A Confluence of Minds E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

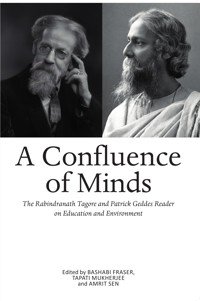

This collection of seminal correspondences between Indian Nobel Laureate Rabindranath Tagore and Scottish polymath Robert Geddes are testimony to a great friendship and an even greater marriage between Eastern and Western schools of thought. This compilation uncovers a confluence of ideas on the environment, science, rural reconstruction and a holistic approach to education that resonates with the lived experiences of its students.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 568

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Rabindranath Tagore on Patrick Geddes in his Foreword to Amelia Defries’s book,The Interpreter Geddes, the Man and the Gospel

First published in India 2017 by The Director, Granthan Vibhaga, Visva–Bharati

Revised edition first published in the UK 2018 by Luath Press

ISBN: 978-1-912387-36-6

The authors’ right to be identified as the authors of this book under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.

Typeset in 11 point Sabon by Lapiz

Photographs (except where indicated) courtesy of the Rabindra-Bhavana Archives

© the contributors

Contents

Foreword

Introduction

Rabindranath Tagore on Education

The Vicissitudes of Education (1892)

The Problem of Education (1906)

My School (1917)

The Centre of Indian Culture (1919)

An Eastern University (1921)

A Poet’s School (1926)

The Parrot’s Training (1918)

Sriniketan (1924)

The First Anniversary of Sriniketan (1924)

Patrick Geddes on Education

The World Without and the World Within (1905)

The Fifth Talk from my Outlook Tower: Our City of Thought

The Education of Two Boys

The Notation of Life

Scottish University Needs And Aims

Rabindranath Tagore on the Environment

The Religion of the Forest (1922)

Can Science Be Humanized? (1933)

The Relation of the Individual to the Universe (1913)

‘Introduction’ to Elmhirst’s address, ‘The Robbery of the Soil’

Patrick Geddes on the Environment

Cities, and the Soils They Grow from

The Valley Plan of Civilisation

V: Ways to the Neotechnic City

Life and its Science

The Sociology of Autumn

Letters

Plays and Poetry

Foreword

THE LATE19TH and early 20th century had witnessed the flowering of a Renaissance in Bengal and India with a vibrant connection with the West. The intellectual exchanges between Rabindranath Tagore and Patrick Geddes was part of this exchange. While both Tagore and Geddes were engaged with experimentations in education and the environment, they sought to radiate these experiments into their communities and beyond. Both shared a sense of globality and sought a free movement of ideas across borders.

The present volume brings some of these major ideas for the contemporary reader to appreciate the visionary qualities of these thinkers who alerted us to the dangers posed by rote education that was insensitive to the ecology and the community. While Geddes was more of a polemical writer, Rabindranath created a body of poetry and drama that could sensitize the audience to these issues.

Visva-Bharati and Edinburgh Napier University had collaborated on a UGC-UKIERI project titled ‘The Scotland India Continuum of Ideas: Tagore and his Circle’. The present volume is one of the two books that are being published on the basis of the project. This book is a collection of some of the most relevant writings of the two thinkers where there reveal the confluence of ideas; a separate volume will bring together critical evaluation of these ideas in contemporary times. Together these complementary volumes should provide a cohesive idea of the interface between these visionaries.

Since the volumes will address a global audience, most of the texts by Tagore have been cited from the English Writings of Rabindranath Tagore (in 4 vols.) published by Sahitya Akademi. Wherever we have used other translations, the source has been mentioned.

While we are deeply grateful to the UGC and UKIERI for funding the project, we would like to express our gratitude to Professor Swapan Dutta, Vice-Chancellor, Visva-Bharati and Professor Amit Hazra, Registrar Visva-Bharati for providing the necessary publication grant.

We sincerely hope that readers who are deeply committed to the cause of education and the environment will appreciate this volume.

Tapati Mukherjee & Amrit Sen

Santiniketan

Visva-Bharati

Rabindranath Tagore and Patrick Geddes: An Introduction to their Ideas on Education and the Environment

Neil Fraser and Bashabi Fraser

Rabindranath Tagore1 and Patrick Geddes were towering intellectuals from their respective nations, India and Scotland, and both polymaths, who had much in common, not least in their powerful thoughts on education and ecology. They met between 1918 and 1930 (as Geddes was in India for much of this time) and kept up a lively correspondence till Geddes’ death in 1932. As the letters reveal, they had a lot of respect for each other.2 Both were critical of the education around them, as they wanted close bonds with nature, and a regeneration of the land and improvements in the lives of villagers. Both reflected on the local but were also international in their outlook, especially in their thinking on the role of universities. But there are also contrasts between them, for Geddes was a scientist and a planner, whereas Rabindranath was first and foremost a creative artist. Rabindranath admired science and wanted it as a core subject in his university, but he was cautious with Geddes’ love of diagrams and ‘plans’. Geddes began his career in Botany, being a pioneer ecologist, but then moved more to the Social Sciences and was a Professor of Civics and Sociology in the University of Bombay. He did analytical scientific work, but with time, he became more interested in synthesizing the sciences, exploring their inter-relations. Rabindranath describes Patrick Geddes in a letter written on 4 August 1920, which is reproduced later on in this Reader: ‘What attracted me… was not his scientific achievements, but, on the contrary, the rare fact of the fullness of his personality rising far above his science. Whatever he has studied and mastered has become vitally one with his humanity.’ One could apply ‘fullness of personality’ and ‘one with his humanity’ to Rabindranath himself.

The focus on education and on environment was chosen for this Reader because of their centrality to the thinking and work of both men. Rabindranath was very unhappy about his own experience of formal education and went on to set up a school in 1901 and later a university, Visva-Bharati, established in 1921 at Shantiniketan.3 Geddes organized international summer schools for some twelve years in Edinburgh, was a consultant for planning universities, including Tagore’s own university and the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, and for a time organized home schooling for his own children, as did Rabindranath till his children were able to attend his school at Shantiniketan. In fact, Rabindranath and Geddes had experience of home schooling as boys, not just in pedagogic subjects but in diverse activities like wrestling and exercise on parallel bars in the case of Rabindranath and nature study with his father in their garden in the case of Geddes, and they both practised art at home.

