1,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Reading Essentials

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Amid the blazing colors of a New England autumn, lovely Brooke Reyburn finds perilous mystery and pulse-racing romance!

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

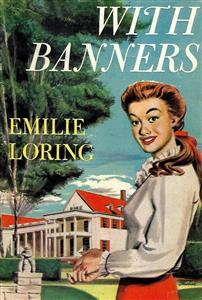

With Banners

by Emilie Loring

First published in 1934

This edition published by Reading Essentials

Victoria, BC Canada with branch offices in the Czech Republic and Germany

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, except in the case of excerpts by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review.

With Banners

Emilie Loring

I

With a nice sense of dramatic values, the heel of Brooke Reyburn's shoe turned sharply as she ran across the street. She went down on one knee just as the traffic light turned green. She had a confused sense of an automobile bearing down on her, the screech of brakes, of panting cars, of arms lifting her to the sidewalk.

"Hurt?" a voice demanded.

She was conscious of the sticky dampness of one knee even as she shook her head and dazedly looked about. The gold dome of the State House shone in the afternoon sun; boys were calling the headlines of the evening papers; an autogiro was crawling like a huge spider across the blue ceiling of the sky. She was still in the world. For one horrible instant she had thought she might be passing out of it; her heart beat like a tom-tom.

She looked up into the eyes blazing down at her. She must have had a narrow escape to have wiped the color from the man's face. It was chalky. Even the lips below his clipped dark mustache were colorless.

"I'm all right, really I am. It was my silly heel that threw me," she assured breathlessly, even as she moved her knee experimentally. It worked. It wasn't broken.

"Why wear such fool heels? If you're not hurt, why did you wince?"

The man's voice was husky; his eyes had a third-degree intentness which roused a little demon of opposition. Brooke retorted crisply:

"If you insist upon probing the secrets of my young life, I think I've skinned my knee."

"Perhaps that skinned knee will teach you not to sprint across the street against the traffic light. I almost lost my mind when I saw you go down just as that car cut around the corner. Don't you know better than to try such a foolish stunt?"

Even making allowance for his fright and for the fact that a man usually roared at the nearest woman when frightened, he had no right to speak to her as if she were a dumbbell. Wasn't it maddening enough to fall in the middle of a city street without being lectured for it? Brooke's eyes flashed up to his.

"At least I know better than to stand on a street corner talking to a stranger," she retorted in a voice which was fiercely satisfying to the tumult within her.

She thought the man spoke as she merged in the stream of passers-by. She passed the building to which she had been hurrying to keep an appointment when she crossed the street. She wouldn't go in yet, she'd better wait till her still thumping heart quieted before she entered the offices of Stewart and Stewart, Attorneys at Law, she had too much pride to appear there breathless and shaken. That had been a narrow escape, not only for her, but for the man who had snatched her from the path of that speeding car, and—horrible thought—she hadn't even said "Thank you!"

Her cheeks burned as she remembered the risk he had taken for her and her abrupt and ungracious departure. He had made it clear enough when he had deposited her on her feet on the sidewalk that he thought her brain quite devoid of gray matter. Her apparent ingratitude wouldn't send her stock up.

If only she knew who he was she could write to him, but he might have been a stranger passing through the city whom she never would see again. In that case she would have to bear always this pricking sense of being ashamed of herself, it would bring her sitting straight up in bed when she thought of it at night.

She stopped at a flower shop. Its color and beauty were like a soothing hand on her smarting conscience. The air had but a hint of the crispness of early October. It was so mild that great pots of chrysanthemums, white, yellow, pink, rusty-orange, and browny-red, were massed under gay awnings. There was a flat dish of rosy japonicas in the window; gladioli, dozens of them; spikes of heavenly blue larkspur; violets, deeply purple, by the alluring bunch; unbelievably perfect Templar roses in crimson masses, and a tray of gardenias in waxy perfection.

Overhead a steeple clock chimed. The sound reminded Brooke of her engagement. She winced as she moved. The words of her rescuer flashed through her mind:

"Perhaps that skinned knee will teach you not to sprint across the street against the traffic light."

Dictator! She made a little disdainful face as his flashed on the screen of her mind. To shake off the memory she glanced again at the flower-shop window. The violets were ravishing. How she would like a bunch but—no "but" about it now, she could buy them. Hadn't she incredibly and miraculously acquired a fortune?

The fragrance of the purple flowers tucked into the green tweed jacket of her suit helped unbelievably to keep her mind off her smarting knee and pricking conscience as she entered the office of the junior partner of Stewart and Stewart. No one here?

After a furtive look about, she examined her knee. Skinned. She had known it. Shreds of her silk stocking clung to the raw flesh. She winced as her lowered skirt scraped it. Her unknown rescuer and dictator need not fear that she would forget that lesson in a hurry.

