Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Serie: The Stepney Girls

- Sprache: Englisch

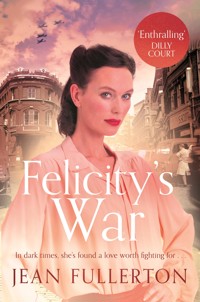

'An enthralling page-turner' DILLY COURT 'A heart-warming WW2 love story' ROSIE GOODWIN 'A great new series from the queen of East End sagas' ELAINE EVEREST * 1941. Whilst London is battered by air raids, Felicity "Fliss" Carmichael has troubles of her own. Still reeling from catching her fiancé cheating, she flees to her childhood home at St. Winifred's Rectory, reuniting with her sister Prue and Hester Katz, a Jewish doctor sheltering there. Though heartbroken, Fliss finds purpose again as a journalist. On assignment, she crosses paths with Detective Inspector Timothy Wallace, who shares her passion for truth and justice - though not her political beliefs. Despite their differences, an instant spark ignites between them. But their love faces twists and turns ahead. While Fliss stumbles upon a crime and bravely intervenes, Tim's investigation into black market racketeering puts him in mortal danger... In a city under siege, Fliss and Tim forge an unlikely bond. But can their blossoming romance endure the perils ahead?

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 504

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Felicity’s War

Jean Fullerton is the author of twenty historical novels and a memoir, A Child of the East End. She is a qualified District and Queen’s nurse who has spent most of her working life in the East End of London, first as a Sister in charge of a team, and then as a District Nurse tutor. She is also a qualified teacher and spent twelve years lecturing on community nursing studies at a London university. She now writes full time.

Find out more at www.jeanfullerton.com

Also by Jean Fullerton

East End Nolan Family

No Cure for Love

A Glimpse at Happiness

Perhaps Tomorrow

Hold on to Hope

Nurse Millie and Connie

Call Nurse Millie

All Change for Nurse Millie

Christmas With Nurse Millie

Fetch Nurse Connie

Easter With Nurse Millie

Wedding Bells for Nurse Connie

East End Ration Book

A Ration Book Dream

A Ration Book Christmas

A Ration Book Childhood

A Ration Book Wedding

A Ration Book Daughter

A Ration Book Christmas Kiss

A Ration Book Christmas Broadcast

A Ration Book Victory

Stepney Girls

A Stepney Girl’s Secret

A Stepney Girl’s Christmas

Novels

The Rector’s Daughter

Non-fiction

A Child of the East End

First published in paperback in Great Britain in 2024 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Jean Fullerton, 2024

The moral right of Jean Fullerton to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

No part of this book may be used in any manner in the learning, training or development of generative artificial intelligence technologies (including but not limited to machine learning models and large language models (LLMs)), whether by data scraping, data mining or use in any way to create or form a part of data sets or in any other way.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN: 978 1 83895 761 2

E-book ISBN: 978 1 83895 762 9

Printed in Great Britain.

Corvus

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

To my three daughters: Janet, Fiona and Amy

Chapter one

AS GILES TURNED his burgundy-coloured Morris Eight into Wilton Road, Felicity Carmichael leaned forward and gathered up her handbag and umbrella from the footwell.

‘You know, you really don’t have to drop me at the station, Giles,’ she said, as they trundled along the road. ‘Victoria’s only just over a twenty-minute walk from the flat.’

‘I know, darling,’ said Giles, briefly taking his eyes off the road to smile at her, ‘but with so much rubble in the street I don’t want you to twist your ankle or something along the way.’

He was right. After the Luftwaffe’s six-hour visit the night before, you could barely see the tarmac outside their flat on St George’s Drive for the chunks of brickwork, glass and personal possessions strewn across the road. Although the all-clear had sounded four hours ago, the ARP heavy rescue and Red Cross volunteers were still busy: digging out basements and bandaging heads respectively.

It was just after seven thirty in the morning on the first Tuesday in February 1941 and Felicity, or Fliss as she preferred to be called, was sitting in the front seat of her fiancé’s car.

‘Plus,’ continued Giles, pausing to let a line of school children carrying their satchels and gas masks cross the road, ‘the North London Women’s Co-operative Conference is very important, so I want to make sure my best reporter is there to get a scoop before the Workers’ Life or the Daily Worker.’

Fliss smiled. She didn’t need Giles to remind her that the conference was important. And it was for that reason Fliss had forgone her usual slacks and box-shoulder jacket and instead picked her navy suit and cream blouse out of the wardrobe that morning.

Despite the hard frost covering the rooftops of the Edwardian terraces on either side of the road, she felt a little warm glow in her chest at Giles’s unexpected praise.

Suave and eloquent, Giles Cuthbert Naylor was halfway to his thirty-first birthday. With a lean physique, high broad forehead and straight aquiline nose, he was handsome in a rather cool and collected way. However, although he always said his height was five feet eleven, in truth, he was just over five nine and a half. As Fliss was only two inches shorter, out of consideration, since they’d become a couple, she wore low-heeled shoes. Having been sent down from Oxford after the university’s Communist Society fought a pitched battle with the university’s British Union of Fascists, Giles was a hero of the Socialist League.

Much to the disgust of her mother, Fliss had joined the Socialist League herself while at a Luton secretarial college, and she knew of Giles Naylor by repute before she actually met him.

After working for two years as a junior reporter at the Bedfordshire Times and Independent, reporting on WI meetings and village fetes – certainly not activities in the vanguard of the socialist revolution – Fliss had answered an advertisement for a reporter on the Workers’ Clarion. Having got the job – and again, much to her mother’s irritation – she had moved to London. She’d only been working at the Clarion for a few months when Giles joined as the senior editor.

As the last school child stepped onto the pavement, Giles let go of the clutch and pressed his foot down on the accelerator. But as the sandstone edifices of Victoria station came into view, Fliss yawned.

‘Tired?’ he asked.

Fliss nodded. ‘Well, it was after midnight before the gang left.’

He raised his eyebrows. ‘Was it? I can’t say I noticed.’

The gang were a motley bunch of intellectuals and academics Giles had allied himself with, all of whom – like him – were fervently committed to the establishment of a socialist state. Exactly how this was to be achieved was something they had yet to agree on. After thrashing out the finer points of socialist revolutionary doctrine while consuming a dozen bottles of pale ale and several portions of fish and chips from the fish bar on Vauxhall Bridge Road, they had finally said their goodbyes at half past midnight.

Unfortunately, as usual, they’d left the empty bottles and screwed-up greasy newspaper behind, and it had taken Fliss another half-hour to clear away the mess before falling into bed beside Giles, who had started snoring as soon as his head hit the pillow.

