5,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

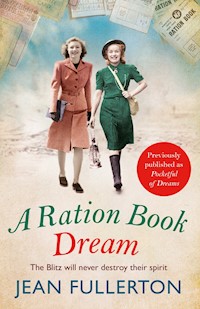

'An enthralling page-turner' DILLY COURT 'A heart-warming WW2 love story' ROSIE GOODWIN 'The queen of East End sagas' ELAINE EVEREST Jean Fullerton, the RNA-shortlisted queen of the East End, returns with the final nostalgic and heart-warming story of the Brogan family. _____ In the final days of war, only love will pull her through . . . Queenie Brogan wasn't always an East End matriarch. Many years ago, before she married Fergus, she was Philomena Dooley, a daughter of Irish Travellers, planning to wed her childhood sweetheart, Patrick Mahone. But when tragedy struck and Patrick's narrow-minded sister, Nora, intervened, the lovers were torn apart. Fate can be cruel, and when Queenie arrives in London she finds that Patrick Mahone is her parish priest, and that the love she had tried to suppress flares again in her heart. But now in the final months of WW2, Queenie discovers Father Mahone is dying and must face losing him forever. Can she finally tell him the secret she has kept for over fifty years or will Nora once again come between them? And if Queenie does decide to finally tell Patrick, could the truth destroy the Brogan family? ___ Praise for Jean Fullerton: 'Charming and full of detail... You will ride emotional highs and lows... Beautifully written' The Lady on A Ration Book Daughter 'A delightful, well researched story' bestselling author Lesley Pearse * What are readers saying about Jean Fullerton? 'I loved it. Easy to read and loveable characters. If you love novels set during WW2 then this is a must read.' 'A must-read story that I'd strongly recommend for readers who enjoy historical family stories.' 'This author never fails to keep you enthralled with each page. Hopefully this isn't the last we see of the Brogans.' THE RATION BOOK SERIES A Ration Book Dream A Ration Book Christmas A Ration Book Childhood A Ration Book Wedding A Ration Book Daughter A Ration Book Christmas Kiss A Ration Book Christmas Broadcast A Ration Book Victory

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Jean Fullerton is the author of seventeen historical novels and two novellas. She is a qualified District and Queen’s nurse who has spent most of her working life in the East End of London, first as a Sister in charge of a team, and then as a District Nurse tutor. She is also a qualified teacher and spent twelve years lecturing on community nursing studies at a London university. She now writes full time.

Find out more at www.jeanfullerton.com

Also by Jean Fullerton

The Ration Book Series

A Ration Book Dream

A Ration Book Christmas

A Ration Book Childhood

A Ration Book Wedding

A Ration Book Daughter

A Ration Book Christmas Kiss

A Ration Book Christmas Broadcast

A Ration Book Victory

Short Stories

A Ration Book Christmas Kiss

A Ration Book Christmas Broadcast

Published in paperback in Great Britain in 2022 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Jean Fullerton, 2022

The moral right of Jean Fullerton to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN: 978 1 83895 094 1E-book ISBN: 978 1 83895 095 8

Printed in Great Britain

CorvusAn imprint of Atlantic Books LtdOrmond House26–27 Boswell StreetLondonWC1N 3JZ

www.corvus-books.co.uk

For all the readers who havefollowed the Brogan family for thepast six years and love them asmuch as I do.

Prologue

Kinsale, Ireland. June 1877

WITH HER FINGERS woven together in prayer and her eyes tight shut, five-year-old Philomena Dooley shifted from one knee to the other to ease the numbness caused by the cold flagstones of the Carmelite Friary Church, which served the good and faithful in the parish of Kinsale.

Although the bright summer sunlight streaming through the church’s stained-glass window dappled the stone floor with a kaleidoscope of colours, inside the whitewashed walls the air was cool. Philomena expected nothing else as, for sure, hadn’t it been the same each and every time she’d ever attended? Even the blessed saints perched on their pedestals between the pillars looked chilly.

Opening one eye, Philomena squinted at her mother kneeling beside her.

Kathleen Dooley, her head bowed low, her eyes closed and the pink rosary that had been blessed by the Pope himself clasped between her hands, had the same dark brown hair and eyes as Philomena herself.

On the other side of her were Philomena’s brothers and sisters, with faces scrubbed and curly hair anchored with Brilliantine and ribbons respectively, knelt in age order with their father Jeremiah Dooley at the end.

As was usual when they attended church, she and her family were dressed in their very best clothes. For her mother this was a high-necked cream blouse with her long black skirt pooling around her, and a paisley shawl draped over her head and shoulders, while her father wore his least-worn trousers, which had been laid under the mattress for three days to be rid of the creases, and a flowery waistcoat under his jacket.

Philomena’s best was a flowery blue cotton dress with long puffy sleeves and a frilly button-up collar. Although her mother had made it from a gown bought from a clothes dealer and it didn’t quite reach to the top of her boots, Philomena knew that any princess in the land would envy her for the wearing of it.

She and her family were sitting at the back. Her mother said it was because they hadn’t been in the parish long enough to have a regular pew, but Philomena knew better.

For hadn’t she seen the sideways looks and heard the word ‘tinkers’ whispered since she was old enough to walk beside the family’s vardo while Major, their piebald horse, pulled it along the dusty highways of Munster and beyond?

And on such a day as this, with God’s beauty dancing all over the meadows and streams, sure wouldn’t she rather be sitting on the running board swinging her legs than stuck in this old bleak building?

‘Ite, missa est,’ said Father Parr, cutting through Philomena’s musing.

‘Deo gratias,’ responded the congregation.

Shuffling themselves into the order of precedence, those in the sanctuary made their way out of the church.

Philomena and the rest of the congregation bowed their heads again for a final prayer then those at the front of the church rose to make their way out.

Philomena’s family, knowing it wasn’t their place to step out in front of their betters, stayed in their seats.

A well-fed farmer with his wife beside him and eight or so children following like ducklings behind started down the aisle towards the door.

They were clearly prosperous because the man’s tweed suit did not bag around the knees and he sported a bowler hat instead of the cap worn by hired men. His wife’s attire, too, showed they had status in the town: she wore a matching dress and jacket plus a black straw bonnet instead of the usual headscarf.

As they made their way down the aisle, the youngest of the three sons, who looked to be just a couple of years older than Philomena, caught her eye. He was dressed in short trousers and a tweed jacket very like his elder brothers. However, whereas their straight hair was neatly parted and anchored down by their father’s pomade, the younger boy’s springy black curls caressed his forehead.

Although her mother would have chided her for staring, Philomena couldn’t take her eyes from him.

