20,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

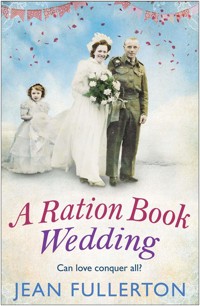

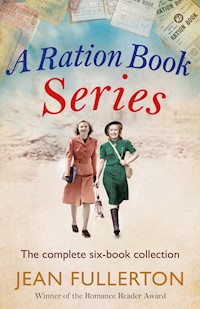

The complete six-book collection of the Ration Book series, collected together for the first time. From the queen of the East End, Jean Fullerton, the Ration Book series features the Brogan family and their community in London's East End during WW2. Now enjoy the full series in its original form. Ration Book Series A Ration Book Dream A Ration Book Christmas A Ration Book Childhood A Ration Book Wedding A Ration Book Daughter A Ration Book Victory

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Jean Fullerton is the author of nineteen historical novels. She is a qualified District and Queen’s nurse who has spent most of her working life in the East End of London, first as a Sister in charge of a team, and then as a District Nurse tutor. She is also a qualified teacher and spent twelve years lecturing on community nursing studies at a London university. She now writes full time.

Find out more at www.jeanfullerton.com

Published in eBook in Great Britain in 2022 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Jean Fullerton, 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022

The moral right of Jean Fullerton to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novels in this bundle are entirely works of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

E-book ISBN: 978 1 83895 654 7

Corvus

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk/corvus

To my darling husband of 40 years, Kelvin

Chapter One

GRIPPING THE TWO Kirby grips tightly between her lips, Matilda Mary Brogan or Mattie as she was known to all and everyone, carefully slid the comb of her sister Cathy’s headdress into place and then, taking each pin in turn, fixed it there.

‘There you go,’ she said, smiling at Cathy in the mirror.

Cathy, who at eighteen was two years Mattie’s junior, had hair the colour of ripe corn and storm grey eyes, like their father’s, while, in complete contrast, Mattie had inherited the dark chestnut locks and hazel coloured eyes of their mother.

‘It’s so pretty.’ Touching the wax orange blossoms with the tips of her fingers, Cathy turned her head from side to side. ‘I just hope it stays on in this wind.’

‘It ought to, I’ve anchored it with enough pins,’ Mattie replied. ‘Besides, it looks like it’s brightening up.’

Cathy gave her a wan smile. ‘You mean it’s stopped thundering.’

It was the first Saturday in September and instead of catching the 5.30 from London Bridge to Kent for the hop harvest, which is what they’d done on this day of the year ever since the girls could remember, the women of the family had been up since the crack of dawn preparing for Cathy’s big day.

Mattie lived with her parents, Ida and Jerimiah Brogan, at number 25 Mafeking Terrace which ran between Cable Street and the Highway in Wapping, just a few roads back from London Docks. Their road was lined with Victorian workers’ cottages and was just wide enough for two horse carts to scrape past each other. It had originally been called Sun Fields Lane but after Baden-Powell and his handful of troops were relieved at Mafeking, it was renamed in their honour.

With three upstairs rooms, a front and back parlour plus a scullery, the houses in the street were probably considered spacious when they were constructed a century and half ago but with seven adults and two children living under its roof, the ancient workman’s cottage was straining at the seams.

Mattie’s parents had the largest upstairs room, overlooking the street, her brother Charlie, who was three years older than her, and nine-year-old Billy-Boy squashed into the minute back room while Mattie shared the third bedroom with her sisters Cathy and Josephine. This was where she was now, standing listening to her mother and grandmother bustling around downstairs as they prepared plates of sandwiches for the wedding breakfast.

As the women had used the facilities at the Highway’s public baths the evening before, they set to making plates of sandwiches still in their dressing gowns and curlers, to be taken around to the Catholic Club where the wedding breakfast was to be held.

While the women of the family worked on the refreshments, Mattie’s father and her brother Charlie changed into their Sunday togs and had left twenty minutes ago to sort out the transport. As chief bridesmaid, Mattie had been given the task of helping Cathy into her wedding dress while the rest of the family got everything ready.

There was a crash downstairs.

‘For the love of God,’ screamed her mother’s voice from the scullery below. ‘For once will you let up on your bloody fault-finding, Ma?’

‘Fault-finding, is it?’ trilled Queenie Brogan, Jerimiah’s sixty-two-year-old mother. ‘Sure, am I not just trying to stop you being the laughing stock of the street, Ida, with your—’

The kitchen door slammed.

In the reflection, Cathy smiled at her. ‘They don’t stop, do they?’

‘When are they not?’ Mattie rested her hands lightly on her sister’s slender shoulders and smiled. ‘You look so beautiful and every bit the blushing bride.’

A pink glow coloured her sister’s cheeks. ‘I just hope Stan will agree.’

‘Of course he will,’ said Mattie. ‘In fact, I wouldn’t be surprised if he fainted away at the very sight of you.’

Cathy giggled. ‘Did you ever think I’d be married before you, Mattie?’

‘I can’t say I gave it much thought,’ Mattie replied, poking a stray pin in a little firmer.

Cathy turned her head and fiddled with a curl. ‘Because I’m sure you’ll meet the right man someday.’

‘I’m sure I will, too,’ Mattie replied. ‘Someday, but I’m not in any hurry.’

Cathy spun around on the stool and took her hands.

‘And I don’t want you to worry that you might end up an old maid on the shelf, cos you won’t,’ she said, an earnest little frown creasing her powdered brow.

Mattie suppressed a smile. ‘I’ll try.’

Giving her hands a reassuring squeeze, Cathy turned back to admire her reflection again. ‘It seems wrong somehow to be so happy what with everything else that’s going on,’

‘Nonsense,’ said Mattie fluffing up the short cream veil again. ‘A wedding and a good old-fashioned knees-up is just what everyone needs to take their mind off things.’

Cathy bit her lip. ‘Do you think it will be war?’

Mattie sighed. ‘I can’t see how we can avoid it. And what with the blackout each night and trenches being dug in Shadwell Gardens, it’s not as if we haven’t been preparing for it for months, is it? I mean, we’ve had the Civil Defence up and running for over a year, the blackout curtains up since Whitsun and it must be costing the goverment a fortune in printing as every day the postman’s shoving a new leaflet through the door.’

‘But Stan says there is still a chance Hitler will think better of it and leave Poland,’ Cathy said.