Where was Mr. Jed Stewart?

There was an open book on his large flat desk. The title fairly jumped at her.

UNDERWOOD ON WILLS

Brooke's heart did a nose-dive. Did that particular book on that particular desk mean that Stewart and Stewart were preparing to contest the will in which she had been named residuary legatee?

Silly, she derided herself, wasn't the firm executor of the estate of Mary Amanda Dane? Hadn't Mr. Jed Stewart notified her that the will had been allowed, hadn't he asked her to be at his office today at four? It was her late shake-up and this gloomy room which had started her imagination on the rampage. Where it wasn't knotty pine it was walled with books impressively, if mustily, bound in calf. An Indian drugget, worn thin under the swivel chair at the desk, covered the floor. The brass top of a massive inkwell glowed red gold where a vagrant ray from the slanting sun struck it. Heavy rust-color hangings framed the windows. No wonder the electric lights were on at this time in the afternoon.

From outside came faint distant noises in the corridor; footsteps thudding, scuffing, springing past; the incessant clang of elevator doors. Inside, "Tick-tock! Tick-tock!" the wall clock marked time for the quick procession of the minutes.

And the minutes were marching along. Where was Mr. Stewart? Was it part of legal procedure to keep clients in suspense? The secretary in the outer office had shown her into this room, had said that she was expected, that the junior partner was in conference but would be at liberty in a few moments.

She compared her wrist watch with the clock. When she had dashed across the street, she had thought she was late for the appointment, she had been detained at the store. She had been in business long enough to realize what it meant to keep a person waiting, that time was money. The rumble of voices in an adjoining office drifted through an open transom. If only Jed Stewart would cut his conference short and tell her why he had sent for her. If the legacy was to be held up, she would like to know. She hated uncertainty.

Restlessly she crossed to the window. She slipped behind one of the hangings to shut off the electric light in the room behind her. What a view! Roofs. Tiers of roofs alive with pigeons. Patches of bright blue broke up the pattern of gray clouds. Weather vanes pointed to the north. Innumerable wires etched gigantic cobwebs against the sky. Skylights shone like sheets of molten brass as they reflected the sun. Flags were flying. Smoke from chimneys was blowing out as straight as the tails of kites in action. Huge signs glimmered with faint lights. Far away on the hazy violet horizon a white spire pointed the way to Heaven. The beat of drums, the shrill of a traffic whistle, the wail of a siren on a fireboat in the harbor pierced the muted roar and rattle, the rhythmic, vibrant throb of the city which rose from the street thirty floors below, pierced even the deafening thunder of the wings of the night mail as it passed overhead.

Her eyes lingered on the roofs. Beneath them business units were pitched together. Honesty and fraud; virtue and vice; ups and downs; efficiency and stupidity; ambition and lethargy; each unit moving in its own orbit and each thinking itself of supreme importance in the complicated pattern of the business world. She ought to know something of that world. She had been buffeting her way in it for five years.

Had been. Her throat tightened. Could she really use that tense? Was it possible that in future she need not squeeze every nickel until the buffalo on it bucked? Was it true that while everyone she knew was adapting expenses to meet a reduced income, a small fortune had dropped into her lap from an absolutely clear sky? It was a "Through the Looking-glass" reversal. It had a fairy-story quality, it belonged in Once upon a Time land—but—she touched the violets, it was true.

"Miss Reyburn ought to be here, Mark, but I suppose like the majority of women she has no idea of the value of a man's time."

The annoyed comment in the room behind her snapped Brooke out of her reflections. How like a man to assume that she was at fault. She would make a dramatic entrance, and then—

"Glad she is late. I told you, Jed, that I didn't want to meet her. It was a beau geste for her to offer me half of the money, all of which should be mine by inheritance. I'll make my get-away before she comes. Let her move into Lookout House pronto. I'm the only person in the world with the right to contest Aunt Mary Amanda Dane's will, and, much as I would like to own the family heirlooms and add her part of the house to mine, I won't do that. I would have to prove 'undue influence' or 'unsound mind,' wouldn't I? How could I do that when under oath I would have to acknowledge that my aunt had said she would cut me out of her will? The fact that I didn't believe she would do it wouldn't cut any ice with the Court. Nothing doing. I've had publicity enough over my domestic casualty to last the rest of my life."

Brooke's hand dropped from the hanging. That must be Mark Trent's deep voice tinged with anger. By "her" did he mean herself? So he thought her offer to share with him merely a beau geste. Should she have refused to take any of the legacy? This was hardly the tactful moment to make her entrance. He was going. As soon as the door closed, she would appear and explain to Mr. Stewart why she had been at the window; meantime she would be strictly honorable and not listen. She stuffed her fingers into her ears.

