8,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Lightning Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

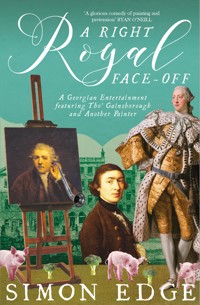

It is 1777, and England's second-greatest portrait artist, Thomas Gainsborough, has a thriving practice a stone's throw from London's royal palaces. Meanwhile, the press talks up his rivalry with Sir Joshua Reynolds, the pedantic theoretician who is the top dog of British portraiture. Gainsborough loathes pandering to grand sitters, but he changes his tune when he is commissioned to paint King George III and his large family. In their final, most bitter competition, who will be chosen as court painter, Tom or Sir Joshua? Two and a half centuries later, a badly damaged painting turns up on a downmarket TV antiques show being filmed in Suffolk. Could the monstrosity really be, as its eccentric owner claims, a Gainsborough? If so, who is the sitter? And why does he have donkey's ears? Mixing ancient and modern as he did in his acclaimed debut The Hopkins Conundrum, Simon Edge takes aim at fakery and pretension in this highly original celebration of one of our greatest artists. 'A glorious comedy of painting and pretension' Ryan O'Neill

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

Published in 2019

by Lightning Books Ltd

Imprint of EyeStorm Media

312 Uxbridge Road

Rickmansworth

Hertfordshire

WD3 8YL

www.lightning-books.com

Copyright © Simon Edge 2019

Cover by Ifan Bates

The moral right of the author has been asserted. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Printed by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY

ISBN: 978-1-78563-131-3

In memory of Nick Decalmer

Contents

1

Pall-mall, London, Feb. 2nd, 1777

3

4

Pall-mall,April 22nd, 1777

6

7

Pall-mall, June 3rd, 1779

9

10

Pall-mall, Feb. 21st, 1780

12

13

Pall-mall, Oct. 17th, 1781

15

16

Pall-mall, Nov. 15th, 1782

18

19

Pall-mall, April 11th, 1784

21

22

Pall-mall, Nov. 12th, 1784

24

Pall-mall, February 10th, 1785

Afterword

About the Author

Other books

1

The Duchess, it was easy to see, enjoyed being looked at. This was just as well. As the most scandalous woman in England, it was her fate to be the centre of attention wherever she went, whether she liked it or not.

At thirty-four, she was long past her prime. Even in the flickering candlelight, more lines were visible around her eyes than had been there when she last sat – more precisely, stood – for Tom, and she wore a thicker layer of paint on her face. Nevertheless, her allure remained immense. Her eyes, behind those legendarily long lashes, spoke of love to any beholder lucky enough to have them rest upon him. Her mouth seemed permanently organised into a pout of such coquettish power that strong men were enfeebled. Today she wore a gown of sensuous crimson silk, in the same shade as the ermine-trimmed robe strewn ornamentally over the tall plinth next to her, alongside her coronet. Her petticoats exploded out of the front of her gown in a dazzle of silver brocade. Her hair, powdered a fashionable iron grey, towered majestically towards the ceiling, and her gleaming white arms and breasts nestled in teasing lace flounces. She was ravishing still, and she knew it, which was undoubtedly why she was content to stand nearly an hour in the same pose, her rouged cheek resting on one slender finger, her eyes fixed somewhere over Tom’s right shoulder, as he worked barely a foot away.

The Duke, her husband, had also arrived in full royal fig, the gold chain around his neck clanking against the gold buttons of his waistcoat. Two or three years younger than his wife, he had put behind him his days as the worst rake in town, and his regard for her was absolute. That they had arrived in tandem was a mark of this devotion.

Unlike his wife, the Duke was a fidget, unable to stay still for more than a few moments at a time. In the past hour, he had paced around the studio, causing havoc in his wake as his sweeping velvet train knocked over boxes, jars and a pile of empty frames. Eventually, the Duchess had successfully enjoined him to remove his cloak, and since the couple had not brought their own footman, she had taken it upon herself to lay it neatly on a side-table. But still the Duke had tripped over an easel as he persisted in trying to peer at the faces looking back at him from their shadowy frames on the walls. Every time he knocked into something, he cursed loudly at the darkness that Tom insisted on maintaining in the studio, even though it was bright noon outside.

‘Can’t you open the blasted curtains, man?’ he demanded. ‘A feller can’t see a perishing thing in here.’

