Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

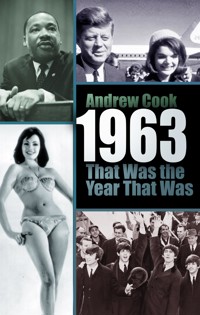

While we conveniently package the past into decades when talking about the 'Roaring '20s', 'the Rock and Roll era' of the '50s or the 'Swinging '60s', these tend to be labels of convenience rather than of historical accuracy. In reality, the first four years of the 1950s were more akin to the 1940s, with austerity and rationing still facts of every-day life. Likewise, the first three years of the '60s were, in terms of fashion, social attitudes and living standards, really part of the 1950s. The year 1963 was to be the seminal year when most of the things we now associate with the 'Swinging '60s' really began. Most years are fortunate to experience three or four seminal events during their allotted twelve months; a cursory look through a chronology of 1963, however, shows just how many significant events took place. This year alone saw a huge number of watershed moments in popular culture, national and international politics. Arranged in a chronological, month-by-month format, 1963: That Was the Year That Was pieces together these happenings, exploring their immediate and long-term effects and implications. This is a fascinating read for both those who lived through these momentous times, and those who want to learn more about the start of the swinging '60s.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 311

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

About the Author

Andrew Cook is a historian, author and TV consultant. He has written for The Times, The Guardian, The Independent, BBC History Magazine, History Today magazine, and was a consultant for the ‘MI6 – The Official History of the Secret Intelligence Service 1909–1949’ project. His previous fourteen books include Sidney Reilly: On His Majesty’s Secret Service (2002), Ace of Spies (2003), M: MI5’s First Spymaster (2005), To Kill Rasputin (2005), Prince Eddy (2006), Cash for Honours (2008), The Great Train Robbery: The Untold Story from the Closed Investigation Files (2013), and No Case to Answer: The Men Who Got Away with the Great Train Robbery (2022).

He has acted as a consultant on twenty-one TV documentaries, produced by the BBC, Channel 4, Channel 5 and History Channel since 2004, and three TV dramas, based on his books.

andrewcook.org.uk

In memory of my fatherand the walk on Wardown Lake

Front cover, clockwise from top: Martin Luther King, 26 March 1964 (Marion S. Trikosko/Wikimedia Commons); President Kennedy and Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, 22 November 1963 (Wikimedia Commons); The Beatles visit America, Kennedy Airport 7 February 1964 (United Press International/Wikimedia Commons); Christine Keeler in the 1960s (Author’s collection).

First published 2013

This paperback edition first published 2024

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Andrew Cook, 2013, 2024

The right of Andrew Cook to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 75249 231 5

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Introduction

Timeline

1 January – Ice Box Britain

2 February – Please Please Me

3 March – End of the Line

4 April – Ban the Bomb

5 May – It’s all in the Game

6 June – Scandal

7 July – The Unthinkable

8 August – I Have a Dream

9 September – Thunderball

10 October – It’s My Party

11 November – Conspiracy of One

12 December – Capitol Asset

Appendices

Source Notes

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the following for their much appreciated assistance in the writing and production of this book: Bill Adams, Jordan Auslander (USA), Dmitry Belanovsky (Russia), Alia Cook, Edward Laxton, Gavin McGuffie, Hannah Renier, Lindsey Smith, Phil Tomaselli, Chris Williamson and the staff at the British Library Newspaper Collections.

Introduction

The year 1963 was a seminal year when most of the things we now associate with the ‘Swinging ’60s’ really began, and this was the theme explored by the BBC TV programme ‘Meet the Author’ when they featured this book shortly after the first edition was published in February 2013. Now, a decade later, the second edition of this book is available for the first time in paperback.

Most years are fortunate if they are dominated by four major ground-breaking news stories during the course of twelve months – 1963, uniquely witnessed on average, four a month. Few years in history are remembered with such fascination as 1963 continues to be. It was the year Beatlemania began, and President John F. Kennedy visited West Berlin and delivered his famous ‘Ich bin ein Berliner’ speech. The final months of the year were, of course, marked by the one of the most tragic events of the decade in the assassination of President Kennedy in Dallas, Texas.

