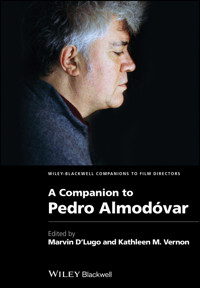

A Companion to Pedro Almodóvar E-Book

155,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: WBCF - Wiley-Blackwell Companions to Film Directors

- Sprache: Englisch

A Companion to Pedro Almodóvar

“Marvin D’Lugo and Kathleen M. Vernon give us the ideal companion to Pedro Almodóvar’s films. Established and emerging writers offer a rainbow of insights for fans as well as academics.”

Jerry W. Carlson, Professor of Film Studies, The City College & Graduate Center CUNY

“Rarely has a contemporary film artist been treated to the kind of broad, rich discussion of their work that can be found in A Companion to Pedro Almodóvar.”

Richard Peña, Professor of Film Studies, Columbia University

Once the enfant terrible of Spain’s youth culture explosion, the Movida, Pedro Almodóvar’s distinctive film style and career longevity have made him one of the most successful and internationally known filmmakers of his generation. Offering a state-of-the-art appraisal of Almodóvar’s cinema, this original collection is a searching analysis of his technique and cultural significance that includes work by leading authorities on Almodóvar as well as talented young scholars. Crucially included here are contributions by film historians from Almodóvar’s native Spain, where he has been undervalued by the academic and critical establishment.

With a balance between textual and contextual approaches, the book expands the scope of previous work on the director to explore his fruitful collaborations with fellow professionals in the areas of art design, fashion, and music as well as the growing reach of a global Almodóvar brand beyond Europe and the United States to Latin America and Asia. It also proposes a reevaluation of the political meanings and engagement of his cinema from the perspective of the profound cultural and historical upheavals that have transformed Spain since the 1970s.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 1283

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

Contents

Notes on Contributors

Acknowledgments

Introduction: The Skin He Lives In

A Spotlight on the Self-Conscious Auteur

The Companion to Pedro Almodóvar

PART I: Bio-Filmography

1 Almodóvar’s Self-Fashioning

2 Creative Beginnings in Almodóvar’s Work

Searching for His Own Voice

The Short Stories in Relatos

Epilogue

3 Almodóvar and Hitchcock

Introduction: Self-Education via Hitchcock

Almodóvar’s Guilt Complex from Spellbound to Laberinto de pasiones

Casting and Close-ups in Entre tinieblas and Stage Fright

The Domestic Crime Scene Enlivened by Wallpaper: “Lamb to the Slaughter” and ¿Qué he hecho yo para merecer esto!

Looking through Objects and Almodóvar’s “MacGuffin”: From Dial M for Murder, The 39 Steps, Strangers on a Train, and Rear Window to Mujeres al borde de un ataque de nervios

Conclusions

4 A Life, Imagined and Otherwise

Inventing the Self: Autobiography between Fact and Fantasy

A Portrait of the Young Gay Man as a Star-to-be: Personal Experience into Cultural Mythologies

PART II: Spanish Contexts

5 El Deseo’s “Itinerary”

Marks of Identity

Family Resemblance

The Back Story: Almodóvar

The Course of Things: El Deseo’s Other Films

Other Stories: Latin American Co-productions

Home Cinema

Conclusions

Acknowledgments

6 Almodóvar and Spanish Patterns of Film Reception

La ley del deseo

Kika

Hable con ella

Conclusions

7 Memory, Politics, and the Post-Transition in Almodóvar’s Cinema

From Novela Rosa to Film Noir: The Breakdown of the Transitional Paradigm

Carne trémula: The Irruption of History

Memory and the Redemption of Theater in Todo sobre mi madre

Reinterpreting the Past: La mala educación

Conclusions

8 The Ethics of Oblivion

Visual Palimpsests and Narrative Arrhythmias

Rhopography: Making the Apparently Trivial into a Movie Star

The Ethics of Makeup

PART III: At the Limits of Gender

9 Our Rapists, Ourselves

Specularizing Visions of Excess: Of Human Bondage, Petits Mortes, Parts Maudites, and Rape

Masters of Delusion

Immaterial Girls: Of Graves and Private Places

10 Paternity and Pathogens

11 Domesticating Violence in the Films of Pedro Almodóvar

12 La piel que habito

Acknowledgments

PART IV: Re-readings

13 Re-envoicements and Reverberations in Almodóvar’s Macro-Melodrama

Mastering Sound: Re-envoicing the Movida and Macro-Melodrama

Musical Substitutions and Intertexts in Laberinto de pasiones

Dubbing as Re-envoicement in Mujeres al borde de un ataque de nervios

The Maternal Voice in La flor de mi secreto

Macro-Melodrama in Hable con ella and Todo sobre mi madre

Retro-seriality in Los abrazos rotos: Reverberations in the Age of Audio Culture

14 The Flower of His Secret

Acknowledgments

15 Scratching the Past on the Surface of the Skin

Introduction

Torn Surfaces, Shattered Subjectivities

The Skin of the Dress

Cinema as an Embodied Witnessing Practice

Conclusion

16 Almodóvar’s Stolen Images

Cinematic Quotation as Theft

Visual Metaphors as Poaching

Plagiarism, Pastiche, and “Transvestism”

The Search for Style

Textual Transvestism

PART V: Global Almodóvar

17 Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown

18 Almodóvar’s Global Musical Marketplace

All About World Music

Caetano Veloso: Hearts, Minds, and Market Share

Chavela Vargas: Icon and Muse

Buika: Synthesis and Synergies

Conclusions

19 Almodóvar and Latin America

Mapping Cultural Affinities

Tango and Communal Memory

Constructing a New Geocultural Imaginary

An Auditory Imaginary

Co-Producing a Cinematic Latin America

20 Is there a French Almodóvar?

Distribution and Reception of Almodóvar’s Films in France

From the Untranslatable to the Genuine

Towards Translatability: The Global

Just Another filmmaker (or almost)

21 Almodóvar in Asia

Conclusion

PART VI: Art and Commerce

22 To the Health of the Author

Color

Set Design

Atrezzo

Meta-narrative

Hospitals

Conclusion

23 Making Spain Fashionable

A History of Spanish Fashion and State Policy

Almodóvar and Costume Design in Film

Made in Spain

Made in Europe

La flor de mi secreto

Conclusion

24 Almodóvar, Cyberfandom, and Participatory Culture

Internet Users, Piracy, and the Re-regulation of the Web

The “Sinde Law”: from de la Iglesia to Almodóvar

From La Edad de Oro to Enrique Goded: The Auteur–Fan Interface

“Almodóvar” as El Deseo S.A., Fan-made Artifacts and the Question of Ownership

From “Almodovarlandia” to Facebook: Social Networking and the Demise of the Cinephilic Object?