At the same moment on the other side of the hangings, Jed Stewart was saying:

"I never did understand why Lookout House was cut in two, Mark."

"It wasn't. Grandfather Trent had two houses built exactly alike, one for his daughter, Mary Amanda, and one for his son, my father; the Other House, the family called ours. Not satisfied with that, he had them set side by side on a rocky promontory—he intended them for summer homes only—with doors through the library downstairs and the hall on the second floor and connecting balconies; he was a glutton for balconies. Aunt Mary Amanda recently has lived there the year round. I inherited Father's house, but I haven't lived there since—well, for three years. It has been closed. I haven't rented it because I thought it might be unpleasant for my aunt to have strangers near when she was wheeled into the garden which serves for both places. Now, see what she does to me. She picks up this girl and later, while I'm starting a branch office in South America, leaves her her half of the real estate and all her money. Well, I'll be off. I have a date."

"Don't go, Mark. I asked Miss Reyburn to come here this afternoon to tell her what financial arrangements have been made for her, but principally to get you two face to face so that we could straighten out this mess about the personal property in the house."

"Mess! Do you call a sound, unbreakable will a mess? Aunt Mary Amanda Dane warned me that if I married Lola she would cut me off with the proverbial shilling; then, when my divorce became necessary, she was more opposed to it than she had been to the marriage. Can you beat that for inconsistency? I've always had a hunch that the French man and wife who have worked for and worked Mary Amanda for years might hypnotize her into leaving all her property to them—I warned her against them and somehow they found out and have hated me ever since—but I didn't think she would leave it to a comparative stranger. In my opinion, Clotilde and Henri Jacques are no better than a couple of bandits; they'll bear watching. I don't trust the Reyburn female either, her fine Italian hand crops up all through that will, but I don't like the idea of a girl living in the same house with them. However, she'd probably think I had an axe to grind if I warned her. Why in heaven's name didn't you give me a hint how the property was going?"

"Yellow journals and hectic fiction to the contrary, lawyers don't talk about the affairs of a client, even to their best friend, fella."

"Don't blow up like a pouter pigeon, Jed. Of course I didn't expect you to tell me; equally, of course, I wouldn't try to upset that will. My aunt's High Church convictions wouldn't permit her to approve of my separation from a wife who had been sordidly unfaithful. I thought she might soften toward me when Lola married the third time, but evidently not. If she wanted to bequeath her house, her money, and her jewels to a girl she had picked up via radio, okay. But perhaps you can tell me where all the money she left came from? I knew that she inherited half of Grandfather Trent's property, but I hadn't supposed that her husband, Dane, left much. About five hundred thousand, you said?"

"Plus, and all in savings banks and gilt-edge securities, that is, as gilt-edge as any investment, these days. Can you beat that for a mild little crippled old lady who looked as if she didn't dare call her soul her own?"

"And who lived as if the big bad wolf of a moneyless future were forever sniffing at her door. I about laugh my head off when I think of the cheque I sent her each month with which to buy a few little luxuries, knowing how incomes had been cut—I thought it must take all of hers to keep her home going—the money was a long delayed return for the fun I had visiting her when I was a kid. Mother wouldn't live in our half of the house, but for years I spent Thanksgiving with Aunt Mary Amanda. I hadn't thought she had much of a sense of humor, but she must have crackled with it when she dropped my small cheques into her fat bank account."

"But she didn't drop them into her bank account, Mark. Have you forgotten her reference to that in the will?"

"Not a chance. I know it by heart. She kept the money in a separate deposit, which was to be paid to me with interest. She had accepted it because she thought it good discipline for a youth in this wild generation to deny himself for someone else. Why didn't she tell me about the Reyburn female? Why not ask me to meet her before I went to South America? That's what makes me suspicious. The secrecy of their friendship. Was the girl afraid that if I knew I would try to influence my aunt against her? If I was so dense, how do you suppose she got wise to Mary Amanda's fortune? I understand that she had supper and spent a night with her once a week, the night the companion-nurse had off. She must have had a strong motive to commute twenty miles after business hours. She's a fashion adviser in one of the big shops, isn't she?"

"Yep. Worked up from a model. Mary Amanda Dane tuned in on the radio one morning just as Brooke Reyburn was giving her fashion talk. She fell in love with her voice, and wrote to the girl asking what the well-dressed invalid tied to a wheel chair was wearing. Miss Reyburn answered with such sympathetic understanding that your aunt invited her to Lookout House."

"It's a fairy story brought up to date. Only, for the spell of a witch, substitute the broadcast of a girl's voice. The little schemer got not only the money but Mary Amanda's jewels, many of which were my grandmother's."