Many of the events and news stories from 1963 were not only of great significance then, but in so many ways continue to influence our lives six decades later. The controversy about membership of the EU began that year and has rumbled on ever since, as does the debate about the facts behind the Kennedy assassination. Who would have thought back in 1963 that the Beatles’ influence and popularity would have actually grown over the decades and that in 2023 they would have their nineteenth number one, ‘Now and Then’. Doctor Who and the Great Train Robbery equally continue to resonate today.

The year 1963 was also the time of my earliest childhood recollection: during the coldest winter for nearly 300 years, my father took me to a lake not far from where we lived; it was completely frozen and we were able to walk across it; we stopped in the middle and my father told me I should never forget that moment as it was unlikely to ever happen again in my lifetime. I never have.

This year was also the year that satire entered the mainstream through a new ground-breaking TV series called That Was The Week That Was, and from where the idea for the title of this book came. The series lampooned the political and social Establishment of the day, targeting figures such as Prime Minister Harold Macmillan and Home Secretary Henry Brooke, who by 1963 seemed to personify a by-gone era. Other targets were the monarchy, the queen, Britain’s declining status as a world power, racism, social hypocrisy and the British class system. Though broadcast well after my bedtime, it seemed that, along with The Beatles, it was to be an on-going topic of conversation between my teenage cousins, although I had no idea who or what they were talking about until many years later.

The concept of 1963 being the gateway to the 1960s and beyond was a theme I lectured on during my time at Birkbeck College, University of London during the mid-1980s. For American undergraduates, keen to understand the British political system and the colossal changes that have taken place since the 1950s, these events provided a ready-made introduction. Much of what follows in this book is taken from the research and lecture notes I wrote at the time. However, thirty years later, we now know a great deal more about 1963 than we did in 1983. I have, therefore, sought to update these chronicles by incorporating new information that has been released by a variety of institutions and archives, both in the UK and the US, during the interim period. This additional material is outlined in the bibliography and sources section at the end of the book.

Most years before and after 1963 have been fortunate to experience more than three or four seminal events during their allotted twelve months; a cursory look through a chronology of 1963, however, reminds us just how many significant events took place that year.

Timeline

JANUARY

• 14 January – George C. Wallace becomes governor of Alabama. In his inaugural speech, he defiantly proclaimed, ‘segregation now, segregation tomorrow, and segregation forever!’

• 14 January – The locomotive the Flying Scotsman makes its last scheduled run

• 18 January – Labour Leader Hugh Gaitskell dies

• 29 January – French President Charles de Gaulle vetoes the UK’s entry into the European Economic Community (EEC)

FEBRUARY

• 11 February – The Beatles record their debut album ‘Please Please Me’ in a single session

• 14 February – Harold Wilson is elected Leader of the Labour Party

MARCH

• 4 March – In Paris, six people are sentenced to death for conspiring to assassinate President Charles de Gaulle. De Gaulle pardons five of them, but the leader of the plot is executed by firing squad a few days later

• 21 March – The Alcatraz Island Federal Penitentiary in San Francisco Bay closes. The last twenty-seven prisoners are transferred elsewhere on the orders of Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy

• 27 March – Dr Beeching issues a report calling for huge cuts to the UK’s rail network

APRIL

• 6 April – Polaris Sales Agreement signed with the USA

• 9 April – Sir Winston Churchill becomes honorary citizen of the USA

• 12 April – Martin Luther King, Ralph Abernathy, Fred Shuttlesworth and others are arrested in a Birmingham, Alabama protest for ‘parading without a permit’

• 15 April – 70,000 marchers arrive in London from Aldermarston to demonstrate against nuclear weapons

• 16 April – Martin Luther King issues his Letter from Birmingham Jail

MAY

• 2 May – Thousands of African-Americans, many of them children, are arrested while protesting against segregation in Birmingham, Alabama. Public Safety Commissioner Eugene ‘Bull’ Connor later unleashes fire hoses and police dogs on the demonstrators

