Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Paraclete Press

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Serie: Paraclete Poetry

- Sprache: Englisch

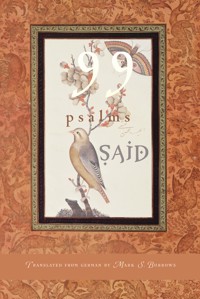

SAID's 99 Psalms are poems of praise and lament, of questioning and wondering. In the tradition of the Hebrew psalmist, they find their voice in exile, in this case one that is both existential and geographical. His decision to include 99 in this collection recalls the ancient Muslim tradition that ascribes 99 names to Allah, though the "lord"whom this psalmist addresses is not bounded by this or any other religious tradition. As psalms that turn to the "lord" with a lover's vulnerability, they avoid every trace of sentimentality. Rather, they seek to open us to the mystery of human life, warning us of the difficulties we face in our attempts to live peaceably together in the midst of our differences.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 76

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

99

psalms

TRANSLATED FROM THE GERMAN BYMARKS. BURROWS

2013 First Printing99 Psalms: SAID

Copyright © 2013 Preface, Afterword, and English translation by Mark S. Burrows

ISBN: 978-1-61261-294-2Originally published in Germany as SAID, Psalmen Copyright © 2007 Verlag C.H. Beck oHG, Munich.

Scripture quotations are taken from the New Revised Standard Version Bible, copyright © 1989 by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America, and are used by permission. All rights reserved.

The Paraclete Press name with logo (dove on cross) is registered trademark of Paraclete Press, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Said, 1947-

[Poems. Selections. English]

99 psalms / Said ; translated from the German with a preface and afterword by Mark S. Burrows.

pages cm

“Originally published in Germany as SAID, Psalmen (Munich: C. H. Beck, 2008)”—Title page verso.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-1-61261-294-2 (pbk.)

I. Burrows, Mark S., 1955- II. Title. III. Title: Ninety-nine psalms.

PT2679.A3355A2 2013

831'.92–dc23 2013007310

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, stored in an electronic retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other—except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Published by Paraclete PressBrewster, Massachusettswww.paracletepress.comPrinted in the United States of America

for my parents

Robert and Marion Burrows

with abiding gratitude

look

i attend to things

with their quietly flowing creed

SAID

Contents

Acknowledgments

Preface

Psalms

Notes on the Psalms

Afterword

Acknowledgments

Five of these poems first appeared in the translation issue of Poetry 199 (March 2012); four also appeared in Seminary Ridge Review 16 (Spring 2013).

Preface

The poems we need are often those that refuse to leave us unattended. They come to question and to comfort, to clarify and disturb, seeking in their own way to touch our lives and perhaps even to change us. They offer themselves as illuminations of a sort, casting their light into the shadows that cling to us and gesturing toward a path we might follow through the trials that beset us along the way.

Again and again, such poems startle us in our certainties as in our complacence. They remind us to look beyond what we know, or think we know, and, as the author of these psalms puts it, to “believe in truths / that expand beyond the field of our vision.” [11]1 They assure us when we stumble in our doubt that “only seekers see,” [73] inviting us to embrace the whole of our lives, including our disappointments and failings, as beginnings of a new path.”[L]et us touch the darkness and / the torn flesh of love,” [69] the poet suggests, finding our way to a form of prayer that is “like a river / between two shores,” seeking “new skin / that can bear this world.” [43] Poems of this sort activate what another poet has called “the acute intelligence of the imagination,” a transformative power representing “the sum of our faculties.” 2