Both men thus sought a holistic approach to education and emphasized harmony with nature. They stressed the need to nurture sympathy in human beings for their fellow beings and for their environment as they were concerned with the inter-relation between education and the environment, advocating ‘unity’. Geddes was a pioneer ecologist who taught about evolution and man’s responsibilities for conserving resources. Tagore wanted schooling which was close to nature and also wanted to improve the life of local villagers, whom he saw frequently suffering malaise which education, with university leadership, could help to address. Geddes too felt strongly about this and encouraged his son Arthur to take a leading part in it. They believed in the efficacy of science for a rounded education and in interdisciplinarity which did not compartmentalize humanities and the sciences. In their desire for holistic education and creative learning, they wanted poetry, music, painting and plays to be part of the curriculum, as exemplified by Rabindranath’s tireless writing of songs, poems, plays, operas and dance dramas which were performed by his students (and across Bengal) and Geddes’s pageants, masques and poetic exercises – which were published in The Evergreen.4

Rabindranath Tagore on Education:

An early essay (the ‘Vicissitudes of Education’, published when Rabindranath was 31) reflects his own experience of Indian education. He writes about the ‘joyless education our boys receive’, about ‘school work which is dull and cheerless, stale and unending’. He saw the major problem in the use of English as the medium of teaching and by teachers who were inadequately trained, and even given to physical punishment of their wards. He believed that education needs to be much closer to the students’ own lives, reflecting their experiences. Students are unable to cultivate thought or imagination when the education is imparted in a language and literature whose references are rooted in a culture they are unfamiliar with. The examples Rabindranath gives are of haymaking and of Charlie and Katie snowballing, which a Bengali child would be unable to imagine. The use of the Bengali language would help to ‘unite our language with our thought and our education with our life, ensuring a rootedness of education to the region where the child belonged’. Rabindranath speaks of the significance of Bankimchandra Chatterji’s Bangadarshan in this connection as a magazine that had characters and narratives a Bengali audience could identify with and relate to. The urgent need for schooling to be in the mother tongue remained a strong strand in the education policy formulated by Rabindranath.

As has been said earlier, Rabindranath established a school in Shantiniketan in rural Bengal, in the Birbhum district. In 1906 he wrote an essay ‘The Problem of Education’ where he notes that most schools function like factories, using mechanical methods that aimed at churning out products which were symmetrical, not recognizing the individuality of each child, and thus riding roughshod over each child’s creativity. He anticipates Foucault when he writes of ‘the prison walls of schools’. Schools need to get children interested, rather than offer an education that has no correspondence with what parents talk about at home. He advocates that teachers and pupils should live together and grow up with nature i.e. in schools which are not like closed institutions (e.g., prisons), but are close to ‘earth and water, sky and air’, in the spirit of the forest hermitage of ancient India, where the students lived with their Guru, their teacher, who was a family man and learning was a holistic experience involving shared daily chores as well as lessons.

In order to overhaul an unimaginative system of education, Rabindranath believes that the committed teacher is a prerequisite for good education, the teacher who encourages creativity and welcomes curiosity in his pupils. He is most critical of Bengali parents who bring up their children in an atmosphere that is divorced from their own culture and feels that the sons of the rich who are ferried to school and have their books carried for them, have their capacity for growth and freedom curbed and stunted: ‘Freedom is essential to the mind in the period of growth’. Pupils should do work in school gardens rather than be prepared for a life of a pampered elite. Children must learn simplicity like sitting on the floor, as plain living can free the learning environment from the clutter of equipment. In his school, where possible, the school still holds classes out-of-doors, each class meeting under the benign shade of a tree. In cities, Rabindranath recommends schools being built away from the congested parts, in green spaces where the child will learn about trees by climbing them, rather than from descriptions in text books, letting the joy of association with the natural surroundings making learning memorable and refreshing.

The philosophy of his school in Shantiniketan is developed by Rabindranath in ‘My School’, an essay published in 1917. He describes the object of education as ‘freedom of mind’ (children encouraged to think for themselves) and stresses the atmosphere or ethos of the school. In fact, in ‘A Poet’s School’ which he writes later, he says that what he has offered is an atmosphere where the child’s mind can grow feely and creatively. Shantiniketan is almost idyllic, a place where the children grow up amidst nature, a point that is stressed by Rabindranath as the ideal environment in its unfettered setting and expanse. Once again he stresses that schools should not be like factories and should not stifle love of life. He offers his students freedom and nurtures self-help. In this essay, Rabindranath offers a paean to the ideal teacher, who acts from a love and joy of life and literature, in Satish Chandra Ray, who came like a refreshing spring shower for a year to his institution at 19 and died at 20, but left a deep impression of how learning and play could be imperceptibly intertwined in an atmosphere of voluntary participation. He is Rabindranath’s ‘living teacher’. There is a unity in truth which means that there is no separation of the intellect from the spiritual and physical. Personality should be born of love, goodness and beauty. Here again he goes back to the forest hermitage, the tapovan, which he believes that India should ‘cherish’, this ‘memory of the forest colonies of great teachers’, where master (guru) and students shared ‘a life of high aspiration’. Here is the idea and practical realization of the campus university. As one pupil of Rabindranath’s institution, Amartya Sen, said ‘the emphasis here [in his school] was on self-motivation rather than on discipline, and on fostering intellectual curiosity rather than competitive excellence.’5 Another pupil, Mahasweta Devi, wrote ‘we were taught in our school that every animal, every cat, every bird, had a right to live. From childhood, we were taught to care for nature, not to break a single leaf or flower from a tree’.6

Rabindranath points out how Europe’s intellect and culture have their source in Europe from which its life blood flows, which informs and structures the education it offers in her educational institutions. Similarly, India’s source of light and life can only be found in India, in her past and in tracing a continuity in her evolution. Importing European education to India will prove stultifying and deny the growth of the Indian mind. He makes a difference between the conscious mind which is on the surface and the unconscious mind which is ‘fathomless’, the latter being the soul of man’s7 being which finds expression in poetry, music and art, underscoring man’s creative impulse which, in his collection of essays, The Religion of Man (1931), he identifies as his creative principle.

