2,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

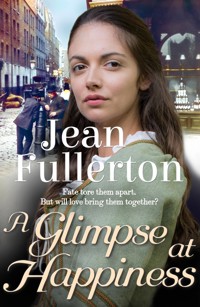

The 1st novel in the East End Nolan Family series. The most talented voice since Dilly Court - an absorbing, thrilling and romantic historical saga with characters you'll fall in love with. Ellen O'Casey, an Irish Catholic immigrant, is struggling to support her ailing mother, her teenage daughter and herself. Washing other people's laundry in the day, and singing in bawdy pubs at night, Ellen is determined to make a better life for her family by saving enough for the passage to New York where the rest of her extended family have already emigrated. But Danny Donovan, a local gangster and the landlord of the pubs where Ellen sings, intends to make her his mistress. A widow in her late 20s, Ellen has refused to let another man in her life, least of all the brutish Danny, whose advances she doggedly resists. But when Ellen catches the eye of the new doctor in town, Robert Munroe, an intense rivalry is formed between the doctor and Danny. For not only are Robert's feelings for Ellen reciprocated, but the ambitious doctor also intends to investigate the appalling living conditions of the local community and Danny's own hand in it. But as Ellen and Robert become closer and aim to bring an end to Danny's reign of terror, their own chance at happiness seems suddenly to be at stake... A sweeping historical romance perfect for fans of Bridgerton

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

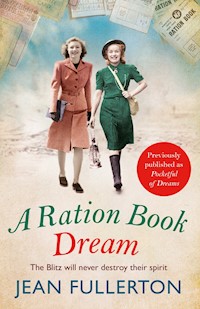

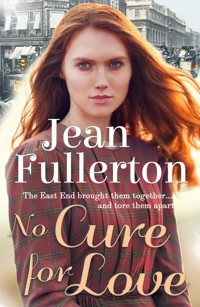

No Cure for Love

Also by Jean Fullerton

No Cure for Love

A Glimpse at Happiness

Perhaps Tomorrow

Hold on to Hope

No Cure for Love

Jean Fullerton

First published in Great Britain in 2008by Orion, an imprint of Hachette UK Ltd.

This edition published in 2018 by Corvus,an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Copyright © Jean Fullerton 2008

The moral right of Jean Fullerton to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

All the characters in this book are fictitious, and any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

A CIP catalogue record for this bookis available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 178 649 5785

CorvusAn imprint of Atlantic Books LtdOrmond House26–27 Boswell StreetLondonWC1N 3JZ

www.corvus-books.co.uk

To Kelvin, my dear husband, for all his love andunwavering support.

One

On an April evening in 1832, with her shawl wrapped tightly over her abundant auburn hair, Ellen O’Casey ducked out of the cold on the Whitechapel Road in East London, and into the tradesman’s entrance of the Angel and Crown.

Thank goodness she had bought a half-hundredweight of coal from the merchant. Even now, in March, The two rooms in Anthony Street she shared with her mother and her daughter, Josie, could be cold, and her mother was still low from the last bout of chest ague.

Through the door that led to the public bar and supper rooms Ellen could hear the familiar buzz of customers enjoying their evening meal. She was late, but the staff area at the back of the public house was deserted and she hoped that she could get to the minute dressing room that she shared with Kitty Henry without being noticed.

Dashing down the narrow corridor, Ellen had almost reached the door with the faded brown paint when someone caught her arm.

‘You’re late,’ the voice of Danny Donovan, owner of the Angel and Crown, snarled in her ear. ‘Kitty has already sent word she is sick.’

Trying not to show the pain from the dirty nails digging into her, Ellen turned and faced the huge Irishman beside her.

‘Josephine was sick. I couldn’t leave her until me Mammy came back,’ she said, trying to free herself. Danny held her fast.

‘I don’t pay you to look after your brat. I pay you to sing.’

Danny Donovan was dressed in his usual flamboyant manner. He wore a mustard frock coat over a multicoloured silk waistcoat, and a thick gold chain was strung across his paunch. A shiver of disdain ran down Ellen’s spine as he glanced over her, and she wrenched her arm away. ‘Then, if you’ll be unhanding me, I’ll go and do just that,’ she said.

He blocked her path. ‘You look well tonight, Ellen,’ he said.

Her outer shawl had fallen away and Danny’s eyes ran momentarily over the simple cotton dress she wore. It suited her more than the satins and feathers the other girls in the Angel wore. It set her apart and Ellen wanted to keep it that way.

Danny snatched the chewed cigar from his mouth, shot his arm around her waist and pulled her violently against him.

‘Come and warm me bed and you won’t have to sing for your supper,’ he said, his large hand making free with one of her breasts. His rancid breath and his body odour of sweat and tobacco hit her in the face and her stomach lurched. ‘I’ll give you money to look after that old mother of yours, and young Josephine. What do you say?’

Using all her might Ellen pushed him away. ‘The same thing I said last time you asked. No,’ she spat, gathering her shawl from the floor and dashing past him to her dressing room.

‘You can play the respectable widow all you like, Ellen O’Casey, but I’ll have you in the end,’ he called after her as she slammed the door.

Ellen leaned with her back to the door in an effort to still her wildly beating heart. She shut her eyes and took measured breaths as panic threatened to engulf her. Every part of her wanted to flee from the Angel and Crown, never to return, but she couldn’t. She needed the money. She had worked here a little over a year and Danny had been after her from the moment she had arrived. He would force her if he ever got the chance, but she was determined never to give him that chance.

