Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

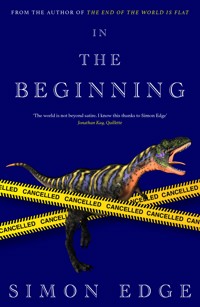

- Herausgeber: Lightning Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

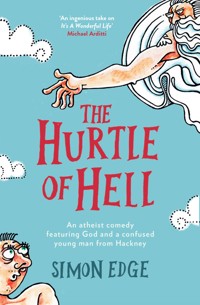

An atheist comedy featuring God and a confused young man from Hackney. When gay, pleasure-seeking Stefano Cartwright is almost killed by a wave while at the beach, his journey up a tunnel of light convinces him that God exists after all, and he may need to change his ways if he is not to end up in hell. When God happens to look down his celestial telescope and see Stefano, he is obliged to pay unprecedented attention to an obscure planet in a distant galaxy, and ends up on the greatest adventure of his multi-eon existence. The Hurtle of Hell combines a tender, human story of rejection and reconnection with an utterly original and often very funny theological thought-experiment, in an entrancing fable that is both mischievous and big-hearted.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 413

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

‘Simon Edge is a stunning new voice’

Foreword Reviews

Gay, pleasure-seeking Stefano Cartwright is almost killed by a wave on a holiday beach. His journey up a tunnel of light convinces him that God exists after all, and he may need to change his ways if he is not to end up in hell.

When God happens to look down his celestial telescope and see Stefano, he is obliged to pay unprecedented attention to an obscure planet in a distant galaxy, and ends up on the greatest adventure of his multi-aeon existence.

The Hurtle of Hell combines a tender, human story of rejection and reconnection with an utterly original and often very funny theological thought-experiment, in an entrancing fable that is both mischievous and big-hearted.

‘A sparkling mixture of domestic and celestial comedy. A conflicted gay man meets his bungling creator in an ingenious take on It’s A Wonderful Life’

Michael Arditti

Simon Edge was born in Chester and read philosophy at Cambridge before working as a journalist for many years. He has taught creative writing at City University and lives in Suffolk. This is his second novel.

Published by

Lightning Books Ltd

Imprint of EyeStorm Media

312 Uxbridge Road

Rickmansworth

Hertfordshire

WD3 8YL

www.lightning-books.com

First Edition 2018

Copyright © Simon Edge

Cover design by Anna Morrison, original artwork by David Shenton

All rights reserved. Apart from brief extracts for the purpose of review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without permission of the publisher.

Simon Edge has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as author of this work.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Printed by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY

ISBN: 9781785630712

For my late parents, Myles and Kathleen Edge

The frown of his face

Before me, the hurtle of hell

Behind, where, where was a, where was a place?

I whirled out wings that spell

And fled with a fling of the heart to the heart of the Host.

My heart, but you were dovewinged, I can tell,

Carrier-witted, I am bold to boast,

To flash from the flame to the flame then, tower from the grace to the grace

Gerard Manley Hopkins

The Wreck of the Deutschland

Contents

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

Afterword

1

Stefano must have blacked out. When he came round, he was looking down on an agitated crowd. They were clustered around something lying on the dark, wet sand, just clear of the waves. At the centre of the gathering crouched a squat, middle-aged man in improbably tiny Speedos, buttocks in the air. Bent over the body of a pale young man, he was trying to give him the kiss of life. The poor bastard, thought Stefano uncharitably. He would get a shock if he came round to find that guy sucking his face.

Craning to get a better look, it occurred to him that the stricken swimmer’s candy-striped trunks looked familiar. Now he realised that so was the body, which really was shamefully pallid compared to all the bronzed onlookers. It was superficial to be so critical, but Stefano had every right, because that was his own body he was looking down at. That was him, lying there on the beach.

This was like the weirdest dream he had ever had, but he somehow knew, as surely as he had ever known anything, that this was not a dream. This was happening.

He watched the kiss-of-life guy come up for air, puffing it in with a great gulp, and then hunch over for another attempt. The scene was silent, and it took Stefano a moment to grasp that this was not because nobody was talking, but because he could not hear. There must still be water in his ears after being pulled under like that. If only his rescuer would stop the kissing thing for a moment and tilt his head from side to side, it might drain out.

He could see the onlookers’ mouths moving as they jostled inwards. Now someone – Stefano recognised the soft-drinks seller who hawked Coca Cola from a cart in the middle of the beach – pushed them back. Give him some air, he would be saying, because that was what people always said in situations like this, only he would be saying it in Spanish, and Stefano had no idea what that was. And there, finally, was Adam, with only a hint of anxiety at first, turning abruptly to panic. Stefano did not need to lip-read to know that his own name was being shouted.