Pulling up alongside the station, Giles yanked on the brake then turned in his seat to face her.

‘Well, here we are,’ he said, resting his right hand lightly on the steering wheel. ‘Are you all set?’

‘I think so,’ Fliss replied, opening her handbag to check her notepad and pen yet again.

‘I don’t want you to be nervous, Fliss,’ he said, his grey-green eyes looking earnestly at her, ‘but the cream of the Labour Party’s intelligentsia will be on the platform today, including one of Labour’s big hitters Jennie Lee, which I’m sure you girls in the audience will be thrilled about, although I wouldn’t hold your breath for any cake recipes or knitting tips: by all accounts she’s a bit of a bluestocking. Even so, the Party’s Central Committee sent her as the main speaker, so you will really have to get down everything she says.’

Fliss raised an eyebrow. ‘Who came top in the Pitman shorthand class?’

He laughed. ‘I’m sorry. It’s just—’

‘I know,’ Fliss cut in, placing her hand on his tweed sleeve. ‘The Fleet Street press will be there, and you want to make sure a small newspaper like the Clarion doesn’t get squeezed out.’

He laughed. ‘You know me so well.’

‘I should think so, after four years,’ she replied.

Strictly speaking, Giles wasn’t her fiancé. And not because he didn’t love her. Because he did. Just as much as she loved him. But Giles believed that marriage was an institution imposed on workers as part of the capitalist system, so wouldn’t subscribe to it out of principle.

Anyway, what did it matter that she didn’t have a ring on her finger or a piece of paper? She and Giles were as married as any man and woman in the land.

‘So don’t worry, I’ll be sure to get every speech and answer to a question down, word for word,’ Fliss promised. ‘And I’ll do my very best to bag one of the platform speakers for an in-depth interview.’

Giles winked. ‘Just wriggle past a couple of the old fogeys from the National Executive Council and flutter your eyelashes. I’m sure you’ll have them eating out of the palm of your hand.’

Annoyance niggled in Fliss’s chest. ‘I would hope, Giles, that they would be willing to talk to me about their vision of a democratic socialist society because I’m a serious journalist.’

‘Of course they will, sweetheart,’ Giles replied, giving her an adoring look. ‘But would it hurt to use your feminine wiles to persuade them?’

Frowning slightly, Fliss didn’t reply.

‘Come on, Fliss, don’t be a sourpuss.’ Giles’s lean face formed itself into a scolded-puppy expression.

Fliss studied him for a moment.

‘So, are you going into the office today?’ she asked, forcing her irritation aside and putting on a smile.

He nodded. ‘I’ve got a pile of reports to read from the central committee. Not to mention sorting out the next edition.’

‘Well, the conference doesn’t finish until six,’ said Fliss, ‘so I can’t see me getting back to the flat much before seven thirty at the earliest. I hope you don’t mind a late supper.’

‘I’ll tell you what,’ said Giles, ‘why don’t we eat out? To celebrate your scoop interview.’

‘You’re putting the cart in front of the horse, aren’t you?’ laughed Prue. ‘I haven’t got one yet.’

‘Well, I have every faith that you will, my darling.’ He took her hand, raising it to his lips. ‘Every faith.’

They exchanged fond looks then, turning, Fliss grabbed the passenger-door handle.

‘Oh, before you go, I don’t suppose you’ve got a couple of bob I could have?’ Giles asked as she opened the door.

Fliss looked over her shoulder.

‘Just for a bit of petrol,’ he added, his scolded-puppy face returning. ‘I’m running on fumes.’

Fliss glanced at the fuel dial. Sure enough, its needle was hovering below E.

‘I wouldn’t ask,’ he continued, ‘but with articles and reports piling up on my desk, I won’t have time to get to the bank until this afternoon.’

Letting go of the handle, Fliss unclipped her handbag, took out her purse and opened it.

‘You’re a darling,’ he said, as he lifted the solitary brown ten-shilling note from her purse.

Tucking it in his inside breast pocket, Giles slid his hand along the back of her seat and drew her into an embrace.

‘What would I do without you?’ he said, looking deeply into her eyes, then pressing his lips onto hers.

‘I ought to go,’ she said reluctantly as their kiss ended.

‘Yes, you should,’ he agreed, giving her a smouldering look. ‘Before I forget all about the North London Co-Operative Women’s Conference and the mountain of paperwork on my desk and drive straight back to the flat so we can spend the rest of the day in bed.’

Fliss’s heart did a little double step. Then, remembering how she’d spent days persuading Giles that she could carry out such a big assignment, she disengaged herself from his arms.

Grasping the handle again, she opened the door, chilling the car’s interior in an instant.

‘I’ll see you this evening,’ she said, swinging her legs out of the car.

Giles blew her a kiss and Fliss slammed the door.

She stood on the frost-whitened pavement and watched the Morris Eight pull away from the kerb and join the traffic heading up Buckingham Palace Road.

Turning towards the station, where sandbags were stacked to the lead canopy to protect the Southern Railway’s office windows, Fliss joined the crowds of suited office employees and khaki-uniformed army personal crunching through icy puddles as they streamed through the entrance.

‘So finally, Miss Lee, at the next election, whenever that is, are you hoping to see more women as MPs?’ Fliss asked the dark-haired women with rather pronounced eyebrows standing before her.

It was just after one o’clock. Having swiftly downed a fish-paste sandwich with curling corners from the buffet, plus a lukewarm cup of tea, Fliss was now standing in the refectory of The North London Collegiate School. Surrounding her were the other hundred and fifty conference attendees and a cacophony of women’s voices.

‘I cannae deny that there is a sore lack of female representation on the green benches of Parliament,’ the one-time parliamentary member for North Lanarkshire replied. ‘But people should vote for policies, not the sex of the candidate. However, as we have seen in the Soviet Union – where women take their place alongside men in all parts of society – only true socialism will allow women to be fully equal in all aspect of political and social life. Now, if you’d be kind enough to excuse me …’

‘Of course,’ said Fliss, closing her notebook. ‘You must have hundreds of people wanting to speak to you.’

Giving her an enigmatic smile, the Independent Labour Party’s leading light turned and walked away.

‘Who’s the cat that’s got the cream, then?’

Fliss turned and found her friend and fellow Westminster Labour Party member, Ruth Mellows, standing behind her with two mugs of tea.

Standing six inches shorter than Fliss at five foot one and five years older, Ruth was a second-generation Irish redhead with a liberal sprinkling of snowflake-sized freckles all over her face.

‘Giles will be impressed,’ Ruth went on, looking quite impressed herself as she offered Fliss one of the mugs.