‘Come on, Ellen, it won’t be for much longer,’ she told herself firmly as her breathing began to slow.

Three months, four months at most, then she would have the money to buy passages for her mother, Josie and herself to New York to join her brother and his family. With trembling hands, Ellen hung the shawl on the nail behind the door and started to get ready.

Looking in the cracked mirror behind the small dressing table, she contemplated her reflection. She pulled a small curl down and over her shoulder. Her hands slid down to her waist. It had been a gruelling ten years since Michael had died, leaving her with a small child to support, but to look at her, none would have known that she was just shy of twenty-eight and mother to a leggy thirteen-year-old.

Ellen frowned. Her breasts were too visible over the narrow lace of her neckline, and she tugged it up. She didn’t want any of the men in the audience to get ideas.

There was a faint rap on the door. Ellen turned from the mirror and went out. Tommy was standing by the curtain rope when she took her place at the side of the stage. Adjusting the lace around her neckline again, she asked, ‘What’s the house like, Tom?’

‘A bit busier than the usual Friday night.’ Tommy wiped his nose with the back of his hand. ‘Your fame must be spreading.’

The low hum of the supper room reached Ellen’s ears. For a Friday it was quite lively, and she would be fortunate if she got away before midnight.

Peering through the little peephole in the curtain, she glanced across the heads of the diners in the cheap seats in front of the stage, her eyes rested on the raised gallery where the wealthier patrons of the Angel’s supper room sat and ate. Danny Donovan was now lounging in his usual place in the corner against the oak handrail that separated the rooms. He was entertaining loudly.

Ellen caught the conductor’s eye. He winked in acknowledgement over his half-rimmed spectacles and called the small group of musicians to order. The opening bars of ‘In Ireland’s Fair Hills’ drifted across the room and the rumble of conversation stopped.

Tommy pulled energetically on the winding rope and the velvet curtains swished back releasing dust particles into the footlights at the edge of the small wooden stage. With a deep intake of breath, Ellen fixed a smile on her face and stepped out on to the stage.

Doctor Robert Munroe sat alone under the hanging oil lamp that illuminated the main medical laboratory in the London Hospital. For the third time he began reading the letter in his hand. It was from Miss Caroline Sinclair, daughter of Henry Sinclair, owner of Edinburgh’s most successful brewery company, and the young woman with whom – or so his mother insisted on telling her circle of friends – he had an understanding. As he slid the pages under each other, Robert’s lips formed a grim line. Understanding! After reading the contents of the letter through yet again, he reflected that misunderstanding might describe their relationship better.

After a cursory enquiry about his health, Caroline’s letter contained a full page of complaints as to why he was staying so long in London, and demanded that he return to Edinburgh before the Spring Ball and the assemblies which began in May. It finished by telling him about the new captain of the town garrison who was accompanying her family to the opera next week.

Robert raked his hand through his mop of light-brown hair and let out an oath. Why couldn’t Caroline appreciate that in order to continue his studies and make his professional name he had to be in London? He had told her all this when he had left not three months ago.

He let the letter fall from his hands onto the bench and looked up at the laboratory shelves, stocked with various jars containing twisted body parts immersed in jaundice fluid.

I’m supposed to be documenting the day’s findings, not reading Caroline’s letter, Robert thought, firmly putting aside a mental picture of Edinburgh’s foremost beauty standing up beside a heroic, red-coated captain for a country reel.

The smoke from the lamps was beginning to sting his eyes. After all, he had been in the laboratory these past three hours studying the various specimens from the Black Ditch, the foul trickle of what was once a free-flowing stream that passed through much of East London.

He pinched the inside corners of his eyes with his finger and thumb and resumed peering into his newly acquired brass microscope. A few seconds later his attention was broken again as the door creaked open. He looked up to see William Chafford, his friend and colleague enter the laboratory. William was a would-be surgeon, and the son of Henry Chafford, physician to the rich and indolent in Bath and the surrounding county.

‘There you are, old man. What keeps you so late?’ William asked, closing the door sharply behind him and making the glass rattle. The draft from the door disturbed the various waxed dissection charts that hung around the walls.

‘I’m just finishing recording my day’s findings,’ Robert answered, trying to slide Caroline’s letter into his waistcoat pocket without his friend seeing it. But William was too quick.

‘Findings, be blowed,’ he said with a wink. ‘You’ve been sitting here daydreaming over that love letter from your long-suffering fiancée in Scotland.’

‘Miss Sinclair is not yet my fiancée. Although my mother’s every letter presses me to make her so,’ Robert answered. Then he relaxed his stance and pulled the folded paper out of his pocket. ‘I did happen to glance at her letter, but I certainly would not describe this,’ he held the paper aloft, ‘as a love letter.’

William gave him a sympathetic look. ‘Munroe, you must find yourself some better company than these dull fellows,’ he said, sweeping his hand around to include the petrified specimens stored in the coloured glass bottles.

‘Take a look at these, Chafford,’ Robert said, indicating the microscope.

With one eye closed, William peeked down at the worm-like entities as they squirmed and multiplied in the droplet of water.

‘Ugh. Where did you get these nasty-looking brutes, Rob?’ he said, pulling a face. Robert’s usually sober expression changed to an open smile.

‘From the Black Ditch this morning,’ he replied. ‘And if you ingest enough of them they’ll make your bowels turn to water. No wonder sickness is rife amongst the poor souls who live in the dark alleys of Wapping.’