Then, abruptly, the scene was gone. He could no longer see himself, nor any of the people around him, and he was surrounded by specks of white light. As his eyes adjusted to the brightness, he saw that he was in some kind of tube. Not that he could see the sides – the lightness was everywhere and nowhere – but it felt like some kind of extraordinary tunnel because it was brighter up ahead, and now he was conscious of rising towards the far end of it. He felt light-headed, euphoric, as if the whiteness were shining inside him. It reminded him of the first rush of a pill, in the days when they still worked and you knew why it was called ecstasy, only there was nothing illicit about this. What was happening to him? As he rose further and further up the long, white cylinder he was curious about what he would find at the end, but he felt no fear.

He blinked to focus better as the white walls rushed past him. There was definitely something up there now, different from the shining white, covering the entire end of the tunnel. His attention was drawn in particular to a pinpoint of pitch black at the centre, which gradually widened as he came closer. Now it became a deep, inky pit that he seemed to be moving steadily towards, a black hole at the end of the white corridor. All around the edges of this hole straggled translucent rivulets of white and grey, coursing over a glistening blue ground and pouring into the black abyss like water into a well. Beyond these shining trails of white, he saw, was something else: a border, like smooth rocks circling the pool of rivulets. Or maybe it was softer…porous, organic, alive.

It looked like an eyelid, he suddenly realised: the black hole was a giant pupil, the straggling rivulets over a shining blue ground were the iris, and that giant lid must belong to…

‘He’s breathing!’ shouted someone, disturbing his concentration, and he heard a painful rasping sound accompanied by exclamations of relief. He blinked his eyes open, which was odd, because he could have sworn they were open already, and found he was looking at the kiss-of-life guy again, not from above this time, but from his own body, flat on the wet sand. He could hear again, that was for sure, and the rasping was coming from his own throat as he coughed up brackish sea water. The kiss-of-life guy smiled. With his wide, fat lips and gappy teeth, he reminded Stefano of a kindly toad. Then the face was replaced by an even more welcome one.

‘I thought I’d lost you,’ said Adam, and Stefano could see he was trying not to cry. ‘How do you feel? Don’t try to talk. We need to get you to a hospital. Can we get him to a hospital?’

Someone was shouting Spanish into a mobile phone. Adam kept turning away to talk to people, and it seemed an age before he was paying attention to Stefano again and there was a chance to tell him. To try to tell him, at any rate – it was hard to breathe, let alone talk, and his whole head stung with salt.

‘Don’t try to speak,’ said Adam. ‘Just stay there for the moment and then we’ll get you to hospital. No, you mustn’t try to move. Please, lie still.’

Stefano tried again to reach for Adam’s hand, finding it this time and attempting to pull him closer. ‘You don’t understand,’ he was saying in his head, only it would not come out like that. It would barely come out at all. But he kept trying, and Adam was eventually forced to stop shushing him and lean in close to make out what he wanted to say.

‘I think…’ said Stefano at length, concentrating hard to make the words separate themselves from one another.

‘Yes? What?’

‘I think I just saw the eye of God.’

2

The holiday on this strange little volcanic island had been Adam’s idea. They had started on the opposite coast, under a blanket of cloud. There were no beaches on that side, and the bad weather seemed so permanent that it was even cloudy in the postcards.

As the outermost part of the archipelago, the island had been celebrated in ancient times as the edge of the known world. This excited Adam. For someone who had always been interested in astronomy, the further discovery that this had once been the zero meridian, where the western and eastern hemispheres officially met, made the place all the more evocative.

Unfortunately, soaking up this conceptual geographical history was not Stefano’s idea of a good holiday, especially when it rained ceaselessly on the day they trekked to the lighthouse that marked the western tip of the rock. There was not much to see, and Stefano was conspicuously unimpressed.

‘There’s not even a plaque,’ he observed, after circling the lighthouse twice.

‘What do you want it to say? This used to be the edge of the world and now it’s not?’

‘It feels like it still is.’

They heard the climate was better on the opposite coast, so the following day they were back in their hire car, threading across the mountainous interior. It took half the morning to wind around the ravines, up into the cooling mist of the ancient forest, and then to hairpin down into a terraced gorge, lush with date palms and banana trees, where it was a blazing eighty-eight degrees.

They found an apartment in the hippie-run resort at the bottom of the valley. It had a cushion-thin mattress on the bed and a door that took five minutes to unlock, but you could almost see the sea from the balcony and it was only two thousand pesetas a night. Stefano put his foot down about further attempts at sightseeing. For the sake of harmony, Adam decided not to mention the ancient villa which claimed to be the last place where Christopher Columbus had stayed before setting out for the New World; it would do for a rainy day, if it ever rained on this side of the island.

Instead, they went straight to the beach, where the sand was as dark as the volcanic rocks that framed it, and soft as pepper underfoot. The breakers were huge, especially in the shallows, and even Stefano, who tended to be fearless, was daunted by them on the first day. However, he discovered that the trick was to dive into the belly of the wave just before it broke on your head. This sounded terrifying to Adam, but Stefano assured him it was fine when you came out the other side.

