26,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: novum pro Verlag

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

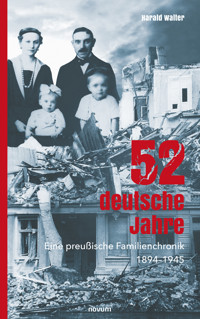

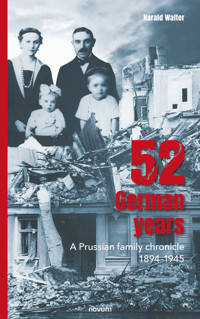

1895-1945: An exciting family saga spanning 5 decades The decline of the German Empire and the Weimar Republic, the Roaring Twenties, the bitter course of the Third Reich: a Prussian family is thrown back and forth over two generations by the political turmoil and dramatic events. Otto and Käthe Waischwillat, and later their two daughters Waltraud and Kriemhild, desperately try to keep their heads above water. In the uncertain times between 1894 and 1945, this meant a constant balancing act between love and renunciation, between fleeing and fighting, between morality and the fulfillment of duty. Will the family manage to steer their lives in the right direction?

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 1222

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

Harald Walter

52 German years

I dedicate this book

in Memoriam

to the grandparents' and parents' generation

of my family,

who in most difficult times

The imperial years 1894-1914

1894 Deeden in East Prussia - a sad birthday

Otto had imagined his seventh birthday differently. There had been the eagerly awaited cup of hot chocolate and the thickly buttered jam sandwich for breakfast. And the fervently desired fur hat and a pair of brand new winter boots had been hastily placed next to the thick candle on the kitchen table, but the cozy get-together with his parents and the maid Svetlana had been missing, because his mother Wilhelmine had immediately disappeared back into the bedroom, where Otto's father was fighting for his life in bed. Svetlana waited in the hallway outside the bedroom for any instructions, such as fresh damp cloths for the large farmer's feverish forehead or fresh water or bricks warmed in the kitchen stove. Friedrich, her husband, house servant and coachman, stood helplessly beside her at the top of the stairs. Grandfather Johann Mohn, Wilhelmine's father, had been at his daughter's and son-in-law's side since yesterday. Doctor Rosenbaum from Stallupönen had also returned, a stout, bearded man with a red face whose deep voice could be heard all the way into the kitchen. His horse was still steaming in front of the house, having just wrapped the reins around one of the thin trees that flanked the steps leading up to the bay window entrance of the wooden two-storey manor house.

Otto was now sitting on this staircase, wearing his new fur hat and the tattered winter jacket with sleeves that were already too short, which he wanted to replace for the coming Christmas. It was bitterly cold on Thursday, December 15, 1894, as cold as he was used to every December in his East Prussian homeland. A piercing easterly wind swept over the thick blanket of snow, piling the flakes into mountains behind every obstacle. Otto had already noticed that his mother, grandfather and Svetlana had been very worried for days.

On the last Sunday lunchtime after the meal, his father had set off, as he did every Sunday, with the sleigh in a thick snowstorm to nearby Stallupönen for a morning pint, but had not returned for supper as usual. This had happened several times before and so Otto and his mother waited patiently at the table. But when the groom Arthur Adworeit rushed excitedly into the kitchen with the words: "The sleigh is back, without the gentleman!", the excitement was great. Actually, the five kilometers of road to Stallupönen were dead straight and the country road then continued via Insterburg to Königsberg, but occasionally Otto's father did not take the road, but the unpaved path next to the railroad line 400 meters away, on which the long-distance rail traffic ran from Berlin via Königsberg to the nearby Russian Empire. In the snowstorms of those days, the railroad embankment was often a better guide than the country road, which was covered in high snowdrifts. And it continued to snow incessantly, it had long since been pitch dark and the icy wind made the flakes dance.

Otto's mother was a stocky thirty-year-old woman whose broad cheekbones and strong chin betrayed her Slavic ancestry. She didn't hesitate for a minute, but gave the order for Friedrich and Arthur to search the path with the horse-drawn sleigh.

"He will have taken the path by the railroad embankment. The horse knows it best," she said in a firm tone.

They both put on their thick winter furs and caps, slipped into their sturdy boots and strapped on snowshoes. Arthur lit a kerosene storm lamp while Friedrich turned the horse-drawn sleigh around and took the horse by the reins. Then they both stamped off towards the railroad embankment. They could still see traces of the sledge in some places, so they were right in their assumption that the farmer Georg Waischwillat must have chosen the way back along the tracks. The flickering light of the kerosene torch offered little visibility and there were always waist-high snowdrifts to cross. Their progress was very slow.

"Man, man, man!" Arthur kept muttering to himself, so that Friedrich finally told him to shut up or his tongue would freeze. It took them almost twenty minutes to walk the few hundred meters to the railroad embankment. When they reached it, they were able to turn west and make better progress. The harsh north-easterly wind had swept the northern side of the railroad embankment empty and piled up high snowdrifts on the southern side. Only in the lee of occasional bushes did they have to struggle forward again. They reached the point where the railroad embankment is crossed by one of the tributaries of theTrüberiver, which meanders northwards in ice-free periods. Here, the accompanying path normally sloped steeply down to the stream, but the depression was now completely filled with snow, with only a hint of the sledge tracks from the return journey still visible. But at one point on the other bank, Georg Waischwillat's fur hat was sticking out of the mass of snow! The heavily inebriated farmer had probably fallen from the coachman's seat as the sledge slid down into the hollow. Friedrich stopped the horse while Arthur was already digging through the snow above the frozen stream and began to shovel his breadwinner free with constantman, man, man.

The large farmer's bearded face was covered in a layer of ice, the moist air he breathed had crystallized immediately in the temperatures of around minus 30 degrees Celsius. He rattled, but otherwise remained completely motionless. Both rescuers only hoped that his thick fur coat, sturdy gloves and fur boots had been able to protect him from the worst of the frostbite. With their combined strength, they pulled the motionless man to the other side of the stream and heaved him onto the low loading area of the sledge. Then they turned around and, holding the horse by the reins, trudged back to the estate the way they had come, which was already virginly covered in snow.

Wilhelmine had already prepared everything there. She had warmed the bed and laid out fresh nightclothes. Svetlana, who also acted as cook, prepared hot herbal tea with a good shot of brandy.