Tom stood firm. Years of experience had taught him that it was easier to capture a precise likeness when only the face was lit, and all its surroundings were in the deepest possible gloom. If that meant a member of the Royal Family tripping over everything because he could not remain at repose for more than a few seconds, so be it.

The Duke of Cumberland was the younger and more disgraceful of the King’s two surviving brothers, although both were too much for His Majesty. The middle brother, the Duke of Gloucester, had already visited the studio, as Cumberland now discovered with a shout of surprise.

‘Damn me, if it isn’t Brother Billy! It’s so damned dark, I didn’t notice him before.’

The full-length canvas was leaning against the wall just behind where Tom stood, which meant that this cry was delivered very close to his left ear. He hoped the Duchess did not notice his own involuntary wince at the outburst. She was still looking over his right shoulder, but her pouting lips twitched in amusement.

‘How is it, my dear? Is it very like?’

‘Hard to see in this damned gloom.’

Tom could sense the Duke peering closer towards the portrait.

‘What the devil are these trees? A child could do better!’

Tom coughed discreetly.

‘The picture is unfinished, sir. It is customary to finish the setting last.’

‘What of the face, my dear? Is it like?’

‘Behhhh…passing like,’ the Duke conceded.

Tom sensed that his visitor did not bestow compliments lightly.

‘Damned tricky for you, though,’ he continued, prodding Tom on the shoulder with his cane.

The jolt made Tom’s hand jump, so that a dab of crimson from the Duchess’s right cheekbone now spilled onto what ought to be the distant background.

‘How is that, sir?’ he asked, mopping away the rogue colour with a damp piece of sponge from a saucer beside him, and hoping the irritation did not sound in his voice.

‘Let’s face it, he’s an ugly blighter, and ye’d be mad not to try and pretty him up a little, wouldn’t ye? Eh? Ha!’

Tom cleared his throat. ‘His Royal Highness is a man of distinguished aspect, sir. One would expect nothing less from a member of such an illustrious family.’

The Duke sniffed.

‘Devil take me if I’m that ugly. Always thought he had the look of a sheep, old Billy. It’s the way his nose starts too high up his face. Ye’ve caught that, indeed ye have.’

The truth was, he was right, and Tom had thought much the same when he was working on the painting. Not that he could possibly say so. If blood was thicker than water, royal blood was thicker still.

The Duchess came to his rescue.

‘I believe there is also a portrait of Maria, my dear. I think I saw it as we entered the room.’

‘Where?’

‘Next to your brother. Just to the right.’

‘O yes, bless me, there she is, the old girl. Yes, ye’ve certainly caught her. Not a looker, bless me, but what can ye expect when her husband has the face of a tup?’

There now came a series of adenoidal snorts from immediately behind Tom. The Duke was laughing.

Without moving her head, the Duchess turned her eyes on her painter.

‘Did they also sit for you together?’

‘No, ma’am. The picture of Her Royal Highness, the Duchess, was painted previously, when she was still Lady Waldegrave. At least, when we thought…’

He stopped, for fear of saying the wrong thing.

It was the Duke’s turn to help him out.

‘Before the world knew that my brother had married the old stick in secret?’

He snorted again, even as the Duchess tutted a gentle rebuke.

‘And you painted His Royal Highness on a later occasion?’ she asked.

‘Yes,’ said Tom. ‘They both visited me here, but it was only the Duke of Gloucester who sat.’

‘I don’t believe I’ve seen either picture before. Did you not show them at the Academy?’

‘As I say, ma’am, the portrait of the Duke is not finished. I did endeavour to show Lady Waldegrave – that’s to say, Her Royal Highness, the Duchess – the very year I painted her, ma’am. I regret to say that I was…obstructed.’

‘Obstructed?’ boomed the Duke. ‘Who the devil by?’

Tom used a cloth to daub some black shadow along the outline of the Duchess’ nose.

‘I submitted the picture to the Academy, sir, but the council, in its wisdom, declined to exhibit it. The picture was returned and it has remained here ever since.’

‘Damned cheek! Why the blazes did they do that?’

Again, this was sensitive.

‘I believe the president of the council feared that the picture of Her Royal Highness, as we had recently learned her to be, might cause embarrassment to His Majesty when he visited the exhibition.’

Which might have caused embarrassment in turn – he thought, but did not say aloud – to the president himself.