Brooke dropped her hands from her ears after what seemed hours. Still talking? Perhaps Jed Stewart was talking to the office boy. She heard him say:

"Your aunt said in her will, remember, that if she left the jewels to you, you might—well, that Miss Reyburn would appreciate them. She relented toward you to the extent of naming you legatee should the girl die without children; she was canny enough to prevent her fortune from falling into the hands of her family. You wouldn't think Brooke Reyburn a schemer if you saw her; you'd know that she had a background of cultivated living. She has a vivid face with a deep dimple at one corner of her lovely mouth; her voice is sweet, spiced with daring. She came out of college to carry her whole darn family when her father died—he was one of the tragic twenty-niners whose investments were wiped out—now, I suppose, her brother, who is acting in a stock company, and her sister will chuck their jobs and settle down on her. Her hair is like copper with the sun on it; her eyes change from brown to amber, and when she smiles at me I feel as cocky as a drum major at the head of a regiment."

"Help! You're raving, Jed. Perhaps you're thinking of marrying her?"

"Marry her yourself, Mark, and keep the fortune in the family."

"I! Marry that girl who hypnotized an old woman into leaving her a fortune! You're crazy. Besides, I am married."

"You haven't caught your aunt's ideas on divorce, have you? You don't feel tied to that woman who ran away with that French Count, do you? You divorced her, didn't you? You—"

"Hold everything! We were talking of the Reyburn girl. You have nerve to make the suggestion that I marry her. Men have been put on the spot for less. I wouldn't marry that schemer if—"

Brooke flung back the hanging in a passion of rage.

"Nobody asked you to!" She cleared her voice of hoarseness, and flamed:

"Has it never occurred to you, Mark Trent—" She stopped, her eyes wide with amazement. Was this really the man who had pulled her from in front of that speeding car? After the first flash there was no recognition in his eyes, nor any concern, rather a quiet mockery, which, she felt, at the first word of hers would turn into active dislike.

"You! You—" Her breath caught in a laugh that was half sob. "What a mean break for you that you didn't know who I was, that you didn't let that car hit me! Then you would have had the money."

She had never seen a face so colorless as Mark Trent's as his eyes met hers steadily.

"Lucky I didn't know who you were, wasn't it? I might have been tempted. Schemers somehow lead charmed lives."

For a split second Brooke thought that fury had paralyzed her tongue. She made two attempts to speak before she protested angrily:

"I'm not a schemer! I suppose it never has occurred to you that the 'Reyburn girl' may have loved Mary Amanda Dane? May have been glad to spend one evening a week in a homey old house away from her whole 'darn family' in a crowded city apartment?"

Failure of breath alone stopped Brooke's tirade. There was plenty more she could say, she was apt to be good when she started. A laugh twitched at her lips. The two men facing her couldn't have looked more stunned when she made her theatrical entrance had a hold-up man with leveled gun suddenly stepped from behind the hanging. So this was Mark Trent. She had been careful never to go to Lookout House when he was there, for fear that he might think she had planned to meet him, and then he had gone to South America. Mrs. Mary Amanda Dane had had no photographs of him about. Once she had spoken of his youth, of his prowess in football, tennis, and his election as Class Day marshal, and his promotion to head a large insurance business, and then bitterly of his marriage and divorce.

In reporting her Lookout House visits to the family upon her return, she had referred always to Mrs. Dane's nephew as Mark the Magnificent, with a spicy twist to her voice which had delighted her audience. But she had not realized that he would be so bronzed nor so tall, that his dark eyes were so uncompromising, nor that the set of his mouth and chin could be so indomitable. There was a fiery, strong quality of life in him which sent prickles of excitement like red-hot slivers shooting through her veins. She knew now that she should have appeared from behind that hanging at Jed Stewart's first word.

Stewart's always ruddy face was the color of a fully grown beet. He coughed apologetically.

"Sorry, Miss Reyburn. Didn't know you'd come. I'll slit the throat of that secretary of mine for not telling me. So you two have met before? That's a coincidence."

"No coincidence about it, Jed. Apparently we were both on the way to this office to keep an appointment with you, when we 'met' in the street almost in front of this building."

Brooke's anger flared again at Mark Trent's cool explanation. She met the terrier brightness of Jed Stewart's gray-green eyes. She had liked him when she had come to his office in response to the Court's amazing notification that she was residuary legatee under the will of Mary Amanda Dane. The black and white check of his suit accentuated the rotundity of his body. He puffed out his lips as he regarded her with boyish entreaty. She laughed.

"The present uncomfortable situation only goes to prove, doesn't it, Mr. Stewart, that listeners never hear any good of themselves? Though really I wasn't listening. I stepped behind the hanging to look at the marvelous view, and then—"

"You heard Jed say that your hair was like copper with the sun on it, and—"

"I stuffed my fingers in my ears for a while, but I heard a lot more, a whole lot more," Brooke cut in on Mark Trent's sarcastic reminder, "before I heard you refuse to marry me."

