14,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

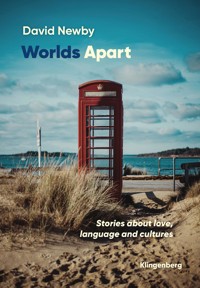

- Herausgeber: Verlag Klingenberg

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

‘Worlds Apart’ is about relationships between men and women from different places, different languages, different national cultures, different religions, different lifestyles, and of course, different genders. The stories are humorous yet heart‐rending, satirical yet sensitive, upsetting yet uplifting – essential reading for anyone who loves life, language and British humour.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 263

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

The Birds Trilogy:

Teaching Birds to Talk

Teaching Birds to Sing

Teaching Birds to Fly

Culture Lovers

Carol’s Christmas

Joy of Man’s Desiring

Framing

The Reading Circle

About the author

Editorial

Lascia la spina, cogli la rosa

Grasp the rose and leave the thorn alone

– Georg Friedrich Händel

Teaching Birds to Talk

I’ve got this budgerigar at home. Name’s Penny. And she’s a talker. They say that female budgerigars can’t talk. But this one can. Just like a woman. ‘My name’s Penny,’ she’ll say, ‘What’s yours?’ And lots of other things besides. It took me months to teach her. When I think of the hours I’ve sat by that cage repeating over and over again: ‘My name’s Penny, my name’s Penny’ till I was blue in the face. For a long time she just used to sit there staring at me as if to say: ‘Tha’s bonkers, lad!’ That’s what me two mates Arnold and Terry in the Pig in the Poke used to say too.

‘Tha’s bonkers, Cyril! Female budgies don’t talk. Everyone knows that.’

Then one day – I can remember it as clear as a bell – I was just putting me boots on to go off to the Pig in the Poke, when suddenly she shouts out: ‘My name’s Penny – what’s yours? My name’s Penny – what’s yours?’ over and over again as if her very life depended on it. Do you know, I was so happy when I heard that, I nearly burst into tears. I don’t think I’ve ever been so happy in my life. Well, perhaps the first few weeks with Natalya. But that’s all water under the bridge now.

Course it’s not really talking. Just sounds. At least that’s what Natalya used to say. I wonder if she knows what she’s saying. I wonder if birds can think. Sometimes I just sit next to her cage gazing at her for hours and she gazes at me and I think, ‘I wonder what she’s thinking.’ ‘Penny for your thoughts, Penny.’ That’s what I say to her. And she says it back to me: ‘Penny for your thoughts, Penny.’ I suppose if it was real talking, she’d say ‘Penny for your thoughts, Cyril.’

I made no secret of the fact that I got Natalya from a marriage bureau. The owner had got the photos all laid out in neat little rows on his desk. Reminded me of the rows of bird cages it did, when I went to buy Penny. Come to think of it, he probably said more or less what the pet shop owner said.

‘Now Mr Stanley, which of these young ladies takes your fancy?’ It was hard to tell. I mean, it wasn’t just me fancy she was going to take, it was the rest of me life, half of me bungalow, half of me bathroom, half of me bed. She was going to be coming with me to the saloon bar of the Pig in the Poke. It was much more than me fancy.

‘It’s hard to say from just a photo,’ I said. ‘This one looks presentable enough, but I’d like to have a chat with her.’

‘Ah, Mr Stanley,’ he said, ‘a chat would cause something of a problem with regard to her present location. At this precise moment in time she is not residing in the immediate vicinity.’

‘You mean, she’s not in Yorkshire?’ I said.

‘No,’ he replied, ‘she’s not in Yorkshire, she’s in Minsk.’

‘Where’s Minsk?’ I said.

‘Minsk! You don’t know Minsk! Minsk is but a short plane ride from Leeds Airport.’

And Leeds Airport is but a short car ride from my bungalow. But the marriage bureau man didn’t want me to fetch her in person. Said he would deliver her to my door. We’d done all the paper work and the financial aspects the night before so when he brought Natalya, he dropped her at the garden gate with her belongings and was off without so much as a by-your-leave. She stood there at the gate, looking nervous. Right bonnie lass. Quite a bit younger than me. Tall, high-jumper’s legs, squarish jaw, pretty eyes that slanted at the corners. Duty free plastic bag from Minsk Airport with half a bottle of Johnny Walker. My present. I rushed outside and took her little canvas bag off her. Touch of the gentleman like.

