Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

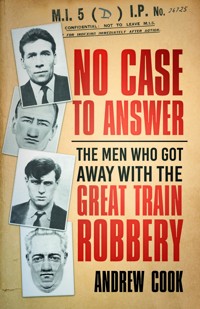

'There I met and was introduced to 13 men, one of whom I already knew. Three of these men and another who joined the group later have never, to my knowledge, been wanted by the police in connection with the train robbery so, for their protection, I will refer to them as, Joe, Bert, Sid, and Fred.' - Ronnie Biggs In the early hours of Thursday, 8 August 1963, sixteen masked men ambushed the Glasgow-Euston mail train at Sears Crossing in Buckinghamshire. Making off with a record haul of £2.6 million, the robbers received approximately £150,000 each (over £2 million in today's money). While twelve of the robbers were jailed over the next five years, four were never brought to justice – they evaded arrest and thirty-year prison sentences, and lived out the rest of their lives in freedom. In stark contrast to the likes of Ronnie Biggs, Buster Edwards and Bruce Reynolds, they became neither household names nor tabloid celebrities. Who were these men? How did they escape detection for so long? And how, almost sixty years later, are their names not common knowledge? In No Case to Answer, Andrew Cook gathers and examines decades of evidence and lays it out end-to-end. It's time for you to draw your own conclusions.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 464

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

To Alia

Jacket illustrations

Front: MI5 report, 13 January 1964 (The National Archives); an Identikitpicture of ‘Old Alf’ (Thames Valley Police); Danny Pembroke CRO photograph(Metropolitan Police); Harry Smith CRO photograph (Metropolitan Police);Police at the scene of the Great Train Robbery (Evening Standard/Getty Images).

Back: MI5 folder (The National Archives); postcard from Cannes, allegedly from Terry Hogan (Police & Gendarmerie Records, High Court of Grasse, France);

Danny Pembroke criminal intelligence file (BPMA); Danny Pembroke in the army (Danny Pembroke Jnr).

Back cover quote from Ronnie Biggs’ serialisation in The Sun, 20–28 April 1970, reproduced from the Metropolitan Police Files.

First published 2022

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Andrew Cook, 2022

The right of Andrew Cook to be identified as the Authorof this work has been asserted in accordance with theCopyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprintedor reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic,mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented,including photocopying and recording, or in any informationstorage or retrieval system, without the permission in writingfrom the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 8039 9070 5

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Preface

PART 1: ONCE UPON A CRIME

1 Scoop of the Century

2 The Mister Men

3 A Little Cloak and Dagger

4 That Riviera Touch

5 An Inspector Calls

6 The Big Job

PART 2: FISH OFF THE HOOK

7 Night Owls

8 Doing a Deal

9 Safe as Houses

10 X Marks the Spot

11 A Sound Investment

12 There for the Taking

13 The Insider

14 The Outsider

PART 3: WILL THE REAL BILL JENNINGS PLEASE STAND UP

15 The Bookworms

16 Three-Card Monte

17 Tinker, Tailor

APPENDICES

Appendix 1: Metropolitan Police Structure 1963

Appendix 2: Telephone Tapping

Appendix 3: Metropolitan Police Districts and Divisions

Appendix 4: The Post Office Solicitor

Appendix 5: The Cahill Companies

Notes

Bibliography

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

IT IS UNFORTUNATELY NOT possible in a book of this kind to acknowledge, properly and by name, certain individuals who have provided extensive help, documentation and assistance in the researching of key aspects of this story. Those individuals do, however, know who they are, and have been privately thanked for the information and cooperation they provided, and indeed for the fascinating hours of their time they spent with me.

Audrey and Diana in South Africa, Bill Adams, Jill Adams, Sue Adcock (Hampshire Police), Anne Archer (BT Archive), Jordan Auslander (USA), Colin Boyes (Thames Valley Police), Garry Forsyth (Chief Constable Bedfordshire Constabulary), Philippe Chapelin (France), Daksha Chauhan, Alia Cook, Neeta Davda, Jim Davies (British Airways Heritage Collection/Archive), Garry Forsyth (Chief Constable Bedfordshire Constabulary), Gina Hynard (Hampshire Archives & Local Studies Centre), Mary Jursazek, Colin Kendall, Dick Kirby, Suhalia Liaquat, Michelle McConnell, Gavin McGuffie (Royal Mail Archive), Andrew Minney, Jade Pawaar, Danny Pembroke Jnr, Amanda Rossiter, Dr Tim Ryan, Yagnesh Shah, Lindsay Siviter, Sue Smith (Metropolitan Police), Lionel Stewart (Bedfordshire Police), Phil Tomaselli, Steve Walsh, Kevin Welch, Ken Wells (Thames Valley Police), Richard West, Alisa Wickens (Wiltshire Police)

PREFACE

THIS BOOK IS BASED on several years of carefully documented research, studying over a thousand pages of new material. Much of the detail recorded here has never before seen the light of day, being from closed, redacted, unfiled or retained sources.

My earlier book, published in 2013, The Great Train Robbery: The Untold Story from the Closed Investigation Files, was essentially the story of the robbery itself. It was based, on the whole, on over 1,000 pages of documents from investigation files that had been opened as a result of Freedom of Information (FOI) requests. The book was later used as a source for two television documentaries on the robbery, and the 2013 two-part World Productions/BBC1 television movie The Great Train Robbery: A Robber’s Tale & A Copper’s Tale. It was a great privilege to work with scriptwriter Chris Chibnall, and to watch the stars of the film, Jim Broadbent, Luke Evans, Robert Glenister, James Fox, Paul Anderson, Martin Compston, and a whole host of other great actors, bring the story to life during filming.