Conclusion: Almodóvar and the Future of Participatory Culture

Acknowledgments

Index

Eula

Wiley-Blackwell Companions to Film Directors

The Wiley-Blackwell Companions to Film Directors survey key directors whose work constitutes what is referred to as the Hollywood and world cinema canons. Whether Haneke or Hitchcock, Bigelow or Bergmann, Capra or the Coen Brothers, each volume, composed of twenty-five or more newly commissioned essays written by leading experts, explores a canonical, contemporary, and/or controversial auteur in a sophisticated, authoritative, and multidimensional capacity. Individual volumes interrogate any number of subjects – the director’s oeuvre; dominant themes, well-known, worthy, and underrated films; stars, collaborators, and key influences; reception, reputation, and above all, the director’s intellectual currency in the scholarly world.

Published

This edition first published 2013© 2013 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Blackwell Publishing was acquired by John Wiley & Sons in February 2007. Blackwell’s publishing program has been merged with Wiley’s global Scientific, Technical, and Medical business to form Wiley-Blackwell.

Registered OfficeJohn Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK

Editorial Offices350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UKThe Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK

For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services, and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley-blackwell.

The right of Marvin D’Lugo and Kathleen M. Vernon to be identified as the authors of the editorial material in this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books.

Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book. This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold on the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A companion to Pedro Almodóvar / edited by Marvin D’Lugo and Kathleen M. Vernon. p. cm. – (Wiley-Blackwell companions to film directors) Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4051-9582-9 (hardback : alk. paper) 1. Almodóvar, Pedro–Criticism and interpretation. I. D’Lugo, Marvin. II. Vernon, Kathleen M., 1951– PN1998.3.A46C585 2013 791.4302′33092–dc23

2012033137

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Cover image: Pedro Almodóvar © AF archive / AlamyCover design by Nicki Averill Design and Illustration