When Rabindranath published his essay ‘Centre of Indian Culture’ (1919) he was very much involved in the preparation of his international university, Visva-Bharati, a nest where the world meets. He envisaged Visva-Bharati as a centre of Indian culture, and not just being a centre of intellectual life but also a centre of economic life, as in rural reconstruction and also as an institution to which scholars and teachers from the West and East will come and participate in an atmosphere of mutual exchange. He recognised a need for a diversity of languages (as India has) and close connections with the cultures of other societies. He believed that music and art have to be part of culture and he established music and art as academic disciplines in his university. He also emphasized that there has to be room for all religions. He looked to Ireland in the Dark Ages for an example of education which flourished by having strong local roots (including the Irish language as a medium of instruction) while the rest of Europe was beset by war. The subsequent destruction of Irish seats of learning and the imposition of English on the nation, resulted in long years of suppression for Ireland.

After his visit to England in 1912 and the winning of the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1913, Rabindranath became a world figure travelling to several countries on invitation to address gatherings, and meet key people – intellectuals, artists and political leaders. Through his travels, interactions and writing, he strove to bring the East and West closer together through ‘co-ordination and co-operation’, ‘to unite the minds of the East and West in mutual understanding’ and to effect this, he speaks of having established an ‘Eastern University’ (Visva-Bharati) where the meeting of minds can effect a synthesis, bringing the closer world together. Synthesis is a term that Patrick Geddes uses in his own writing on education, one of the trio of ‘S’s that Geddes identifies, the other two being Sympathy which is also used by Rabindranath (as has, as has been noted earlier) and Synergy, which is generated by energetic activities.

In ‘An Eastern University’ (1921) Rabindranath discusses what universities should be. They should be places where East and West work together in the common pursuit of truth. Students from the west can study the different system of Indian philosophy, literature, art and music at Visva-Bharati. It should be a University which ‘will help India’s mind to concentrate and to be fully conscious of itself, free to seek the truth and make this truth its own wherever found, to judge by its own standard, give expression to its own creative genius, and offer its wisdom to the guests who come from other parts of the world’. The article also includes a critique of existing institutions of education.

In ‘A Poet’s School’ (1926) Rabindranath expands on the atmosphere he has sought to create in his school. He writes about learning to improvise and develop a creative life and finding freedom in nature. The school seeks to engage students in music, painting and drama in the open-air. It endeavours to counter assumptions many boys bring with them, e.g., that certain kinds of work are only to be done by a paid servant. The boys ‘take great pleasure in cooking, weaving, gardening, improving their surroundings, and in rendering services to other boys, very often secretly, lest they should feel embarrassed. Their classwork has not been separated from their normal activities but forms a part of their daily current of life.’ The school faced many obstacles e.g., parents’ expectations, the upbringing of teachers, the traditions of the ‘educated’ community, and the need to attract funding, but the atmosphere created helped to overcome these problems. The boys thus developed a sense of responsibility which forms the basis for a holistic education that assists character formation. The references in these essays are to ‘boys’ with whom the school at Shantiniketan was started. In subsequent years, girls were admitted to the school and the university became a mixed institution. In fact, the reputation of Rabindranath’s institution was such that Jawaharlal Nehru, the first Prime Minister of independent India, sent his daughter, Indira, to Rabindranath’s institution where she was educated for a year.

Many of India’s leading pre-independence and post-independence thinkers/scholars/artists have been educated at Shantiniketan, including such luminaries as the film director, Satyajit Ray8 who too has written about his debt to Rabindranath’s atmosphere of creative learning at his institution, which nurtured a knowledge and value of an education rooted in Indian tradition, the local, while being open to the ideas of the world.9 Of this experience Ray says, ‘I consider the three years I spent in Santiniketan as the most fruitful of my life… Santiniketan opened my eyes for the first time to the splendours of Indian and Far Eastern art. Until then I was completely under the sway of Western art, music and literature. Santiniketan made me the combined product of East and West that I am.’10

In the two edited sections from Rabindranath’s reflections in ‘Sriniketan’, which is the name of the Institute for Rural Reconstruction at Surul (Shantiniketan’s twin institution), he discusses why service to society should be part of education. He believes students and academics at universities should share a life with the tillers of the soil and that the humble workers in the villages should be part of an ideal educational institution. He advocates that human beings (both his students and the villagers) should be in infinite touch with nature in an atmosphere of service to all creatures, while practising a certain ‘detachment’ from the material world, gaining from a climate of uninhibited creativity which fosters a deep contact with (wo-)man’s ‘thought, emotion and will’.

The final piece in this section, is a delightful parable about education, called ‘The Parrot’s Training’, published earlier, in 1918. In this story, Rabindranath shows how the paraphernalia of education in elaborate buildings and equipment, can mean losing sight of the recipient of this whole exercise – the student – whose needs and propensities should be the central consideration in an educational system, but is sidelined by unimaginative and self-serving decision makers. In his ironic story, the king’s parrot is at first lively, singing and playful in its unrestricted setting, till the king’s advisors point out how cheeky and fearless the parrot is. On the advice of his ministers, the king decrees that things are put right to tame and teach the parrot a lesson. Everything is done for the parrot’s education from constructing a gilded cage, to providing a silver chain and finally clipping of the poor bird’s wings. The voice of the bird is no longer heard and when the king comes on an inspection tour of the progress of the bird’s education, he discovers the body of the tiny bird amidst this huge machinery, its mouth stuffed with pages from textbooks. Patrick Geddes was a strong admirer of this short-story as he calls for action against rote learning: ‘the Parrot be Avenged!’ (see his letter to Rabindranath written on 11 June 1908).