• 8 May – Dr No, the first James Bond film, is released in the USA

• 9 May – The Army of the Republic of Vietnam opens fire on Buddhists who defy a ban on the flying of the Buddhist flag

• 11 May – Everton win the Football League Championship

• 15 May – Tottenham Hotspur win the European Cup Winners’ Cup by beating Athletico Madrid 5-1 in the final

• 25 May – Manchester United win the FA Cup by beating Leicester City 3-1 at Wembley

JUNE

• 5 June – War Minister John Profumo resigns from the government and Parliament

• 11 June – In Saigon, a Buddhist monk commits self-immolation in protest against the oppression of Buddhists by the government of Ngo Dinh Diem

• 11 June – Governor George C. Wallace stands in the door of the University of Alabama to protest against integration, before stepping aside and allowing African-Americans James Hood and Vivian Malone to enroll

• 11 June – President John F. Kennedy delivers an historic Civil Rights address, in which he promises a Civil Rights Bill

• 16 June – Soviet cosmonaut Valentina Tereshkova is the first woman in space on board Vostok 6

• 21 June – Pope Paul VI succeeds Pope John XXIII as the 262nd pope

• 26 June – John F. Kennedy gives his ‘Ich bin ein Berliner’ speech in West Berlin

JULY

• 7 July – Kim Philby is named as the ‘Third Man’ in the Burgess and Maclean spy ring. His defection to the Soviet Union is confirmed

• 12 July – Pauline Reade, 16, is abducted and murdered by Myra Hindley and Ian Brady in Manchester

• 30 July – The Soviet government announce that Kim Philby has been granted political asylum

AUGUST

• 5 August – The USA, UK and Soviet Union sign a Nuclear Test Ban Treaty

• 8 August – The Great Train Robbery takes place at Cheddington, Buckinghamshire

• 18 August – American Civil Rights Movement: James Meredith becomes the first black person to graduate from the University of Mississippi

• 21 August – Cable 243: in the wake of the Xa Loi Pagoda raids, the Kennedy Administration orders the US Embassy in Saigon to explore alternative leadership in South Vietnam, opening the way for a coup against Diem

• 28 August – Martin Luther King delivers his ‘I have a dream’ speech on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial

SEPTEMBER

• 5 September – Model Christine Keeler is arrested for perjury. On 6 December she is sentenced to nine months in prison

• 15 September – American Civil Rights Movement: The 16th Street Baptist Church bombing in Birmingham, Alabama kills four and injures twenty-two

• 17 September – RAF Fylingdales, the ballistic missile early warning radar station on the North Yorkshire Moors, becomes operational

• 23 September –The Robbins Report on Higher Education is published; it recommends that university places should be available to all those who are qualified for them by ability and attainment

• 24 September – The US Senate ratifies the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty

• 25 September – The Denning Report on the Profumo Affair is published by Her Majesty’s Stationery Office (HMSO)

OCTOBER

• 10 October – Prime Minister Harold Macmillan announces that he will resign as soon as a successor has been chosen

• 10 October – The second James Bond film, From Russia with Love, opens in London

• 19 October – Sir Alec Douglas Home succeeds Harold Macmillan as prime minister

NOVEMBER

• 2 November – South Vietnamese coup: South Vietnamese President Ngo Dinh Diem is assassinated following a military coup

• 6 November – Vietnam War: coup leader General Duong Van Minh takes over as leader of South Vietnam

• 22 November – The Beatles’ second album, With The Beatles, is released

• 22 November – President John F. Kennedy is assassinated in Dallas, Texas. Governor John B. Connally is seriously wounded, and Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson becomes the thirty-sixth president

• 23 November – John Kilbride, 12, is abducted and murdered by Myra Hindley and Ian Brady in Manchester

• 23 November – The first episode of the BBC television series Doctor Who is broadcast

• 24 November – President Kennedy’s alleged assassin, Lee Harvey Oswald, is shot dead by Jack Ruby in Dallas, Texas on live national television

• 24 November – President Lyndon B. Johnson confirms that the USA intends to continue supporting South Vietnam militarily and economically