‘It’s actually quite funny,’ he said, ‘because you can laugh at the wave knocking everyone else over as it goes higher up the beach, and you’re fine. But you have to be careful there isn’t another massive one coming straight after it.’

Adam was a much less confident swimmer than Stefano, and the sea was too rough for his liking, but he was happy lying in the sun, reading. He grew to recognise the other characters on the beach, who mainly seemed to be Scandinavians and Germans. On the third day he noticed that one of these Scandinavians was wearing his arm in a sling, which had not been there the previous day. It was only then that he noticed there was no lifeguard on this beach, which made him less inclined than ever to do battle with the monster waves. He could not quite understand why everyone else on the beach seemed so keen to go back for more.

He was snoozing at the time of the accident, and it must have been the commotion that woke him. He scanned the crowd of tanned figures clustering around the unfortunate on the sand, looking for Stefano among them. Adam was calm by nature, and not inclined to rush into an unnecessary panic just for the sake of the drama. As he got to his feet, however, there was still no sign of Stefano. He began to realise that, on this occasion, panic might well be justified.

He reached the crowd, pushing through to see who or what was at the centre of the huddle. The sight of a paunchy German crouching over the pale, slender body in stripy trunks confirmed his worst fears.

‘Let me through! It’s my…’ Even here in the throes of terror he worried what word to use. ‘Partner’ sounded so uptight, but ‘boyfriend’ always seemed to invite ridicule when used outside the confines of their own world.

‘Er atmet!’ shouted someone, and then in English: ‘He’s breathing.’

‘Gracias a Dios!’ said someone else.

Amid the relief and jubilation, the German sat up to give Stefano room, and Adam flung himself onto the sand behind him.

‘Stef! What happened? Are you all right?’ he panted.

The green eyes looked up at him groggily through long lashes.

Adam gripped Stefano’s hand, no longer minding what anyone thought, and called up to the little crowd: ‘Has anyone called an ambulance?’

‘I think so,’ said a German accent. ‘Yes, that guy is calling. It’s coming.’

Adam turned back to Stefano.

‘I thought I’d lost you,’ he whispered.

Stefano was trying to say something, and Adam had to lean in close to catch it.

‘I think I saw the eye…’

‘Sorry, Stef, I can’t really understand you. But don’t try to talk now, you’ll have plenty of time to tell me later. I’m so sorry, I didn’t actually see what happened. I think you must have blacked out. But you’re all right now. Lie back, don’t try and talk.’

‘But you don’t understand, it was really weird…’

‘I’m sure it was horrible, but don’t talk now. You’re safe now; try and relax.’

Looking up at the crowd again, he asked: ‘What happened? I didn’t see.’

‘He was knocked down by a wave,’ said the onlooker who had spoken earlier. ‘They can be very dangerous.’

Others offered their own versions of what had happened. They had watched the English boy get knocked over, and they had all laughed, just as he had laughed when it happened to them, but then they could see he was in trouble because the waves were coming fast, one after the other, and whenever he tried to emerge, he was knocked down again.

‘It was hard to help him because the force of the sea was so strong,’ said one of them, apologetically.

From his prone position on the sand, Stefano was still trying to talk.

‘Please, Stef, lie still. Help will come,’ said Adam.

The guy who had administered the kiss of life was still there, a portly, near-naked shape outlined in the white afternoon sun.

‘Thank you so much for helping him,’ said Adam, squinting up at him. ‘Is he going to be OK?’

‘I’m not a doctor. I just know a little first aid. But I imagine yes. Don’t worry.’

‘Thank you,’ said Adam again. It was strange for himself and Stefano to be the focus of concern from so many strangers. He had a sudden impulse to weep, and he fought it back.

After what seemed like an age, but could only have been five minutes, the burst of a siren – that funny, staccato dee-dee-dah chirp that was one of the hallmarks of abroad – announced the arrival of the ambulance.

The concerned but thinning gaggle that still surrounded them parted and two men in black trousers and bright yellow t-shirts – one of them stocky, fortyish, the other younger, taller, ponytailed – pushed their way through.

‘Qué ha pasado?’ said the older of the pair, and one of the Spanish speakers answered. Adam could not complain at being sidelined: he still did not have a clear idea of what had happened, so could not have explained even if he had the language.

The ambulance man crouched next to Stefano and asked him his name.

He replied in a croaky whisper, but someone from the crowd had to step forward and act as interpreter for the rest of the conversation. How did he feel? Could he breathe properly now? How many fingers was the guy holding up? Did he know the name of the island they were on? What day was it?

Now a stethoscope was being applied to Stefano’s naked chest and the ponytailed crewman raised his bare arm to apply the blood pressure cuff. Adam saw a telltale flicker of those green eyes, and was reassured that Stefano was out of trouble: if he was well enough to register a cute first-aider, he was no longer at death’s door.