The large farmer was stocky and muscular, but not a giant. So the two men managed to carry him up the wooden stairs to the second floor bedroom and sit him on the edge of the bed, where Wilhelmine and Svetlana freed him from his frozen clothes and heaved him into bed. They rubbed his hands and feet and then wrapped them in warm towels. Obviously the alcohol had kept the blood flowing to his limbs. However, the great danger of the drunks was that they cooled down more quickly overall. The attempt to pour him warm tea failed at first, so they covered him up to the tip of his chin and weighed down the blanket with warm bricks wrapped in cloths. The farmer let all this happen to him and apart from an occasional rattle, during which he blew out a strong plume of alcohol that could have been set alight, he made no movement.

The Sunday pint with his friends from the neighboring farms and villages must have been particularly intense this time. They probably discussed politics at length. After all, Kaiser Wilhelm II had just appointedthe 75-year-oldChlodwig zu Hohenlohe-Schillingsfürst as thenew Imperial Chancellor at the end of October, whose competence to speak his mind to the Kaiser was highly questioned. And just ten days earlier, the Emperor had inaugurated the new Reichstag in Berlin with much pomp. The building is said to have cost more than 20 million Reichsmarks. There were also plenty of other local political topics, and each one was always washed down with a glass of brandy and strong beer.

Wilhelmine spent the rest of Monday night at her husband's bed. Svetlana didn't get a good night's sleep either, as she had to replace the cooled bricks and provide fresh hot tea every few hours when the farmer finally got up.

In the morning, it seemed as if he would recover and, like all the many intoxications before, would cope well with this one too. But when he tried to get out of bed, he broke out in a cold sweat, his breath stopped and he sank limply back onto the pillows.

Wilhelmine, who had dozed off in the chair next to the bed, startled. "For God's sake, Georg! Stay down! Cover yourself up. I'll send Friedrich for Dr. Rosenbaum!" She stumbled sleepily down the stairs and called the servant and coachman, who had his room with his wife Svetlana in the basement.

"Friedrich! Take a horse and get Dr. Rosenbaum! Quickly. Hurry up!"

Friedrich slipped into his fur jacket, put on his cap, stepped into his heavy riding boots and left the house with a clatter. He fetched one of the heavy riding horses from the stable, saddled it up and galloped as far as the snow cover would allow to Stallupönen, four kilometers away. The Jewish doctor Dr. Rosenbaum, who was a good friend of the large farmer, was sitting at breakfast, downed his cup of coffee, took another bite of the cheese sandwich, packed his heavy doctor's bag and saddled his horse. He followed Friedrich back to Deeden in a thick coat.

He found his friend in a frightening state. Short of breath, coughing up phlegm and with beads of sweat on his forehead, the master of the house lay in bed like a heap of misery. Dr. Rosenbaum acted quickly, listened with a stethoscope, tapped his chest and back, checked his flaccid reflexes and measured his increased pulse and high fever. The women carried out his instructions immediately. Hot mashed potatoes in a linen bag on his chest, cool compresses for his forehead and calves and a bowl of hot eucalyptus water, the steam from which was to be fanned on him. With the promise to come back tomorrow, he set off for more house calls. A strenuous undertaking in these arctic temperatures.

Georg's condition did not improve as the day went on. The two women tirelessly alternated hot and cold applications and infused him with peppermint tea with thyme and honey. On the evening of Monday, the master of the house fell into a deep sleep, which was repeatedly interrupted by coughing fits and snoring. This was also the case on the following Tuesday and Wednesday.

Dr. Rosenbaum administered several more drops, which he dripped into her nose and mouth. He took Wilhelmine to one side. "It's pneumonia with severe catarrh, but Georg is a strong lad. He has to get through it, he'll make it!"

His condition was no better today, Thursday, and he had even fantasized aloud during the night, repeatedly interrupted by snoring coughs and wheezing.

As a result, Otto's birthday was treated as a minor matter and he retreated to the stairs of the manor house, shivering. At the age of seven, he had already witnessed the deaths of his paternal grandparents. He had not been allowed to visit their deathbeds so that he could say goodbye, but he had been able to see them again when they were laid out in the hallway of the house. His grandparents had been very old and had been ill for a long time; they had rarely left their retirement home at the end of the main house. Now he only had his maternal grandparents, Johann and Wilhelmina Mohn, innkeepers in Pöwgallen, twenty-five kilometers away.

Otto looked pensively at the dwindling snowflakes when Svetlana came out of the door, sat down next to him and wrapped the thick woolen shawl she was wearing over her shoulder around his back. Otto leaned his head against the left of her firm breasts. He had been fascinated by them for as long as he could remember.

Svetlana was the formative female figure in his young life, more so than his own mother. A decade ago, at the age of twelve, she had come across the nearby border with a troop of Mushiks, Russian-Lithuanian harvest workers, to help out with the sowing and later with the harvest, as she did every year. This had become necessary because many farm workers, but also second-born sons of farmers, were lured to the industrial areas of Silesia and Saxony, which had earned them the name "Saxonians". Svetlana was already very well developed for her age and had immediately aroused the interest of Friedrich, who was going through puberty at the time. Two years later, the seventeen-year-old lad had impregnated her behind a haystack in the spring. The enraged farmer demanded that Friedrich marry the girl. In the same year, Wilhelmine had also been pregnant with Otto. As fate would have it, the now fifteen-year-old pregnant girl lost her child in November 1887 in the seventh month and shortly afterwards her mistress was delivered of a healthy boy. Svetlana took over the breastfeeding and care of little Otto and thus got over the greatest pain of her own loss, while her mistress was able to return to the orderly business of the Waischwillathof. The act of breastfeeding developed into an addictive process for Svetlana. When little Otto's first sucking reflex caused milk to flow into both breasts, waves of lust ran through her whole body. Her husband Friedrich knew how to enjoy this tenderly.

