Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Lightning Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

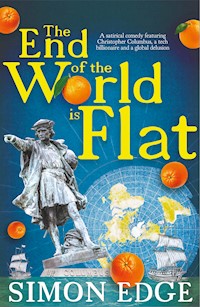

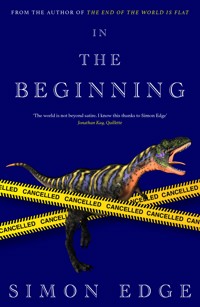

From the author of The End of the World is Flat. 'A coruscating satire on currently trendy anti-science lunacy' Richard Dawkins When Tara Farrier returns to the UK after a long spell as an aid worker in war-torn Yemen, she's hoping for a well-deserved rest. But a cultural battleground has emerged while she's been away, and she's unprepared for the sensitivities of her new colleagues at an international thinktank. A throwaway reference to volcanic activity millions of years ago gets her into hot water and she discovers she belongs to the group reviled by fashionable activists as 'Young Earth Rejecting Fascists', or 'Yerfs'. Faster than she can say 'Tyrannosaurus Rex', she is at the centre of a gruelling legal drama. In the keenly awaited follow-up to his acclaimed The End of the World is Flat, Simon Edge stabs once again at modern crank beliefs and herd behaviour with stiletto-sharp satire.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 473

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Praise for The End of the World is Flat

‘Simon Edge wears his anger remarkably lightly as he skewers the shocking state of the trans rights row with some nifty, often snort-inducingly funny satire’

The Times

‘This sparkling little comic novel is more than playful: it’s a satire of Swiftian ferocity, a thinly veiled parody of a prevailing madness of the hour’

Matthew Parris

‘In between punching the air and shouting “yes!”, I laughed so hard I nearly fell in my cauldron. A masterpiece’

Julie Bindel

‘A satire that skewers the insanity of gender-identity ideology with the wit and brilliance of a modern-day Swift’

Helen Joyce, author of Trans: When Ideology Meets Reality

‘A biting satire’

Andrew Doyle

‘A bracingly sharp satire on the sleep of reason and the tyranny of twaddle. Simon Edge reveals how extraordinary delusions have the power to captivate us – until, one by one, we start coming to our senses’

Francis Wheen

‘Inspired… Edge has glorious, madcap fun…doing what Aristophanes thought poets should do in circumstances like these: save the city from itself. He holds social foibles and cod science up to ridicule with grace, wit and charm’

Helen Dale, The Critic

‘A highly-entertaining satire about ideology, social media manipulation, and lobbying fiefdoms that have overstayed their welcome. This is Animal Farm for the era of gender lunacy, with jokes’

Jane Harris

‘This witty author mixes history with a hilarious spoof of identity politics, virtue signalling, cancel culture and Twitter pile-ons’

Saga Magazine

‘A clever satire on the folly that ensues when a once-respected charity abandons principle and reason’

Joanna Cherry MP

‘I’ve loved every novel by Simon Edge but this one’s probably the best to date. Very clever, very pertinent – most importantly, funny and very humane’

Julia Llewellyn Smith

‘Very, very funny. It’s also way too convincing as a horror story – a completely believable account of how this kind of ideology could seep into great institutions. And possibly, in another form, did’

Gillian Philip

‘Well-crafted, humane and engaging. More than a clever jab at trans ideology, it’s a modern morality tale charting one man’s descent into lies, and a warning about the vulnerability of the liberal values upon which modern society rests’

Jo Bartosch, Lesbian & Gay News

‘Without mercy, this merry romp punctures the idiocy that would turn language and good sense upside down and try to divide us all into either true believers or bigots’

Simon Fanshawe

‘This very, very interesting book about the flat-earthers of the world’

Mike Graham, Talk Radio

‘Turns out I’ve been proven wrong: the world is not beyond satire. I know this thanks to Simon Edge and his very funny book’

Jonathan Kay, Quillette

‘Wonderful. A must-read for all’

Julian Vigo, Savage Minds

‘In a refreshingly pointed reflection on the zeitgeist – a light-hearted lampoon, underpinned with wit and intelligence – Edge crafts an entirely conceivable plot, a parody that is awkwardly close to reality’

Yorkshire Times

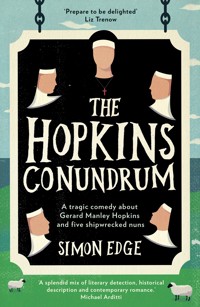

Simon Edge read philosophy at Cambridge and was editor of the revered London paper Capital Gay before becoming a gossip columnist on the Evening Standard and then, for many years, a feature writer on the Daily Express. He is the author of five previous novels, including The Hopkins Conundrum and The End of the World is Flat. He was married to Ezio Alessandroni, who died of cancer in 2017. He lives in Suffolk.

Published in 2023

by Lightning Books Ltd

Imprint of Eye Books Ltd

29A Barrow Street

Much Wenlock

Shropshire

TF13 6EN

www.lightning-books.com

Copyright © Simon Edge 2023

Cover by Ifan Bates

Typeset in Bembo, Academy Engraved and Helvetica Neue

The moral right of the author has been asserted. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

Google is the trademark of Google LLC

Twitter is the trademark of Twitter, Inc

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 9781785633546

What [Mr Bryan] wants is that his ideas, his interpretations and beliefs should be made mandatory. When Mr Darrow talks of bigotry he talks of that. Bigotry seeks to make opinions and beliefs mandatoryChicago Tribune on the Scopes Monkey Trial, 17 July 1925

Dedicated to everyone who has taken a risk to resist the crazy, and especially to ‘Tara’, ‘Helen’, ‘Rita’ and ‘Emily’

