6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: No Exit Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

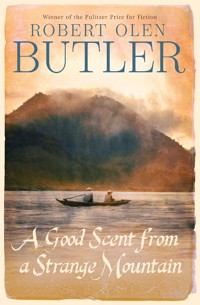

Robert Olen Butler's lyrical and poignant collection of stories about the aftermath of the Vietnam War and its impact on the Vietnamese was acclaimed by critics across the nation and won the Pulitzer Prize in 1993. A contemporary classic by one of America's most important living writers, this edition of A Good Scent from a Strange Mountain includes two subsequently published stories that brilliantly complete the collection's narrative journey, returning to the jungles of Vietnam.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

Robert Olen Butler's lyrical and poignant collection of stories about the aftermath of the Vietnam War and its impact on the Vietnamese was acclaimed by critics across the nation and won the Pulitzer Prize in 1993.

A contemporary classic by one of America's most important living writers, this edition of A Good Scent from a Strange Mountain includes two subsequently published stories – ‘Salem’ and ‘Missing’ - that brilliantly complete the collection's narrative journey, returning to the jungles of Vietnam.

CRITICAL ACCLAIM FOR A GOOD SCENT FROM A STRANGE MOUNTAIN

‘This book has attracted such acclaim not simply because it is beautifully and powerfully written, but because it convincingly pulls off an immense imaginative risk… Butler has not entered the significant and ever-growing canon of Vietnam-related fiction (he has long been a member) – he has changed its composition forever’ – Guardian

‘It is the Vietnamese voice that Butler seeks and that, in these stories, he has so remarkably and movingly found’ – Los Angeles Times

‘Delicately moving… Each of the fifteen stories brings us a sharp impression of a different person, speaking magically to us across the silent page’ – New York Newsday

‘Funny and deeply moving… One of the strongest collections I’ve read in ages’ – Ann Beattie

‘An extraordinary book… [Butler] has managed to depict both Vietnam and Louisiana simultaneously in stories that have the delicate and graceful quality of tropical flowers’ – James Lee Burke

ROBERT OLEN BUTLER served with the US Army in Vietnam as a Vietnamese linguist in 1971. He is the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of A Good Scent from a Strange Mountain, five other short story collections, sixteen novels, and a book on the creative process, From Where You Dream. A recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship in fiction, he also won the Richard and Hinda Rosenthal Foundation Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. He has twice won a National Magazine Award in Fiction and has received two Pushcart Prizes. Robert Olen Butler has also trained as an actor, worked as a reporter, and engaged in intelligence collection. In 2013 he won the F. Scott Fitzgerald Award for Outstanding Achievement in American Literature. He teaches creative writing at Florida State University.

www.roboertolenbutler.com

A GOOD SCENT FROM A STRANGE MOUNTAIN

Also by Robert Olen Butler

The Alleys of Eden

Sun Dogs

Countrymen of Bones

On Distant Ground

Wabash

The Deuce

A Good Scent from a Strange Mountain

They Whisper

Tabloid Dreams

The Deep Green Sea

Mr. Spaceman

Fair Warning

Had a Good Time

From Where You Dream: The Process of Writing Fiction

(Janet Burroway, Editor)

