8,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Lightning Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

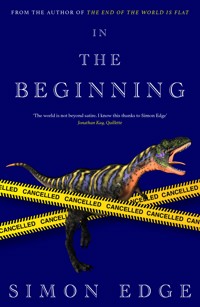

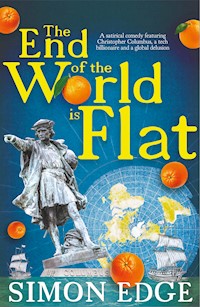

'I laughed so hard I nearly fell in my cauldron. A masterpiece' JULIE BINDEL 'A bracingly sharp satire on the sleep of reason and the tyranny of twaddle' FRANCIS WHEEN Mel Winterbourne's modest map-making charity, the Orange Peel Foundation, has achieved all its aims and she's ready to shut it down. But glamorous tech billionaire Joey Talavera has other ideas. He hijacks the foundation for his own purpose: to convince the world that the earth is flat. Using the dark arts of social media at his new master's behest, Mel's ruthless young successor, Shane Foxley, turns science on its head. He persuades gullible online zealots that old-style 'globularism' is hateful. Teachers and airline pilots face ruin if they reject the new 'True Earth' orthodoxy. Can Mel and her fellow heretics – vilified as 'True-Earth Rejecting Globularists' (Tergs) – thwart Orange Peel before insanity takes over? Might the solution to the problem lie in the 15th century? Using his trademark mix of history and satire to poke fun at modern foibles, Simon Edge is at his razor-sharp best in a caper that may be more relevant than you think.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

Praise for The End of the World is Flat

‘In between punching the air and shouting “yes!”, I laughed so hard I nearly fell in my cauldron. A masterpiece’

Julie Bindel

‘Without mercy, this merry romp punctures the idiocy that would turn language and good sense upside down and try to divide us all into either true believers or bigots. It’s a frightening reminder of what happens when we reject the power of dialogue’

Simon Fanshawe

‘A highly-entertaining satire about ideology, social media manipulation, and lobbying fiefdoms that have overstayed their welcome. This is Animal Farm for the era of gender lunacy, with jokes – and, right now, we all need a laugh’

Jane Harris

‘This book is very, very funny. It’s also way too convincing as a horror story – Simon Edge writes a completely believable account of how this kind of ideology could seep into great institutions. And possibly, in another form, did’

Gillian Philip

‘A satire that skewers the insanity of gender-identity ideology with the wit and brilliance of a modern-day Swift’

Helen Joyce

Simon Edge read philosophy at Cambridge and was editor of the revered London paper Capital Gay before becoming a gossip columnist on the Evening Standard and then, for many years, a feature writer on the Daily Express. He is the author of four previous novels. He was married to Ezio Alessandroni, who died of cancer in 2017. He lives in Suffolk.

Published in 2021

by Lightning Books Ltd

Imprint of Eye Books Ltd

29A Barrow Street

Much Wenlock

Shropshire

TF13 6EN

www.lightning-books.com

Copyright © Simon Edge 2021

Cover by Ifan Bates

Typeset in Bembo, 18th Century and Helvetica Neue

The moral right of the author has been asserted. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

The orange-peel map projection image by Tobias Jung on page 19 is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 international licence.

Google is the trademark of Google LLC

Twitter is the trademark of Twitter, Inc

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Printed by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY

ISBN: 9781785632402

A time is coming when men will go mad, and when they see someone who is not mad, they will attack him, saying, ‘You are mad; you are not like us’St Anthony the Great

For Allison, Gillian, Julie, Marion, Maya and Rachel. Heretical globularists all

Contents

PART ONE

PART TWO

PART THREE

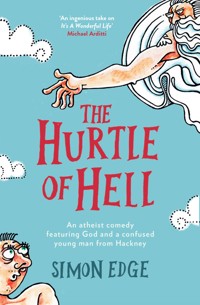

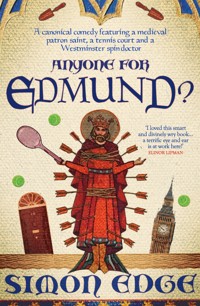

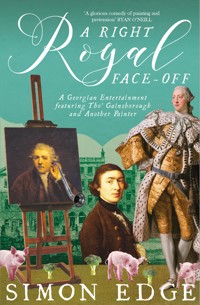

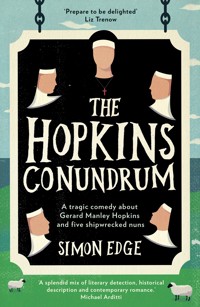

By the same author

PART ONE

The admiral knelt before the crucifix that he’d attached to the bulkhead of his cabin and began to pray.

