4,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: BookRix

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

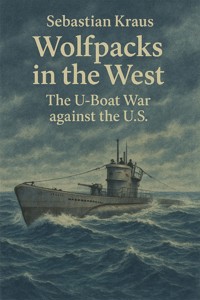

Wolfpacks in the West: The U-Boat War against the U.S.

An untold chapter of World War II unfolds beneath the waves of the Atlantic…

In early 1942, as America reeled from the shock of Pearl Harbor, a new and deadly threat emerged just off its shores. German U-boats—lethal, stealthy, and commanded by some of the Kriegsmarine’s most skilled officers—launched a devastating submarine campaign against the United States. From the icy waters of Newfoundland to the warm currents of the Gulf of America, coastal cities burned, tankers exploded, and merchant seamen vanished into the deep.

Wolfpacks in the West tells the gripping and meticulously researched story of the German U-boat war against the U.S. homeland—an often-overlooked theater of the Battle of the Atlantic. Through 40 rich, immersive chapters, the book explores daring patrols by elite German crews, the chaos and complacency of early American defenses, the brutal evolution of anti-submarine warfare, and the human cost on both sides of the periscope.

Drawing on wartime records, survivor accounts, declassified intelligence, and modern underwater archaeology, this narrative brings to life not just the battles, but the strategies, innovations, and shifting tides that shaped one of the most dangerous campaigns of the Second World War. From Enigma codes and hunter-killer groups to sunken wrecks and postwar reconciliation, this is a sweeping chronicle of courage, tragedy, and transformation.

A tribute to sailors above and below the waves, Wolfpacks in the West is a must-read for anyone interested in naval history, WWII, or the power of the sea to both divide and unite.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Ähnliche

Wolfpacks in the West

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Kapitel 1:Chapter 1: The Seeds of War Beneath the Sea

Kapitel 2: Chapter 2: Kriegsmarine Strategy and the Role of U-Boats

Kapitel 3: Chapter 3: America Before Pearl Harbor: An Unprepared Coastline

Kapitel 4: Chapter 4: The Atlantic Wall Begins at Sea

Kapitel 5: Chapter 5: Building the U-Boat Arm: Training, Tactics, and Technology

Kapitel 6: Chapter 6: Type VII and IX – The Workhorses of the Deep

Kapitel 7: Chapter 7: Orders from Berlin – The Launch of Operation Paukenschlag

Kapitel 8: Chapter 8: First Strike – U-123 off New York

Kapitel 9: Chapter 9: Nightmares in Norfolk – U-Boat Successes Multiply

Kapitel 10: Chapter 10: Blackout Failure – America’s Vulnerable Shoreline

Kapitel 11: Chapter 11: The Toll of Inexperience – U.S. Naval Unreadiness

Kapitel 12: Chapter 12: U-66 and the Tanker Terrors

Kapitel 13 : Chapter 13: Shadows at the Surface – Merchant Ships Under Fire

Kapitel 14 : Chapter 14: From Florida to Halifax – U-Boats Range Freely

Kapitel 15: Chapter 15: The Caribbean Convoys and the Battle for Oil

Kapitel 16: Chapter 16: The Gulf of America – A New Hunting Ground

Kapitel 17: Chapter 17: Sinking Liberty – The Cost in American Lives and Ships

Kapitel 18: Chapter 18: Axis Allies – Italian Submarines Join the Fight

Kapitel 19: Chapter 19: Fear in the Homeland – American Public Reactions

Kapitel 20: Chapter 20: Turning the Tide – The Formation of the Eastern Sea Frontier