‘Ha!’ said the Duke. ‘Ridiculous business, the whole perishing thing. If the King would only mind his own damned business about who married who in his own damned family, nobody would need to be embarrassed at all.’

Tom suddenly found it necessary to focus very minutely on the set of the Duchess’ left eyebrow, using his finest brush and leaning right into the canvas.

‘My love, you mustn’t speak of your brother so,’ she said, her amused pout as intact as ever. ‘You’re making poor Mr Gainsborough uncomfortable. In any case, it was not the King who refused to show dear Maria’s portrait, but the president of the Academy.’

‘Damned fool thing to do. Who is the president? Do we know him?’

‘We sat for him, my dear. Do you remember, we went to his house in Leicester Fields.’

‘The feller with the blasted ear trumpet?’

‘Indeed, my dear. Sir Joshua.’

‘Ridiculous feller. Don’t know why he needed the trumpet. I had nothing to say to him. Just get on with it and paint, man: that’s my view.’

Tom wished the same rule might apply in his own studio.

He turned his attention to the Duchess’ mouth. Those lips would have to be made to pout a little less, for her sake and his own. Picking up the mauve chalk that he used for all his initial sketching on the canvas, he traced the outline a little wider, and at once she was more serious; languid, even. The likeness was of course what mattered but, when a subject had such a surfeit of vivacity, there was no harm in holding a little of it back in the studio, and keeping it from the world at large.

He gulped in distaste as a blast of noxious breath passed over his left shoulder. The Duke was standing even closer behind him now, inspecting his work. Tom’s instinct was to reach for a perfume-soaked kerchief and press it to his nose, as he might when he walked passed a reeking mess of soil in the street. In this case, it would hardly be wise. He did his best to breathe only through his mouth, trying discreetly to move his head away from the Duke’s line of breathing.

‘Why’s her bally head so close to the edge? Seems an irregular sort of composition to me. Is this the modern way? Damned idiotic, if it is.’

‘That, sir, is just while I’m working. As you can see, the canvas is still loose. That enables me to move it around the easel to bring it as close as possible to the element of the subject I am painting – in this case, Her Royal Highness’ head. In that way, I find can get the likeness much better.’

‘Hmmm,’ the Duke considered. ‘There’s not much there yet, but it’s not bad. He’s beginning to catch you, my angel.’

‘Of course he is. He is famous for the quality of his likeness.’

Tom inclined his head, accepting the compliment. It was true. Nobody else could come near him in that respect. Certainly not Sir Joshua.

‘At least he isn’t making us dress in damned silly costumes like that other feller wanted. I remember now. I refused. Told him it was beneath a man’s dignity. Why the devil does he do that?’

Tom shrugged.

‘I believe he learned it in Italy. He calls it the Grand Style. He likes to elevate his sitters, make them into characters from ancient history and legend, even if they are elevated enough already, as Your Royal Highnesses so obviously are. If he makes a big fuss over the clothes and the setting, he hopes that nobody will notice that the faces are nothing like.’

The Duchess laughed, a clear peal of merriment. As she tilted her head back to do so, Tom caught a glimpse of the soft, white skin under her chin.

‘Is it true that you and Sir Joshua are great enemies?’ she asked, returning to her proper pose.

Tom stood back from his work, hoping it would encourage the Duke at his left flank to back off too.

‘Not at all, ma’am. It’s true that I was in a fury with him when he refused my picture. As Your Royal Highness may know, I have refused to send work to the Academy in the years since then. Rather than subject my pictures to Sir Joshua’s petty-fogging prejudices, I have mounted an annual exhibition here at my home instead. But I am still a member of the Academy, and I have been away too long. I have decided it is time to show my face – and, therefore, your faces – there this year.’

‘Of course you must. You have sulked quite long enough.’

Tom smiled.

‘Do you hear, my dear? Mr Gainsborough plans to send our pictures to the Academy this year. We will see if my face is too shocking to put before the King, as dear Maria’s was.’

‘If he won’t see you in person, he can damned well see a picture of you, to remind him you exist. Gainsborough, did you know the King won’t receive my wife?’

Tom did know. All of London did. The Duke and Duchess lived in crenellated splendour in Windsor Great Park. They had their own private palace – inherited from the previous Duke of Cumberland, the notorious Butcher of Culloden – which they filled with gamblers and libertines to make up for the snub of not being welcome at Court.