‘Lord God Almighty, send me a fair wind, I beseech you, that our little fleet may voyage safely across the Ocean Sea and claim the bounty of the Indies for your glory, and for that of your noble servants, their Catholic majesties. Put courage in the hearts of the men of our three ships, for I know they lack it. Watch over us as we plot a course that no man has ever sailed.’

And help me prove wrong that sneering, self-regarding sack of hot air they call the Bishop of Avila, he wanted to add, but his eminence no doubt also had the ear of the Lord. If the admiral asked God to choose between them, he was in danger of emerging the loser. Better not to mention the bishop. Success would speak for itself when the time came.

Despite his success in persuading the Queen of Spain to back his voyage, his own humiliation before the learned council, five years earlier, still rankled.

As the promoter of an adventurous scheme that turned so much popular wisdom on its head, he had long grown used to ridicule. He expected urchins to tap their temples as he passed them in the street, mocking him: the famous madman who believed the earth was round. But he had hoped for better from the professors and the elders of the Church who gathered at the Dominican convent in Salamanca to hear his case and report back to their majesties.

Their attitude to him was downright childish. He could see them frowning and nudging each other – ‘what did he say?’ – in a pantomime display of not understanding his Spanish. His Genoese accent was strong, he knew that, and his grammar admittedly chaotic, but he had spent his adult life making himself understood to Spaniards, from the lowest cabin boy to Queen Isabella herself. If they could understand him, so could these greybeard professors and shaven-headed monks. They did it for effect, to knock his confidence. They followed his Spanish only too well when he started challenging their beloved superstitions. At that point, they brought out their whole arsenal of arguments.

‘Are you seriously asking us to believe there’s a part of the world where everything is inverted?’ scoffed a professor of mathematics from Cordoba. ‘Where the trees grow downwards and the rain falls up?’

In vain did he try to explain Aristotle’s concept of gravity, that an object would always fall to the earth. These wise men did not want to hear such things from a rough, ignorant sailor.

More objections followed. ‘Even if you could sail down over the horizon to India, surely the gradient would be too steep for you to sail back up again?’ That was a friar, one of their hosts.

‘These countries on the bottom of the world – where are they mentioned in the Bible?’ croaked the elderly Archdeacon of Leon, his finger trembling as he pointed it accusingly at their petitioner. ‘If they’re inhabited by men, those men cannot be descended from Adam. And that, sir, is heresy!’

All the while, the man of the sea attempted to maintain his dignity, but it was difficult, particularly as he watched the face of the bishop, the arbiter of the council, who would relay its verdict to their majesties. Avila made no secret of his scorn, hear-hearing louder, nodding more vigorously than anyone. At the mention of heresy, his eyes shone with the light of the Inquisition.

Years of delay ensued. The navigator was forced to trail around Spain after their majesties, watching the bishop, his nemesis, drip ignorant warnings into the queen’s ear: the scheme was vain and impossible; her majesty should do what the King of Portugal had done and send the Genoese rogue packing; it would degrade the dignity of the crown to lavish honours on a stranger with no name or reputation.

No name? Cristobal Colón was a decent enough moniker. It wasn’t quite the one he was born with, but he had made it more Spanish so that it tripped more easily off their majesties’ tongues. And now, at last, he had a splendid title to go with it. Grand Admiral of the Ocean Sea, no less, even before they had cast off or sailed a single league across that water. Because, in the end, the queen had ignored the Bishop of Avila and his council, and said yes to Colón. She had given him three ships and her blessing. The western route to the Indies was his to secure, to justify her faith in him.

Light was beginning to enter his cabin through the thick panes of glass at the stern. It was time to give the order. The admiral made the sign of the cross, heaved himself to his feet – after so many years of waiting, he was an old man of forty-two, with stiff knees to prove it – and strode out onto the deck. The captain of the Santa Maria awaited his nod, which the signal officer would relay to the captains of the Pinta and the Niña.

Let the adventure commence.

1

From her doorway, Mel Winterbourne watched Shane, her deputy, with interest. He was waiting impatiently next to the printer, shifting from one foot to the other and grabbing each page as soon as it appeared, virtually pulling the paper from the rollers, rather than letting it drop into the output tray. Mel had worked in an office environment long enough to spot a colleague printing documents on the sly.