Contents

BEFORE THE BEGINNING

AFTERWORD

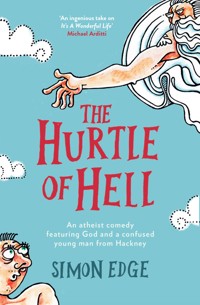

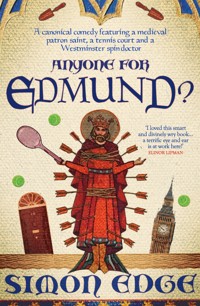

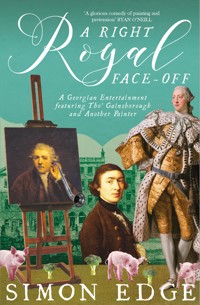

By the same author

BEFORE THE BEGINNING

Polly arrived at the library on the stroke of seven o’clock and slid into her usual seat in the meeting room upstairs, just as Elias, the teacher, cleared his throat and stood up to address the class.

‘This evening I’d like to do another spontaneous writing exercise,’ he said. ‘Here and now. Each of you should work on your own, individually. And for the subject, I’d like you to devise a creation myth.’

‘A what?’ whispered Harmony, an older woman, who always sat near Polly at the rear of the room and often struggled to hear what Elias said.

‘A creation myth,’ their teacher repeated, louder. ‘Is everyone clear what I mean by that?’

A few heads nodded, but not all. Elias beamed at his students. He did that a lot, Polly had noticed. Perhaps it was a cover for nervousness.

‘I mean an origin story for the world around us,’ he said. ‘All religions have them, don’t they? In the Christian tradition, God created heaven and earth in six days, rested on the seventh, then he created Adam in the Garden of Eden, and Eve from Adam’s rib; after that came Cain and Abel, Noah’s Ark, yada yada yada. The Ancient Greeks believed that three primordial deities sprang forth out of chaos and gave birth to all the other gods. In Africa and Asia there were all kinds of other myths, and so on. Right?’

‘Right,’ someone said.

‘So I’d like you to write your own. Some explanation for how the world around us came into existence. It can be as off-the-wall as you like. Really let your imagination fly.’

Sophie, who sat near the front and always took everything literally, raised her hand. ‘Can we do the Big Bang?’

True to form, Elias beamed, even though he obviously thought it was a stupid idea. ‘You can do whatever you like. Try and make it creative, though. This isn’t a physics class. We’re doing what it says on the tin tonight. Creative writing about creation.’

Someone obliged him by laughing, but not Polly. She wanted to raise her hand and ask a question. What are we going to learn from this? That sounded harsh but, six weeks into this course, she was beginning to think Elias wasn’t a very good teacher. After all, this wasn’t a proper college. Just an evening class run by the borough. And when she’d googled ‘Elias Vasiliou’ all she could find was a self-published collection of short stories that had just two reviews on Amazon, both of them three stars. Polly was by no means convinced this guy was qualified to run a creative writing course.

‘Is everybody clear?’ Elias was saying. ‘Good. In that case, off you go. You’ve got forty minutes, and then at the end we’ll read a couple of them out, so we can critique them.’

All the heads went down. Polly glowered at the exercise pad in front of her. For the moment, all she could think of was Elias’ lesson plan. Make them write something: 40 mins. Brilliant for him; only another hour or so to fill at the end. She sighed and tried to focus. Since she had paid for this course in advance, she might as well enter into the spirit. But, as she doodled on her pad, then set down her pen, she couldn’t help seething, silently. This teacher’s main aim in these sessions was apparently to be as upbeat as possible. He encouraged every member of their group of would-be writers with elaborate praise, whether they deserved it or not. That was all well and good, she thought, because who didn’t need their ego boosting? But Elias didn’t seem to know the difference between good work and bad. And the writing exercises he set were often dull.

This assignment, for instance, just seemed stupid. What was the point in stories that were obviously wrong? Sure, primitive people had to make sense of the world around them, and the stories they told themselves made sense in the absence of anything better. But to Polly, such tales had no function in the modern world. For starters, wasn’t putting naivety on a pedestal a bit patronising? And pretending to write in the same way was doubly so: like grown adults trying to paint in the manner of small children, with splodgy lines and no sense of perspective. What was the point?

She felt like saying something, speaking up, making some objection. But instead, she said nothing. She didn’t want to be the troublemaker, the class whinger. She had already tested the waters with a couple of her fellow students, asking cautiously after class what they thought of their teacher, but they’d all said he was great, so there was probably no mileage in moaning out loud. She might as well just do this silly exercise. She sighed, picked up her pen once more, and began to write. Actually, once she started, it wasn’t so bad. She wrote one line and then the next, and ended up becoming so absorbed in the world she was creating that she lost all track of time and jumped when Elias called out: ‘That’s it. All done? Just finish the sentence you’re writing. Don’t worry; it doesn’t matter if you haven’t got to the end. This is mainly an exercise in letting your creative juices flow. It’s about casting inhibition aside.’

And killing time so you don’t have to do any teaching.

Polly dropped her pen on the desk, and looked around at the other students, but nobody returned her gaze. Harmony was still scribbling frantically. Sophie scored something out on her notepad and then went back to examining her split ends.

‘Now,’ said Elias. ‘Who’d like to read their work to the group? Polly? We haven’t heard from you for a while.’

She groaned inwardly. She dreaded being put on the spot at the best of times, but today more than ever. She had written fast and covered several sides of paper, but she was pretty sure it was cringe-worthy.

‘It’s very scrappy,’ she mumbled.

Elias beamed at her. ‘That’s fine. Nobody expects it to be polished.’

She considered saying she couldn’t read her own handwriting, but he would never believe her. In the absence of any other visible escape route, she began to read: ‘In the beginning, there were only the gods. There was an–’

‘Sorry to interrupt, Polly.’ It was Elias again. ‘Can you speak up a bit so everyone can hear?’