Severance

Intercourse

Hell

Weegee Stories

A Small Hotel

The Hot Country

The Star of Istanbul

The Empire of Night

A GOOD SCENT FROM A STRANGE MOUNTAIN

Stories by

Robert Olen Butler

For John Wood, my Friend and Colleague

CONTENTS

Open Arms

Mr Green

The Trip Back

Fairy Tale

Crickets

Letters from my Father

Love

Mid-Autumn

In the Clearing

A Ghost Story

Snow

Relic

Preparation

The American Couple

A Good Scent from a Strange Mountain

Salem

Missing

The stories in this book have appeared in the following pages: ‘Open Arms,’ The Missouri Review; ‘Mr Green,’ The Hudson Review; ‘The Trip Back,’ The Southern Review, reprinted in the 1991 edition of The Best American Short Stories; ‘Fairy Tale,’ The Virginia Quarterly Review; ‘Crickets,’ syndicated by PEN and broadcast on National Public Radio’s ‘The Sound of Writing’; ‘Letters from My Father,’ Cimarron Review; ‘Love,’ Writer’s Forum; ‘Mid-Autumn,’ Hawaii Review; ‘In the Clearing,’ Icarus; ‘A Ghost Story,’ Colorado Review; ‘Snow,’ The New Orleans Review; ‘Relic,’ The Gettysburg Review, reprinted in New Stories from the South, The Year’s Best 1991; ‘Preparation,’ The Sewanee Review, reprinted in New Stories from the South, The Year’s Best 1992; ‘A Good Scent from a Strange Mountain,’ New England Review, reprinted in the 1992 edition of Best American Short Stories and New Stories from the South, The Year’s Best 1992; ‘Salem,’ Mississippi Review, reprinted in the 1996 edition of The Best American Short Stories; ‘Missing,’ Gentlemen’s Quarterly.

OPEN ARMS

I have no hatred in me. I’m almost certain of that. I fought for my country long enough to lose my wife to another man, a cripple. This was because even though I was alive, I was dead to her, being far away. Perhaps it bothers me a little that his deformity was something he was born with and not earned in the war. But even that doesn’t matter. In the end, my country itself was lost and I am no longer there and the two of them are surely suffering, from what I read in the papers about life in a unified Vietnam. They mean nothing to me, really. It seems strange even to mention them like this, and it is stranger still to speak of them before I speak of the man who suffered the most complicated feeling I could imagine. It is he who makes me feel sometimes that I am sitting with my legs crossed in an attitude of peace and with an acceptance of all that I’ve been taught about the suffering that comes from desire.

There are others I could hate. But I feel sorry for my enemies and the enemies of my country. I live on South Mary Poppins Drive in Gretna, Louisiana, and since I speak perfect English, I am influential with the others who live here, the Westbank Vietnamese. We are all of us from South Vietnam. If you go across the bridge and into New Orleans and you take the interstate north and then turn on a highway named after a chef, you will come to the place called Versailles. There you will find the Vietnamese who are originally from the North. They are Catholics in Versailles. I am a Buddhist. But what I know now about things, I learned from a communist one dark evening in the province of Phước Tuy in the Republic of South Vietnam.

I was working as an interpreter for the Australians in their base camp near Núi Đầt. The Australians were different from the Americans when they made a camp. The Americans cleared the land, cut it and plowed it and leveled it and strung their barbed wire and put up their tin hootches. The Australians put up tents. They lived under canvas with wooden floors and they didn’t cut down the trees. They raised their tents under the trees and you could hear the birds above you when you woke in the morning, and I could think of home that way. My village was far away, up-country, near Pleiku, but my wife was still my wife at that time. I could lie in a tent under the trees and think of her and that would last until I was in the mess hall and I was faced with eggs and curried sausages and beans for breakfast.

The Australians made a good camp, but I could not understand their food, especially at the start of the day. The morning I met Đặng Văn Thập, I first saw him across the mess hall staring at a tray full of this food. He had the commanding officer at one elbow and the executive officer at his other, so I knew he was important, and I looked at Thập closely. His skin was dark, basic peasant blood like me, and he wore a sport shirt of green and blue plaid. He could be anybody on a motor scooter in Saigon or hustling for xích-lộ fares in Vũng Tàu. But I knew there was something special about him right away.

His hair was wildly fanned on his head, the product of VC field-barbering, but there was something else about him that gave him away. He sat between these two Australian officers who were nearly a head taller, and he was hunched forward a little bit. But he seemed enormous, somehow. The people in our village believe in ghosts. Many people in Vietnam have this belief. And sometimes a ghost will appear in human form and then vanish. When that happens and you think back on the encounter, you realize that all along you felt like you were near something enormous, like if you came upon a mountain in the dark and could not see it but knew it was there. I had something of that feeling as I looked at Thập for the first time. Not that I believed he was a ghost. But I knew he was much bigger than the body he was in as he stared at the curried sausages.