Svetlana breastfed her surrogate child for over two years and was provided with better food than the other servants. Later, she read Otto stories, sang Russian and German songs and taught him the Russian language at an early age.Lanawas his first word even before he saidMama.The maid Svetlana had a different nature to Otto's mother, the reserved, cool mistress of the house, who communicated with a deadpan face and terse words and rarely let any emotion show, not even to her young son. Svetlana, on the other hand, could not hide her feelings; everything could be read in her face and posture, joy and sadness, astonishment and compassion. Otto could still remember the times when he would sit on her lap and press his nose between her plump breasts or when she would carry him around astride her broad hips during other tasks, which even then had triggered an irritating, beautiful feeling in him. He also loved Svetlana for always having a little treat ready for him in the kitchen. Otto had had a carefree childhood so far. He also had his father to thank for that, who was very different from his mother and played and went fishing with him when he had time.

"Does Dad have to die?" he asked anxiously.

"Your father is a strong and capable man. He won't give in to pneumonia," Svetlana replied, gently stroking his cheek. In silence, however, she was no longer sure of this, because the great farmer had become weaker and weaker and had hardly been able to breathe the last time she had been able to take a look into the room. Wilhelmine had held his hand with an unmoving face, Johann Mohn, her father, had helplessly stroked his daughter's arms and the doctor had repeatedly listened with the wooden stethoscope for the rattling sounds of breathing. The humid air in the room smelled of eucalyptus, mint and sweat.

"You should go back to the kitchen now, otherwise you'll catch a cold too," she said and stood up. "I'll make you another chocolate."

Without a word, Otto got up and followed her through the porch and hallway into the kitchen, which was cozy and warm thanks to the often-used stove. Svetlana poured milk from a jug into a saucepan, added two spoonfuls of cocoa powder and a good spoonful of honey and placed the pot on the stove top, where it heated up with a crackling sound. Then she poured the steaming cocoa into Otto's ceramic mug. Otto warmed his clammy fingers and carefully sipped his beloved drink.

And so the hours of his birthday passed. Svetlana was called again and again and had to get this or that, fresh laundry, hot or cold water or herbal tea for the exhausted helpers. She also had to reassure the worried employees of the farmer, who kept knocking on the door and asking about the condition of their employer.

*

Georg Waischwillat's farm was one of the larger of its kind with its 105 hectares of land and seven registered fireplaces. There were three families, so-called Instmann families, plus Arthur Adworeit, the stable master with his wife and two daughters, the master milker Adolf Wauszkies and finally coachman and servant Friedrich Memel with his wife Svetlana. In contrast to the large noble estates, which often had more than a hundred employees with a wide variety of skills, several servants worked on the Waischwillatsch farm at the same time. For example, the farmhands mainly carried out manual tasks in winter, while their wives did the gardening, looked after the poultry and helped milk the cows.

The soils on the northern edge of the Rominter Heide in the Pissa lowlands were only partially suitable for growing rye or potatoes. Their yield was often not sufficient for much more than their own needs, so Georg specialized in dairy farming and had already had modest success in breeding and selling animals at the market in Insterburg. This was due to his father Michael Waischwillat, who had received a good settlement when his estate was cut through by the construction of the Königsberg - Eydtkuhnen railroad line in the 1950s.

All the employees' families had free apartments in the two large rectangular buildings flanking the main house, which also housed the stables for the animals. Each employee was allowed to keep a pig, plus chickens and geese, and received fixed rations of grain, potatoes, firewood and brushwood, and each had a small plot of land on which they were allowed to grow vegetables and fruit, although some of this had to be given to the employer if required. As their cash wages were only around 20 marks a month, the employees earned additional income by selling eggs, milk, butter, poultry and bacon. The system was one of family togetherness, full of respect for the big farmer. There was no aristocratic or aristocratic-elitist attitude on the farm.

In addition to 60 dairy cows, each of which already had an annual milk yield of over 3,500 kilograms, there were six draught oxen and ten cold-blooded horses, which were either ridden or harnessed to carriages and sleighs. They were more frugal and more stable than the famous warmbloods from nearby Trakehnen, which were already famous far beyond the borders of East Prussia.

Also indispensable were the four farm dogs, all mongrels, which guarded the poultry enclosures from foxes and wolves, and an unknown number of cats, which kept the mouse infestation in the apartments and stables in check.

Friedrich and Svetlana had the respect of all the other employees due to their position and apartment in the main house and so Svetlana was always able to calm the worried people down and get rid of them.

*

Otto sat at the kitchen window and looked across the snow-covered country road to the distant railway line, where an illuminated express train, smoke rising from its chimney into the now starry sky, was heading towards the Russian border. In the ice-free months, Otto loved to sit close to the railroad embankment and watch the black steel horses, dreaming of traveling away from Deeden with them. To St. Petersburg, for example, to visit the Russian tsar that Svetlana had told him so much about. Or to Königsberg, where Otto had already been allowed to accompany his father once. Otto also liked to dream of visiting the imperial capital of Berlin and the German Emperor Wilhelm II. The stable master's brother was a railroad inspector, so Arthur always knew a lot about the technology and the rail network. That the tracks of the German Reichsbahn had a gauge of 1435 millimetres, whereas the Russian tracks were 1520 millimetres wide, and that passengers therefore had to leave the train behind Eydtkuhnen at the Russian border and change to the other carriages. Prestigious railroad stations had been built on both sides of the border to give travelers a good impression. Thanks to his brother, Arthur was also familiar with the latest locomotives; the S2 express train tender locomotive had just been replaced by the new S3, which, believe it or not, would reach speeds of one hundred kilometers per hour. Otto felt dizzy at the thought and wondered whether such a speed could be healthy at all.

Suddenly he was torn from his thoughts by a terrible cry.

"No, no, no! Doctor, please tell me it's not true!" Otto's mother stood in the bedroom doorway on the second floor and could no longer hold herself up. She sank to the floor, sobbing. Grandfather Johann tried to get her up, but only succeeded together with Dr. Rosenbaum. Svetlana stood there with a horrified face and both hands in front of her open mouth.

Otto had never seen his mother so upset. "What about father?" he asked anxiously. No one heard him. "What about father?" he shouted.

Svetlana spotted him, hurried down the stairs and hugged him to her. "You have to be very brave now, Otto, very brave. Something very bad has happened. Your father didn't make it. It's terrible, but unfortunately he didn't make it. It's very sad. Your mother is very sad. We are all very sad."