Mattie forced a bright smile. ‘Perhaps he will. Now, you know how Rayon crumples, so if I were you I’d stand up for a bit to let the creases fall out.’

Cathy obediently got to her feet.

Mattie knelt down and tugged gently at the hem of Cathy’s dress to get the folds in the right place. The dress, with its padded shoulders, square neckline, cross-cut panels and high waistline, suited her sister to perfection. Cathy had fallen in love with the design two years ago and cut it out from the Spring Brides special edition of Woman’s Own; just after she’d turned sixteen and their father had agreed for her and Stan to start walking out properly. Mattie had sweet-talked Soli Beckerman, the elderly pattern-cutter at Gold & Sons where she worked as a machinist, to make it for her and he’d done a beautiful job.

Satisfied with the way the fabric was draped, Mattie rocked back on her heels and stood up, straightening the skirt of her own apple green bridesmaid dress. Bending forward, she checked her hair only to find, as always, several wayward curls had escaped.

The door burst open and their mother strode in.

Ida Brogan was halfway through her forty-fourth year and at five foot five could look all three daughters more or less in the eye. If the faded wedding photo on the back parlour mantelshelf was to be believed, two decades ago she would have comfortably fitted into any of Mattie’s size twelve dresses but now, as mother to a brood of Brogans, her hips had spread accordingly. That said, she could still sprint down the road after a cheeky youngster if the occasion arose.

With the exception of Christmas Day, Good Friday and Easter, her mother usually donned a wraparound apron and hid her silver-streaked dark brown hair that was once the same rich chestnut tone as Mattie’s under a scarf, but today Ida wore a navy suit and a smart pink blouse with a fluted front and a bow that tied at her throat. In addition, she’d bought herself a new felt hat which she’d decorated with a vast number of artificial flowers. However, in keeping with the government’s latest directive she’d enhanced her ensemble with the cardboard box containing her gas mask which was now hanging from her right shoulder by a length of string.

‘How are you two getting on . . . ’ She stopped as a rare softness stole across her rounded face. ‘Don’t you look a right picture?’

‘Thanks, Mum,’ said Cathy, smiling shyly at her. ‘Mattie’s done such a good job, hasn’t she?’

Ida nodded. ‘Turn around and let me have a gander at the back.’

Cathy did a slow turn on the spot.

‘Beautiful,’ said their mother with a heavy sigh. ‘You’ve done your sister proud, Mattie.’

‘Thanks, Mum,’ said Mattie, enjoying her mother’s approval.

Ida winked. ‘Good practice for when you and Micky get wed, isn’t it? I suppose he’s meeting us at the church.’

Mattie gave a wan smile.

‘Just as well,’ continued her mother. ‘The way Queenie’s been lashing everyone with that tongue of hers, she’d have given the poor boy the rough edge of it if he’d been here this morning.’

She caught sight of her daughters’ alarm clock on the bedside table and scowled. ‘Eleven-thirty! Where’s your bloody father?’

‘It’s all right, Mum, the church is only five minutes away so we’ve got plenty of time,’ said Mattie. ‘I’ll take a look to see if he’s coming.’

Going to the window, which had been criss-crossed with gummed-on newspaper, she threw up the lower casement and looked out.

Heavy grey clouds still hung low over the London Docks just to the south of them but, mercifully, there were a few blue patches forcing their way through.

‘Can you see him?’ asked her mother.

‘Yes,’ Mattie replied as she spotted Samson, her father’s carthorse, turn into the street. ‘He’s just coming.’

Her father, Jerimiah Boniface Brogan, sat on top of his wagon. He was wearing his best suit with a brocade waistcoat beneath, a red bandana tied at his throat. The wagon with Brogan & Son Household Salvage painted in gold along the side, which was usually piled high with old baths, bedsteads and broken furniture, had been scrubbed clean the previous day. It was now festooned with white ribbons and even Samson’s bridle had bows tied to either side. As the cart rolled over the cobbles, the neighbours stopped their Saturday morning chores to watch the bride set off to church.

Ida bustled over and, pushing Mattie aside, thrust her head out of the window.

‘About bloody time,’ she called as the cart with Mattie’s father sitting on the front came to a stop in front of the house.

Although Jerimiah was three years older than his wife, his curly black hair showed not a trace of grey and, with fists like mallets and forearms of steel, he could still wipe the floor with a man half his age. According to Grannie Queenie, her one and only child had been born in the middle of the Irish sea during a force nine gale and had had the furies in him ever since. As boisterous as a drunken bear and with a roar like a lion, Jerimiah Boniface Brogan wasn’t a man to mess with but his yes was yes and his no was no and everyone knew it. But to Mattie he was a loving smile and a safe pair of arms to cuddle into and she adored him.

He stood up and whipped off his weather-beaten fedora.

‘And a top of the morning to you too, me sweet darling,’ he called, sweeping his enraged wife an exaggerated bow.

‘Never mind the old codswallop,’ Ida shouted back. ‘Where the hell have you been?’

‘Just socialising with a few friends in the Lord Nelson,’ he replied, setting his hat back at a jaunty angle. ‘Is the bride ready?’

‘Of course she’s ready,’ her mother replied. ‘She’s been ready for hours.’

Jerimiah jumped down. ‘Then her carriage awaits.’

‘Right, I’ll take Billy with me and I’ll tell Charlie when I see him to make sure he keeps an eye on Queenie,’ said her mother, hooking her handbag on her arm. ‘I don’t want her nipping into Fat Tony’s to place a bet on the two-thirty at Kempton Park on her way to church.’

She turned to leave, then stopped and gazed at her middle daughter.

Tears welled up in her hazel eyes.

‘You look so lovely, sweetheart,’ she whispered.

Ida hugged her to her considerable bosom for a moment then, taking a handkerchief from her sleeve, hurried out of the room.

‘Ready?’ Mattie turned to her sister.

Cathy nodded. Her gaze rested on the double bed the three sisters shared. ‘It’ll seem strange not snuggling up with you and Jo each night though.’

Mattie smiled. ‘No cos you’ll be snuggling up to your new husband instead.’

Cathy laughed.

‘But at least after today you won’t have to hear Ma and Gran arguing the toss from dawn to dusk,’ said Mattie.

‘Thanks be to Mary, for that,’ Cathy replied.

They exchanged a fond look, then Cathy threw her arms around Mattie. With tears pinching the corner of her closed eyes, Mattie hugged her back.

‘Let’s be off then,’ said Mattie, hooking both their gas masks over her shoulder. She picked up her sister’s white confirmation Bible and rosary, then handed them to her. ‘After all, you don’t want to keep that groom of yours waiting.’