Then there was a stir to my left, someone sitting down, but I didn’t look right away because Thập held me. ‘You’ll have your chance with him, mate,’ a voice said in a loud whisper, very near my ear. I turned and it was Captain Townsend, the intelligence officer. His mustache, waxed and twirled to two sharp points, twitched as it usually did when he and I were in the midst of an interrogation and he was getting especially interested in what he heard. But it was Thập now causing the twitch. Townsend’s eyes had slid away from me and back across the mess hall, and I followed his gaze. Another Vietnamese was arriving with a tray, an ARVN major, and the C.O. slid over and let the new man sit next to Thập. The major said a few words to Thập and Thập made some sort of answer and the major spoke to the C.O.

‘He’s our new bushman scout,’ Townsend said. ‘The major there is heading back to division after breakfast and then we can talk to him.’

I’d heard that a new scout was coming in, but he would be working mostly with the units out interdicting the infiltration routes and so I hadn’t given him much thought. Townsend was fumbling around for something and I glanced over. He was pulling a slip of paper out of his pocket. He read a name off the paper, but he butchered the tones and I had no idea what he was saying. I took the paper from him and read Thập’s name. Townsend said, ‘They tell me he’s a real smart little bastard. Political cadre. Before that he was a sapper. Brains and a killer, too. Hope this conversion of his is for real.’

I looked up and it was the ARVN major who was doing all the talking. He was in fatigues that were so starched and crisp they could sit there all by themselves, and his hair was slicked into careful shape and rose over his forehead in a pompadour the shape of the front fender on the elegant old Citroën sedans you saw around Saigon. Thập had sat back in his chair now and he was watching the major talk, and if I was the major I’d feel very nervous, because the man beside him had the mountain shadow and the steady look of the ghost of somebody his grandfather had cheated or cuckolded or murdered fifty years ago and he was back to take him.

It wasn’t until the next day that Captain Townsend dropped Thập’s file into the center of my desk. The desk was spread with a dozen photographs, different angles on two dead woodcutters that an Australian patrol had shot yesterday. The woodcutters had been in a restricted area, and when they ran, they were killed. The photos were taken after the two had been laid out in their cart, their arms sprawled, their legs angled like they were leaping up and clicking their heels. The fall of Thập’s file scattered the photos, fluttered them away. Townsend said, ‘Look this over right away, mate. We’ll have him here in an hour.’

The government program that allowed a longtime, hard-core Viet Cong like Thập to switch sides so easily had a stiff name in Vietnamese but it came to be known as ‘Open Arms.’ An hour later, when Thập came through the door with Townsend, he filled the room and looked at me once, knowing everything about me that he wished, and the idea of our opening our arms to him, exposing our chests, our hearts, truly frightened me. In my village you ran from a ghost because if he wants you, he can reach into that chest of yours and pull out not only your heart but your soul as well.

I knew the facts about Thập from the file, but I wondered what he would say about some of these things I’d just read. The things about his life, about the terrible act that turned him away from the cause he’d been fighting for. But Townsend grilled him, through me, for an hour first. He asked him all the things an intelligence captain would be expected to ask, even though the file already had the answers to these questions as well. The division interrogation had already learned all that Thập knew about the locations and strengths of the VC units in our area, the names of shadow government cadre in the villages, things like that. But Thập patiently repeated his answers, smoking one Chesterfield cigarette after another, careful about keeping his ash from falling on the floor, never really looking at either of us, not in the eye, only occasionally at our hands, a quick glance, like he expected us to suddenly be holding a weapon, and he seemed very small now, no less smart and skilled in killing, but a man, at last, in my eyes.

So when Captain Townsend was through, he gave me a nod and, as we’d arranged, he stepped out for me to chat with Thập informally. Townsend figured that Thập might feel more comfortable talking with his countryman one on one. I had my doubts about that. Still, I was interested in this man, though not for the reasons Townsend was. At that moment I didn’t care about the tactical intelligence my boss wanted, and so even before he was out of the room I intended to ignore it. But I felt no guilt. He had all he needed already.