• 25 November – John F. Kennedy is buried at Arlington National Cemetery

• 29 November – President Lyndon B. Johnson establishes the Warren Commission to investigate the assassination of President Kennedy

DECEMBER

• 3 December – The Warren Commission begins its investigation

• 21 December – Cyprus Emergency: inter-communal fighting erupts between Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots

January – Ice Box Britain

Newspaper headlines have a habit of describing bad weather as the worst in the century, or since records began in 1659. But the winter of 1962/63 really was unforgettably cold. Within living memory, only the winter of 1947 has rivalled it for sheer misery. In 1963, just eighteen years after the war, most people still did not have central heating or cars, and shortages of fuel and power made life grim. The number of people dying of the usual winter illnesses rose dramatically in the first three months of the year.

It started unremarkably enough, with light snow on 20 November. The first few days of December saw temperatures fall below freezing, despite the sunshine, which was followed by thick, often freezing, fog. (Implementation of the 1956 Clean Air Act was gradual; in some towns coal still caused major pollution and reduced air quality.)

On the afternoon of Boxing Day, snow drifted down in huge flakes and began to settle. By early evening, frozen points at Crewe were delaying trains from the north, creating a tailback of trains at signals further up the line; the Glasgow–London train was among them. When signals forced it to wait in the dark at a point some way past Winslow, the driver found that the phone didn’t work at the Coppenhall signal-box ahead and chose to ignore a red light. He drove his train slowly past it to the next signal-box. What he could not see, in darkness through swirling snow, was a stationary train ahead; the 16.45 from Liverpool–Birmingham. He collided with the back of it at about 20mph; its rear coaches were telescoped, killing eighteen and injuring thirty-four.

More thick snow fell every day until 29 December, when blizzards began. Local councils up and down the country were kept busy salting the roads; snowdrifts were 3ft deep and in most places travel by car was impossible. People postponed journeys by road, but the weather didn’t improve; trains were delayed all over the country. Pipes were frozen and local authorities had to open stand-pipes in the roads. Householders – usually the women – trudged through the snow to these and filled buckets several times a day. Without a stand-pipe they could not wash, flush lavatories or cook, and disposable nappies for babies were too expensive for most mothers then, even if they had access to them.

Freezing temperatures did not abate. Snow blanketed the whole of Britain until the end of January, and lay thick until March in some areas. Snow was reported to be 6in deep in Manchester city centre, 9in deep in Leeds and about 18in in Birmingham. By the end of January, the sea had frozen for 1 mile out from shore at Herne Bay in Kent. From Windsor upstream, the Thames was frozen from bank to bank. To make matters worse, members of the militant Electrical Trades Union (ETU) began to ‘work to rule’ in power stations. Power cuts closed cinemas and theatres, and prevented floodlit football fixtures, not that many matches could have been played; most were called off because of frozen pitches. Street lighting flickered and traffic lights stopped working. The roads were dangerous already, with people falling over and cars skidding or getting stuck. A country accustomed to using public transport found it too cold to wait for a bus. Trains were constantly delayed by frozen points.

To keep roads open at all, councils had frozen snow shovelled onto lorries and piled up on open land. Salting the roads became ineffective as it required a certain amount of traffic to mix it in and melt the ice and snow; this traffic failed to arrive, especially at night and at weekends when temperatures were very low.

Icy weather soon began to affect the economy; food prices rose. The average wage was £16 per week, a working person’s often closer to £12. Tomatoes and Cox’s apples went up to sixpence a pound; eggs were a shocking four and six (about 24p) a dozen; and potatoes sevenpence per pound.

Between 21 and 25 January, freezing fog returned, which made driving particularly dangerous. Diesel fuel froze, studding the highways with broken down vehicles. The cold spell was in its fifth week when the ETU’s work to rule ended, but it took some time for normal service to resume and power cuts persisted in the meantime.