"But that was before I had seen you." The suavity of his voice brought hot tears of fury to her eyes. Before she could rally a caustic retort, he picked up his hat.

"That's a bully exit line. I'll be seeing you, Jed. Hope you'll enjoy the house and the fortune, Miss Reyburn. Happy landings!" He laughed. "I'd better say, 'Safe landings!' You're such a reckless person."

"Hi! Fella!"

With an impatient jerk, Mark Trent shook off the hand on his sleeve, rammed his soft hat over one eye, and closed the door smartly behind him. Stewart relieved his feelings in an explosive sigh and pulled forward a chair.

"That seems to be that. Sit down, Miss Reyburn, while I tell you about the allowance which will be made you while Mrs. Dane's estate is being settled."

II

From the lighted stage Brooke Reyburn looked into the auditorium of the department store in which she had worked for four years. She had begun by modeling sports clothes, and because she had loved her work and had given it all the enthusiasm and drive there was in her she had been promoted steadily. The first of this last year she had been made head fashion adviser and had been sent to Paris. She had made frequent trips to New York, but never before had she been abroad. Now she was talking for the last time to a hall full of women, many of whom she had come to know by sight. She had given her last radio talk. It was the end of her business career. What would the new life bring her?

Even as she thought these things, she told her audience that the silver frock the lovely blonde on the stage was modeling was a copy of Chanel, called attention to its touch of theatre; that the smart black tailleur she herself was wearing was from the Misses Better Dress Shop at $29.50; that neither brown as a color nor gold jewelry should be worn by the grey-haired woman; that a questionnaire had brought out the amusing fact that the majority of married men liked to see their wives in blue; asked if the ravishing scent she was spraying from the atomizer was reaching them—one dollar a dram at the perfume bar—and said for the last time in closing:

"This concludes our fashion show. Thank you."

As she stepped from the stage, Madame Céleste, the autocratic head of the store's department of clothes for women, stopped her. Her figure was a restrained thirty-six; her black frock was as chic as only a Lanvin model could be; the pearls at her ears were the size of able-bodied marbles; her make-up would have done marvelous things for a younger woman, for her it achieved nothing short of a miracle. A hint of emotion warmed the hard blue of her eyes as she caught Brooke's hands.

"Cherie," her French was slightly denatured by a down-east twang, "I shall lose my right hand when you go. Why did that meddlesome old party want to butt in and leave you money? You were on the way to making it here."

"I shall miss you, Madame Céleste." Brooke's voice was none too steady.

"Perhaps you won't have to long. In this here-today-and-gone-tomorrow age, money doesn't stay in one pocket. Remember, cherie, whenever you want a job, come to me. You'll be needing one. Au revoir!"

"Cheering thought that I may lose the fortune," Brooke reflected, as she approached her office across the hall. Suddenly the black letters:

MISS REYBURN

on the ground-glass panel of the door jiggled fantastically.

She blinked moisture from her lashes—she hadn't supposed she would feel choky about leaving. She opened the door, closed it quickly behind her, and backed against it as a man slid to his feet from the corner of her desk. His black hair shone like the coat of a sleek well-brushed pony; his dark eyes were quizzically amused as they met hers; his teeth were beautifully white; he was correctly turned out in spic and span business clothes. He was likable, but there was something missing—rather curious that never before had she felt it. He lacked—he lacked salt, Brooke decided, and then reproached herself for being critical. He had been marvelously kind to her, and she was quite outside his social circle—now, she would not have been during her father's lifetime.

"How's tricks?" he inquired gaily.

"How did you get in here, Jerry Field?"

"Easy as rolling off a log. A taxi, an elevator, a few strides on shanks mare, and here I am."

"I've told you time and again not to come to my office."

"While you were on the job, you said, sweet thing. I've stayed away and all the time the old wolf jealousy gnawed at my heart. I've imagined you here entertaining the male heads of departments and letting them, or stopping them, make love to you."

"You've been seeing too many movies. I shall drop fathoms in your estimation when I tell you that no man in the organization has ever been otherwise than friendly and helpful. Perhaps I'm not a glamorous person, perhaps I haven't the divine spark which touches off the male imagination."

"Perhaps it's because they know that those corking eyes of yours look straight into their minds. We're wasting time. You are through, and here I am all in a dither to take you teaing and stepping and dining to celebrate your entrance into the land of the free."

"Nice of you but—I wonder how free I shall be."

Brooke crossed her arms on the back of a chair and looked about the office. She would miss it, miss even the display figure in the corner with its red polka dotted cheeks and staring eyes. There had been hectic moments when she had talked out her problems to its wax immobility. Her glance came back to the man watching her.

"How long is it since you and I first met, Jerry?"