While Svetlana talked to Otto, Otto's little head was spinning with thoughts. His father dead? That can't be! Why? The doctor came to make his father well again. What has happened? Is his father going to heaven now? Who will go riding with me in the summer, Otto asked himself. And who will make him the new fishing rod he was promised? And what about mom? Is she going to die too? She fell down after all.

"Is mom dead too?"

"For God's sake, no! Mom is just sad, very sad. Just like all of us." Svetlana pulled Otto into the kitchen with her. There she took him on her lap and hugged him. He couldn't enjoy it this time.

*

Georg Waischwillat's funeral was held the following Sunday with great participation from the surrounding farmers and craftsmen. Wilhelmine, her parents Johann and Wilhelmina Mohn and all the servants were dressed in black and bid farewell to the large farmer who was laid out in the hallway. The instalments, milking master Adolf, stable master Arthur and Friedrich carried the coffin down the steps and joined the mourners waiting there to solemnly walk with them to the farm's own cemetery, where a pit had been dug under the family cross. The priest from Stallupönen gave a moving speech that brought tears to the eyes of many of the mourners. Georg Waischwillat had been a popular employer, treated his people decently and had visions for his time of how East Prussian agriculture could develop progressively and prosper. He was not a political man, but was always interested in what was happening in faraway Berlin. He had had a close group of men with whom he had been on friendly terms, including the doctor, the priest and the blacksmith from Stallupönen.

At the end of the moving speech, everyone said the Lord's Prayer. After the priest had thrown a small shovel of earth onto the lowered coffin, Wilhelmine and her parents did the same, followed by Otto and then all the mourners. Otto was later unable to remember how many people had shaken his mother's and his hands as they passed by; he experienced these hours of saying goodbye to his beloved father as if in a trance. As he and his mother followed the mourners to the house, the instagrammers grabbed their shovels. While the guests gathered around the coffee table in the large hallway and feasted on apple pie and brandy, Otto sat on the stairs to the upper floor in a daze. He was irritated by the fact that the round table was getting louder and livelier. He retreated to his small room, lay down on his bed in full costume and covered his ears. And fell asleep.

*

"Otto!"

Otto opened his eyes. Svetlana was standing at his bedside, leaning over him. He had been sleeping soundly and dreaming that the teacher was calling him to the blackboard.

"Wake up! It's late! Friedrich is waiting with the sleigh! You have to go to school!"

Otto looked down at himself. Slowly, the memory of yesterday returned.

"Thank God you're already dressed," said Svetlana. "I've made you some warm milk and a sandwich! Hurry up. You know the teacher doesn't like it when you're late."

Otto slipped into his boots and followed the maid down to the kitchen. There, standing up, he sipped a mug of warm milk, put the lunch box in his satchel, which Svetlana had already prepared, and let himself be helped into his thick winter jacket, which had become a little too small last year. He stumbled out with his fur hat askew and climbed onto the coachman's seat with Friedrich.

"Your gloves!" Svetlana shouted and threw them at him.

Friedrich caught her, released the horse's reins and cracked the whip. The sleigh set off with a jerk. The sky was clear, the temperature icy. The road to Abtsteinen showed the tracks of sledges that had already made their way towards Eydtkuhnen that morning, Friedrich knew how to use the ruts so that they made good and fast progress. If there was little or no snow on the way to school, Otto always walked.

The one-grade school was located on the edge of the small village in a building with brick walls and a wooden superstructure. Otto's teacher, Richardt Bliesath, was an old man who had been a widower for a long time and had his living quarters right next to the schoolroom. His seven pupils were between six and ten years old and came from the farms in the surrounding villages. Otto hurried into the classroom. All the other children were already there, including Svenja, the nine-year-old daughter of the master of Melk, whom he secretly adored. All eyes were on Otto.

"You're too late, Otto!" scolded teacher Bliesath, nasally. He was always nasally, which was probably due to the pincher that was always perched on the lower third of his nose. When the teacher got strict and loud, the thing sometimes slipped off his nose to the quiet delight of the children, but this time it held, so he probably wasn't particularly angry about Otto being late.

Otto began to stammer an apology, but Mr. Bliesath interrupted him: "For the sake of your bereavement, I will put mercy before justice today. Sit down!"

Otto crept to his seat, took off his gloves, dug his slate and pencil out of his satchel and placed them on the bench in front of him. Like the other children, he kept his jacket on because the classroom was not heated. Teacher Bliesath also wore his thick winter coat, printed with brown checks and patched with leather at the elbows and collar. The coat hid his scrawny figure, which reminded the children in the snow-free months of the figure ofTeacher Lämpel fromWilhelm Busch's bookMax and Moritz.

Like many teachers in the villages of East Prussia, Mr. Bliesath received only a modest salary and lived mainly from the gifts he received from his pupils' parents - eggs, bread, meat, fruit and vegetables. It was said in the villages that Mr. Bliesath had been seriously wounded as a young non-commissioned officer in the war between 1870 and 1871 and had then been given the post of teacher with the prospect of a modest pension in recognition of his bravery. Nobody knew what wound he had sustained. Even at the regulars' table, they had not been able to elicit it from him. Teacher Bliesath always spoke highly of his pupils and of atreasure that had to be well guarded: "The children's curiosity is a treasure that has to be preserved. If they lose their curiosity, then a teacher no longer has a chance." For this reason, he was probably popular with the children despite his strict demeanor and was able to teach even the biggest bullies something.

"Good morning, children!"

"Good morning, Teacher Bliesath!" the children replied in chorus.

"In our first lesson, we want to repeat how to write the alphabet in upper and lower case. Get your pens ready!" He leaned with both hands on his desk, which creaked under his weight. The teacher's breath condensed into a white cloud, as if he were smoking a cigar.

The lessons took their usual course and all the children were busy with their various tasks, which Mr. Bliesath constantly checked, strutting from one pupil to the next. Sometimes he would tap one of his pupils' desks with his cane if there was something to correct or if someone was chatting. However, he never used the cane as a punishment, as was common in many other schools. And he attached particular importance to the fact that the children did not speak the Low German/East Prussian dialect in class, but, as he used to say,the Hannöverdialect.

"If you want to become something in the world, you have to use cosmopolitan language," he often said, and for this reason he brought along a read-out edition of theKönigsberger Allgemeine Zeitungevery week, from which the children then had to read aloud.