Raising her voice, and scarcely bothering to conceal the irritation from it, she resumed: ‘In the beginning, there were only the gods. There was an ancient father of the heavens, and an equally ancient mother, and they were tired, even at the dawn of time, so they tended mainly to nap. That left a large, sprawling family of siblings, doing all the things that messy families do: bickering, wrangling, nursing grievances and pursuing rivalries, while deep down depending entirely on each other. Their names were long, complicated and hard for mortals to pronounce, so I will tell you about just one of them, whose name, Ctat…’

Polly stumbled; if she’d known she had to read this nonsense aloud, she’d have chosen something simpler.

‘Ctatp… Ctatpeshirahi was no less of a mouthful than those of her brothers and sisters. She was known as the potter goddess, because she spent all day turning clay on a wheel, throwing goblets and bowls that none of the other gods ever admired or wanted to use, because they were an entitled bunch with no eye for ceramics. So one day Ctatpeshirahi…’

She was getting the hang of it now, having resolved to leave the ‘C’ silent.

‘…decided she wanted to make something more ambitious than pots. She set about making a clay sphere. She smoothed the sides, proud of her neat finish, then started to shape her globe, pinching up peaks and scooping out troughs so that every spot on the surface was different. After many hours she was pleased with what she had done, and she offered it to her brothers and sisters to admire. They, true to form, showed no interest at all, which upset Ctatpeshirahi.

‘She brooded for a while, then came to a decision: if her fellow gods didn’t appreciate this beautiful world she had created, then she would populate it with beasts and fowl and fish, each in their domain, and they would enjoy it. She looked around for more materials, but she had used up all her clay. This made her despondent at first but then she had a brainwave: she would make these living creatures from her own living body. From the clippings of her fingernails she made the beasts. From the clippings of her toenails she made the fowl. From a strand of her hair she made the fish. And to lord it over these creatures, she made woman, from a drop of her menstrual blood.

‘But woman could not walk the earth alone, because she was mortal and must reproduce if her race were to continue. The goddess pondered this for a moment, then she squatted on a patch of sand to make water. She picked up a clod of this dampened ground and fashioned from it the form of a man, to serve and to fertilise the woman. Then she rubbed her hands together to make fire, and last of all she used spit from her mouth to make the oceans, and thus – nine thousand, nine hundred and ninety-nine years ago – the world was born.’

Relieved to have reached the end, she looked up at Elias. ‘That’s it.’

‘Thank you, Polly,’ said their teacher, putting his hands together in a namaste sign. His voice had dropped to a whisper. ‘Reactions? Yes, Marieke?’

‘Oh…like…wow.’

Polly risked a glance at Marieke from the corner of her eye. A vocal Dutch woman with frighteningly good English, Marieke was the star of the class. She was surely taking the mick. But her eyes shone.

‘That was amazing,’ she said. ‘So imaginative. I love that you turned the patriarchy on its head.’

Other people nodded.

‘I loved the toenail clippings. And the squatting to make water,’ said Shantelle, who was tall and wide and had an infectious cackle. ‘That really cracked me up.’

‘Right? Puts us in our place, eh, Freddie?’ said Elias.

Freddie, fleshy, with a clammy pallor, was the only other man in the room. He shifted uncomfortably from one buttock to the other as attention turned his way, but then it moved on and someone else added their own gush.

‘I really liked the squabbling gods and goddesses. You know, like an actual family? And how did you come up with that amazing name? It sounds, I don’t know, Aztec or something?’

Polly was amazed they were so impressed with all her cheesiest touches. Her unsayable jumble of letters was actually an anagram, but they didn’t need to know that.

Once they had all finally said their piece, there remained time for three others to read their stories out. Each was shorter than Polly’s and, as far as she could tell, almost as bad. She really hated this hippie-dippy New Age crap they had all managed to churn out.

At the end of the class, as everyone handed their work in and filed out of the room, Elias took her aside.

‘That really was a wonderful piece of writing, Polly. By far the best thing you’ve done here.’ He dropped his voice lest the last few stragglers should overhear. ‘Or that anyone has done, to be honest. You should be proud.’

Polly reddened, which he would doubtless take as a blush of modesty. In fact she was thinking of the assignments she had laboured over at home, such as her angry comic riff on the traffic jams all round the north of the borough, caused by the diversions for the Olympics. Genuinely proud of that, she was more convinced than ever that Elias didn’t know what he was talking about.

Oblivious to what she was thinking, he carried on in the same confidential tone. ‘I’ve been asked to put the best work from the course on the library website when we get to the end of the year. Just two or three pieces. I want this to be one of them.’

‘Really?’ Her inner cringe returned. ‘Maybe I can work on it some more so that–’

He shook his head to cut her off. ‘Don’t change a word. It’s perfect as it is.’ He patted the sheaf of papers in his hand, which included her own scrawl.

‘Don’t you at least want me to type it up?’

‘No, don’t worry about that. It won’t take me long to input. I’ll enjoy doing it.’

Polly continued to frown. ‘You won’t use my name, though, will you?’

He stared at her in surprise. ‘Why ever not? You’re a very creative person, Polly. You mustn’t be modest about your work.’

‘No, honestly,’ she said, her resolve hardening. ‘There are, well, reasons why… It’s personal and I’d rather not go into detail, but I try hard to keep my name off the internet.’ Let him believe she was being stalked, if he wanted, or in witness protection. That was nonsense, but she was adamant: she would not be identified as the author of work she hated.

He pursed his lips. ‘Got it. We’ll make you anonymous. And well done again.’

Polly turned away so he couldn’t see her eye-roll.