Notes on Contributors

Dean Allbritton is an Assistant Professor of Spanish at Colby College with a Ph.D. in Hispanic Languages and Literature from SUNY Stony Brook. His work analyzes metaphors of illness and masculinity in contemporary Spanish film as focal points for larger discourses of national and societal health. His critical interests include the fields of illness and disability studies, film theory, contemporary Spanish film, and masculinity studies. He has published articles in Studies in Hispanic Cinemas and Post Script.Isolina Ballesteros is Associate Professor at the Department of Modern Languages and Comparative Literature of Baruch College, CUNY. Her teaching focuses on modern peninsular studies (nineteenth- and twentieth-century literature and film), comparative literature, and Spanish and European film. Her field of specialty is contemporary Spanish cultural studies and her current research reflects a dual interest in gender, ethnicity and migration to Europe, and the cultural memory of the Spanish Civil War. She is the author of two books: Escritura femenina y discurso autobiográfico en la nueva novela española (1994) and Cine (Ins)urgente: textos fílmicos y contextos culturales de la España postfranquista (2001). She is currently working on a book called: “Undesirable” Otherness and “Immigration Cinema” in the European Union.Josetxo Cerdán Los Arcos is Associate Professor in the Department of Communication, Journalism and Advertising Studies at the Universitat Rovira i Virgili where he was coordinator of the M.A. degree program from 1998 to 2008. He is Artistic Director of Punto de Vista, the Festival Internacional de Cine Documental de Navarra. He is author of Ricardo Urgoiti. Los trabajos y los días (2007) and editor of the books Mirada, memoria y fascinación (2001); Documental y Vanguardia (2005); Al otro lado de la ficción (2007); and Suevia Films – Cesáreo González (2005); Signal Fires: The Cinema of Jem Cohen (2010). His principal research areas are non-fiction film, Spanish cinema, and television.Gerard Dapena is a scholar of Hispanic cinemas and visual culture. He received his Ph.D. in Art History at The Graduate Center, CUNY. His dissertation examined the interface of film and painting in post-Civil War Spanish cinema. He has published and lectured on different aspects of Spanish and Latin American film and art history and taught at New York University, Bard College, Macalester College, The New School, and The School of Visual Arts, among other institutions. Currently, he is working on a book-length study of early Francoist cinema.Celestino Deleyto is Professor of Film and English Studies at the University of Zaragoza, Spain. He is the author of The Secret Life of Romantic Comedy (2009) and co-author, with María del Mar Azcona, of Alejandro González Iñárritu (2010).Marina Díaz López holds a doctorate in film history from the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid. She is in charge of the film and audiovisual office of the Instituto Cervantes (Madrid). She had edited two collections of essays in Latin American cinema in collaboration with Alberto Elena: Tierra en trance. El cine latioamericano en 100 películas (1999) and The Cinema of Latin America (2000) and is the author of various articles on the transnational dimensions of Mexican and Spanish cinemas. She was part of the editorial board of the Spanish film journals Secuencias and Revista de Historia del cine and currently serves on the board of Studies in Hispanic Cinemas.Marvin D’Lugo is Professor of Spanish and Comparative Literature and Adjunct Professor of Screen Studies at Clark University where he teaches courses on Spanish, Latin American and U.S. Latino cinemas. He is author of The Films of Carlos Saura: The Practice of Seeing (1991); Guide to the Cinema of Spain (1997); and Pedro Almodóvar (2006). He has also written extensively on Cuban, Mexican, and Argentine cinemas. He is currently working on a book on Pedro Almodóvar in Latin America. Since 2008 he has served as Principal Editor of Studies in Hispanic Cinemas. He is a member of the editorial boards of Archivos de la Filmoteca (Filmoteca Valenciana), Secuencias (Universidad Autónoma de Madrid), and Transnational Cinemas.Miguel Fernández Labayen is Assistant Professor at the Universidad Carlos III de Madrid. He has written several articles on experimental filmmaking and contemporary Spanish cinema, contributing to collective books such as Latsploitation, Exploitation Cinemas, and Latin America (2009) and Contemporary Spanish Cinema and Genre (2009). He is the co-director of “Xperimenta: Contemporary Glances at Experimental Cinema,” an event held at the Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona (CCCB). His current research explores contemporary Spanish audiovisual culture.Julián Daniel Gutiérrez-Albilla is Assistant Professor of Spanish and Comparative Literature at the University of Southern California. His publications on Spanish and Latin American cinema have appeared in the Bulletin of Hispanic Studies, Spain on Screen: Developments in Contemporary Spanish Cinema, Bulletin of Latin American Research, Hispanic Research Journal, Visual Synergies in Fiction and Documentary Film from Latin America, Journal of Romance Studies, Gender and Spanish Cinema, and Studies in Hispanic Cinemas. His book, Queering Buñuel: Sexual Dissidence and Psychoanalysis in his Mexican and Spanish Cinema, was published in 2008. He has forthcoming publications in a Blackwell Companion to Spanish Cinema, in an edited volume on Hispanic and Lusophone Female Filmmakers and in the Revista de Crítica Literaria Latinoamericana. He is currently working on a book about ethics, memory, and subjectivity in contemporary Spanish cinema.Javier Herrera is Librarian of the Filmoteca Española and Curator of Luis Buñuel’s personal archives. He is author of Picasso, Madrid y el 98 (1997), Las Hurdes un documental de Luis Buñuel (1999), El cine en su historia (2005), El cine. Guía para su estudio (2005), and Estudios sobre Las Hurdes de Buñuel (2006). Besides his contributions to various special journal issues devoted to Buñuel, he has also edited critical collections on film topics: La poesía del cine y Los poetas del cine (2003); El documental latinoamericano (2004); and with Cristina Martinez-Carazo he co-edited Hispanismo y cine (2007) and a special issue of Letras Peninsulares devoted to Buñuel y/o Almodóvar. El laberinto del deseo (2010).Juan Carlos Ibáñez is Associate Professor of Audiovisual Communication at the Universidad Carlos III de Madrid. His work centers on the analysis of the history of cinema and television in the context of the social, cultural, and political transformations taking place in contemporary Spain. During the last few years he has focused on the relation between the European economic crisis and national identity in Spanish audiovisual culture. His recent publications include the co-edited volume, Memoria histórica e identidad en cine y televisión (2010) and an article on the introduction of postmodern thought and aesthetics in Spain, “Comedia sentimental y posmodernidad en el cine español de la transición a la democracia” (2012).Dona Kercher is Professor of Spanish and Film at Assumption College in Worcester, MA. She has published numerous articles on Spanish Golden Age literature and Spanish film, especially focusing on Manuel Gutiérrez Aragón and Álex de la Iglesia. This essay is part of her forthcoming book Latin Hitchcock.Marsha Kinder began her career as a scholar of eighteenth-century English literature before moving to the study of transmedial relations among various art forms. She currently is Professor of Critical Studies in the University of Southern California School of Cinematic Arts where she has been teaching since 1980, and where her specialties include Spanish cinema, narrative theory, database documentaries, and digital culture. She has published over 100 essays and ten books, including Blood Cinema: The Reconstruction of National Identity in Spain (1993), Refiguring Spain (1997), Playing with Power in Movies, Television and Video Games (1993), and Kids’ Media Culture (2000). Her current book in progress is The Discreet Charms of Database Narrative. She has been a member of the editorial board of Film Quarterly since 1977. In 1995 she received the USC Associates Award for Creativity in Scholarship and in 2001, was named a University Professor for her innovative transdisciplinary research. Since 1997 she has directed “The Labyrinth Project,” a research initiative on interactive narrative, producing database documentaries and new models of digital scholarship in collaboration with artists, scholars, scientists, and archivists. These works have been featured at museums, film and new media festivals, and conferences worldwide and have won prestigious awards, including the New Media Invision Award, the British Academy Award, and the Jury Award at Sundance for New Narrative Forms.Leora Lev is Professor of Foreign Languages at Bridgewater State University and Lecturer in the ISA Paris Fine Arts Program. She edited and contributed with essays and a John Waters interview to Enter at Your Own Risk: The Dangerous Art of Dennis Cooper (2006), and has published chapters, essays, and reviews in Film Quarterly, the Journal of the History of Sexuality, the South Atlantic Review, Revista de Estudios Hispánicos, Anales de Literatura Española Contemporánea, the Catalan Review, American Book Review, Post-Franco, Postmodern: The Films of Pedro Almodóvar (1995), Spanish Writers on Gay and Lesbian Themes: A Bio-Critical Sourcebook (1998), The Encyclopedia of Sex and Gender (2007), Dennis Cooper: Writing at the Edge (2007), and the text for Paris-based artist Scott Treleaven’s exhibit (Kavi Gupta Gallery, Chicago/Berlin). She was interviewed by the New York Times, the Village Voice, and New York University Research on the topic of transgressive art.Alberto Mira is Reader in Film Studies at Oxford Brookes University (U.K.), where he teaches courses on Spanish cinema, classical Hollywood narration and stars. He co-devised the Film Studies undergraduate program in 2004, and also contributes to the postgraduate M.A. in Popular Cinema. Between 1997–99, he was Queen Sofía Research Fellow at Exeter College, Oxford. He has published extensively on Francoist cinema, gender in Spanish cinema, Iván Zulueta, and Pedro Almodóvar for various Spanish, British, and U.S. journals and essay collections. He was editor of 24 Frames: The Cinema of Spain and Portugal (2005). As one of the leading specialists in Spanish gay history and culture, he is the author of the dictionary Para entendernos (1999) and the cultural history De Sodoma a Chueca (2004) as well as a monograph on gay and lesbian cinema: Miradas Insumisas. Gays y lesbianas en el cine (2008). Other publications include articles on Lorca, Latin American literature and monographs on Spanish theater, as well as critical editions and Spanish translations of plays by Oscar Wilde and Edward Albee. He is the author of two novels, Londres para corazones despistados (2004) and Como la tentación (2005).Adrián Pérez Melgosa is Assistant Professor in the Department of Hispanic Languages and Literature at SUNY Stony Brook. His work centers on transnational and cross-cultural representation and politics in both the Americas and Spain. He has published articles in Social Text, Journal of Spanish Cultural Studies, Studies in Hispanic Cinemas, and Latin American Literary Review, among other journals. The volume, Revisiting Jewish Spain, which he co-edited with Tabea Linhard and Daniela Flesler, appeared as a special issue of the Journal of Spanish Cultural Studies (Summer 2011). His most recent book is Cinema and Inter-American Relations: Tracking Transnational Affect (2012).Vicente Rodríguez Ortega is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Journalism and Communications at the Universidad Carlos III de Madrid. He is the co-editor of Contemporary Spanish Cinema and Genre (2009) and has published essays in a variety of book collections and journals such as Transnational Cinemas, Studies in European Cinema, Film International and Icono 14. He is the author of the forthcoming volume La Ciudad Global en el Cine Contemporáneo: una perspectiva transnacional. He is also a regular contributor to the online film journal Reverse Shot and has made a feature-length documentary titled Freddy’s.Noelia Saenz holds a Ph.D. in Critical Studies from the University of Southern California. Her work explores issues of gender, sexuality, gendered violence and identity in contemporary Spanish, Latin American and Latino cinema.John D. Sanderson is Senior Lecturer in the Department of English Studies of the Universidad de Alicante, Spain, where he teaches film and literature, and film and theater translation. He is also a lecturer in postgraduate courses at the Universities of Málaga, Valencia, and the Centro de Estudios Ciudad de la Luz (Alicante). He is the author of the book Traducir el teatro de Shakespeare: figuras retóricas iterativas en Ricardo III (2002), and the editor of several volumes including ¿Cine de autor? Revisión del concepto de autoría cinematográfica (2005), Trazos de cine español (2007) and Constructores de ilusiones: la dirección artística cinematográfica en España (2010), the last with Jorge Gorostiza. He is currently writing a book called La trayectoria cinematográfica internacional de Francisco Rabal.Jean-Claude Seguin is Agrégé de l’université and since 1996 Professor at the University of Lyon. His research focuses on the history of Spanish cinema and the origins of cinema internationally. He is president of GRIMH (Grupo de Reflexión sobre la Imagen en el Mundo Hispánico) which organizes a conference every two years. He has given invited lectures in universities and at conferences in France, Spain, Belgium, Germany, Great Britain, and Mexico. He is the author of over 100 articles and fifteen books, including Histoire du cinéma espagnol (1994), La Production Cinématographique des Frères Lumiére (1996), Los orígenes del cine en Cataluña (2004), Pedro Almodóvar o la deriva de los cuerpos (2009), and La llegada del cine de España.Paul Julian Smith is Distinguished Professor in the Ph.D. Program in Hispanic and Luso-Brazilian Languages and Literatures at The Graduate Center, CUNY, and was for twenty years Professor of Spanish at Cambridge University. He is the author of fifteen books including Desire Unlimited: The Cinema of Pedro Almodóvar (1994, 2000), Amores Perros (2008), and Television in Spain (2006). He has been Visiting Professor in ten universities including Stanford, Berkeley, and the Universidad Carlos III de Madrid. He has published over seventy academic articles in learned journals and collections and has received over 100 invitations to speak at international conferences or to give invited lectures around the world. He is a regular contributor to Sight & Sound, the magazine of the British Film Institute, and a columnist for Film Quarterly, published by the University of California. He was a Juror for the Mexican Feature Competition in the International Film Festival of Morelia, Mexico, 2009 and Cinema Tropical’s Latin American Film Competition, 2011. He was elected Fellow of the British Academy in 2008.E. K. Tan is Assistant Professor of Comparative Literature and Cultural Studies in the Department of Cultural Analysis and Theory at SUNY Stony Brook. His areas of interest include Sinophone literature and film, modern and contemporary Chinese literature, Southeast Asian studies, Asian Diaspora studies, cultural translation, globalization, transnationalism, and film theory. He is completing a book manuscript tentatively entitled Translational Identity: Articulations of Chineseness in the Literary Imaginaries of the Nanyang Chinese.Kathleen M. Vernon is Associate Professor and Chair of the Department of Hispanic Languages and Literature at the SUNY Stony Brook where she teaches courses on Spanish and Latin American cinema and culture. She has published widely on various aspects of Spanish cinema from the 1930s to the present, with special focus on musical and historical film, melodrama and stardom, documentary, and women’s cinema. She is co-editor of the first English-language journal devoted to Spanish and Latin American film, Studies in Hispanic Cinemas. Her publications include The Spanish Civil War and the Visual Arts (1990) and Post-Franco, Postmodern: The Films of Pedro Almodóvar (1995). She is currently completing a monograph entitled The Rhythms of History, Cinema, Music and Cultural Memory in Contemporary Spain and two multi-authored books, The Mediation of Everyday Life: An Oral History of Cinema-Going in 1940s and 50s Spain and Film Magazines, Fashion and Photography in 1940s and 50s Spain.Francisco A. Zurian is Director of the Permanent Inter-University Research Seminar “Gender, Aesthetics and Audiovisual Culture” of the FONTA Research Group, Department of Audiovisual Communication and Publicity-1, at the Universidad Complutense de Madrid (UCM). His research focuses on aesthetics and theory of film and audiovisual media; cultural and gender studies applied to audiovisual culture; audiovisual narrative and script; and film, television and contemporary Spanish culture, with a special interest in the cinema of Pedro Almodóvar. His publications include the books, Pensar el cine (2011) and Manual de Iniciación al Arte Cinematográfico (1996), as author, and Género, sexualidad y estética en la cine y la televisión: cuestiones de representación (2012) and Pedro Almodóvar, El cine como pasión (2005), as editor, as well as numerous book chapters and articles.