Kapitel 21: Chapter 21: Convoys Return – Lessons from Britain Applied Late

Kapitel 22: Chapter 22: ASW Technology – From Huff-Duff to Hedgehog

Kapitel 23: Chapter 23: Aircraft Patrols and Coastal Defense

Kapitel 24: Chapter 24: The Secret War: Intelligence, Enigma, and Codebreaking

Kapitel 25: Chapter 25: Training the Submarine Killers: U.S. Destroyers Rise

Kapitel 26: Chapter 26: The Role of the Civil Air Patrol

Kapitel 27: Chapter 27: The Second Wave: Renewed U-Boat Offensives in 1943

Kapitel 28: Chapter 28: Wolves in the Sargasso: Tactics and Adaptations

Kapitel 29: Chapter 29: Lone Wolves and Group Hunts: Changing Strategies

Kapitel 30: Chapter 30: Weather, Fuel, and Survival – The Harsh Realities for U-Boat Crews

Kapitel 31: Chapter 31: The Fate of the Hunters – Sinking of U-Boat Aces

Kapitel 32: Chapter 32: American Counterintelligence and Saboteurs from the Sea

Kapitel 33: Chapter 33: The Balance Shifts – Losses Mount for the U-Bootwaffe

Kapitel 34: Chapter 34: The Bay of Biscay Gauntlet

Kapitel 35: Chapter 35: U-Boats Trapped and Tracked

Kapitel 36: Chapter 36: Victory in the Atlantic – The End Nears for the Grey Wolves

Kapitel 37: Chapter 37: May 1945 – The Last Boats Surrender

Kapitel 38: Chapter 38: The Human Cost – Sailors on Both Sides

Kapitel 39: Chapter 39: Wrecks Beneath the Waves – Archaeology of the Atlantic War

Kapitel 40: Chapter 40: From Enemies to Allies – Remembering the U-Boat War in America

Kapitel 1:Chapter 1: The Seeds of War Beneath the Sea

The story of the U-Boat war off the American coast does not begin with torpedoes striking tankers under moonlight or steel hulls slipping silently through the waves. It begins decades earlier, in the slow accumulation of strategic thought, technological innovation, and bitter memory. The seeds of underwater warfare between Germany and the United States were sown in the First World War, nurtured by resentment, refined through doctrine, and ultimately catalyzed by the ideological and geopolitical cataclysm of the Second World War.

To understand the U-Boat war of the 1940s, one must first look back to its predecessor—the First Battle of the Atlantic. During World War I, German U-Boats waged an aggressive campaign of unrestricted submarine warfare, attempting to cut Britain off from vital supplies by sinking merchant shipping faster than it could be replaced. In 1917 alone, U-Boats sank nearly 6 million tons of Allied and neutral shipping.

The United States, initially neutral, found itself increasingly drawn into the conflict by repeated attacks on American vessels. The 1915 sinking of the RMS Lusitania, killing 128 Americans, shocked the public. By 1917, Germany’s decision to resume unrestricted submarine warfare was a key factor in pushing the United States into war. Submarines had forever changed naval strategy. They were no longer seen as mere coastal defenders or torpedo boats but as strategic weapons that could strike from the shadows and choke nations into submission.

Yet, the war ended with the defeat of Germany and the dismantling of its once-proud navy. The Treaty of Versailles not only restricted the number of ships Germany could possess but explicitly forbade it from maintaining a submarine fleet. But treaties, like surface fleets, can be circumvented—and memories of past success, even in defeat, have a long half-life.

In the wake of the Treaty of Versailles, the German Navy (now the Reichsmarine) was a ghost of its former self. However, even during the Weimar Republic years, there were efforts—some clandestine, others theoretical—to preserve and advance submarine knowledge. German naval officers worked with Soviet and Scandinavian counterparts to test torpedoes and designs, while German engineers found employment abroad, particularly in the Netherlands and Spain, building the very submarines they could not legally design at home.

With the rise of Adolf Hitler in 1933 and the creation of the Kriegsmarine, Germany began a rapid rearmament program, openly flouting the Versailles restrictions. By 1935, Germany had signed a naval agreement with Britain allowing for submarine construction at 45% parity with the Royal Navy. The seeds were now germinating in the open. The U-Boat fleet was officially reborn.