Tucking her notepad and pen into her handbag, Fliss took the hot drink.

‘Yes, I am feeling a little pleased with myself,’ she replied. ‘Hopefully an interview with such a well-known Labour Party figure will boost the Workers’ Clarion sales.’

‘And stop this government banning the Workers’ Clarion like they did the Daily Worker in January,’ added Ruth.

‘I don’t think we’re in danger of being closed,’ said Fliss. ‘After all, the Clarion follows the official Socialist League and Labour Party line in supporting the National Government.’

‘Even so,’ Ruth took a sip of tea, ‘we have to be vigilant against the capitalist system protecting itself by suppressing workers.’

There was a sudden movement in the crowd, who had all started towards the refectory entrance.

‘Looks like they’re getting ready to begin the afternoon session.’ Fliss swallowed a large mouthful of tea. ‘We’d better take our seats.’

‘I’ve got to spend a penny,’ said Ruth, handing her mug to Fliss. ‘Can you take my drink for me?’

Her friend hurried off and Fliss joined the throng of women making their way back into the main hall. She took her seat at the end of a row and put her handbag on the chair beside her.

The afternoon speakers began to file on to the stage as the final few members of the audience took their seats, Ruth among them.

‘You’d think they would have found a venue with more than three blooming ladies’ toilets, wouldn’t you?’ she whispered, as Fliss swung her knees aside to let her past.

Mrs Gilmore, the full-bosomed, grey-haired Londonwide chairwomen for the Women’s Co-operative Society took her place at the podium and the low murmur of voices subsided.

‘Welcome back, ladies,’ she said, casting her close-set eyes over the assembled room. ‘This afternoon it is my great delight—’

The main doors at the back of the hall burst open and heavy boots echoed around the high ceiling. Every woman in the hall turned to see what the commotion was and found half a dozen police officers in helmets and two army officers with their caps tucked under their arms marching down the central aisle. The police officers stationed themselves, evenly spaced, at the end of the rows while the officers climbed onto the stage.

‘What is the meaning of this?’ snapped Mrs Gilmore, a mottled flush creeping up her double chin as she glared at the two officers who halted alongside her.

‘I’m afraid, ladies, you will have to vacate the premises immediately,’ said the taller officer with greying hair and a pencil moustache.

‘We will not, Officer,’ spluttered the outraged chairwoman. ‘We’re holding a legitimate public meeting, and your attempt to disband that is an infringement of our democratic rights and a suppression of free speech.’ Her nostrils flared like a winded horse as she drew in a deep breath. ‘You may not agree with our politics but—’

‘If I could just stop you there, madam,’ cut in the moustachioed officer, holding up his hand. ‘I don’t care one jot what your politics are and neither does the thousand-ton unexploded German bomb that has tunnelled its way under the office block next door, which might be ticking down its last few minutes before sending the whole bally lot of you to Kingdom—’

There was a scrape of chairs as the audience, including Fliss, rose as one.

‘So would you mind making your way out in an orderly fashion?’ continued the officer, shouting over the squeal of voices and shifting furniture.

Hooking her handbag over her arm, Fliss, with Ruth a step or two behind her, hurried towards the main entrance at the rear of the hall.

‘I suppose I ought to head back to work,’ said Ruth with a sign of resignation as they arrived on the other side of the rope cordon, its triangular yellow flags fluttering in the chilly breeze. ‘There’s no point losing half a day’s money. What about you?’

‘I’m not sure,’ said Fliss, thankful she had bagged the scoop Giles wanted for the Clarion before the Luftwaffe interfered. ‘To be honest, we had half the Pimlico Independent Labour Party around last night, so I could do with a spare couple of hours to tidy the flat. I know Giles is up to his eyes at the office, so perhaps I’ll ring him and see what he wants me to do.’

‘Will I see you at the Crown on Saturday?’

‘I expect so,’ said Fliss, without any real enthusiasm.

The Crown was, in fact, the Crown Tavern in Clerkenwell, where it is reputed that Lenin and Stalin first met. It was also where many of their London followers met each weekend to plan the revolution while downing half their body weight in pale ale. As women were outnumbered some four to one at these radical gatherings, Fliss often found herself studying the nicotine-stained wallpaper while sipping her G&T.

Hugging Ruth briefly, Fliss waved her off and headed back towards Edgware station. Spotting a telephone box on the other side of the road, she crossed over and pulled open the door, the usual smell of ammonia and tobacco wafting over her as she stepped in. Resting her bag on the shelf, Fliss rummaged in her purse for a few coppers then picked up the black Bakelite receiver and placed it to her ear. There was a pause then a click at the other end.

‘Operator. What number do you require?’

‘Bloomsbury three four seven, please,’ Fliss replied.

There was another pause and the operator spoke again. ‘Putting you through.’

The pips sounded at the other end and Fliss pressed two thruppenny bits into the slot next to the A button.

‘Workers’ Clarion,’ barked the gruff voice of Jim, the Clarion’s trade union reporter.

Fliss frowned. ‘Jim?’

‘Oh, it’s you, Fliss,’ he replied. ‘Sorry, but the damn phone hasn’t stopped all afternoon.’

‘Isn’t Gwen there?’

‘Naw,’ Jim replied. ‘Got a headache before lunch and Giles sent her ’ome.’

‘Poor Gwen,’ said Fliss, an image of the newspaper’s curvy blonde receptionist flashing briefly into her mind. ‘Can I speak to Giles?’

‘’Fraid not,’ Jim replied. ‘He got a telephone call an hour ago about some strike or something and dashed out to cover it. Can I help?’

‘Not really,’ Fliss said, and explained about the conference’s sudden end.

‘Well, there’s nothing to do here,’ said Jim. ‘You might as well call it a day and go home.’

‘Perhaps I will,’ Fliss replied. ‘I’ll see you tomorrow.’

Returning the receiver to its cradle, Fliss pressed the B button and one of the thruppenny bits rolled out of the slot beneath. Pocketing the unused coin, she pushed open the booth door and stepped out.

Having made the twenty-five-minute walk from Victoria station, Fliss turned into Warwick Square and its elegantly proportioned Edwardian townhouses just after three thirty.

When she’d moved down to London from rural Bedfordshire some four years ago, spending the odd quiet hour reading in the arboreal oasis of the central park had helped Fliss adjust to life away from fields and woodland. But now the park, like everywhere else, had been given over to the war effort. The neat shrubs and colourful flowerbeds had been dug up, and now sprouted spring cabbage and the first feathery leaves of carrots.

Passing the white wooden shed that was the Warden’s Post, Fliss turned into St George’s Drive and kept walking until she reached the last-but-one house where she and Giles occupied the top-floor flat.