As she headed downstairs, she wondered for a moment if the class were right and she really had written something of value. Then she reminded herself that the simplest explanation was usually the best: no one in the group was any good, even Marieke, and they were all fools to put any faith in Elias.

By the time she emerged into the warm evening, she knew she wouldn’t come back for the rest of the course. And she would rather stick pins in her eyeballs than ever look for her own creation myth on the library website.

1

Tara Farrier closed the door of her flat for the last time, pulling it hard towards her to be able to turn the key, and descended the two flights of stairs to her landlord’s apartment on the ground floor of the dilapidated building. A smell of frying onions hung in the stairwell. It was not yet ten o’clock but Badiya, her landlord’s wife, had evidently made a start on lunch.

The door of the lower apartment opened a crack before she had a chance to knock, revealing the impossibly wide, moss-green eyes of four-year-old Hassan.

‘Sabah al-kheir,’ said Tara, smiling down at him.

‘Sabah an-nour,’ whispered the boy shyly, the ritual response to the morning greeting.

‘Is your father in, sweetie?’ Tara continued, still in Arabic. It was technically her mother tongue and, after seven years here in Yemen, she spoke it as naturally as English.

Hassan shook his head solemnly.

Above his head, two more eyes appeared, peering warily out. Once she had satisfied herself that Tara was alone, Hassan’s mother opened the door properly. She wore a full-length black abayathat hid the contours of her body, her face framed by a matching scarf. She held the door open with her left hand while cradling an eight-month baby – her fifth child, and unlikely to be her last – in the crook of her right arm.

She smiled. ‘Come in,’ she said, reaching out to try to pull Tara over the threshold.

But Tara didn’t have time. ‘Thank you, I can’t.’

‘Come in. Drink a cup of coffee.’

‘Thank you, I’ve already drunk one.’

‘Come in,’ urged Badiya a third time, but without much hope.

This, like the pairing of the greeting and response for ‘good morning’, was part of the ritual. Newcomers to these parts were always thrown by it, accepting the first invitation without realising it was bad form to do so until you’d been asked three times.

‘I’m sorry, my sister,’ said Tara. ‘I have to get to the airport.’

‘What time is your flight?’

‘Two and a half hours from now, God willing.’ In sha’ allah. That was another lesson she had learned early in her time in the Arab world: with any question about the future, the will of God – even one in whom Tara had never believed – must always be invoked. Are you going to the market this afternoon? In sha’ allah. Are you seeing your foreigner friends tomorrow? In sha’ allah. After a while it became second nature and Tara had no cause to object, because who in this benighted country could say anything for certain about the future? Especially in matters concerning Aden’s battered airport, a casualty of the civil war, and only just back in operation after three years of enforced closure. Even now, no more than six flights arrived and departed every week. Any traveller who thought they could get off the ground without divine assistance or a massive chunk of luck was in for a rude awakening.

‘But two and a half hours is long and the airport is very near. You have time.’

Tara raised her chin and clicked her tongue, emphasising her refusal; these physical gestures were as much a part of the language as the words. ‘There are controls. Passport, luggage, all these things. It takes time. And perhaps there will be a checkpoint on the road.’

Badiya shrugged, unconvinced.

But Tara meant it. With so few routes out of the country, she couldn’t afford to leave anything to chance. ‘Here’s my key,’ she said. ‘Will you give it to Ahmad? Say goodbye to him for me, and to the other children. Thank you all for everything in these past few years.’

Tears rolled down Badiya’s cheeks now, and the two women hugged.

‘Now I’ve started too,’ sniffed Tara, laughing at herself as she mopped her eyes with the back of her sleeve. She’d been saying her goodbyes all week and each one was harder than the last. But she was doing the right thing, she reminded herself, as she kissed Badiya on both cheeks and waved at Hassan from the little path that led to the street.

Mansour, her driver for most of the past seven years, was waiting beside his dusty, battered Hilux, wearing his customary wrap-around sarong – known as a futa in this part of the world – and with his chequered keffiyeh piled on his head. He had already stowed her luggage in the pick-up’s rear section.

‘Ready, madam?’

She had tried to talk him out of such formality, but dropping it clearly made him uncomfortable, so she’d given up trying.

‘As ready as I’ll ever be,’ she sighed, climbing into the back seat. Of all her friends in this country, she probably had the greatest affection for this under-educated but smart and gentle man with whom she had spent so many hours on the road. This last parting would be the toughest.

With Umm Kulthum wailing plaintively on the car’s music system, the vehicle pulled out in the direction of Marine Drive and the airport. ‘Why do you have to go?’ Mansour’s eyes in the rear-view mirror looked tired and sad.

They’d had this conversation many times since she’d broken the news.

‘You know why, my brother. I’m next to useless here. Back in England, perhaps I can advocate for an end to the bombings and the blockades. Maybe I won’t succeed, but I have to try.’

They passed under the portrait of the city’s former governor, assassinated in the first year of the war. Traffic on the dual carriageway was light. Fuel shortages had forced most petrol vehicles off the road. A small boy on an even smaller bicycle careened alarmingly in front of them, waving his hand dismissively as Mansour honked his horn.

‘How many hours to London?’ Mansour asked.

‘Too many. First I have to go to Cairo, which takes three and a half hours, then another five to London, with a long wait in between. Two hours, I think. How many is that?’

‘Very many. But when you arrive, you will see your children.’ He smiled encouragement, revealing teeth stained the colour of teak. She had been shocked at first to see the dental damage wrought by daily qat chewing, but now she barely noticed.

‘And I’ll see my children. Very true.’

Of course she saw them regularly on Zype, whenever the internet was working. But it was two years since she had seen Laila and Sammy – both now adults, not children – in the flesh. Back then, she had made the twelve-hour journey across the empty desert to Seiyoun, which was the country’s only functioning airport at the time, and hopped over to Djibouti, then to Paris and London. At least today’s flight would be more straightforward. In sha’ allah.