This second book, however, is about something very different. It is not really about the robbery itself, although inevitably its thread runs throughout the book. Almost anyone who has ever heard of the Great Train Robbery knows the names of those who will forever be associated with it – Bruce Reynolds, Buster Edwards, Gordon Goody, Ronnie Biggs, and so forth. They are virtually household names today. However, from the moment I first read Colin McKenzie’s book The Most Wanted Man over forty years ago, I was intrigued more by the untold story of the robbers who had no need to go on the run, were not handed down thirty-year sentences, and did not live their lives out of suitcases, forever looking over their shoulders. This book is about how and why they remained at liberty, and why the Director of Public Prosecutions deemed in 1964 that they had ‘no case to answer’ as far as the British judicial system was concerned.

Neither this book, nor the previous one, could ever have been written without the advent of Freedom of Information legislation in this country, and other countries around the world, during the past two decades. That in itself has not been a panacea, for a whole host of new obstacles and barriers have sprung up to counter it during the same period of time.

The ball really started rolling when the Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, William Waldegrave, announced on 25 June 1992 the first tentative steps on the long and rocky road that would eventually lead to the UK’s Freedom of Information Act: ‘I would like to invite serious historians to write to me … those who want to write serious historical works will know, probably better than we do, of blocks of papers that could be of help to them which we could consider releasing.’

The response from historians, serious and otherwise, came a close second to rivalling the sacks of mail addressed to Santa Claus received every Christmas in sorting offices up and down the country. Thankfully, unlike Santa’s mountain of mail, the Post Office had a Whitehall address to which Waldegrave’s missives could be delivered.

Very few of those who put pen to paper were to receive much more than a cursory letter of acknowledgement. Still fewer were to get the green light to embark on the process of submitting references, a curriculum vitae and a list of previous publications. I was one of the fortunate few. My initial request was in respect to the MI6 spy Sidney Reilly and his activities in Russia shortly after the 1917 Revolution. Having successfully navigated my way through the vetting process, I eventually received a letter setting out the conditions for granting me access to the files I had requested. Suffice to say that none of these were found by myself to be in the least bit unreasonable or objectionable, and I was more than happy to sign a declaration acknowledging my obligations under the Official Secrets Acts, an undertaking I have abided by to this day.

I was fortunate, over the following two decades, to have been granted further access to other closed files on a range of topics. During that time, the Freedom of Information Act was passed in 2000 and came into effect on 1 January 2005. The Act gave citizens the right to access information held by public authorities. The intention of the Act was to try to make government more transparent and to increase public confidence in political institutions. Some have argued, over the past fifteen years or so, that this has either failed to achieve its objective or, in some cases, has actually achieved the opposite.

The percentage of Freedom of Information requests granted in full has apparently fallen from 62 per cent in 2010 to 44 per cent in 2019. Requests flatly denied have grown from 21 per cent to 35 per cent in the same period. The Ministry of Justice, the Treasury, the Health Department and the Home Office all have high rates of rejecting FOIs. The department with the highest number of FOI rejections is the Cabinet Office, which declined 60 per cent of FOI requests in 2019. The Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO), the regulator for the Freedom of Information Act, has seen its funding fall by 41 per cent in real terms in a decade, while the number of FOI complaints have grown significantly.

According to Katherine Gunderson of the Campaign for Freedom of Information, ‘Authorities have learnt that they can breach FOI deadlines and even ignore the ICO’s interventions without repercussions.’ Jon Baines, an FOI expert at the law firm Mishcon de Reya, has highlighted a tactic known as ‘stonewalling’, which involves public bodies, who are required to respond to Freedom of Information Requests within twenty working days, simply ignoring the request. Without a formal refusal, requesters cannot appeal to the Information Commissioner.

While I have certainly experienced a number of tactics over recent years to avoid responding to FOI requests or to release information, it has to be said that in some instances, funding cuts in the public sector have led to diminishing staff numbers handling such requests. This, in the view of some, has led directly to more FOI requests being rejected out of hand on tenuous grounds. Because of lack of search time, some are resorting to this tactic purely out of practicality, rather than seeking to deliberately withhold information from the public. The fact that files are now closed for a minimum period of twenty years, under the 2010 Constitutional Reform and Governance Act, and not thirty as before, has also dramatically upped the workload of those whose job it is to prepare files for release and consider FOI requests.

It could also be argued, however, that Freedom of Information access, or lack of access, has become a distraction in terms of locating critical source material from the past.

The National Archives has a major clue within its name. The National Archives are, generally speaking, a repository for national records, not local or regional ones. While the Metropolitan Police, for example, is theoretically a police force covering the Greater London area, it is, to all intents and purposes, an unofficial national force. Its detectives, in particular, have more often than not been called in to assist on cases the length and breadth of the country for over 150 years. The Great Train Robbery, a crime that occurred in rural Buckinghamshire, is but one case in point.

Being a national archive, the records of provincial forces involved in the Great Train Robbery investigation, such as Surrey, Hertfordshire, Bedfordshire, Buckinghamshire, City of London and Sussex constabularies, for example, are not to be found at The National Archives. Instead, these ‘provincial forces’ are responsible for their own record keeping, archiving, storage and policy, as is Royal Mail, who hold the records of the world’s oldest criminal investigation department, the Post Office Investigation Branch.

When I first began researching intelligence records well over twenty years ago, I quickly realised that, as with all hierarchical bureaucratic organisations, intelligence departments such as MI5 and MI6 will periodically copy in other government departments, such as the Ministry of Defence, Home Office, Foreign Office, Board of Trade, etc., with documents, particularly if they have a shared interest or are undertaking an assignment from one of them. When, decades later, the departmental weeders are going through files prior to releasing them to The National Archives, they will occasionally miss the significance of a document emanating from an intelligence department, and sign off the entire file as ‘open’ for the purposes of public access. In this way, a copy document, the original of which will never see the light of day, will enter the public domain.

