe.

Come buy, come buy!

The voices were softer now, distant and hollow, fading into silence with a ghostly whisper. I reached the edges of the market, but the fruit-sellers were no longer there. There were no stalls, no tables, no tents, no fruit, nothing to suggest they had ever been there. Nothing save Käthe’s lonely form in the mist, her flimsy dress fluttering about her like one of the White Ladies of Frau Perchta, like a figure from one of Constanze’s fairy tales. Perhaps I had reached my sister in time. Perhaps there was nothing to fear.

“Käthe!” I cried, running to embrace her.

She turned around. My sister’s lips glistened—red, sticky, and sweet—her pout swollen as though she had just been thoroughly kissed.

In her hands was a half-eaten peach, its juice dripping down her fingers like rivulets of blood.

SHE IS FOR THE GOBLIN KING NOW

Käthe did not speak to me on our walk home. I was nursing a foul mood myself: my irritation with my sister, the unsettling encounter with the fruit-sellers, the shivery longing the tall, elegant stranger had stirred in me—all swirled together into a maelstrom of confusion. A misty quality shrouded my memories of the market, and I could not be certain if it hadn’t all been a dream.

Yet nestled in my satchel was the stranger’s gift. The flute jostled against my leg with every step, as real as Josef’s bows in my hand. I wondered why the stranger had gifted the flute to me. I was a mediocre flautist at best; the thin, ghostly sounds I could produce on the instrument were more strange than sweet. I wondered how I would explain its existence to Mother. I wondered how I could explain it to myself.

“Liesl.”

To my surprise, it was Josef who greeted us at the door. He peered at us from around the posts, hovering uncomfortably on the threshold.

“What is it, Sepp?” I asked gently. I knew my brother was nervous about his upcoming audition, what it would cost him to show his face to so many strangers. Like me, my brother hid in the shadows; unlike me, he preferred it there.

“Master Antonius,” he whispered, “is here.”

“What?” I dropped my satchel. “So soon?” We hadn’t expected the old violin master until the evening.

He nodded. A wary expression crossed his face, his pale features pinched with worry. “He made good time over the Alps. Didn’t want to get caught out by an early snowstorm.”

“He needn’t have worried,” Käthe said. Both Josef and I turned to look at her in surprise. Our sister was gazing into the distance, her eyes a glassy glaze. “The king still sleeps, waiting. The days of winter have not yet begun.”

My pulse beat hard. “Who’s sleeping? Who’s waiting?”

But she said no more, and merely walked past Josef into the inn.

My brother and I exchanged a glance. “Is she all right?” he asked.

I bit my lip, remembering how the goblin fruit had stained her lips and chin with something like blood. Then I shook my head. “She’s fine. Where is Master Antonius now?”

“Upstairs, taking a nap,” Josef said. “Mother told us not to disturb him.”

“And Papa?”

Josef slid his gaze from mine. “I don’t know.”

I closed my eyes. Of all the moments for Papa to disappear. The old violin virtuoso had been a friend of Papa’s from the Prince-Bishop’s court. Both Master Antonius and Papa had left those days behind them, but one had traveled further than the other. One had just finished a post as a visiting resident at the court of the Austrian emperor, while the other found solace at the bottom of a beer barrel every night.

“Well.” I opened my eyes and forced my lips into a smile. I handed Josef his newly repaired bows and gathered an arm about his shoulders. “Let’s get ready to put on a show, shall we?”

* * *

The kitchen was a flurry of baking, boiling, broiling. “Good, you’re back,” Mother said shortly. She nodded at a bowl on the counter. “The meat is spiced, so start trimming the lengths.” She stood over a large vat of boiling water, stirring a batch of sausages.

I put on an apron and immediately began measuring the sausage casing to twist and tie into individual links. Käthe was nowhere to be seen, so I sent Josef to go look for her.

“Have you seen your father?” Mother asked.

I dared not look at her face. Mother was an extraordinarily lovely woman, her figure still slim and youthful, her hair still bright, her skin still fair. In the half-light of dusk and dawn, in the in-between hours, in the golden edge of a candle flame, one could see how she had been renowned throughout Salzburg not only for her beautiful voice, but for her beautiful face as well. But time had graven lines at the corners of her full lips and between her brows. Time, toil, and Papa.