Shuffling past the buffet table with the other guests, Mattie picked up a meat paste sandwich and two sausage rolls and put them on her tea plate. Well, perhaps table was dressing it up a bit as Cathy and Stan’s wedding breakfast was in fact laid out on three scaffold planks that had been placed over the snooker table with a double sheet serving as a table cloth.

She was in the Catholic Club’s main hall which had a stage at one end and a bar at the other. Situated around the corner from the church, it had been built fifty years ago and was a square, functional building typical of the Edwardian period. Its high windows let in light despite the fine mesh that had been fitted over them to protect the glass from the threat of being used as target practice by the local lads. The lower half of the room was covered in brown glazed tiles while the upper half was emulsioned in cream. Faded photos of past club presidents lined the walls in neat rows and there was a green flag with a golden harp at its centre hanging from a pole to the left of the stage.

The hall was the focal point of the community and hosted everything from the Brownies, Guides, Cubs and Scouts, who used it on Tuesdays and Wednesdays, to Irish-dancing classes on a Thursday and a baby clinic on Tuesdays. The East London Temperance League used to use the hall for their meeting on a Thursday evening but, after the police were called once too often, they had to move. It wasn’t really the teetotallers’ fault, but having them downstairs when the bar upstairs was crammed with dockers downing pints was asking for trouble. It was one of the few places that could accommodate a wedding party or a wake so the hall was always in demand.

Mattie added a pickled egg to her plate, then squeezed out of the fray and made her way back to her table in the corner and sat down.

The sun had shone as they’d arrived at St Bridget’s and St Brendan’s on Commercial Road. Her brother Charlie had met them as they arrived. After filling Samson’s nose bag with oats, Charlie had tied up the horse and wagon in the alley behind the church and joined his family in the church. He’d slipped in alongside Queenie as their mother instructed.

The wedding service and a full nuptial mass had lasted just short of two hours after which the family quickly got themselves into the various groups for the photos before heading off to devour the spread awaiting them.

That was almost an hour ago and now the formal speeches were over, the buffet had been opened and the guests from both sides of the family were munching their way through it. Although, to be fair, the Brogans and their kindred made up most of the wedding party and the left side of the church had been packed, cheek by jowl, while the groom’s family barely filled three pews.

Stan was an only child whose father had died when he was three so his immediate family was his mother Violet. She had chest problems and was more or less wheelchair bound. Being almost a decade older than Mattie’s mother, Violet Wheeler favoured the low-waisted styles and pastel colours of the Edwardian age so she was wearing a lilac and grey two-piece trimmed with lace and seed pearls. Mattie spotted Violet sitting in the corner furthest away from the stage surrounded by the handful of distant relatives she’d rounded up for her son’s nuptials and Stan’s best man, an old school chum.

Mattie’s gaze drifted onto the new bride and groom who were sitting, heads together, on the top table.

‘I suppose you’re dreaming it were you sitting up there,’ a familiar voice behind her said.

Mattie turned and smiled up at her dad, who was standing with a pint of Guinness in his beefy hand behind her.

‘I’m certainly not,’ she said, as he turned the chair next to her and sat astride it.

He glanced around. ‘So where is your young man, then?’

‘Micky’s not coming because we’re not walking out any longer,’ Mattie replied.

Jerimiah regarded her ruefully. ‘But he’s a grand chap and worships the ground you walk on.’

Mattie smiled. ‘I know, but he thinks I should marry him and I think I should get my Higher School Certificate and go to college.’

Her father grinned. ‘And so you should. You’re too bright to waste your life in that blooming sweatshop. We’ll be at war again tomorrow and, just like the last time, once the men start marching off to fight, women will be called upon to take over. And, sad though I am to say it, Mattie, this is a chance for you to make something of yourself.’

Mattie smiled. ‘And I’m going to. The Workers’ Educational Association are running matriculation classes in Toynbee Hall and I’m going to enrol when they open for the new term in two week. That’s assuming the gas attacks the government has warned us about don’t get us first.’

‘Well, if they do at least you won’t have the need to tell your mother about Micky,’ said her father.

‘No, I won’t,’ laughed Mattie.

Jerimiah’s gaze shifted down to the far end of the room and a sentimental expression lifted his heavy features. ‘But she does look a picture, though?’

‘She could be the fairy queen herself,’ Mattie replied, feeling extraordinarily pleased to see her sister so happy.

‘She done well for herself, has Cathy,’ said her father.

Mattie’s eyes shifted from her sister to the young man sitting beside her.

At twenty-seven, Stanley Kitchener Wheeler was eight years older than Cathy with thick light brown hair and dark brown eyes under a low brow. At just five foot six he topped his bride by only three inches, which was why Cathy now wore flat shoes most of the time. He’d treated himself to a new suit for his wedding but, rather than a sober black or grey one, he’d chosen a square-shouldered American style in brown with a broad chalk stripe, a style frequently seen in snooker halls and at dog tracks.

‘I’ll tell you no lie, Mattie,’ her father continued. ‘I wasn’t all that pleased when she brought him home, not after the shady reputation he’d got himself at the boxing club, but since he got that old lorry and set himself up as a market driver he seems to have put all that behind him, especially now he’s on the committee in that there peace thingy malarkey.’

‘You mean the British Peace Union that meet here on a Thursday night?’ asked Mattie.

‘That’s the fellas,’ her father replied.

‘I suppose so,’ Mattie conceded. ‘But I can’t say I’m not a bit surprised to hear he’s a member as he’s never struck me as being interested in politics.’

‘With Hitler marching across Europe, there are a lot of people more interested in politicking now than they were a year ago,’ her father replied. ‘And, anyway, I don’t mind what he’s involved in as long as he looks after my little girl. If he takes care of her half as well as he does his old mother, I’ll be more than happy.’

Raising his glass to take another mouthful, something caught her father’s eye.

‘For the love of Mary!’ he snapped, placing his glass back on the table. ‘Can they not give over just for one blessed day?’

Mattie followed his gaze to the refreshment table where her mother and Queenie were standing toe to toe and glaring at each other.

‘I’ll give you a pound to a penny it’s Billy again. Isn’t the boy the very Devil incarnate, but whatever it is your mother will be making excuses for him,’ said her father.

Grasping his pint in his enormous hand, he started across the dancefloor.

Mattie popped the last piece of sausage roll in her mouth, licked the grease from her finger and then, picking up her empty glass, she stood up and walked to the bar.