Acknowledgments

A volume such as this, by its very nature, is a transnational venture, the product of intense collaboration among scholars and members of the Spanish film industry engaged in a cross-cultural dialogue that reflects the multiple dimensions of critical thought that surround Pedro Almodóvar’s cinema in Spain, France, the United Kingdom and the United States. We are especially indebted to Jayne Fargnoli, our editor at Wiley-Blackwell who first encouraged us to develop our conception of this Companion to Pedro Amodóvar’s cinema and who has served as a constant source of support and sage advice during all phases of the preparation of this volume.

Special thanks must also go to Agustín Almodóvar and Diego Pajuelo Almodóvar who gave unstintingly of their time in response to all our queries and who heightened our understanding of Almodóvar’s cinema in the contexts of the Spanish film industry and global movie culture. They provided us with access to El Deseo’s archival resources on the national and international reception of Almodóvar’s films. Our thanks also go to Lola García who helped us navigate through the vast archives of El Deseo as we put together the visual backdrop to this volume. She was joined by a team of equally resourceful and energetic members of El Deseo’s family: Bárbara Peiró, Mercedes González Barreira, and Anna Bogutskaya.

We were fortunate to have been able to call upon the expertise of our friends in Madrid, Margarita Lobo of the Filmoteca Española, who provided advice and direction on issues of historical contexts of post-Franco film culture, and to Fran Zurian who offered us the insights of his own experience of putting together an earlier important anthology on Almodóvar.

One of the unique challenges of editing an anthology of this sort is the need to coordinate a team of scholars who come from a diverse range of cultural and critical traditions. Each has demonstrated a passionate engagement in their own work on Almodóvar. Thus, a key part of our task has been to encourage creativity and originality but to try to balance the intensity of individual insights with the volume’s goal of a collective coherence on the subject of Almodóvar’s cinema. This has involved a unique kind of collaborative effort in which contributors have often been called on to rethink and at times reorder their own contributions in ways that promote the overall design of the volume. We have been fortunate in working with a team of first-rate scholars whose groundbreaking approaches to Almodóvar’s cinema are only matched by their intellectual generosity and willingness to collaborate in the formation of a collective discourse that is greater than the sum of the individual parts. This volume benefited tremendously from their uncommon scholarly esprit de corps.

On the technical level, our efforts have been supported by the thoroughly professional production team at Wiley that included Julia Kirk and Tessa Hanford.

Finally, our most heart-felt gratitude must go to Carol D’Lugo and Cliff Eisen, who served as sounding boards for our ideas and editors-at-large, providing loving support through the inevitable frustrations that always accompany a project of this nature.