‘They will be so happy to see you,’ said Mansour.

Tara laughed, because people in this part of the world had no idea how casual an English family could be. ‘It will be lovely to see them, but they’re both very busy with their jobs.’

The Hilux had arrived at the cluster of oil drums that marked the checkpoint at the perimeter of the airport. In the distance, Tara could see the huge hole blasted out of the wall of the arrivals terminal, a grim reminder of the mortar attack two years earlier on a plane carrying an entire cabinet-in-exile. She scrabbled in her bag for her passport, ready to show the teenage soldier now peering into the back of the car.

Mansour shrugged, as the teenager returned the document and waved them on. ‘Never mind. You will also be busy with your work, no?’

‘In sha’ allah,’ said Tara.

Of course he was right. Going home was an upheaval, and her heart ached at having to leave this ramshackle, wounded, dysfunctional place. But she intended to plunge into her new job, and to make a difference, because that was what mattered.

2

As the plane began its approach to Heathrow, Tara removed the headscarf she had worn as second nature in Yemen. All around her, Arab women were doing the same. Boarding the flight in Cairo, they had all been draped in shapeless abayas, with their hair covered, and some of them veiled. But one by one they had made their way to the lavatory and returned in jeans, tight tops and lipstick. It was part of the ritual of visiting the West. No wonder they looked so excited.

Tara was excited now too. Traumatic as it had been to uproot from the place she’d called home these past seven years, she had plenty to look forward to on her return home – starting at the airport, where Laila had promised to meet her. For all Tara’s own earlier cynicism, Mansour was right: her children did seem pleased to have her coming back to them. It took forever to get through arrivals and retrieve her luggage, but there her daughter was, waving at the gate.

‘Hamdillah as-salama,’ said Laila as they hugged. Thank God for your safe arrival. She, more than her brother, had a smattering of Arabic from childhood and she knew all the ritual phrases.

‘Allah yisalmik,’ laughed Tara, in the obligatory reply.

‘How was your flight? Have you slept? Here, let me take one of those bags for you. We’re in the short stay, over here. If we hurry, we’ll only have to pay for forty-five minutes not an hour. Can you believe they charge in quarter-hour increments? It’s such a rip-off.’

Tara struggled to keep up with her daughter’s stride. ‘Don’t worry, I’m paying.’

Laila grinned. ‘Yeah, that kind of went without saying.’

She was smaller than Tara, with the same chestnut hair, but grey eyes, from her father’s side, and wider at the hip than Tara had ever been. Better that, though, than anorexic, pinching at lettuce leaves and fretting about her beach body, like so many of her generation.

Tara shivered as they emerged from the air-conditioned terminal into the grey morning air. ‘Ya allah, it’s cold.’ She drew around her the coat that she had pulled from her suitcase at the carousel. It had spent seven years in her cupboard in Aden solely for this journey.

‘This is mild for February. You should have seen it last week. We had snow.’

Tara shuddered at the thought.

Every visit home had been weird. If it wasn’t the weather, it was the culture shock of an affluent country. New cars, properly surfaced roads, no bomb-sites or burned-out tanks left to rot in the roadside scrub. And nobody stared, because Tara was no longer a paler-skinned foreigner in a land where few foreigners came, or the only woman not wearing an abaya.

She paid the parking charge at the machine as Laila loaded her bags into the boot of the car.

‘Did you sleep on the flight?’ her daughter asked again, as they nosed down the ramp and out into the airport road system.

‘On and off, I guess. Enough to keep going till tonight, provided I can make some decent coffee as soon as we get home. There is coffee, isn’t there?’

‘Don’t worry, I’ve done some shopping for you. I even bought cardamom. I know how fussy you are.’

Tara clapped her hands with delight. ‘What a welcome. Thank you, habibti. You think of everything. And you must let me pay you back.’

‘Don’t worry about that. I didn’t get, like, that much.’ They emerged from the airport perimeter and joined the motorway approach road. ‘So tell me, what’s your plan now? When do you start your new job? I hope you’re at least having a break first.’

‘I can’t, habibti. They want me to begin as soon as possible. Besides, it wouldn’t feel right to be sitting around doing nothing while…’ She tailed off.

‘While there’s a war on? I get that, Mum. But let’s face it, the war will still be going on next week, and the week after that. You need to recharge your batteries, otherwise you’re no good to anyone.’

‘Charming.’

‘You know what I mean.’

‘I do know what you mean, but the fact remains that my new boss wants me to start immediately. As soon as I get home, I’ll have to work out how to get to the new office.’

‘You’re actually going into the office?’

‘Yes of course. Why wouldn’t I?’

‘These days loads of people work from home. I just assumed you would too, rather than trailing all the way into London. It is in London, right?’

‘Yes. Somewhere just off the Strand, I think. I don’t mind going in. I’m looking forward to getting to know my colleagues. They’ll all be much younger than me, but that will be stimulating.’

‘If you say so. All my colleagues are much younger than you too, but stimulating isn’t the word that comes to mind.’ Laila worked for the council in Canterbury and spent most of their Zype time complaining about it. Tara hoped she was more charitable to her workmates than she affected to be.

‘You always see the worst in everyone. You get that from your father.’

‘Thanks. I’ll tell him that.’

‘Don’t you dare.’

Rain lashed the windscreen on the M25, and Laila notched the wipers into frantic mode, but the sky had cleared by the time they spurred off into Kent.

‘Look, the sun’s come out for you,’ she said as they passed Stourbourne station.