The architect of the Kriegsmarine’s early doctrine was Grand Admiral Erich Raeder, a traditionalist who still favored battleships and surface action groups. But in the ranks of the officer corps, a younger generation saw things differently. Chief among them was Karl Dönitz, a former U-Boat commander from the Great War and a fierce advocate for submarine warfare. Dönitz would go on to become Befehlshaber der Unterseeboote (BdU)—Commander of Submarines—and eventually Grand Admiral himself. He was convinced that Germany’s best hope for victory at sea lay beneath the waves.

Dönitz was a meticulous and cerebral leader who understood the limitations of German naval strength. Unlike Britain and the United States, which could draw upon vast global resources and massive shipbuilding capabilities, Germany would never be able to match their enemies ship for ship. But Dönitz did not intend to fight such a war.

Instead, he developed the tactic of Rudeltaktik—or wolfpack warfare. Rather than sending out lone submarines to stalk merchant ships, he envisioned coordinated groups of U-Boats, vectored toward convoys via radio signals from listening posts and U-Boat patrols. Once in range, these packs would attack en masse, overwhelming convoy defenses in synchronized strikes, usually at night and on the surface, where U-Boats were faster and more agile.

To Dönitz, the U-Boat was not a tactical nuisance but a strategic weapon of economic warfare. His calculations were simple: if German submarines could sink more Allied tonnage than could be replaced—estimated at around 700,000 tons per month—Britain and her allies would eventually collapse under the weight of starvation and logistical strangulation.

This doctrine would shape the coming war, and nowhere would it prove more disruptive, more surprising, or more terrifying than off the shores of the United States.

Across the Atlantic, the United States was emerging from the Great Depression with a cautious optimism and a deeply rooted sense of isolationism. After World War I, the prevailing sentiment was to avoid foreign entanglements. This national mood found expression in the Neutrality Acts of the 1930s, which sought to keep America out of European conflicts.

The U.S. Navy, once a proud force, had languished somewhat during the interwar years. Naval budgets were constrained, and strategic thinking was largely focused on the Pacific and potential conflict with Japan. The Atlantic fleet, though not neglected, was under-resourced compared to the rising threat in Europe.

But even isolationism had its limits. As the war clouds darkened over Europe in the late 1930s, President Franklin D. Roosevelt began quietly preparing for a conflict that many Americans still hoped to avoid. The Naval Expansion Act of 1938 and the Two-Ocean Navy Act of 1940 were massive steps toward rebuilding naval power, including anti-submarine vessels and technologies. Yet, by the time of Pearl Harbor, much of this buildup remained incomplete. When Germany turned its U-Boats westward in 1942, the U.S. eastern seaboard was not ready.

Dönitz saw the American coastline as a ripe target. Hundreds of unescorted merchant ships, lit against the glow of coastal cities, sailed in plain sight. Ports such as New York, Norfolk, and Charleston were bustling with traffic, much of it bound for Britain and the Soviet Union. The U.S. Navy was stretched thin, its escort fleets underdeveloped, its anti-submarine doctrine still in its infancy.

It was the perfect environment for the U-Boat war to evolve from an Atlantic struggle into a transcontinental campaign. What had begun in the cold North Atlantic would now spread like oil on water to the warm, shallow seas of the Gulf, the Caribbean, and the eastern seaboard.

By the end of 1941, the stage was set. The U-Boats were armed, the doctrine tested, and the targets numerous. Germany had found its weapon, America its vulnerability. The seeds planted in the muddy trenches of 1917 and the secret naval yards of the 1930s were about to bear their most lethal fruit.

The Battle of the Atlantic was about to shift westward—and for the first time since the War of 1812, enemy warships would stalk American waters.