The letters between Rabindranath and Geddes, are a source for their ideas on education as well as the environment. For example, in Rabindranath’s letter to Geddes dated 9 May 1922, the former says that he started his school ‘with one simple idea, that education should never be dissociated from life’. He then says ‘the institution grew with the growth of my own mind and life’. He contrasts this organic approach to the planner’s approach adopted by Geddes, which he admires but temperamentally cannot adopt.

Patrick Geddes on Education

Like Tagore, Geddes was a critic of most existing schools. In his ‘The World Without and the World Within’ (1905) he argues most schools do not stimulate their students’ imaginations – the in-world of memories and plans is neglected – meaning they grow up unable to plan and therefore unable to act on the basis of plans. Geddes refers to the In-World of Memories and Plans against the Out-world of Facts and Acts. In ‘The Notation of Life’ he speaks of the Inner life. Rabindranath too speaks of the Inner Life and the Outer Life, ‘to distinguish between the quotidian life from the life of the mind’.11

In his ‘Our City of Thought’, Geddes discusses science and education. The strength of science is in its requirement to do fieldwork (systematic observation) – something education in science should practise (as shown by the Scottish medical scientist Joseph Lister and by the Scottish geologists). The diagnostic survey was a favourite tool of Geddes’ – recommended for example in town planning. But here he complains that too much of the education of the time teaches the non-empirical ways of old psychology or utilitarian economics. Science, in particular, needs direct contact with nature. Reflecting his own progress into the social sciences, Geddes argues that biology is a necessary preparation for sociology. He also argues that societies should be understood historically – even through the reading of ancient sacred texts for what they tell us of societies operating in a different environment from those of the present day.

In his ‘The Education of Two Boys’, he describes the home schooling for his own children, contrasting it with British public schools (‘standardising schools’). He talks about the wide range of occupations he took up in his youth and those of his children. Two of Geddes’ passions in his life came from his upbringing – the garden of his family home (leading to his passion for nature study and botany), and experimental methods, including data collection by survey (which he brought to his own practice as a town planner). The nature ramblings – as he had the freedom to scour his family garden in Perth and the landscape beyond along the Tay – developed his power of observation from this close association with his surroundings, making him the naturalist and humanist he was.

Geddes was a great believer in learning via recognizing the interdependence of academic subjects (see ‘The Notation of Life’). He developed elaborate diagrams to illustrate this inter-relatedness, diagrams that he called ‘Thinking Machines’. This simple but amazing method was adopted by Geddes when he briefly faced the threat of blindness and was unable to read or write in his usual copious manner. He then used a sheet of paper which he folded up into four and later nine sections and used each section to accommodate a thought which could be interlinked vertically, horizontally and diagonally to other thoughts, in what looked like a noughts and crosses pattern. A particular starting point he used for this ‘Thinking Machine’ was in showing the links between Place – Work – Folk (devised by the French sociologist, Le Play), the basis of the subjects Geography – Economics – Anthropology. Geddes sees Sociology as embodying all three. He came to Sociology from Biology, which he saw as a necessary preparation. An example of his recognition of the elements within Sociology is in his letter to Tagore on 15 April 1922, when he refers to ‘this diagram-plan of my department’. He goes on to say these subjects embody, in academic jargon, the ‘unity of life.’ Rabindranath, has, in different contexts, referred to ‘unity’ as the ultimate goal for mankind, of educational institutions with the surrounding country, of the urban with rural, of ‘man’ with nature, of ‘man’ with his fellow human beings. In his letter dated 9 May 1922, Rabindranath in his reply to Geddes’s letter, which is mentioned above, concedes that his university is not planned in this way; it is rather ‘a living growth’, what may be described as organic in its very development.

In his section on ‘Our City of Thought’, Geddes mentions the three stages in the development of people who have contributed to the progress of civilization, the ‘(1) Precursors, (2) Initiators (3) Continuators’, not in a steady mapable movement, as there have been ‘dormant periods’, but through continuators who have passed the torch of progress on ‘between initiative growth-waves’.

Like Rabindranath, he believes that science at city institutions cannot stay divorced from contact with nature which ensures the continuity of life, using the example of roses grown in flower vases, which is, untenable.

If our study is not in nature, of rocks, or forces, but like Ruskin’s in Venice, of the stones and human significance of cities, then shall we need to set our laboratory on their High Street; yet with scan of their plains to hills and sweep of the valley section of their civilization. So we shall come in the succeeding article more particularly to this Outlook Tower in Edinburgh. But before taking up its work of civic interpretation for city people.

In ‘The Education of Two Boys’ he mentions his own ‘curious perversion at 15’, when he was given to practical joking. It is an embarrassing memory, but he realizes that they were a result of him not finding an outlet for his creative mind, his restless curiosity which is channeled later on as he discovers his joy in creative learning. Thus in the summer he joined a ‘real joiner’s workshop’ in the mornings, followed by art school during the day and the laboratory in the evenings. This is what the adolescent needs, immersion in activities which occupy the mind and fire the imagination through practical methods of learning. He believes in a holistic education and is critical of a system that aims at creating ‘manly men’ rather than ‘man-in-the-universe.’ Speaking of his own children, he finds how journeys in a boat with a fisherman on the Tay, and learning to swim, led to his son joining a laboratory at Millport and his daughter becoming a student. With special reference to his son, he notes the boy’s natural instincts for discovering and exploring the world creatively, which bears fruit in his multifaceted talents finding expression in diverse endeavours and achievements, till his life is cut short tragically during his service in the First World War.

Patrick, with his younger son, Arthur Geddes, who went on to become a geographer, helped in the planning of Tagore’s university at Shantiniketan. Patrick’s letter to Tagore on 10 November 1922 sets out questions he needs to know (e.g. for how many students should they plan and for what departments should they plan?). He also enquires about the meaning of the International University. He refers Tagore to plans in Brussels and comments that they are a development of the annual summer schools in Edinburgh12, which he ran for a dozen years, attracting a range of well-known intellectuals (e.g., William James from Harvard).