Pete Riley, the club manager, was standing behind it polishing a glass. As children, Pete and Jerimiah had lived three doors apart and, if their stories were to be believed, had spent their days dashing barefoot around the streets and alleyways, up to no good. Pete was now father to nine and grandfather to three more. His hair, once black, was now a steely grey and his belt buckle strained on its last notch.

‘Another G and T please, Pete,’ Mattie said, setting her empty glass on the towelling mat with Indian Pale Ale printed on it.

Pete stowed the used glass in the rack above the counter and picked up a clean one from the shelf behind the bar. ‘You know it’s against club rules to serve women at the bar.’

‘Of course I do,’ said Mattie brightly, ‘which is why my dad is asking you to put it on his slate as I’m collecting it for him.’

Pete pulled a face. ‘Mattie . . .’

‘Please.’ She gave him a dazzling smile and batted her eyelashes. ‘It is my sister’s wedding.’

Pete sighed and flipped the tea towel over his shoulder. ‘All right, just this once but don’t let the committee hear about it or they’ll have my guts for garters.’

Mattie blew him a kiss and leaned back on the bar.

Casting her eyes around the room, she spotted her friend Francesca. They had known each other since they’d been placed together in Miss Gordon’s class aged four and a half. Francesca lived with her father and brother above their fish and chip shop on Commercial Road, next to Fish Brothers’ pawnbrokers.

An inch or two taller than Mattie, Francesca had clear olive skin, almond-shaped ebony eyes and straight black hair so long she could sit on it, but today she’d whirled it into a plaited bun. She was wearing a navy felt hat with matching shoes and bag and her sky blue dress hugged her slender figure.

She was sitting in one of the side booths toying with an empty glass and gazing across the room with a sad, faraway look in her eyes. The object of her affection, Mattie’s brother Charlie, was standing with a handful of his mates on the other side of the room.

‘Can you make that two, please, Pete,’ she added, over her shoulder.

Having got her drinks, Mattie wove her way through the dancing wedding guests to join her friend.

‘You looked like you needed a top-up, Fran,’ she said, putting the glass in front of her friend.

Francesca looked up and smiled. ‘Ta. I was just thinking you’ve all given your Cathy a right good do.’

‘Yes, we have, haven’t we?’ agreed Mattie. ‘I know Mum’s pleased with the way everything’s gone and there are even a few sandwiches left for Dad’s lunch tin on Monday.’

‘And everyone’s enjoying themselves,’ continued Francesca as the two fiddlers Jerimiah had hired struck up a familiar reel.

‘Yes they are,’ agreed Mattie, ‘particularly Gran.’ She indicated Queenie, who barely scraped four foot ten, had white candy floss hair, a face like a pickled walnut and a temper like a firecracker. Weighing no more than half a hundredweight soaking wet and just two years into her seventieth decade, she still did the family washing by hand in the backyard and put it through the mangle every Monday.

In her younger days, Queenie had been well known for storming into public houses along the Knock Fergus area of Cable Street to fetch Grandpa Seamus away from the drink.

She had come to live with Mattie’s family after Seamus was found face down in the Thames mud. Although Queenie had maintained that he must have been done to death by some foul felon, the coroner recorded accidental death due to excessive alcohol – a more likely verdict given that he’d been seen toasting the Irish Free State’s tenth anniversary in every public house on the Highway for the three days prior to his death.

Queenie had marched into number 25 Mafeking Terrace with her portmanteau in one hand and a cage containing Prince Albert, her ancient grey parrot, in the other and had commandeered the front parlour. That was seven years ago and she had steadfastly resisted all of Ida’s attempts to wrest it back ever since.

Mattie’s gran, knocking back gin like there was no tomorrow since they’d arrived, had discarded her moth-eaten fur coat three sizes too big and had taken to the dancefloor. She was holding her skirt above her knees with one hand and was hopping from one spindly leg to the other and swinging a red handkerchief in the air with the other.

‘Well, it is a party,’ laughed Francesca. ‘I thought your Aunt Pearl would be here?’

‘I didn’t,’ Mattie replied. ‘Since she’s taken up with that new man of hers, she thinks she’s too posh for the Catholic Club, but I know Mum’s glad she hasn’t shown her face.’

A roar of male laughter cut through the noise and Mattie looked across at her brother.

Having completed the formalities of his sister’s wedding, Charlie had dispensed with his jacket and now stood with his top two shirt buttons open, his tie loosened, his sleeves rolled up and Stella Miggles draped over him.

‘I really don’t know what he sees in her,’ said Francesca with a catch in her voice.

‘Nor do I,’ agreed Mattie.

In truth, with her twenty-four-inch waist and a D-cup bra, Mattie could see exactly what her brother saw in Stella. Unfortunately, Stella’s substantial bust and lenient attitude towards roving hands blinded Charlie to all else including, sadly, Francesca.

Mattie picked up her drink and knocked it back.

‘Come on,’ she said, grasping her friend’s hand. ‘This is a wedding not a wake so let’s go and grab ourselves a couple of spare men.’

‘And so as we contemplate the dark days ahead, we can draw comfort from St Augustine’s words: “that others, subject to death, did live, since he whom I loved, as if he should never die, was dead”,’ Father Mahon said, his soft tones drifting over the congregation. ‘Or was it St Francis who said that? I’m never quite sure. Or perhaps it was Pope Clement VIII. No . . . no, I’m almost certain it was the saintly Bishop of Hippo who . . . ’

Mattie shifted onto her other hip to relieve the numbness in her rear and stifled a yawn.

It was Sunday morning and she was sitting amidst the gothic splendour of St Bridget’s and St Brendan’s. With its plaster Stations of the Cross on the walls, a lady chapel complete with a life-size statue of the Virgin Mary and the painting of the Last Supper in the top chancery, it was a place as familiar to Mattie as her family’s kitchen.

The family usually attended the 10 o’clock mass on Sunday but their mother had said that, just this once, they could go to 4 o’clock service instead, which was a blessing as Mattie’s father had still been in full voice at half eleven.

Having seen the bride and groom off on their honeymoon – three days in Southend – Jerimiah had taken to the stage. He’d led the assembly through his usual repertoire of ‘Danny Boy’ and ‘When Irish Eyes are Smiling’ before moving on to the more traditional ‘Wearing of the Green’. Not to be outdone as her son’s deep baritone gave up the last note of ‘Fields of Athenry’, Queenie jumped on stage too and treated the company to a rendition of ‘She Moves Through the Fair’ that left not a dry eye in the room.