‘Gad, whatever gives you that idea? You can’t even see them without the ’scope.’ William straightened up, pulled down the front of his silk waistcoat and adjusted his cravat. ‘I can’t understand why you are so fascinated with the water worms,’ he continued, as he strolled past the grinning, bleached skeleton that hung patiently awaiting the next day’s lecture.

Robert let out a rumbling laugh. ‘That’s why I’ll be the chief physician in Edinburgh while you’re still learning to amputate a leg without taking your assistant’s finger along with it.’

William shrugged and gave Robert a generous grin. ‘So you will, my dear fellow.’ He hopped onto the bench and sat between the saucer-shaped glass dishes.

‘I have seen twenty patients over the past four days from the streets around Mill Yard, all with the same stomach cramps and vomiting. One old woman has already died and some of the children were just lying around like rag dolls when I visited this morning,’ Robert said, running his hands through his hair, which flopped forward again as soon as it was released.

‘You went there?’ William said, clearly astonished, as if just informed that Robert had voluntarily put both hands in an open fire.

‘Aye. How else can I see my patients? As the sick cannot come to me, I must go to the sick. I am a doctor after all.’ Robert stood up, scraping the stool across the polished floorboards. He towered over his friend, who was himself hardly short by usual standards. It’s by linking the disease to those nasty-looking brutes, as you rightly call them, that I will be able to treat the sick more effectively.’

‘And make your reputation,’ William inter commented.

Robert smacked one fist into the palm of the other hand. ‘We are on the brink of new discoveries, William, and I am determined to be in the vanguard of this new science. But I have to be in London, at the heart of medicine, to accomplish that.’ He waved Caroline’s letter aloft and gave it a sideward glance. ‘I just wish that I could convince Miss Sinclair,’ he exclaimed, as a growl sounded from his middle region. His serious expression changed instantaneously. Lifting out a gold hunter from his breast pocket he glanced at it. ‘Well, this watch and my stomach tell me it’s past supper. Have you eaten, Chafford?’

‘That’s precisely why I’ve come by.’ He put his arm around Robert’s broad shoulders in a comradely gesture. ‘I deem it my Christian duty to save you from your serious nature and insist that you accompany me to the Angel and Crown for supper.’

Turning to the part-glazed door Robert grabbed his dark navy frock coat from where he had thrown it absent-mindedly across the professor’s chair and shrugged it on.

Will I do for the Angel and Crown?’ he asked, setting his top hat at a jaunty angle.

William shook his head dolefully. ‘That you will.’ He handed Robert his cane. ‘You really should think about getting a practice in a fashionable resort like Brighton or Weymouth instead of burying yourself and your talents in East London.’ He nudged Robert in the ribs and his friend bent at the waist and gave an exaggerated bow. ‘The widows and dowagers with the vapours would pay readily to have a tall, well-favoured physician like you to cure their ills, Munroe.’

Robert let out a great rumble of a laugh and slapped William on the back, making the other man stagger.

‘I’ll leave the widows to you, Chafford, if you leave the water worms to me.’

After a brisk walk to the Angel and Crown Robert and William entered at the side of the establishment and gave their hats and coats to a lad before making their way to a table. The alehouse was already packed with men drinking and talking, many with flamboyantly attired women by their side. Small spirals of smoke made their way above the crowd, drifting into the rafters and among the hanging lamps.

Robert had visited the Angel and Crown before but had found it full of rowdy apprentice physicians and so often walked the mile or so to the City for more restrained eating establishments. William, with his more outgoing personality, dined more regularly at the Angel and Crown.

Pushing his way through, William spotted an empty table at the corner of the balustrade that separated the two parts of the supper room. Robert stood back to let a blonde barmaid past.

‘Gawd, you’re a fine young gentleman and no mistake,’ she said to him with a saucy smile. ‘I’m Lizzy, if you need a bit of company later, if you understand me like.’ She winked at Robert and squeezed past him, pressing her hip firmly into his groin as she went.

‘I see Lizzy has taken a fancy to you,’ William said as they reached the table.

Robert smiled, but said nothing. He had become accustomed to such boldness since arriving in London.

‘Mr Chafford,’ a voice boomed across the room. ‘Won’t you and your friend do me the honour of joining me for a mouthful of supper?’ asked a large man with a broad Irish brogue.

He beamed at William, his round face shining like a polished apple under the soft light of the oil lamps. He waved at them with one of his massive hands. ‘Make way there for Mr Doctor Chafford, the renowned surgeon, and his friend, fine fellows both of them.’

With his black eyebrows and his curly hair hanging in an unruly twirl in the middle of his brow, the Irishman’s face had a boyish look about it that was at odds with his powerful frame. The expensive clothes he wore fitted snugly – a little too snugly. The huge meal on the plate before him showed why that would be.

A path to the Irishman appeared, as if a scythe had cut a path through the press of bodies. William turned to accept the invitation and Robert followed.

The Irishman untucked his large linen napkin from his collar and stood up as Robert and William reached the table. He grabbed William’s hand, pumping it so hard that his whole body shook.

‘Honoured, I am, honoured, to have you join me,’ he said.

William reclaimed his hand. ‘May I introduce Doctor Robert Munroe, a colleague of mine and the author of Observations on the Diseases Manifest Amongst the Poor, which The Times called “the most comprehensive scientific work published in the past decade”.’ The Irishman raised his eyebrows.

‘Doctor Munroe has recently come from Edinburgh Royal Infirmary,’ William continued, as Robert shot him an embarrassed look. ‘Munroe, this is Mr Danny Donovan, owner of the Angel, and local businessman.’ Robert stepped forward and offered his hand for pummelling. He was not disappointed. His hand was clenched in a painful grip and subjected to the same treatment as William’s had been. The potman pulled back chairs for William and Robert, then stood waiting.