‘His Majesty is a terrible jealous feller,’ the Duke continued. ‘He puts himself about as a simple, saintly soul, but the truth of it is, he’s eaten up with envy. He decided that my brother and I should each marry a dumpy German princess from a runtish little kingdom the size of Berkshire, just like he did, and when we refused to do so, he couldn’t forgive us. If he thinks that’s where his duty lies, so be it, but why must we all suffer? I was never going to be king and I married for love, damn me. I won’t apologise to a soul for it.’

‘Nor should you, sir,’ said Tom, wondering how he might nudge the subject onto more loyal ground, when protocol demanded that he only speak when spoken to.

Once again the Duchess came to his rescue.

‘Is it true that Sir Joshua is too miserly to mix the proper colours?’

She turned to glance at him for a second, and he thanked her with his eyes.

‘Whether it is for meanness or for want of knowledge, I cannot say,’ he said. ‘But it is true that his colours are apt to disappear. Especially the reds. However much rouge you wear when you sit for him, you will have none left in six months.’

His guests both laughed – she with her musical peals, he with his animal snort.

‘He shouldn’t paint his own face then,’ boomed the Duke. ‘Red is the only damn colour he needs for that.’

Tom allowed himself to join in with that one. It was not bad, for the Duke.

The shape of the Duchess’ face and hair were in place now. She would need another sitting to get her eyes right, and the full texture of her skin, after which he would rearrange the canvas and set to work on her silk finery. For the moment, it was time for husband and wife to change places. If nothing else, it would stop the Duke breathing over his shoulder.

He rang for his footman, a spotty youth who had recently arrived in the household from Suffolk. Tom had taken him on as a favour to his sister, who was on a mission to help the lad’s family. He provided board and lodging, and half a crown a week, but it was not obvious what he gained in return, particularly with the new tax of a guinea a head to be paid on male servants. The lad tugged constantly at his collar, as if his new livery were choking him, and he had flatly refused to run errands out of doors, so convinced was he that he would be press-ganged into service in the American war. He could at least earn his keep indoors.

To his surprise, the lad appeared in an instant – almost as if he had been hanging around outside the door.

‘Fetch a chair for Her Royal Highness. And when you’ve done that, help His Royal Highness into his cloak.’

The Duke’s top layer of ermine was rearranged around his shoulders, with his golden chain over it, and Tom placed him where his wife had been, this time facing in the opposite direction, so that his face was pointing over Tom’s left shoulder.

The face itself, he now observed properly, was not displeasing. The Duke’s nose was straight, his brow was high under his white-powdered wig and his eyes were comfortably set, neither too close together, like the Duke of Gloucester, nor too wide apart, like the King, who had been handsome as a young man but in middle age, from what Tom had seen in paintings, had come to look like a bullfrog. While handsome, the Duke of Cumberland had a famously vicious character, and it was hard not to see that in his cool, grey eyes. Tom must make an effort not to let that aspect show through. In his early days, it had amused him to emphasise the curl of a lip or the stiff spine of some country panjandrum, who was too caught up in his own self-regard to notice the slight. With the Royal Family it was different, because everyone was watching and the stakes were potentially a good deal higher.

As usual, he would begin with the head, which meant slinging the loose canvas over his easel so that the place where the head was due to go was as close as possible to the Duke’s own features. These were now neatly illuminated in the candlelight.

‘Will you look directly at me, sir?’

‘Like this?’

This time the blast of foul breath hit Tom full on from the front.

‘That’s it exactly, sir,’ said Tom, turning his nose into his sleeve as if he were rubbing an itch. From behind him, he heard a soft giggle. The Duchess, at least, was enjoying herself.

The Duke himself did not seem to have noticed. He was frowning faintly, with a distant look in his eyes. He appeared to be thinking.

‘I say,’ he said after a moment. ‘Once you’ve done these pictures, you could send all of them to the Academy: the Duchess and meself, and Brother Billy and Maria. Show ’em all together, hey? That would stop the King in his tracks. Ha! I tell ye what would happen then. ’Pon my soul, he’s so jealous, he’d want ye to paint him too. Mark my words, man: before ye know it, ye’ll be the Court Painter!’

‘I fear that office is already taken, sir,’ said Tom.

‘Really? By who?’

‘His name is Ramsay, sir. He is Scotch.’

‘Never heard of the blighter. Has he done me?’