After the celebrations finally broke up just before midnight, Mattie, her mother and Jo had spent another hour clearing away the buffet debris and tidying away. Having successfully navigated their way home through the blacked-out streets by way of the white stripes the council had recently painted on the kerbs to prevent people walking out into the road, they finally fell into their beds as the clock on the mantelshelf in the back parlour chimed one.

‘For the love of Mary, what is he blithering about?’ said her mother, who was sitting in the pew to Mattie’s right and wearing the same outfit as the day before.

‘I’ll thank you, Ida, to remember where you are,’ snapped Queenie in her loudest whisper. ‘And not to be speaking of dear Father Mahon in such a way.’

Despite consuming half her weight in gin the night before, Mattie’s grandmother had been up with lark. By the time the rest of the Brogan family had stirred, she’d already been to get fresh bread from the Jewish baker around the corner and had a pot of tea brewing.

She was currently sitting on Mattie’s left wearing her fur coat, battered felt hat and, as it was the Lord’s day, her dentures, too.

‘I know full well where I am, Queenie,’ Ida replied. ‘But I’m wondering if Father Mahon does.’

Queenie’s lined face softened. ‘The poor dear man has such a weight on his shoulders at the moment and it will surely be a blessing for him when the new priest arrives—’

‘And when might that be, I ask you?’ Ida rolled her eyes.

Someone behind them tutted loudly

‘Perhaps Father Mahon’s going soft in the ’ead like Barmy Dick,’ said Billy.

He was sitting on the other side of Ida and had spent the service alternating between kicking the pew in front and flipping through the hymn books.

Peppered with freckles, with pale blue eyes and russet hair, Billy was supposedly the ‘face of’ Ida’s brother who had died at six after the sulphur used for fumigating bugs had leaked through the brickwork from the house next door and poisoned him. Thankfully, no one queried their carroty cuckoo, so the family didn’t have to explain further.

Like the rest of the family, Billy was kitted out in his Sunday best, which in his case was his new school uniform. To give him growing room, the blazer was much too wide across the shoulders and too long in the arms, which made him look as if he’d put on one of Charlie’s jackets by mistake.

His mother nudged him. ‘Shush!’

‘I only—’

‘Mum, tell him to stop fidgeting,’ murmured Jo, who was sitting beside him. ‘He’s rucking my dress up.’

Jo, who favoured Mattie’s dark colouring, was just sixteen. Despite her blossoming figure she was dressed, as her tender age dictated, in a summer dress with a sash, white ankle socks and the sky blue cardigan Mattie had knitted her for her birthday. However, although Mattie’s younger sister had the face of an angel, she also had a pair of green eyes that could cut you at fifty paces and a mind as crafty as a pixie’s.

Jerimiah, who flanked his family at the end of the pew, cleared his throat and cast his gaze over them, stilling the muttering instantly.

Usually, mass was a predominantly female gathering. Like most of the men of the congregation, Mattie’s father and brother Charlie preferred to spend the one day of the week when they didn’t have to be up at dawn under the blanket for an extra hour or two which meant that while the family were at church, her father, after a welcome lie-in, mucked out the stable, cleaned the harnesses and made sure Samson was fit for another week’s work. However, today he’d left Charlie to do that and, like dozens of others who hardly ever crossed the threshold, he had come to church.

Given that by the time the service finished the whole country would probably be at war with Germany for the second time in a generation, it wasn’t surprising really that the ranks of the faithful had swollen to at least three times its usual size.

‘Laus tibi, Christe,’ muttered Father Mahon.

Mattie crossed herself and stood up with the rest of the congregation.

‘Credo in unum Deum,’ the congregation said in unison.

The double doors at the back of the church burst open and Pat Mead, who owned the paper shop opposite the church, ran in.

‘It’s war!’ he shouted, as he puffed down the aisle.

‘How do you know?’ someone asked.

Pat lumbered to a halt in front of the chancery steps.

‘Chamberlain’s just told us on the wireless ten minutes ago,’ Pat replied, taking a handkerchief from his pocket and mopping his crimson face.

‘Bloody Hitler,’ a man shouted.

‘Bloody politicians, you mean,’ called someone else. ‘It won’t be them going off to fight but our boys.’

A woman started crying as people either fell to their knees or covered their faces with their hands.

Ida clutched Billy to her considerable bosom. ‘Holy Mother, bless and preserve us!’

She crossed herself awkwardly as her son wriggled in her embrace and Mattie and Jo did the same out of habit.

‘What shall we do now?’ asked Jo.

Jerimiah glanced over the heads of the congregation at Father Mahon, who was standing in the pulpit, gazing helplessly down at his distraught congregation with his hands clasped together.

‘Well,’ he said, standing up and stepping out of the pew. ‘As I don’t think the good father will be continuing with mass, we might as well go home.’

‘That’s right,’ said Ida, releasing Billy. ‘You and Charlie can get our indoor refuge kitted out like the Civil Defence pamphlet says while me and the girls get the dinner on.’

Queenie huffed. ‘You hide in your indoors refuge if you like, Ida, but those Hun buggers won’t find me cowering under the stairs when they come.’

Ida and Queenie exchanged their customary acerbic look.

With a sigh, Mattie picked up the gas mask she’d been issued with three months before from the hymn shelf and hooked it over her shoulder. Jo did the same and, with Queenie bringing up the rear, they shuffled out of the row.

Slipping her arm through Jo’s, Mattie and her sister followed their parents down the packed church towards the street outside.

Leading the family from the front like its commander, Jerimiah marched between the closed-up shops in Watney Street Market. As they passed the Lord Nelson they saw that someone had brought a wireless and set it on a table. There was a small crowd of drinkers standing around with their pints in their hands and perplexed looks on their faces.

‘And, until further notice, all theatres, cinemas and similar establishments will be closed as a precaution,’ a plummy BBC announcer informed the gathering.

‘That puts pay to going to the Roxy with the girls next week,’ said Mattie.

‘Furthermore, it is every citizen’s responsibility to observe the blackout and to carry their gas masks at all times,’ continued the presenter, ‘and to ensure they wear a label attached to their person at all times for identification purposes.’

‘I don’t see how a luggage tag tied to my vest will survive if I’m blown to pieces,’ said Jo as they passed Fielding’s the stationers on the corner of Chapman Street and turned into Mafeking Terrace.

Mattie laughed but Ida gave her youngest daughter a hard look.