Kapitel 2: Chapter 2: Kriegsmarine Strategy and the Role of U-Boats

The story of Germany’s naval war in the Atlantic is often told in terms of daring submarine patrols, hunted convoys, and the grim dance between U-Boats and destroyers. But beneath the surface warfare lay a strategic doctrine carefully shaped by political constraints, economic realities, and a naval command forced to reconcile ambition with harsh limitations. The Kriegsmarine—Hitler’s navy—was born into a world where the surface was dominated by the British Royal Navy. It was beneath that surface that Germany sought its best chance of breaking the enemy’s will.

Following Adolf Hitler's rise to power in 1933, Germany rearmed rapidly, including the rebuilding of its navy. Yet from the outset, the Kriegsmarine operated under a severe handicap: time. Germany had neither the resources nor the industrial capacity in the 1930s to challenge Britain and France on the seas, and certainly not the United States. The Z Plan, formulated in 1939, was the brainchild of Grand Admiral Erich Raeder, and envisioned the construction of a balanced battle fleet—featuring aircraft carriers, battleships, heavy cruisers, and a substantial U-Boat arm—by 1948.

This plan reflected traditional Mahanian thinking: that sea power was best expressed through capital ships and control of maritime chokepoints. Raeder, a product of the Imperial Navy, clung to the surface fleet ideal. But the outbreak of war in September 1939 rendered the Z Plan obsolete. The Kriegsmarine had to go to war with the fleet it had—not the one it dreamed of.

At the start of hostilities, the Kriegsmarine’s order of battle was modest. It possessed only two operational battleships—Scharnhorst and Gneisenau—a handful of cruisers and destroyers, and roughly 57 operational U-Boats, many of them coastal models with limited range. Against the Royal Navy’s vast surface fleet and the growing U.S. Navy, this was not a navy built for supremacy. It was a navy designed to disrupt.

Within the naval hierarchy, a philosophical divide began to take shape. While Raeder continued to support a surface fleet strategy, his subordinate, Karl Dönitz, was developing an entirely different vision.

Dönitz believed in economic warfare. His strategy did not seek to win by naval engagements in the traditional sense, but to cripple Britain’s war-making ability by severing its maritime supply lines. He viewed merchant ships as the soft underbelly of Allied logistics. The U-Boat, cheap to produce and crew, could exploit that vulnerability.

Dönitz’s idea was not new—it had been proven in World War I—but he refined it into a coherent doctrine. In Dönitz’s estimation, Germany needed 300 ocean-going U-Boats to carry out an effective tonnage war against Britain. This number was based on calculations involving convoy sizes, U-Boat availability, operational tempo, and expected losses. However, at the outbreak of war, he had only a sixth of that number.

Raeder, although skeptical of Dönitz’s claims, did not obstruct U-Boat construction. But priority was divided. Resources flowed into surface vessels like the heavy cruisers Admiral Hipper and Prinz Eugen, and the famed battleship Bismarck. It wasn’t until these ships were lost or rendered ineffective that Hitler and Raeder began to reconsider Dönitz’s submarine-centric strategy.

Adolf Hitler had little affinity for naval matters. His strategic thinking was deeply continental and focused primarily on Eastern Europe. To him, the navy was always a secondary concern. He viewed surface ships with skepticism after the Graf Spee and Bismarck incidents demonstrated their vulnerability.

However, the U-Boat campaign intrigued him. It was a weapon that could strike silently and economically. It appealed to his taste for asymmetric warfare—cost-effective, psychological, and devastating. Though not always consistent, Hitler gradually warmed to Dönitz’s vision, especially as German surface losses mounted and Britain remained resilient.

In early 1943, after Raeder's resignation, Hitler promoted Dönitz to Oberbefehlshaber der Kriegsmarine (Commander-in-Chief of the Navy). For the first time, the Kriegsmarine was led by a man who saw the war beneath the sea as Germany’s most viable path to maritime success.

The U-Boat served five core strategic purposes in Kriegsmarine doctrine:

Economic Warfare – The primary objective was to cut Britain off from its sources of supply. If Britain could not import food, oil, and materiel, it would eventually collapse economically and politically.