Climbing the three steps to the front door, Fliss pushed it open, dislodging a few flakes of its peeling green paint as she stepped inside.

The grand Edwardian family house’s hallway was now the ground-floor lobby for the six flats that the four-storey house had been divided into.

Grasping the handrail, Fliss made her way upstairs to her flat – which was in the old servants’ quarters. Stopping in front of the door, she dived into her bag, pulled out the key and let herself in.

The flat was small, not much more than two main rooms and a bathroom. The kitchen, if you could call it that, had a butler sink, with a cold tap, a sloping draining board on one side and an ancient stove on the other.

As she closed the door behind her, surprise widened Fliss’s tired eyes. Instead of the plates and glasses from the previous night being piled high in the sink, as they had been when she left that morning, they were now stacked in the bright-yellow dresser next to the stove. In addition, the four kitchen chairs had been returned to their rightful places and were tucked around the kitchen table.

Casting her gaze across to the lounge area, she noticed that the two lime-green armchairs had been set straight and the cushions on the tan-coloured leather chesterfield had been plumped and set at angles.

Confused, Fliss stared at the tidy living area for a moment.

Then she heard a noise coming from behind the closed bedroom door.

Frowning, she walked across the Turkish rug – it had been swept, she noticed – and, opening the door, was confronted by a pair of undulating bare buttocks with a pair of feet with painted toenails wrapped around them.

Fliss stared incredulously for a second or two, then found her voice. ‘Giles!’

A woman screamed, and Giles jumped onto his knees with his hands covering his privates. Gwen, who had clearly got over her headache, squirmed beside him, clutching the sheets over her still-heaving chest.

Red-faced and sweating, Giles stared wordlessly at Fliss for a moment, before he raised his right hand. ‘Now, Fliss, this is not what it looks like.’

Chapter two

WITH HIS BREATH visible in the freezing February air, Detective Inspector Timothy Wallace studied number forty-three Malmsbury Road in Bow from beneath the brim of his fedora.

‘Do you think they’ll be out soon?’ asked Alex Lennox, Tim’s detective sergeant, who was standing just behind him.

Alex, who at twenty-six was four years Tim’s junior and an inch or two shorter, was dark-haired and green-eyed, with the physique of an athlete. Whereas Tim had run the streets of East London as a barefoot child, Alex was the son of a country schoolmaster at a boys’ school in Leyton Buzzard, and had never left Buckinghamshire until joining the Metropolitan Police Force a day after his twenty-first birthday. However, after a brief spell pounding the beat in Kilburn and passing his sergeant’s exam, he’d been transferred to Wapping CID. Although he’d tried to sign up to fight a few days after war broke out, the medical officer discovered he had a very slight curvature in his neck and returned him to his post in Wapping. Intelligent and intuitive, Alex was shaping up nicely as a detective, so the army’s loss was the Met’s gain, as far as Tim was concerned.

‘Depends on what they find,’ Tim replied, without taking his eyes from the four-storey terraced house across the street.

It was close to eight o’clock in the evening, and he, Alex and Constable Bellman were standing in the airy – the below-pavement area that would once have been the servants’ entrance – opposite the house.

‘I wish they’d blooming well ’urry up,’ grumbled Eric Bellman. ‘My plates of meat are like blocks of ice.’

Eric, a squarely built chap with thinning blond hair, was a war reserve constable. At forty-three he was too old to be called up, but had opted to swap his desk in the rates department of Poplar Town Hall for something more exciting and more lucrative – by two pounds and five shillings a week.

Thanks to the thousand-ton bomb that had landed on the street beyond in the previous night’s air raid, the house in question had square black holes instead of windows, through which tattered curtains flapped. It had fared better than some of the hundred-and fifty-year-old houses further along, which had collapsed in on themselves like a pack of cards. Like so many East Enders, the families of Malmsbury Road had returned after a night in an air raid shelter that morning to find their homes destroyed and their possessions blown into the street. However, because of the danger of collapse, until the rescue team had finished checking the walls and floors, the families hadn’t yet been allowed to return. It was for that reason that Tim and Alex, along with a small contingent of uniformed constables, had been standing in the airy at number thirty-eight for the best part of three-quarters of an hour.

‘Suppose we ought to be grateful the air raid siren ain’t gone off yet,’ Eric continued, ‘as the fog on the riv—’

Tim’s raised hand stopped him mid-word as a light flickered through the empty door frame. He gave a low whistle through his teeth, which was answered by another from his right.

A couple of moments went by then the bulky figure of Chalky White, heavy rescue leader, lumbered out with five men close behind.

Straightening up to his full six foot one, Tim glanced across the low wall to find Constable Ted Tyler, a regular like himself, and constables Lambton and Rowland standing ready in the airy of number forty, next door.

He and Ted exchanged nods and then all six officers started up the stone stairs.

‘All right, Chalky,’ Tim called, shining his muted torch on the cobbles as he strolled across.

The burly boss of Green Team gave a hard laugh. ‘Wallace. Bit chilly for an evening stroll, isn’t it?’

‘Inspector Wallace, if you don’t mind,’ Tim replied, coming to a halt just in front of him. ‘And we’re out because we’ve been receiving reports of looting.’

In the dim light from the police torches, an innocent look spread across Chalky’s heavy features. ‘Have you?’

‘We have,’ Tim replied. ‘Often just after you and your lads have been in.’

A belligerent expression replaced Chalky’s ingenuous one in an instant. ‘I hope you’re not—’

‘Search ’em, boys,’ snapped Tim, and the officers standing behind him surged forward.

As each of the men under his command tackled one of the heavy rescue team, Tim held out his hand. ‘Give it over, Chalky,’ he said, indicating the heavy canvas tool bag in his hand.

Adjusting his grip on the handle, Chalky’s face screwed into a hateful glare.

‘Now!’ barked Tim.

Chalky hesitated for a moment longer, then shoved the bag at him. Tim placed it on the pavement between them, pulled it open and shone his torch on the contents.

The beam of Tim’s torch highlighted a carriage clock, cutlery and a mother-of-pearl dressing-table set on top of the usual collection of tools.

He looked up. ‘Empty your pockets and drop it into the bag.’

Chalky glared at him for a moment then, shoving his hands into the deep pockets of his navy overall, pulled out a string of pearls, two rings, a wallet and a watch on a chain.

‘What you got, lads?’ asked Tim, his hard gaze fixed on the man in front of him.

‘A couple of purses and some jewellery,’ Alex replied, after frisking one of the team.

‘A canteen of cutlery and some old-fashioned silver photo frames,’ Ted called across, holding up a faded sepia photograph of an elderly couple.