A disarming smile spread across Donovan’s face. ‘Two plates of your mutton stew,’ Danny said to the potman. ‘And make sure there’s some mutton in it or I’ll be wanting to know why.’

The man shot away and Danny fixed Robert with an inscrutable stare.

‘Doctor Munroe. Would that be the same Doctor Munroe who bought the lease on number thirty Chapman Street to open a dispensary?’

‘I am,’ Robert said, registering some surprise. He had only signed the agreement two days before. ‘I must say, Mr Donovan, you are very well informed.’

Danny tapped the right side of his nose twice with a stubby finger. ‘I always make it me business to know who’s doing what around here.’ He pushed the bottle of brandy towards Robert, who poured himself a glass of the amber liquid. He sipped a mouthful.

‘Very good,’ he said, pressing his lips together and passing the bottle to William.

‘They keep it for me, special like,’ Danny said, his gaze still fixed on Robert. ‘You’re a Scot then, Dr Munroe?’ He drained the last of the brandy and raised the bottle for another to be brought.

‘Aye, I am,’ Robert answered, declining the newly opened bottle.

‘And would your father be a doctor too?’ Danny asked, as William poured another brandy.

‘My father’s a minister in the Church of Scotland,’ Robert replied, briefly thinking of the large, cold churches where he seemed to have spent most of his childhood.

‘A minister! God love him,’ Danny said, as two bowls of steaming mutton stew arrived.

After a mouthful of the surprisingly good stew, Robert eyed his host. ‘Apart from the Angel, what are your other business interests, Mr Donovan?’ he asked, his eyes resting briefly on the musicians taking their places in the small orchestra.

‘Mr Donovan is the owner of the Angel, the Town of Ramsgate in Wapping and the White Swan in Shadwell,’ William said, before Danny could answer. ‘Plus a barge or two in the docks. Is that not so?’

The large Irishman inclined his head. ‘The Blessed Virgin has rewarded most generously my small efforts to make a crust or two,’ he said, his humble attitude countered by a sudden inflation of his chest.

‘He is too modest to mention it,’ William said, ‘but Mr Donovan is also a benefactor to a number of charities hereabouts and on the governing board of the workhouse.’

‘Very commendable, Mr Donovan,’ Robert said. ‘However, the people here don’t need charity. They need better housing and clean water.’

For a second Danny’s small eyes narrowed and his lips pursed together. Then the genial expression returned. ‘The people here are blessed by the Queen of Heaven herself, so they are, to have fine gentlemen such as yourselves to doctor to them.’

‘Aye, no doubt that helps, but better living conditions would help more,’ Robert replied with a frown, thinking of the poor wretches he had left to God in his mercy that morning in Mill Yard.

Leaving Danny Donovan to talk to William, Robert turned towards the small stage where the worn velvet curtain moved with the activity behind it. The small band of musicians struck a chord, and conversation around the tables ceased as the plush red curtains squeaked back into the wings.

Into the footlights stepped a young woman. In contrast to most of the other women in the Angel and Crown the woman on the stage wore a simple cotton gown. She swayed in time to the music, her head to one side and a wistful expression on her face as she sang about the beauty of the hills of Galway. The song finished and the singer took a small bow and smiled. She signalled for the leader of the musicians to start the next tune, then let her gaze sweep over the audience until her eyes alighted on Robert.

Robert leant forward and studied her.

Caroline had a passable voice for a house party recital, but the woman now entertaining them had a strong, clear voice that was very different. She was completely unsophisticated with her undressed hair and her fresh, unpowdered and flawless complexion, which glowed under the merciless lights. He had thought at first glance that her hair was the same colour as Caroline’s, a dark brown, but as she tilted her head jauntily towards the light he saw its shimmering red tone and her clear eyes.

She had a fuller figure than Caroline’s, too, more rounded. Under the table his foot started to tap soundlessly against the table leg. As the woman on the stage swayed she invited the audience to join her in the chorus of the song with a wide smile and an arc of her arm. It was an abandoned movement, artless but sensual in its graceful execution.

The song ended and Robert applauded as enthusiastically as any in the room. The singer nodded her head to the maestro and the atmosphere changed from jolly to haunting. In two chords, the woman on the stage changed from vibrant to wistful as she started to sing of a home far away across the sea. Robert was mesmerised.

As she swept her gaze back to him she sent him the echo of a shy smile from under her lashes and Robert forgot all about Caroline, Danny Donovan, William and his mutton stew.

Ellen surveyed the audience to include them in her next song, ‘The Run to the Fair’. Once the audience was focused on her there was less background noise. She was intrigued by the man sitting opposite Danny and her gaze returned to him.

Danny’s guest was wearing a dark navy frock coat of some quality. Next to her boss’s garish outfit it looked positively sombre, but he was elegant in a way that Danny never would be. The light from the candelabra above fell on the angular planes of his face, highlighting the strong jaw and chin. His mop of light-brown hair, showing almost blond in the soft light, was trimmed neatly, but an unruly lock tumbled over his forehead. He leant back in his chair in a casual manner with his arm on the handrail, his strong, sculptured hand resting on the polished oak.

His large frame all but blocked the man sitting behind him and to Danny’s right, yet he wasn’t stout like Danny, but muscular, with long legs that extended under the table to the edge of the raised platform.

As her eyes came back to his face, his dark eyes rooted her to the spot. Reuben struck the chord again and Ellen jumped out of her daze.