Introduction

The Skin He Lives In

Marvin D’Lugo and Kathleen M. Vernon

A Spotlight on the Self-Conscious Auteur

Since the moment of his on-screen appearance as the master of ceremonies at the “General Erections” contest in his first commercially released film, Pepi, Luci, Bom y otras chicas del montón/Pepi, Luci, Bom and Other Girls Like Mom (1980), Pedro Almodóvar has never shied away from the self-referential spotlight, both in and around his movies. Over the years, the in-your-face Almodóvar has moved out of the sights of the camera lens—his last on-screen appearance in one of his own films was in La ley del deseo/Law of Desire (1987)—even as his off-screen promotion of his films has increased. By May 2011, with the Cannes Film Festival premiere of his eighteenth feature, La piel que habito/The Skin I Live In, we find on display the essential paradox of “auteur desire,” as Dana Polan called it (2001: n. p.), that mutual construction by filmmaker and spectator or critic of an authorial persona embodied and expressed through an artistically recognized body of work. On the surface, as he would claim to Spanish interviewer Angel Harguindey (2011), the film is not about him, yet it was presented and received through a festival promotion that makes the suggestion of La piel as an allegory of his own authorship unavoidable. That self-referentiality begins in the choice of a title for the film based on the novel Tarantula (Thierry Jonquet, 2005). Once before, in ¿Qué he hecho yo para merecer esto!/What Have I Done to Deserve This? (1984), he teasingly invited those interpretations by choosing the first-person pronoun in the film’s title. In that case, the narrative agency of the “I” of the title hinted at a symbolic identification between Almodóvar’s heroine, Gloria, brilliantly played by Carmen Maura, and the filmmaker’s own artistic and social biography.1

La piel ’s title similarly draws our attention to the agent of action, but with a notable ambiguity since none of the surface references suggest any overt biographical connection between the mad scientist, Robert Ledgard (Antonio Banderas), and Almodóvar’s own life or career. The film’s plot follows Ledgard, a famous plastic surgeon, who kidnaps the young man Vicente (Jan Cornet) who attempted to rape his daughter and in doing so aggravated her mental breakdown, eventually leading to her suicide. Ledgard holds the young man captive in his fortress home, performing a radical form of cosmetic surgery, including a vaginoplasty, that transforms Vicente into Vera (played by Elena Anaya) with the face of his deceased wife. In a twist on the dual Frankenstein–Pygmalion plot, Ledgard falls in love with his creation who appears to go along with his/her captor only to murder him at the end. One might therefore reasonably assume that the “I” of the film’s title more appropriately refers to the regendered Vicente/Vera than to the creator/victimizer Ledgard. It is on this level of opaque associations, far removed from the film’s explicit narrative, that authorial self-reference begins to take shape.

Ledgard’s determination is to develop a superior form of human skin, impervious to fire or puncture wounds, as well as the effects of ageing. This emphasis on skin as the focus of the mad doctor’s experimentation, reflected in the formulation of the film’s title, suggestively moves us to connect his efforts to the magical properties of that other skin, celluloid, which in classical cinematic terms captures the image in time and does not age. Almodóvar’s film, in fact, is very much about ageing as well as about the self-conscious construction of identity that the skin surgeon, like the filmmaker, proffers. Aside from Almodóvar’s obvious lifting of major plot elements from Georges Franju’s classic horror film, Les yeux sans visage/Eyes without a Face (1960), La piel contains very few of the cinematic quotes from other directors or films of the type that usually abound in Almodóvar’s cinema. Instead, the film’s title, alluding most obviously to the double perspective of a man imprisoned in the body of a woman, suggests a subtler and more complex allegorical cinematic signifier rooted in the curious etymology of the Spanish word for film, “película,” which derives from the same Latin root as the word for skin (“piel” in Spanish).2 Out of such surface wordplay, first postulated in Almodóvar’s title, we may discern that much of what surrounds La piel as the latest installment of an ongoing discourse on film authorship alludes to the cinematic allegories of lives lived and those captured through technologies related to representation and appearance.

These embedded authorial self-references are only heightened by the decision to stage the world premiere of the film at the 2011 Cannes Film Festival. Beyond its standing as a prestigious international launch site, Cannes offers the occasion for the biographical auteur and his film to share the spotlight. The French festival has long held a special personal association for Almodóvar. He had brought his early film, Laberinto de pasiones/Labyrinth of Passion to Cannes in 1982 but the film was ignored and, as he recalled, he felt like a tourist (Limnander 2009: 64). He would return again “officially” on at least six more occasions to participate in increasingly visible roles in the ceremonial competition. After serving as a member of the festival jury in 1992, he later won the Best Director award for Todo sobre mi madre/All About My Mother (1999). La mala educación/Bad Education opened the festival in 2004 and he won the award for Best Screenplay for Volver in 2006, with the film’s female leads capturing a collective award for Best Actress. His fifth official appearance at the festival was to compete with Los abrazos rotos/Broken Embraces in 2009. As in his previous visits, the festival’s main prize, the coveted Palme d’Or, eluded him, as it would again in 2011.

There is also an underlying artistic narrative linking Almodóvar with Cannes. Together with the non-competitive New York Film Festival, Cannes has played a crucial role in constructing the image of the international Almodóvar. Not coincidentally, it was the festival that frequently provided the stage for another legendary Spanish filmmaker, Luis Buñuel. Over the last three decades, Almodóvar has come to be viewed generally as the heir to Buñuel. So sure were the organizers that La piel would be an occasion of note, that they scheduled the film’s screening to coincide with the fiftieth anniversary of the original, and highly consequential, screening of Viridiana.3 At first glance, such extravagant extra-cinematic details might seem to say less about the film than its commercial exploitation. Yet, as David James reminds us in Allegories of Cinema (1989), a film never exists in a purely textual vacuum but as the product and projection of the complex and layered operation that is the institution of cinema itself: “Cinema is never just the occasion of an object or a text, never simply the location of a message or an aesthetic event.. . . [but t] he whole panoply of visual and aural media, of advertising, of journalism, of the political process and the urban landscape of signs. . . . A film’s images and sounds never fail to tell the story of how and why they were produced—the story of their mode of production” (1989: 5).

This series of contexts beyond the object of cinema—its multiple processes of creation, circulation, and construction of modes of reception—all tied to the persona of Almodóvar the auteur guides the elaboration of the present volume. Like the self-referential allegory of cinema that is contained in microcosm in every aspect of Almodóvar’s brand of filmmaking, the Cannes premiere of La piel provides an opportunity to shed light on the salient features of the filmmaker’s trajectory in a career that now spans thirty years.

At Cannes, Almodóvar would briefly share the spotlight with another cinematic personality, Antonio Banderas, an actor whose career, some would say, was invented by Almodóvar when the former made his first appearance in Laberinto de pasiones. Still it was Banderas’s notorious role in La ley del deseo that brought the young actor to international attention, eventually leading to his crossover career in Hollywood. With major and secondary roles in five of Almodóvar’s first eight films, Banderas last appeared in an Almodóvar film some twenty-one years earlier in ¡Átame!/Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down! (1990). The actor’s return to his cinema “home” with La piel led many spectators and critics to note the thematic similarities between the two films in their different takes on a kidnapping narrative.

Much had transpired in the two decades since the two men last worked together. Banderas has become a familiar face and an even more familiar voice for American audiences. Almodóvar, whose star was already in the ascendancy following his 1988 crossover hit, Mujeres al borde de un ataque de nervios/Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown, in which Banderas had a supporting role, has achieved an artistic standing that places him among the very few auteurs—Hitchcock, Buñuel, Chaplin—who might be classified as matrix figures whose impact transcends the purely textual domain of cinema. In other words, following Michel Foucault’s famous meditation on authorship, Almodóvar not only possesses the stylistic consistency that characterizes authorship, but he is also an “initiator of discursive practices” (1977: 131). That is, he has established a cinematic style that other filmmakers imitate (the adjective “Almodovarian” is not only applied to his own work but also to the style of others who appear to be emulating him).