The older of the men was now standing up and asking Adam something.

‘Sorry, I don’t speak Spanish,’ he said, appealing for support from the onlookers.

‘You are together?’ said a slim Spanish woman of about their own age.

‘Yes,’ Adam nodded, trying not to notice the brown nipples pointing up at him. ‘Si.’

The ambulance man said something else to her and she translated: ‘He want to take your friend to the hospital, just to make sure he is OK, OK?’

‘OK,’ said Adam. ‘Can I go too?’

Stefano was being lifted onto a stretcher now. The ambulance was parked on a track at the top of the beach, where the hot, black sand gave way to rough earth and rougher stones. Adam did his best to keep up, hopping in his bare feet.

‘I’m coming too. Will you wait two minutes while I get our stuff?’

Their towels, cameras, watches, money were all still out there on the beach.

But the guy was shaking his head and saying something in Spanish, as his ponytailed colleague now closed the back doors of the ambulance.

‘But we’re together!’ Adam bristled.

The bare-breasted Spanish woman laid a gentle hand on his arm.

‘He say he cannot take you like this’ – she gestured at his lack of clothing – ‘so you follow behind in a taxi. It’s not far.’

The ambulance was already pulling away, chirping away with short dee-dee-dah bursts to signal that it was on the move again.

The little hospital was at the top of the valley. The road sagged up the middle of the lush oasis in the side of the volcano which had made this side of the island habitable, and then wound back and forth in wide loops as the gradient began to show it meant business. Near the top, a turning pitched off at a tangent and led into what looked like a brand-new neighbourhood, with a gleaming white, flat-roofed hospital at the centre of it.

Adam paid his taxi-driver and hastened inside to track down Stefano.

‘Cartwright,’ he spelled out at reception, writing it down because the silent W was impossible to sound in foreigner-friendly English.

He need not have bothered. Not many tourists had been brought in on stretchers in the past hour, and they knew immediately who he meant.

Adam was directed to a ward on the first floor. He found Stefano in a bay at one end next to a tiny, brown, old man with wires attached to his chest, who was snoring loudly.

Stefano was propped up against a bank of pillows, wearing a pale blue hospital gown. There was an oxygen mask on the bed next to him but he was breathing perfectly well without it.

Adam gave him a discreet peck on the cheek.

‘How are you feeling? What have they said? Have you seen a doctor?’

‘I feel fine now. Did you bring my stuff from the beach? They need to see some kind of ID to keep me here. I don’t see the point, but they say they want me to stay overnight. And I tried to tell them what I saw, but they wouldn’t listen either.’

‘What you saw?’

‘I’ve been trying to tell you…’ Stefano picked up his oxygen mask and took a few long drafts to fortify himself. ‘Something really weird happened. One moment I was in the sea, getting knocked down by the biggest wave you ever saw, struggling to breathe, with water going up my nose, and I remember scraping my face on the sand, so I must have gone upside down. It was really frightening. And the next moment I was all calm. I was looking down on myself on the beach and I could see all those people standing around me, and then you arriving. And I couldn’t hear anything at all, even though I could see people shouting. It was like everyone was on the other side of some…I don’t know…huge glass screen or something.’

‘It must have been horrible. I guess with the trauma, you were dreaming about what was happening. But like I say, don’t dwell on…’

‘It wasn’t a dream, it was real. I was really watching it. And that wasn’t the main thing. After I’d looked down on myself it all disappeared and I was going up this long white tunnel, and it was an amazing feeling, like the best rush you’ve ever had. And I thought I’d never get to the end, but then I did and I saw…’

‘What?’

‘It was an eye.’

‘An eye?’

‘Yes. I’m certain that’s what it was.’

‘A human eye?’

‘Well, I don’t really know. It could have been, but it’s hard to tell when all you can see is an eyeball.’

‘What colour was it?’

‘Sort of bluey-grey. And it was veiny.’

‘Veiny?’

‘Yes, with kind of white vessels flowing across it.’

Adam had always found it tedious to listen to other people’s dreams, which was what this sounded like.

‘I’m sure it has all been really disorientating. But you’re still alive; that’s the main thing,’ he said. ‘You’ve had a lucky escape. Now you just need to get some rest.’

This was one time when he was not prepared to let Stefano get his own way.

In the morning, he was momentarily confused to find himself alone in their double bed. They had rarely spent a night apart in the past five years, and the extra space felt wrong, a luxury he had no wish to enjoy. It was frightening to think how close they had come to disaster the previous day, but he told himself there was no point in dwelling on that. It was all over now, and they just needed to put it behind them and make the most of the rest of their holiday.He planned to have breakfast and then make his way back up to the hospital, but Stefano beat him to it by arriving in a cab before Adam had finished his coffee.