The morning's lessons passed quickly, and when the bell from the nearby church tower struck twelve times, all the pupils hurriedly packed up their slates and pencils, said "Goodbye, Teacher Bliesath" and rushed out, where they were already awaited on the forecourt by their parents' mothers or fathers or employees. Svenja was not picked up. Friedrich and Otto took her with them. Otto had had a crush on the pretty girl with the long blond braids since last summer. When she sometimes looked at him in class with her blue eyes, he felt a blush creep into his face and quickly looked away. But he was far too shy to approach or even speak to the two years older girl. Now on the bench of the carriage, she slid a little closer to him.

"Are you sad?" Svenja asked him cautiously.

Otto, who had only been thinking about Svenja for the last few minutes, had to think for a moment about what she meant. When he remembered, he suddenly felt sad. He nodded to himself and felt Svenja's gaze on his face.

"I think so. I loved father."

"We've all had that," said Svenja and briefly placed her hand on his forearm. Otto wished she would never take her hand away. He looked to the side so that Svenja couldn't see his tears.

"Have you got schoolwork?" Friedrich intervened and brought the two of them onto an unpopular topic. The sleigh turned into the farmyard.

*

During the Christmas holidays, the mood was gloomy. Friedrich had put up a Christmas tree in the living room, as he had done every year, and Svetlana had lovingly decorated it with wax candles and baked goods, but neither Otto nor his mother could really enjoy it. Even the long-awaited new winter jacket didn't cheer Otto up. He missed his father especially when he thought about Christmas evenings in the past: the family had sat together in the living room in the warm light of two oil lamps. His father in his heavy wing chair, which still belonged to his grandfather Michael. Otto at his feet on a footstool. His father had patiently answered all his many questions, taking a puff on a thick cigar or a sip of brandy in between. Otto's favorite questions were always about theThree Emperors' Year. It was the year after his birth, in which the old Kaiser Wilhelm I died at the age of 90 and his son Friedrich III took over the regency for 99 days, during which time he could only communicate with his government in writing because he had been seriously ill with throat cancer. When he died, his son William II assumed the throne on the same day at the age of 29. While William I is said to have been a popular but conservatively strict regent, Frederick III was said to have liberal ideas, which he was unable to assert against Chancellor Bismarck during his short reign. Wilhelm II, however, was an idiosyncratic and self-absorbed personality. He despised his father's liberal ideas and developed a penchant for pomp and the military. He quickly parted company with Chancellor Bismarck, who was far too authoritative for him. Otto's father strongly condemned this and shared the opinion that prevailed among the people about the three rulers: "Wilhelm I was the old emperor, Frederick III the wise emperor and Wilhelm II the traveling emperor." The latter loved to present himself in the provinces of his empire and to travel to his relatives of the European high nobility in England and Russia. Only two years earlier, in the summer of 1892, the pompous imperial yachtHohenzollernhad been launched at the Vulcan shipyard in Stettin. But Otto was also fascinated by the stories of the victorious battles against the French in 1870 and 1871, after which the Prussian King Wilhelm was crowned as German Emperor Wilhelm I in the fairytale palace of Versailles, or the stories of the German-Danish War in the 1860s, in which Prussia wrested the Duchies of Schleswig, Holstein and Lauenburg from the Danish King with the help of Austria. Afterwards, the two major German powers were unable to agree on the distribution of the spoils and the organization of the fragmented German state landscape and went to war against each other. Even then, the Prussian troops and their allies remained successful and defeated the Austrians at Königgrätz in 1866. It was only thanks to the skilful negotiating of Chancellor Bismarck that all opponents initially agreed to the armistice in the so-called Peace of Prague without any loss of honor.

Otto had absorbed all these stories. He loved the small collection of tin soldiers from the Prussian and Austrian garrisons that he had received as a gift from his father and, when he was allowed to, reenacted the decisive battles in the drawing room or in the kitchen, enjoying it immensely when the Prussians emerged as glorious victors over the Austrians. Otto kept a martial picture of the storming of the Düppel entrenchments, which his father had cut out of the newspaper many years ago, like a treasure in the drawer of his little table in his room.

With a childish shudder, he was also told about the German colonies in southwest and southeast Africa, about the fact that there were supposed to be Moors there, people with black skin, like in the children's bookDer Struwwelpeter.Otto knew that it was precisely this story that was always read to naughty children. It wasn't like that with Otto. He always tried to be good. That was also something he probably had to thank his father for.

Otto's father Georg, born in 1853, had not taken part in any of the wars because he was still too young to do so. However, he had received a strict upbringing and had been taught the typical Prussian virtues of Protestant-Calvinist morality, which Kaiser Wilhelm I in particular had repeatedly propagated.Prudence and wisdom, bravery, courage and moderation - as well as justice, supplemented by the Christian virtues of faith, love and hope - had been taught to him as particularly desirable. And he endeavored to pass them on to his son Otto. Lying was out of the question for Otto from an early age if he was caught doing something wrong. He soon got out of the habit of being stubborn or throwing tantrums after they were punished by being grounded. Otto was never beaten by his parents.As a two-year-old boy, his father had already put him on a horse, and Otto had since become a passable rider. For his fifth birthday, he was given a small Panje horse called Matusch, which brought him great joy. However, since his father's death, Otto could hardly be bothered to look after his beloved horse, but mostly sat idly in the drawing room leaning against the wing chair, not even feeling like leading his tin soldiers into a victorious battle.

Support is needed

Even after the turn of the year, nothing changed in the depressed mood. Otto's mother and Svetlana were busy with the women of the Instleute doing what they called their Weiberwinter chores - butchering and plucking poultry, splicing feathers, stuffing down, mending bedding and clothing, curing meat, sausaging, churning butter, baking and much more. Normally it was always an entertaining affair, with lots of joking, swapping the latest stories and plenty of brandy. But this winter, none of the women dared to be cheerful in the company of the grieving landlady. They all diligently performed their duties and then retired to their families. No one dared to attend the winter balls with which the farmers and craftsmen traditionally welcomed the New Year in Stallupönen or Eydtkuhnen. These were bleak weeks in which the stocks of brandy in individual homes dwindled faster than usual. To make matters worse, everyone was worried about what would happen to the farm after the death of their master.