“Liesl.”

I shook my head.

She sighed, and a world of meaning lay within that sound. Anger, frustration, hopelessness, resignation. Mother still had the gift of conveying every shade of emotion through voice and voice alone.

“Well,” she said. “Let us pray Master Antonius won’t take offense to his absence.”

“I’m sure Papa will be back in time.” I picked up a knife to hide the lie. Trim, twist, tie. Trim, twist, tie. “We must have faith.”

“Faith.” My mother laughed, but it was a bitter sound. “You can’t live on faith, Liesl. You can’t feed your family with it.”

Twist, trim, tie. Twist, trim, tie. “You know how charming Papa can be,” I said. “He could coax the trees to bear fruit in winter, he can be forgiven any slight.”

“Yes, I certainly know how charming your father can be,” Mother said drily.

I flushed; I had been born only five months after my parents said their vows.

“Charm is all well and good,” she said, straining the sausages and setting them on a towel to dry. “But charm doesn’t put bread on the table. Charm goes out with his friends at night when he could be showing his son to all the great masters himself.”

I did not reply. It had been a dream of the family’s once, to take Josef to the capital cities of the world and play his talent for better, richer ears. But we never did tour Josef. And now, at fourteen, my brother was too old to be touted as a child prodigy the way the Mozarts or Linley had, too young to be appointed to any sort of permanent post as a professional musician. Despite his skill, my brother still had years left to learn and perfect his craft, and if Master Antonius did not take him on as an apprentice, then it would be the end of Josef’s career.

So there was a great deal of hope riding on Josef’s audition, not just for Josef, but for all of us. It was my brother’s opportunity to rise beyond his humble beginnings and show the world what a talent he was, but it was also our father’s last chance to play for all the great audiences of Europe through his son. For Mother, it was a way for her youngest child to escape the life of drudgery and hardship that came with an innkeeper’s lot, and for Käthe, it was the possibility of visiting her famous brother in all the capital cities: Mannheim, Munich, Vienna, and possibly even London, Paris, or Rome.

For me … it was a way for my music to reach ears beyond just Josef’s and mine. Käthe might have seen my secret scribblings hidden in the box beneath our bed, but only Josef had ever heard its contents.

“Hans!” Mother said. “I didn’t expect to see you here so early.”

The knife in my hand slipped. I cursed under my breath, sucking at the cut to draw out the blood.

“I wouldn’t miss Josef’s big day, Frau Vogler,” Hans said. “I came to help.”

“Bless you, Hans,” Mother said affectionately. “You’re a godsend.”

I ripped a strip from my apron to wrap around my bleeding finger and continued working, trying my best to remain unnoticed. He is your sister’s betrothed, I reminded myself. Yet I couldn’t help but steal glances at him from beneath my lashes.

Our eyes met, and all warmth left the room. Hans cleared his throat. “Good morning, Fräulein,” he said.

His careful distance stung worse than the cut on my finger. We had been familiar, once. Once upon a time, we had been Hansl and Liesl. Once upon a time we had been friends, or perhaps something more. But that was before we all grew up.

“Oh, Hans.” I gave an awkward laugh. “We’re almost family. You can still call me Liesl, you know.”

He nodded stiffly. “It’s good to see you, Elisabeth.”

Elisabeth. It was as intimate as we’d ever be now. I forced a smile. “How are you?”

“I am well, I thank you.” His brown eyes were guarded. “And you?”

“Fine,” I said. “A little nervous. About the audition, I mean.”

Hans’s expression softened. He came closer and took a knife from the cutting board, joining me in twisting, trimming, and tying the sausages. “You needn’t worry,” he said. “Josef plays like an angel.”

He smiled, and the frost between us began to thaw. We settled into the rhythm of our work—trim, twist, tie, trim, twist, tie—and for a moment, I could pretend it was as it had been when we were children. Papa had given us keyboard and violin lessons together, and we had sat upon the same bench, learned the same scales, shared the same lessons. Though Hans never progressed much beyond simple exercises, we spent hours together at the klavier, our shoulders brushing, our hands never touching.

“Where is Josef, anyway?” asked Hans. “Out playing in the Goblin Grove?”