‘They said I could go, but I need lots of rest.’ He pulled out a packet of Marlboro Lights, which had been in the bag of belongings that Adam had left with him at the hospital. ‘Have we got any Diet Coke left?’

‘Go and sit on the balcony, and I’ll bring it to you. Did they also say you could smoke like a beagle?’

‘I’ve had a nasty shock. I can’t not smoke.’

Physically he seemed fine, but he was much more subdued than usual.

Telling himself this mood would pass soon enough, Adam left Stefano listening to music on his headphones while he went to pick up ham, cheese and salad from the supermarket at the bottom of the next block. They had lunch on the balcony, napped, then Adam made them each a gin and tonic. He was not sure if alcohol was allowed, but it seemed important to get back into the holiday spirit.

‘I’ve been thinking about the tunnel, and that eye,’ said Stefano.

Adam’s heart sank.

‘Have you?’

‘Don’t say it like that. Something really big happened to me yesterday.’

‘I know it did. I nearly lost you. You don’t need to tell me. I’m still quite shaken myself, so it must be much worse for you.’

‘I nearly died.’

‘I know you did.’

‘And I went somewhere.’

‘Well…mentally, yes.’

Stefano crunched an ice-cube.

‘I went somewhere,’ he repeated, more forcefully. ‘Nearly, anyway.’

‘Where do you think you nearly went?’ said Adam.

‘You know where.’

Adam genuinely did not know what he was getting at. Then his eyes widened.

‘You mean heaven?’

‘You said it, not me,’ said Stefano, putting another Marlboro Light between his lips and reaching for his lighter.

‘But Stef…’

‘What?’

‘You’re an atheist.’

Stefano shrugged.

‘Aren’t you?’ Adam persisted. ‘You always told me you were. So, you know, you don’t believe in all that stuff. God. The afterlife. Heaven.’

Stefano shrugged again.

‘I’ve always been spiritual.’

‘No you haven’t! You’ve always burned joss-sticks and hung out with people who smoke too much weed. That’s not the same thing.’

Adam was laughing, but Stefano did not join in.

‘I know what I saw,’ he said.

‘You know what you think you saw.’

‘It wasn’t a dream. It was real.’

‘How do you know?’

‘Because I’ve had dreams, and I know what they’re like, and this wasn’t one.’

‘Why? Because it was more vivid?’

‘Yes.’

‘But you were actually on the sand at the time, weren’t you? And before that you were in the sea, being pulled out of it by all the people who rescued you.’

‘That was my body. I left it behind, like you do when you die.’

‘Except you don’t. That’s just a thing people like to believe, because they know they’re going to die, but they can’t imagine not existing.’

‘How do you know? You can be really patronising, you know.’

Adam was not quite certain why he felt so alarmed. They had different interests, which was fine, and he was much more cerebral than Stefano, which was not a problem either. But he had always liked the fact that they had both voted for Tony Blair and they both thought that religion was mumbo-jumbo, without one having to convince the other. Would it be a catastrophe if that altered, and one of them changed his mind? It ought not to be, but the prospect was unsettling nonetheless.

‘OK, I’m sorry,’ he said. There was no sense arguing about it now. They had both, he reminded himself for the umpteenth time, had a shock, and things were bound to settle down.

But he could not resist adding: ‘I can promise you, though, that it’s your brain playing tricks on you, just like it does when you’re asleep.’

‘How can you promise me that? How can you be so sure I didn’t see God?’

Stefano’s eyes were blazing, and Adam forced himself to change the subject.

‘We’ve still got three days’ holiday left,’ he said. ‘Shall we try and find a less dangerous beach tomorrow, and we can just lie in the sun and relax?’

On balance, he decided, it would be unwise to mention Christopher Columbus’ villa.

3

One of the things that distinguished God from some of the more developed creatures of his realm – such as the hominid master-race of the third rock from a middle-sized star in a spiral galaxy in a part of his universe that he technically classified as ‘over there’ – was that he did not have much stuff.

Having spun the whole thing into motion and then sat back and watched, for what those hominids would think of as thirteen billion years, he was not much of a maker. He had neither the tools nor the understanding of how to go about putting things together, never having been shown. Nor did he really have anywhere to put anything, what with objects tending to drift off into the ether whenever he let them go. The possessions he did have were either bits of cosmic jetsam to which he had taken a fancy over the aeons, or remnants of the mysterious, forgotten time before the present universe had got up and spinning, when objects had existed according to very different rules.

Of the latter, his most treasured item was his seeing-tube, a piece of para-dimensional magic that could be directed wherever he chose. Allowing him to zoom in as close as he wanted on whatever grabbed his interest, it was his entry into the scattered, teeming worlds that now spun according to their own magic. He could not imagine living without it, and he always kept it by his side, which was where it was at the moment Stefano Cartwright came so assertively to his attention.