‘It might be a joke to you, my girl,’ she said, as they reached the end of their street. ‘But some of us remember when the Germans bombed the Isle of Dogs last—’

A piercing wail cut through the air and everyone in the street froze.

‘What is it?’ Jo shouted.

‘Air-raid siren,’ Jerimiah yelled back. ‘We’d better head down to the shelter in Cable St—’

The door of 23 Mafeking Terrace burst open and Mr Potter, the area’s coordinating air-raid patrol warden dashed out.

Cyril Potter was probably in his late fifties with a round apple-like face, short arms and, after thirty years sitting on his backside tallying the accounts in the council’s rates department, a figure like a whipping top. He and his wife Ethel had lived opposite Mattie’s mother and father for years but, unlike the Brogans, they had no children so poured all their parental talents into the local Scouts and Guides. On almost every night of the week either Cyril or Ethel, complete with their respective woggle or wide-brimmed hat, could be seen striding off to their various troupe meetings.

As Hitler couldn’t be bothered to wait until the Civic Defence personnel had been issued with their proper uniform before invading Poland, Cyril had improvised and was wearing his scoutmaster jacket, which was modelled on that of a Boer War officer’s, with the addition of a white ARP armband and a tin hat.

‘Don’t panic! Don’t panic!’ he screamed as he ran up the street as fast as his podgy legs could carry him, banging on doors.

Having reached the top of the street, he crossed the narrow alleyway and did the same down the other side.

Mattie’s neighbours came out, some carrying babes in arms, others tightly clutching toddlers. Some carried blankets and bags containing the picnics the government had instructed people to take with them to the shelter. Since the prime minister had flown to Munich after Hitler invaded Hungary the year before, the whole country had been placed on high alert and the council had been trying to persuade the population to be the same. That said, the promised ground-level air-raid shelter hadn’t yet materialised and although people had been urged to buy Anderson shelters for their back gardens, no one had yet advised the residents of East London who didn’t have back gardens how they should protect their families.

Cyril skidded to a halt in front of them. ‘It’s an air raid!’

‘I know,’ Jerimiah yelled back over the insistent wail.

‘They’ll be here any moment.’

‘I expect so,’ Mattie’s father hollered. ‘Gerry’s not one for hanging about.’

The whites around Cyril’s eyes shone bright for a second then, ripping his helmet off, he threw it aside and pulled the gas mask from its cardboard box. Shoving the moulded rubber over his face, he tore at the webbing until he’d secured it at the back of his head.

‘Get your gas masks on,’ he ordered them, his voice now muffled by the cork filter in the corrugated tubing affixed trunk-like over his nose.

No one moved.

Cyril’s pale eyes regarded them wildly through the insect-like glass disks for a moment, then he spun on his heels.

Screaming something that sounded like ‘Gum-yum-gummom-on,’ he pelted up the street again.

With astonishment and disbelief on their faces, the sea of people parted as the man in charge with seeing them and their loved ones to a place of safety raced between them waving his arms crazily, his sparse hair flapping around his head like a ginger halo.

He’d just got level with number 12 when he turned, swayed for a moment, clutched at his throat, then crumpled onto the cobbles.

There was a moment of stillness, then everyone surged forward. Pushing his way through the crowd, Jerimiah got to him in three strides and pulled off his mask.

Mattie arrived just behind her father and fell to her knees beside the warden. Slipping her hand under his ear, she felt for a pulse as she’d been taught in first-aid classes.

‘Is he dead?’ asked Ida, elbowing her way through.

‘No,’ said Mattie, detecting a faint beat with her fingertips. ‘I think he fainted.’

Turning over the warden’s mask in his massive hands, Mattie’s father flipped open the bottom of the tin filter attached to the tubing.

‘I’m not surprised,’ he said, pulling out the cork within. ‘Silly bugger didn’t take the wax wrapping off and nearly suffocated himself.’

The monotonous wail grating on Mattie’s ear suddenly changed to the two-tone howl of the all-clear. There was a collective sigh from those around them.

‘Praise the saints above,’ said Ida, placing her hand on the crucifix on her chest. ‘It must have been a false alarm.’

‘I suppose we’ll have to get used to it,’ said Mattie, rising to her feet and standing next to her gran.

Queenie took out a roll-up from beneath her Sunday hat and lit it. ‘That we will, child, but it seems that you can be telling Hitler to save himself the trouble of sending his Waffetaffer to put the willies up us.’ She drew on her cigarette and blew smoke upwards. ‘Cos we’ve got our own fecking sirens to do that.’

Chapter Two

THE VICTORIAN IRONWORK glided by as the screech of the brakes brought the nine-thirty from York via Doncaster to a halt alongside platform five of King’s Cross Station. Daniel stood up.

At six one and with a forty-two-inch chest, Daniel didn’t consider himself to be too much above the average man, but after the three-hour journey from York to London, his back and shoulder joints were begging to be released from the confinement of his seat.

Unhooking the leather strapping, he dropped the window down and a gust of cool air rushed in.

Pushing his gold-rimmed glasses up to the bridge of his nose, Daniel took a deep breath.

‘Thank Christ we’ve arrived,’ said the cutlery manufacturer from Sheffield.

The elderly woman next to him, draped in a fox fur stole complete with head and dangling feet, tutted loudly.

The businessman’s eyes flickered over Daniel. ‘Your pardon, Father.’

Daniel smiled. ‘That’s quite alright and it is rather stuffy in here.’

Fortunately Daniel had reserved a seat in First Class, which was just as well as the second and third-class compartments were heaving. Although Britain had only been at war for a week and a day, the whole country was mobilising as the plans the government had been making for almost a year were put into action. The train was packed with members of the armed forces heading for their respective camps and depots. There were so many servicemen crammed into the train that many had been forced to sit on their kitbags in the corridors for the entire journey.

Reaching through the window, the cutlery manufacturer opened the carriage door and left.

‘The air would be much improved if some people had more consideration for others,’ the elderly woman continued, glaring at the general with a chest full of Great War medals sitting opposite.

Clenching his pipe between his teeth, the general got to his feet and, grabbing his attaché case from the rack, blustered out of the carriage.

The two airmen who’d been snoozing beneath their caps since Peterborough sprang up, pulled their kitbags down and pushed their way towards the platform. One stopped at the carriage door and let out a loud wolf whistle which was answered some way away. They laughed and one of them shoved into Daniel.

‘Really, just because there’s a war on, that’s no excuse to forget civilities,’ snapped the older woman as the airman jumped down from the train.