The fields and meadows were still covered in snow, but March was approaching and soon the fields would have to be tilled and the cattle driven out to pasture.Wilhelmine was seenless and less often in her black mourning clothes. Otto's grandparents were also worried about the farm. They knew that a solution had to be found to ensure the continued existence of the large farm, and they had a plan.

On a sunny Saturday morning at the end of February, Johann Mohn turned up in his sleigh in Deeden and invited his daughter Wilhelmine and his grandson Otto to his inn in Pöwgallen for a coffee and an overnight stay. Wilhelmine didn't feel like company, but she didn't have the heart to refuse her father's well-intentioned offer. Otto was very happy about the upcoming change. Pöwgallen was a village southeast of Tollmingkehmen on the northern edge of the Rominter Heide and belonged to the administrative district of Goldap. Otto's grandparents ran the local inn there, which offered rooms for rent in addition to its large restaurant, which was good business as the heathland was a popular hiking area for the wealthy middle class from Königsberg. The proximity to theRoyal Prussian Main Stud Trakehnenalso brought in many a well-paying guest.

It hadn't snowed in the last few days, so the sledge covered the 25 kilometers at a brisk trot in two hours and they arrived at the inn in the early afternoon. Wilhelmina Mohn was already standing in the driveway, helped her daughter off the sleigh and hugged her in silence for a long time. Johann Mohn handed the reins to the farmhand.

"Take care of the horse and bring our daughter's luggage to thelarge parlor." Thelarge parlorwas the best guest room with a view of the Rominter Heide.

Coffee was already steaming on the table in the dining room. Otto's grandmother had baked a juicy apple pie, which she knew her grandson in particular loved. After everyone had warmed up and fortified themselves, the innkeepers got down to business.

"We're very worried," Johann began. "What will happen to the Waischwillatfarm?"

"I don't know, Father. My head doesn't feel like it yet," Wilhelmine defended herself.

"But you have a responsibility! The people on your farm expect you to make a decision," replied her mother.

"But I don't know anything about crop rotation or dairy farming. Georg has always taken care of the business. I wouldn't know how to familiarize myself with all that. And if I did, whether people would take me seriously. Because I'm a woman."

"Then we need a man," the father said loudly. "Someone who understands farming."

"A man?" Otto's mother asked, beside herself. "I've only just completed two months of mourning. And now a man is supposed to move into my house? What will people say?"

"He doesn't have to move in with you straight away," her mother interjected. "He just has to sort out the business for the spring."

"Mother! Where would this man come from? And even if one did come, I'm hardly in a condition at the moment for him to find me attractive!"

Wilhelmine was in tears. It irritated Otto because he had rarely seen his mother stunned. The last time was on the anniversary of his father's death.

He understood that his mother was crying now, because Otto didn't want a strange man in the house either. He didn't want a new father. He wanted his father back or none at all. He had his mother and Svetlana. That was enough. For a while, it seemed as if the adults had forgotten that he was sitting at the table and following the conversation. Now his grandmother's eyes turned to him.

"Boy, are you full?"

Otto nodded.

"The sow has had five piglets. Would you like to see them? Come on, I'll show them to you!" Without waiting for an answer, the grandmother grabbed Otto's hand and pulled him outside with her.

As soon as they were out of the door, Johann Mohn leaned over to his daughter and whispered: "You've only just passed your thirties, you're attractive and you've got a lot to offer!" He paused before continuing. "And we have the man you need right now."

Wilhelmine backed away. "I can't believe it! So that's the reason for this invitation! You're in a great hurry!" She got up and walked up and down the room.

"But Wilhelmine, understand that we care about the fate of your farm. We care about your existence! Just take a look at the gentleman."

Wilhelmine was breathing heavily, her hands clenched on the back of the chair.

"We could invite him to dinner tonight without any obligation," her father continued insistently. "And then you can think about everything in peace afterwards."

"Tonight! Admit it, you've already invited him!"

Her father did not answer.

Wilhelmine sat down again and looked directly at him. "Who is it?"

"You don't know him. But I promise you, he's a good man. Handsome. With good manners. 38 years old. His name is Arnold Hofstädter. He's already made it to senior stud keeper in Trakehnen. And in case it's important to you: he wasn't married yet. He's been living in our inn for months, so I've been able to observe him very closely. He doesn't stare at the waitress and holds back on the brandy. And he always pays his rent and his bill accurately." Now it was out. Johann Mohn took a deep breath.

"You don't have to tell me what a good and honest man he is, everything has already been agreed for you, you've already arranged everything!"

Johann placed his hand on his daughter's pale fingers. "Child, we only want what's best for you."

Wilhelmine avoided his gaze and stood up again. "I'm going to the room now. Change my clothes. Because we're expecting a guest for dinner." She had wanted to say this somewhat cynically, but she was too weak to do so.

*

Wilhelmine stood in thelarge parlor infront of a mirror that showed her whole body and looked at herself. Her skin was fair, without the tanned patches around her neck and arms that ordinary women got from working in the sunlight. Her body was still firm and feminine with small but erect breasts. A few stretch marks were discreetly visible on her stomach. Her waist could be narrower, she thought. Her legs could also be longer. But her thighs were firm and her calves showed no blue veins. She sighed. Georg had liked and adored her so much, even though his sexual desire had plummeted after the birth of his progenitor. Or was it because of his penchant for alcohol? Should she even make herself pretty for an unknown man? She hesitated for a moment, but then a vague gut feeling won out. Why not?

She slipped into her linen underwear and squeezed into a corset that could be fastened at the front with hooks, because Svetlana was in Deeden and she didn't want to call a strange maid into her room. She also chose the long black dress with the discreet two dark green stripes that she had packed on an inner hunch. As far as the colors of her clothing were concerned, the mourning period of ten months offered few options. The dress had puffed sleeves and a modest neckline, covered by a rosette-shaped white flap. She tied her dark hair in a simple knot so that her precious earrings, which Georg had given her for Otto's birth, were clearly visible. She chose the wide belt with the large rectangular golden buckle to discreetly tame her slightly too large waist. She spritzed herself with a rose perfume from a bottle. She hadn't done that for a long time either. She put her wedding ring back on, hung a delicate amber necklace around her slender neck and applied some rouge. She turned back and forth in front of the mirror again. She was satisfied.