As the family drew close, the boy’s blue-grey eyes met Philomena’s dark brown ones.

The odd sensation of distant whispering and murmuring that came upon her from time to time suddenly filled her head.

They stared at each other for a second, or perhaps for ever, then he winked.

Dumbfounded, Philomena felt rooted to the spot as the boy followed his parents.

Her family rose to their feet and automatically Philomena did the same and made her way out of the church into the bright summer sunlight.

Watching a fat bee disappear into the purple bell of a foxglove by the churchyard wall, Philomena turned her face towards the sun.

The Mass had been over for a good while and Philomena’s belly was informing her it was empty, so she guessed it was almost midday, but as it was only a short walk back to the cottage, she was content to sit on the lichen-covered gravestone at the far corner of the burial ground for a while longer.

Across the graveyard the muted sound of the congregation drifted over. Her parents were amongst them. Her mother called it being friendly but, in truth, she only stayed to chat to the other women for her husband’s sake, hoping her neatly scrubbed and cleanly dressed children would indicate they were a good Christian family and that her husband was therefore worthy of employment.

‘You shouldn’t be sitting on that grave.’

Philomena opened her eyes to find the boy who she’d seen in church standing in front of her.

‘Why?’

‘Because it’s where Mother Twomey’s buried,’ he replied.

‘Is she kin of yours, then?’

He shook his head. ‘She was a witch that lived hundreds of years ago.’

‘If she’s a witch, why was she laid to rest in the graveyard?’ said Philomena.

He shrugged. ‘People say if you disturb her, she’ll come back to haunt you.’

‘Well, let her, because I like sitting here.’ Philomena gave him a sideways look. ‘You can sit here, too, if you like. Unless you’re afeared.’

He hesitated for a moment then jumped up on to the slab of stone beside her.

‘What’s your name?’ he asked, shuffling along next to her.

‘Philomena. What’s yours?’

‘Patrick,’ he replied. ‘I saw you in church. Your family have just taken the cottage on the Ballyvrin Road.’

She nodded. ‘Three weeks back.’

Truthfully, what the boy called a cottage most would recognise as a shed. And a leaky one at that. For hadn’t it taken her father a full two weeks to replace the missing slates, while her mother spent days on her knees scrubbing mouse dirt from the pantry and pigeon droppings from the windows.

‘Why have you got a wagon in the garden?’ he asked.

‘That’s what we lived in before coming here,’ Philomena replied. ‘But Mammy told Pa we needed to settle so we can go to school. But I already know my letters. Mammy taught me from our Bible.’

‘Me too,’ he said. ‘When’s your birthday?’

‘August. When’s yours?’

‘September and I’ll be seven,’ he replied.

‘I like your curly hair,’ said Philomena.

He gave her a bashful smile then looked away. He drummed his heels lightly on the stonework a couple of times then his attention returned to Philomena.

‘Shall we be friends?’ he asked.

The world around Philomena suddenly shifted into a new pattern.

‘Yes, for ever, Patrick,’ she replied, certain that her words were no lie.

‘Patrick!’

They both looked around.

Standing next to a monument about ten yards away stood a mousey-haired, flat-faced girl.

‘Pa wants you,’ she shouted.

She looked about the same age as Philomena, was wearing a brown skirt with a matching jacket, and a belligerent expression beneath her bonnet. Whereas Patrick’s eyes were warm and friendly, his sister’s were as cold as the depth of winter.

‘Coming, Nora,’ Patrick shouted back.

Jumping off the grave, he turned to face Philomena.

‘Do you know the split elm on the track from the castle to Cluain Mara?’ he asked in a low voice.

She nodded.

‘Meet me there tomorrow afternoon,’ he said.

‘Patrick!’ his sister yelled again.

Giving Philomena a brief smile, he ran off.

However, before Patrick reached her, Nora opened her mouth a final time. Looking straight at Philomena, and in a voice that was in danger of raising those below from their slumber, she added, ‘And, Patrick, you shouldn’t be bothering yourself with a dirty didicoy.’

Chapter One

‘THANK YOU, QUEENIE,’ said Bernadine O’Toole, taking the half a dozen eggs wrapped in newspaper from her and placing them carefully into a pudding bowl. ‘Would a tin of condensed milk and a pack of Rowntree’s cocoa be all right?’

‘They’d be grand,’ replied Queenie.

Philomena Brogan, the head of the large Brogan family and known as Queenie from Aldgate Pump to Bow Bridge, was standing in Bernadine O’Toole’s kitchen. It was the first Monday in February 1945.

With its lino covering the beaten-earth floor, the large butler sink with its single cold tap and an oven that should have been in a museum, Bernadine’s kitchen was very like Queenie’s own a few streets away in Mafeking Terrace.

Although the bright winter sun was high in the sky, ice had still crunched under Queenie’s feet when she’d walked down Watney Street Market earlier that day. Being the day after payday, the stalls and shops in the market had been full of late-morning shoppers, but Queenie had been up since before dawn. While the day was just a promise in the eastern sky, she had pulled one of her grandson Billy’s old balaclavas over her head, laced up her stout day boots and wrapped herself up in her oversized seaman’s duffel coat, then, as she’d done for the past thirty years, she’d set out on her rounds.

Having returned to the family home with the morning bread, she’d removed the old carpet that she draped over the chicken coop each night to keep her two dozen hens warm and the stray cats out, then let the birds into the enclosed area her son Jeremiah had knocked up with old timbers and chicken wire.

She’d only just put the kettle on and lit the parlour fire when Jeremiah came downstairs yawning.

She’d no sooner put a cup of tea in front of him than her grandsons Billy and Michael, fifteen and fourteen respectively, had crashed into the kitchen, still buttoning school shirts and tying ties. Hearing her daughter-in-law Ida dealing with Victoria, the youngest member of the Brogan tribe, in the room above, Queenie had fed the two boys and packed them off to school before putting the family’s laundry in to soak. Having completed her early-morning chores, she’d left to do her deliveries just as the heavy organ tone heralding the morning God slot, ‘Lift Up Your Hearts’, blasted out of the wireless at five to eight. After visiting the market, she’d arrived at Bernadine’s house just as the flat, throaty sound of London Dock’s midday hooters sounded.

Taking the groceries from Bernadine, Queenie laid them carefully alongside the two newspaper parcels at the bottom of the basket.

‘Now, will you be wanting the same next week if I have them?’ Queenie asked, covering her basket with a tea towel and tucking it down firmly.

‘I surely will,’ said Bernadine. ‘Will you stay for a brew?’