As soon as the Australian was gone, Thập lifted his face high for the first time and blew a puff of smoke toward the ceiling. This stopped me cold, like he’d just sprung an ambush from the undergrowth where he’d been crouching very low. He did not look at me. He watched the smoke rise and he waited, his face placid. Finally I felt my voice would come out steady and I said, ‘We are from the same region. I am from Pleiku Province.’ The file said that Thập was from Kontum, the next province north, bordering both Cambodia and Laos. He said nothing, though he lowered his face a little. He looked straight ahead and took another drag on his cigarette, a long one, the ash lengthening visibly, doubling in size, as he drew the smoke in.

I knew from the file the sadness he was bearing, but I wanted to make him show it to me, speak of it. I knew I should talk with him indirectly, at least for a time. But I could only think of the crude approach, and to my shame, I took it. I said, ‘Do you have family there?’

His face turned to me now, and I could not draw a breath. I thought for a moment that my first impression of him had been correct. He was a ghost and this was the moment he would carry me away with him. My breath was gone, never to return. But he did not dissolve into the air. His eyes fixed me and then they went down to the file on the desk, as if to say that I asked what I already knew. He had been sent to Phước Tuy Province to indoctrinate the villagers. He was a master, our other sources said, of explaining the communist vision of the world to the woodcutters and fishermen and rice farmers. And meanwhile, in Kontum, the tactics had changed, as they always do, and three months ago the VC made a lesson out of a little village that had a chief with a taste for American consumer goods and information to trade for them. This time the lesson was severe and the ones who did not run were all killed. Thập’s wife and two children expected to be safe because someone was supposed to know whose family they were. They stayed and they were murdered by the VC and Thập made a choice.

His eyes were still on the file and my breath had come back to me and I said, ‘Yes, I know.’

He turned away again and he stared at the cigarette, watched the curl of smoke without drawing it into him. I said, ‘But isn’t that just the war? I thought you were a believer.’

‘I still am,’ he said and then he looked at me and smiled faintly, but the smile was only for himself, like he knew what I was thinking. And he did. ‘This is nothing new,’ he said. ‘I confessed to the same thing at your division headquarters. I believe in the government caring for all the people, the poor before the rich. I believe in the state of personal purity that makes this possible. But I finally came to believe that the government these men from the north want to set up can’t be controlled by the very people it’s supposed to serve.’

‘And what do you think of these people you’ve joined to fight with now?’ I said.

He took a last drag on his cigarette and then leaned forward to stub it out in an ashtray at the corner of my desk. He sat back and folded his hands in his lap and his face grew still, his mouth drew down in placid seriousness. ‘I understand them,’ he said. ‘The Americans, too. I learned about their history. What they believe is good.’

I admit that my first impulse at this was to challenge him. He didn’t know anything about the history of Western democracy until after he’d left the communists. They killed his wife and his children and he wanted to get them. But I knew that what he said was also true. He was a believer. I could see his Buddhist upbringing in him. The communists could appeal to that. They couldn’t touch the Catholics, but the Buddhists who didn’t believe in all the mysticism were well prepared for communism. The communists were full of right views, right intentions, right speech, and all that. And Buddha’s second Truth, about the thirst of the passions being the big trap, the communists were real strict about that, real prudes. If a VC got caught by his superiors with a pinup, just a girl in a bathing suit even, he’d be in very deep trouble.

That thing Thập said about personal purity. After it sank in a little bit, it pissed me off. But this is a weakness of my own, I guess, though at times I can’t quite see it as a weakness. I’m not that good a Buddhist. I live in America and things just don’t look the way my mother and my grandmother explained them to me. But Thập suddenly seemed a little too smug. And I wasn’t frightened by him anymore. He was a communist prude and I even had trouble figuring out how he’d brought himself to make a couple of kids. Then, to my shame, I said, ‘You miss being with your wife, do you?’ What I almost said was, ‘Do you miss sleeping with your wife?’ but I wasn’t quite that heartless, even with this smug true believer who until very recently had been a bitter enemy of my country.

Changing my question as I did, even as I spoke it, I thought I would never get the answer to what I really wanted to know. As soon as the words were out of my mouth, I felt a flush spread from under my chin and up my face. It was only a minor attack of shame until I saw what was happening before me. I suppose it was the suddenness of this question, its unexpectedness, that caught him off guard. It’s an old interrogation trick. But Thập’s hands rose gently from his lap and I knew they were remembering her. It all happened in a few seconds and the hands simply lifted up briefly, but I knew without any doubt that his palms, his fingertips, were stunned by the memory of touching her. Then the hands returned to his lap and he said in a low voice, ‘Of course I miss her.’