‘Just high spirits,’ Daniel replied, pushing his wire-rimmed spectacles back up his nose.

Reaching up, he took his suitcase from the luggage rack and placed it on his seat, then took down the elderly lady’s portmanteau and placed that alongside his own.

‘Thank you, Father,’ she said. Stepping down from the train, she disappeared into the throng on the platform.

Setting his hat firmly on his head, Daniel picked up his case and also stepped down from the train.

The crowd heading for the ticket barrier was awash with khaki, navy and air force blue, while the passengers surging down the platform to board the train were mostly less than three feet tall. They all had luggage labels tied to their coats and many were clutching teddies or raggedy dolls.

Mingled amongst the evacuees were mothers with too-bright smiles and jolly members of the Women’s Voluntary Service, distinctive in their green coats and hats. Behind the great swell of children being sent out of harm’s way was huddled a group of women who were either heavily pregnant or carrying tiny infants in their arms. For most their only experience of life outside London was a yearly trip to the seaside, so no wonder they looked desolate as they contemplated leaving their kith and kin for a stranger’s hospitality.

Side-stepping several prams, Daniel walked through the steam bellowing from the stationary engine and, smiling gently as he passed the mass of scared, tearful children, he headed towards the exit. As he reached the end of the platform, a little girl of about four or five, with bright golden curls and wearing an oversized coat, dropped her golliwog. She screamed but her voice was lost in the echoing noise of a hundred other children, the hiss and clatter of the trains and the Tannoy announcements.

In two strides Daniel crossed the space and scooped the soft toy from the platform, then sprinted after the child.

‘Excuse me,’ he said, stepping in front of the two women and holding up the golly. ‘I think you’ve left someone behind.’

‘Mr Bobby,’ the small girl shouted, stretching up for her precious toy.

Daniel handed her the golly, then hunkered down in front of her. ‘If he’s Mr Bobby, what’s your name?’

The little girl hugged her golly and stuck her thumb in her mouth.

‘Go on, tell the father,’ said her mother, a blonde woman in her mid-twenties and dressed in a navy maternity dress with flat pumps.

‘Gladys,’ mumbled the child over her thumb.

‘Well, Gladys, you need to keep an extra tight hold on him so he doesn’t get lost again,’ said Daniel. ‘Can you do that?’

Gladys nodded and Daniel straightened up.

‘Thank you so much,’ said Gladys’ mother, gazing in wide-eyed wonder up at him.

‘My pleasure.’ Daniel raised his hat and continued along the platform.

Handing his ticket to the collector, he made his way to the left luggage office. Glancing up at the arrivals board, he noticed that the 2 o’clock from Cambridge had just arrived so he waited a few moments until the passengers spilled out into the concourse, then pushed open the half-glazed door and walked into the office. As usual, the place was packed to the gunnels with impatient travellers.

Daniel joined the back of the collection queue as passengers from the Cambridge train surged in. After about twenty minutes of shuffling forward and a frantic search for a missing hatbox for a very distraught bride-to-be, Daniel stepped up to the mahogany counter.

‘Good afternoon,’ he said, smiling courteously. ‘I left a bag in number 35 about four weeks ago.’

‘I shall need a ticket, Father,’ the clerk grunted.

‘Of course,’ said Daniel, putting his hand in his breast pocket. ‘I have it here somewhere.’

He ferreted around for a minute or two, then shoved his hands in his side pockets. ‘I know I pulled it out ready as we pulled into the station so it must be . . .’

Behind him people started grumbling and tutting.

He pulled his wallet from his inside pocket. ‘I can’t think where it could be.’

Mutters of ‘get a move on’ started behind.

Daniel returned to his pockets. ‘I’m sure I have it here somewhere,’ he said, depositing his handkerchief, half a packet of Fruit Pastilles, a rosary and penknife on the desk.

He rummaged a bit more, then turned to the people behind him. ‘I’m so terribly sorry. I was sure I’d put my ticket in a safe place—’

‘For gawd’s sake,’ shouted a man in a cloth cap from the back. ‘Give him his bag.’

The clerk, who was now quite red in the face, drew a deep breath. ‘The rules state that I have to have a ticket before—’

‘Sod the bloody rules,’ shouted someone else.

‘Yeah, I’ve got a ruddy train to catch,’ called another.

‘He’s only doing his job,’ said Daniel as the door opened and more people pressed in.

‘He’s right. I’m only doing my job and he could be anyone,’ said the beleaguered clerk. ‘He could even be a Nazi.’

The office erupted in laughter.

‘Ain’t you got eyes?’ asked the man in the cloth cap again. ‘He’s wearing a dog collar not a bloody swastika. Now, unless you want us all to suffocate, do us a favour and let him have his bag.’

The clerk threw his hands up and disappeared through the door behind him.

Daniel smiled at his audience.

‘I am so sorry,’ he repeated, repositioning his spectacles again.

As the end of the drama was in sight, the sea of faces had changed from irritation to indulgence.

‘It’s all right, Father,’ said a middle-aged woman at the back, and others muttered their agreement.

The clerk returned with an expensive-looking caramel-coloured leather suitcase with contrasting dark-brown corners, thickset clasps and DJMC stamped in gold letters above the handle.

‘There you go,’ said the clerk sliding it over the counter to him. ‘Rules and regulations, but as you’re a man of the cloth . . .’

Clasping the handle, Daniel took it from him. ‘I’m much obliged to you and apologies for causing you so much trouble.’

The clerk smiled. ‘Don’t mention it.’ He glanced at the dangling label. ‘And you have a nice evening, Father McCree.’

Daniel drained the last of his over-stewed tea. Placing the cup back in its saucer, he smiled.

‘Well, Mrs Dunn, I can honestly say that’s the most welcome cup of tea I’ve had for a very long time,’ he said, offering her the cup.

It was now just a shade before eleven and the day after he’d arrived in London. Having booked himself into a modest hotel around the corner from the station, Daniel had gone to a nearby restaurant and treated himself to beef stew and dumplings for supper, followed by jam roly-poly and custard before returning to the hotel and collapsing into bed. Even though the mattress was a little on the lumpy side, he’d fallen asleep the moment his head hit the pillow, waking only when the breakfast gong sounded at seven.

It had taken him an hour and a half to undertake the forty-minute journey to his destination due to a points failure at Moorgate station, which had left them stranded in the carriage for almost half an hour before the train moved off. He’d finally reached Stepney Green Station at ten-fifteen and it had taken him a brisk twenty minutes’ walk to reach St Brendan and St Bridget’s church and rectory.