The reason the creator treasured his seeing-tube so much was that he was not blessed with long-distance vision. He was excellent up close, which was not surprising, given how near everything in his universe had been back in the early days. As time had gone on, however, he had struggled to adapt to the ever-growing immensity of his realm. Big-picture views were fine, but if he wanted to see what was going on in any particular spot, he had to shift himself closer, which could be irritating if there was nothing much going on there after all. As the distances became ever greater, he could also never quite shake the fear that he might lose his way in some backwater galaxy and not be able to find his way back to the centre. His tube got around all those problems, allowing him to zoom in wherever he wanted without actually moving.

By contrast, his hearing was magnificent, as if he had been designed all along to exist in an infinitely expanding territory. He could pick up sounds from one end of his cosmos to the other, even if he sometimes had no idea what was making them. The problem with this hyper-sensitivity was that major and minor sounds threw themselves on his attention with equal weight. Stellar conflagrations made a primordial din, as loud as anything in the universe, but even if he was engrossed in watching a supernova – he never tired of the ever-changing colours – he could still be distracted by a much lesser commotion, something tiny and parochial that managed to penetrate through. It did not always happen: it was more of a random occurrence that the creator would have struggled to explain, if he had ever given it much thought. Since he had no real need to know how or why anything worked, he never had.

One of these random penetrations had now attracted his attention. The disturbance took the form of a crash and cry, unmistakably hominid, even to a deity with only sporadic experience of these creatures, but somehow primitive. It did not articulate anything beyond raw feeling: first pain, then anguish, and finally terror. It was also muted, as if it were being dampened by some great vastness, denser and more destructive than the enveloping nothing of space. Alongside it was a rushing sound, as of liquid, and a gurgling or bubbling, as if something gaseous were being forced through it. Then there was silence.

The creator turned away from his supernova – it would be there for a good while yet – and reached for his tube, which could be extended in whatever direction he chose to point it. Now he thrust it through the galaxies towards its target and peered through the nearest end. Light coursed down the dark cylinder as he did so, creating a massive torch arcing down to the surface of the rock. He was able to fix with remarkable accuracy – only two or three misses before he got it right – on the precise spot where the commotion had started. At first it was all a blur, and he had to twist the little wheel at top of the looking-end, which had been made slightly too small for divine comfort. When, after a little fumbling, he got it to work, he saw that he was not alone. Looking back at him were two large, green eyes, framed by long lashes, blinking in the glare.

As the light filled the length of the tube, the eyes seemed to accustom themselves to the brightness; they widened, first in astonishment and then fear, whereupon they vanished as quickly as they had come. Then the tube went dark and it was God’s turn to blink.

The creator had been following the fortunes of this planet long before its hominid inhabitants had been around to call it Earth. He remembered the place when it was dominated by lizards, and he had watched those scaly machines shake the rock with their tread and beat the gassy surround with their wings. As they wrangled and sparred, he wondered which of them would win the battle for ascendancy.

In the event, none of them did. After a long observation tour taking in several million galaxies in a distant part of the universe, God had returned to find the planet barely recognisable. He had thought he had got the wrong place at first, and it was only after careful checking around the galactic neighbourhood that he could be certain this was the correct spot. Pushing his tube through a ring of dust and watching as the white light coursed down it, he saw that the lush, sprouting vegetation was smoking and charred. Nothing shook the ground or beat the grimy gas any longer. The creatures that had once done so now lay in an advanced state of decomposition, little more than stick frames to suggest their former shapes. As the planet turned on its axis, the creator traced his tube up and down its surface scouring for clues to what had caused this destruction. One third of the way round, he found what he took to be the culprit. Embedded in the planet’s central belt was a piece of rock. It was a mere pebble by the standards of the cosmos, but it had clearly packed enough mineral punch to smash a smouldering crater into the surface of the Earth. Everything was much blacker here, at the centre of what had evidently been a fiery maelstrom. The stick frames that dotted what remained of this landscape were as black here as everything else, and the creatures must have been consumed by the inferno. Elsewhere on the rock they seemed simply to have expired.

The creator allowed the planet to spin for rotation after rotation as he surveyed the devastation. He wondered if he might have done something to prevent all this. He could perhaps have deflected the boulder, if only he had known it was coming. But he could not be expected to follow the trajectory of every flying pebble. Besides, how was he to know its impact would cause such destruction? Since the physical operation of his universe was a mystery to God, he had always judged it best not to meddle in what he understood so imperfectly. It was a shame about the destruction of the reptiles and pretty much everything else on this bushy little planet, but it was not really his responsibility, and he could not be blamed.

As it happened, the rock was not completely dead. He got into the habit of checking now and then, just to see if anything was sprouting. And sure enough, it was, and then some. New creatures rose from the ashes, dominated eventually by a race of apes. At first they seemed pretty basic creatures, tiny in comparison with their predecessors. Gradually, however, they rose onto their lower limbs, organising their shouts and moans into a form of communication that set them apart from the many other species that had also emerged from the devastation. This ability to talk, as they called it, did not make them unique in cosmic terms, but it was rare enough to raise Earth a good deal higher on God’s list of rocks worth keeping tabs on. He might even go so far as to say he had an affection for the place.