She smiled broadly and tried to slow her pounding heart. The man leant forward, putting his elbow on the rail and resting his chin on his hand.

Forcing herself to break free from his gaze, she started the song. Within moments the people in the supper room had picked up the tune and were swaying and singing along with her.

She stole a glance at Danny’s guest. He was still staring intently, a small smile on his lips.

Suddenly Ellen’s heart took flight. This man, whoever he was, approved of her, his expression told her so. He was handsome and he was looking at her. She was enjoying a man’s admiration in a way she hadn’t allowed herself to for a very long time.

The song was exuberant, so Ellen took advantage and jigged a little herself. Roars of approval rose from the floor. She finished with a quick swirl and swept her audience a bow, then gave the crowd two more songs in quick succession. She didn’t look at Danny’s guest again, but she was singing for him.

She caught Reuben’s eye and he smiled at her with a toothless grin. She signalled for him to slow the pace. The violin sent out a melancholy note and then started to play the haunting bars of another Irish tune. The audience quietened as the tempo of the music slowed.

Ellen usually finished with a sentimental song. ‘The Soft, Soft Rain of Morning’ was one of her favourites. It was a ballad, set to a well-known Irish folk tune, about the heartache of being exiled from the home one loved. It would mellow the audience, many of whom were indeed a long way from the land of their birth.

She could hear her voice tremble a little as she glanced around the room, knowing all the while that the stranger had his eyes fixed on her. Thankfully, only she noticed the lapse and soon women could be seen wiping the corners of their eyes as she sang the sorrowful ballad.

Unexpectedly, the sober mood caught Ellen’s emotions. The gaiety of the past moments was suddenly lost as the reality of her life came back to her – a life could never include a man such as the one who hadn’t taken his eyes from her all the time she was on stage.

Disappointment settled on her. She had met the type before. Danny often entertained them. Rich young men who came east for drink and women.

He had introduced her to men like the one looking at her now, and she had seen their eyes light up in the hope of pleasures to come. Ellen had always dashed those hopes smartly. She might have to sing for her supper, but she didn’t have to entertain unwanted attentions for it. She bowed, and left the stage to rapturous applause.

Without speaking, she shot to her small room and slammed the door behind her. She sat in front of the mirror and found her hands were trembling.

There was a light knock on the door and Tom’s head popped around the door. ‘Beggin’ your pardon, Mrs O’Casey, but Mr Donovan says you’re to join ’im and ’is party for a drink.’

Two

The sweet notes of ‘The Soft, Soft Rain of Morning’ drifted over them as Danny studied Robert Munroe from under his ebony brows. He chewed the inside of his mouth thoughtfully.

To Danny’s mind Robert Munroe looked a mite young to be a doctor, and with his well-tailored appearance Danny would have thought him more at home in a ballroom or at the races than in a bloodstained hospital ward.

‘Sings like one of the celestial choir, does she not, Doctor Munroe?’ he said, studying the other man’s face intently.

Doctor Munroe was still looking towards the stage, although Ellen had already left and the curtains were closed. He turned and pulled the front of his waistcoat down.

‘She does,’ he smiled, ‘she does indeed.’

He picked up his glass and downed a mouthful of brandy.

‘Striking too,’ Danny continued, watching Robert’s eyes for a hint of his feelings.

‘Quite,’ Robert replied coolly, but Danny saw what he was looking for. Just for a split second there was a flicker of interest in the doctor’s brown eyes, then it was gone.

He didn’t blame Robert. Ellen was striking. There were prettier women who worked in the Angel but none caught hold of a man’s attention like Ellen.

‘Our Ellen has admirers from all over the city who come to hear her sing,’ he said, trying to see if he could spark Robert Munroe’s interest again.

‘I have no doubt of it,’ Robert replied in a bored tone, but his eyes were still warm.

Danny’s mouth drew into a leer. Educated doctor he might be, a man of letters even, but in his trousers Robert Munroe was just the same as any other man.

On the pretext of greeting some customers behind him, Danny turned away from the table, but out of the corner of his eye saw Chafford lean towards Munroe.

‘I see you think our Ellen a tempting armful, Robert,’ William said in a low voice.

A chair scraped on the floor. ‘I think Miss Ellen is a fine singer,’ he heard Robert reply. There was a change in his voice. ‘And she is fair on the eye.’

William gave a chuckle. ‘Don’t give me that, Munroe. Dash it, man, she’s a looker and no mistake.’

Danny spun back to the table just in time to see Robert smile broadly in agreement. ‘I’ve asked Mrs O’Casey to join us for a glass of port, gentlemen,’ he said.

‘Mrs O’Casey?’ Robert said.

Danny winked. ‘There ain’t a Mr O’Casey, if that’s what you’re wondering.’ Danny pointed with his fork to Robert’s abandoned dinner. ‘Eat up, Doctor Munroe, your dinner grows cold.’

As if she knew she was the topic of their conversation, Ellen appeared from the side of the stage and made her way around the tables towards them. Robert’s dinner remained untouched.

As she snaked around the table she smiled and greeted the regular patrons, Danny watched Robert study her. She hadn’t changed after her performance and still wore the simple cotton dress, its folds clinging to her as she moved. She laughed a couple of times, sending the soft curls of her dark auburn hair rippling around her shoulders.