When a thaw did set in, water mains burst; according to some reports, 200,000 gallons of water a day were pouring to waste in towns and cities as a result of leaks and broken mains. And with the end of January, the cold weather returned. Throughout the first week of February there was heavy snow and storms, with gale-force winds reaching Force 8 on the Beaufort scale. A thirty-six-hour blizzard caused heavy drifts that were 20ft deep in some areas. Midwives, district nurses, emergency doctors and NHS staff – like everyone else – struggled to work through it all.

Where cars could still drive, they were being affected by road salt, rust and corrosion. The press reported that old paraffin heaters were being brought out and used, causing fires. People knocked them over or tried to refill them without turning them off first, causing a horrible whoosh of flame and setting themselves and their home alight; fire brigades were kept busy.

The 1 March, said the papers excitedly, was ‘the warmest day since November’, but temperatures descended below freezing again at night. However, the spring thaw really had begun now, and on 5 March no frost was recorded in the morning and the last traces of the Boxing Day snow had vanished. On 8 March it rained; on 13 March, crocuses bloomed; and on 6 April, there were daffodils. The daffodils appeared six weeks later than usual.

Sports fixtures resumed. Football was way behind schedule, with some FA Cup matches having been postponed as many as ten times, and some league sides had every fixture cancelled between 8 December and 16 February. When spring came, they played three times a week to catch up. Rugby (Union and League) was much the same. As for horse racing, which had seen not a single race between 23 December and 7 March, it was a very bad year for bookies.

Britain breathed a sigh of relief, for it had been a dreadful winter.

Death of Hugh Gaitskell

The Leader of the Labour Party, Hugh Gaitskell, died on the evening of 18 January 1963 at the age of 56 after a short illness. As Leader of the Opposition for the past seven years, he was, by common consent, almost on the threshold of 10 Downing Street. By the end of 1962, not only his own party, but a good many Conservatives, expected him to be prime minister before the next autumn.

He had had an interesting background: Winchester and Oxford, a certain radicalisation as a result of the General Strike, and a career as an academic economist, which included the momentous years of 1933 and ’34 in Vienna. He spent the war years working with Hugh Dalton at the Ministry of Economic Warfare, which ran the Special Operations Executive (SOE) whose personnel assisted in sabotaging the Axis powers overseas.

Gaitskell was elected Labour MP for Leeds South at the 1945 General Election, which Labour won by a landslide. Promotion came quickly and within two years he was appointed to the Cabinet as Minister of Fuel and Power. When Sir Stafford Cripps fell ill and had to resign as Chancellor of the Exchequer, Gaitskell was chosen to take his place. This was seen at the time as the result of Hugh Dalton’s influence, and Gaitskell turned out to be a controversial chancellor; the National Health Service (NHS), the jewel in Labour’s crown since its inception in 1948, suddenly imposed charges for prescription spectacles and false teeth. (One reason for the charges was that Britain, which was still broke, with food rationing and a huge demand for housing, was required to contribute to the funding of the Korean War.) Aneurin Bevan, Harold Wilson and John Freeman resigned over the prescription charges, which they felt violated the fundamental principle of the NHS, and from then on there was recurrent conflict between Left and Right in the party.

Labour was defeated in 1951, and again in 1955, and after that second defeat Clement Attlee resigned as Party Leader; Gaitskell beat Aneurin Bevan and Herbert Morrison to the post.

Gaitskell was forceful in opposition; in particular during the Suez Crisis in 1956. President Nasser of Egypt had suddenly nationalised the Suez Canal, a route of enormous importance to world trade. Israel invaded, and Britain and France issued an ultimatum to both countries; when Nasser failed to respond, they bombed Cairo. This was a terrible move, carried out without the support of the United Nations (UN). The Russians, who supported Nasser, were furious; the Americans were appalled; and the British and French were forced to retire with ignominy. It turned out that Britain and France had orchestrated the entire episode with the Israelis in the first place. Gaitskell was scathing in Parliament, and he had public support.

Nevertheless, Labour failed yet again to win in 1959. Notwithstanding the Festival of Britain, people still associated the Labour Party with the grey years of post-war impoverishment and the Conservatives exploited that with their slogan: ‘Life’s better with the Conservatives! Don’t let Labour ruin it.’