Hans, like the rest of us, had sat at Constanze’s feet, listening to her stories of kobolds and Hödekin, of goblins and Lorelei, of Der Erlkönig, the Lord of Mischief. Warm feelings began to flicker between us like embers.

“Perhaps,” I said softly. “It is the last night of the year.”

Hans scoffed. “Isn’t he too old to be playing fairies and goblins?”

His contempt was a dash of cold water, quenching the remnants of our shared youth.

“Liesl, can you come watch the vat?” Mother asked, wiping the sweat from her brow. “The brewers are to arrive at any moment.”

“I’ll do it, ma’am,” Hans offered.

“Thank you, my dear,” she said. She relinquished the stirring rod to Hans and walked out of the kitchen, wiping her hands on her apron, leaving us alone.

We did not speak.

“Elisabeth,” Hans began tentatively.

Twist, trim, tie. Twist, trim, tie.

“Liesl.”

My hands paused for the briefest moment, and then I resumed my work. “Yes, Hans?”

“I—” He cleared his throat. “I had hoped to catch you alone.”

That caught my attention. Our eyes met, and I found myself staring at him, bold-faced and direct. He was less handsome than I was wont to remember him, his chin less strong, his eyes closer set, his lips pinched and thin. But no one could deny that Hans was a good-looking man, least of all me.

“Me?” My voice was hoarse, but steady. “Why?”

His dark eyes studied my face, a wrinkle of uncertainty appearing between his brows. “I … I want to make things right between us, Lies—Elisabeth.”

“Are they not?”

“No.” Hans stared at the swirling vat in front of him before setting his stirring rod aside, stepping closer to me. “No, they’re not. I … I’ve missed you.”

Suddenly it was hard to breathe. Hans seemed too big, too close, too much.

“We were good friends once, weren’t we?” he asked.

“We were.”

I could not concentrate through the nearness of him. His lips formed words, but I did not hear them, only felt the brush of his breath against my own lips. I held myself rigid, wanting to push into him, knowing I should pull away.

Hans grabbed my wrist. “Liesl.”

Startled, I stared at where his fingers were wrapped around my arm. For so long, I had wanted to touch him, to take his hands and feel those fingers entwined with my own. Yet the moment Hans touched me of his own accord seemed unreal to me. It was as though I were looking at someone else’s hand and someone else’s wrist.

He was not mine. He could not be mine.

Could he?

“Katharina is gone.”

Constanze had wandered into the kitchen. Hans and I leaped apart, but my grandmother did not notice the flush in my cheeks. “Katharina is gone,” she said again.

“Gone?” I struggled to gather my fallen composure and cover my exposed longing. “What do you mean? Gone where?”

“Just gone.” She sucked at a loose tooth.

“I sent Josef to fetch her.”

She shrugged. “She’s not anywhere in the inn, and your red cloak is missing.”

“I’ll go look for her,” Hans offered.

“No, I will,” I said hurriedly. I needed to put my mind and body back into their proper spaces. I needed to get away from him and find myself in the woods.

My grandmother’s dark eyes bored into me. “How did you choose, girlie?” she asked softly. She was hunched over her gnarled cane like a bird of prey, her black shawl draped over her shoulders like crow’s wings.

The memory of the goblin fruit’s bloody flesh running down my sister’s face and fingers returned to me. Josef is not the only who needs looking after. I felt sick.

“Hurry,” Constanze urged. “I fear she is for the Goblin King now.”

I ran out of the kitchen and into the great hall, wiping my hands on my apron. I took a shawl from the rack, wrapped it about my shoulders, and went in search of my sister.

* * *

I did not venture far into the woods, thinking Käthe would keep close to home. Unlike Josef or me, she had never felt any particular kinship with the trees and stones and babbling brooks in the forest. She did not like mud, or dirt, or damp, and preferred to stay inside, where it was warm, where she might primp and be pampered.

Yet my sister was in none of her usual haunts. Ordinarily, the farthest she ventured was to the stables (we owned no horses, but the guests occasionally traveled on horseback), and sometimes to the woodshed, where the tame grasses surrounding our inn ended and the wild edges of the forest began.

There was the faint, impossible scent of summer peaches ripening on the breeze.

Constanze’s warning echoed in my mind. She is for the Goblin King now. I wrapped my shawl tighter about me and hurried off the footpath into the woods.