He drew a memoranda book from his pocket and consulted its pages.

"Six months, one week, and six days."

"Foolish! Pretending you have it in black and white."

He tapped the closely lined page. "Believe it or not, there it is, the date when you and I spent an hour trapped in an elevator which wouldn't move. You were coming from a radio talk and I from a conference with my broker who had informed me that my account was figuring exclusively in the red. Fate, sweet thing, fate."

"Fate! The starter told me it was a balky cog. It was an experience I hope never to repeat, even if it brought you and me together. I was frightened."

"But you laughed. That's what got me, your sportsmanship, and when you clutched at my coat it was like fingers on my heart."

Brooke turned quickly to the closet. She must switch him from that track. As she took down her short lapin jacket and slipped into it, she said lightly:

"How you dramatize life. You have been miscast. Instead of being born a rich man's son and spending your days dabbling in paint and the stock market, you should be on the stage. With your flair for good theatre, you'd be packing them in. Perhaps Sam can get you a chance in his company. Have you seen the play in which he is acting?" she asked with a quick change from lightness to gravity.

"Yes. Your brother's good."

"But you don't like the play?"

"I can't hand it much."

"Neither can I. It's a dummy with not a breath of life, not a drop of red blood, just clever epigrams and stuffed-shirt characters. I wish Sam hadn't been cast in it."

"Don't worry. It won't last long. What's the next play on the stock list?"

"The Tempest. The apartment rings with, 'Bestir! Bestir! Heigh my hearts! Cheerily, cheerily my hearts!'"

"You're not bad yourself, Brooke. Why didn't you take to acting?"

"I ought to be good. We children were raised on dramatics and quotations. It was Father's habit to orate when he was shaving, and we could spout Shakespeare before we could spell. Besides being a publisher, he was a playwright for amateurs, but Sam is ambitious to write for the professional stage; he has one three-act comedy finished, that is, as finished as a play can be until it is put into rehearsal. That is why he is acting, that he may know all there is to know of stage technic. I've had theatre enough in my late job. Late! I can't believe that I'm through. Come on, Jerry, before I sob on the shoulder of that display figure."

"Lot you'll sob on that when I'm here." He patted his shoulder and grinned engagingly. "This one is warranted sound, kind, and a corking tear-absorber."

"I'll wager my next week's salary that it is damp from constant use. Let's go. I asked the girls not to come to say good-bye as if I were going away forever. They gave me a grand farewell party last night, and I have perfume, hosiery, and bags enough to last the rest of my natural life. Go ahead. I want to snap out the light myself."

As she stopped on the threshold, Jerry Field caught her arm.

"Hey, no looking back. Remember what happened to Lot's wife. I'd make a hit, wouldn't I, tugging a pillar of salt round the dance floor." He shut the door smartly behind them.

Brooke blinked and swallowed. "Okay, Jerry, from now on I go straight ahead like an army with banners, but straight ahead doesn't mean teaing and dancing with you tonight."

When they reached the already darkening street, Jerry Field demanded:

"Why won't you go stepping with me now?"

"Because I am going home to plan with the family about moving, and to plot the curve of our domestic future."

"Look here, Brooke, don't persist in that silly idea of living in the house Mrs. Dane left you. It's all right for spring and summer, but what will you do marooned on a rocky point of land almost entirely surrounded by water when the days get short, in a place where the residents dig in and nothing ever happens? The causeway which connects the peninsula with the mainland sometimes is submerged in a storm. Suppose we have one of our typical New England winters?"

Brooke had thought of that. She loved living in the city, loved this time of day and this time of year when the shops glittered with lights, when the smell of roasting chestnuts seeped from glowing braziers on corners, when the streets were jammed with traffic and every person in the crowd hurried as if he or she had somewhere to go and were on the way. She drew a long breath of the keen October air and let it go in a sigh.

"It is a charming old house, Jerry. I shall love it. I'm a business woman on the outside and a home-maker at heart. I hear that many of the residents who usually summer there are planning to keep their homes open and live in them this winter—it's a trend—so perhaps something will happen, something exciting, on that peninsula of land you scorn. These are the melodramatic thirties, remember. It will be rather thrilling to go into an absolutely new environment; an adventure in living. One never can tell what's waiting to pounce as one turns the corner. Twenty miles isn't far from town."

"It's twenty miles too far. If you were here in the city, I could pick you up in a minute and we could go places. To date you've handed out the excuse that you were too busy. People are planning to winter there, are they? That's an idea. You won't lose the fortune if you don't live in the old place, will you? It wasn't a condition?"

They were walking toward the crimson and jade sunset against which a huge electric clock seemed colorless.