Her rich throaty chuckle caught Danny deep within. Fury rose in him. Smile at others, would she, but too fine a lady to give him a jig? He should ignore her. He had other women – Kitty and Red Top Molly in Cable Street – but Ellen’s rejection of him only made him hanker after her more. When he had first taken her on in the Angel and Crown he thought her refusal was just her way of raising her price. Others had tried the same thing and, as anyone would tell you, he was a generous man who didn’t mind putting his hand in his pocket for his pleasure. But after a month or two he realised that she wasn’t greedy but respectable: well, as respectable as any woman singing for money in a public house could be.

His gaze flicked back to Robert, who had risen from his chair and awaited her arrival. Anger rumbled around inside Danny as Ellen reached the table.

The tall and soberly dressed doctor and the impoverished supper-room singer stood for a long moment gazing at each other. Danny remained seated and slowly explored his front teeth with a silver toothpick.

‘Ellie, my dear, you have a new admirer,’ he said at length. ‘Doctor Munroe, may I introduce Mrs Ellen O’Casey?’ With a swift movement Danny grabbed her hand and kissed it loudly. She tried to draw her hand from his grasp, but he held on tighter. ‘Ellen, this is Doctor Munroe, a man of letters, and a celebrated doctor from the hospital who has come to cure us of all our ills. And you know Dr Chafford already.’

Ignoring Danny, Robert bowed. ‘It is my great pleasure to meet you, Mrs O’Casey.’

‘Doctor Munroe is wild to meet you, me darling,’ Danny said, his kindly expression not reaching his eyes.

Alarm flashed across Ellen’s face for a second. Then she wiped the back of her hand against the tablecloth and offered it to Robert.

‘I am pleased to meet you, Doctor Munroe,’ she said in a clipped tone.

Her manner at the table was like that of a rabbit caught in the yard by the house dogs. Taking her small hand, Robert bowed over it again. He gazed down on soft, clean fingers and noticed her short, ragged nails. Mrs O’Casey did more than just sing for her living.

‘You sang most wonderfully. So clear and such a range,’ he said, smiling reassuringly at her.

‘You have a musical ear, Doctor Munroe,’ Ellen said.

Robert found that he was looking at the fluid movement of her mouth and thinking how Caroline’s was more often than not drawn together in a sulky pout. Despite her friendly manner Ellen O’Casey was ill at ease. Was it him, William or Danny? Robert didn’t know, but he wanted to dispel the feeling and see Ellen O’Casey smile at him with her eyes.

‘My mother doesna’ think so,’ he said with a light laugh. ‘Five years of music lessons and I could barely whistle a tune. My music teacher suggested that I take up the most traditional of Scottish instruments, the bagpipes, because no one could tell if I was in tune or not.’

Robert laughed, and Ellen and William joined in, ‘her tension vanishing as merriment rose up. He wanted to make her laugh again.

‘No,’ he continued. ‘I am afraid I must leave music to those who have the talent for it. I have a more scientific mind, not at all given to fanciful thoughts,’ he said, trying to look grave and serious. The small twitch of his lips gave him away.

‘As would befit a doctor, and a man of letters,’ she said, taking the seat between him and William.

Danny handed her a glass of port. She placed it on the table untouched.

‘You brought a tear to our eyes singing about the “Old Country”,’ Danny said, flourishing a none-tooclean handkerchief and dabbing the corner of his eye. His hand slipped under the table.

The tension returned to Ellen’s shoulders and she gave him a tight smile. ‘Thank you, Danny.’

‘You know how much I admire you, Ellen dear,’ Danny said as his hand came back into sight. He drummed his fingers lightly on the table and cocked his head towards Robert. ‘As does Doctor Munroe.’

The mask that had just lifted from Ellen’s face snapped back down. Robert silently cursed the Irishman.

‘As do we all,’ added William.

Robert leaned forward and let his eyes settle on her face. He saw her eyes open a little wider under his admiring gaze.

‘The green of your gown suits your colouring, Mrs O’Casey,’ he said, wanting to coax that smile back.

‘Ho, ho,’ Danny snorted, shoving her hard from the side and towards Robert. ‘Admire! I’d say the good doctor here was good and smitten with you, sweet Ellen. No wonder he wants to know you better. Am I right, Doctor Munroe?’

Ellen placed the glass of port on the table carefully and glanced up him. ‘I’d be thinking that for a gentleman with a scientific mind, who is not at all given to fanciful thoughts, that’s powerful poetic, Doctor Munroe,’ she said in a broad Irish accent. ‘You must have practised that line on many a poor girl to turn her head.’

She was wrong. He doubted he had ever remarked on the colour of a woman’s eyes before, not even Caroline’s.

He felt Danny Donovan’s glance on him, mocking him for her rebuff. Anger shot through him. How dare she? A respectable young woman was supposed to thank one for a compliment.

Respectable! Robert almost laughed. Ellen O’Casey was no respectable woman. She was a supper-room singer, only a step up from the garishly clothed women who plied their trade in the Angel. Whatever was he thinking of?

‘You have to watch our Ellen, Doctor Munroe. She might have the look of an angel, but she has the bite of the devil,’ Danny said, flexing his hand a couple of times.

‘I must be off home,’ Ellen said, standing up swiftly. William and Robert rose to their feet.

A sly expression crept over Danny’s face and he looked across at Robert. ‘But will you be disappointing the good Doctor Munroe here? And him just saying he wants to get to know you better, my dear.’

A tight smile fixed on Ellen’s face as she looked back at them. ‘I’m sure there are other women you could introduce him to in the Angel who would be more accommodating company than me.’

Three

Ellen and her mother, Bridget, rose as the first rays of light pierced the bedroom curtains. Silently they gathered their things and left Josie to sleep in the cast-iron bed that the three of them shared. They made their way down the bare-board stairs to their small living room. Kneeling at the blackened range, Ellen coaxed the kindling to flames while Bridget collected the buckets and yokes from the yard.