Geddes’ belief that universities can play a crucial role in the renaissance of a country is to be found in his ‘Scottish University: Needs and Aims’. He argues there that Scotland then was behind the rest of Europe in reforming her universities. He gives two proposals which are notably sensitive to the needs of students: 1. The building of halls of residence (a project in which he had been actively involved in Edinburgh) and 2. Support for students studying abroad and in this connection, one can mention the later revival of the Scots College in Paris.

Rabindranath Tagore on the Environment

Much of Tagore’s thinking on the environment goes back to the forests which once covered India and the forest hermitages which developed there. He writes in ‘The Religion of the Forest’ about the kinship of man with creation:

The hermitage shines out, in all our ancient literature, as the place where the chasm between man and the rest of creation has been bridged. Nature stands on her own right, proving that she has her great function, to impart the peace of the eternal to human emotions.

Poets like Kalidasa are warning about the unreality of luxury in contrast to the purity of the forest. Tagore develops these thoughts in his essay ‘The Relation of the Individual to the Universe’. He contrasts the inspiration India draws from the simple life of the forest hermitage with the West’s idea of subduing nature. He emphasizes our harmony with nature. One poem included here is his ‘Homage to the Tree’. The goal of human life is to be peaceful and at-one-with-God. These ideals, shared by the Upanishads and Buddhism, are opposed to the policy of self-aggrandisement and greed that has motivated much human enterprise.

Greed is analysed by Rabindranath in his Introduction to Elmhirst’s address entitled, ‘The Robbery of the Soil’. With the rise of the standard of living in India, greed is encouraged, it ‘breaks loose from social control’. Cities are a prime cause, they are ‘unconscious of the devastation [they are] continuously spreading within the village’. A further factor identified is the rapid decay of India’s family system. The personal ambition of one member of the family is usually enough to lead to this decay. A career of plunder can outstrip ‘nature’s power for recuperation’. The result is exhaustion of water, cutting down of trees etc. – what is now termed desertification. Rabindranath took the evidence for these effects in the villages around Shantiniketan very seriously and believed universities should respond through community engagement and practical endeavour. He founded an Institute for Rural Reconstruction (Sriniketan) to address them, which was led by Leonard Elmhirst, an English agriculturalist with input from Arthur Geddes at one stage. Elmhirst gave an address about The Robbery of the Soil which Tagore introduced with the talk reproduced here. Elmhirst and Tagore both deplore a loss of community enterprise in many villages – evident in the lack of action to prevent erosion and to keep ponds clean. The result was poor crops leading to inadequate diets, which, coupled with the high prevalence of malaria and general lethargy, created a sense of despondency in the rural hinterland of Shantiniketen. Patrick Geddes’ son, Arthur, worked at Sriniketan for two years, doing teaching and village surveys, which assess and seek to address the situation (some of the surveys became the fieldwork for his PhD which he submitted later on at Montpellier, entitled Au Pays de Tagore ‘In the Land of Tagore’).

Patrick Geddes on the Environment

Understanding the environment was central to Geddes’ work throughout his life. He refers often to the central influence of the garden of his parents’ home in Perth and the countryside around it. Geddes believed that nature study should be a subject in schools and was responsible for initiating it in schools. Botany was his scientific discipline. Reilly has called him ‘one of the first modern ecologists’. He moved into social sciences (later becoming Professor of Civics and Sociology in the University of Bombay in 1920 as has been noted earlier) beginning from a belief that these sciences (sociology and economics) are a sub-species of biology. He believed rules of conduct for men could be derived from physical and biological laws. He recognized that resources like coal are finite and that one could have a balance-sheet for the sum of energy available. Resources need to be conserved. He sought to understand the issues created by a growing population (debating this with John Ruskin). Like Rabindranath he advocated co-operatives. He critiqued the economists’ use of ‘utility’ to measure the value of goods in favour of intrinsic value in terms of life-giving qualities.13

Geddes’ Talks from my Outlook Tower includes two essays on ecological themes. ‘Cities and the Soil They Grow From’(no.2), has a historical discussion of deforestation and malaria in the Mediterranean region, and the need for regional planning of afforestation. ‘The Valley Plan of Civilisation’(no.3), discusses the social significance of occupations according to topography between mountains and the sea. He discusses pastoral societies, wood-workers making tools, rice-growing, corn-growing, following a trajectory that signifies mankind’s progress and industries. Industrialisation changes, but does not obliterate, this analysis. In both these extracts Geddes adopts an approach based on economic stages of history, a particularly Scottish approach to analyzing history (as in Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations).

We have included a chapter from Patrick Geddes’ seminal publication, Cities in Evolution (1915). This discusses how town planning changed 19th century cities, ameliorating the grimness of the early industrial age (which Geddes called the paleotechnic age, a retrogressive step after the Neolithic stage). Beautifying cities tends to be dismissed as sentimental, but Geddes argues there is a good case for the conservation of nature, for creating parks in urban spaces and for the reclamation of slums within cities. We see that his experience of his parents’ garden in Perth and the green hinterland beyond which had beckoned him and aroused his naturalist’s enthusiasm remains a living memory in his town planning as he proposes breathing green spaces in urban scapes.

Geddes frequently takes up an argument that Arts and Sciences should not be compartmentalized. Two examples are in two issues of a short-lived journal he founded in 1895, The Evergreen. In the spring issue, entitled Life and its Science, he discusses how science on the one hand, and poetry and painting on the other, handle Nature and Life. He sees science in a process of rewriting its manuals. In poetic prose he describes how the beginning of life among insects, birds, and flowers in spring time happens: ‘As poetic intensity and poetic interpretation may be true at many deepening levels, so it is with the work of the painter; so too with the scientific study of nature’. We are invited to consider how research can throw new light on the problem of evolution and, in turn, how ideas of evolution can help us ‘re-organise the human hive’. And then through renewal of the environment, the painter and poet may find ‘new space for beauty and new stimulus of song’.