Psychological Pressure – The U-Boats were intended not only to inflict material damage, but to instill fear. The image of invisible killers lurking off the coast, threatening any ship at any time, was a powerful tool of psychological warfare.

Resource Diversion – U-Boats forced the Allies to divert massive amounts of resources into convoy protection, anti-submarine warfare (ASW) technologies, and naval construction. Every destroyer or aircraft carrier built for convoy duty was one less for the Pacific or other theaters.

Disruption of Strategic Timetables – Delaying American and British logistics caused ripple effects across the Allied war effort. Missed convoy schedules could delay offensives, starve frontlines, or leave critical industrial centers understocked.

Intelligence and Reconnaissance – U-Boats also served as scouts, tracking convoys and feeding information back to command centers in Lorient, Brest, or Wilhelmshaven. They gathered weather data crucial for Luftwaffe operations and assessed Allied naval deployments.

U-Boats were, by their very nature, flexible. Unlike surface ships, they did not need ports in foreign lands to exert pressure. Once supplied with torpedoes, food, and fuel, a Type IX U-Boat could operate for 70 to 90 days, ranging as far as the U.S. eastern seaboard, the Caribbean, and even the coast of Brazil. Refueling at sea by so-called “Milchkuh” submarines (Type XIV) extended that range even further.

This flexibility allowed Germany to strike unpredictably. One month, U-Boats could be attacking convoys off Iceland; the next, they could be sinking tankers in the Gulf of America. This operational mobility was crucial in the early war years, when Allied ASW doctrine was still rudimentary.

The Atlantic was vast—stretching over 3,000 miles. The “air gap” in the mid-Atlantic meant that for a long time, no land-based aircraft could patrol those waters, leaving convoys vulnerable. The U-Boats took full advantage of this, striking from the deep and disappearing before retaliation could arrive.

Despite their theoretical advantage, the U-Boat force was never able to reach the numbers Dönitz had originally calculated as necessary for victory. German industry, already stretched by the needs of the Army and Luftwaffe, struggled to meet submarine production quotas.

Furthermore, the Kriegsmarine invested heavily in technological improvements, some of which would come too late to change the outcome of the war. Innovations like the Schnorchel (snorkel), improved acoustic torpedoes, and the Type XXI Elektroboot—a revolutionary new submarine design—were all developed under pressure, but few reached the front in time to alter the course of the conflict.

By contrast, the Allies, especially the United States, ramped up escort ship and merchant vessel production at a staggering pace. The advent of the Liberty Ship, built in mere weeks, meant that tonnage sunk by U-Boats was increasingly replaced faster than it could be destroyed.

By early 1942, the Kriegsmarine’s strategy shifted more aggressively toward the Western Hemisphere. With Britain still standing and the United States now fully at war, Dönitz launched Operation Paukenschlag (Drumbeat), targeting the poorly defended American coastline. It was the culmination of his long-held belief in the strategic value of the U-Boat—and the beginning of a new phase in the Atlantic war.

The success of the early 1942 U-Boat offensives validated Dönitz’s doctrine, at least temporarily. But the seeds of the U-Boat force's eventual decline were already visible: insufficient numbers, evolving Allied tactics, and the inability to innovate faster than the enemy.

The Kriegsmarine’s strategy—shaped by necessity, vision, and constraint—elevated the U-Boat from a tactical platform to a strategic weapon. For a time, this undersea fleet seemed capable of turning the tide of the war, threatening to starve Britain and delay America's full mobilization.

But the U-Boat campaign, while brilliant in conception and daring in execution, was ultimately undermined by the very factors it was meant to exploit: overextension, Allied resilience, and the march of industrial war. Still, its influence reshaped modern naval warfare—and left a deep scar on the American shoreline.

The stage was now fully set. In the next chapter of this undersea war, the wolfpacks would move west—into waters few believed would ever run red with German steel.