The other officers listed knick-knacks, more jewellery and watches, as well as a pair of leather gloves, a pack of baby’s towelling nappies and a fur stole.

‘You bunch of bastards,’ Tim said, casting his eyes over the six members of the heavy rescue squad who were now held fast by his officers. ‘If it’s not enough that people have their homes blown to bits by the Luftwaffe every night, they have to come home to find that scum like you have rifled through their belongings and helped yourselves. Cuff ’em, boys.’

There was a rattle of chains as the officers snapped their handcuffs on the prisoners. As Tim reached in to retrieve his handcuffs from his trench-coat pocket, the heavy rescue team leader bunched up his shoulders and curled his hands into hammer-like fists.

Tim grinned. ‘Please, Chalky, make me happy and resist arrest.’

‘Right,’ said Tim, shoving Chalky through the battleship-grey metal door into number four cell to join the rest of his crew. ‘I hope you get a bit of sleep so you’re all bright-eyed and bushy-tailed when you step into the Thames Magistrate’s Court’s dock tomorrow morning. Although I wouldn’t worry too much if you don’t,’ he continued, ‘because you won’t be there very long. Thanks to the Emergency Powers Act, looting is now a capital offence. The presiding beak will be sending you to the Crown Court so fast your boots won’t touch the ground.’

‘Piss off,’ snarled Chalky.

Giving him the friendliest of smiles, Tim slammed the door shut and turned the key. Handing it to the night-duty officer assigned to guard the cells, he trotted up the couple of concrete steps and along the central corridor back into the police station’s front office.

As with all police stations, this space was the hub of activity. But now, at almost ten o’clock, and with the night duty already out on their beats, there were only a couple of officers sitting at their desks finishing off reports before clocking off, although the smell of male sweat and fags lingered.

Charlie Webb, who was a few years short of hanging up his helmet and truncheon for good, was a lean, balding individual whose square shoulders made it look as if he’d left the coat hanger in his uniform jacket. He was standing at a chest-height desk with a leather-bound record book on it as he completed the final details of the arrests.

Taking a long drag on his half-smoked cigarette, he looked up as Tim entered.

‘You’re a bit lost, aren’t you, Wallace?’ Giving Tim a jaundice look, Webb nodded towards the main door. ‘Wapping nick is that way.’

‘Me and the boys have been following White and his crew for a couple of weeks and it just so happens that we caught them on your patch,’ Tim replied.

‘Officers, even bloody CID ones, stuck to their own areas when I was on the beat,’ Webb sighed, flicking ash into the already overloaded Bakelite ashtray on the desk.

‘Well, there is a war on,’ said Tim.

‘So they tell me. Is that the last of ’em?’

‘That it is,’ he replied.

‘Good riddance to them, I say,’ Webb replied. ‘If I’d caught them, they wouldn’t be looking so pretty.’

‘I catch wrong’uns; I don’t act like them,’ Tim said, his mouth lifting in a sideways smile. ‘Although I did offer White the chance to resist arrest. Have the rest of the team been signed off?’

Webb nodded. ‘About twenty minutes ago. Your DS said he’d be in first thing to get the witness statements ready for court.’ The station sergeant’s thin lips lifted in a sardonic smile. ‘I see you’ve got ’im properly trained.’

Tim smiled and crossing to the coat stand in the corner he took down his trench coat. He shrugged it on over his charcoal-grey suit then, running his fingers through his dark-brown hair, he unhooked his fedora.

‘Be seeing you, Sarge,’ he said, tugging the brim slightly down over his left eye as he headed for the back door of the station.

‘Not if I see you first,’ Webb called after him. ‘And find villains to nick on your own patch in future.’

Tim laughed and raised his hand in acknowledgement.

Passing half a dozen empty offices along the rear corridor, Tim pushed open the green door at the end and stepped out into the backyard. The tangy smell of manure and hay from the Mounted Branch horses in the stables opposite drifted into his nostrils as he headed for the double gates.

The temperature had dropped several degrees in the hour and a half he’d been in the station, and the thick cloud that had blanketed the area had disappeared, leaving a clear moonlit sky. Bad news: even now, dozens of Luftwaffe pilots were probably taxiing their Messerschmitts and Dorniers along the captured runways in northern France.

Resigned to another night on a truckle bed in the section house’s bomb shelter basement rather than his comfortable room upstairs, Tim had only walked a couple of steps when a Black Maria parked across the road tooted.

‘Where you heading, Inspector?’ asked the officer, leaning out of the passenger window.

‘Tenter Street,’ Tim replied.

‘I can give you a lift to Stepney station,’ came the reply.

‘You’re a pal,’ said Tim.

‘Hop in.’

Going to the back of the vehicle, Tim opened one of the van’s rear doors and climbed in. Sitting himself on one of the side benches, he planted his boots wide to steady himself and the van pulled away from the kerb.

As they trundled westwards, past St Clements Hospital and People’s Palace, Tim and his fellow officers exchanged a couple of amusing stories and complained about the lack of equipment. Within ten minutes, they were pulling up just before Stepney Green underground station in Mile End Road.

Clambering to the rear of the van, Tim unlocked the back door and jumped down. ‘Thanks, mates.’

‘Any time,’ the driver called over his shoulder.

Slamming the van door, he banged on the side and it sped away, turning left into Globe Road.

H Division’s section house was situated in Tenter Street, behind Leman Street police station, just a stone’s throw from the Tower of London and a couple of miles’ walk along Mile End Road; however, after waiting for an ARP lorry to roll past, Tim crossed the road to take a shortcut.

Switching on his torch, he walked south down Whitehorse Lane, past St Winifred’s sprawling rectory and into Stepney High Street, just as the clock on the ancient church of the same name struck ten thirty. But as he strode past the graveyard, he noticed the lone figure of a woman swaying back and forth as she sat on one of the headstones.

Tim frowned. Apart from the obvious dangers of having bombs dropped on you from a great height every night, young women, particularly if they were slightly the worse for wear, were now in peril of becoming victims of two crimes that had almost trebled since the start of the blackout eighteen months ago: sexual assault and rape. Hoping the young woman in the graveyard wasn’t such a victim, Tim stepped over the low wall surrounding the burial ground and made his way over to where she was sitting.

‘Excuse me, miss,’ he said, noting she had a suitcase on the floor next to her and a bottle of half-drunk gin in her hand. ‘Can I be of any assistance?’

She glanced up at him.

‘No thank you,’ she replied, the hint of a rural accent in her voice.

‘Then why are you sitting in a churchyard?’ he asked.

She took a swig from the bottle. ‘I’m having a rest.’