Gaitskell did not prevaricate: he knew what he wanted. On every issue, you knew where you were with him and it was unlikely to be on the Left. The major exception to this rule was his stance on the Common Market. Macmillan was trying to get Britain in, but Gaitskell, like the Left of the Labour Party, opposed him because he said the country would lose its independence: it would be ‘the end of a thousand years of British history’.

Bevan, Wilson and others on the Left proclaimed rigid commitment to nationalisation, as under Clause 4 of the Party’s constitution:

… to secure for the workers by hand or by brain the full fruits of their industry and the most equitable distribution thereof that may be possible upon the basis of the common ownership of the means of production, distribution and exchange, and the best obtainable system of popular administration and control of each industry or service.

Gaitskell was flexible on nationalisation, and he also refused to commit Labour to the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament’s aim of unilateral disarmament.

He was due to visit the Soviet Union in the New Year of 1963. He had had the flu in December, but was pronounced fit to travel; after all he had recovered and was younger than Attlee, Eden or Macmillan had been when they took office.

However, immediately after Christmas, he fell ill again, and the trip to meet Nikita Khrushchev had to be cancelled. On 4 January he was admitted to the Middlesex Hospital with what turned out, two days later, to be serious kidney trouble. On 17 January, an unsuccessful kidney transplant was performed; there were repeated attempts at dialysis, but his heart and lungs seemed too weak to stand the strain. At 9.10 p.m. on 18 January, his organs suffered a total failure and he died; his wife Dora was by his side.

Messages flooded in from the queen, Kennedy, Khrushchev, Lord Attlee and national leaders all over the world, many of whom had expected that, after the 1964 British election, Gaitskell would be prime minister. Then the conspiracy theory began.

Dr Somerville, from the Middlesex Hospital, thought there was something fishy going on. Three days later he contacted MI5; its Director General, Roger Hollis, was immediately interested. Anatoli Golytsin, a recent defector from Russia, had revealed that the KGB was planning a political assassination in Europe in order to replace the victim with a man of their choice. Hollis suggested that Arthur Martin, Head of the Russian Counter-espionage section, should find out what Dr Somerville had to say.

Dr Somerville told him that Gaitskell had died of lupus disseminata. This, he apparently said, was an extremely rare disease, almost unknown in temperate climates, and in the past year Gaitskell had not been anywhere where he could have caught it.

Martin consulted the Government’s Chemical and Microbiological Laboratory at Porton Down in Sussex, where Dr Bill Ladell, who was very knowledgeable about chemical and biological warfare, said that nobody knew how lupus disseminata was transmitted. It might be a fungus, but that didn’t help in knowing how it was contracted. Martin then asked the CIA to find out from Russian scientific papers whether the Soviet agencies might have considered using lupus surreptitiously to bring about death. They sent MI5 an English translation of a 1958 Russian scientific journal which described the use of a chemical that the Russians had discovered that could induce lupus in experimental rats; however, the quantities required to produce lupus were considerable and had to be given repeatedly. Dr Ladell, having read a copy of the CIA’s response, suggested that if the Russians had continued their lupus research in the five years since they produced the paper, they may well have found a more effective form of the chemical, requiring much smaller doses.

The story seems unlikely. Gaitskell was surely less of a threat to socialism than the Tories; why choose to assassinate him unless they were sure they had their own man ready to take his place? But Harold Wilson, his successor, followed the usual path of radicals in office, demonstrating by compromise that politics is the art of the possible.

However he died, Gaitskell’s reputation also remains subject to debate. Would 1960s Britain have fared any better under the leadership of such a man, fabled for his principles, as opposed to Wilson? Harold Wilson, by the early 1970s, was viewed by many as an unprincipled chameleon. A conviction politician some twenty years before conviction politics became the vogue, Gaitskell could well be seen as a politician ahead of his time. Had he lived, he might have won a larger majority in 1964 than Harold Wilson. Even with a smaller win, it seems likely that he would have pushed ahead with a tougher, more radical agenda than the more cautious Wilson. On economic policy, for example, he would doubtless have gone ahead and devalued the pound within months of the election (unlike Wilson, who did not grasp the nettle until late 1967). Gaitskell would also have pushed through legislation to curb unofficial ‘wild-cat’ strikes, if necessary risking a head-on conflict with the Trade Union Movement. Being a virulent anti-marketeer, he could well have vetoed any further moves by Britain to seek membership. In his day, though, the gift of Common Market membership was still very much in the hands of the French, who four days before his death made their views on the matter profoundly clear.