‘You look tired, Ellie,’ Bridget said, as her daughter threw a shovelful of coal chips on the fire.

Ellen forced a cheery smile and looped the yoke through two of the buckets. ‘I didn’t sleep much.’

Her mother shouldered her two zinc buckets and struggled to stand. Ellen bit her lip. Although Bridget would have cut her own tongue out before admitting it, the daily trip to the pump at the end of the street was getting too much for her. It needed both of them to fetch the water for the laundry they took in daily or they would never get it finished in a day, but seeing the blue hue around her mother’s lips, Ellen wondered how much longer she would be able to make the journey.

Worry about tomorrow’s woes tomorrow, she told herself. She opened the door to the street, letting in the pale morning light. It had rained overnight and the dirt outside was now mud and mingled with a small stream of pungent fluid meandering towards the bottom of the street. Although it was barely and hour after dawn, the pavements were already alive with people. Widow Rosser was already scooping up her harvest of dog, dirt from the surrounding streets to sell to tanneries on the Southwark side of the river. Ellen and Bridget waited until she reached of the street then stepped out.

‘That devil Danny been after you again?’ Bridget asked, crossing herself swiftly.

‘It’s not Danny. I’m just out of sorts, that’s all,’ Ellen said.

As they made their way to the pump Ellen and Bridget were nearly knocked over by five or six small boys dressed in rags. Despite being barefoot, the mudlarks joked with each other about the rich pickings to be had in the low-tide slurry.

Ellen lapsed into her own thoughts as Bridget greeted her friends who were on the same early morning errand. Danny she could deal with. Disturbing thoughts of Doctor Munroe she could not.

Was he going to call on her, take her to the ball, invite her to take tea with his mother? Of course not! How could she have let herself dream such a thing? But when his eyes had settled on her that was exactly what she had dreamed. For a brief moment she had allowed herself to imagine a man like the doctor wanting and loving her for life, not just for a night or two for the price of a couple of shillings.

All around them the men of the area trudged towards the docks and waterfront to queue in the hope of a ticket to work. Ellen and Bridget stopped and waited at the pump. Bridget looked around swiftly and then said in a low voice, ‘Hard as it is for us, I bless the day Michael O’Casey was taken.’ She spat on the ground. ‘The devil take his rotten soul. You wouldn’t have survived his fist much longer, my precious.’

Ellen’s tongue went to the side of her mouth and the space where two teeth once sat.

‘When Michael’s drunken fist knocked the child from you, I thought I was going to lose you, Ellie.’

Bridget ran her calloused fingers gently along her daughter’s face. Then she started coughing. Ellen put her arm around her, but her mother waved her away. ‘I’m fine,’ she wheezed, then punched her chest. ‘Just the early morning dust shifting.’

A dull ache settled on Ellen’s own chest. She thought of the poor infant, born before its time. Her mother was right. If Michael hadn’t died when he did she would have been in her grave by now. How would Josie and Bridget have fared then?

Forcing her mind back to the present, she stepped forward and put her hand to the pump, working the iron handle until a stream of brown water gushed out. She filled the four buckets and they started back to the house.

Ellen glanced at her mother. There were beads of sweat on Bridget’s brow and upper lip. She looked old and grey, like many of the other women who lived in the squalid conditions around the docks.

‘A few more months and we will be off, you, me and Josie,’ Ellen said, with a too-bright smile. We’ll see Joe and his wee’ uns in America, so we will.’

Bridget smiled, but didn’t answer. She was concentrating on carrying the buckets of water without spilling them.

Entering the house, they found Josie already washed and dressed in her dark serge dress with a white apron over it. Her bright, reddish-brown hair was tied back in two neat plaits that swished across her back as she moved. She grinned at her mother and grandmother as they entered the room. Ellen frowned. Josie, like the young Ellen, was maturing early. Thankfully, the shapeless dress she wore disguised her burgeoning figure.

‘Morning to you, Gran,’ she said, giving Bridget a noisy kiss. The older woman’s stern expression melted as she gazed on the leggy thirteen-year-old bouncing around the room.

Maybe we will have enough to go to America in three months, Ellen thought. If I did a Thursday night at the Town of Ramsgate and Mammy took a couple more bundles of washing we could be on a ship by October.

Bridget started coughing again and Ellen’s brows drew together.

‘Have a bowl of porridge, Mammy, before you and Josie set out,’ Ellen said, leading her mother to the chair and table by the window.

‘’Tis Josephine who is your child, Ellen Marie, not me,’ she said sharply. But she flopped into the chair and made no complaint when Josie placed a bowl of steaming porridge and a mug of tea before her.

Ellen gathered up her coat and slipped on her day shoes. ‘You stay here and watch the copper, Mammy, I’ll go and fetch the linen.’

‘I’m not ready for to be left by the fire while others work,’ her mother said. She leant back in the chair and hugged the mug of hot tea to her. ‘I’ll catch you up presently.’

*

Robert wiped the blood from his hands and arms, then headed for the sluice room to clean up properly. It had been a difficult operation.

The locals had brought Bobby Reilly in straight from the docks, his crushed arm hanging in ribbons from his shoulder. After he had been lashed down on the operating table, Robert, as the physician on duty and William, his surgical counterpart, had been summoned.

Although Reilly had been made near insensible by the drink poured down his throat, he still had some fight left in him. It took the strength of four orderlies to hold him down while William, assisted by Robert, amputated his arm with a hacksaw.