I asked him no more questions, and after he was gone, my own hands, lying on the desktop, grew restless, rose and then hid in my lap and burned with their own soft memories. I still had a wife and she had not been my wife for long before I’d had to leave her. I knew that Thập was no ghost but a man and he loved his wife and desired her as I loved and desired mine and that was within the bounds of his purity. He was a man, but I wished from then on only to stay far away from him. The infantry guys had their own interpreter and I wouldn’t have to deal with Thập and I was very glad for that.

Less than a week later, however, I saw him again. It was on a Sunday. Early that morning there’d been some contact out in the Long Khánh Mountains just to the east of us. First there was the popping of small arms for a few minutes and then a long roar, the mini-guns on the Cobras as they swooped in, and then there was silence.

In the afternoon the enlisted men played cricket and I sat beneath a tree with my eyes on them but not really following this strange game, just feeling the press of the tree’s shade and listening to the thunk of the ball on the bat and the smatterings of applause, and I let the breeze bring me a vision of my wife wearing her aó dài, the long silk panels fluttering, as if lifted by this very breeze, as if she was nearby, waiting for me. And a few times as I sat there, I thought of Thập. Maybe it was my wife who brought him to me, the link of our yearning hands. But it wasn’t until the evening that I actually saw him.

It was in the officers’ club. Sometimes they had a film to show and this was one of the nights. Captain Townsend got me there early to help him move the wicker chairs around to face the big bed sheet they’d put up at one end for a screen. Townsend wouldn’t tell me what the film was. When I asked him, he just winked and said, ‘You’ll like it, mate,’ and I figured it was another of the Norman Wisdom films. This little man, Wisdom, was forever being knocked down and tormented by a world of people bigger than him. Townsend knew I didn’t like these films, and so I decided that was what the wink was all about.

Thập came in with a couple of the infantry officers and I was sorry to see that their interpreter wasn’t with them. I couldn’t understand why they had him here. I guess they were trying to make him feel welcome, a part of their world. I still think that. They just didn’t understand what sort of man he was. They clapped him on the back and pointed to the screen and the projector, and they tried their own few words of Vietnamese with him and some of that baby talk, the pidgin English that sounded so ridiculous to me, even with English being my second language. I didn’t think Thập would like Norman Wisdom either. Thập and I were both little men.

But when he came in, the thing I was most concerned about was that since I was the only other Vietnamese in the club, Thập would seek me out for help. But he didn’t. He glanced at me once and that was it. The two infantry officers took him up to the front row and sat him between them, and when Thập was settled, my attention shifted enough that I finally realized that something was going on here out of the ordinary. The Aussies were unusually boisterous, poking at one another and laughing, and one of them yelled to Townsend, ‘You intelligence boys have to smuggle this stuff in?’

Townsend laughed and said, ‘It was too bloody hot even for us, mate.’

I didn’t know what he was talking about and I was evidently staring at Captain Townsend with my confusion clear on my face. He looked at me and then put his arm around my shoulders. ‘You’ll see,’ he said. ‘It’s for all us boys who are missing our little ladies.’ He nodded me toward the chairs and I went and sat a couple of rows behind Thập and a little to his left. I could see only the back of his head, the spray of his hair, his deep brown neck, the collar of his plaid shirt. He raised his face to the screen and the lights went out and the films began.

There were nine of them, each lasting about twenty minutes. The first began without any credits. A man was walking along a country path. He was a large, blond-haired man, Swedish I later learned, though at the time it simply struck me that this wasn’t the sort of man who would be in a Norman Wisdom movie. He was dressed in tight blue jeans and a flannel shirt that was unbuttoned, exposing his bare chest. I had never seen an Englishman dressed like that. Or an Australian either. And Wisdom’s movies were all in black and white. This one was in grainy color and the camera was quaking just a little bit and then I realized that all I was hearing were the sounds of the projector clicking away and the men beginning to laugh. There was no soundtrack on this film. Someone shouted something that I didn’t catch, then someone else. I thought at first that there’d been a mistake. This was the wrong film and the men were telling Townsend to stop the show, put on little Norman. But then the camera turned to a young woman standing by a fence with cows in the background and she was wearing shorts that were cut high up into her crotch and she shook her long hair and the Australians whooped. The camera returned to the man and he was clearly agitated and the club filled with cries that I could understand now: Go for her, mate; put it to her, mate; get on with it.