"No. Mrs. Dane merely left a note with her lawyer, in which she wrote that she wished I would live there for two years, or at least until I had cleared the house of her belongings, that she knew that I would not laugh at her treasures, that I would understand, and that I would care for her parrot, Mr. Micawber. That parrot leaves me cold, Jerry. So you see, I must live in the house for a while—now that the lordly Mark Trent has given permission. I—"

"What has Mark Trent to say about it?"

Brooke looked up in surprise as they waited for the traffic light at the corner to change to red and yellow.

"Don't bite. Do you know him, Jerry?"

"Sure, I know him."

"Why haven't you told me?"

"Why should I? I'd forgotten that he was Mrs. Dane's nephew who had been cut off with a shilling or less."

She caught his arm. "Look out! Wait for the light! I had that lesson seared into my mind last week—and ground into my knee," she added to herself.

"Now we can go. You must have been excited to start to walk in front of a car. Why do you dislike Mark Trent?"

"Don't dislike him. Just don't want to think about the man, that's all. My sister Daphne went cockeyed about him and he turned her down hard. Like a perfect gentleman, of course, but it got my goat."

Brooke visualized Mark Trent as he had glared down at her on the street, and later as she had seen him in Jed Stewart's office. She couldn't imagine him changing his mind when once he had determined on a line of action. He looked like a man who knew exactly what he wanted and was out to get it. Even the memory of him sent little prickles along her veins.

"Are you sure he turned her down?"

"Sure. I'm not blaming him, I'm ashamed for her, that's all. He was probably fed up with her type. His ex-wife was never quite sober, I've heard. Daphne fell for him the minute she saw him, she had worried me by her crazy ideas of freedom for a girl, she'd picked up a post-war germ somewhere—all talk of course—and when Trent came along, she stopped drinking and staying out till morning at Night Clubs. I was relieved. Then he side-stepped. Forget it. I don't know why I told you. Nice street this, isn't it?"

Brooke nodded assent as they passed houses whose polished windows, violet-paned some of them, screened by laces of unbelievable fineness, regarded her with inscrutable calm. Thoroughbred dogs, proudly conscious of their gay collars and smart breast-straps, decorously escorted their young masters. Shining limousines waited before charming old doors. In the distance rose the faint, far sound of traffic, murmurous as a mighty flood which never rolled nearer.

"Here we are at your door. Sure you won't change your mind and go stepping?" The boyish quality was back in Field's voice. "Grand old house. Pity it was turned into apartments. Do you realize that you never have invited me to meet the family? What's wrong? Ashamed of your home—or me?"

"Neither. What a beastly suggestion, Jerry. If you must know, I haven't told them about our friendship. I have the finest family in the world, but their bump of humor is over-developed, it isn't a bump, it's a coconut."

"What is there about me that's a joke?"

"Nothing; don't be so touchy. I decided to be a little mysterious, that's all. Sam resents it if I ask him a question about his friends, thinks I am treating him like a boy when he is almost two years older than I; and since I got Lucette the chance to model and she is financially independent, she scorns my interest."

"Is your mother like that?"

"No, Mother's a dear, but she is so bound up in her children that she has no real life of her own. It's a pity because she is a comparatively young woman."

"She sounds old-fashioned and motherly to me. Grade A in mothers. I like that kind. Can't I come in and meet her? I had planned to celebrate with you. Now that you've turned me down, I haven't any place to go."

"You carry off that aggrieved, little-boy pose well, Jerry, but it leaves me cold. You, with your Crowd—capital C—, having nowhere to go! That's the funniest thing I ever heard. I intend to devote the next two hours to making plans with the family. It's hard to get hold of Sam, but he promised to stay at home until he had to go to the theatre."

"How soon do you take to the sticks?"

"I'm going down tomorrow to look over the house, my half of it, though it isn't a half, it's a whole twin. A week ago Mr. Stewart told me what I might spend to make it livable—it's a dangerous concession, he doesn't know my spending capacity. It has been on leash so long that I tremble to think what will happen when I loose it. I'll take one gorgeous crack at extravagance."

"Is that guy doling out money to you? Isn't it yours?"

"Not for a year. He could hold it up if he wanted to, but, as Mark the Magnificent—that's what we call him in the family councils—is the only legal heir and as he won't contest the will,—I wanted him to take half of the property or a third even, but he turned me down hard—it is safe to give me an allowance. When we are settled, I will invite you to Lookout House. Good-night, Jerry."

As she waited in the hall for the elevator to descend, Brooke thought of Jerry Field's question:

"Ashamed of your home—or of me?"