‘What, perched on a tomb in the middle of the night?’

‘Well, firstly …’ She bent her arm and looked at her wristwatch. ‘It’s … well, the light’s not very good so I don’t know the time exactly, but I think it would be safe to say it is not the middle of the night. And secondly,’ she looked up at him, ‘who are you anyway?’

‘Detective Inspector Wallace,’ Tim replied, taking his warrant card from his pocket and shining his torch on it.

She raised her eyebrows as she peered at it and seemed to unbalance for a moment, swaying dangerously to the right.

‘So you are,’ she said. ‘An instrument of the capitalist state to repress the proletariat.’

‘If you like,’ said Tim. ‘But right now I’m just a bloke who’s trying to help you stay safe.’

‘Well, Mr Policeman,’ she slurred, ‘although I’m not an expert in such matters, as far as I can remember there is no law against sitting in a graveyard at any time of the day.’

Tim took a steady breath. ‘No, there isn’t. But it’s dangerous.’

‘I can take care of myself,’ she snapped back.

Tim’s gaze ran over her willowy frame, and he gave a hard laugh. ‘Against a drunken fifteen-stone docker? I doubt it. What’s your name, miss?’

‘Mith F–f … Fl ... sss … ty Car – car … M … Miss Flissssy. ’

Tim sighed. ‘Look, miss, you’ve clearly had one too many and my concern is that sitting in a dark, isolated churchyard all alone could bring you to harm, and I wouldn’t want you to be hurt.’

Her head snapped around and Tim found himself staring into a pair of very large, very brown and very angry eyes.

Gripping the bottle, she sprang to her feet and glared at him.

‘You men are all the same,’ she said, swaying slightly. ‘You pretend you care about us and then jump into bed with the first blonde trollop …’

Tim gazed at her in the hazy torch beam for a moment then her face crumpled.

‘How could he?’ she sobbed, tears pouring down her face. ‘And with—’

The wail of an air raid siren fixed on the memorial hall roof swallowed her words.

Tim studied her as she sobbed helplessly in front of him for a moment, then he pulled his folded handkerchief from his jacket pocket and offered it to her. ‘It’s clean.’

‘Tha … tha … thank y–you,’ she shivered.

Tearing open the buttons of his overcoat, he shrugged it off.

‘There, there, miss,’ he said, wrapping it around her shaking shoulders, catching a faint hint of perfume as he did. ‘Whoever he is he’s not worth it.’

‘No, he’s not,’ she squeaked. ‘The pig.’

She raised her head and gave him a little tipsy smile. ‘Your coat is warm.’

Running his gaze over her high-cheek-boned, oval face and slightly unfocused brown eyes, Tim realised he still had his arm around her.

He also realised that her eyes were level with his chin so he only needed to dip his head slightly to press his lips onto hers.

Feeling a bit of a pig himself, Tim let her go.

‘Now, miss,’ he said, pulling down the front of his jacket then picking up her suitcase, ‘the bombers will be here in a short while, so let’s get you to safety. Come with me. And I’ll take that,’ he added, extracting the bottle of Gordon’s from her hand.

Taking her elbow, Tim guided her towards the front door of the church. Swamped in his coat, the young woman took a couple of steps then wobbled off her heels. His arm went around her again to steady her.

With her leaning heavily on him for support, they made their way to the entrance of St Winifred’s church and joined the stragglers going into its shelter in the crypt.

Although in the middle of one of the most deprived and dilapidated areas of London, the interior of St Winifred’s was very much as you’d find in any village church. A wide central aisle flanked by solid rows of pews led to the chancel, which had a Lady chapel on one side and the vestry and an enormous multi-piped organ on the other. There were memorials to the parish’s past rich and famous along with military plaques and ragged and threadbare regimental flags hanging above.

To be honest, after seeing his mother praying daily for deliverance from the hell of her marriage, Tim was pretty much done with the Almighty, but even he could appreciate the beauty and tranquility of Stepney’s ancient parish church.

‘Your missis not well or something, mate?’ asked the elderly ARP warden who was ushering people in.

‘She’s not my wife,’ Tim replied.

The woman slumped against him raised her head. ‘I c-certainly am not,’ she slurred. ‘Cause marriage sss a institu … instiuu tun impo–oo on workers assss.’

Her head slumped against his shoulder again.

‘I’m a copper at Wapping nick,’ Tim explained, adjusting his hold on her. ‘I’ve just found this young lady sitting on one of the gravestones, so I thought you might know her?’

‘She looks familiar.’ The warden frowned. ‘I ’ope as how she ain’t one of those Cable Street floozies looking for trade up this way.’

Tim glanced at the drunken young woman’s expensive polished shoes.

‘She’s not. But she’s certainly had a skinful.’ He held up the bottle of gin. ‘I think she’s been unlucky in love.’

‘Haven’t we all?’ chuckled the warden. ‘Take her down to the crypt and I’m sure one of the WVS girls will find her a bunk where she can sleep it off.’

Gripping the woman’s shoulders again, Tim guided her past the first-aider preparing for the night ahead in the Lady chapel and headed towards the arched door in front of the chancel. After waiting for a mother with her baby to descend, Tim ducked his head and – scraping the crown of his hat against the stonework as he entered and holding her suitcase and gin bottle in the other hand – guided the young woman down the worn narrow steps.

The crypt was roughly the same size as the ancient building above and lit by a string of lights along the ceiling. Now, as it was almost eleven, the lights were being turned off and many of those sheltering were tucked up in the bunk beds at the far end of the cellar. In one of the alcoves, a couple of matrons in bottle-green WVS uniforms were tidying away. Not everyone had turned in for the night, though: a small cluster of women were sitting on deckchairs by a hurricane light, knitting. They looked around as Tim and his drunken companion lumbered in. Horror flashed across one of the knitter’s faces and thrusting aside her needles, she jumped up and dashed towards them.

‘Fliss!’

The woman slumped against Tim slowly raised her head. ‘Oh, Prue.’

Slipping out of Tim’s supportive arm, and letting his coat slip to the floor, she staggered forward and wrapped her arms about the auburn-haired young woman.

‘I take it you know her,’ said Tim, putting the suitcase on the floor.

‘Yes, she’s my sister,’ the knitter replied. ‘Where did you find her?’

‘Sitting on one of the gravestones outside. With this …’ He handed her the gin bottle.

‘You were right, Prue,’ said Fliss, looking blearily at her sister. ‘Giles sss … a pig and I h-hate him.’

She slumped against Prue, who staggered under her sister’s weight. Tim stepped forward and took up the strain.