The rectory was a double-fronted Victorian house that sat incongruously amongst the huddled two-up two-down workmans’ cottages around it. The decor he’d seen so far was tired and faded, but the windows sparkled and a faint smell of beeswax was evidence of the housekeeper’s diligence with the duster.

The room he was now in was the smaller of the two front rooms and in times past had been the lady of the house’s morning room. Sitting opposite him in an upholstered easy chair was Father Mahon, the long-serving priest who he had come to assist in his parish duties. Although Daniel couldn’t be sure, he’d put a pound to a penny that Father Mahon was nearer to eighty than seventy. The old man’s closely cropped white hair was so sparse that from a distance he looked completely bald, and he was so stooped that the top of his head barely reached Daniel’s shoulder. Daniel was therefore surprised that, when he offered his hand in greeting, the good father’s grip was that of a man half his age. He also noticed that Father Mahon’s coal-black eyes, although surrounded by finely etched lines and wrinkles, were both focused and sharp as they held Daniel’s gaze.

‘Can I get you another, Father?’ the housekeeper asked.

Unlike the rector, who looked as if a strong wind could carry him away, Mrs Dunn his housekeeper looked like an Irish hurling striker in a wraparound apron.

‘No, I’m fine, thank you,’ Daniel replied.

‘Or perhaps another piece of cake?’ persisted Mrs Dunn.

‘No, honestly.’ Daniel patted his stomach. ‘St Peter himself would have trouble saying no to such a morsel but, if I’m to do justice to the fish pie you’ve promised me for lunch, I need to keep space free. Father Mahon assures me your cooking is delicious.’

The housekeeper shot the elderly priest sitting opposite Daniel a hard look. ‘And sure how would he know.’

‘Soft now, Mrs Dunn,’ said Father Mahon. ‘You don’t want to be scaring the lad on his first day with us.’

Not sure at twenty-eight if he still qualified as a ‘lad’, Daniel pushed his spectacles back up his nose and smiled politely.

‘By that I suppose you mean I should be happy to see you waste away,’ Mrs Dunn scolded. ‘As the Good Lord is my witness, Father, himself barely eats enough to keep the breath in his body.’

The priest sighed. ‘A man shall not live by bread alone, Mrs Dunn.’

‘Nor by the stews, pies or pot roast I put before you either, it would seem,’ she replied, taking the priest’s cup from him and slamming it on the tea trolley. ‘Still,’ she smiled sweetly at Daniel, ‘at least now you’ve come to join us, Father McCree, there will be someone in the house who will appreciate my hard work in the kitchen. And don’t worry, Father.’ She nodded at Daniel’s luggage by the ancient bureau. ‘I’ll send Alf to carry your things to your room when he’s finished stoking the boiler and I’ll be serving dinner at one.’

Wheeling the squeaky trolley with the used crockery rattling on it, she left the room.

‘You must forgive her,’ said Father Mahon as the door clicked shut. ‘She’s a good woman, none better, but after nigh on thirty years of ordering poor Paddy about, God love and rest him, she has yet to break the habit.’

‘Please, there’s no need at all to be apologising, Father,’ said Daniel.

The old priest cocked his head to one side and regarded Daniel curiously. ‘Where is it in Ireland you said you were from?’

Pulling the handkerchief from his top pocket and taking off his glasses, he replied,

‘Donegal. My family lived in Meetinghouse Street across from the castle. Do you know it?’ He made a play of polishing the lenses.

The old priest smiled and shook his head. ‘I’m a Cork man meself from Kinsale but I just thought I heard a bit of Limerick in you.’

Daniel smiled but didn’t reply.

Father Mahon sighed. ‘Well, anyhow, in these uncertain times the flock is in great need of practical as well as spiritual guidance so, if you come from the moon, I’m glad to see you.’

‘We are in testing times, to be sure,’ said Daniel, happy to move away from his accent. ‘And I’m wild keen to get started.’

‘So the bishop’s letter states,’ said Father Mahon. ‘In fact, he writes about you in glowing terms and you shouldn’t have the trouble my last assistant had. Poor boy. Father Frobisher, a godly man, you understand, and fired with enthusiasm, was the fourth son of some minor aristocrat or another and spoke like a BBC announcer so you can imagine how well he went down around here. But I’m sure you’ll get on marvellously, although your waistline will suffer for it.’

A wry smile lifted the corner of Daniel’s mouth. ‘I’ll be sure to guard against falling into the sin of gluttony.’

‘There is one thing about the bishop’s letter commending you to the parish that I’m perplexed about. The bishop stipulates you’re not to undertake mass or take confession.’

‘Yes, I know that’s unusual but it’s part of a penance he’s laid on me.’ Clasping his hands together, Daniel bowed his head. ‘I’m afraid to say it dates back to my time in—’

‘Whatever it is, it is between you and God, lad,’ interrupted the older man. ‘It’s of no matter and of no mind to me.’

Daniel raised his head. ‘Thank you, Father.’

‘And although it might be difficult for you to imagine now, Father McCree—’ Father Mahon’s eyes twinkled mischievously – ‘but I was a young lad like yourself once upon a time and I know well the temptations of such an age.’

There was a knock.

‘Come!’ shouted Father Mahon.

The door opened and an elderly man wearing baggy light brown overalls, a roll-up dangling from his mouth, shuffled into the room.

‘Mrs D tells me you want somefink shifted upstairs,’ he said.

‘Yes, Father McCree’s belongings, if you don’t mind, Alf,’ said Father Mahon.

The handyman lumbered towards Daniel’s luggage over by the window but Daniel beat him to it.

‘If you take the larger one, I can manage this one,’ he said, grasping the handle of the tan case he’d collected at King’s Cross.

‘Right you are, guv,’ said Alf, lifting Daniel’s battered old case with the P&O and White Star passenger label stuck on the side. ‘You’re at the top of the house at the back.’

He left.

Father Mahon got to his feet and looked at Daniel. ‘There’s an hour or so before lunch so why don’t you settle in and we can talk more then.’

Daniel thrust out his hand but the rector raised a scraggly eyebrow.

Returning his case to the floor, Daniel knelt in front of the old man and, clasping his hands together in front of him, bowed his head.

Father Mahon placed his slender white hands lightly on Daniel’s dark-brown hair.

‘Actiones nostras, quaesumus Domine,’ muttered the rector.