Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Books on Demand

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

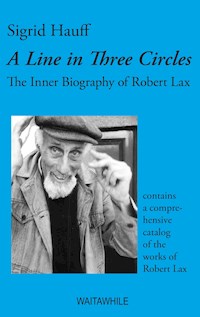

Robert Lax (1915 - 2000) was a close friend of Thomas Merton, Ad Reinhardt, and the beatniks. After his studies at Columbia University, he worked for Time, Parade, and The New Yorker - and then published his first book: Circus of the Sun. As Jubilee´s roving editor he travelled a lot, and finally decided to stay in Greece, where he found the quietness he needed for his poetic work. Living a solitary life on Greek islands, he became one of the great loners of American literature. The process of his mental, spiritual, and artistic development is what makes Lax´s life most interesting. ´The Inner Biography´ stresses on his search for his own way of life, with references to his texts and poems. He made his daily life a ritual, transposing his experiences into his poetry: life has something to do with art, & it´s just a matter of finding the special point at which the two of them get together. His deliberate slowness, his spirituality, his charisma, and his poetic work impressed everybody who met Robert Lax. The book also contains a short biographical synopsis of Lax´s life, and a comprehensive catalog (635 entries) of the works of Robert Lax.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 159

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Thanks to Marcia Kelly for giving permission to quote from the works of Robert Lax.

Contents

Sigrid Hauff

A Line in Three Circles.

The Inner Biography of Robert Lax

I.

Circus.

The Search for the Point

II.

21 Pages.

Portraits of a Moment

III.

Journals.

The Mystic Journey about One’s Own Axis

Sources

Biographical Synopsis

Photography by Hartmut Geerken

Sigrid Hauff – Hartmut Geerken

The Works of Robert Lax

I. Books, Magazines & Miscellaneous

II. Contributions to Books, Magazines, Newspapers, Anthologies, Catalogues & Interviews

III. Films and Videotapes with Robert Lax (Released & Unreleased)

IV. Sound Carriers (Tapes, MC, LP, CD, DAT; Released & Unreleased)

V. Scenarios & Scores

VI. Radio Productions

VII. Performances

VIII. Exhibitions & Installations

IX. On, For & To Robert Lax (In Alphabetical Order)

X. Archives

Sigrid Hauff

A Line in Three Circles

The Inner Biography of Robert Lax

I. Circus

The Search for the Point

Sometimes my friend and I wonder if we are the last people with our melancholy view of things. Both of us get sick when Hemingway says: Life is worth the fightin’ for.1

New York 1940. »The lost generation« that Gertrude Stein had invoked was getting on in years, but had come to terms with this. The young generation, which Robert Lax belonged to in those days, didn’t simply feel lost, it was »beat.« The war raging in Europe was destroying lots of illusions, and the American Way of Life didn’t make it any easier for the young Robert Lax to define his place in the world.

Why – he asked himself – should a young guy like myself walk along up a pretty country road not feeling any but a remembered kinship with trees, creepers, birds, sky and the smell of oil coming up off the cinders? 2

Why should a guy like me, only 25 years old, having gone through normal school and college, having worked some, bummed some, worked more writing letters on a silly job; Why should somebody like me feel completely worthless, looking at his hands, knowing they have no skills for anything except maybe drawing, maybe using the typewriter, things you would do for some small personal satisfaction or because maybe somebody would buy what you drew or wrote, but not because anybody (obviously) every day needed and desired it.3

Robert Lax, nowadays one of the great loners of American literature, set out despite all the adversities in search of something he couldn’t even picture to himself: a life he found meaningful. He jotted down his soliloquies, made his first literary attempts, drew caricatures.

It was the generation after Robert Lax’s – which called itself the »Beat Generation« under quite different circumstances – that first focussed on the trauma of senselessness and worthlessness. Poets like Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac voiced their outspoken protests at the American Way of Life and its conventions.

Protest and resistance – that was nothing for Robert Lax. Born on 30th of November 1915 in Olean, New York State, as the son of Austrian Jews from Kraksw, he was more the reserved and introverted type. He had to solve some pretty vital and fundamental questions – but first of all he had to find a steady job.

In 1934 Lax began reading English literature at Columbia University in New York. Here he often met up and went out with his friend Thomas Merton. Merton, a person full of life, was later to become a monk and priest at a Trappist monastery and bridge-builder between Christianity and Eastern religions.

REMEMBERING

MERTON AND NEW YORK

N. Y. places

I went to

with Merton:

Childs,

103rd

St.

Gold Rail.

West End

Cafeteria

Bar.