‘Hello, love,’ I said. ‘Have you had a good trip? Come on in and I’ll make you a nice cup of tea. Coronation Street’s just started if you like the telly.’

She didn’t move. Just stared at me, like I was mad or something. Then I noticed her eyes darting back and forward like she was trying to think of something. All of a sudden she grabbed my hand and shook it hard. Then she said in a slow and loud voice that reminded me of one of them James Bond spy films:

‘Good day. My name is Natalya. What is yours?’

I’ve got to laugh when I think back to them first few days. I must admit I was bit shocked to discover that she could hardly speak a word of English, let alone Yorkshire. It was all miming and play acting at the beginning. We got quite good at that. Had quite a laugh. Good way to break the ice, I suppose. Patting me stomach and throwing out me arms to ask if she was hungry. Pointing at Penny and making little jerky movements with me fingers to tell her that Penny could talk. When she wanted to know where the toilet was and tried to mime that, we laughed so much I thought we were going to bust a gut. I had to take out me hanky and wipe the tears from her cheek. And when it came to bed time and we had to – well, you know, resolve the sleeping arrangements – it all went like a dream. I must say I hadn’t been looking forward to broaching the subject, knew I’d be a bit embarrassed about clarifying the details, but somehow it was easier to ask about it without having to talk about it. Just felt real natural like. Afterwards, in bed, she really opened up – spoke a lot to me. Course, it was all in Russian or whatever they speak in Minsk. But it didn’t matter. I knew what she was saying even if I couldn’t understand a word. I just felt so incredibly happy. Like a little baby.

The next day I began to teach her to talk. I thought, well if it worked on Penny it can work on Natalya too. So as soon as we’d had our breakfast, I began with lesson one. Started with the really important things for her, like vacuum cleaner and washing-up liquid and self-raising flour. She was a real quick learner. After a couple of days she could say quite a lot. When she’d learnt some new words she liked to try them out on Penny. She would go over to her cage and say:

‘Penny, my name is vacuum cleaner. What is yours?’

It’s funny, though. Penny would never talk to her. The moment Natalya came into the room, she’d go all silent. Almost as if she was jealous. Another funny thing was that Natalya didn’t seem to like Penny much either. Would never let her fly around the living room and couldn’t stand it when I talked to her. One day, when I was trying to teach Penny to say ‘give us a kiss’ she shouted out:

‘Penny she not talk. That not talk. Penny not want nothing. She live in cage. She not real talker. My talk is real talk.’

I hadn’t got the faintest idea what she meant, but I suppose her English wasn’t up to much at that stage so she was a bit confused in her thinking.

She loved going down to the pub in the evening. Much preferred that to the telly. I think it was being with Arnold and Terry. She seemed to like male company. They liked her too. She said being there was good for her English. Never stopped asking questions: easy ones, like ‘what means “pint”?’, which we could all answer, and hard ones, like ‘when you say “some” and when you say “any”?’, where none of us had the faintest idea what she was talking about. Sometimes ones that made us laugh, like when she asked Arnold what ‘haemorrhoids’ meant and he went bright red. One night, as we were coming away from the Pig in the Poke, she looked up at the pub sign and pointed to the picture of the pig. Can’t say I’d ever really noticed it before but when she saw it, her eyes lit up like a little child.

‘Cyril,’ she says: ‘please tell me what is “poke”. What means “pig in a poke”?’ ‘Oh dear, love,’ I said. ‘You’ve got me there. I mean, it’s an expression you hear all the time, but I couldn’t actually tell you what it means.’

She began to laugh – them gorgeous slit eyes spread out and made her look really mischievous.

‘Cyril,’ she says, ‘I think you not speaking English very good.’

I must say, I felt a bit embarrassed about that.

‘You’ll have to ask that young chap across the road,’ I said. ‘He teaches at the further education college. Go and knock on his door some time.’