I glanced at Thập and his face was lifted to the screen, but of course he did not know what was about to happen. I looked up, too, and the man and woman were talking with each other and then they kissed. Not for long. The woman pulled back and knelt down before the man and she unsnapped and unzipped his blue jeans and she pulled them down and he still had his underpants on. I discovered, a little to my surprise, that I could not breathe very well and I felt weak in my arms. I had never seen a film like this, though I’d heard things about them. But there was a moment, when the man remained clad in his underpants, that I thought there was still some boundary here, that this was not a true example of the films I’d heard about.

But the woman squeezed at him there, playfully, smiling, like this was wonderful fun for her, and then she stripped off his underpants. His body was ready for her and that was very clear there, right on the screen, and she seemed truly happy about this and she brought her face near to this part of him and I drew in a sudden breath as she did a thing that I had never even asked my wife to do, though seeing it now made me weak with desire for her.

And then I looked at Thập. It was simply a reflex. I still had not put together what was happening in this club and what Thập was and what had happened to him in his life and what he believed. I looked to him and his face was still lifted; he was watching, and I glanced up and the woman’s eyes lifted, too; she looked at the man even as she did this for him, and I returned to Thập and now his face was coming down, very slowly. His head bowed low and it remained bowed and I watched him for as long as I could.

I must admit, to my shame, that it was not very long. I was distracted. I said before, speaking of Thập’s ‘personal purity,’ that an indifference to this notion is a weakness of mine. I have never remarried, and I must admit that it pleases me to look at the pictures in some of the magazines easily available in America. The women are so naked I feel I know them very well and the looks on their faces are usually so pleasant that they seem somehow willing for me to know them this way—me personally. It’s a childish fantasy, I realize, hardly the right intentions, and I suppose someday this little desire will lead to unhappiness. But I am susceptible to that. And on that dark night, in that Australian tent in the province of Phước Tuy, I was filled with desire, and I watched all nine films, desiring my wife—mostly her, I think—but at times, too, briefly desiring one of these long-haired women who took such pleasure in the passing farmer, the sailor on the town, the delivery man, even the elderly and rather small doctor.

Three more times I looked at Thập. The first time, his head was still bowed. The second time, he was, to my surprise, looking at the screen. He was watching as the camera settled on the face of a dark-haired woman who was being made love to in the only way I had ever known to do it, and for a time all we could see was her face, turned a little to the side, jarred again and again, her eyes closed. But on her face was a smile, quiet, full of love, but a little sad, like she knew her man would soon have to leave her. I know I was reading this into her from my own life. She was a Swedish prostitute making a pornographic movie, and the smile was nothing of this sort. It was fake. And I know that it’s the same with all the smiles in the magazines. The smiles of these naked women are the smiles of money, of fame, of a hope to break into movies or buy some cocaine or whatever. But on that night in the Australian tent, Thập and I looked at this woman’s face and I know what I felt and something told me that Thập was feeling that, too. He watched for a long time, his face lifted, his hands, I know, yearning.

He was still watching as I turned my own face back to the screen. There were two more films after that, and I viewed them carefully. But my mind was now on Thập. I knew that a few rows in front of me he was suffering. This man had been my sworn enemy till a week ago. The others in this room had been my friends. But Thập was my countryman in some deeper way. And it had nothing to do with his being Vietnamese, either. I knew what was happening inside him. He was desiring his wife, just as I was desiring mine. Except on that night I thought I would one day be with my wife again, and his was newly dead.