*

In the Stammtischstube, the table was set with the best china the Mohn family owned and silver cutlery. Crystal glasses for water and wine and earthenware mugs for beer were at the ready. Wilhelmine could see her parents' excitement about the upcoming dinner. Her mother was constantly tugging at the tablecloth and napkins. She had a similar hairstyle to her daughter and wore a brown flowered dress that hid her waist below the base of her large breasts and fell loosely over her round belly. Wilhelmine's father paced up and down the living room. When he tried to straighten a carafe of water on the table, he knocked over a glass. He kept reaching for his gray-striped suit jacket over his white stand-up collar shirt and velvet vest, as if he wanted to close it, but it wouldn't button up in front of his big belly. He stroked his little gray hair, which he had laid on his round skull with pomade from left to right. Again and again he plucked at his bushy moustache, rubbed his thick, always reddened nose and put his glasses with their thick lenses up and down.

"Johann, in God's name, why don't you sit down? You're making us all nervous," his wife demanded.

Johann continued to walk up and down the living room. Otto came in and marveled at the splendidly laid table and was delighted that he would be dining more festively today than he had for a long time. Wilhelmine entered and was greeted by her mother with a glass of wine. A sweet dessert wine, as she loved it. Her parents obviously left no stone unturned. They both toasted her in encouragement.

Then the guest arrived. His sonorous voice could already be heard through the open door as he asked the maid for directions. Immediately afterwards, he entered the parlor with an energetic stride. Arnold Hofstädter was indeed a handsome man. And much taller than Wilhelmine's husband had been.He fullfilled the Prussian guard standart, but also had a slight tendency to be portly. He wore a moustache that was slightly tapered on both sides, the so-calledKaiser Wilhelm. He also had a chin beard, which discreetly concealed his double chin. His hair was combed back tightly from a center parting with pomade. His eyebrows were bushy and rose slightly to the side, giving him a slightly diabolical expression. The narrow, deep-set eyes were covered by round glasses. The slender nose pointed, as far as the beard would allow, to a mouth framed by sensual lips. The fact that the stand-up collar of the white shirt could no longer be closed at the front was well concealed by an artfully knotted dark blue scarf. His broad shoulders were tucked into a dark gray, discreetly striped open jacket, under which an equally closed vest could be seen, the cuffs of which overhung his waist and from one button of which a golden watch chain with a gentle curve disappeared into his vest pocket. The dark striped trousers fell loosely onto shiny black lace-up shoes.

Judging by his name, he must have been one of the great-grandchildren of the Salzburg exiles who were welcomed to Königsberg by the Prussian King Frederick William I in 1733 with the slogan "Mir neue Söhne -euch ein mildes Vaterland". The exiles had been expelled from their Salzburg homeland because of their Protestant faith and settled in the East Prussian expanses, which had been depopulated after the plagues and wars of the 17th century.

Arnold Hofstädter stood in the doorway to the Stammtischstube, the setting of which he was fully aware of, first looked at the Mohn couple with an implied bow and then turned his gaze to Wilhelmine, who was blushing.

"Come in, Mr. Hofstädter. It is a great pleasure for us to welcome you as our guest," Johann Mohn greeted the head keeper of the Trakehnen estate.

Hofstädter took a step forward. "Thank you."

"Yes, come in," added Wilhelmina Mann. "May I introduce you to our daughter Wilhelmine?"

Arnold Hofstädter nodded. "The pleasure and honor is all mine." He took a step towards Wilhelmine and held out his hand to her. "Myheartfelt condolences, madam. I hope my presence is not inconvenient for you."

"Thank you very much, no. I'm grateful for a little distraction," Wilhelmine replied politely and took his hand, which he squeezed gently.

"Why don't we sit down?" Johann Mohn assigned his guest the chair next to his wife, opposite his daughter. He filled the delicate aperitif glasses with sweet wine and raised his own. "To a pleasant evening!"

Everyone sipped from their glasses. The maid came into the parlor and placed a large bowl of steaming vegetable soup on the table and filled everyone's plates. Johann folded his hands, looked around briefly and said: "Come, Lord Jesus, be our guest and bless what you have given us."

"Enjoy your meal," Wilhelmina Mohn wished and reached for her spoon. After the first cautious sip of the hot, hearty soup, she took the floor again. "Now tell us, dear Mr. Hofstädter, how you managed to get such a responsible post in Trakehnen at such a young age?"

Arnold put down his spoon, cleared his throat, looked first at the young Wilhelmine and then turned to the hostess.

"My father is the second chamberlain at Steinort Castle for Her Serene Highness Countess Anna von Lehndorf. The Countess discovered my interest in horses early on. I was even allowed to assist in the care of her riding horses. One fine day almost twenty years ago, when she came back from a ride, she asked me if I would be interested in going to Trakehnen. They were looking for talented young men like me there. You can imagine how happy I was."

"How interesting," said Wilhelmina. "And the Countess of Lehndorf suffered a similar fate to our poor Wilhelmine. She lost her husband at an early age and then continued to run Steinort Castle and the estate itself with great energy and prudence."

Hofstädter nodded. "She has very good people around her and appreciates that. Her son Carl Meinhardt, who is also known asCarolin his circles, has now taken over the estate. The young Count is a very introverted person. He doesn't really let anyone get close to him, they say."

"I hear he often has extravagant parties and has never given his heart to a woman," Wilhelmine's mother reported.

Arnold Hofstädter nodded. "I can't say anything more specific. But I have heard that he behaves very decently and fairly towards his people."

Johann noticed that his wife's curiosity was embarrassing his guest. "Please tell us about your famous Trakehnen stud farm. But first, please eat your soup before it gets cold."

Visibly relieved, Arnold Hofstätter reached for his spoon. When he had almost finished his plate, he outlined the eventful history of the stud farm during the Napoleonic years of the Prussian occupation and how it subsequently flourished again after it was placed under the control of the Ministry of Agriculture in 1848. He himself had been employed at the stud under State Stable Master Gustav Adolph von Dassel. He had initially taken the wrong path by crossing other horse breeds and then returned to breeding purebred Trakehners. The stud was now under the management of Count von Frankenberg and Proschlitz, but it was said that he was soon to be replaced.