Little seemed to have changed in the village centre, apart from yet another estate agent replacing the moth-eaten antique shop, and a fancy-looking butcher instead of the strange hippie outfit that used to sell crystals and incense. But the village itself had grown larger, she saw, as they passed through. Where once had been fields, now stood an estate of new houses, detached, semis and townhouse terraces, all weatherboarded in an attempt at the county vernacular.

Tara’s home, Willow Tree Cottage, stood nearly alone, alongside just one other house, a couple of miles outside the village. Around four hundred years old, according to a date carved into one of the beams, it was finished with whitewashed bricks and proper old weatherboarding, with first-floor gables puncturing a steep, red-tiled roof. She had loved it as soon as she and Doug, her ex-husband, set eyes on it, not least because it stood in an acre of land, which had become Tara’s pride and joy after the divorce. As the car turned in at the gate, she expected to see a jungle, because the recently departed tenants were unlikely to have done much gardening, but all looked remarkably neat.

‘I can’t believe how well they’ve looked after it. I imagined much worse,’ she said.

‘Oh, it was pretty bad,’ her daughter laughed. ‘I told them we’d keep their deposit unless they got a gardener in to tidy it up.’

‘You didn’t! That’s awful. I feel bad enough about giving them notice.’

‘It’s your house. You’ve got the right to live in it. Honestly, Mum, you’re such a soft touch. Renters know they have to look after a place. It’s part of the deal. I’m one of them, so trust me, I know. It’s the way of the world.’

Tara sighed. ‘What about the house itself? How did they leave that?’

‘To my surprise, it was immaculate. I reckon maybe they trashed the place so they had to redecorate.’

‘You’re thinking the worst again. Perhaps they were nice respectful people who just didn’t like gardening.’

‘If you say so. Anyway, here we are. Don’t worry about finding your key, use mine. You let yourself in and I’ll bring your bags. I put the heating on low a couple of days ago, but you may want to turn it up. And I’m sure you’ll want to put that coffee on. You’ll only complain if I make it.’

Tara brewed the coffee in the traditional Arab stove-top way, stirring sugar and cardamom into the pot as she brought it to the boil. Laila stayed for one cup, then went home, promising to check in by phone later. Afterwards, Tara trailed contentedly from room to room, revisiting her inglenook fireplace that was big enough to stand inside, her crooked staircase that had driven the carpet-fitters crazy because no two risers were the same height, her bathroom that she and Doug had tiled themselves with decorative ceramic slabs from Jerusalem. She had forgotten how much she loved her cottage.

All her clothes, her books, her pictures from the walls, and her keepsake clutter, representing a lifetime of memories, had been stowed in the attic and the space above the garage, allowing her tenants to personalise the place in her absence. It would take her days to make the place her own again. Sammy had texted to offer help on that score as soon as he finished work, and he would be a great help with the heavy lifting. But Tara wasn’t in any great hurry to restore everything immediately. She liked the prospect of re-establishing herself slowly, and discovering the paraphernalia of her past piece by piece, rather than racing at it.

Laila had stocked the fridge with milk, cheese, live yoghurt, eggs, hummus, onions, tomatoes, a pizza and some apples, and there was a fresh loaf on the breadboard along with a bottle of good olive oil on the shelf. Tara would need to do a proper shop, but this covered all her immediate needs.

Even after she had turned the heating up, the chill of the house was a shock. What it really needed was a roaring fire. After tipping out the coffee grounds and washing the pot and cups, she let herself out of the kitchen door to check on the wood-store, more in hope than expectation. Sure enough, the pile had dwindled to nothing. Either the tenants had used all the logs or, perhaps more likely, taken every last twig with them, in revenge for Laila’s heavy-handedness over the garden. She made a mental note to contact old Mr Carter the log-man, who would bring a truckload of seasoned wood and could usually also be persuaded, for a few extra notes, to stack them.

Returning indoors, she turned up the thermostat by another couple of degrees and took her laptop into the dining room, which had the biggest radiator in the house.

Through force of habit, she started by checking the overnight news from Yemen. Three civilians had been killed in the capital, Sana’a, after the rebel Houthi administration shot down a Saudi drone spy plane. A sandstorm followed by heavy rains had caused havoc at several of the displacement camps in the desert outside Marib. Truce talks, as ever, continued.

Reading these stories made Tara feel more disloyal than ever for abandoning her post. On the other hand, those dreadful tragedies would have happened whether she was in the country or not, and it was more important than ever that she use her expertise and influence on the outside, particularly now that she’d been granted a rare opportunity to do so, in the form of her job with the Institute for Worldwide Advancement, a think tank that lobbied the governments of wealthy countries on behalf of the poor.

Fortified by that thought, she navigated to the IWA website. The outfit was headquartered in New York, but its European regional office was in London, at an address in John Adam Street, next to the Adelphi. Handy for Charing Cross. On the site’s header bar, she clicked the ‘people’ tab.

The regional director who had hired her, Matt Tree, was based in New York. His mugshot showed a thickset figure with silver temples and a determined smile. It made him look more like a rough-and-tumble politician or a union boss than the Harvard PhD referenced in his bio, but he’d been soft-spoken and contemplative in their two or three Zype calls.

Her contact in London was Rowan Walker, who remained merely a name so far. Rowan’s bio made it clear she was also an American, with a Cornell degree and a scarily impressive CV involving the Obama-era State Department. Would Tara measure up to these hyper-achievers? It was hard not to imagine them all trotting purposefully along corridors speaking witty, clever, perfectly structured sentences at breakneck speed, like characters from The West Wing. She consoled herself with the observation that Rowan, who looked to be in her mid-forties, had sat for her website portrait on a day when she badly needed her roots retouching. No woman who did that could be entirely awful.