In the Autumn issue of The Evergreen, in ‘The Sociology of Autumn’, Geddes argues that analysis in art or science, can be rebuilt as synthesis. A favourite idea of Geddes is that understanding can be enhanced by looking into related areas/disciplines, a form of sympathy. He goes on to discuss synthesis in relation to cities, and particularly the seasons and cities. Autumn is viewed as the typical season of cities, being the season of both decadence and renewal (rebirth/renaissance), ‘autumn is the urban spring’ while ‘spring the urban autumn’. Geddes finishes with a sentence which might sum up his philosophy, the conclusion of Voltaire’s Candide, ‘we must cultivate our garden’. This can be the individual garden and the collective garden built through cooperation, which needs careful planning and nurture and which will bring about what Rabindranath calls, ‘creative unity’.

The sections on education and the environment are followed by selected letters which have been discussed where relevant in the above sections. The letters are followed by extracts of Rabindranath’s play, The Waterfall (Muktadhara) and a poem, ‘Homage to a Tree’, which embody the themes of this Reader.

The Waterfall ((Muktadhara) is a play by Tagore which anticipates the modern environmental concern over big dams. The arrogant royal engineer has built a machine (like a dam) to stop water from the waterfall. For him it has its own justification as a technological marvel (even though many are killed in its construction). But the real target of the dam seems to be to create drought conditions for a group of subjects (the Shiu-tarai) who are to be ‘punished’/displaced for having a different religion and appearance. The devotees of God Shiva are shown singing praises for victory. A schoolmaster is shown coaching his students to mouth aggressive cries against the Shiu-tarai uncomprehendingly, applauded by a government minister. The Crown Prince on the other hand sympathises with the Shiu-tarai and acts to destroy the machine, but he is swept away by the waters he releases. Through this self-sacrificing act, he restores freedom and dignity to his wronged subjects. The moral for man is not to try to subdue nature and not to treat a group of subjects as dispensable.

In the poem ‘Homage to The Tree’ Rabindranath meditates on trees as ‘friend of man’. The tree is symbolic of a living earth: ‘you urged a continuous war to liberate the earth from the fortress-prison of aridity.’ As a powerful Romantic poet, he recognizes its intrinsic aesthetic appeal ‘you were the first to sketch the living image of beauty’. In this poem we can see once again Rabindranath’s vision of the forest and the space it provides for reflection and growth as its trees show ‘how power can incarnate itself in peace’, the peace that comes from a silent and nurturing presence that embodies life.

Education and Environment were considerations that remained close to Rabindranath and Geddes’s life and thought, as reflected in their work, both in their writing and in their pragmatic and creative projects, the educational institutions they established, the socio-cultural issues they addressed, the continuity they saw as they evaluated tradition and embraced modernity. Both contributed to a sustainable future for humanity, through their belief in coordination and cooperation, through harmony and sympathy in a synthesis that puts mankind in touch with nature, challenges the rural-urban divide and gives educational institutions a key role in engaging with, gaining from and uplifting the surrounding environment through holistic education.

Neil Fraser

Bashabi Fraser

______________________

1. Henceforth Rabindranath. There were many Tagores who were illustrious, so in order to differentiate Rabindranath from the other talented members of his family, we will use his first name. In Bengal, writers and other famous men are mentioned by their first names, e.g., Bankimchandra (Chatterjee), Jagadish Chandra (Bose).

2. See Bashabi Fraser, Ed., The Tagore Geddes Correspondence (Shantiniketan: Visva-Bharati, India, 2004, 2nd Rev Edn) and A Meeting of Two Minds: the Geddes-Tagore Letters (Edinburgh: Wordpower Books, 2005), 3rd Rev Edn.

3. Rabindranath refers to it as Santiniketan. We have adopted Shantiniketan to indicate the way it is pronounced with a palatal ‘sh’ in Bengali.

4. Patrick Geddes, ed. The Evergreen, parts 1-4, 1895.

5. Amartya Sen, The Argumentative Indian: Writings on Indian Culture, History and Identity (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 2005), p.114

6. Quoted by Fakrul Alam and Radha Chakravarty, Eds., The Essential Tagore (Harvard and Visva-Bharati) from Mahasweta Devi, The Land of Cards p.viii, p.21.

7. Rabindranath’s use of the term ‘man’ encapsulates both women and men, which has subsequently been replaced by ‘human beings’.

8. Satyajit Ray was awarded the La Lumiere and won the Oscar for his lifetime’s work.

9. Patrick Geddes coined the slogan, ‘Think Global, Act Local’ in what has become impetus for glocality.

10. In Sen, p. 115. The spelling ‘Santiniketan’ is retained when quoting from the original texts which are referred/included to here.

11. Sabyasachi Bhattacharya, Rabindranath Tagore: An Interpretation (New Delhi: Penguin Books, 2011), ‘Introduction’, p. 7.

12. For an analysis of the significance of the correspondence between Geddes and Rabindranath, see Fraser, A Meeting of Two Minds, ‘Introduction’, pp. 12-51.

13. See J. P. Reilly, The Early Social Thought of Patrick Geddes, Ph.D. thesis (1972), ch. 2 &3, unpublished. New York: University of Columbia.

Rabindranath Tagore on Education

Rabindranath Tagore taking a class in Santiniketan

The Vicissitudes of Education (1892)14

HUMAN BEINGS CANNOT be content with the bare necessaries of life, and they are in fact partly chained to their needs and partly free. The average man is three and a half cubits tall, but he lives in a house that is much taller, and has plenty of room for the freedom of movement so essential for health and comfort. This applies equally to education. A boy should be allowed to read books of his own choice in addition to the prescribed text-books he must read for his school-work. His mental development is likely to be arrested if he is not allowed to do this, and he may grow into a man with the mind of a boy.

Unfortunately a boy in this country has very little time at his disposal. He must learn a foreign language, pass several examinations, and qualify himself for a job, in the shortest possible time. So, what can he do but cram up a few text-books with breathless speed? His parents and his teachers do not let him waste precious time by reading a book of entertainment, and they snatch it away from him the moment they see him with one.