"It is said that it will be Mr. Burchard von Oettingen. There were many reports about him in the newspapers about his study trips around the world in the field of horse breeding. He is said to have been a very good race rider as a young man."

Johann nodded: "I've read that too."

Arnold leaned back. The group had emptied their soup plates and, as if on cue, the maid appeared to clear away the empty dishes. Johann poured red wine for the ladies. "And you, dear Mr. Hofstädter, would you also like red wine or would you prefer a beer?"

"I'd love some red wine. Thank you."

"And our Otto gets goose wine," said Johann Mohn with a smile and poured some apple juice into a wine glass for his grandson. Otto loved horses and was fascinated by Hofstädter's story about the stud farm. His mother Wilhelmine had not said a word during the appetizer and had tried not to stare at the guest in an unseemly way, but could not escape a certain fascination.

The main course was served: Oven-baked duck with potatoes and bacon chanterelles. Otto got his beloved drumstick, the guest a whole leg, the women shared a breast and Johann took the second with wings. The cook had prepared a rich, deep brown sauce that went perfectly with the golden potatoes. The meal was so delicious that nobody spoke.

Johann then dabbed his mouth with his napkin, leaned back in his chair, full and satisfied, and turned back to his guest. "I'm sure your father gave you a lot of insight into the economic aspects of a farm?"

Arnold nodded and hurried to swallow so as not to speak with his mouth full. "My father introduced me to all the important tasks early on. He originally thought I would follow in his footsteps one day."

"Would it perhaps be possible for you to give our daughter a helping hand to get her farm going in March?"

Wilhelmine, startled, choked on the wine she had just drunk. "Father, please! Mr. Hofstädter has other things to worry about than looking after my farm!"

"My dear child, it was nothing more than a question," her father replied unperturbed and looked at Arnold Hofstädter in anticipation of an answer.

He smiled kindly and looked at Wilhelmine. "I'd be very happy to take a look at the records to see what seed sequences were planned for the coming season and what the seed and fertilizer stocks are! But only if it's really convenient for you."

Wilhelmine avoided the man's gaze and struggled for an answer. "I do not know. I have my people. They are good experienced people."

"So much the better. You'll already have your concept and I'd like to check it out. I agree with your father. There´s not much time left."

The maid came in, changed the dishes again and placed a plate of steaming potato pancakes and a large bowl of apple sauce in the middle of the table. She filled each of them up with as much as they wanted.

Otto got three buffers and a big mountain of mush and was happy.

Grandmother Wilhelmina then took him by the hand. "It's time for bed, young man. Say good night to everyone. I'll read you another story. From Struwwelpeter, you like it, don't you?"

Otto reluctantly obeyed.

Johann Mohn turned to the guest. "May I offer you a cigar? Or are you a pipe smoker?" he asked, reaching for a wooden box from the next table.

"I'd love a cigar."

"And you can't refuse a schnapps in honor, can you?"

"It is said to aid digestion."

Both took a black-brown cigar from the box and clipped the mouthpiece, also known as thehead, with an ornate golden cigar cutter. Johann held a thin cedar shaving in the flame of the table candle and handed the lit stick to the guest, who lit the cigar foot with a smacking sucking sound, which resulted in a strong cloud. Then he handed it to his host, who did the same. Enveloped in a thick cloud, Johann reached for the bottle of brandy and poured Arnold, his daughter and himself a drink.

"A fine drop from Königsberg. We have an exclusive contract with the distillery. Cheers."

"Cheers," Arnold replied.

While Wilhelmine sipped demurely, both men emptied their glasses in one go.

"To come back to your kind offer, Mr. Hofstädter. I would be happy to pick you up in Trakehnen on a day that suits you and accompany you to Deeden. It's on the way to my daughter's estate."

Before Wilhelmine could object, Arnold said: "Friday would suit me well. It would be a great pleasure for me to assist your gracious daughter."

Johann Mohn topped up his glass and raised it. "Wonderful! Thank you for your willingness to help."

He turned to his daughter. "We'll call on you next Friday, and you'll have Mr. Hofstädter look through the seed books and have an informative talk with the most important men in your people."

Wilhelmine knew that it was pointless to contradict her father. She also liked the idea of seeing Arnold Hofstädter again. It wasn't just resignation that she didn't contradict him now. Wilhelmina had rejoined them and after a schnapps, she and her daughter said their goodbyes, leaving the two men behind in intense conversation and thick cigar fog.

*

Wilhelmine sat upright in bed. The light of a pale, waning moon shone through the window, bathing the misty, snow-covered moorland in a ghostly light.

A handsome man, she thought. Does he just want to be an advisor or does he have more in mind? It's certainly what her parents want. She could imagine that too. But he could have any woman. Why was he single? Was he only married to his career? Would he even be interested in a farm like Wilhelmine's? And if so, how should Wilhelmine deal with her mourning period? Ten months was mandatory! To shorten things, after four months she could get a certificate from a midwife that she was not pregnant by her deceased husband.

She sighed. Why don't you just let it come to you? It had to go on somehow. Preferably with a strong man at her side. And he is a strong man.

She sank back into the pillows and decided it would be best to let everything come to her. Perhaps even with this handsome man by her side. Then she fell asleep.

*

It was after midnight when Arnold Hofstädter also retired to his room on the second floor. As he undressed and put on his cotton nightgown, he thought about Wilhelmine: Could more come of his consulting job? Her parents would probably like to see it. She is not a beauty, but she has a sympathetic nature. She is still of a fertile age. And she has the dowry of a handsome farm with 105 hectares to offer. His career at Trakehnen Stud, which had aroused the admiration of the landlords, was in reality not so successful. Although he had worked his way up over the past 19 years from riding lad to stud keeper and to senior stud keeper, his rise had stalled since then. Many a competitor had overtaken him on his way to becoming head of the stud, not only because he was younger, but also because he had the little word "von"in his name. What's more, two such upstarts from the lower nobility had each stolen a girlfriend from him. This had really shaken August's confidence in stable relationships.

Arnold breathed deeply. He was approaching forty. He needed a change in his life. And he had been offered this tonight. You're going to take this chance, he thought to himself and turned off the light.

*