When researching the Royal Mail’s train robbery investigation files, I soon spotted a similar pattern, i.e. the Flying Squad would periodically supply the IB with investigation reports, and vice versa. The same picture emerged when I examined the records of some of the provincial police forces, particularly those in close proximity to London and/or the scene of the crime. They were receiving almost daily reports and telexes from Scotland Yard. Unlike the Metropolitan Police originals, which are mostly closed and inaccessible to the public, these provincial force copies are, on the whole, accessible to the discerning researcher.

Another researching ‘loophole’ that can sometimes be found is in the fact that while a file on a particular individual or event might be closed to the public in the UK, in another connected country where that individual may have visited or operated, open files might exist. Even if such a file is closed in that country, the process for applying for its release may well be less demanding and onerous than in the UK. This has certainly been my experience in a good many cases.

As with organisational records generally, some police files, or individual documents within them, are occasionally thought to be lost. Among the possible reasons that they are not initially locatable might be that material within a case file has been lost while on loan to other departments, other constabularies or other government departments. Equally, documents and files that were returned might not have been put back in the right file or location. Other records may have been accidently attached to, or subsumed by, another investigation file that involved the same detective or offender. Records might also have been separated when a department was split, reorganised, amalgamated or ceased to exist. In a very small minority of cases, some records might not have been catalogued in the first place and therefore do not show up on indexes or databases. The same story is routinely repeated in other law enforcement organisations abroad, including Interpol. An awareness of these possible pitfalls can, after much foraging, result in the unearthing of material previously thought to be off the radar.

There are, of course, other contemporary or near contemporary sources that can, with the aid of the births, deaths and marriage records at the General Register Office, be accessed. While published memoirs are of great value and interest to the researcher, of more interest still are those either never published, never finished or, indeed, never started. The never started variety often comprise copious handwritten background notes that require the patience of a saint to decipher. Those that were never finished are usually legible, and often typed, in hope and anticipation of being published. The unpublished variety are typically those that have either been rejected by a publishing house or written as a personal record for the writer themselves, or as a memento for their children. Of the three, the unfinished memoir, started in a fit of enthusiasm, but stopped dead in its tracks by ill health, boredom or the inability to stick at it, is without doubt the majority experience.

While the popular assumption is that journalists and FOI researchers are primarily focused on contemporary issues, this rather overlooks the fact that past events often impact on the present and the future. Again, the Great Train Robbery is a case in point.

It was, after all, the emergence of the tabloid ‘scoop’ culture in the late 1960s, led by Rupert Murdoch’s newspaper stable, that finally blew the lid off the Great Train Robbery cover-up. Despite the line taken by two successive governments, and Scotland Yard’s top brass, who had told the British public that all those involved in the robbery had been arrested and convicted and, with the exception of the escaped Ronnie Biggs, were now safely under lock and key – the truth was, in fact, quite the opposite.

1

SCOOP OF THE CENTURY

APRIL 1970

THE ENORMOUS CONCRETE AND glass slab in Holborn Circus was Cecil King’s idea of a futuristic headquarters to match his ambition to be Britain’s number one media mogul. With the Daily Mirror, then Britain’s biggest-selling daily newspaper, enjoying bumper profits, King had money to spend, and went on an acquisition spree. By buying up a collection of over 200 newspapers and magazines, he created, in 1963, the International Publishing Corporation (IPC), which instantly became the largest publishing conglomerate in the country.

While the Daily Mirror was the jewel in IPC’s crown, its Daily Herald newspaper was, by contrast, on its last legs. However, the vainglorious King was convinced that he had the Midas touch, and appointed market researchers to devise a strategy to give the paper a phoenix-like rebirth.

The report to the IPC board was, if nothing else, a bold one. He proposed to replace the Daily Herald, whose nose-diving circulation among working-class readers was seen as terminal, with a new bold, modernist broadsheet paper called The Sun. The new paper would, he argued, appeal to middle-class social radicals, who would unite with the Herald’s working-class political radicals to create a new mass readership for the paper. King’s board endorsed the plan, and the first edition of The Sun rolled off the presses to a fanfare of optimism on 15 September 1964.

However, like so many other examples of sixties utopian optimism, the Sun project soon became embroiled in the mires of reality. By 1969, The Sun was losing around £2 million a year and had a circulation of only 800,000, which was lower than the Herald’s readership when it closed five years earlier. By this time, too, the IPC board had fired King himself and resolved to sell The Sun to stem growing losses.

Publisher and Labour MP Robert Maxwell was quick off the mark in putting in an offer and promised to retain The Sun’s commitment to the Labour Party. However, under close questioning from the print unions, he was forced to concede that there would need to be wide-scale redundancies at The Sun in order to turn around its fortunes.1

It was at this point that the Australian media magnate Rupert Murdoch saw his chance. He had recently bought the News of the World Sunday newspaper and was ambitious to own a UK daily paper.

Murdoch craftily bypassed the IPC board and approached the print unions directly, emphasising not only his Australian papers’ support for the ALP (Australian Labor Party), but more significantly, his commitment to make far fewer redundancies than those being touted by Maxwell, if he were to purchase The Sun. To IPC he promised that he would publish a ‘straightforward, honest newspaper’ that would continue to support Labour. IPC, under pressure from the unions, reluctantly rejected Maxwell’s higher offer, and Murdoch bought the paper for a steal at £800,000. This was to be paid over a period of years, which effectively reduced the cost of the purchase still further, as he was then able to use The Sun’s revenue stream to repay IPC.

Murdoch quickly appointed former Mirror sub-editor Larry Lamb as The Sun’s new editor. Lamb was scathing in his opinion of the Daily Mirror, its antiquated work practices and its overstaffed operation. He shared Murdoch’s view that, ‘a paper’s quality is best measured by its sales’.

Lamb immediately set about recruiting 120 new journalists (fewer than half the number employed on the Mirror), who were signed up forthwith and promptly reported for work at 30 Bouverie Street, The Sun’s new premises. One of these new signings was Brian McConnell, Lamb’s choice for The Sun’s news editor, whom he had previously worked with at the Mirror.