I was quite glad when she started going to the college. She really thrived on it and always came home really happy. And as for her English, well it improved beyond all recognition. She was really pleased about that but to be honest I preferred how she spoke before. I know that might sound a bit daft, but you see because she had learnt all her talking from me, she sort of talked like me. What I said, she said. All those little sayings of mine that me mother used to laugh at when she was still alive, like ‘I’ll be back in two shakes of a lamb’s tail’ when I went to the pub or ‘the bird has flown’ when someone left the house. And because she talked like me, I reckoned that she thought like me too. We sort of spoke the same language if you see what I mean. But after a couple of evening classes at that college she began to use strange words, words that didn’t belong in my bungalow, like ‘exquisite’ – that was the first one I noticed. Then there was ‘perverse’ and ‘presumptuous’ and ‘repugnant’ and ‘exonerate’ – a whole host of words like that. Course, I knew what they meant but it was obvious she hadn’t got them from me. I would never have used them myself. What really got me was ‘crème de la crème’. After that I just couldn’t keep up with her any more. One night she came home and said:

‘Cyril, I have just been enlightened with regard to the meaning of “pig in a poke”.’

‘Well, miss clever-knickers,’ I said, ‘in that case you can enlighten me and Penny too.’

She lifted that square chin of hers quite high as she had taken to doing recently. ‘Your beloved Natalya was a pig in a poke,’ she said. ‘That’s what you got when you chose me.’ Those slit eyes of hers gave a little flash.

One evening, just before Christmas, I heard her going out of the front door. ‘The bird has flown,’ I thought to myself as I usually did when she went out. It struck me as strange that she hadn’t come into the living room to say good-bye so I called out:

‘Where are you off to?’

‘Can’t stop to talk,’ she shouted back, ‘I’ll be back in two shakes of a lamb’s tail. I must fly or I’ll be late.’

That was the last thing I ever heard her say. Never saw her again. Didn’t bother to tell the police. That college lecturer across the road disappeared too. So I put two and two together.

Now that Natalya has gone, at least I can devote more time to Penny. It seems to me that she’s started to talk much more recently. I suppose I could start letting her out of the cage again now – let her fly round the living room. She used to love that. But somehow I just don’t want to take the risk. It would only take one open window and she’d be off and away.

Teaching Birds to Sing

‘Tell me I am music in your ears. The apple of your eye. The gilt on your gingerbread. Your crème de la crème.’

These were Natalya’s first words as I carried her across the threshold into our new flat. I had to admit that her English was remarkable: she was not just a walking dictionary, she was a walking thesaurus.

‘I couldn’t have put it better myself,’ I replied.

‘No, Mr. college lecturer,’ said Natalya, ‘you couldn’t have put it better yourself,’ to which she footnoted a smile of what I was later to recognise as rueful condescension but thought at the time was affection.

If truth be known, I had been rather apprehensive about living with Natalya. It was a big jump from secret trysts in my single bed after evening classes to sharing a household, but we quickly fell into a conjugal pattern, dictated largely by Natalya. I didn’t mind that. I had never been one to take responsibility.

From the beginning it was clear that she would not be content with the role of a housewife.

‘There’s more to life than vacuum cleaners or self-raising flour,’ she proclaimed when she first saw the kitchen.

A few days later, she announced triumphantly that she had got a job at the information desk in the university library.

‘How did you manage that?’ I asked.

‘Surely you must have realised by now, my dear Adrian, that men cannot resist my persuasive rhetoric, not to mention my sexy foreign accent.’

She quickly made friends with the library staff and had soon become an oracle whom students and lecturers, mainly male, it seemed, would consult in droves. She liked the company of other people – more than the company of me, I sometimes thought. She also liked reading and would come home with a bagful of novels tucked under her arm, which she would read until the early hours of the morning. She was particularly interested in female characters and would want to discuss them with me. Sometimes she would shake me awake in the middle of the night with a question:

‘Adrian, which adjectives best describe Tess of the D’Urbervilles: “passionate”, “headstrong”, “contrary”, “capricious”, “whimsical”, “resolute” …?’

‘It’s hard to say,’ I muttered sleepily – anaesthetised, no doubt, by the overdose of adjectives being force-fed to me.

‘My dear Adrian, nothing is hard to say,’ she replied. ‘You just have to move your tongue and your lips.’

Frustrated, no doubt, by my inability to engage in literary debate, she joined, and dragged me along to, a reading circle of university people, in which she would express strident, and non-negotiable, views.

‘Mr Darcy is rich and handsome. Elizabeth gets a big house and servants: a perfect life if you ask me. Why bother being a feminist if life treats you so kindly?’

Such comments were usually met with culture-sensitive, patronising silence: no one wanted to impose their liberal western attitudes on this noble savage from beyond the Balkans or the Caucasus or the Urals or wherever they thought Minsk might be. But one literary character seemed to baffle her:

‘This Lucy in Room with a View; she says she finds it hard to understand people who speak the truth. What does she mean by that?’