‘I would,’ Queenie replied, ‘but Ida is covering the yard this afternoon as Jeremiah’s got a delivery to Ilford, so she’ll be wanting me to keep an eye on that sweet little darling Victoria.’

A fond smile lifted Bernadine’s weary features. ‘I saw her trotting alongside your Ida last week in the market. Taking it all in, she was. Bright as a button.’

‘And with a mischievous streak that would shame a pixie.’ Queenie rolled her eyes.

‘Well, now, it’s only to be expected that Ida would spoil her last one,’ said Bernadine.

Queenie laid her work-worn hand on her friend’s arm.

‘As a good Christian woman, Bernadine, the saints oblige me to tell you the truth that the spoiling of the child is not to be laid at Ida’s feet.’ A grin spread across her wrinkled face. ‘For sure, if she stood still long enough for me to butter her and eat her, so I would.’

Bernadine laughed. ‘Grandchildren are the sweet balm of old age.’

‘That they are,’ Queenie replied, love squeezing her heart. ‘And not so much of the old, Bernadine O’Toole; for like yourself, I’m just a shade over twenty-one.’

Her friend laughed louder. ‘Are you sure you’ve not time for a cuppa?’

Queenie shook her head. ‘I’ve still a hundred things to do before heading home, but when next I come, I promise,’ she replied, rebuttoning the toggles of her coat. ‘See you at Confession on Friday as usual.’

‘That you will,’ Bernadine answered as she opened the back door. ‘God keep you until then.’

‘And you,’ Queenie replied as she left.

Retracing her steps between the tubs of potatoes and carrots in the yard to the back gate next to the bog, Queenie opened it and peered around the edge into the alleyway that ran along the back of the terraced houses.

Satisfied no one would see her, she stepped across a swirl of dog dirt in her path and marched swiftly to the end of the alleyway, squelching half-frozen rotting vegetation and mud under her boots as she went.

It wasn’t illegal to swap your rations, but if the Food Department at the Town Hall got wind of the fact she was exchanging a few surplus eggs for groceries, they’d be round like a shot.

Reaching Cable Street, Queenie turned left at the bottom of Watney Street, then, waving a greeting to the women rearranging the display of brassieres and corsets in Shelstone’s window as she passed, she walked under the railway arch and back into the market.

‘Afternoon, Queenie.’

She looked around to see Sergeant Bell, the local bobby, strolling over.

Being an old soldier who’d fought for Queen and Empire against the Boers at the end of the last century, Sergeant Wilfred Bell believed in maintaining high standards and consequently his brass buttons always shone and you could see your face in his buffed toecaps. Despite being just short of his sixty-fifth birthday, he still stood ramrod straight and could make a schoolboy’s ears ring with a well-aimed clip.

By rights, of course, Wapping’s long-serving beat officer should have retired years ago and been pulling pints as a landlord in a country pub, but then Hitler invaded Poland.

‘And to you, Sergeant Bell. And praise be for another quiet night,’ Queenie replied, indicating a couple of elderly ARP wardens having a quiet smoke outside the Lord Nelson across from them.

‘For us, perhaps,’ he replied. ‘But I heard one landed on a block of flats in Southwark last night killing fifty people in their beds.’

‘Those V-2s would shame the devil himself for evil,’ said Queenie, crossing herself.

‘I can’t argue with you there,’ he replied. ‘But perhaps now our boys and the Yanks are pushing Adolf ’s mob back in Belgium, the Allies will be knocking on the gates of the Reichstag before too long.’

‘From your lips to God’s ears, Sergeant,’ said Queenie, as images of the four Brogan men in their khaki uniforms flashed across her mind.

He peered into her basket. ‘Out doing a bit of shopping, I see.’

Queenie gave him a wide-eyed look. ‘Sure now, Sergeant, with detective powers such as those, I’m surprised you’ve not been promoted to the CID.’

One of Sergeant Bell’s shaggy grey eyebrows lifted slightly.

‘The war with Hitler might be coming to an end,’ he said, ‘but that don’t mean me and the lads at the station aren’t keeping a sharp lookout for those adding a bit of something to their rations on the black market.’

‘I’ll bear that in mind, Sergeant,’ said Queenie sweetly.

Giving her a last lookover, the officer touched the brim of his helmet and sauntered off.

Repositioning her basket over her arm, Queenie, too, continued on her way.

Watney Street Market, which had sprung up on a bit of waste ground two hundred years before, was the place where those living in the tightly packed streets of Wapping, Stepney and Shadwell did their daily shop. The many stalls sold everything from household bleach and carbolic soap to second-hand clothes and shoes. It was also the place to pick up the latest gossip, as the small groups of women dotted along the cobbled street testified. Chickens still with their innards and feathers dangled above the kosher butcher’s stall, ready to be defeathered and have their innards drawn once purchased, and a hardware stall displayed hammers, saws and screwdrivers plus tin boxes of screws. There were a number of vegetable stalls, too. Well, that’s to say, potatoes, carrots and parsnips mostly, as the string beans, peas in their pods and cauliflowers still had months to go before they would be ready to make their appearance.

Behind the stalls were the shops, including a couple of shoe shops, a chemist, several hairdressers, a fishmonger and a wireless shop, which also sold records to those posh enough to own a radiogram.

Harris the butchers, where the Brogan family were registered for their meat, was amongst them, as was Sainsbury’s and a Home and Colonial grocers. Of course, sadly, thanks to a visit by the Luftwaffe in 1943, the Romanesque-style Christ Church that had been built a hundred years before was now just a burnt-out shell of brick and timber at the north end of the street.

Greeting acquaintances with a nod, Queenie wove her way up the middle of the market towards the place that was almost a second home to the Brogan family: St Breda and St Brendan’s, which sat a few hundred yards further along Commercial Road.

However, as she reached the top of the market a sudden swirl of troubled spirits circled around her. Emptiness engulfed her briefly then the feeling vanished as quickly as it had arrived, leaving a portent of dread in its wake.

Praying to the Virgin and the saints above to keep from harm those she held dear, Queenie turned at the top of the market and looked towards the grey-stoned church. Her heart leapt into her throat.

There, parked in the road with its door open wide, was an ambulance surrounded by a cluster of women.

With her heart pounding and her basket swinging on her arm, Queenie picked up her pace.

‘What in the name of all that’s holy has happened?’ she asked, stopping beside Mrs Dunn.

‘Father Mahon collapsed, God love him,’ the rectory’s housekeeper replied, crossing herself.

Fear gripped Queenie’s heart. ‘Collapsed! How? When?’

‘About twenty minutes ago in the confessional box,’ Mrs Dunn replied. ‘He’d just finished having his ear bent by Peggy O’Flaherty when he staggered out clutching his chest and crashed on to the floor.’