Kapitel 3: Chapter 3: America Before Pearl Harbor: An Unprepared Coastline

In the years leading up to December 1941, the United States stood astride a continent, rich in natural resources, untouched by the scars of war, and protected by two vast oceans. Yet beneath this illusion of safety, the eastern seaboard—stretching from Maine to the Florida Keys—was a soft underbelly, a vulnerable artery upon which the nation’s economic heartbeat depended. In 1941, the American coastline was a corridor of light, commerce, and complacency. It was also, unbeknownst to most, a battlefield in waiting.

The dominant political sentiment in the U.S. during the interwar years was isolationism—a profound reluctance to become entangled in European wars. Haunted by the losses of World War I and disillusioned with European politics, many Americans believed the Atlantic Ocean was a sufficient buffer against any foreign threat. This conviction was reinforced by the Neutrality Acts of the 1930s, which restricted arms sales, loans, and American involvement in overseas conflicts.

The geography of the continent gave further comfort. The U.S. Navy and coastal authorities assumed that any direct threat would come with ample warning, and that the Navy, with its growing fleet of capital ships, would intercept enemies far from the shores. Few considered that submarines—small, stealthy, and able to operate independently—could exploit this false sense of security.

This belief in safety translated into strategic neglect. In early 1941, the U.S. eastern seaboard had no comprehensive anti-submarine plan. There were insufficient patrol vessels, outdated sonar systems, and, most critically, a complete lack of convoy protection for merchant shipping operating in domestic waters.

In 1941, the eastern seaboard was the economic engine of the United States. From the bustling ports of New York, Philadelphia, and Norfolk, goods and oil flowed both domestically and across the Atlantic to Britain and its allies. Major oil refineries, munition plants, and shipyards were concentrated along this coast, making it a hub of industrial activity—and a lucrative target.

Yet even as tensions with Germany escalated in the Atlantic, few precautions were taken. Coastal cities continued to shine brightly at night, casting silhouettes of outbound merchant ships against illuminated skylines—perfect targets for lurking U-Boats. Streetlights, billboards, amusement parks, and boardwalk hotels all remained fully lit well into 1942.

German U-Boat commanders would later describe the American coastline as a “shooting gallery,” with tankers and freighters outlined like clay pigeons on a glowing horizon. One U-Boat captain, Reinhard Hardegen of U-123, would famously remark: “It was as though they didn’t know there was a war on.”

Despite increasing cooperation with Britain through the Lend-Lease Act and Destroyers for Bases Agreement, the U.S. Navy in 1941 was unprepared for large-scale submarine warfare close to home. Its doctrine remained heavily influenced by traditional fleet actions, focused on battleships and carrier groups.

The Atlantic Fleet, under Admiral Ernest King, was still in transition. Anti-submarine warfare (ASW) was poorly prioritized. Many destroyers lacked effective sonar (ASDIC) or depth charge capabilities. Escort carriers and long-range patrol aircraft were still in short supply.

Responsibility for coastal defense was split among several agencies:

The U.S. Navy oversaw high-seas operations and some harbor defenses.

The U.S. Coast Guard handled coastal patrols and port security but was underfunded and poorly equipped.

The Army Air Corps had few aircraft suited for maritime patrol and lacked coordination with naval forces.

The Merchant Marine operated in a civilian capacity with no real protection until mid-1942.

The lack of centralized command and effective inter-service communication left the coastline dangerously exposed.

While German U-Boats utilized advanced torpedoes, encrypted communications (via Enigma), and wolfpack coordination, the United States lagged behind in several key areas:

Sonar (ASDIC): American sonar systems were often unreliable and poorly deployed. Many ships lacked them entirely.

Radar: Still in its infancy, early U.S. shipboard radar was rare and mostly ineffective for submarine detection.

Aircraft Range: Patrol bombers like the B-24 Liberator were not yet deployed in large numbers, and the infamous “Atlantic Gap” remained unguarded by air.