Figure 0.1 Role reversal: A playful Antonio Banderas adjusts the director’s pose during the filming of ¡Atame! (Pedro Almodóvar, 1990; prod. El Deseo, S.A.) © El Deseo, S.A., S.L.U. © Jorge Aparicio.

In such a self-consciously public reencounter, the Cannes commentators could not resist conjuring up the respective pasts of the filmmaker and his lead actor, viewing their professional re-encounter in larger bio-filmic terms. Banderas’s star persona has taken shape as the result of a series of acting roles that rendered him an all-purpose Latin lover (Mambo Kings [Arne Glimcher, 1992]; Miami Rhapsody [David Frankel, 1995]); a parodic variant of the Latino swash-buckling hero (Desperado [Robert Rodríguez, 1995]; The Mask of Zorro [Martin Campbell, 1998]); a family man (Spy Kids [Gregorio Cortez, 2001] and its sequels); and most recently the reincarnation of a fairytale hero, but one without the claws or menace associated with his feline or Latin identity (beginning in Shrek 2 [Andrew Adamson et al., 2004) and continuing in its spin-off into the 2011 hit Puss ’n’ Boots [Chris Miller]). His presence as the iconic Latin male for Hollywood would pave the way for two other Spaniards, Penélope Cruz and Javier Bardem, also Almodóvar alumni, who could easily be recast either as Latin Americans, U.S. Latinos, or “others” by Hollywood screen writers and directors. All three would help forge the aura of star-maker around Almodóvar their mentor but it is Banderas, perhaps owing to his successful sexual polymorphism in Almodóvar’s early works, that could be understood to best embody and reflect Almodóvar’s career trajectory.

Figure 0.2 Banderas and Almodóvar relax on the set of La piel que habito (Pedro Almodóvar, 2011; prod. El Deseo, S.A.). © El Deseo, S.A., S.L.U. © Lucía Faraig.

The Banderas reunion with Almodóvar in La piel would bring into focus another bio-filmic dimension of the collaboration as it suggested to some critics a change in Amodóvar’s approach to one of his signature themes, sexuality. Banderas first appeared in Laberinto as a gay terrorist and was ironically marked in their subsequent films together as gay, heterosexual, or at times as sexually ambivalent.4 In this way he became a stand-in for the sexual and social fluidity central to Almodóvar’s early commercial filmmaking. That same fluidity is metonymically woven into the expanding Almodovarian narrative through the presence of transsexual characters who, initially, lean comic (Tina, played by Carmen Maura and her lesbian lover played by Bibi Anderson in La ley del deseo; Agrado [Antonia San Juan] in Todo sobre mi madre), and later, toward more tragic outcomes (Lola [Toni Cantó], also in Todo sobre mi madre; the adult Ignacio [Francisco Boira] in La mala educación). In La piel, it would seem, Almodóvar uses Banderas self-consciously to move those limits of gender in unexpected directions as Ledgard employs gender transfer as an act of revenge against the man who attempted to rape his daughter.

In this respect one may want to speak of Almodóvar’s “evolution,” to use the word his alter-ego, the romance novelist turned serious writer Leo (Marisa Paredes), uses in La flor de mi secreto/The Flower of My Secret (1995). Evolution for Leo meant precisely that shift from the popular vein to a presumed art discourse, what she calls at one point “las novelas que salen negras” (the novels that come out black), playing on the Spanish name for the romance novel form that made her career, “novela rosa.” The phrase foretells Almodóvar’s own aspirations in the face of his increasing success at home and abroad.5

To pin down the lines of that evolution, we might sketch out some of the important dates that mark the trajectory in the approximately twenty-year interval between Banderas’s departure for Hollywood and his return in La piel. The 1991 production of Tacones lejanos/High Heels marks the first of a series of collaborative projects with the French production company CIBY 2000, enabling Almodóvar to stabilize his presence both artistically and commercially with respect to the lucrative French market where he wins a César for the film and begins to cement a mainstream European status. This commercial alliance apparently also provides El Deseo, his production company founded in 1985, financial stability as he aspires to redefine himself beyond the narrow contexts of Spanish national cinema. It is arguably the “Frenchness” of the international Almodóvar which, in addition to his critical and commercial successes in the U.S. market, defines the transformation of the punk populist of the early Movida films into the European art cinema favorite he would later become.

In 1993, El Deseo takes on the production of Alex de la Iglesia’s first feature, Acción mutante/Mutant Action. This initiates a period of diversification in which Almodóvar is able, through his production company, to support the careers of other young Spanish directors (including Mónica Laguna, Daniel Calparsoro, Dunia Ayaso, and Félix Sabroso). This line of development culminates in 2003 with El Deseo’s production of the first of two English-language films by Isabel Coixet, My Life without Me/Mi vida sin mí. Importantly, these filmmakers are not mere surrogates for an Almodóvar school or genre; rather, they reflect the fact that his authorial self-construction has progressed beyond the individual and has become institutional. Thus, by the third decade of his career, it is clear that he has moved beyond the conventional sense of the film auteur as the name given to a visual/narrative style and has become deeply engaged in what Janet Staiger calls “Authorship as technique of the self” (2003: 49–52), by which she means the concept of the authorial as “the art of existence . . . a repetitive assertion of ‘self-as-expresser’ through culturally and socially laden discourses” (2003: 50). While still deeply engaged in developing his own creative trajectory, the expansion of his cinematic activities beyond his own work marks a redefinition of the author as commercial entrepreneur that will move him deeper into the realm of a commodity production (James 1989: 84). Rooted in that role is the implicit view that the auteur is tied to but not constrained either by genre or nation. This is a scenario worked out in multiple ways in Almodóvar’s cinema and reflected as well in the complex transformation of audiovisual culture during the last decade of the twentieth and first decade of the twenty-first centuries.

We witness a further realignment of the auteur with the entrepreneur in 1997 with the release of the first of three compilations of recorded songs from Almodóvar’s films, Las canciones de Almodóvar. This effort signals the beginning of a diversification project for the producer, El Deseo, and the expansion of the image of the filmmaker into a multimedia figure. Las canciones and the two subsequent CD compilations Viva la tristeza (2002) and B.S.O. Almodóvar (2007) differ from the customary movie soundtrack recordings of individual films that begin with Almodóvar’s collaborations with Ennio Morricone and Ryuichi Sakamtos in ¡Átame! and Tacones lejanos, respectively, and continue with Alberto Iglesias. Instead they function as independent signifiers of evolving creative agency, recontextualizing the music from his films around the figures of the singers whose careers he has helped reshape (Chavela Vargas) or whose posthumous fame (La Lupe) he has influenced in some way.