She opened her email programme and typed:

Hi Rowan

Just to let you know I’m safely back in England now, adjusting to the cold (!) and raring to go. The last I heard from Matt, he was keen for me to start immediately too, so I was planning to come into the office tomorrow, if that’s all right with you. Let me know.

Best

Tara

As she pressed send, she drained her coffee and shivered again. She had been sitting still for too long. Shutting the laptop, she began hauling her largest suitcase up the narrow staircase to make a start on her unpacking. She’d planned to wait for Sammy to help her upstairs with it, but there was no time like the present.

An hour later, she had unpacked all her Yemeni luggage, started a load of washing and parcelled up the bits of silverware she’d brought back as gifts. Moving around had warmed her up, but now she flagged as the long journey and lack of decent sleep caught up with her. Standing in the living room doorway, she looked at her familiar old Knole sofa, its wooden bobbles held together with thick rope, and thought how much she’d love to take a nap on it. Even if she had firewood, that would be a bad idea: she firmly believed in pushing on through the tiredness in order to get a proper night’s sleep when the time came. Still, a quick sit down wouldn’t go amiss…

She awoke to a knock at the door. Groggily, she pulled herself up off the sofa and made her way through into cottage’s little hallway. Opening the front door, she saw a tall young man with a dark, unruly beard.

‘Sammy!’ As he stepped forward, she allowed her son to fold her into a hug. ‘Oh I’ve missed you. But I wasn’t expecting you so early. How did you manage to get away?’

Sammy ran the kitchen at a vegan café in Margate. The hours were long, accounting for the bags under his eyes.

‘We close after lunch on Tuesdays. I insisted. It was either that, they hire another chef to support me, or I had a total breakdown. They went for the early closing.’

‘Good for you, but…’ She checked her watch and saw that it was three o’clock. ‘Y’allah, how long have I been asleep?’

He laughed. ‘Sorry, did I wake you? I just thought it was better to come in daylight if we’re getting your stuff out of the garage.’

‘Yes, of course. It’s wonderful to see you. Come in and let me make us some coffee.’

He closed the door behind him and followed her into the kitchen. ‘You are going to run me home when we’re done, aren’t you?’

‘Run you home? Why?’

‘So you can have the car back. I can’t get home otherwise.’

On her departure for Yemen, Tara had let Sammy have her scarlet Fiat 500, on condition he taxed it and paid the MOT. She now saw it through the kitchen window, looking rather more scuffed than she remembered it.

She clicked her tongue at him. ‘I don’t want it back, habibi. It’s yours.’

‘But…how are you going to manage?’

She spooned coffee, cardamom and sugar into her trusty pot, topped it up with water and put it on the stove to boil. ‘I’ll get a new one. Well, not new. I was going to go to the guy in Canterbury who sold me that one. I trust him and he did me a good deal last time.’

‘What will you do in the meantime? Laila said you’re planning on going to London tomorrow, for your new job. How will you get to the station?’

‘Ah, thanks for reminding me. I should just check…’ She looked for her laptop, then remembered it was in the dining room. ‘I just want to see if my new boss has returned my email. Could you grab my laptop for me, habibi? It’s on the dining table.’

He fetched it for her and she logged in, keeping one eye on the coffee so it didn’t boil over. Yes, there was her reply. Hi Tara. Great to have you with us. Do indeed come into the office tomorrow. We normally start at 9.30 but no need to come that early. How about 11? I’ll look forward to meeting you. Best, Rowan.

‘So yes, I am going to London tomorrow,’ she said. ‘But I can cycle to the station, as long as you help me oil the bike and pump up the tyres. I’m looking forward to it, in fact. I haven’t been on a bike in all this time.’

‘Yes, I can do that, if you’re completely sure about the car. Thanks Mum.’

He hugged her again.

‘You’re welcome,’ she said. This was the wonderful thing about having grown-up kids: they gave you plenty of affection, and all you had to do to earn it was bribe them with gifts of cars.

Satisfied that her brew was ready, she poured out two small espresso-sized cups. Sammy blew on his coffee to cool it down, then knocked it back in two or three swigs.

‘I’ve missed that. I really have,’ he said. ‘So where shall we start? Attic or garage?’

3

In Tara’s time away, the railway operator had renewed the rolling-stock on the Stourbourne line. While she knew it was a major breach of commuting etiquette to entertain any positive thoughts about the service, she was impressed. Warm carriages, neat LED displays telling you which stop was coming next, plugs near every seat to charge your phone or laptop: this was first-world luxury. In the country she had come from, public transport was limited to stifling hot buses on chaotic timetables and shared taxis where you were squashed and suffocated with tobacco smoke. The charm quickly wore off.

At Charing Cross station she dawdled, intimidated by the unforgiving stampede of those who did this journey every day and didn’t need to follow the signage or fumble at the barriers. Outside on the Strand, she paused a moment to take London in: timeless, but also constantly mutating. Cyclists had their own traffic lights now. And there were more bikes than ever. In Yemen, cycles were ramshackle affairs, ridden slowly to avoid the potholes, and only by the very young or the very old, or by someone carrying a ladder under his arm. Those riders would no more dream of wearing a helmet than of flying to the moon.

As she watched, a stream of cars and bikes stopped at a red light to let a flow of pedestrians hurry across. The sight made her laugh out loud. After seven years, she was used to crossing roads the Arab way: flinging yourself into the traffic in the reasonable faith that it would brake or swerve, because that was what drivers expected. Note to self: this method would get her killed in London.