But if that was all of it, I don’t think he would have made this impression on me that does not leave. These films he saw sucked at his desire, brought the feel of his wife to him, made his hands rise before him. He was a man, after all. I watched the films till there were no more and I felt bad for Thập, his wanting a woman, wanting his wife, his being drawn by that very yearning to a vision of her body as ashes now and bits of bone. The third time I looked at him, his head was bowed again and it probably remained bowed. It was bowed still when the lights went on and Captain Townsend was called to the front of the room and was hailed for his show with wild applause and cheers.

And as we all shuffled out of the tent I saw Thập’s face briefly, between his two Australian mates, the two infantry officers who had made him feel like he was really part of the gang. Thập’s face told me how it would all end. His eyes were wildly restless, like he’d been on a sapper mission and a flare had just gone off and he suddenly found himself here in the midst of his enemy.

That night he went to a tent and killed one of the two infantry officers, the one, no doubt, who had insisted on his coming to the club. Then Thập killed himself, a bullet in his brain. It was lucky for Townsend that Thập didn’t understand the cheers at the end or the captain might have been chosen instead of the infantry officer. Thập’s desire for his wife had made him very unhappy. But it alone did not drive him to his final act. That was a result of a history lesson. Thập was a true believer, and that night he felt that he had suddenly understood the democracies he was trying to believe in. He felt that the communists whom he had rightly broken with, who had killed his wife and shown him their own fatal flaw, nevertheless had been right about all the rest of us. The fact that the impurity of the West had touched Thập directly, had made him feel something strongly for his dead wife, had only made things worse. He’d had no choice.

And as for myself, I live my life in the United States of America. I work in a bank. I have my own apartment with my own furniture and I have saved more money than I expect ever to need, if I can keep my job. And there’s no worry about that. It’s a big bank and they like me there. I can talk to the Vietnamese customers, and they think I’m a good worker beyond that. I read the newspapers. I subscribe to several magazines, and in one of them beautiful women smile at me each month. I no longer think of my wife. I go to the movies. I own a VCR and at last I saw the movie ‘Mary Poppins.’ The street I live on is one of four named after Mary Poppins in our neighborhood. This is true. You can look it up on any street map.

The Vietnamese on the Westbank do not like the Vietnamese in Versailles. The ones on the Westbank point out that for the ones in Versailles, freedom only means the freedom to make money. They are cold people, driving people, Northerners. The Southerners say that for them, freedom means the freedom to think, to enjoy life. The Vietnamese in Versailles do not like the Southerners. We are lazy people, to them. Unfocused. Greedy but not capable of working hard together for what we want. They say that they are the ones who understand America and how to succeed here. There are many on the Westbank and in Versailles who are full of hatred.

I say that desire can lead to unhappiness, and so can a strong belief. I can sit for long hours from the late afternoon and into the darkness of night and I do not feel compelled to watch anything or hear anything or do anything. I can think about Thập and I can fold my hands together and at those times there is no hatred at all within me.

MR GREEN

I am a Catholic, the daughter of a Catholic mother and father, and I do not believe in the worship of my ancestors, especially in the form of a parrot. My father’s parents died when he was very young and he became a Catholic in an orphanage run by nuns in Hanoi. My mother’s mother was a Catholic but her father was not and, like many Vietnamese, he was a believer in what Confucius taught about ancestors. I remember him taking me by the hand while my parents and my grandmother were sitting under a banana tree in the yard and he said, ‘Let’s go talk with Mr Green.’ He led me into the house and he touched his lips with his forefinger to tell me that this was a secret. Mr Green was my grandfather’s parrot and I loved talking to him, but we passed Mr Green’s roost in the front room. Mr Green said, ‘Hello, kind sir,’ but we didn’t even answer him.

My grandfather took me to the back of his house, to a room that my mother had said was private, that she had yanked me away from when I once had tried to look. It had a bead curtain at the door and we passed through it and the beads rustled like tall grass. The room was dim, lit by candles, and it smelled of incense, and my grandfather stood me before a little shrine with flowers and a smoking incense bowl and two brass candlesticks and between them a photo of a man in a Chinese mandarin hat. ‘That’s my father,’ he said, nodding toward the photo. ‘He lives here.’ Then he let go of my hand and touched my shoulder. ‘Say a prayer for my father.’ The face in the photo was tilted a little to the side and was smiling faintly, like he’d asked me a question and he was waiting for an answer that he expected to like. I knelt before the shrine as I did at Mass and I said the only prayer I knew by heart, The Lord’s Prayer.