Tactically, the U.S. Navy still operated under the assumption that coastal waters were too shallow for U-Boat operations. They underestimated the Type VII and Type IX submarines’ ability to maneuver in tight areas, often just miles offshore.

The practice of unescorted sailing was the greatest doctrinal failure. While Britain had adopted the convoy system as early as 1939, the U.S. continued to send merchant vessels out individually, trusting that the sheer size of the Atlantic would offer protection. It did not.

Another major weakness was the lack of intelligence coordination. British codebreakers at Bletchley Park were beginning to crack some levels of the German naval Enigma system by mid-1941, but this information was tightly held. American cryptography efforts were still developing and had not yet reached the level of real-time naval intelligence.

Additionally, while the Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) was aware of U-Boat activities in the North Atlantic, it underestimated the likelihood of near-shore attacks on U.S. territory. Reports from British liaison officers warning of a potential U-Boat campaign off the American coast were often met with skepticism or bureaucratic delay.

The Germans, meanwhile, were listening. Using signals intelligence and intercepted radio traffic, they mapped shipping routes, port activity, and American naval patterns. When Dönitz initiated Operation Paukenschlag in January 1942, he did so with an intimate understanding of the chaos and inexperience he would face.

The general public remained largely unaware of the threat lurking offshore. Newspaper coverage of the U-Boat menace was minimal in 1941, often censored or softened to avoid panic. Civil defense was still focused on air raids and sabotage—not maritime attack.

When merchant ships began vanishing without explanation, it took time before local authorities even considered submarine activity. In some coastal areas, oil slicks, floating wreckage, and even survivors were dismissed as accidents rather than acts of war.

Politically, Washington was focused on larger diplomatic and military challenges: preparing for possible war with Japan, aiding Britain and the Soviet Union, and navigating a volatile domestic climate. The idea that enemy submarines would one day be sinking ships within sight of Atlantic City, Cape Hatteras, or Miami Beach seemed fantastical—until it happened.

In fact, Germany had already begun probing American waters before Pearl Harbor. In 1941, several U-Boats operated in the mid-Atlantic and even off the Canadian coast. U-203, U-123, and U-66 shadowed convoys and relayed positions back to headquarters in Lorient. German naval intelligence gathered weather data and ocean current patterns from neutral shipping reports and radio intercepts.

There were hints of what was coming, but they were ignored.

In September 1941, USS Greer exchanged depth charges with U-652, an event President Roosevelt used to justify the "shoot-on-sight" policy for German vessels. Two months later, USS Reuben James was sunk by U-552 in the North Atlantic—killing over 100 American sailors.

Despite these warnings, American shipping along the coast remained defenseless.

In the final weeks before Pearl Harbor, America stood on the brink of global war—armed with industrial power, manpower, and raw potential, but blinded by assumption. The coastline, lined with tankers and freighters, was undefended. The civilian population, shielded by false peace, was unprepared. And the U.S. Navy, stretched thin across two oceans, was about to face a new and insidious threat—one not of aircraft or fleets, but of steel sharks hunting in shallow waters.

The hour was late. The coast was open. The wolfpacks were coming.

Kapitel 4: Chapter 4: The Atlantic Wall Begins at Sea

Before the Allies ever stormed the beaches of Normandy or faced down concrete bunkers and Flak batteries along Europe’s western coast, there was already an Atlantic Wall—one not built of steel and concrete, but of silent predators patrolling the ocean depths. The Kriegsmarine's strategic vision, long before the physical wall was erected in France, extended seaward—into a vast, three-dimensional battlefield where U-Boats would form a mobile, fluid, and lethal line of defense and offense.

This "wall at sea" would become the first line of resistance in Hitler's effort to isolate Britain, starve it into submission, and prevent American supplies and soldiers from crossing the Atlantic unscathed. It was a wall built not to hold ground, but to deny access, disrupt logistics, and create terror on the high seas.