The bell of St Martin-in-the-Fields began to chime the hour, prompting her to get a move on. She turned down into Villiers Street, where the old Evening Standard kiosk used to stand, in the days when you paid money to a wizened barker rather than just plucked your free copy from a pile, and then took the first left into stately John Adam Street. She checked off the numbers on the northern side, past the pillared façade of the Royal Society of Arts, till she reached an elegant Georgian five-storey with bowed railings at the full-length sash windows on the first floor, and hanging baskets of yellow-eyed winter pansies over the front door. The IWA didn’t occupy the whole place, as a stack of brass plates confirmed; from the way they were placed, it looked like her destination was somewhere at the top.

Tara pressed the designated buzzer and announced herself.

‘Fourth floor,’ said a disembodied male voice. ‘You can take the lift but I honestly wouldn’t.’

‘That’s fine. I’m glad of the exercise,’ Tara called back, as the door clicked open.

Inside, the building smelled of whatever chemical freshener had been sprayed onto the stair carpet by some invisible team of pre-dawn cleaners. It was a far cry from Badiya’s frying onions, the thought of which stirred a momentary pang of longing, but Tara pushed that out of her mind as she laboured up the unnervingly steep stairs. At least physical activity was easier in this country, where you didn’t have to do it in seventy percent humidity.

At the fourth landing, a fire-door opened into a small, unstaffed reception area, furnished with a couple of Art Deco tub chairs and a coffee table, which was strewn in a purposeful way with IWA publications and back copies of The Economist and Newsweek.

A woman whose face she had seen on the website strode smiling towards her, hand outstretched. She was trim and businesslike in a tailored grey suit.

‘Tara? I’m Rowan. Great to have you with us.’ Her accent was anglicised American, suggesting she’d been here a while. ‘How is it, being back in Blighty?’ The not-quite-colloquialism had a certain Dick Van Dyke energy.

‘Cold, mainly,’ said Tara, returning the handshake. ‘It’s funny: there were plenty of times in the past few years when I yearned to be cold. But now I’m yearning for equatorial heat once more.’

‘The grass is always greener, I guess. Can I get you a cup of coffee before I introduce you to the team?’

Tara told her water was fine.

Rowan disappeared into a kitchenette, re-emerging with a brimming glass, then began her tour of the office. The fourth floor had been hollowed into an open-plan space, while preserving stubs of the previous walls to show where the original rooms had been. The office contained five people other than Rowan. Tara was presented to: Toby (white, bespectacled); Akeem (bearded, bespectacled); Lucy (blonde, expensively spoken); Darcy (Aussie, or maybe South African – it was hard to tell from a one-sentence greeting); and Evelina (glamorous, with a strong Slavic accent). She guessed they were all between ten and twenty years her junior – maybe nearer thirty in Lucy’s case – which was what she’d expected. She herself had reached the age of invisibility, when you were either meant to run the whole show or disappear into homebound semi-retirement. No matter. She would buck that trend with pride.

‘Don’t worry, we won’t be testing you on the names,’ said Rowan, in the time-honoured cliché of such situations. ‘In any case, I know you’ll probably want to work from home most of the time, but you’ll be able to catch up with everyone on Clack. That includes the New York office. They’re all on it too. It’s a brilliant way of bringing us all together.’

It was news to Tara that she’d want to work from home. She bit her lip. ‘Oh right. I’m happy to be in the office, to be honest. I’d welcome the interaction. Unless you–’

‘As you can see, we don’t really have the space,’ Rowan cut in, sweeping her hand around what was indeed a fairly cramped environment, encumbered as it was by far too many heavy bookcases. ‘Most of the people here are actually hot-desking. But we’re hoping to expand upstairs in the not-too-distant future. In the meantime you’re very welcome to come in for our Wednesday lunches. They tend to be our most social time. Otherwise it’s mainly heads down.’

It was true. They’d all seemed friendly enough when shaking her hand and telling her how happy they were to have her aboard, but now they had all returned to their keyboards, several of them behind airpods, tapping silently away.

‘All right. Wednesday lunches. I can do that,’ said Tara, telling herself not to take it personally. ‘And…sorry…Clack?’

‘Don’t you know it? You’ll love it. It’s an internal comms app with loads of different channels. Brilliant for home working. You post messages on particular subjects, and everyone who needs to see them will do. It’s so much better than strings of emails with ass-covering cc’s to everyone under the sun. But it’s also sociable. There’s a general channel where we encourage people to post pics of their holidays or their kids, or to tell us what they’re reading, or just to have debates on any issue that grabs them. That’s our ethos here: share, discuss, don’t hold back.’

‘Great. I won’t,’ said Tara. It sounded a peculiar notion, but if this was the way of the modern office, she could certainly post some pictures of Yemen. Her new colleagues all knew it was a war zone, but she’d lay odds that none of them had the slightest idea of its extraordinary cultural heritage, its unique architecture, its natural beauty.

‘Take a seat.’ Rowan led the way to her own desk under a window at the front of the building, and gestured at a spare chair. ‘So, it’s exciting to have you join the team. Matt and I had a chat yesterday, and we’d like you initially to focus entirely on a country report, calling on both your academic expertise and your experience on the ground. We’re hoping you can create something both definitive and punchy, to help us rebrand this conflict. At the moment the Yemeni civil war is a problem in a faraway land that has nothing to do with us and is too complicated to understand. We need to change that, to reframe it as a political and humanitarian priority that no Western legislator can ignore, where the issues are simple: weapons supplied by rich countries are being used to bomb the hell out of one of the poorest countries on earth, and they shouldn’t be. How does that sound? Tall order, or doable?’

Tara smiled. ‘It is a tall order, but if I didn’t think it was doable, I wouldn’t have flown five thousand miles from the land of frankincense and myrrh to a miserable English winter.’

‘Frankincense and myrrh, exactly! Write about that stuff. Lots of positive cultural things to bring the place alive. Didn’t I read that it was originally ruled by the Queen of Sheba? I’m not sure I even know who the Queen of Sheba was, but everyone has heard of her, right?’