Queenie opened her mouth to speak but the words galloping around in her head refused to form themselves into a coherent sentence.

At that moment, two ambulance men came through the church’s double doors carrying a stretcher between them and all eyes, including Queenie’s, fixed on the supine figure lying on it. Father Mahon.

‘Sweet Mary, mother of God, no,’ Queenie muttered under her breath.

His wrinkled face was the colour of well-kneaded dough, his lips were blue and his eyelids were almost transparent. For a split-second Queenie thought he’d already joined the angels, but then, mercifully, she noticed his chest rising and falling under the blanket.

She crossed herself as they passed and then, without taking her eyes from his face, followed them to the ambulance.

Standing with her knees pressing against the bumper, Queenie watched as the two ambulance men laid the stretcher on to the fixed bench on the right-hand side of the vehicle. One of them strapped the stretcher firmly to the wall while the other placed an oxygen mask over the priest’s face before jumping out of the back and closing one of the ambulance doors.

‘Mind your back, missis.’

Reluctantly, Queenie stepped aside as he pressed the second door firmly closed and turned the handle. Taking a set of keys from his pocket, he hurried around to the front of the vehicle and clambered into the vehicle’s cab.

There was a throaty roar as the driver revved the engine, then, belching out a thick fog of diesel which stung Queenie’s eyes and sent those around her coughing, the ambulance pulled away. With its bell clanging, the white vehicle sped along Commercial Road on the ten-minute journey to the London Hospital.

‘Here we are, kids, Nanny’s house,’ said Mattie McCarthy, née Brogan, to two-year-old Robert sitting on the toddler’s seat of the Silver Cross pram and four-year-old Alicia walking by her side.

‘Will Granny let us gather some eggs?’ asked Alicia, who with brown hair and brown eyes looked like a replica of her mother at the same age.

‘I’m sure she will if you ask nicely,’ said Mattie, manoeuvring the front wheels to avoid a broken paving slab.

‘Bicbics,’ said Robert, his cheeks red and his eyes bright in the chilly air.

Mattie smiled. ‘If I know Gran, she’ll have a biscuit or two for you when you get there.’

She glanced past Robert at one-year-old Ian. Wrapped up like a blue knitted parcel against the cold and having had an eight-ounce bottle before they set off from home, he had nodded off almost as soon as she’d set off to walk to her parents’ house twenty minutes ago.

Waiting until a grey horse and the milk float stacked high with jingling bottles had passed, Mattie pushed her coach-built pram across the road and into Mafeking Terrace.

Situated between Commercial Road and Cable Street, the row of terraced cottages with front doors that opened on to a narrow strip of pavement was very like the dozens of other streets on the Chapman Estate.

When she’d played on the cobbles as a child, all the houses had had brightly painted front doors, whitened steps and lace curtains at the windows. However, after almost six years of unrelenting pounding by the Luftwaffe, half the windows were now boarded up to save another glazier’s bill, many of the doors were held together with odd bits of wood and most of the once-white steps were given just a cursory wipe over each week. Not, of course, her mother’s. Regardless of everything else she did in the day, Ida would be on her knees scrubbing her front step and a half-circle of pavement just beyond first thing every morning come rain or shine.

Recognising where she was, Alicia dashed off.

‘Stay on the pavement,’ Mattie called after her daughter. ‘Don’t burst in and frighten the hens.’

Within a minute or two Alicia had reached her grandparents’ front door but the youngster knew the drill, so she continued on a few steps then disappeared down the narrow alleyway between the houses that led to the rear yard.

Mattie followed, pushing the pram down the alley towards the back gate. Flipping the latch, she wheeled the pram into the backyard.

Like the front of the house, the back had also radically changed since Chamberlain had given his fateful message. Back then, when she and her brothers and sisters were all still living at home, her father Jeremiah had been the local rag-and-bone man, and their backyard had been used as an overspill from his yard under the Chapman Street railway arches. However, when, as part of the scramble to arms, the Government had taken control of the buying and selling of scrap metal, Mattie’s father had had to find another way of supporting his family and so he had set up a removal and delivery company. Now, almost five years later, it was a thriving business with two three-ton Bedford lorries, a Morris van and a diary full of bookings.

Therefore, instead of the backyard being cluttered with old wash tubs and mangles and unrideable bikes, there was now a barrel planted with potatoes alongside a row of old china sinks planted with carrots and onions. However, the most notable change at the back of the family home was her grandmother’s pride and joy: Queenie’s chicken coop straddling the back wall, which made a welcome addition to the whole family’s rations.

Alicia was standing by the wood-and-wire enclosure watching the hens pecking around in the dirt. She looked around as Mattie walked in.

‘You and Robert go into the warm, sweetheart,’ Mattie said, lifting her son from his perch and setting him on his feet. ‘I’ll get Ian out.’

Leaving the chickens, Alicia climbed the two steps to the back door and then, stretching up, let her and her brother into the house. Gently picking up the still-sleeping baby, Mattie followed them into the welcoming warmth of the kitchen, closing the door behind her.

Her mother Ida, accompanied by the soft tones of Workers’ Playtime drifting out of the wireless on the window sill, was scraping potatoes over the sink.

Ida Brogan was just a couple of years shy of fifty and at five foot four could look Mattie pretty much in the eye. With regular applications of light-chestnut Colourtint, she still managed to keep the silver threads at her temple at bay. Although after six children she was nearer a size fourteen than a size ten, thanks to five years of rationing and running around after three-year-old Victoria, her unexpected late surprise, Mattie’s mother was still pretty trim.

Unlike Mattie, who with rich brunette hair and brown eyes favoured her father’s Irish side of the family, Mattie’s mother was English-rose fair and wore her light brown hair in a curly bob just above her collar.

‘Hello, luv,’ she said, cutting a potato in half in the palm of her hand. ‘Cuppa?’

‘I could murder one,’ Mattie replied.

‘Well, you’d better pop him upstairs on the bed first,’ Ida said, indicating the sleeping infant in Mattie’s arms. ‘Or those three are bound to wake him up with their playing.’

‘I think you’re right, Mum,’ laughed Mattie, as the sound of children’s voices drifted in from the parlour.

Leaving her mother lighting the gas under the kettle, Mattie carried Ian through to the family’s main living area.

Alicia was already sitting on the hearth rug next to three-year-old Victoria, while Robert was riffling through the old toy box in the corner.

Although younger than her own daughter, dark-haired and brown-eyed Victoria was, in fact, Mattie’s sister.

‘Play nicely,’ she said, as she strolled past them and into the square hallway at the bottom of the stairs.