He shook his suddenly darkened seeing-tube. It played up occasionally, which was not surprising considering how long he had had it, and he had been meaning to take a look at it when it was retracted. Now, however, it blinked back to life, which was a relief, allowing him to concentrate on the more pressing issue of finding what that disturbance had been.

The green eyes with the long lashes had definitely vanished. Instead, as he fiddled with the focusing rotor, the creator found himself looking at a strip of dark, grainy sediment where the dry part of the planet met the liquid part. On this strip were a number of scattered hominids who were instantly notable for having removed the garments with which these creatures normally covered themselves. God had noticed this ritual before: it involved prostrating themselves before their star. Sure enough, the strip of sediment was dotted with the bright woven mats traditionally used for this worship, although not all the hominids were prostrated. At the far end, a group of them – some completely ungarmented, others with a protective cloth at the top of their lower limbs – propelled a small, round object back and forth over a line suspended between two poles. At the near end, framed by the circle of his tube, was a different kind of gathering. Several of the creatures were gathered around a pale hominid shape stretched on the black sediment. One of this crowd, a furry male with a pendulous hide, was bending over it.One of the onlookers shouted something in an Earth tongue and the furry hominid pulled back, giving the creator a clearer view of the prostrate figure. It made a rasping noise and opened its eyes, and he could see that they were the green ones he had seen down the tube.

The onlookers emitted a collective, high-pitched roar that made God wince. If only he could turn down his internal volume as easily as he could adjust the focus of his tube.

Now a self-propelling craft on rotors had drawn up at the edge of the strip, announcing itself with a searing wail that nearly made the creator drop his end of the tube. Two more hominids emerged from this craft, standing out from the rest of the creatures because they were fully garmented. The group around the prone creature parted to let them through. They lifted him onto a woven mat between two sticks and proceeded to bear it back to their craft. The craft gave another short wail – God was ready for it this time – and then it was back on the move. It performed a rapid manoeuvre to point itself in the opposite direction and then set off towards a collection of straight-edged hominid structures. Rather than stopping there, it turned towards the centre of what the creator could now see, as he panned backwards, was a free-standing rocklet. The craft joined a smooth, grey track that wound in broad, slow loops up the angled surface of the rocklet until it reached a larger collection of hominid boxes higher up. Here it wailed some more, making other craft shy from its path, and eventually stopped in front of the largest structure in the cluster. The two garmented hominids got down and opened the flaps to retrieve the stricken creature on his mat. Transferring him onto a raised pallet on rotors, they pushed him through a wide portal at the entrance of the structure and disappeared.

The creator continued to peer down the tube, irritated that he could not follow. Magical as his device was, it would not see through solid structures. This was frustrating, because his interest was well and truly roused. Homo sapiens had been shouting in anguish for tens of thousands of years, and if one of them managed to shout loud enough to attract the creator’s attention over the general clamour of the rest of the universe, he was bound to be curious.

Something else bothered him too. As he looked straight into this hominid’s eye, it had felt as if that eye was looking straight back at him. In all those aeons of existence, that had never happened. He had never been spotted before, and he was not at all sure he liked the idea of being spotted now.

4

If anyone had asked Stefano before his mishap with the wave if he believed in God, he would have said without hesitation that he did not. He had described himself as an atheist for all his adult life and more, having decided at the age of fourteen that religion was make-believe, and had given it very little thought since then.

Until that point, his attitude had been very different.

His mother, while not a church-goer by inclination, had convinced herself when Stefano was small that regular attendance at their local Anglican church would help him gain entry to the better of the two available primary schools, which was run by the Church of England. So he had been taken there on at least a couple of Sundays each month from the age of four. He liked the place, because the vicar made everyone laugh with a stand-up routine that involved pretending to treat squalling babies as if they were hecklers, and sending the congregation home at the end of every service with strict instructions on what kind of roast they should eat for lunch. It made everyone hungry, as well as making them laugh, thereby giving the service not one but two positive associations in their minds for the rest of the week.

He was duly admitted to the C of E school, where the vicar paid occasional visits, cracking more jokes to the class and making those children whom he knew by name, including Stefano, swell with pride. There were also daily prayers, where Stefano sang the hymns lustily and squeezed his eyes tight shut as he chanted Our Father, who art in heaven, Hallo be thy name, equally proud that he knew the words so well. It would never have occurred to him to peep.