‘Welcome to England,’ whispered a bearded academic, barely audible.

To divert her attention away from the university set and towards me, I tried to interest her in what was one of my passions – birdwatching. But she seemed not to get the point of it. Once when we were huddled together behind a tree watching a marsh harrier flapping over the reeds, she said:

‘You English do strange things with birds. You either lock them up in cages and force them to talk or you transfix them with binoculars and tick them off your lists as if they were your property. Why can’t you just let them sing and fly?’

She would often make this type of pugnacious, final-word statement, which made me feel like a cornered rat with nowhere to go.

Natalya was a beautiful singer. She would always sing in Russian – folk songs, I presumed – while washing up and cleaning the kitchen, chores she would never let me take part in.

‘These are womanly things,’ she would say. ‘Go and do some manly things like chopping wood or shooting a few pigeons.’

What was I supposed to say to that, I wondered.

Yesterday, when we were walking through the woods, we heard a cuckoo sing.

‘What a beautiful song!’ I said to Natalya.

‘You call that a song? Are you serious?’ she replied, knitting her eyebrows, and fixing me with a laser beam stare, which, I had come to realise to my cost, indicated imminent confrontation. ‘In my language we say that bird is calling, not singing. Singing is what I do, and very beautifully too, as you have often told me.’

‘Cuckoos are one of my favourite birds,’ I ventured, wondering if her knitted eyebrows would parry my comment. And so they did.

‘Your favourite bird? What do you like about them: the fact that they can’t be bothered to build their own nests? You like how they force other birds to bring up their baby – I believe it is what you English call cuckolding, is it not? You like how the baby cuckoo kills its stepbrothers and sisters?’

I didn’t reply. This was one of her favourite tactics during arguments: to provide me with multiple-choice boxes to tick off, all of which expressed her opinion and none of which expressed mine.

‘Say something, Adrian,’ said Natalya.

‘I suppose you’re right,’ I said, while thinking that she was wrong but unable to find words to support my view.

At my suggestion, we joined a choir. I had heard that St. Stephen’s church was in need of volunteers. They didn’t seem to mind that we were not religious. At least, I thought we weren’t, but Natalya would not enter the church without her hair being covered with a floral headscarf and she would always cross herself with vigour. The choirmaster showed particular enthusiasm on hearing that Natalya was Russian – ‘Belorussian,’ she corrected in vain; he clearly thought that her ethnicity would ‘uncover layers of musical mystery’, as if he were a child opening up his first babushka doll.

‘We shall be looking to dear Natalya to inject a little cocktail of passion into our staid Anglican ways,’ he announced to a sceptical, ageing, Anglo-Saxon choir.

And so Natalya did. From the first piercing note that she emitted, it was clear that she would sing in the Russian style: each note was pitched slightly above that sung by the other sopranos and was of an amplitude which exceeded that of the choir as a whole. At the first rehearsal, the other members appeared to find this mode exotic, and smiled; at the second, they found it irritating, and frowned; at the third they found it unacceptable, and sighed. However much they sought to focus on their ‘wings of a dove’ or ‘nymphs and shepherds’, Natalya’s voice was a constant musical tinnitus that could never quite be ignored. With rapidly diminishing Anglican tact and patience, the choirmaster attempted to re-assemble and re-seal the babushka doll.

Natalya should ‘rein in her voice,’ he suggested.

‘I am a singer, not a horse!’ she protested.

‘My dear, we should sound as one voice,’ he exhorted.

‘Does not singing with one voice rather make nonsense of the concept of a choir, Mr choirmaster?’ she retorted.

‘Natalya, you must adapt to the conventions of an English church choir and try to sing more like us,’ he insisted.

‘Why don’t you try and sing more like me?’ she persisted; ‘what was all that about injecting a cocktail of passion?’

‘If I may say so, I think there is rather too much vodka in the cocktail,’ he countered.

But Natalya was not one to be out-metaphored.

‘If I may say so, I think there is rather too much milk in your tepid tea,’ she replied.

And with that, she stormed down the aisle and out through the door, pausing only to drape her floral scarf over the choirmaster’s bald pate.