But as I prayed, I was conscious of my grandfather. I even peeked at him as he stepped to the door and parted the beads and looked toward the front of the house. Then he returned and stood beside me and I finished my prayer as I listened to the beads rustling into silence behind us. When I said ‘Amen’ aloud, my grandfather knelt beside me and leaned near and whispered, ‘Your father is doing a terrible thing. If he must be a Catholic, that’s one thing. But he has left the spirits of his ancestors to wander for eternity in loneliness.’ It was hard for me to believe that my father was doing something as terrible as this, but it was harder for me to believe that my grandfather, who was even older than my father, could be wrong.

My grandfather explained about the spirit world, how the souls of our ancestors continue to need love and attention and devotion. Given these things, they will share in our lives and they will bless us and even warn us about disasters in our dreams. But if we neglect the souls of our ancestors, they will become lost and lonely and will wander around in the kingdom of the dead no better off than a warrior killed by his enemy and left unburied in a rice paddy to be eaten by black birds of prey.

When my grandfather told me about the birds plucking out the eyes of the dead and about the possibility of our own ancestors, our own family, suffering just like that if we ignore them, I said, ‘Don’t worry, Grandfather, I will always say prayers for you and make offerings for you, even if I’m a Catholic.’

I thought this would please my grandfather, but he just shook his head sharply, like he was mad at me, and he said, ‘Not possible.’

‘I can,’ I said.

Then he looked at me and I guess he realized that he’d spoken harshly. He tilted his head slightly and smiled a little smile—just like his father in the picture—but what he said wasn’t something to smile about. ‘You are a girl,’ he said. ‘So it’s not possible for you to do it alone. Only a son can oversee the worship of his ancestors.’

I felt a strange thing inside me, a recoiling, like I’d stepped barefoot on a slug, but how can you recoil from your own body? And so I began to cry. My grandfather patted me and kissed me and said it was all right, but it wasn’t all right for me. I wanted to protect my grandfather’s soul, but it wasn’t in my power. I was a girl. We waited together before the shrine and when I’d stopped crying, we went back to the front room and my grandfather bowed to his parrot and said, ‘Hello, kind sir,’ and Mr Green said, ‘Hello, kind sir,’ and even though I loved the parrot, I would not speak to him that day because he was a boy and I wasn’t.

This was in our town, which was on the bank of the Red River just south of Hanoi. We left that town not long after. I was seven years old and I remember hearing my grandfather arguing with my parents. I was sleeping on a mat at the back of our house and I woke up and I heard voices and my grandfather said, ‘Not possible.’ The words chilled me, but then I listened more closely and I knew they were discussing the trip we were about to go on. Everyone was very frightened and excited. There were many families in our little town who were planning to leave. They had even taken the bell out of the church tower to carry with them. We were all Catholics. But Grandfather did not have the concerns of the Catholics. He was concerned about the spirits of his ancestors. This was the place where they were born and died and were buried. He was afraid that they would not make the trip. ‘What then?’ he cried. And later he spoke of the people of the South and how they would hate us, being from the North. ‘What then?’ he said.

Mr Green says that, too. ‘What then?’ he has cried to me a thousand times, ten thousand times, in the past sixteen years. Parrots can live for a hundred years. And though I could not protect my dead grandfather’s soul, I could take care of his parrot. When my grandfather died in Saigon in 1972, he made sure that Mr Green came to me. I was twenty-four then and newly married and I still loved Mr Green. He would sit on my shoulder and take the top of my ear in his beak, a beak that could crush the hardest shell, and he would hold my ear with the greatest gentleness and touch me with his tongue.

I have brought Mr Green with me to the United States of America, and in the long summers here in New Orleans and in the warm springs and falls and even in many days of our mild winters, he sits on my screened-in back porch, near the door, and he speaks in the voice of my grandfather. When he wants to get onto my shoulder and go with me into the community garden, he says, ‘What then?’ And when I first come to him in the morning, he says, ‘Hello, kind sir.’