‘Non’

When France, West Germany, Italy, Belgium, Luxembourg and Holland formed the Common Market in 1958, Britain feared membership would have too severe an impact on its Commonwealth markets, which still counted for a large part of the nation’s trade.

Instead, the Macmillan government opted to create a rival, looser free trade area with the Scandinavian countries, plus Portugal and Switzerland, which was collectively known as the European Free Trade Area or EFTA. Within five years, however, the economic remedies employed by Macmillan and his chancellor, Selwyn Lloyd, failed to have any real impact on Britain’s growing inability to match the economic growth and rise in living standards being achieved by the six Common Market countries. Fearing he may have missed the European boat, Macmillan began a round of diplomacy, which culminated in an announcement in 1961 that Britain desired to seek membership to the Common Market.

Having previously been invited to join, and having (so far as the rest of Europe was concerned) arrogantly rejected the offer, Macmillan was now having to apply from a position of weakness. In particular, he encountered scepticism from France and, to a lesser extent, from West Germany. Both saw Britain as half-hearted in its commitment to the ideals of European unity and feared Britain’s continuing close ties with the United States.

This European wariness became apparent in December 1962, when Macmillan held talks with French president Charles de Gaulle. Macmillan discovered that, far from mellowing, de Gaulle had become more intransigent. Britain, he thundered, had not yet thrown off its old bonds with the United States, and Macmillan had failed to convince him that he was prepared to be a good European rather than an apologist for the Americans. Why, then, Macmillan muttered as he listened to this, had the French allowed the talks to drag on for so many weary months if they were opposed to the British application all along?

On 14 January 1963, at an Elysée Palace press conference, de Gaulle humiliated Macmillan by announcing his reservations to a worldwide audience: ‘England is insular,’ he boomed to the assembled media, ‘bound up by her trade, her markets, her food supplied by the most varied and often the most distant countries ... In short, the nature and structure and economic context of England differ profoundly from those of the other states of the Continent.’ Should Britain be allowed to join the Common Market, he continued, ‘in the end there would appear a colossal Atlantic community under American dependence and leadership which would soon swallow up the European Community.’ He had, he concluded, decided to veto Britain’s application.

Macmillan sought to redress matters by making a live television broadcast on BBC and ITV the following day. With the very picture of patrician composure, he admitted that ‘a great opportunity has been missed’, but was quick to blame the ‘misguided’ de Gaulle for the failure.

The perceived half-heartedness of Macmillan’s application had undoubtedly made it easier for de Gaulle to oppose it. Macmillan’s chance of success might have been better had he applied for membership immediately after the 1959 election, when his popularity and prestige were at their height, and when the French president’s personal position at home was still weak and uncertain. Having missed that opportunity, Macmillan had compounded his European difficulties by pressing ahead with nuclear weapons co-operation talks with President Kennedy in December 1962. These could easily have been postponed until after his talks at the beginning of January with de Gaulle.

That aside, the responsibility for the foundering of the application ultimately lay with de Gaulle, not with Macmillan. The news of the veto was, if anything, greeted with relief by a large section of the British public, along with the majority of the popular press. ‘Glory, glory, Hallelujah!’ proclaimed the Daily Express. ‘It’s all over; Britain’s Europe bid is dead. This is not a day of misery at all. It is a day of rejoicing, a day when Britain has failed to cut its own throat.’