After laying the sleeping baby on the blue candlewick cover of her parents’ double bed, she loosened his coat and blanket a little then removed his woolly hat. Flicking the switch to turn on one bar of the electric fire in the grate, Mattie retraced her steps back to the kitchen, arriving just as her mother finished pouring tea into two mugs.

‘There you are,’ said Ida, placing a mug of steaming tea on the kitchen table.

‘Thanks, Mum.’ Mattie tucked her skirt under herself and sat on the nearest kitchen chair.

Like the backyard, her parents’ kitchen had also changed in the past few years. Firstly, the old dresser that had been wedged against the wall had been replaced by a new lemon-coloured Formica one with eye-level glazed doors and a pull-down, easy-clean work surface. Thanks to a high-explosive bomb landing three streets away that had reduced the old, mismatched crockery they’d used for years to shards, the dresser also housed the new dinner and tea sets Mattie’s father had bought his wife for Christmas.

However, although the furniture had changed, the warmth and love that made the room the welcoming hub of the home was still there in abundance.

‘This is a nice surprise,’ said her mother, dropping the potato in the saucepan beside her.

‘I’m taking the kids to the mums’ afternoon at the church, so I thought I’d pop in on my way,’ Mattie explained. ‘Gran not in?’

‘She’s supposed to be.’ Ida glanced at the clock over the back door. ‘She said she’d mind Victoria for a couple of hours this afternoon as your dad’s got a delivery and I said I’d be there at half one to cover the yard.’

‘Don’t worry,’ said Mattie. ‘If she’s not back, I’ll hold the fort until she arrives.’

‘Thanks, luv.’

Mattie frowned. ‘I hope nothing’s happened to her.’

‘Something happened to your gran!’ Ida gave a flat laugh. ‘Not likely. Queenie’s as tough as old boots.’ She dropped another potato into the saucepan then asked, ‘Good morning?’

‘Not bad,’ said Mattie. ‘Harris’s had just got a new delivery, so I managed to nab a couple of pork chops.’

‘Good for you,’ her mother replied, picking up another potato.

Mattie sighed. ‘Of course, it took most of this week’s meat rations, so we’ll have to eat offal until Wednesday, but I want to give Daniel a bit of a treat before he goes back next week.’

Her mother gave her a sympathetic look.

‘Still,’ she continued, ‘I shouldn’t complain. At least being in Intelligence Daniel will be behind the lines, not like Cathy’s Archie or our Charlie.’

Her mother’s face took on a soft look. ‘I’m glad Charlie got leave at Christmas.’

‘Not as glad as Francesca,’ said Mattie, thinking of her brother and her best friend, who was now his wife.

‘Cathy and the kids are coming for Sunday dinner if you all want to join us?’ asked Ida, swirling the knobbly spud around in her palm as she peeled it.

‘Thanks, Mum,’ said Mattie. ‘But as it’s Daniel’s last Sunday at home, I think we’ll spend it together.’

‘As you should,’ her mother replied. ‘And it said on the news this morning that the Americans have got the Germans on the run in the Ardennes, so perhaps we’ll have all the men home by Easter.’

‘I hope so,’ said Mattie, ‘because those V bombs have everyone at the end of their tether.’

‘One landed on the bottling factory in Limehouse yesterday,’ said Ida.

‘I heard,’ said Mattie.

‘Still,’ her mother went on, forcing a bright smile, ‘at least now spring’s on the—’

The back door swung open and Queenie burst in.

‘I thought you’d forgotten— My goodness, Queenie, what’s happened?’ said Ida, seeing her mother-in-law’s face, which was the colour of parchment.

‘It’s Father Mahon,’ the old woman replied. ‘He’s been taken away in an ambulance.’

‘Is he all right, Gran?’ asked Mattie, her mug hovering halfway up to her mouth.

‘Was it a fall?’ asked Ida, dropping another potato in the pot. ‘I thought he was very wobbly on those altar steps last Sunday, didn’t you, Ma—’

‘For the love of God, Ida!’ shouted Queenie, her white hair standing up as she whipped off the balaclava. ‘Will you cease your squawking? He collapsed.’

Mattie’s mother bristled. ‘Pardon me for living,’ she said, wielding the knife with renewed vigour.

Queenie raised her brown eyes to the ceiling. ‘The spirits told me, so they did. Swirling around me like the mist over water, they were foretelling calamity.’

Ida rolled her eyes.

‘A breath away from eternity, he looked, when they carried him out,’ added Queenie.

Mattie stood up and helped her gran out of her coat.

‘Don’t worry, Gran,’ she said, hooking it behind the door. ‘He’s in the best place.’

‘It’s that chest of his, I’m sure,’ muttered Queenie. ‘And haven’t I told him a thousand times to wrap his scarf across him under his coat when he ventures out? For wasn’t his mammy a martyr to her bronchials all her life.’

‘I’m sure all he needs is a couple of days’ rest,’ said Mattie.

‘Mattie’s right, Queenie,’ chipped in Ida. ‘After all, Father Mahon is getting on a bit now.’

Queenie glared at her daughter-in-law. ‘Getting on a bit? Sure, he’s less than a year older than myself.’

Ida raised an eyebrow but thankfully didn’t reply.

The two women glared at each other for a bit then Mattie put an arm around her grandmother’s slender shoulders.

‘I’m sure the doctors will have him back on his feet in a day or two,’ she said, throwing a pointed look at her mother.

‘Are you?’ Queenie looked pleadingly at Mattie.

‘I’m sure of it,’ said Mattie, hoping her gran couldn’t hear the uncertainty in her voice.

Although it was true there was just under a year between her gran and the good father, Queenie could still outpace a woman half her age, whereas the parish’s long-serving priest struggled to climb the pulpit steps each Sunday.

Queenie looked beseechingly at Mattie for a moment then the old woman’s lined face crumpled and she covered her eyes with her hand. ‘Sure, isn’t the devil himself cleaving my brains with an axe?’

‘I tell you what, Gran,’ said Mattie, giving her a little squeeze, ‘why don’t you go and have a lie-down and I’ll bring you a nice cuppa.’

Meekly, Queenie nodded.

‘You’re a darling, so you are,’ she said, patting Mattie’s hand. ‘Not like some.’

Shooting a belligerent look at her daughter-in-law, Queenie shuffled out.

‘Don’t worry, Mum,’ said Mattie, as Ida glanced at the clock again. ‘As Gran’s not feeling quite the ticket I’ll stay and look after Victoria for the afternoon.’

‘Are you sure, luv?’ said Ida, putting the last of the potatoes in the pot.