‘I don’t know that he has, sir. If you do not recall sitting for him, perhaps not. He has of course painted their majesties, but I understand it has become impossible for him to paint these days. He broke his arm falling from a ladder, and now he is quite crippled.’

‘What was he doing up a ladder? Stealing apples? Ha, ha!’

‘I understand he was showing his family how to escape onto the roof in the event of fire.’

‘He had an accident while he was showing ’em how to avoid an accident?’ That adenoidal snort sounded again. For the Duke, the best jokes involved the misfortunes of others. ‘But I don’t see why he can’t paint. What’s wrong with his other arm?’

‘If he is right-handed, my dear, he cannot be expected to paint with his left,’ said the Duchess.

‘Hmmm. ’Spose you’re right. Feller shouldn’t still be Court Painter though, if he can’t paint. Stands to reason. Sounds like a job for you, Gainsborough, hey?’

Tom merely smiled.

Pall-mall, London, Feb. 2nd, 1777

To my dearest Ma

I know you cannot make out my scratchings on the page, because you never learned how. But I trust our Richard to read this out to you. It shall be one of his duties now he is become the man of the house in my absence. He is good with his school learning and ’twill be no trouble for him.

’Tis full two weeks that I am here in this great city of London. I cannot tell you if this town is a fair place or a foul one, because I have taken your instruction to heart, and when my master asks me to leave the house on some errand, I tell him nay, I dursn’t, because I will not be press-ganged into no army, whether His Majesty wills it or not. My master vents his rage on me and tells me I am a witless numbskull and a coward, but I tell him I am too afeared and he does not force me to go, so I think he is a kind man really. In consequence, of London I have seen precious little.

I can tell you that my master – that is the brother of Mrs Dupont, although he seems so much finer than her – is a great gentleman. He is much given to carousing, but he has a worthy Christian soul too, and although he is quick to temper, he is right afeared of my mistress, as we all are.

He has such a house, you never did see the like. It is full five floors high, and while it is narrow from the front, it is of large proportion inside, because it goes back farther than you would imagine. From the street, you go into a parlour, and from there into a hallway with a great circular stair with light coming down from windows in the roof. ’Tis so different from our narrow little stairway at home.

Upstairs there is a drawing room and a dining room, and above that a large chamber for my master and mistress, and two smaller ones for my master’s daughters, Miss Molly and Miss Peggy, who are grown up and like to become old maids because they have not yet found husbands.

I sleep in the top attic which I share with Mr Perkiss, the groom. I have my own little bed, we have a wash-stand between us and there is a little oak chest to keep my clothes and my private things. There is also a cook and a parlour-maid in this house, but they sleep below stairs, next to the kitchen, and the cook says she will have my guts for sausage-skins if she catches me down there when I should not ought to be. I did not understand why she spoke to me so stern, wagging her fat finger before my eye, but she has the countenance of a woman who does not waste words in jest, and I have no inclination for any part of me to be made into sausages, so I will obey her ban most diligently.

From our little window you can see St James’s-palace, which is very close by, and Buckingham-house, where the King actually lives. I swear they are no further hence than your own little cottage from All Saints-church. I have not yet set eyes on the King or Queen, but I keep looking out for them. I can also see Westminster-abbey very close, which is the most magnificent church you ever saw, far finer than St Gregory’s or St Peter’s, which afore I came here I should never have thought possible. One day, if I ever dare venture forth from this house, I should like to go to the abbey to see it for myself.

The name of our street is Pall-mall. ’Tis such a smart place to reside that, if you throw an apple over the back-garden wall, it will land in the garden of the Princess Dowager, that was the King’s mother, only she is dead now and the house stands empty. I have heard from Mr Perkiss that there is also a temple of ill-virtue in the house next to ours, but this great city London is like that, Ma, and you must not worry, I will never venture there, I swear. I do not know if my master goes, but ’tis not my business to enquire nor to wonder neither.

Every day I rise afore dawn. My duties are to carry coals up to the rooms, clean the boots, trim the lamps, lay the table for meals, answer the front door and discharge any other task that my master or my mistress desire to be done. I do perform them all to my best ability, so as Mrs Dupont will think me worthy and she will not regret sending me to my master, her brother. I have a fancy coat of red velvet, with knee breeches and stockings, and I must wear powder in my hair. You would be so proud if you could see me. I do not have much time to call my own but my mistress sometimes allows me part of a candle, as she has done this night, so I can write my tidings in this letter to you.