Robert went into the tiled area with its deep sinks. He grabbed the coal-tar soap and scrubbed at the blood on his arm before it dried. William followed him in.

‘Bad business, a young man in his prime losing an arm like that,’ William said, taking the soap from Robert.

‘Bad business for his family,’ Robert snapped. ‘He has four young children and a sickly wife. They’ll be lucky if they avoid the workhouse.’

He threw down the towel, ran his fingers sharply through his hair and frowned at the dirty water in the porcelain bowl.

‘You seem less than yourself today, Munroe,’ William remarked dropping the towel in the washing basket.

Robert scowled out of the window. ‘I didn’t sleep very well. Too much noise.’

That was a barefaced lie. He hadn’t slept very well because his mind was full of that sharp-tongued Ellen O’Casey. He had spent a futile hour staring at the ceiling and thinking of her rude response to his compliment. Then another hour remonstrating with himself for being such a fool as to care.

‘Are you coming to the mess for a coffee, Rob?’ William asked. It was their habit after an operation.

He shook his head. ‘I thought I might take a stroll along to Backchurch Lane while I have a free moment.’

‘Going to see your lady love then, are you?’ Chafford asked, glancing to the foot-long, brown package that had delivered to the theatre while they operated.

Robert grinned.

‘I’ll see you at dinner,’ he said, rebuttoning his cuffs and slipping on his jacket.

Stepping out of the hospital, Robert stood under the classical portico for a moment and surveyed the scene. He tucked the package under his arm drew a deep breath, and made his way down the white stone steps to the market. The noon stagecoach to Colchester passed just as he reached the bottom, its driver whipping the horses into a steady trot towards the open expanse of Bow Common and the Old Ford across Lea River.

Recognising him as one of the doctors from the hospital, a number of the stallholders touched their forelocks as they cried ‘pippin, luverly pippin’, ‘new water fresh’ or ‘three a penny Yarmouth Bloaters’. The salty smell of fish mingled with the sweet scent of early flowers, while the meaty aroma from the tray balanced precariously on the top of the pieman’s head made Robert’s stomach rumble.

He turned west towards Aldgate. As he made his way past the stalls his mind settled. He relegated Ellen O’Casey and her cynical opinions to their rightful place in the grand scheme of things. He had even begun to see the whole incident in an amusing light.

Then he saw her.

She was standing by a fruit and vegetable stall dressed in a homespun, brick-red day dress and a short black jacket with worn elbows. Her face was shielded from the sun by a narrow-brimmed straw bonnet secured with a tie to one side. The whole ensemble was probably second-or even third-hand. As she stood, the wind billowed her skirt, then flattened it against her body, giving Robert a new image to turn over in his mind. She and the rotund stallholder were deep in conversation. He stood for a moment watching her, then walked towards her.

Ellen scratched the skin of the new potato to reveal its white flesh beneath.

‘Are you going to buy that, missis, or are you just making it ’appy by giving it a feel?’ asked a rasping voice beside her.

‘I’ll have it and two of its friends, if you please, Jimmy Flaherty, and knock the mud off before you weigh them. I’m not paying for dirt I can get free on my boot,’ Ellen answered.

After collecting the sacks of washing from the regular houses, Ellen was relieved to find her mother almost her old self when they returned. She had left Bridget and Josie scrubbing in the backyard.

She had decided to walk to the Waste, as the scrub land between the city and the Essex countryside proper was called, to get dinner and a bit of something for tea. Watney Street was a nearer market but the stall near the white chapel of St Mary’s often had fresher fruit and vegetables. Many of the journeymen from Essex skimmed goods from their loads and sold them to the stallholders as they passed by on their way to the City.

Ellen eyed a couple of cooking apples. They were old stock and had probably been kept over from the last harvest but they looked whole enough. If she baked them, they’d do for tea.

‘I’ll have those three as well,’ she said, pointing at the apples, ‘and an onion, two carrots and half a swede.’

Jimmy grinned at her as he hung the apples in the scales, ‘Ow’s yer mother?’

‘You know my mammy.’

‘And that pretty Josephine?’

Ellen smiled. ‘Growing like a flower in an Irish meadow.’

Jimmy turned his round, jovial face to the sky. ‘Spring’s round the corner, wouldn’t you say, Ellen?’

Copying Jimmy’s movement Ellen too tilted her face to the sun and took a deep breath in. ‘I certainly would,’ she said, and caught him looking beyond her. Wondering what the stallholder was staring at, she turned.

‘Good day to you, Mrs O’Casey.’

Having tried – and failed – to remove the image of Doctor Munroe from her mind all night, seeing him standing in the fresh morning sunlight not two foot from her was more than a little disconcerting.

‘Doctor Munroe,’ she said, hoping only she could hear the tightness in her voice. She gathered up her basket from the cobbles and balanced it on her hip. ‘Are you buying your su . . . supper like the rest of us?’

A smile spread across the doctor’s face.

‘No, just a small gift. Two Seville oranges, if you please,’ he said to Jimmy. He smiled broadly at Ellen. ‘Oranges are very good for you, you know, if you’ve been poorly.’

The stallholder wrapped the oranges and handed them over. Adjusting the package under his arm Doctor Munroe paid for his purchase and turned back to her. His eyes flicked down to the basket she held. Ellen turned towards the City.

‘I see you are going in the same direction as I am, so please let me carry that for you,’ he said, taking hold of the basket handle.

‘But you already have your hands full,’ she replied watching him manoeuvre the long, flat package he was carrying.