An unkind fate has ruled that the Bengalee boy shall subsist on the lean diet of grammar, lexicon, geography. To see him in the class room, his thin legs dangling from his seat, is to see the most unfortunate child in the world. At an age when children of other countries are having all sorts of treats, he must digest his teacher’s cane with no other seasoning that the teacher’s abuse.

That sort of fare is sure to ruin anybody’s digestive organs, and there can be no doubt that for lack of nourishment and recreation the Bengalee boy grows up without fully developing his physical and mental powers. That explains why, although many of us take the highest university degrees and write many books, we as a people have minds that are neither virile nor mature. We cannot get a proper hold on anything, cannot make it stand firm, cannot build it up from bottom to top. We do not talk, think, or act like adults, and we try to cover up the poverty of our minds with overstatement, ostentation and swagger.

This is due mainly to the joyless education our boys receive from childhood onwards, learning a few prescribed text-books by heart, and acquiring a working knowledge of a few subjects instead of mastering them. Human beings need food, and not air, to satisfy their hunger, but they also need air properly to digest their food. Many books of entertainment are likewise necessary for a boy properly to digest one text-book. When a boy reads something for pleasure, his capacity for reading increases imperceptibly, and his powers of comprehension, assimilation and retention grow stronger in an easy and natural manner.

Language is our first difficulty. Because of the many grammatical and syntactical differences between English and our mother-tongue, English is very much a foreign language to us. Then there is the difficulty connected with the subject matter, which makes an English book doubly foreign to us. Utterly unfamiliar with the life it describes, all we can do is to get the text by rote without understanding it – with the same result as that of swallowing food without chewing it. Suppose a children’s Reader in English contains a story about haymaking, and another about a quarrel that Charlie and Katie had when they were snowballing. These stories relate incidents familiar to English children, and are interesting and enjoyable to them; but they rouse no memories in the minds of our children, unfold no pictures before their eyes. Our children simply grope about in the dark when reading these books.

A further difficulty stems from the fact that the men who teach the lower forms of our schools are not adequately trained for their work. Some of them have only passed the Matriculation examination, some have not even done that, and all are lacking adequate knowledge of English language and literature, English life and thought. Yet these are the teachers to whom we owe our introduction to English learning. They know neither good English nor good Bengali, and the only work they can do is misteaching.

Nor can we really blame the poor men. Suppose I have to put the sentence ‘The horse is a noble animal’ into Bengali. How shall I do it? Shall I say the horse is a ‘great’ animal, a ‘high class’ animal, a ‘very good’ animal, or what? None of the Bengali words for ‘noble’ I can think of seem right, but in the end I shall probably resort to downright cheating. So I cannot really blame the teacher if in the end he resorts to a dodge.

The result is that the boy learns nothing. Had he been learning no other language than Bengali, he would at least have been able to read and appreciate the Ramayana and Mahabharata. Had he not been sent to school at all, he would have had all the time in the world to play games, climb trees, swim in the rivers and ponds, pluck flowers, and do a thousand damages to fields and woods. He would thus have fully gratified his youthful nature and developed a cheerful mind and a healthy body. But as he struggles with his English, neither does he learn it, nor does he enjoy himself; neither does he acquire the ability to enter the imaginary world of literature, nor does he get the time to step into the real world of nature.

Man belongs to two worlds, one of which lies within him and the other outside. They give him life, health and strength and keep him ever-flowering by ceaselessly breaking upon him in waves of form, colour and smell, movement and music, and love and joy. Our children are banished from both these worlds, as from two native lands, and are kept chained in a foreign prison. God has filled the hearts of parents with love so that children can have their fill of it, and He has made the breasts of mothers soft so that children can rest on them. Children have small bodies but all the empty spaces of the house do not give them enough room to play. And where do we make our sons and daughters spend their childhood? Among the grammars and lexicons of a foreign language; and within the narrow confines of a school work which is dull and cheerless, stale and unending.

A man’s years are like links in a chain, and it will be somewhat superfluous to state anew the well-known fact that childhood grows into manhood by degrees. Certain mental qualities are indispensable to a grown-up man who has just entered the world of action. But these qualities are not instantly available; they have to be developed. Like our hands and feet our mental qualities grow at every stage of our life in answer to the call that is made on them. They are not like ready-made articles which can be bought in shops whenever needed.

The power of thought and the power of imagination are indispensable to us for discharging the duties of life. We cannot do without those two powers if we want to live like real men. And unless we cultivate them in childhood we cannot have them when we are grown up.

Our present system of education, however, does not allow us to cultivate them. We have to spend many years of our childhood in learning a foreign language taught by men not qualified for the job. To learn the English language is difficult enough, but to familiarize ourselves with English thought and feeling is even more difficult, and takes a long time during which our thinking capacity remains inactive for lack of an outlet.

To read without thinking is like accumulating building materials without building anything. After we have accumulated a mountainous pile of mortar, lime and sand, and of bricks, beams and rafters, we suddenly get an order from the University to do the roof of a three-storied house. So we instantly climb to the top of our pile and beat it down incessantly for two years, until it becomes level and somewhat resembles the flat roof of a house. But could this pile be called a house? Has it windows to let in air and light? Could a man make it his home for the whole of his life? Has it order, beauty, harmony?

There is no doubt that a great deal of material is now collected in our country for building the edifice of the mind, much greater than at any other time in its history. But we must not make the mistake of thinking that by learning to collect we have learnt to build. Good results follow only when accumulation and building are carried on, step by step, at the same time.

It follows, therefore, that if I want my son to grow up into a man, I should see that he grows up like a man right from his childhood. Otherwise he will always remain a child. He should be told not to rely entirely on memory, and be given plenty of opportunity to think for himself and use his imagination. To get a good crop it is necessary to water the field besides ploughing it and harrowing it, and rice in particular grows best on well-watered earth. Rain is essential to rice at a particular moment in its cultivation, and the crop will be ruined if there is no rain when it is needed most. When the moment is gone, even a lot of rain will not save the crop. Childhood and adolescence are the moments when the stimulus of literature is essential to the growth of a man. Quickened by that stimulus, the tender shoots of his mind and heart will come forth in the air and light, and continue to grow in health and strength. But they will remain undeveloped if the moment is wasted in studying dry and dusty grammars and lexicons. Even if the most vital truths, wonderful conceptions, and sublime thoughts of European literature are showered on the man for the rest of his life, he will never imbibe its inmost spirit.