The term “Atlantic Wall” would later be associated with the imposing defenses of Occupied France, Belgium, and the Netherlands—an elaborate system of bunkers, gun emplacements, and minefields along the coast. But in 1940, long before that term was formalized, the Kriegsmarine understood that the true battlefield began at sea. If Britain was to be isolated, and if America was to be kept from reinforcing Europe, then the Atlantic Ocean itself had to become a killing field.

This thinking aligned with Dönitz’s core doctrine: destroy the lifeline between the New World and the Old. Without American oil, steel, grain, trucks, and war materiel, Britain could not survive. And if the United States could not cross the Atlantic, it could not fight.

Thus, Germany’s first Atlantic Wall was not a coastal fortification—it was a strategic U-Boat barrier, stretching from the icy seas off Greenland down to the warm waters of the Azores, and eventually reaching the Gulf of America and Caribbean. Unlike the Maginot Line of World War I, this wall could shift, evolve, and adapt. It was invisible but deadly.

Key to this strategy was the establishment of massive U-Boat bases along the occupied French coast after the fall of France in June 1940. These ports—Lorient, Brest, St. Nazaire, La Rochelle, and Bordeaux—became the operational nerve centers of the U-Bootwaffe.

From these bases, U-Boats could access the open Atlantic within hours, bypassing the narrow and dangerous route through the North Sea. These Atlantic ports were quickly fortified with reinforced concrete pens—massive bomb-proof shelters that could house and service entire flotillas. Some of these pens had roofs over 7 meters thick, impervious even to the largest Allied bombs of the early war years.

Each base served a different function:

Lorient: The operational headquarters for Karl Dönitz, and home to the 2nd and 10th U-Boat Flotillas.

Brest: A launching point for long-range patrols into the central and western Atlantic.

St. Nazaire: A critical maintenance and resupply hub, supported by naval workshops.

La Pallice (La Rochelle): A base for Type IX boats operating in the South Atlantic and beyond.

Bordeaux: Home of the Monsoon Group, later tasked with U-Boat operations as far as the Indian Ocean.

These fortress ports formed the static anchor points of the Atlantic wall at sea. From here, the Kriegsmarine extended its reach across the ocean with waves of submarines.

Unlike fixed artillery on land, the U-Boat fleet provided a mobile defensive barrier. Dönitz’s signature tactic—the Rudeltaktik or wolfpack strategy—enabled groups of U-Boats to patrol in loosely coordinated lines across known convoy routes.

Each U-Boat in a patrol line was spaced approximately 20–30 kilometers apart. When one boat sighted a convoy, it would report its location via encrypted signal and shadow the target until reinforcements could arrive. Then, often under cover of night, the pack would strike in coordinated waves, overwhelming escort ships and decimating merchant vessels.

This tactic transformed the ocean into a dynamic combat zone. No sea lane was truly safe. Merchant ships could be attacked hundreds of miles from land, with no warning. This capability made the U-Boat force not just an offensive weapon, but a strategic barrier to Allied movement.

By mid-1941, these patrol lines had been established along the following critical corridors:

North Atlantic Convoy Routes: From Halifax to Liverpool.

Mid-Atlantic Gap: The “Black Pit” beyond the range of Allied air cover.

Southern Approaches to Britain: Near Gibraltar and the Azores.

Greenland-Iceland-UK (GIUK) Gap: A natural chokepoint for northbound convoys.

This fluid network of kill zones became the maritime expression of a modern “wall”—always shifting, but always deadly.

To maintain this vast mobile defense line, the Kriegsmarine relied on the Enigma machine, a complex cipher device used to transmit operational orders to and from submarines. With Enigma, Dönitz’s command center in Lorient could direct U-Boats across thousands of kilometers with relative security—at least until the British began to crack the code.

Enigma allowed for:

Dynamic rerouting of boats to intercept convoys.