Murdoch’s vision of The Sun was to prove a very different one from IPC’s. While The Sun copied the Daily Mirror in several ways – it was, from this point on, tabloid size with the paper’s name in white against a red rectangle. It was also, without doubt, much livelier and punchier, centring itself on human interest stories, exclusive scoops and sex.

The first edition of the Murdoch Sun on 17 November 1969 proclaimed: ‘Today’s Sun is a new newspaper. It has a new shape, new writers, new ideas. But it inherits all that is best from the great traditions of its predecessors.’ While The Sun’s first front page headline was ‘Horse Dope Sensation’, Murdoch knew full well that this was hardly the type of scoop that would be required if The Sun was to topple the Daily Mirror from its perch as the UK’s number one newspaper. The heavy responsibility for finding and exploiting news scoops was to fall on the shoulders of Brian McConnell.

It was often said of McConnell that his greatest claim to fame came from embodying a headline rather than penning one, thanks to a series of events that occured on the evening of 20 March 1974:

McConnell … happened to be in a taxi travelling down the Mall ahead of a royal limousine carrying the princess and her then husband, Captain Mark Phillips, when a car swerved into it and forced it off the road.

Hearing the crash, the cab driver screeched to a halt, and McConnell jumped out to discover the gunman threatening the princess’s bodyguard. Instead of running for cover, McConnell stepped between the royal party and the gunman and tried to reason with him, famously saying: ‘Don’t be silly, old boy, put the gun down.’

The man responded by shooting McConnell in the chest and opening fire on several others, wounding two policemen and the chauffeur before being overpowered … He was later honoured with the Queen’s Gallantry Medal, while the gunman, who had a history of mental illness … ended up in Rampton hospital.2

Throughout his Fleet Street career, McConnell was acknowledged as a Fleet Street character and an instinctive newshound. Known too as ‘a heroic drinker’, he spent many hours entertaining members of the Press Club in Salisbury Court. It was following one such night out in April 1970 that he arrived home rather late. He had not been in long when the phone rang. It was a Scotland Yard officer he had known for some time, responding to a message he had left earlier in the day. Initially making the excuse that he was trying to find out more about a recent bank robbery in the West End, McConnell eventually showed his hand and asked who The Sun should contact at Scotland Yard if, by chance, they ever came across information about an undisclosed high-profile robbery from some years ago? The officer at first sounded a little surprised, but after a few failed attempts to elicit more from McConnell, finally gave in and volunteered the Scotland Yard phone extension number for the private secretary of Assistant Commissioner (Crime) Peter Brodie.3

The following day, McConnell phoned the Yard:

Memo to Mr H Hudson, A/A.C.C. – 14.4.70

At 12.20 p.m. I received a telephone call from a Mr McConnell, News Editor of ‘The Sun’ newspaper. He informed me that his editor Mr Larry Lamb, had in his possession a document regarding a crime of major importance – McConnell himself does not know what the document contains – he wishes to hand a copy of it to Mr Brodie or his Deputy. I informed him that Mr Brodie was on leave and that you were A/A.C.C. and was not at present available. This message would be passed on and that he would hear from us later today. Mr McConnell’s tel. no. 353-3030 extn. 337.4

At 2.40 p.m., Deputy Assistant Commissioner Crime Harold Hudson spoke to McConnell’s secretary, and at 3.40 p.m. it was arranged that he, Deputy Assistant Commissioner Bernard Halliday and Commander Wally Virgo would meet Larry Lamb at 2 p.m. the following day at his Bouverie Street office. However, this was postponed at the last minute by Lamb, as The Sun’s legal representative was not available until later in the afternoon. As a result, the meeting eventually took place at 3.40 p.m., when Lamb and McConnell were flanked by not one, but two lawyers.5

Larry Lamb wasted little time in pleasantries and apparently handed the Yard men two sealed envelopes the moment they sat down, saying that he thought the contents would be helpful to the police in the investigation of the ‘Biggs Case’. He asked that the police read the documents and offer any comment they might think fit. He also pointed out that each page bore a fingerprint and a signature, and wondered if the Yard could oblige by authenticating them. Lamb went on to say that he realised some parts of the manuscript were libellous, but having taken legal advice, The Sun would not publish anything detrimental to the police.

The Sun’s lawyers then emphasised that neither Lamb, McConnell, nor indeed anyone else connected to The Sun, had at any time any personal contact with either Biggs or anyone else who might be considered his agent. Rather than be drawn on the spot, Hudson told Lamb that they would give him a receipt for the two envelopes and take them back to the Yard to study. They would then get back to him as soon as they could.

On arrival back at the Yard, the three officers, along with Deputy Assistant Commissioner Crime (HQ Operations) Richard Chitty, eagerly tore open the envelopes. In the smaller of the two were copies of two letters addressed to J.T. Hassett Esq., c/o Walter & Hassett, Solicitors, 178 Queen Street, Melbourne, and signed ‘R.A. Biggs’ and ‘Ronald A. Biggs’. In the second, much larger envelope they discovered seventy-seven pages of typescript, each of which bore a fingerprint and the signature ‘R.A. Biggs’ and one page that bore two fingerprints and the signature ‘R.A. Biggs’.6

The seventy-seven pages of typescript were apparently Biggs’s life story, from his birth in August 1930 to present, detailing in particular his involvement in the planning and execution of the ‘Great Train Robbery’, the events that immediately followed his arrest, remands in prison, his committal, trial and sentence, and finally his escape from the prison. It was immediately agreed that the documents should be handed over to Commander Peat of C.3 (fingerprints), and Reginald Frydd in the Yard’s Forensic Science Laboratory.