She certainly was not ashamed of her home. The apartment might be small and crowded, but there were many fine pieces of maple and mahogany and the family portraits were choice, but no choicer than the family itself. This change of fortune would change her outwardly. It would free her real self, the impetuous self whose impulse was to help, to be hospitable. She had had so little money since her father's death that the old bogey, FUTURE, had jogged her elbow whenever her fingers started toward her purse. She must remember always what it meant to have little. People were so apt to forget when they became prosperous, so apt to become slightly contemptuous of those who were struggling to make ends meet. She had seen it happen a number of times. She would be much happier if Mark Trent had a share of the money, but he must know how bitter his aunt had been about him. Probably that was the reason he wouldn't touch it.

The front door slammed with a force which shook the house. Sam, of course. The atmosphere tingled when he appeared. He was whistling as usual. Good-looking boy! His horn-rimmed spectacles added a touch of distinction. She patted his sleeve as he stopped beside her.

"Had a nice day, Sammy?"

"Not too good. They're taking off the play tomorrow. Our dear public wouldn't see it."

He pulled open the elevator door. "Hop in." As it clanged shut, he asked:

"All through being a working girl?"

Brooke swallowed a lump in her throat and nodded.

"It will seem queer being a lady of leisure."

"Leisure! You don't know the first letter of the word. I can see you wondering what you'll do next. Leisure isn't your line. You'll plunge into classes and sports. There won't be hours enough in a day for you."

The elevator stopped. A voice seeped through the cracks around the apartment door. Sam Reyburn grinned.

"Say, listen! Lucette's on the air—and how."

"Oh dear, what's her grievance now?" Brooke whispered, and put her key into the lock.

She tried to appraise with the eyes of a stranger the high-ceilinged, large living-room she entered. A connoisseur of portraits would know that Grandfather Reyburn over the mantel had been painted by a great artist; that the portrait of his daughter on the opposite wall was a choice bit of work; that the Duchess of Argyle in her sables, green satin, and emeralds was a masterpiece. Always she had wanted to decorate a room as a background for the picture. Now she could. The Duchess was hers. The mahogany and maple was sadly in need of rubbing up, but no amount of wear and tear could disguise its period and value.

Her eyes lingered on her mother perched on the arm of a couch. She did young things like that. Her hair was a sheeny platinum; her eyes were dark; her skin was clear and smooth; her figure in the amethyst crêpe frock was round without in the least suggesting fat. There was a quizzical twist to her lovely mouth as she looked at her younger daughter, who, with legs thrust straight out before her, was slumped in a chair. Her red beret, which matched the belt of her slim green plaid frock, was on the floor. Her hair was black and wavy; her eyes were brilliantly dark; her painted lips drooped at the corners. Brooke recognized the symptoms. Sam had been right, Lucette was on the air. She said as she slipped out of her lapin coat:

"In the Valley of Despond again, Lucette? Had a nice day, Mother?"

Mrs. Reyburn smiled and nodded. She would make her home-coming children think she had had a nice day, if the heavens had fallen. She was like that. Lucette answered her question.

"You'd be in the Valley of Despond, if you had had the day I've had, Brooke Reyburn. I'm dead to the world. A woman came into the sports shop with three daughters, and kept me showing clothes all the afternoon. Gosh! My feet ache like teeth gone nervy."

"Did she buy much?"

"Not that baby. She bought that little blue number only. For Pete's sake, why does Sam have to whistle when he's under the shower? The walls of this apartment are regular sounding boards."

"Bear up, Lucette, you will be out of it soon. If we can't sublet this apartment, we'll shut it up."

"Spoken like a lady and a multi, Brooke darling. And after that what?"

"You won't have to model for fussy women and you'll have a dressing room of your very own. Mr. Stewart has told me that I may take possession of Lookout House as soon as I like. Mark the Magnificent has given the Jovian nod. He won't contest the will. I'm going there tomorrow with a plumber. A bath for every bed will be my battle-cry."

Silence followed her words, a silence fraught with significance. Brooke caught her sister's look at her mother before she sat up straight and tense. She knew that posture, she was preparing for a skirmish. Lucette said defiantly:

"Glad you brought up that subject, Brooke. News flash! I'm not going to the sticks with you, not if you offer me a gold tub with diamond settings. I spent one night at the home of the late Mary Amanda Dane, and, so far as I am concerned, the name means look out and not go there again. That sealed door in her living-room gave me the creeps. I kept thinking, 'What's on the other side?' for all the world like Alice when she wonders what goes on in Looking-Glass house. There might be bodies concealed there or loot, it has been shut up so long. No thanks! I'm all for the city. 800,000 residents can't be wrong. Sam isn't—"

She dashed to the hall as the telephone rang.

"Lucette Reyburn speaking," she answered eagerly.

"Yes—yes—he is. I'll call him." Her voice was as flat as de-bubbled champagne. She pounded on the bath-room door.

"Phone for you, Sam.—How do I know? It's the girl who always calls just as you've stepped under the shower.—All right."

She returned to the phone. "Hold the line. He'll be here in a minute."