Macmillan’s chief negotiator, Edward Heath, continued to believe that Common Market membership would be the economic panacea to Britain’s troubles. He would eventually secure entry for Britain in 1972, albeit on less favourable terms than those sought in 1961–62. Ironically, the United States, whose silent shadow had hung over Britain’s application from the start, was about to change course on the other side of the world. President Kennedy, who had encouraged Macmillan to seek membership partly because he saw the Common Market as a positive move away from European colonialism, was about to embark on a crippling colonial war many thousands of miles away in a former French colony in South East Asia.

Vietnam: the Battle of Ap Bac

‘We’ve got them in a trap,’ growled US General Paul D. Harkins, ‘and we’re going to spring it in half an hour.’ He was talking about a unit of Communist Viet Cong fighters in the South Vietnamese hamlet of Ap Bac. New York Times correspondent David Halberstam made a note; he had asked Harkins to comment on rumours of a skirmish, and had inadvertently stumbled on a story that would typify the forthcoming decade of news coverage in Vietnam.

The situation in Vietnam had been deteriorating for years, after the country had been split into North and South in 1954. Under the Geneva Accords of that year, the general idea was that Communist sympathisers would move north, and the rest would go south, and in the end there would be one Vietnam with a democratically elected government, living more or less in harmony. Ho Chi Minh, now an old man and no longer Party Leader, but still a figure of influence, was still banking on an election that would unite the two sides. The South Vietnamese Government was in no hurry to hold one since they feared the Communists would win.

Meanwhile, in the paddy fields and forests of the south, militant Communists who should have moved north still remained. They had formed the Viet Cong to fight a guerrilla war against the hated South Vietnamese regime, headed by President Ngo Dinh Diem. Towards the end of 1962, Diem had launched an anti-Communist offensive aimed at driving out a small band of Viet Cong fighters embedded in the jungles of South Vietnam. The Viet Cong were on their own, as the North Vietnamese rejected taking any military action which might incite the United States to intervene in support of Diem.

President Diem’s new campaign was showing early signs of success, and the Viet Cong, however disadvantaged, had to do something. At first they simply retreated to increasingly remote hamlets in the hills and river estuaries of South Vietnam. Poorly trained, ill-motivated and ill-equipped South Vietnamese forces took several days to get anywhere near them, and simply allowed themselves to be led deep into territory in which they could easily be encircled. Strategically, chasing the Viet Cong was pointless.

American ‘advisors’ had begun arriving in South Vietnam early on in the Kennedy Administration. In fact, they were Special Forces who took an active involvement in the conflict from its inception, aided and abetted by effective CIA intelligence. But at last the Pentagon began to supply helicopters, which changed the nature of the conflict considerably by allowing South Vietnamese forces to fly to almost any part of the country where they spotted a Viet Cong presence. The helicopters, as well as new armoured personnel carriers (APCs), took a heavy toll on Viet Cong units from late 1962 onwards. The lightly armed Viet Cong had no weapons capable of stopping the APCs and were forced to flee, suffering heavy casualties.

Yet, they did get away, as South Vietnamese officers were often reluctant to risk their lives chasing Viet Cong. This frustrated the CIA, who saw timidity as a lack of commitment.

In the first few days of 1963, the CIA deployed even more advanced technology. American aircraft with eavesdropping equipment searched for Viet Cong radio transmitters and met with almost immediate success. They intercepted Viet Cong radio signals from the hamlet of Ap Tan Thoi; clearly this was a guerrilla command centre. CIA analysts reported that the Viet Cong were planning to deploy about 120 men to defend their radio transmitter, which was a captured American model.

US intelligence had tracked down Viet Cong wth transmitters before, but they had usually melted into the landscape before South Vietnamese soldiers could get to them. The CIA knew where the Viet Cong were, but they didn’t know that they’d changed their policy. They weren’t going to play ‘come and get me’ any more; the next time the South Vietnamese came looking for them, they intended to stand their ground and fight.

On 2 January, the South Vietnamese had about 320 troops, including Civil Guard, in Ap Bac and Ap Tan Thoi. At 4.00 a.m., Viet Cong scouts reported hearing truck engines close to Ap Bac and, as a result, the Viet Cong dug in while the villagers fled to hide in nearby swamps.