In 1999, Almodóvar earns the Oscar for Best Foreign Film for Todo sobre mi madre. While such recognition would for other auteurs represent the maximum achievement in international recognition, in this case the event confirms and celebrates the deterritorialization of Almodóvar’s cinema beyond its presumed Spanish origins, a process that has been ongoing throughout the previous decade but which is now brought more dramatically into public light. The year 2000 also marks a critical juncture in the broader global vocation of the auteur and his production company as El Deseo enters the Latin American market with a series of co-productions, principally through two key producers: Mexico’s Bertha Navarro and Argentina’s Lita Stantic. Over the next decade El Deseo will become the prestige producer for six Latin American films, providing them greater international access and visibility while enhancing its own position as a pan-Hispanic brand.

In 2002, Almodóvar wins the Oscar for Best Screenplay for Hable con ella/Talk to Her, an achievement even more significant than the award for Todo sobre mi madre in that it comes in a category in which he is in direct competition with U.S. screen writers. Again, the point is made that what is often perceived as the limiting imagination of the national (Higson 2000) has been largely superseded as Almodóvar’s corpus and career become fully integrated into world cinema.

In 2006 Almodóvar receives two distinct but significant marks of recognition that reflect the local/global dynamic that his career has assumed. He is awarded the Príncipe de Asturias Prize for the arts, the highest national award that a Spanish filmmaker can achieve, and in the spring of that same year, the Cinémathèque Française inaugurates a retrospective exhibition in Paris of his career: ¡Almodóvar Exhibition! This show, whose only antecedent for a Spanish filmmaker was the 2000 exhibition for the 100-year anniversary of Buñuel’s birth, underscores once again the unique transnational institutional status Almodóvar has achieved. In the continuing evolution of his authorial identity in response to radical changes in the technology, commerce, and art of cinema, Almodóvar appears to embody what Paul Julian Smith calls a “post-auteurist auteurism,” that bears little relation to the 1960s auteurism which, during much of his commercial career, had been the convenient way film scholars and commercial distributors of his films viewed his work. Rather, through an increasing absorption of a variety of mass media forms and new audiovisual formats, Almodóvar’s authorial presence expands as it migrates beyond cinema. At times, he will show himself resistant to the new technosphere involving multiple platforms for the circulation of his films and the cultivation of dialogue with his fan base through the internet. Yet he comes gradually to embrace an updated and intensified version of the entrepreneurial identity of one of his early authorial mentors, Andy Warhol,6 diversifying his authorial persona around the merging of art with cultural commerce.

In this tension between the traditional literary-inspired auteur and the author as cyber-phenomenon we may want to read back into the character of Ledgard an updating and expansion of the more conventional filmmakers-in-the-film who punctuate Almodóvar’s earlier work: Pablo Quintero in La ley del deseo; Max Espejo in ¡Átame!; Enrique Goded in La mala educación; or Harry Caine/Mateo Blanco in Los abrazos rotos. Ledgard needs to be included in that genealogy by virtue of his resemblance to earlier mythological and literary creators as well as the origin of “piel” which recasts his obsession with skin as a coded reference to Almodóvar’s obsession with that other skin, film. Yet what most separates him from his predecessors is the tacit recognition of the radical changes in the technologies of creation that are within his grasp. Though his desires are rooted in the past (the dream of restoring life to his lost wife and daughter), his means of retrieving that past move him to engage with the instrumentality of machines. Ledgard’s immersion in technological gadgetry is marked by a notable ambivalence that is perfectly embodied in the mise en scène of the plastic surgeon’s house. Dependent on the elaborate panoptic technology of surveillance equipment to spy on Vera at every moment, he views her on the larger-than-life closed-circuit monitor that hangs on the wall of his bedroom, a curious cross between a photograph and a filmic image. The walls of the hallway adjacent to Vera’s room are decorated with equally oversized framed images, the reproduction of Titian’s Venus of Urbino and Venus with the Organ Grinder, perfectly mirroring in the female subject’s posture Ledgard’s own view of his creation of Vera’s image in the classical pictorial terms of Titian’s reclining nudes. The painting, at once doubling the contemporary surveillance shot of the captive woman, harks back to an earlier age’s ways of figuratively “capturing” female beauty. This duality of scopic pleasures bespeaks the underlying tensions of Almodóvar’s own authorship, intimately rooted in a mastery of historical forms of creativity (the typewriter, celluloid, the photograph) but continually expanding its reach through new technologies.

The Companion to Pedro Almodóvar

The focus of this anthology of newly commissioned essays is an effort to identify and analyze the nuanced expressions of Almodóvar’s evolving authorship from a contemporary vantage point that takes into account the established language of auteurism—a recognizable visual style, thematic continuities—but also the expanded references and meanings that have emerged from the circulation of his works in recent decades into new geopolitical contexts and through redefined audiovisual media. A central concern is also the relation of art to commerce in the evolution of the Almodóvar phenomenon; though often commented on in terms of particular films, the “business” of Almodóvar’s art has seldom received the critical attention it is due as the engine that has contributed to his status as a matrix figure in contemporary culture.

The volume opens with a series of interrogations of the bio-filmic roots of Almodóvar’s self-invention as a film auteur, what Paul Julian Smith terms his cinematic “self-fashioning.” Smith looks to Los abrazos rotos to illustrate the ways one may read into certain of Almodóvar’s cinematic narratives a kind of deconstructive autobiography of the filmmaker’s personal life and professional career. This is more than simply a fanciful biographical fiction, as Smith contends; the cinematic allegory of Harry Caine, a.k.a. Mateo Blanco, is a many-sided mirror of the world of Almodóvar’s authorial creativity.

The young Almodóvar’s multimedia apprenticeship in both literary and cinematic contexts is excavated through Francisco Zurian’s examination of his earliest literary output: the unpublished short stories composed between Almodóvar’s arrival in Madrid in 1968 and his first experiments with Super-8 cinema in the mid-1970s. Read retrospectively, these stories provide a projection of the future Almodóvar: an eclectic talent who has moved across a variety of performance modes, yet remains firmly rooted in his prodigious talent as a storyteller.

Dona Kercher acknowledges a similar eclecticism as she traces the way the young filmmaker recycled key tropes from numerous Alfred Hitchcock’s films as these provided a primer during the years of Almodóvar’s autodidactic formation as auteur. More than a simple instance of plagiarisms from Hitchcock, as Kercher argues, the appropriation of visual tropes and narrative style that channel scenes and sequences from Hitchcock films and television work constitute an authentic apprenticeship in popular auteurist filmmaking.

Alberto Mira discerns that same dynamics of recycling at the heart of Almodóvar’s efforts at autobiographical reinvention. Reprising Smith’s notion of authorial self-fashioning through on-screen doubles, Mira contends that the filmmaker “is” in his films in the only way an artist can be said to be “in” his work: by putting together and turning into narrative a series of fragments of other texts, brought to life through cultural mythologies and a number of biographical anecdotes as a guarantee that the fiction is anchored in a “real” self. Those elements come together for Mira in the pivotal self-recycling of La mala educación.