I have made the time to write to you now because I have such news to tell you. Can you guess who came to this very house yesterday? I know you will not, so I will tell you: not just one Royal Highness, upon my life, but two of them: the Duke of Cumberland, that is His Majesty’s youngest brother, and his wife the Duchess, that was Mrs Horton afore. They came wearing so much gold, you would not believe it. The Duchess had an actual crown with her, although it was only a little one. Mr Perkiss says she is famed for being a great strumpet, but I do not think that can be fair, because she looked very elegant and fine to me.

If I am truthful, I had never heard the name ‘Duke of Cumberland’ afore, but Perkiss told me His Royal Highness was the talk of all London a few years back, because he had what is called a ‘criminal conversation’ with a lady called Lady Grosvenor. I do not rightly know what a criminal conversation is, but whatever they conversed about, it must have been exceeding bad, because the King himself had to pay thirteen thousand pounds to Lord Grosvenor, on account of the Duke having spent all his own money already. Can you imagine such a sum? I would need to work for my master two thousand years to earn it.

Any road, Lady Grosvenor is all forgotten now and the Duke does not chase petticoats no more, says Mr Perkiss, because he has found Mrs Horton, and she is now a Royal Highness too, even though she was once a commoner just like us. Although maybe not quite so common as us. She is such a great beauty, she can make any man do most anything she wants. Not in a bad way, I do not believe. That would make her a witch, and she is not one, I am sure on it. Her eyes are too kind.

There was great to-do in the household all the morning on account of these two great personages being expected. I was dispatched to polish the door plate and sweep the step, and Miss Molly and Miss Peggy spent hours putting on their best gowns and trying to put their hair up in the high fashion. ’Twas a wasted effort for them, because they stayed upstairs the whole time, and they only saw the top of the Duke’s wig from where they were spying over the second-floor landing.

My mistress also put on a good gown, but she was fretting more about other matters than her dress. She said she would be pleased to curtsey to the Duke, but she would not know what to do if the Duchess wished to be presented to her. It would put her in an uncomfortable position, she said, because the King does not receive the Duchess at his home, so it would be disloyal for my mistress to receive the lady at hers. She looked as if she had not slept for the worry, with bags like potato sacks under her eyes, but she might as well have slept sound, because the Duke and Duchess never asked about her at all. The only room they visited was my master’s painting room at the back of the house, and my mistress was not presented to no one.

In all this fussing, my master himself was the calmest person in the house. Mr Perkiss says this is no surprise, because he is used to the society of the highest people. He has painted all the most beautiful ladies in the realm and he could dine every night with dukes, if he chose, but he don’t chuse, for he prefers the society of actors and musick-makers so they can carouse together.

As I explained to Mr Perkiss, ’tis an amazing thing that someone from our little town, whose father, as you always told me, was always in debt, can now enjoy the society of the finest folk in all England. But Mr Perkiss says my master do not find it so fine. He told me he is always grousing how much he hates the face-painting business, because it means he must doff his cap and watch his tongue with high-born folk, the like of which he does not respect but he has to pretend as how he does, else they and their friends will not come back to sit. It is a chore for my master, Mr Perkiss says, and he would rather spend his days painting trees and meadows and streams, which is called landskip. I tell you, Ma, he has bits of rock and twig in his studio to make the likenesses. If you saw one of his finished paintings, you would never know that a great tree trunk was copied from a bit of stick no bigger than your hand.

Mr Perkiss asked me if I had noticed that my master’s humour is always worse when he has passed the day in his painting room, copying the face of some fine lady or gentleman. I had not, but when I thought on it, I saw it was true. This day sennight, just after I came here for the first time, my master was locked away all day with a titled lady. Her society was evidently not to his taste, because when she was gone, he asked me to fetch his burgundy slippers and I was too long about it, whereupon he cursed me so fierce, I feared he would send me back home to you in the instant. He even shouted at Fox, his collie-dog, who normally has the run of the house, along with a bright little spaniel called Tristram, who belongs to my mistress. My master spoils Fox with meat and fish from the table, and my mistress spoils Tristram, so that to lead a dog’s life under this roof is normally to lead a most comfortable one. However, on this day that I am speaking of, my master was so vexed that he shut poor Fox out of doors to scavenge for his supper in the street. Then the next morning, he was as cheerful as you like, as if nothing had happened. When he called me into his painting room to help him lift down a frame, I saw he had been copying a little stump of vegetable called brockolly, which is like a green colly-flower. On his canvas, it became an oak tree. It is genius the way he can do it, Ma, honest it is.