‘I’m DI Wallace from Wapping nick,’ he said, feeling it necessary to introduce himself to the young woman whose sister was currently draped over him. ‘Is there somewhere we could lie her down?’ he asked, as Fliss transferred her arms from her sister’s neck to his, pressing her soft breasts rather pleasingly into his chest.

Prue nodded. ‘Over here.’

They started off but after a couple of steps Fliss’s legs gave way. Catching her as she fell, Tim held her in his arms and her head flopped into his shoulder. With a couple of strands of her hair caught on his evening bristles, Tim stepped over his coat on the floor and followed her sister to the rear of the shelter. Gently laying the young women on one of the bottom bunks, he turned her on her side, so her head was hanging over the edge.

Tim straightened up and took his pocketbook from his inside pocket. ‘She was unable to give her name—’

‘I’m not surprised,’ cut in Prue, glancing down at her unconscious sister.

‘So would you oblige?’ He dabbed the end of his pencil on his tongue. ‘Is she miss or mrs?’

‘Miss,’ she replied. ‘Carmichael. Felicity Hermione Evadne. Seven St George’s Drive, Pimlico.’

‘Date of birth?’ Tim asked as he scribbled down the address.

‘Thirtieth June, nineteen-fifteen.’

Tim looked up. ‘And you are?’

‘Mrs Quinn. Prudence.’ She raised an eyebrow. ‘I hope you’re not going to ask me my date of birth, Inspector.’

Tim grinned. ‘I wouldn’t be that cheeky.’ He returned his pocketbook to its place. ‘Now I know your sister is in safe hands I’ll be on my way.’

He scooped his crumpled trench coat off the floor.

‘There might still be a cup in the pot,’ Prue said, nodding towards the two WVS women at the refreshments table.

‘That’s very kind,’ Tim replied, as he shrugged it on, ‘but I’ve been on duty since six this morning, so all I’m in need of now is my bed.’ He touched the front of his fedora. ‘Goodnight, Mrs Quinn.’

‘Goodnight, Officer,’ she replied. ‘And thank you for looking after her.’

‘Don’t mention it; just doing my duty as an “instrument of the capitalist state”,’ said Tim, raising an eyebrow and the corresponding corner of his mouth.

Prue pulled a face. ‘I’m afraid my sister is rather outspoken.’

‘So I discovered.’ He glanced at the young woman, her auburn hair in disarray snoring softly. ‘She’s going to know about it in the morning.’

Prue raised her eyebrow again. ‘That’s putting it mildly.’ She looked fondly at her sister and sighed. ‘I suppose that’s what love can drive you to.’

Tim touched the brim of his hat again. ‘Which is why I studiously avoid it.’

Chapter three

‘MORNING, HARRY,’ said Kenny Williams, the Colonial & Orient shipping company’s clerk, as he stopped in front of the dock worker.

‘Morning,’ Harry Gunn replied, then took a long drag on his roll-up.

It was Wednesday, and as he had been every working day for half his thirty years, Harry was standing in London Dock. The Maid of Gibraltar, a 5,500-ton steam merchant cargo ship, was anchored beside him in Shadwell New Basin.

It was so early in the morning the first streaks of winter sunlight had yet to make their appearance in the eastern sky. In fact, it was so early that the blackout was still in force and would be for another two hours until eight o’clock.

It was freezing, too, which was to be expected just five weeks after the New Year. There were even clumps of soot-dusted snow from last week’s downfall sitting on the dockside office roofs. And the grey water of the Thames, thirty feet below where they were standing, was as cold and forbidding as the jaws of Hades. Despite this, Harry was dressed in his usual worn cord trousers, collarless shirt and shapeless donkey jacket – and that would soon be off once he started humping hundredweight sacks about in the hold.

‘The Luftwaffe made a bit of a mess of the place last night, don’t you think?’ continued the company’s eagle-eyed tally man, gesturing towards the dozen firemen who were still hosing down a warehouse. ‘It’s Logan and McKay’s, isn’t it?’

Running his gaze over the gutted building on the other side of the quay, Harry nodded.

Kenny frowned. ‘What you waiting around for?’

Spotting Ernie Milligan, the Fairchild & Son Stevedore Company’s representative, marching across the unloading area, Harry grinned. ‘Him.’

Kenny glanced behind him. ‘I’ll leave you to it then, Harry.’

He left to take up his position on deck by the open hatch ready to count and make a note of what was unloaded for the import company.

‘Milligan looks a mite put out, don’t he?’ said Ben, who had just strolled over to join them.

Ben was not only the number-one man in Harry’s team but also his younger brother. He had the same red hue in his hair and tendency to grow freckles in the sun. He hadn’t yet reached Harry’s five foot ten, but after two years on the docks he was certainly building muscle.

In fact, all of the eight-strong gang of men loitering around Harry were Gunn family members, either by birth or by marriage.

Harry sniggered at the red-faced hiring clerk slipping and sliding across the concrete waterfront.

‘What do you think you’re playing at, Gunn?’ Ernie shouted, waving his short arms as he approached. ‘The crane operator and the tally man are ready, so why are you and your team standing around like a bunch of bloody lemons?’

Peeling himself off the cast-iron bollard he’d been leaning on for the past twenty minutes, Harry pulled himself up to his full height. ‘The sacks are wonky. Aren’t they, boys?’

The men close by muttered their agreement.

Ernie frowned. ‘Wonky? What d’you mean “wonky”?’

‘I mean it’s going to take a bit more jiggery-pokery to get ’em out of the hold than a quid a ton,’ Harry replied.

In the muted light shining up from the Maid of Gibraltar’s number-three hold, Ernie’s fleshy jowls started to quiver. ‘But that’s what we agreed.’

‘We did,’ Harry agreed. ‘But before I realised that the price set by capitalist scum exploited the working man.’

Ernie ran his fingers through his thinning hair. ‘But that flour needs unloading before the rats get in. If it spoils, I’ll have some Ministry of Food fellas down here asking why.’

Harry held the hiring governor’s furious glare. ‘A guinea a ton.’

‘That’s blackmail!’

‘A guinea a ton,’ repeated Harry. ‘Or, as shop steward of the Transport and General Workers’ Union, I’ll convene a members’ meeting.’

‘You can’t,’ snapped Ernie. ‘Strikes are illegal.’

‘I ain’t calling a strike, Milligan,’ Harry replied. ‘But as the dockworkers’ shop steward, I will convene a union meeting as I’m entitled to do and I’ll be sending word to our members in London and St Katherine Docks, too. Of course, they’ll have to down tools but—’

‘All right, all right, a guinea a ton it is,’ cut in Ernie. ‘But I want it all out by knocking-off time so the shore team can get in and clean.’