I was never really sure whether Natalya was happy living with me. I got the impression that I did not really come up to her expectations. At one point, she had invented what she called the ‘lexicon game’: a competition whose aim it was to come up with adjectives to describe someone we knew, or a television personality or a politician. Of course, she always won every game and would conclude each one with a disdainful comment: ‘I must say, Adrian, I don’t think you speak English very well’ would be the bluntest. Once, when she had gone out, I played the game alone and listed some adjectives about myself – as I imagined Natalya saw me. But I soon stopped when I realised that all the words I had chosen were negative: ‘taciturn’, ‘truculent’, ‘morose’, ‘irresolute’, even ‘repugnant’ had crossed her lips in recent days to describe me.

As I arrived home from college yesterday, the front door of our house opened when I was half way up the garden path. Natalya stood there filling the door frame, hands on hips, high jumper’s legs splayed, square jaw thrust forward as if she were about to fend off an intruder.

‘I’ve got some good news,’ she said, her slit eyes a-twinkle. ‘I’m pregnant. Come on in,’ she said pulling at my hand, ‘there’s a bottle of champagne in the fridge.’

‘Any reaction, Mr Englishman,’ she asked as we clinked glasses.

‘To be honest,’ I replied, ‘I think I’m lost for words.’

‘Oh no, my dear Adrian,’ she retorted, ‘you’re not lost for words, you’re lost for emotions.’

‘Well, it’s come as a bit of a shock.’

‘If being told that you are about to become a father is a bit of a shock, then you’ve led an exceedingly charmed life. If you want to know what a real shock is, remind me to tell you about my childhood some time.’

Another of her ‘final word’ statements. But this time I did have something to say.

‘Are you sure you want to keep the baby?’ I ventured.

‘I’m already in my fifth month,’ she countered. ‘It’s too late for that. By the way, it’s a girl. I had a scan today.’

‘But why didn’t you tell me earlier?’ I asked. Natalya gave a mischievous smile, but didn’t answer.

‘Have some more champagne,’ she said as she filled up my glass to the brim.

I couldn’t sleep a wink last night. I’d been doing a bit of calculating …

* * *

I knew Adrian was sulking. When he had a lot on his mind, he had nothing on his lips. I’m sure he didn’t sleep a wink last night.

‘I’ve been thinking,’ he said, quite unnecessarily. ‘And I’ve been doing a bit of calculating. I mean, if the baby is due in September, then you got pregnant before you … you know…’

‘Slept with you, made love to you, had sex with you,’ I interrupted, giving him a palette of synonyms to choose from.

‘Yes,’ he stammered. ‘So that means that … well, that I’m not the father. It’s Cyril.’

‘Brilliant, Mr Mastermind!’ I said. ‘Is that a problem? We’ll never tell Cyril. We’ll be a family – you and me and the baby girl.’

‘But it’ll be like … you know, like having a cuckoo’s egg in our nest.’

‘Are not cuckoo’s your favourite bird?’ I replied.

He seemed to want to say something. But he didn’t.

There was something different about the flat when I got home from work that evening. Adrian was nowhere to be seen. His coat was not on the hanger and his slippers weren’t next to the hearth.

‘The bird has flown,’ I thought to myself.

The note he had left was typewritten. I must say that he was better at expressing himself in writing than face to face. Nicely composed letter, with some impressive synonyms: he felt we were not compatible, that we did not see eye-to-eye, that we did not speak the same language, that we were not singing from the same hymn sheet.

Instead of a forwarding address, he left an old Cream Cracker tin with bundles of twenty-pound notes in it. Later I counted them on the kitchen table to see how much he thought my services had been worth. If I’d been a whore, he wouldn’t have got off so cheaply. But I wasn’t.

For a while I stood outside the pub before I went in. The Pig in a Poke sign creaked rhythmically in the evening breeze. Arnold and Terry were in their usual seats, half-empty pints of bitter in front of them.

‘Just look what the cat’s brought in!’ said Arnold.

‘Well knock me down with a feather!’ said Terry.

They averted their gaze. Terry looked at the floor, Arnold at the ceiling.

‘I was looking for Cyril,’ I whispered.

‘Cyril doesn’t come here any more,’ said Terry.

‘He prefers to stay at home,’ said Arnold.

‘With Penny,’ said Terry.

‘I have some news to tell him.’

‘That’s not a very good idea,’ said Terry.

‘I reckon tha should leave him be,’ said Arnold.

So I did.