Mr Perkiss says my master is considered the second-best painter in all England, only I must not ever say those words in his presence, because he would fain be the first-best and we must all behave like he is. If it displeases him to doff his cap to high-born people, it stands to reason that doffing it to royal people should displease him the most, especially as the Duke of Cumberland has the reputation of a scoundrel and his wife that of a strumpet (even if that reputation is not deserved). So when he called me to attend him in the painting room while their Highnesses were still with him, I expected his humour to be terrible. I was so afeared, my hand was shaking as I opened the door, and I waited for him to chide me for arriving too slow. But he did nothing of the sort. He just bade me fetch a chair for the Duchess. I was still shaking a little as I fetched it, but nobody seemed to think anything of it, and the Duchess sat down very nicely. When my master enquired after her comfort, she told him the chair was soft and she was content, so she was not dissatisfied with my service. Then my master required me to help the Duke on with his gown, which I also did, and nobody cursed me or told me I was a numbskull, so I must have done it right. I even helped smooth it over his shoulders, so now you can tell everyone back home, Ma, that your own son has laid hands on royalty!

In all this visit, there were no cross words directed at me or Mr Perkiss at all, and after the Duke and Duchess had gone, my master was in such fine humour that he gave me and Mr Perkiss a bottle of beer to drink in the pantry. While we drank it down, I said to Mr Perkiss that maybe my master don’t hate face-painting as much as he used to. And Mr Perkiss, he says: it all depends, my boy, on who the face belong to. We both had a good laugh at that.

Any road, Ma, the candle is almost burnt out and my poor brother will likely have no voice left after reading such a long letter out loud to you. So I will bid you a good night and I hope that you will send some news from home by the hand of my brother Richard to your ever loving and affectionate son

David

3

Gemma looked at the queue of mainly elderly hopefuls snaking down the gentle slope of the wedge-shaped town square, and wished she were somewhere else.

She had dreamed of a television career since the age of twelve. As far as her mother was concerned, boasting to family and neighbours, she had achieved that ambition. She worked in the industry, her name was on the end credits, even if they were always shrunk down so small while the next programme was trailed that nobody could read them, and she knew the coffee preference of a number of individuals whose screen appearances placed them somewhere in the lower foothills of celebrity.

It was not, however, the career that Gemma had foreseen.

In her original vision, she was a foreign correspondent, reporting with integrity and a rare sensitivity from troubled yet exotic parts, before returning to some more sedate, studio-based position and ending her career by revealing a hitherto unnoticed flair for light entertainment and fronting a tasteful but potentially cultish panel show.

Instead, a combination of bad luck, poor planning and inferior connections had brought her, at the age of twenty-seven, to a blustery square in East Anglia in the middle of February, where she was attempting to marshal two or three dozen increasingly impatient pensioners.

The show they were making was completely new and had no name recognition. Gemma tended to explain it in terms of more familiar brands: they were adding a twist to an old format, she said, a kind of Antiques on the Road meets The X-Factor or Britain’s Got Talent. That twist was a competitive element. No, she patiently explained while setting up episodes in Lincolnshire, Cheshire and South Wales, Ant and Dec were not involved, but she was confident that the show’s own, unique presenters would one day be stars of a similar class. She believed nothing of the sort, but blatant untruths were so normal in the world of light entertainment, she barely noticed she was lying.

It was her job to book accommodation for crew and talent, liaise with the venue and ensure there was enough publicity in the area to generate a good turnout from locals – because without the public, they would have no programme. In each location so far, a good crowd had turned out on the day, all clutching attic heirlooms wrapped in bubble-wrap or old blankets, and there had been a good mix of decent finds, honest near-misses and laughable junk. That last part was vital for the show’s comedy twist, which its creators hoped would be their ticket to the international franchising jackpot.

And now she was in Suffolk, standing outside the disused church they were using for the shoot, welcoming and directing the would-be participants. Above her, with his bronze, frock-coated back to her, the town’s most famous son stood contemplating them too, brush in one hand, palette in the other, as if he were about to commit them to canvas. Not that Thomas Gainsborough ever had any interest in such a composition: it was far too urban, from what Gemma had seen of his work in her preparatory research. Comely peasants at woodland cottage doors were more his thing; these pensioners in headscarves and anoraks, clutching takeaway coffee from Greggs were better suited to Lowry or Beryl Cook.