‘Of course,’ said Mattie. ‘The kids will be as happy playing here as at the mums’ club. You go when you’re finished.’

Placing the pot of potatoes on the back of the stove, Ida wiped her hands on the tea towel.

‘Thanks, luv,’ she said, checking her hair in her husband’s round shaving mirror on the window sill.

Reaching into her handbag on the kitchen table, Ida took out her lipstick and returned to the mirror.

‘Poor old Gran,’ said Mattie.

‘True,’ said Ida, her voice distorted as she ran the colour around her lips. ‘But she does go a bit overboard every time Father Mahon sneezes.’

‘She is very fond of him,’ said Mattie.

‘Aren’t we all?’ said Ida, dropping the lipstick back in her handbag.

‘And they have known each other since they were tots in Ireland, and he’s been so ill this past year with one thing and another,’ Mattie went on. ‘She must wonder each time if he’ll pull through.’

‘Are you sure you don’t mind having Victoria for the afternoon?’ asked Ida.

‘Honestly, it’s no bother,’ Mattie replied. ‘And I can make sure Gran’s all right too.’

‘And stay for tea,’ said Ida, taking her coat from the back of the door and shrugging it on. ‘It’s liver and onions, so it’ll stretch. Now I must go.’

Ida put her head around the parlour door. ‘Mummy’s off, Victoria, so you be a good girl for Mattie while I’m gone. You’re a luv,’ she said over her shoulder to Mattie as she opened the door.

The tinkle of the bell dangling in the cage of Prince Albert, her African Grey parrot, woke Queenie from her light slumber.

Mercifully, the raw pain in her head had all but gone but the grey swirl of foreboding remained.

Satisfied that the blinding headache was truly banished, she opened her eyes and surveyed the room. With a cast-iron fireplace and the window looking on to the street, by rights this should have been Ida’s best room – reserved for high days and holidays. Instead, it was Queenie’s bedroom and had been since her husband, Fergus Brogan, died thirteen years ago.

Truthfully, thanks to Fergus’s drinking and gambling, she’d had little more than the clothes on her back, a few keepsakes from her Irish home and Prince Albert when she’d arrived at Mafeking Terrace but, loving son that he was, Jeremiah had made sure there was always a fire in the grate when it was needed and over the years he’d furnished the room with her comfort in mind.

The brass bedstead she was lying on had been a fortuitous early find when Jeremiah had been a totter with a horse and cart. As had the dark oak double wardrobe and matching chest of drawers he’d picked up on his rounds. He’d even found her a washstand with a china bowl and jug, so she didn’t have to use the kitchen sink like the rest of the family.

She watched the bird worrying at the chain for a moment then there was a light knock at the door. It opened slightly and Mattie’s head appeared around the edge.

Blessed as she was with such a number of grandchildren, she could honestly say she didn’t have a favourite. That said, the sight of Mattie, with the dark hair and eyes of Queenie’s long-dead mother, always squeezed at her heart. The only wonder of it was that with Dooley blood running through her veins, Mattie didn’t hear the call of the spirit world too.

‘Are you ready for that cuppa?’ Mattie said, giving Queenie a warm smile.

‘That would be grand,’ she replied.

Mattie stepped into the room. ‘I thought I’d join you,’ she said, setting two mugs of tea on the bedside cabinet. ‘Are you feeling better?’

Queenie nodded. ‘I rubbed a little of last Easter’s holy water on my forehead and that seems to have sent my headache packing.’

‘I’m pleased to hear that,’ said Mattie. ‘It’s not like you to have a headache.’

‘Ah, well, they only strike when the spirits are raging,’ Queenie replied.

She shuffled up the bed, resting her back against the headboard, and Mattie adjusted the pillows behind her before handing her grandmother her tea then perching on the foot of the bed.

‘Goodness,’ she said, glancing around the room. ‘I’d forgotten all the little bits and pieces you have.’

‘Well, as your mother was kind enough to point out, I’ve been around a while,’ Queenie replied.

‘Don’t take any notice of Mum,’ said Mattie.

‘Rest easy on that score, me darling,’ Queenie replied, ‘for I never do.’

Taking a sip of her tea, Mattie stood up and went over to the sideboard delicately etched with lilies and rushes that Jeremiah had acquired for Queenie just after she’d moved in.

‘This is your mum and dad, isn’t it?’ asked Mattie, picking up the sepia photo set in pride of place amongst the half a dozen photos Queenie had brought over with her from Ireland.

‘It is,’ said Queenie. ‘Pa had just had the domed roof of our vardo repaired and the body repainted.’

Mattie held the picture closer. ‘Your dad looks very spruce in his striped waistcoat and hat set at a jaunty angle.’

‘Well, there was none such in Kinsale, so Pa had to fetch the photographer from Carrigaline to make the picture,’ said Queenie. ‘Mammy and me spent all morning threading ribbons into Major’s mane, too, so he could put on a show between the wagon’s shafts. Of course, my parents had given up travelling the open road years before and were settled in Kinsale, but Pa felt the urge to wander sometimes so he’d still visit the odd market or fair when the mood took him. He was a Jeremiah, too, as was his pa, and the boy next to him is . . .’ She reeled off the names of her brothers and sisters. ‘And Mammy is holding baby Margaret.’

‘Your mammy looks like Jo,’ said Mattie.

Reaching across, Queenie picked up her tea. ‘And your darling self, too.’

‘Which one is you, Gran?’

‘I’m the girl standing next to Mammy.’ Queenie took a sip of tea. ‘I was about thirteen at the time.’

Mattie replaced the photo and glanced over at a couple of the others, including Jeremiah and Ida’s wedding photo, a studio portrait of Mattie’s brother Charlie in his army uniform along with ones of Mattie and her two sisters in their ARP, Ambulance and WVS uniforms respectively. There was last year’s school photo of Queenie’s youngest grandsons Billy and Michael next to the most recent family photo of Victoria in the christening robe her father had worn almost half a century before.

Then she spotted a photo at the back and picked it up.

‘Is this you at school?’ she asked.

‘No, it was taken at the church picnic.’

Mattie’s eyes ran over it for a minute then she looked around.

‘Is that Father Mahon standing at the end of the back row,’ she asked, looking across at Queenie with wide-eyed astonishment.

Queenie took another sip of tea. ‘That it is.’

‘Goodness, I hardly recognised him with hair. And so much of it, too,’ said Mattie, studying the image. She scanned the photo again. ‘And you’re standing next to him.’

‘Aye, I am,’ Queenie replied.

‘He looks so different. Very handsome, in fact,’ Mattie added. ‘And who’s that standing on the other side of him?’