I didn’t really care that Adrian had gone. He had become increasingly taciturn and morose and irresolute. I would be better off without him. In any case, I wouldn’t be lonely: I had my job at the library; I had my reading circle; I had the Orthodox church in Leeds, which I had begun to attend. But best of all I had my baby girl to look forward to. And in a few months’ time I would be singing her the Russian lullabies my mother used to sing to me.

Teaching Birds to Fly

‘Mum, I’m home. And I’m starving!’

This was her daily mantra when she got home from school. I suppose teenage girls always are hungry. Hormones, or something. When I was a teenager, I was hungry because there was hardly anything to eat.

‘I’m in the kitchen, Olga, I’ve made you some bliny!’

‘Not that Russian stuff again,’ she groaned as she pushed open the kitchen door. ‘I want some real food.’

When she was a child, she loved that ‘Russian stuff’. She loved everything that was Russian: the lullabies, the frilly dresses and floral scarves, the celebrations at the Orthodox church in Leeds, and – it’s hard to imagine it now – she loved speaking Russian, the language of her mother, the language of my mother, the language of my beloved grandmother. But that all stopped as soon as she started secondary school.

‘Govorit po-russki!’ I would say a thousand times.

‘Why should I? Your English is even better than my English teacher’s,’ was a typical response. She had acquired a multiple-choice set of arguments against speaking Russian which left me without a leg to stand on.

‘But it’s your mother tongue,’ I would plead.

‘But not my father’s tongue,’ she once said. I could have told her how pitiful and primitive and impoverished her father’s language actually was, but the only information I had chosen to divulge about him was that he was called Cyril and – a white lie – that he did not reside in the immediate vicinity and was probably dead. When she was at primary school, I began to teach her to read and write in Russian. ‘This is the Cyrillic alphabet,’ I said, ‘founded by St. Cyril in the 9th century.’

‘St. Cyril!’ she said, ‘just like my dad!’

‘Perish the thought!’ I said.

Olga and I have always enjoyed a harmonious relationship. Since I was of a young age when she was born, it was as if she were the younger sister I never had. We saw eye-to-eye on most things; I think she regarded me as her role model.

‘You are my dependable oracle, always to be consulted,’ she once said to me. She, like me, would switch to English when making grand pronouncements, for which both of us have a propensity. Her English was music in my ears; it is, or used to be, of an exceptional nature which set her apart from her school peers. This strengthened the bond between us: because she spoke like me, I knew that she thought like me. Or so it was, until certain men came on the scene and dragged her language and her life down into their gutter.

Being a single mother with a full-time job at the university, I rued and resented not being able to devote my full attention to her: never once did I drop her off at nursery school without fearing that my little crème de la crème, as I called her, might be soured. But once my novel was published, I was able to give up work and devote all my time to her. Sometimes, I missed the hubbub of the university: the fawning students, the flirtatious men, my somewhat anodyne acquaintances from the reading circle, so eager to drink from the fount of knowledge I provided. Of course, I could have remained in the reading circle, but it seemed that the other members were intimidated into silence by being in the presence of a best-selling author. Or so I assumed.

‘Chopping wood and shooting pigeons’: that was what the novel was called. The main protagonist was a humble forester from Belorussia called Vladimir, who lives in a country village and whose life is transformed when an intellectual Russian family from St. Petersburg arrives for a holiday in the country and proceeds to educate the ‘noble savage’ – as the Sunday Times called him – by reading Tolstoy and Pushkin to him, and in the case of the three sisters, by serially seducing him in the cherry orchard. There were lots of literary allusions, idioms and – my special trademark – ‘a rampant roller-coaster of adjectives’ (The Guardian), which pleased the critics, and lots of au naturel sex under cherry trees, beeches and poplars, which kept readers turning the pages. With reluctance, I published the novel under a nom-de-plume. I would have liked fame as well as fortune, but opted for a certain degree of anonymity: I didn’t want people delving into my past life. For Olga’s sake, there were things that were better kept in the dark.

* * *

It’s sort of weird that even though me and mum are so close, I don’t know much about her past life. I know she had a really rotten childhood in Minsk, wherever that is. Dad drank himself to death, mum was abroad the whole time – cleaning the lavatories of rich German women, was how she put it. She was looked after by her gran, her babushka, and only saw her mum in the summer holidays. When she was 14, her mum just stopped coming back and stopped sending money home, so her babushka couldn’t support her. I think she was 18 when she came to England.

‘How did you manage to scrape together enough money for the flight?’ I once asked her.

‘Where there’s a will, there’s a way,’ she replied.