The following day, Peat reported that he had identified the clearest of the fingerprints as being identical with the left forefinger print of Biggs. While this was clear, he also made clear that it was not possible to say that Biggs had actually made the impression himself on each page of the typescript and, in fact, his guess was that these prints were probably made from a cast or stamp. Frydd’s report stated that in his opinion the signatures appearing on the documents had been traced or copied from ten or twelve specimen signatures, and were therefore ‘not the true signature of Biggs’. Frydd further speculated that he felt the signatures had certain female characteristics, and arrangements were now in hand to compare these with samples of Charmian Biggs’s handwriting.7

After reporting the findings to the Commissioner, Sir John Waldron, the advice of the Solicitor to the Metropolitan Police was then sought, and he gave his opinion that The Sun could and should be told of the findings and opinions respecting the fingerprints and the signatures. He also pointed out that not to do so would obviously not prevent publication, and could, in certain circumstances, lead to unfavourable comment about the police in any subsequent publication of the story by The Sun. It was also agreed, in a meeting between Waldron, Chitty, Halliday and Hudson, that over and above this, the police would make no comment at all on the content of the seventy-seven-page document, its validity, or indeed on any other aspect of it. As a result, Commander Wally Virgo was deputed to return to Bouvourie Street to return the contents of the two envelopes to Larry Lamb, which he did on the afternoon of 16 April.

The serialisation of Biggs’s story, billed as the ‘Scoop of the Century’ by The Sun, began four days after Virgo returned the envelopes to Lamb and McConnell. Spread over several full pages each and every day between 20 and 28 April, the story certainly succeeded in selling papers.

Appearing under the banner headline ‘Ronald Biggs Talks’, the first instalment of the story began as it intended to proceed – with fanfare and hyperbole:

THE SCOOP of the century. From a secret hide-out Ronald Biggs, one of the Great Train Robbers, writes his own story of the crime, of his dramatic jail break and of his life on the run ever since. Every page of the manuscript bears his thumbprint and signature.8

The eight double-page instalments ran as follows:

April 20 – Day 1:

We Wait at the Farm

April 21 – Day 2:

Ambush!

April 22 – Day 3:

Things Begin to go Wrong

April 23 – Day 4:

On Trial: And already we talk of a crash out

April 24 – Day 5:

Going Down Fighting

April 27 – Day 6:

Wandsworth! And hell-bent for a break

April 28 – Day 7:

At Last: Over the Wall

April 29 – Day 8:

A New Face9

At the foot of each day’s instalment was a strap-line to bait readers for the next day’s revelations. Following the first day’s double-page spread on pages 17 and 18 was a box headline: ‘Tomorrow: Who Really Hit Driver Mills?’ Biggs’s apparent willingness to point the finger on this issue was one of a number of matters that would cause a degree of rancour between him and a number of the other train robbers over the decades to come. Was Biggs in fact pointing the finger? Was he actually even there at the moment when the attack on the locomotive cab took place at Sears Crossing at approximately 3.05 a.m.? This and other issues surrounding the accuracy of recollections and testimony by a number of those present that night will be examined in detail later on in this book. In the meantime, suffice to say this was not something hotly debated in April 1970.

As a result of what was a genuine and dramatic scoop that Larry Lamb had pulled out all the stops to publicise in the wider media, The Sun literally flew off the newsagents’ shelves that week, giving Murdoch his best circulation figures since issue number one on 17 November 1969. For the mass of readers who opened their copies of The Sun over breakfast on 20 April 1970, the story of the train robbery was as fresh, vivid and compelling as it had been on that August morning seven years previously, when it came over on the early morning BBC radio news.

Tommy Butler, the man who had led the train robbery investigation, and who had arguably misled the public about the outcome of the hunt, never lived to see Biggs’s story in print. He died on the very day it hit the presses at The Sun’s Bouverie Street printworks. True to form, he had kept his cards close to his chest one last time. Virtually no one knew that he had been diagnosed with terminal cancer a year earlier.

Not unexpectedly, The Sun’s ‘scoop of the century’ created a storm. Apart from the expected backlash from other Fleet Street papers that The Sun was giving cash and a public platform to a major criminal, the serialisation resulted in several major blow-backs for the Metropolitan Police. While the Yard had already battened down the hatches for the expected awkward questions and criticism that was bound to arise from Biggs’s revelations, they were certainly not expecting the fury that hit them on the first day of publication, in the shape of a full-on broadside from the Commissioner of the New South Wales Police in Sydney, Australia, Norman Allan. The New South Wales Police already had a degree of egg on their faces for letting Biggs slip through their fingers following a raid by fourteen armed officers on his Melbourne home on 17 October the previous year, only to find he had left the property only hours before. Now, to add insult to injury, the London police seemed to be hand-in-glove with The Sun, as far as the Biggs scoop was concerned.

Allan rang the Yard an hour before he was due to attend a meeting with the Australian Attorney-General, and demanded to be put through to the Commissioner, Sir John Waldron. Having been told that Waldron was unavailable, the call was put through instead to Commander Don Adams, on whom Allan let rip.10

In an apparently expletive-filled tirade, Allan expressed his amazement that New Scotland Yard ‘had supported this newspaper venture’, and felt that ‘it was holding the New South Wales force and the Metropolitan Police up to ridicule’. He promptly followed this up with a letter telexed over to Sir John Waldron, in which he:

pointed out that whilst police in both countries could not find Biggs, a solicitor had been able to receive from him his story with his fingerprints and signature. He felt that the police, by confirming the authenticity of the fingerprints were, in fact, enabling Biggs to obtain further money to assist his escape. He did not for one moment believe that any of the money from the story would be placed in a trust fund for Biggs’ children.11

Allan went on to lay into the Murdoch press, in both Britain and Australia, for ‘giving comfort and aid to an escaped prisoner’, and implied that Waldron’s force was aiding and abetting The Sun in doing so. While the Metropolitan Police file containing the account of Allan’s correspondence and telephone conversation was not to be opened for another three decades, the British public were able to hear, at first hand, a similar tirade raised by Members of Parliament from all parties on the floor of the House of Commons. The Home Secretary, James Callaghan, was subjected to a string of questions about the Biggs story at Question Time on 22 April 1970. Arthur Lewis, the Labour MP for West Ham North, waded in first, following up on two written questions he had submitted earlier that day. The first was:

To ask the Secretary of State for the Home Department, whether he has considered the information supplied to him by the honourable Member for West Ham North, showing that a newspaper has paid, either Ronald Biggs or his agents, money in relation to the mail bag robbery; whether he will take action against the newspaper concerned for aiding and abetting a convicted criminal; and whether he will make a statement.12

Lewis’s second question was as follows:

To ask the Secretary of State for the Home Department, whether he will now make a further statement on action taken to bring about the apprehension of Ronald Biggs, an escaped prisoner; and whether he will institute proceedings against Biggs and others connected with the great train robbery for the murder of the train driver.13

Papers in the closed police file show that the Home Office immediately requested that the Yard provide the Home Secretary with background notes to assist him in answering these and related questions from MPs later that day. Commander Don Adams of C2 was deputed to write briefing notes for James Callaghan:

The first question can be answered quite shortly but most authoritatively. Police efforts to locate and rearrest Biggs are as intense now as they ever were. No effort is spared to achieve this object and the authorities and indeed the general public may be assured that police activity in this direction is of a very high and persistent order.

The second question can be answered quite shortly but factually. No proceedings for murder can be taken against any of the of the persons involved in the ‘Great Train Robbery’ in relation to the subsequent death of the train driver. It is clearly defined in law that before such proceedings can ensue, the victim of violence must die within a year and a day of the infliction of same.14

Adams’s notes, drawn up with the aid of the Metropolitan Police Solicitor, were both concise and politically astute. Adams could just as easily and accurately have stated that Lewis was mistaken in asserting that the train driver had been murdered. Mills had died only a short while before, on 4 February 1970, at Barony Hospital in Nantwich. The West Cheshire Coroner had confirmed that:

Leukaemia with complications due to bronchial pneumonia was the cause of death. I am aware that Mr Mills sustained a head injury during the course of the train robbery in 1963. In my opinion, there is nothing to connect this incident with the cause of death.15

However, Lewis was a Labour MP, and Callaghan, as a Labour Home Secretary, would certainly not have wished to embarrass him on the floor of the House of Commons; neither would Callaghan have wanted to appear soft on crime in the eyes on the public by pointing out that the train robbers were not, according to the coroner’s report, responsible for Mills’s death. By answering the question on a point of law, both of these potential pitfalls were avoided.

The Yard had, of course, taken photographic copies of the envelopes they had been given by Larry Lamb, and these had then been sent to DCI Powell of the Yard’s Criminal Intelligence Section, C11, for their thoughts and analysis. Was Biggs’s vivid and descriptive tale of the train robbery and how it was planned and executed the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth? Or was Biggs, now down on his luck and next to penniless, simply spinning a cock-and-bull story to cash in on Murdoch’s famed willingness to write big cheques for big scoop stories?

What did C11 make of his account once they had the chance to line it up against the intelligence and closed file information they had at their disposal? The manuscript had, of course, been carefully scrutinised by The Sun’s lawyers prior to publication in order to avoid any obvious pitfalls that might land the paper in the hot waters of potential litigation. One example was the removing of the numerous mentions of John Daly’s name from the story. Daly had been found not guilty in February 1964 and was, therefore, in the eyes of the law, an innocent man and not a train robber.

As a result of this deletion, and a few other legal and editorial tweaks, the version that appeared in The Sun’s serialisation was somewhat shorter than the original manuscript. It was therefore the original, unedited version that C11 set about analysing.

The first thing that the Yard’s intelligence gatherers did was to pull out Biggs’s CRO file. Among the material that had been accumulated since 1963 was a copy of Mr Justice Edmund Davies’s sentencing statement:

Ronald Arthur Biggs, yesterday you were convicted of both the first and second counts of this indictment. Your learned Counsel has urged that you had no special talent and you were plainly not an originator of the conspiracy. Those and all other submissions I bear in mind, but the truth is that I do not know when you entered the conspiracy or what part you played. What I do know is that you are a specious and facile liar and you have this week, in this court, perjured yourself time and again, but I add not a day to your sentence on that account. Your previous record qualifies you to be sentenced to preventative detention; that I shall not do. Instead, the sentence of the court upon you in respect of the first count, is one of 25 years’ imprisonment, and in respect to the second account, 30 years’ imprisonment. Those sentences to be served concurrently.16

Of course, Biggs was no more or less of a ‘specious and facile liar’ than arguably anyone else in the dock of the Buckinghamshire Assize Court on 16 April 1964. However, it did underline the obvious point in C11’s mind that nothing Biggs said in his memoir could be taken at face value, without prior and established corroboration from other reliable sources. The validity of Biggs’s manuscript was hardly helped by the fact that the very first paragraph of his account of the robbery read by C11 was clearly a massive embellishment of the truth at best, and a wild tale at worst:

The fact that British Railways transport great sums of money for the General Post Office has been common knowledge to London’s criminal fraternity for many years. I first heard about it in 1949, at which time I was doing half a stretch in Lewes Prison, Sussex, for shop-breaking. I palled up with an ex-GPO sorter named Albert, who came from Middlesex – it was from him that I heard and inwardly digested practically everything there was to know about Post Office procedure.17

Biggs goes on to mention that the following year, while in Wormwood Scrubs Prison, he met for the first time another prisoner by the name of Bruce Reynolds:

During conversations with Bruce, I mentioned my friend Albert and the information he passed on to me regarding the mail train, and we discussed the possibilities of ‘having it off’ at great length … I became good friends with Bruce and our paths crossed frequently – we often spoke about ‘the train’.18

When C11 cross-referenced Biggs’s account of Albert with information on file at the Yard, and consulted Lewes Prison records, they found that Albert was:

Albert George Kitson

Born: 21 March 1928, Marylebone, London

Address: 8 Goshawk Gardens, Hayes, Middlesex.19

Far from being ‘an old post office sorter’, Kitson was in fact a 20-year-old juvenile offender, who had been sentenced to eighteen months’ imprisonment for being an accessory to a break-in at Hayes Post Office, where he worked as a clerk. According to his file, Kitson had fallen under the influence of one Cyril Edward Maunders, a 32-year-old habitual criminal known to local police and Southall parents as ‘Daddy Fagin’. Described in a report by Detective Inspector Robinson as ‘a very bad influence in the district and known as a corrupter of youths’, Maunders, together with an associate, Alan Victor Parnell (alias ‘Alan the Screwsman’), had planned to rob Hayes Post Office. Maunders had always been skilful with tools, and especially at making false keys. In the prison workshop he had developed this skill. On his release in August 1948, he sought out Parnell, and the pair ‘picked out Kitson, bought him drinks, flattered him and finally persuaded him to make impressions in modelling wax of the keys of the main post office door and the safe’. False keys were then made, and on 1 January 1949, Parnell and an 18-year-old youth named Roy Douglas Atkins entered the post office and robbed the safe of £2,760.

Albert Kitson would, it was concluded, have had no knowledge of Travelling Post Offices or TPO procedures, and it was therefore considered that Biggs’s claim to have first learned about TPOs, the amounts of money carried by them, and their lack of security could not be viewed with any great degree of credibility.

Of course, in writing his story, Biggs was stuck between a rock and a hard place. If his account reflected too much the minor role he had actually played in the robbery, there was little chance that a major newspaper would be interested in buying the manuscript for any sizeable sum of money. Alternatively, if he overplayed his hand and embellished his role too heavily, he ran the risk that on being recaptured (as he then believed was only a matter of time), a court could look more harshly on him if it was thought that he was one of the more senior members of the gang. In fact, it could be said that, if anything, his attempt at a fine balancing act possibly leant too far in the wrong direction. The recently retired Chief Superintendent Frank Williams (who had been Tommy Butler’s Flying Squad deputy) was, by 1971, Head of Security at Qantas Airlines at Heathrow Airport. He was among those who avidly read the Sun serialisation. As a result of what he read, he later commented that: ‘I admit that during the earlier part of the robbery investigation, after the fingerprints were found, I thought Biggs had been used by the gang as a reliable labourer, but I know now that he and Reynolds were two of the leading members.’20

Despite the Kitson embellishment, and a few other red herrings thrown in for good measure, did the manuscript contribute anything meaningful to C11’s already significant knowledge of the train robbery and the identities of those who took part in its planning and execution, and who had so far evaded arrest?

2

THE MISTER MEN

November 1969

IN 1834, EUROPEAN SETTLERS landed on the banks of the Yarra River in Australia, declaring the area congenial enough for a village. Soon after, the Yarra flowed through a small, haphazard settlement, surrounded by swamps and undulating countryside. In record time, a grand, well-planned city grew on its banks.

By 1969, the city of Melbourne had a population of just under 2 million. It was located at the apex of one of the world’s great natural seaports, Port Phillip Bay; southward to the horizon in both directions, the peninsulas practically joined to form an inland sea. Surrounded by 200km of beaches, this seaside playground provided almost unlimited work and opportunity for anyone seeking to make their way in the world. To the east, the Mornington Peninsula stretched like a rolling carpet of green, ending in coastal holiday communities that had been popular for generations.

Graham Kennedy, the compère and comedian, ruled the TV screens, with In Melbourne Tonight (the IMT Show) on Channel Nine, the nation’s highest-rating channel, owned by the Daily Telegraph proprietor Sir Frank Packer. Kennedy’s show, based on the US Tonight Show format, went out live every week from Channel Nine’s Bendigo Street studios, a few blocks away from the Old Melbourne Gaol, where outlaw Ned Kelly had been hanged in 1880. As Kennedy often said on the show, ‘Australians love a rogue.’

Among the workers making and dismantling the Channel Nine studio sets was a carpenter by the name of Terry Cook. Kennedy had been pressing the IMT producers for a bigger dressing room for some time; such frivolities were rarely agreed to by Sir Frank Packer’s mandarins, but eventually they grudgingly agreed. Terry Cook and three others were deputed to build the new dressing room close to the IMT set.

After Terry had left Channel Nine the following year for a better-paid job with an air-conditioning company, he had apparently disappeared. It later came out that Terry was in fact none other than Great Train Robber Ronald Biggs. Graham Kennedy made this his lead story on 17 October 1969, announcing that he was having the dressing room torn to pieces in case ‘Terry’ had hidden any of the train robbery money in the walls.

‘Terry’ saw the IMT show from the back room of a small bungalow, belonging to friends Mike and Jesse Haynes, in the Melbourne suburb of Noble Park. It was here, during the months of October and November 1969, while in hiding, that he decided to write his story. It was not the result of a considered or planned effort to write a first-hand, fly-on-the-wall account, nor was it written with the luxury of time. It did help, however, to while away the long days and weeks holed up there, while the Commonwealth Police searched high and low for him.

His plan was to finish the story of his life and have it delivered to a lawyer by Mike Haynes before the police eventually caught up with him, as he fully believed they inevitably would. The idea had sprung from the fact that his wife, Charmian, had been offered the sum of A$60,000 for her story by Sir Frank Packer’s Sydney-based Daily Telegraph tabloid. Biggs wagered that if Charmian’s story could fetch A$60,000, his own story must surely count for a whole lot more.