This fanciful cinematic self-referentiality which runs through Almodóvar’s cinema, and even includes the director’s brief cameos in films that recall Hitchcock’s appearances in nearly of all his own films, helps to solidify a cluster of myths about Almodóvar’s creative identity. Such practices work effectively to establish Almodóvar as an international celebrity through the circulation of his films outside of Spain. Yet Almodóvar never fully disengages from his national cultural roots, a dimension explored in the section devoted to the Spanish contexts of his films. For Marina Díaz López, much of what we see as the tension between the local and global elements of style in his films is mirrored behind the scenes in the fortunes of the production company the director and his brother Agustín established in 1985. She argues that over time, El Deseo has consistently and often precociously responded to the fragmentation of Spanish media space by venturing into new media outlets. In the process, the company has operated as the “author’s brand” by supporting Spanish film auteurs and expanding their reach through co-productions with important Latin-American auteurs and with media-related Spanish businesses like the Barcelona-based MediaPro who share El Deseo’s approach to production and content.

Turning to the history of Almodóvar’s complex relations with the Spanish press, Josetxo Cerdán and Miguel Fernández assess three specific moments in the interplay between the self-taught, outsider director and a critical establishment schooled in the art cinema paradigms of the 1960s and 1970s. Through an analysis of the extensive promotional materials generated by Almodóvar and his production company and the often virulent critical response to both his films and the public projection of his celebrity persona, they identity the inadequacy of the narrow and largely antiquated criteria of high culture versus low and art versus folklore that Spanish movie reviewers have long employed in their denunciations of a complex cinema they fail to appreciate in terms of its creative amalgam of visual sophistication and traditionalist populism.

Stoking some of the recent antipathy toward Almodóvar at home are his public pronouncements on Spanish politics, particularly noteworthy in the wake of his presumed apoliticism—itself the object of much criticism—during the 1980s. Juan Carlos Ibáñez contests that frivolous surface image, which had been fueled by the director’s much cited claim that he made films as if Franco had never existed. He traces a set of textual references that reveal the essence of a much more complex, political Almodóvar. Taking La flor de mi secreto, Carne trémula/Live Flesh (1997) and La mala educación as the crucible of Almodóvar’s growing political maturity, his essay examines the expression of what he terms an “ethical postmodernity” that develops in Almodóvar’s films of the 1990s and enables the director’s critical rewriting of his own early career through the filter of the political disillusionment that has become a hallmark of contemporary Spanish cultural and political life.

Focusing on one of the central cultural and political reference points of that self-revision—that of historical memory—Adrián Pérez Melgosa examines the forms of retrospection and nostalgia, expressed in both subtle details and broad-brush strokes, that constitute the reflexive turn to the past in Almodóvar’s works. His analysis moves beyond plot details to reveal the evidence of a deeper concern with memory and trauma in a series of disruptive narrative devices and visual motifs: the embrace of anomalous temporalities, the privileging of apparently trivial objects, and the thematization of makeup and cosmetic alterations of the body.

This recent attention to Almodóvar’s more public political engagement notwithstanding, the principal signature of his auteurist identity throughout all periods of his career has been identified with the no less politically contentious area of sexuality and gender. This section of the book addresses four distinct limit cases of that signature theme structured around discussions of rape, paternity, violence, and gender transformation. Leora Lev focuses on the staging of sexual violence, arguing that Almodóvar’s representations of rape affirm an often misunderstood moral stance as the filmmaker dismantles and critiques, rather than espouses, gender essentialism by staging this act with grotesque, surreal, and darkly camp mise en scène. Importantly, she views his depiction of rape scenes as a critique of the media and its role in catering to consumer appetites for representations of sexual violence.

Dean Allbritton revisits Almodóvar’s radical envisioning of gender categories, one of the director’s characteristic tropes, analyzing the ways in which men and masculinity are insistently linked to illness, pathology, and death in his films. He considers these “pathogenic masculinities,” identified with the paternal archetype, as a contagious nexus for sickness and death, whereby the good health of the ideal male body is shaded with an illness that reproduces and gives birth to itself, thereby enabling a narrative, most notably in Todo sobre mi madre and Hable con ella, that affirms the fluidity between life and death as well as gender roles.

Noelia Saenz offers another approach to the representation of sexual violence in Almodóvar’s cinema, identifying a crucial shift away from the visualization of violence and erotic spectacle in Almodóvar’s films after Kika (1993) that is accompanied by a determination to consider the psychological and emotional impact of gendered violence. Similar to Lev, she discerns an evolution in the filmmaker’s moral positioning regarding sexual violence. Saenz argues that his treatment of domestic violence in his latter works coincides with a broader societal movement calling for the criminalization of gendered violence in Spain and its recognition as a human rights violation across the globe.

The moral dimensions of gender violence is at the heart of Francisco Zurian’s treatment of La piel que habito, as he underscores the way in which such violence, in this instance through the plastic surgeon’s scalpel, can transform the body but cannot touch an individual’s memory. The film thus becomes a reflection on the enduring strength of human identity, staged as a battle between the destructive power of art and science when harnessed to an unchecked ego and the moral and emotional power of the individual determined to resist such assaults and remain true to his or her memories.

Taking as a point of departure the complex webs of self-reference that operate within Almodóvar’s narrative world, the authors in the next section offer complex readings and re-readings of particular films against the broader backdrop of the evolving audiovisual narrative patterns of his work; their work thus reveals dominant structures which, in isolation, might otherwise be inaccessible. In the first essay Marsha Kinder turns to the intricate genealogy of the treatment of sound, especially speech, in Almodóvar’s films, focusing on “re-envoicement,” the act of combining “voices of authority” with “one’s own internally persuasive voice,” as a parallel auditory structure. She looks to Almodóvar’s privileging of certain sonic strategies, such as the uncoupling of voice and sound from image, in ways that resonate across his cinema, producing new forms of pleasure and meaning for audiences. In particular she examines the deployment of the maternal voice and its role in the negotiation of gender identities as developed through Almodóvar’s experimentation with the relation between sound and image

Celestino Deleyto focuses on the “mise en scène of desire” in a multi-protagonist narrative, Carne trémula, which he argues derives from earlier attempts to find a stylistic idiom to translate Almodóvar’s sexual ideology into filmic terms. For Deleyto this mise en scène is not so much a fantasized setting as primarily a series of visual and aural techniques which turn desire into cinema, and affect into an aesthetic object. At the same time, Deleyto reads the film as a pivotal moment in the director’s corpus as it looks forward to the stunning beauty and visual originality of his later films such as Hable con ella.

For Julián Daniel Gutiérrez-Albilla, La mala educación represents another catalyzing moment in the Almodóvar filmography with its complex reflections on the filmic encoding of personal and collective histories. Set against conventional readings of the film as fictionalized autobiography, Gutiérrez-Albilla’s analysis examines strategies that implicate cinema as the agency through which historical consciousness is self-referentially posited as a mediation of the traces of past traumas and as an embodied practice of witnessing the layers of memory that may even escape linguistic symbolization. His discussion of the ways the body reproduces experiences of personal and historical trauma folds back on the treatment of the body in earlier Almodóvar films. Most remarkably, although it was written several months before the release of La piel que habito, his essay offers an uncanny preview of the further textual imbrications of the body, and especially the skin, with memory in the latter film.