‘Nora,’ Queenie replied flatly. ‘His sister.’

‘You all look so young,’ said Mattie, still studying the photo. ‘When was it taken?’

‘I can’t quite recall,’ Queenie replied, focusing on the rim of the mug.

‘Mum! Robert’s made Toria cry.’

Mattie rolled her eyes. ‘I thought it was too good to last. I’d better go and see what Alicia wants.’

She returned the photo to its place on the sideboard and, taking her tea with her, left the room.

Queenie placed her own cup on the bedside cabinet beside the alarm clock. Swinging her legs off the bed, and slipping her feet into her slippers, she stood up. Padding across to the sideboard she picked up the photo in the silver frame that Mattie had just been looking at.

Her eyes fixed to the faded image, Queenie smiled.

Yes. Patrick Mahon had been handsome. Very handsome indeed.

Although she’d said otherwise to her granddaughter, Queenie remembered exactly when the photo was taken. It was the summer that she’d turned fifteen.

She remembered the day as if it were yesterday.

The sun was high in the sky and as bright as the future. Until one person destroyed her happiness for ever.

Kinsale, Ireland. April 1880

‘QUICK,’ SAID PHILOMENA, gripping Patrick’s hand as she dragged him around the corner of her parents’ cottage. ‘For in truth this weather’s fit to baptise you.’

‘Are you sure your pappy won’t mind, Philomena?’ he asked, as they splashed through the deepening puddles on the pathway through her mother’s vegetable garden.

Sending rain flying from the tip of her nose, Philomena shook her head. ‘He won’t be taking our wagon on the road until the hiring fairs start in a month or so.’

As always on a day when there were no chores waiting at home for either of them, she and Patrick would wander through the meadows and wood together.

Although it was a warm Thursday afternoon and a few days before April gave way to May, the wind from the south-west had been blowing soft weather their way for the best part of the last week. So as the hollows and dells where they usually lingered in the hope of glimpsing rabbits feasting on the lush spring grass or a red squirrel scampering about in the branches were more like lakes, she decided they’d have to find somewhere drier to shelter.

Diving around the back of the beanpoles, Philomena picked up speed towards the domed wagon, with its carved wooden shafts tilted back, parked at the side of the family dwelling.

Like the hundreds of other vardos carrying families as they roamed the highways and byways, scratching out a meagre living in the villages and towns of Ireland, the Dooley family wagon was about ten feet long and comprised of a domed frame covered by a grey-green tarpaulin hammered into place at the sides. Black rough-hewn planks enclosed the back but the red-painted wooden boards covering the front were set back a couple of feet and gave way halfway across to a canvas curtain that served as a door.

With her bare feet leaving muddy footprints on the handful of steps up to the van’s entrance, Philomena shoved the curtain aside and they fell into the vardo’s warm, dark interior.

Collapsing in a heap, they lay on their backs laughing for a moment, then, catching her breath, Philomena turned her head to look at Patrick.

He lay with his hands on his rising chest, his eyes closed and rainwater dripping from his black curls.

In the dim interior of the wagon, with the rain pitter-pattering on the canvas roof, Philomena’s gaze travelled over his curly black hair, skimmed along his forehead then down to his nose, which now he was almost to the end of his tenth year had lost some of its roundness.

He opened his eyes.

‘I’ve never been in one of these before,’ he said, gazing around at the narrow planks running lengthwise that the tarpaulin roof was nailed to. He sat up. ‘Don’t you have a stove?’

‘Too dangerous,’ Philomena replied, leaning back against the cupboard. ‘Once we were pitched Pa would make a circle of stones outside then set up the tripod and pot over it. Mammy hung all her pots from the ceiling.’ She pointed at the empty hook above. ‘And kept all our crockery in here.’ She banged the empty locker she was resting against with her hand.

He looked puzzled. ‘Didn’t they fall out and smash as the wagon moved.’

Philomena shook her head. ‘They were enamel. Mammy and Pa slept up there.’ She pointed at the raised platform at the end of the carriage. ‘And we bedded down here.’ She patted the floor beneath them. ‘Of course, there was only me, Micky, Breda and baby Cora then. It was when she arrived that me mammy told Pa we should settle somewhere.’

‘What’s in here?’ asked Patrick, pulling open one of the doors beneath the raised bed area.

‘That’s where Pa kept his knife grinder and tools,’ she replied.

‘What’s that?’ he asked, as he peered into the dark empty space.

Philomena rolled over on to her knees and, scrambling forward, followed his eyeline. ‘That belonged to Granny Doodoo,’ she said.

Reaching in, Philomena pulled out an old biscuit tin in the shape of Dublin Castle. There were splodges of rust all over it but the grey enamel paint of the battlements and the green of the ivy were still visible.

‘This van was hers and Grampa Dooley’s,’ Philomena explained. ‘They were Pa’s parents. I don’t remember Grandpa as he died when I was a baby, but Granny Doodoo lived with us, too, until she joined Grandpa in heaven just after Breda was born.’

Patrick pulled a face. ‘Wasn’t that a bit of a jam?’

Philomena shrugged. ‘I suppose, but we were never cold in the winter.’

Sitting cross-legged, Philomena dug her nail under the lid and popped the tin open, releasing a faint musky odour.

‘Is that a pack of playing cards?’ asked Patrick, copying her posture.

‘Yes.’ Reaching in, Philomena pulled out the dog-eared cards. ‘Granny Doodoo used to get them out sometimes.’

Patrick studied them. ‘They don’t look like normal playing cards.’

‘No, they’re what she used to tell people what’s going to happen,’ Philomena replied, studying the colourful images of a sun, a wheel, a tower and a man dangling by his leg upside down.

‘How?’ he asked, his eyes fixed on the one with a skeleton gripping a scythe.

‘I’m not sure,’ said Philomena, gathering them up. She tapped them into order then handed them to Patrick. ‘Gran used to get people to shuffle them . . .’

Awkwardly, Patrick divided the shabby cards in his hands and then forced them back together.

‘And then she’d lay them out like this.’ Philomena placed the cards in a row on the floor between the two of them. ‘She studied them for a while and then . . .’

She lowered her gaze but as her eyes skimmed over the painted images the cloying heat in the van vanished and an icy shudder slithered down her spine.

Her eyes came to rest on the image of a naked man and woman with what appeared to be an angel with its wings outspread hovering above them. A soft whispering coiled in her ears as she stared unblinkingly at the card while images of another place with no fields, brick houses and children with unfamiliar smiles and dimples flooded her heart.

‘Philomena!’

She looked up to find Patrick kneeling on the cards and gripping her upper arms.