In our lives that auspicious moment is wasted in joyless education. From childhood to adolescence, and again from adolescence to manhood, we are coolies of the goddess of learning, carrying loads of words on our folded backs. When at last we manage to enter the realm of English ideas, we find that we are not quite at home there. We find that although we can somehow understand those ideas, we cannot absorb them into our deepest nature; that although we can use them in our lectures and writings, we cannot use them in the practical affairs of our lives.

So the first twenty or twenty-two years of our lives are spent in picking up ideas from English books. But at no time are those ideas chemically fused with our lives. The result is that our minds present a most bizarre look, some of those ideas sticking to them like pieces of gummed paper while others have been rubbed off in course of time. After smearing ourselves with a European learning which has no connection with our inner lives, we strut about as proudly as those savages who ruin the natural brightness and loveliness of their skin by painting and tattooing it. Savage chiefs do not realize how ridiculous they look when they put on European clothes and decorate themselves with cheap European glass beads. We too do not realize what unconscious figures of farce we become when we parade the cheap smartness of the English words we know, and ruin some of the greatest European ideas by completely misapplying them. If we see anyone laughing at us, we immediately try to justify ourselves by speaking even more impressively.

Since our education bears no relation to our life, the books we read paint no vivid pictures of our homes, extol no ideals of our society. The daily pursuits of our lives find no place in those pages, nor do we meet there anybody or anything we happily recognize as our friends and relatives, our sky and earth, our mornings and evenings, or our cornfields and rivers. Education and life can never become one in such circumstances, and are bound to remain separated by a barrier. Our education may be compared to rainfall on a spot that is a long way from our roots. Not enough moisture seeps through the intervening barrier of earth to quench our thirst.

The barrier that separates education from life is really impenetrable in this country, so that their union is hard to attain. A growing hostility between the two is most often the result. We begin to develop a fundamental dislike and distrust of what we learn at school and college, since we find it contradicted in every detail by the conditions of the life around us. We begin to think that we are learning untruths and that European civilization is wholly based on them; that Indian civilization is wholly based on truth and our education is directing us to a land of enchanting falsehood. The real reason why European learning often fails us is not to be sought in any defect in that learning, but in the unfavourable conditions of our life. Yet we say that European learning fails us because failure is inherent in its nature. The stronger our dislike of this learning, the fewer the benefits it confers on us. And so the feud between our education and our life sharpens. As they draw further apart, our days become a stage where they mock and revile each other like two characters in a farce.

How to effect the union of education and life is today our most pressing problem. That union can be achieved only by Bengali language and literature. We all know that Bankimchandra Chatterji’s periodical, Bangadarshan, appeared in the sky of Bengal like the dawn of a new day. Why was it that it gave the entire educated class such deep satisfaction? Did it publish any truth hitherto unknown to European history, philosophy or science? The answer is that Bangadarshan was the instrument with which a great genius broke down the barrier between our education and our life, and effected the joyous union of our head and heart. Until then, European culture had been an alien amongst us. As Bangardarshan brought it into our homes, we began to see ourselves in a new, revealing light. In the figures of Suryamukhi and Kamalmani, Bangardarshan showed our women as they really are; in the characters of Chandraesekhar and Pratap, it raised the ideal of Bengali manhood; and it cast a ray of glory on the petty affairs of our day-to-day life.

The pleasure we derived from Bangadarshan has had the effect of making educated Bengalees of today eager to write in their mother-tongue. They have realized that English can serve only their business, and not literary purposes; and they have noticed that, in spite of the great care with which English is learnt in this country, the books that are likely to live a long time are all being written in Bengali. The main reason for this is that a Bengalee can never acquire so close and intimate a knowledge of English as to make it the medium of a spontaneous literary expression. Even if he were a master of the English language, he would not be able to make it a live instrument of Bengali thought and feeling. The uncommon beauties and memories that impel us to creative activity can never assume their true form in a foreign language. Nor can those inherited qualities, which through generations have cast our minds in a special mould.

I have already said that our childhood and adolescence are spent in learning a language without gaining access to the underlying thought. The situation is reversed when we are older; we then lack a language with which to express our thoughts. I have also said that the reason why we are never on intimate terms with English literature is to be found in the dissociation of language and thought that takes place in us early in life. It is also the reason why many of our latter-day intellectuals feel dissatisfied with English literature. Turning to these intellectuals, we find that their thought is dissociated not only from English, but from Bengali as well. They have in fact become strangers to Bengali and developed an aversion for it. They do not, of course, openly admit that they do not know it, and they cry it down as unsuitable for thoughtful work and unworthy of cultivated people like themselves. It is the story of sour grapes over again.

From whatever angle we consider the matter, we find that our life, our thought and our language are not harmonized. Because of this fundamental disunity, we cannot stand on our two feet, cannot get what we want, cannot succeed in our efforts. I once read a story of a poor man who wanted to buy himself winter clothes for winter and summer clothes for summer. So he used to save up all the money he could get by begging. But he could not save up enough to buy summer clothes until summer was gone. This went on year after year until God, moved by pity, told the man that He would grant him a wish. ‘All I ask for,’ the man said, ‘is this: let the vicissitudes of fortune end, so that I no longer get winter clothes in summer and summer clothes in winter.’

We too pray that God would end the vicissitudes of our education, and grant us winter clothes in winter and summer clothes in summer. God has put before us everything we need, but we cannot help ourselves to the right thing at the right moment. And that is why we live like that beggar in the story. So let us pray to God to give us food, when we are hungry, and clothes when we are cold. Let us pray that He would unite our language with our thought and our education with our life.

______________________

14. Rabindranath Tagore Towards Universal Man ed. Humayun Kabir, (Asia Publishing house, 1961) pp 39-48.

The Problem of Education (1906)15

WHAT WE NOW