A drugstore

(Tilson’s)

on the corner

of 116th &

B’way

»the girl

place«.

The drug

store

on 113th

where we’d

often eat

lunch.

ice-cream

& chocolate

sauce on

toasted

pound

cake,

milk

shakes,

»burn

one«.

Down

town:

The Hickory

House:

Nick’s.

The Famous

Door.

Jimmy

Ryan’s

(52nd St.).

Lowceilinged

place

Count

Basie

played in.

Who played

at Jimmy Ryan’s ?

Teddy

Wilson,

Wingy

Manone,

The Higgin-

bottom

Brothers,

Pee Wee

Russell

(Sunday

afternoon

Jam

Sessions)

good

clarinet

&

bass

with

Teddy

Wilson.

At

Hickory

House:

Joe

Marsala,

Woody

Herman,

Adele

Girard.

Place near

the Taft,

49th St

West?

Where

Hot Lips

Page,

Zutty

Singleton,

Joe Blanton

played &

Billie

Holiday

sang.4

Billie Holiday, the star of the New York jazz scene, sang in the Café Society in Greenwich Village. She was modest, simple, and not yet as glamorously dressed as in later years. Merton and Lax often invited her to a drink at the bar, and would chat in a way that Lax recalls as most agreeable. Billie suggested that Lax should come and visit her in Harlem, where she lived with her mother, and listen to some music. She had a really good record collection. Lax was delighted, but turned down the invite: »being a good student I stuck to my work.«5

Thomas Merton, Ad Reinhardt and Robert Lax became close friends in the thirties, after studying together at Columbia University and working on the editorial staff of the college magazine, Jester. Ad Reinhardt, who was older than Lax, published drawings by Lax and encouraged him to do his own work. Merton, who had yet to find fame or peace of mind, had just converted to Catholicism despite the attempts of Ad Reinhardt – later as famous as a painter as Merton was to become as a writer – to dissuade him. Robert Lax, whom Merton also hoped would become a Catholic, at first followed the advice his mother had given him shortly before her heart attack, and searched for his own roots. He began taking his Jewishness seriously, ate Kosher, grew a beard.

At that point, 1940, Robert Lax wrote a page for the New Yorker that caused a sensation. »A radio masque for my girl coming down from Northampton« – an early Beat scenario:

A RADIO MASQUE FOR MY GIRL COMING DOWN FROM NORTHAMPTON

PART I – AUBADE

Announcer:

Now, like a snail track,

Dawn on the windows

Creeps from the roof

To the eighty-eighth floor.

Second voice:

An Airdale, in the morning gale,

Strolls with a troll near the reservoir.

Deep, interpretive voice:

The city’s supply

Of water is high,

But the reservoirs of life

Are low.

Announcer:

From the truck

To the walk

With a smack,

A pack

Of daily papers

Falls on its back.

Newsboy voices:

War in China!

War in China!

War at least in England, France, and China!

Deep voice (nudgingly):

Yesterday’s papers roll in the gutter,

Yesterday’s scream is a stifled mutter.

Life rolls by with a muffled motor,

Dropping the news with a thwack.

Announcer:

The tongue of the milk horse dangles wearily

The tongues of the faithful lift in ritual

Pontifical:

From her dove-gray lip the church draws in

A black tongue of people, of minds spiritual.

Announcer:

A tongue will convey the Host to the soul

And to the body, viosterol.

Mixed chorus:

Tongues for stamps,

And drop-mouth gaping

Tongues for scrutiny and scraping

Tongues of sick dogs lick the lawn.

And tongues will wag when teeth are gone

Announcer:

From an eastern pane

Of a southbound train,

The tongue of my red-haired girl is plain

Contemptuous of dawn.

Newsboy voices:

War in China!

War in China!

War at least in France and China!

MIDWAY COMMERCIAL

Announcer:

Do you ever wake up feeling awful ? Does the day settle on you like a great straw hat?

Are you edgy and impatient? Do you hate the voices of children? Do you ever say »lf the elevator doesn’t come in two minutes, I’ll kill myself.« Is your husband or wife the last person in the world you want to see? Then what you need is Opium.

Opium, spelled O P I U M, is obtainable from any gray shifty-eyed little man at your nearest corner – not too near the light.

OPIUM corrects the body’s natural habits by turning the usual frenzy of waking into the beautiful serenity of your favorite dream. It conquers, scientifically that awful feeling that comes from too much normal living.

Pipe-smokers, here’s new fun for you! But smokers and non-smokers alike will find that OPIUM gives you two times the comfort at one half the cost. Don’t beat your head with a shoe! Patronize your neighborhood cokey. Get rid of that awful feeling.