These psalms engage us with such an imaginative intelligence. In their unique way they bear witness to the heart's descent into loneliness and despair, and gesture to the ascents we also know in moments of compassion and generosity. They speak words that unsettle our firmly held conventions, calling for “the strength to ponder and clarify” our lives. [53] They ask for what the poet calls “a wordless space close by” [52] so that we might make room in our lives for new ways of thinking and living. In such ways these late-modern psalms, like their ancient Hebrew antecedents, turn us with fierce honesty and authenticity toward the often difficult realities we face in our lives. They beckon us to come forth from the tombs of our grief, and rebuke us when we linger in the valleys of self-pity or resignation. Above all, they invite us to discover our own voice—and our own “self”—as we read them slowly, “chewing” their language to recall an image often found in ancient monastic literature, line by line, image by image, and even word by word. They open something within us, slowly and steadily, that can only be found in such a slow reading, leading to the insights and puzzlements we discover by means of “an incandescence of the intelligence,” one that “rescues all of us from what we have called absolute fact.” 3

When I first encountered these psalms in their original German, they seemed intimately familiar to me, though I'd not known of them before then. Nor had I ever met their author, the contemporary poet who goes by the pen name SAID, an Iranian who emigrated to Germany as an engineering student in the late 1960s—but eventually gave up these studies to pursue a writing career; I tell the story of my discovery of SAID's work in the Afterword to this volume.

When I first heard the poet reading several of these psalms, some of the lines ignited that rush of energy that comes in moments of unexpected insight, while others touched a deep sensibility within me through the intimate tenderness of their language. What drew me to them from the start was the power of their allurement, and their witness to truths we can only come to know in and through our embodied lives. In such ways they seemed remarkably like some of the Hebrew Psalms, though their thought-world is unmistakably modern, even late-modern, and thus often a distant echo of the cadences of their biblical predecessors.

Over the years since, the poems found in this strange and wonderful new psalter have become trusted companions on my journey. I hope they might become such a presence for you as well. If so, they will not come offering advice or promising answers to life's great questions. They will be more like the deep “stirrings” that unsettle us, that move us in the silent depths of our being, that “place” within us that is “boundary and center at once,” [28] as SAID puts it. But this will mean facing the anguish we know in our bodied lives and learning to “believe in the flesh / its extravagance and its incorrigibility.” [68] Such an experience is no small gift, even if often a discomforting one. Nor will it be unfamiliar to those who have heard the cry in our own lives that resounds in the ancient Psalter:

Deep calls to deepat the thunder of your cataracts;

all your waves and your billowshave gone over me. (Ps. 42:7)

Or, in the echo one hears in one of SAID's psalms:lordburnso that your light divides usbecause i seek refuge with youfrom my truths [77]

As you can see, these poems are distinctly—one might say peculiarly—modern in diction and voice. Yet if the function of psalms is to remind us of the complexities we face in our lives without offering answers, then SAID's psalms are not unconventional at all. Like the “wild wood dove” of Gerard Manley Hopkins's “Peace,” SAID's psalter “comes with work to do, he does not come to coo, / He comes to brood and sit.” This should be stated plainly at the outset as a kind of “consumer warning,” since many who turn to the biblical Psalms select the sweet and lovely ones and ignore or avoid the others—though these are probably the ones we need the most. Why? Because they insist on naming the often difficult story we encounter day by day in our lives, the one we face with all its duplicities in the shadows of our own hearts. A selective approach that would avoid such dark recesses, whether driven by fear or wishful thinking, is finally enervating because untrue—and thus unable to take account of the full range of our humanness.

A word of caution, then, at the outset: these new psalms have something of the sharp and rough edge felt in the rhetoric of the ancient Hebrew Psalter. They occasionally offer soothing words of comfort, but more often bring a measure of the prophet's stinging critique—aimed first of all at the psalmist's own “tribe.” None of these poems would ever be chosen to grace a modern greeting card, the kind featuring soft pastel backgrounds, luxurious floral bouquets, or idyllic sunsets over quiet harbors. No, these are psalms for a deeper and more rugged journey, one that faces the deceptions and despairs of our hearts and exposes the hypocrisy choking our public life. For this reason, they are the psalms we most need today, warning us against the dangers of “the songs of our solemn assemblies,” in the thundering words of the prophet Amos, as well as the banalities of misguided piety.