The most revelatory aspect of the story was that it shot down in flames a claim that had hit newspaper headlines all over the world less than twelve months before. On 15 January 1969, Chief Superintendent Tommy Butler, the man who had headed the train robbery investigation, held a press conference following the sentencing of Bruce Reynolds to twenty-five years’ imprisonment at Aylesbury Assizes. Butler opened his remarks by telling the assembled journalists that ‘Reynolds is the last of the fifteen men who robbed the train’. With the exception of Biggs, he added, all those who had committed Britain’s biggest cash robbery were now under lock and key. ‘Does this mean that this is the end so far as the Train Robbery is concerned?’ asked the Daily Mirror’s Tom Tullett. ‘No,’ Butler replied. ‘Got to catch Biggs first.’

However, according to the Biggs’s manuscript, four mystery men who had taken part in the hold-up at Bridego Bridge on 8 August 1963 were in fact still at liberty.

While we now know, from a number of Butler’s still closed written reports, that he knew full well that some of the gang had slipped through his fingers, this remained his public stance until the day he died. More mysterious is the decision by the former Deputy Assistant Commissioner, Ernest Millen, to attack Biggs in writing shortly after the publication of The Sun’s serialisation: ‘As for Biggs’s claim that four members of the robbery gang are still free men, this is sheer bunkum.’ As we shall see later on in this book, both Butler and Millen may have had other motives for trying to obscure the truth about those who got away.

For obvious reasons, Biggs chose to use aliases for the four mystery men. Recalling his first meeting with the gang in June 1963, at Roy James’s flat in Nell Gwyn Court, Chelsea, he wrote:

There I met and was introduced to 13 men, one of whom I already knew. Three of these men and another who joined the group later have never, to my knowledge, been wanted by the police in connection with the train robbery so, for their protection, I will refer to them as, Joe, Bert, Sid, and Fred.1

These four men would, in 1978, be given four new aliases in the Piers Paul Read book, The Train Robbers.2 Thanks to a later book by Ronnie Biggs & Chris Packard, this would eventually evolve into ‘The Mister Men’, i.e. Mister 1, Mister 2, etc.

While Biggs’s account was written six short years after the robbery, the events of 1963 were still relatively fresh and clear in his mind. The original seventy-seven handwritten pages were typed up by Jesse Haynes and eventually sold to Rupert Murdoch’s Australian tabloid, the Daily Mirror, and syndicated to The Sun in London.

By late 1969 the other convicted robbers were already six years into their sentences. There had been no collusion or contact between Biggs and the other robbers since their Court of Appeal hearings held between 10 and 14 July 1964. The manuscript was therefore based entirely on Biggs’s unaided and uninfluenced recollection of events, albeit with a few changes here and there to avoid getting himself into even hotter water should he be arrested in the near future.

As noted in the previous chapter, for understandable reasons Biggs had walked a tightrope in not over- or underplaying his role in the robbery, so far as the manuscript was concerned. He therefore sought to airbrush out the role he had played in recruiting an alternative train driver, and maintained that he had joined the gang before the decision to find another driver had been taken in June 1963. Recalling a planning meeting held at Roy James’s flat in Chelsea, Biggs recalls the debate:

‘As we stand at the moment, our only problem is pulling the train after we’ve stopped it,’ said Reynolds.

‘I still say we can make the driver do it,’ broke in Goody.

‘Suppose he refuses,’ objected Buster.

‘Make him.’

‘How?’

‘Frighten him!’

‘Suppose he doesn’t frighten – suppose he has a heart attack!’

‘Why don’t we get our own driver?’ Bert asked. ‘I know an old bloke who, I think, might be interested.’

‘Even if he was interested and brought in,’ Roy protested, ‘he would still be an “outsider” and a danger to all of us. Apart from that, do you really think a straight man would have the nerve? You must be joking!’

The point was debated until, once again on a show of hands it was decided that Bert should go ahead and, if possible, procure the railway man’s services and, at a subsequent ‘meet’ we were introduced to a cheerful, old (sixtyish) train-driver named Fred. He had been approached at his local pub by Bert, who had offered him £20,000 to drive a diesel train for a short distance ‘sometime in the future’. Fred had been only too pleased to oblige, and he intimated he would drive a train to Land’s End for £20,000.3

Having shifted his responsibility for recruiting Fred the driver from himself to Bert, Biggs, from there on in, tells the story pretty much in line with other subsequently corroborated sources.

What, then, does Biggs’s manuscript tell us about Joe, Bert, Sid and Fred and the respective roles they played in the robbery?

According to the original manuscript:

It was decided, that our arrival at the farm should be staggered so as not to arouse suspicion. It was arranged that Bruce, Jim White, John Daly, Bert, Fred and myself would travel in one of the Land Rovers early on the morning of the sixth of August. Buster, Jim Hussey, Tom Wisbey, Bob Welch and Joe would arrive in the truck about 9.00 p.m., and Charlie Wilson, Roy James and Sid in the second Land Rover about 10.00 p.m. Goody was to remain at the house of Brian Field in Pangbourne for a telephone message from our ‘man up North’ which would tell us when the ‘holiday money’ was on its way to London.

At 9.00 a.m that same day, Biggs recalled:

I climbed into the back of one of the Land Rover which was parked near Victoria Station; the others were already there, and with Jim White driving we set off for the farm in Buckinghamshire. The journey was a cheerful one. We were in good spirits and my ‘windfall’ of the previous day was regarded by all as a good omen.

‘You’ll be able to buy us all a beer on the way back!’ laughed Fred.

The many moments of humour provided by Fred were mostly unintentional and often he would ask, ‘What are you laughing at?’ Strictly speaking, he was an honest man and he was extremely naïve about the magnitude of the operation he had entered into. During the journey he asked who the Land Rover belonged to, and when he was informed that it had been stolen, he exclaimed, ‘My lord! I hope we don’t get pinched!’4

As Biggs indicates, Fred was not a career criminal; in fact, he was not a criminal at all, but a former British Railways engine driver. Already there are telltale clues early on in the manuscript that Fred is exceptionally naïve at best, or at worst, a man with possible mental health issues.