PART II – DEVOTIONAL

(Lead-in song:

»My Heart Belongs To Nobodaddy«)

Chorus of the people of Canterbury:

Longtime among us we have told the tale,

From the grayest lips to the tannest ears:

Soon the redeemer will come from

Northampton,

Soon, the tale has said for years.

When will she come, the bright redeemer?

When, discarding the cobbleshoe of humility

Barefoot, over the stubble field

of individual aspiration,

Will she walk laughingly?

Well, when?

(Song: »Grosbeak’s Exception«*)

Other days are gray

Today will be bright;

Other days are dull,

Today will be pretty;

Other days have hair in their eyes,

Today will be clear-faced.

Other days are Monday, Tuesday

Wednesday, Friday, Saturday and Sunday

But today, today will be Thursday

Other days are wet,

Today will be dry;

Other days are cold,

Today will be warm;

Other days say, »Wake up, stupid,«

Today will say, »Good morning, Arthur.«

Other days are Monday, Tuesday,

Wednesday, Friday, Saturday, and Sunday,

But today my girl comes, today will be

Thursday

Chorus:

When will she come,

The bright redeemer?

When walk laughingly over the stubble?

Train chugging:

Cras amet qui numquam amavit:

Quisquam amavit, cras amet.

(It pulls into Grand Central Station.)

Chorus of Redcaps:

Carry your cross, Miss?

Check your effulgence?

Cabbies;

Taxi, there, Miss?

Taxi, there, Miss?

Taxi, taxi, taxi, dear Miss? 6

* This song is named for the famous German scientist John Hampton Grosbeak, who checked over all the calendars in the world and discovered that all the days of the week are named Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Friday. Saturday, or Sunday, except Thursday.

Thomas Merton considered the scenario his friend Lax wrote for his »girl« Nancy Flagg to be the best thing to appear in the New Yorker in 1940.

Unmistakable here is the influence of James Joyce, whom Lax admired and whose Finnegan’s Wake had appeared a year earlier and sparked more controversy than the start of the Second World War. However, the witty, dadaist distance to the depicted scene is typical of Robert Lax.

For all the burning questions about the whys and wherefores of life, there was no alternative for Robert Lax than to find a job. On one occasion he was supposed to draw up an advertising show for Lucky Strike. After he handed in his text, the boss of the agency took him aside and said that although he thought he could write, he felt certain that advertising was the wrong place for him. To Lax’s surprise, he pulled out a roll of dollar bills from his pocket and told him to take the time now to write his own texts.

The money was enough for the summer of 1940, which Lax spent with Thomas Merton, Ed Rice and other pals and girlfriends at his sister’s summer house in the mountains of Olean.

Everyone wrote, walked around barefoot, wore jeans and forgot to shave. Pretty uncustomary for the good, upright neighbours they would sometimes drop in on. Not every mother would have allowed her daughter to accompany them to this house without having second thoughts.

At the end of these intense weeks, Lax worked for radio, in the editorial office of the New Yorker, and at Friendship House, a charity organisation for blacks. He taught English at the University of North Carolina and became film critic for Time magazine, or rather: watched about four films a day. There was little else to do from Monday to Thursday; he tossed paper airplanes out of the window. Only on Friday did he know which film was to be reviewed, and in how many lines.

A look out of the window:

a young man

and a young girl

in grey, and pink

and black

sort down

27th street

like Adam &

Eve from the garden.

an accountant

in blue shirt

and pressed grey pants

looking around

all over the block

perhaps for an

adding machine.

and a sportive girl

in a lavender skirt

walks up the block

with enough strength in

her stride

to make it

to 168th street.

the greyest man

in the greyest hat

with the greyest shirt

and the blackest suit

walks ever-so-despondently

across the road.

and an old man

with legs like stilts

white hair and a distinguished

blue suit,

makes it as well as he

can

up the block.

solid

solid

solid,

a man in a well-fitting suit

crosses the road on an errand

he’s almost persuaded is right

sunlight stands

within the gate

at the chase

manhattan

bank;

gold as all

the gold

inside;

and quicker

to go

its way.7

In 1946 he found a job in the film script department of Samuel Goldwyn Studios in Hollywood. In the evenings he held long telephone conversations with his favourite uncle, Henry Hotchener, who was chairman of the Theosophical Society. Hotchener was his mother’s brother, and the tutor of the young Krishnamurti.

Lax discussed with him the conflict he had in his ambitions to be a poet and to do charity work, and received the advice that no doubt put him on the right path: to say just what he had to say to all who were ready and came properly equipped.