Her main task this morning was triage. That was what Fiammetta, the series producer, called it, but it was an unfamiliar word to Gemma. As far as she was concerned, she was sifting: sorting antiquarian wheat from landfill chaff, with the twist that there was also a perverse premium on the absolute worst of the rubbish.

At first, she had been daunted by the responsibility.

‘I don’t know anything about antiques,’ she protested.

‘Trust me, darling, you’ll know more than Ethel,’ said Fiammetta.

‘Ethel’ was the in-house nickname for the generic punter – elderly, female, under-educated – without whom they would not have a show. The term dripped with snobbery, and Gemma had refrained from using it at first, but she became so used to hearing it that she abandoned her resistance.

‘Just have a look at what they’ve brought,’ said Fiammetta, gold bangles jingling as she hooked a rogue strand of red hair out of her face. ‘Nobody will bring Ming, I promise you, and it will be much easier than you imagine. Think of it as an algorithm. One: is it broken? If yes, it’s junk, if no, it’s still in the running. Two: is it older than you? Seriously, just because they find it in the attic, they think it’s old, and they forget they only moved in ten years ago. If the answer’s no, it’s junk. If yes, it’s still a possible. Three: if you found it, would you take it to Christie’s or the car boot? You’ll know the difference. And that’s all you have to do. After that, it’s up to the experts.’

The ‘experts’ were what counted with a venture such as this. Memorable personalities in the line-up would make all the difference between standing out in the schedules and fading into the mist of daytime mediocrity. To the viewing public, they were the arbiters, the gimlet-eyed professionals who could distinguish at a glance between treasures and dross. In reality, actual expertise was of minor importance. They needed just enough knowledge, or the semblance of it, to be plausible. It would be embarrassing if they were exposed as ignorant, but none of the programme was live, so any such embarrassment could be edited out. Much more important was presence, the kind of quality that made viewers at home think of people on their screens as their friends. Few of those viewers ever grasped what was an axiomatic truth for all those working behind the camera: the qualities that made a TV personality likeable on screen made them largely unbearable in real life.

Britain’s Got Treasures featured four front-of-camera performers. The one with the most TV experience was in the anchor role. Regina Oxenholme, a tiny, ferociously ambitious brunette, was a Channel 5 news presenter with an unfortunate inability to pronounce the letter ‘r’: it came out as a ‘v’, introducing a jarring note into news items about roads, railways, robberies and Russia, but most notably playing havoc with her own first name. She seemed to have no idea she was doing it, and cheerfully complied with requests to introduce herself for every sound-check, oblivious to the hilarity it caused behind the camera.

Of the rest of the ‘talent’, only one had ever appeared on the screen before. Kaz Kareem, the first of the trio of supposed experts, was a midway evictee from one of the last seasons of Big Brother, when even Heat magazine and the Daily Star had lost most of their interest in the tired franchise. Kaz had started his working life on his father’s bric-à-brac stall in Romford. On this basis, he ought at least to have the antique dealer’s gift of the gab, if not the entire knowledge. Unfortunately, he seemed to have spent his whole time on the stall dreaming of escape, and his instincts were more those of a pantomime dame than a market trader. In front of the camera, he had developed a mannered repertoire of eye-rolling and facial jiggling, and had already evolved, through incessant repetition, a catchphrase. ‘But whaddo I know? I’m just a fat poof from Essex!’ he would exclaim, as qualification to every opinion he offered. This self-deprecation worked wonders with Ethel, triggering immediate grandmotherly instincts that transcended more obvious barriers. On a professional level, however, it did not inspire confidence.

The second expert, Lavender Weston-Taylor, was an old friend of Fiammetta’s. She wore mauve suits and ties, had a violet rinse in her grey, bobbed hair, and owned a Georgian townhouse in Spitalfields which was reputedly crammed with eclectica from all eras, with the only proviso that it had to be purple. Gemma at first assumed that this thematic mania was inspired by her name, but in fact the connection was the other way round: Lavender was originally Louise. Her collecting was a qualification of sorts: she had spent thirty years scouring sale-rooms and junk shops, and knew much about many things – so long as they were purple.