He liked the stories they did in class, because the pictures took him to an exotic, far-away world full of nice animals like camels and donkeys, where everyone wore bright colours, including the men – unlike the grey jackets that men in the real world seemed to wear – and the weather was always hot and sunny. Aside from those obvious exceptions like the Flood and the Parting of the Red Sea, the stories were set in a world that always looked sun-kissed and sandy, like the slides of Spain that his Auntie Jill and Uncle Richard sometimes showed when they came to visit. It was refreshingly different from the rain-spattered, suburban sprawl visible through the window of their prefab classroom.

He also liked watching big biblical epics on television. His mother had a great fondness for Charlton Heston, who wore a short tunic and had thick, bronzed legs. Slightly disloyally, Stefano found that he preferred Yul Brynner: he was so handsome with his splendid pharaonic necklace nestling on his bare, hairless chest, and even though he played Moses’ wicked royal brother, he prompted a wistful, breathless craving deep in Stefano’s chest that he did not properly understand. He also knew that the poor Hebrew slaves, sweating and straining as they hauled great blocks of stone around, were being treated terribly, but he liked watching them, because they, like Yul Brynner, were stripped to the waist.

At his secondary school, which was for boys only, there were more daily prayers and school services at the end of every term. The singing of the hymns became more dismal, because no adolescent youth in his right mind could look as if he were enjoying them, and while Stefano took a certain pleasure in being different, he was not that perverse. Even for him, those assemblies were an ordeal: the headmaster droning on with his interminable thees and thous, as rows of fidgety boys shot peashooter pellets at one another. Unlike his classmates, however, Stefano did not loathe their twice weekly scripture lessons. These were taught by a lithe, hyperactive teacher of indeterminate age called Mr Thompson, who had never done any harm to anyone but had been nicknamed Tommy Tosspot by a previous, long-departed generation of boys, and had been known as such ever since. Stefano took a lively interest in Bible study and, because he had been paying more attention to this topic than to any other over a period of years, he got good marks, far better than in any other subject. He seemed so interested that, at one point, Tommy discreetly asked if he thought he might have a calling.

Life, however, was calling him in another direction. The stirrings occasioned by Yul Brynner and the Hebrew slaves had now made themselves more physically manifest as he grew into teenage maturity. The discovery that he was aroused by male beefcake, and not the big-busted nymphettes in the battered magazines that were passed around the class for nightly loan, did not alarm him. The pleasure he had already begun to take in being different had perhaps been an early intimation of this much more major departure from the norm, and it meant that he was happy to take the discovery in his stride, with a clear sense of the benefits of the situation. He and a boy in the year above him, Martin Morris, had been sucking each other off since Stefano was thirteen, taking them to a level that even the most confident members of his class could scarcely dream of in their courtship of girls from the school half a mile away.

His only concern was religious. He had never heard the act that he carried out with Martin Morris explicitly censured, not by the vicar, nor Tommy, nor anyone else. Stefano was not entirely naïve, and he knew that this was not because it would be smiled on, but rather that it was considered too shocking even to name. This puzzled him. He had always grasped the good sense of most Christian morality: if you accepted that you should do unto others as you would have them do unto you, it was obvious why it was wrong to kill, steal or lie. It was much less clear why it was sinful for Stefano to act on physical urges that he could no more control than he could change the length of his toes, and which were not doing anyone else the slightest harm. Yet he had an ominous feeling that there was meant to be a special place in hell for people who did this kind of thing.

His worry gave scripture lessons a more sombre twist, but he continued to engage in debate with Tommy, raising his hand and taking a more willing part in discussion topics than the rest of the class put together. It was one of these discussions, in the December when he turned fourteen, that would prompt a wholesale reassessment of his religious worldview.

They were talking about the visit to the Holy Family of the Three Wise Men, with their gifts of gold, frankincense and myrrh.

Tommy wanted to talk about frankincense and myrrh. What were these things, and why were they valued? He brought out the lump of frankincense resin that he had acquired on one of his Holy Land pilgrimages, and passed around a little vial of myrrh oil.

‘Smells like liquorice, sir,’ said a boy called Morgan, who was good-looking and charismatic, with the effect that everything he said was confident and entertaining. If he was paying attention, the rest of the class did too. ‘D’you think the baby Jesus liked liquorice?’

Drew, who always sprawled in the back row, reached forward and dabbed some drops of this essence behind the ears of Peters, whose glasses were held together with Elastoplast and was often bullied.

There was a muffled commotion as Peters tried to push him away and wipe the liquorice perfume off without drawing Tommy’s attention.

‘Why would anyone want it, though, sir?’ persisted Morgan.

‘It was highly prized,’ said Tommy. ‘It was used in medicine and in incense, so it was a very generous gift – befitting the baby who they had been told was the king of the Jews. The same goes for frankincense.’

For Stefano, the interesting gift was the third one.

‘Sir, sir,’ he said, waving his hand. ‘What happened to the gold, sir?’

Tommy brightened, as he always did when Stefano asked a question. This time, however, there was bemusement in his face too.

‘What do you mean, what happened to it? I’m not with you.’