Past the woodshed, past the creek that ran behind our inn, deep in the wild heart of the forest, was a circle of alder trees we called the Goblin Grove. The trees grew in such a way as to suggest twisted arms and monstrous limbs frozen in an eternal dance, and Constanze liked to tell us that the trees had once been humans—naughty young women—who displeased Der Erlkönig. As children we had played here, Josef and me, played and sang and danced, offering our music to the Lord of Mischief. The Goblin King was the silhouette around which my music was composed, and the Goblin Grove was the place my shadows came to life.

I spied a scarlet shape in the woods ahead of me. Käthe in my cloak, walking to my sacred space. An irrational, petty slash of irritation cut through my dread and unease. The Goblin Grove was my haunt, my refuge, my sanctuary. Why must she take everything that was mine? My sister had a gift for turning the extraordinary into the ordinary. Unlike my brother and me—who lived in the ether of magic and music—Käthe lived in the world of the real, the tangible, the mundane. Unlike us, she never had faith.

Mist curled in about the edges of my vision, blurring the distance between spaces, making near seem far and far seem near. The Goblin Grove was but a few minutes’ walk from our inn, but time seemed to be playing tricks on me, and it felt as though I had been walking both forever and not at all.

Then I remembered time—like memory—was just another one of the Goblin King’s playthings, a toy he could bend and stretch at will.

“Käthe!” I called. But my sister did not hear me.

As a child, I’d pretended to see him, Der Erlkönig, this mysterious ruler underground. No one knew what he looked like, and no one knew what his true nature was, but I did. He looked like a boy, a youth, a man, whatever I needed him to be. He was playful, serious, interesting, confusing, but he was my friend, always my friend. It was make-believe, true, but even make-believe was a sort of belief.

But those were the imaginings of a little girl, Constanze told me. The Goblin King was none of the things I knew him to be. He was the Lord of Mischief—mercurial, melancholy, seductive, beautiful—but he was, above all, dangerous.

Dangerous? little Liesl had asked. Dangerous how?

Dangerous as a winter wind, which freezes the marrow from within, and not like a blade, which slashes the throat from without.

But I was not to worry, for only beautiful women were vulnerable to the Goblin King’s charms. They were his weakness, and he was theirs; they wanted him—sinuous and fey and untamable—the way they wanted to hold on to candle flame or mist. Because I was not beautiful, I never felt the weight of Constanze’s warnings about the Goblin King. Because Käthe was not imaginative, she never had either.

And now I feared for us both.

“Käthe!” I called again.

I picked up my skirts and my pace, running after my sister. But no matter how quickly I ran, the distance between us never closed. Käthe continued walking in her slow, steady way, yet I never managed to overtake her. She was as far from me as when I had first set out after her.

My sister stepped into the Goblin Grove and paused. She glanced over her shoulder, straight at me, but she never saw me. Her eyes scanned the woods, searching for something—or someone—specific.

Suddenly she wasn’t alone. There in the Goblin Grove, standing by my sister’s side as though he had always been there, was the tall, elegant stranger from the marketplace. He wore his cloak and hood, which hid his face from me, but Käthe gazed up at him with a look of adoration.

I stopped in my tracks. Käthe had a strange little smile on her face, a smile I had never seen before, the thin, weak smile of an invalid facing a new day. Her lips looked bitten, and her skin was wan and pale. I felt bizarrely betrayed, by Käthe or the tall, elegant stranger, I wasn’t sure. I did not know him, but he had seemed to know me. He was just another thing Käthe had taken from me, another thing she had stolen. Wasn’t he?

I was about to march straight into the Goblin Grove and drag my sister back home to safety when the stranger drew back his hood.

I gasped.

I could say the stranger was beautiful, but to describe him thus was to call Mozart “just a musician.” His beauty was that of an ice storm, lovely and deadly. He was not handsome, not the way Hans was handsome; the stranger’s features were too long, too pointed, too alien. There was a prettiness about him that was almost girly, and an ugliness about him that was just as compelling. I understood then what Constanze had meant when those doomed young ladies longed to hold on to him the way they yearned to grasp candle flame or mist. His beauty hurt, but it was the pain that made it beautiful. Yet it was not his strange and cruel beauty that moved me, it was the fact that I knew