‘Thank all the mercies,’ he said, the fearful expression on his face giving way to a look of relief.

‘What happened, Mena?’ he asked.

‘I’m not sure,’ she replied, trying to make sense of the jumble in her mind. ‘But I know somehow they are telling us that we’ll still be together even when we’re really old with white hair.’

Patrick frowned and started gathering up the cards.

‘Isn’t Father Parr forever telling us that the devil is always lurking to steal the souls of those who seek to know the future?’ he said, throwing the cards into the tin and snapping shut the lid.

They sat awkwardly for a moment then Patrick looked up at the roof. Smiling, his eyes returned to her. ‘Sounds as if the rain has passed over.’

Jumping to his feet, he strode to the vardo’s entrance then turned and grinned.

‘Race you to the top field,’ he said, pulling back the canvas curtain and disappearing.

Philomena stood up and followed him out.

Patrick had already reached the front gate when she emerged, but instead of rushing after him, she stood on the front board of her family’s wagon.

A smile lifted her lips.

Patrick might mark her as conjuring a fanciful story, but Philomena knew it was the spirits of the old times whispering in her ear not the devil. And glad she was, too, for didn’t Granny Doodoo’s shabby cards tell her for sure that she and Patrick would grow old together.

Chapter Two

AS FATHER TIMOTHY, St Breda and St Brendan’s assistant priest, turned to face the congregation, Jo Sweete, the second-youngest of the Brogan girls, bowed her head.

It was just after eleven thirty on the second Sunday in February and as usual she was at Mass in her family’s church.

Well, truthfully, as she’d first been carried into church as a two-week-old baby by her mother Ida, the mock-medieval church was more like her second home than a place of reverent worship.

Although the church’s interior still retained some of its original fixtures and fittings, such as the carved oak altar rail, the three-foot-high statue of the Virgin in her white gown was still being safely stored in the crypt along with the statue of St Peter. As the frequency and intensity of the Luftwaffe’s nightly visits had petered out during the previous summer there had been talk of putting them back in the church, but the V-1 rockets falling out of the sky put paid to that idea. The high-explosive bombs had also caused the gummed paper on the stained glass to be renewed and a fresh set of sandbags to be piled around the stone cross at the front of the church.

Members of the congregation stood ready to face this new menace from the sky, so at any church service there was always a sprinkling of black ARP helmets, navy ambulance jackets and green WVS coats, plus the khaki of the Home Guard, with the odd buff-brown boilersuit of the Heavy Rescue thrown in.

Jo had been christened at two months old, taken her first communion at seven and married her childhood sweetheart Tommy here almost three years ago. And although the saints were crated up in the crypt and there was an emergency first-aid station set up in the porch, St Breda and St Brendan’s would always have a special place in Jo’s life and heart.

‘Benedícat vos omnípotens Deus Pater, et Filius, et Spíritus Sanctus,’ said Father Timothy.

‘Amen,’ chorused the congregation.

‘Ite, missa est,’ said the priest.

‘Deo gratias,’ muttered Jo, shivering. She had arrived late so, instead of sitting alongside her family in their usual place, she was freezing her rear off in the back pew near the main doors. Crossing herself, she and the rest of the congregation slid back onto the pews as the priest began to speak again.

‘The notices for this week,’ he said, scanning his clear blue eyes over the assembled worshippers. ‘Monday . . .’ He ran through the usual days and times of services along with the weekly church social clubs. ‘. . . and lastly, I know you are all anxious to know how Father Mahon is progressing,’ Father Timothy concluded.

The congregation nodded.

‘Well, I visited him yesterday afternoon and the doctors say he is stable and in good spirits. However, they also say that it would be wise for Father Mahon to remain in hospital for another week or so, just to make sure he is fully recovered. Father Mahon also wanted me to tell you how much he has valued your prayers and hopes to be back with us in time for Lent.’

There was a collective sigh of relief.

The priest smiled again. He turned and then, preceded by the altar boys and with the choir bringing up the rear, he headed to the vestry.

Bowing her head again, Jo said a quick prayer for Tommy and her family then a very personal one to the Mother of God, a prayer she’d said each day for the past two and a half years, although it had yet to be answered.

She remained still for a moment, then, collecting herself, she opened her eyes, crossed herself again and stood up.

People were already making their way to the doors behind her to leave while others, her family included, were heading for the side door to have a cup of tea in the adjacent hall.

Waiting until there was a gap in the crowd of people filing out, Jo stepped out from the pew.

Genuflecting at the brass cross gleaming in the wintry sunlight that streamed through the window on to the altar, Jo made her way to the side exit.

The small hall that sat behind the church had been built at the turn of the century and had the Edwardian green wall tiles combined with cream emulsion decor distinctive of that genteel era. The oblong windows had been covered with wire mesh in order to stop brick or bottle from shattering the glass and, like the church itself, had been further decorated with gummed tape. Jo had attended Sunday school here as a child, as well as Boys and Girls Saturday Club and the Brownies. However, as the large main hall of the Catholic Club, situated around the corner, had been turned into a WVS rest centre at the start of the war, the children of the church now had to share their space with the pensioners’ lunch club and St Breda and St Brendan’s Catholic Mothers’ League.

Through the crowd of men and women already sitting at the dozen or so square tables enjoying their after-service cuppa, Jo spotted her two sisters: Mattie, holding baby Ian in her arms, and Cathy with her youngest, two-year-old Rory, perched on her lap.

Well, her knee truthfully, as just a week or two away from having to summon the midwife, her sister’s lap had all but disappeared.

Jo’s gaze shifted down to her sister’s swollen stomach and the ache lurking in her chest made its presence known once more. Damping it down, she turned and joined the tea queue.

Having said a quick hello to Ida, who was filling cups from one of the church’s large aluminium teapots, Jo took her cup and weaved her way between the tables to where her sisters were sitting at the back of the hall.

‘Hello, Jo,’ said Cathy, smiling at her as she reached the table. ‘I didn’t think you were here this morning.’

Unlike Jo and Mattie, who with their dark chestnut hair and brown eyes were two peas in a pod, Cathy, with light brown hair and hazel eyes, favoured their mother.

‘I was late, so I slipped in at the back,’ Jo replied.

‘Did you oversleep?’ asked Mattie, taking a sip from her tea.

Jo shook her head.

‘Tommy called.’ She grinned. ‘He’s being posted back to take charge of the army’s signals branch at Northolt, so he’s coming home on Friday.’

‘That’s wonderful,’ said Mattie.

Jo’s grin widened. ‘I think so.’

Tucking her skirt under her, Jo sat on the chair between her sisters.