On 1 September 1947 he noted in his Hollywood diary (published 1996) that

He was still absorbing his education. Still, at 31, he was watching, trying to make comparisons between what he saw & what he had read, what he believed must be true & what others seemed to believe. He became a part of the life around him only to a very limited degree. But he watched it; tried to make sense of it at all times. And by trying to make sense he realized he meant that he tried to make comparisons, classical comparisons drawn from history and simple comparisons drawn from the opinions of those around him.

The reasons even for his semi-detachment were hard for him to understand. There was a temperamental reason which seemed to be interior & perhaps habitual. An unwillingness to be attached. Perhaps a simple dislike for the risks inherent in attachment. Perhaps a more positive love of peace which left him unwilling to forgo the pleasures of his habit and to achieve the dubious rewards of those who went out to achieve the specific ends of attachment.8

Waiting. Searching. Lazing about... There was another aspect of this which seemed less noble: his willingness to accept gifts to prolong his periods of unemployment. Along with this was a willingness to leave a job when it seemed vain to him. To wander from a desk when a fair day called to him.9

When Robert Lax went for a job at CBS radio, the application form asked him for his reasons for quitting each of his previous jobs. He felt he shouldn’t hold back the real reasons for quitting from his potential employer, and wrote by one job »spring time« by the next the German word »Frühling« by the next »primavera« and by the last »printemps«.

He did not know if his own way of life had led him into the company of those of his kind, or if his whole generation in the land had (providentially or accidentally) been turned to meditative wanderers. He felt that there was a little truth in both these theories. But he had met few who were as thoroughly committed as himself, as generally reconciled to this way of life. He thought of the ant and the grasshopper and could not but feel that he & most of his friends were grasshoppers except that, like him, most of them seldom even fiddled.10

Like a grasshopper he, together with many of his friends, would change place with no apparent aim. Being out and about was a new, essential way of feeling. Jack Kerouac later described it in On the Road, published in 1957, which became a cult book for a whole generation. Kerouac was a former admirer of Lax, and for Lax Kerouac was a »nomad at the farthest border.« They started up a regular correspondence and during that period met face to face for the first time. Once, when Lax was visiting Kerouac at his mother’s house in Long Island, he noticed that they gave their loving attention to a very friendly cat.

Kerouac’s mother said that the checkout girl at the local supermarket had showed her a basket full of kittens. Mrs. Kerouac picked up a very sick looking kitten. »You won’t want that one«, the girl said. »He’ll only live a day«. And Mrs. Kerouac said, »Well, he’s going to have one very good day«.

On the road ... Robert Lax celebrated Christmas 1948 with the Cristiani Circus in Florida. The circus had been in New York and he had been fascinated and enchanted by the life of the artistes, which was so utterly different with its familiar, clearly ordered little world.

From that moment on the circus exerted a magic draw on him. Although he afterwards taught English again at Connecticut College, the circus had caught his imagination. So naturally he was thrilled when he received an assignment from the New Yorker in summer 1949 to write on the Cristianis, the circus family.

What was it he liked about the circus? The fact that the circus wants to be nothing other than what it is.

I have often thought how much like

a circus the world is, and how

the more like a circus it becomes, the better.

These are some of the reasons:

More than almost anything in the world, the circus is an end in itself.

(That used to be said of all art, but too often literature, painting & music, even ballet turn into means & servants of some other end.)

No one jumps through a hoop on horseback to prove a point (except, incidentally, the point that anything that is done proves i. e. that it can be.)11

The acrobats left a lasting impression on Robert Lax. Their artistry is play, irresponsible play combined with supreme self-control and presence of mind. This and only this is how Robert Lax could picture work – most especially the work of a poet. The immense demands he placed on ›work‹ as art became clear.

Perfection – that’s what seemed truly worthwhile to him.

Like civilizations

and

everything

that grows,

it holds

in

perfection

but a little moment.

The world too is always in motion.

Nothing abides,

all changes.

A bright bubble

turns to the light

and is seen no more.

(For this poor world presenteth

naught but shows

whereon the stars in

secret influence comment)

Everyone who travels with a

circus is of use to the circus.

Nobody is just along for the ride.12

Robert Lax discovered a very pure form of religious devotion in the acrobat’s playful work.

It is not acrobatics on horseback.

It is ballet.

Is is not comic ballet.

It is appropriately dignified praise.

An ancient

and very pure form

of religious devotion.

It is easy to compare it

to the child-like devotion

of the jongleur de Notre Dame;

but it is more mature,

more knowing.

Like the highest art

it is a kind of play

which involves

responsibility