Harry took another lungful of nicotine down then, pinching it out, he stowed the roll-up behind his right ear.

‘Right, lads,’ he said, rubbing his hands together, ‘you ’eard what Ernie said, so lets get on wiv it.’

The men sprang into action and clambered on board the ship.

‘You pull a stunt like this again, Gunn,’ snarled Ernie, ‘and I’ll—’

‘You’ll what?’ cut in Harry. ‘Ignore us standing outside the gates at morning call?’ He bared his teeth and loomed over the diminutive clerk. ‘I wouldn’t do that if you know what’s good for you.’

Ernie, fleshy jowls quivering, glared up at him for a moment then turned and marched back across the unloading area.

‘I ’ope as ’ow you ain’t gone and upset little Ernie,’ said Micky, Ernie’s ginger-haired, freckle-faced cousin, as he strolled past with a tarpaulin cargo sling draped over his shoulder.

Harry looked around.

‘Don’t I always?’ he said, grinning. ‘And, Micky, do me a favour. When you trot off to the bog, have a quick squint in the L&M.’ He nodded towards the smouldering warehouse on the other side of the water. ‘I saw Dicky Robbins’ crew moving tea chests in there on Tuesday and our national brew being in short supply, it’ll be worth our while to rescue a crate or two.’

Chapter four

DESPERATELY TRYING not to move her head off the upright, Fliss raised the mug of black coffee to her lips and took a sip.

Holding the hot, sweet liquid in her mouth until the yawning feeling in her stomach subsided, she swallowed it down.

‘How are you feeling, Fliss?’

Slowly lifting her head, she looked up at her sister Prue, who was straightening the bed linen on the top bunk.

Fliss gave her a wan smile. ‘Not so bad.’

That, of course, was a complete lie because truthfully she didn’t believe anyone could feel this ghastly and still be this side of the grave.

‘What’s the time?’ she asked.

‘Just before seven,’ her sister replied. ‘The all-clear sounded an hour ago.’

‘Did it?’

Prue gave her an exasperate look. ‘Can’t you remember anything?’

‘I remember walking in on that louse Giles.’ With the raw pain in her chest tightening, Fliss told her sister about discovering Giles in bed with the receptionist from the Workers’ Clarion.

Prue frowned. ‘The toerag. Then what happened?’

‘We argued.’

‘Argued!’ her sister shrieked. ‘I would have broken a vase or something over his head.’

Fliss gave her a sideways look.

Prue laughed. ‘You didn’t hit him, did you?’

‘I punched him in the mouth,’ Fliss replied, remembering the satisfaction as her fist busted Giles’s bottom lip. ‘After which, I packed my suitcase and left. I wandered up to Victoria station and caught a train home.’

‘So, when did you acquire this?’ Prue held up the bottle of Gordon’s gin.

Staring at the green glass flickering in the low lighting of the overhead bulbs, fragmented images of the previous day passed across Fliss’s pounding brain. ‘In the pub opposite Stepney station, I think. I needed a bit of Dutch courage before I pitched up at the rectory.’

Prue gave her a deeply sympathetic look, as well she might.

‘So you don’t remember how you got here?’

Fliss swallowed another mouthful of coffee. ‘No, it’s a complete blank.’

‘Well, according to the police officer who found you, you were sitting on one of the gravestones in the churchyard,’ Prue explained. ‘Unsurprisingly, as you were completely sozzled, you couldn’t tell him your name but luckily, as you were obviously incapable of looking after yourself and the air raid siren had just gone off, he brought you here. And when I say brought you, Fliss, I mean carried you, because you were, as they say around these parts, legless. What are you going to do now?’

‘Go and tell Mother that I’ve come home to do a piece on something for the paper,’ said Fliss.

‘About what?’

‘I don’t know; the docks or something,’ said Fliss, as the lamps went on overhead and light sliced through her eyes. ‘I just need a week or two to figure out what to do next.’

‘Why don’t you just tell her the truth?’

An image of her mother’s tight-lipped face loomed into Fliss’s mind. She shook her head then bitterly wished she hadn’t.

‘I can’t,’ she replied. ‘I just can’t face her. Not like—’

A wave of nausea rose up. Grabbing the bucket alongside her bunk, Fliss threw herself on her knees and retched up what was left in her hollow stomach.

With a ragged tooth saw grinding slowly through her brain, Fliss leaned on the side of pail.

‘I’d come with you,’ said Prue as she rubbed her back gently, ‘but …’

Raising her head, Fliss forced a smile. ‘It’s all right, Sis. Anyhow, I’d better make myself look respectable before I pitch up at the rectory.’

Prue nodded. ‘There’s a couple of washing cubicles in the side crypt behind the stairs. I’ll get your washbag.’

As her sister opened her case, which had been stowed under the bed, and rummaged around in the contents, Fliss summoned all her strength and stood up.

‘You know,’ said Prue as she handed Fliss her washbag, ‘it’s a pity you can’t remember your knight in shining armour, because,’ an oddly starry-eyed expression spread across her pretty face, ‘he really was quite a dish. Had a bit of the Errol Flynn about him but without the moustache.’

Fliss gave a dry, mirthless laugh. ‘Well, it wouldn’t matter to me if he was actually Errol Flynn in a doublet and hose because, Prue, from now on I’m off men completely.’

With the blood thundering in her ears, Fliss waited for the rag and bone man’s horse and wagon to trundle past then adjusted her grip on her suitcase and crossed Whitehorse Lane.

Stopping in front of two Portland-stone pillars that had once had an ornate wrought-iron trellis gate between them that was now most likely part of a spitfire or battleship, Fliss studied her parents’ home, St Winifred’s Rectory.

Although the vast majority of houses in this part of London were squat, two-up two-down terraced houses or tightly packed tenements, the manse where her father, the Reverend Hugh Carmichael, and her mother, Marjorie, had moved to almost ten months ago was more like a dwelling for the lord of the manor rather than a parish priest.

Of course, the homes provided to the clergy by the established Church of the land, though often draughty and short of modern amenities such as hot running water and a stove built in the current century, could never have been described as poky. But with the baronial-style casement windows protected now with criss-crossed tape, five bedrooms, three reception rooms, a study, a music room, kitchen and cellar, St Winifred’s Rectory rivalled most bishops’ palaces. There were even a couple of mature apple trees thrusting their bare winter branches above the side wall.

Of course, in times past, along with the clergy’s family, this would have been the workplace for a bevy of servants who would have been housed in quarters behind the row of dormer windows under the rafters.

Fliss studied the solid front door for a moment, then with the bustling exhaust-choked street behind her, she entered the rectory’s enclosed garden and walked up the path.