She’d been trying to wean herself off teasing him, but he presented too easy a target. She set off for a casual walk around the office. Focused on his task, he didn’t notice her sidle up behind him. A few inches from his ear, she said softly: ‘Printing out your CV, Shane?’

His entire body jerked with shock as he spun to face her, the blood rushing to his cheeks. He was half a head shorter than Mel, stocky, with cropped hair and a full Victorian beard.

‘No,’ he said. He grabbed the papers he’d printed so far and clutched them to his barrel chest. ‘It’s just…erm…a report.’

‘Honestly, it doesn’t bother me either way,’ she said. ‘There’s no law against applying for jobs.’

‘But I’m not app—’

She turned away, brushing off his denial, so he couldn’t see how much amusement her ambush had given her. She wished she could see him squirm, but she’d have to make to do with the mental picture.

Mel meant what she said: she wouldn’t have the slightest objection if he looked for another job. No reflection on his abilities: Shane Foxley was the perfect deputy – competent but unthreatening. Rather, the simple truth was that, if he found another job, she’d feel less guilty about her plan to shut the whole place down.

The same went for the whole team, presently hunched over mobiles or tapping quietly at keyboards. When she was their age, office life was all personal phone calls and yacking; this generation was so much more earnest and diligent. She really did wish them well, and it pained her to have to let them all go.

They would hate her for it, of course, but she’d never cared about popularity, and in the end they’d all be fine. In its twenty-year life, the Orange Peel Foundation had set a benchmark for effective single-issue campaigning, and other employers would fight over its staff. They would all get a decent severance package, too. That was the least Mel could do for them.

There were three dozen of them now, what with the part-timers and the job-sharers. It was a far cry from the one-woman operation she’d set up in her thirties, as a sideline from her day-job as a journalist.

At the time, she’d been deputy travel editor of the Sunday Standard. It would have been a wonderful gig, if only her boss hadn’t grabbed all the plum trips for himself, leaving Mel to run the desk during his frequent absences. She spent all her time chasing copy, writing headlines and proof-reading spreads, while he swanked around the world’s flashiest hotels. In the normal run, she’d have expected to inherit his job eventually, but he told anyone who’d listen that he wasn’t going anywhere.

Then she had her big idea.

She got it from an item in the news pages of her own paper. Two English backpackers had gone missing during a trek across Australia and were initially feared dead. The drama dominated the UK front pages for the best part of a week, as an anxious nation feared the worst. Then the couple turned up safe and well. Asked at a press conference how they’d got so badly lost, the male of the pair explained that Australia was much bigger than it looked in an atlas. The duo promptly became a global laughing stock. Australia’s Prime Minister was widely reported as saying: ‘Couldn’t the stupid Poms have looked at a bloody map?’

Without wishing to be a kill-joy, Mel could see their point. The ridiculed Brits had made a previous trip across Alaska, which looked as big as Australia on the traditional map of the world, but in reality was only a fifth of the size. They had indeed looked at a bloody map. That was the problem.

At the press conference, nobody mentioned the sixteenth-century Flemish cartographer Gerardus Mercator, but Mel knew enough about the history of map-making to identify his role in the story. The travellers’ confusion derived from Mercator’s solution to the age-old problem of how to represent a spherical earth on a flat sheet of paper. He chose to treat the planet as if it were a cylinder, not a globe, so that lines of longitude which actually intersected at the poles became parallel. Displayed on every schoolroom wall, the Mercator projection made Greenland the size of South America, when it was really no bigger than Mexico. If the stupid Poms had tried to walk from Baffin Bay to the Greenland Sea, they might have been pleasantly surprised.

The projection’s greatest absurdity was to make Antarctica look bigger than all the other continents put together. To divert attention from this unfortunate distortion, maps were often printed with most of Antarctica chopped off, so that the equator came two-thirds of the way down the page, rather than bisecting the map at its mid-point. That reinforced the sense, already entrenched in global power relations, that the northern hemisphere was more important than the south.

This much Mel had known already, but she began to read further into the subject, looking at why an alternative had never emerged.

Mercator’s map had endured for nearly five centuries, she learned, because sailors liked it: the projection distorted areas and distances, but navigators could rely on it to send them in the right direction. That was what mattered most when you were trying not to get shipwrecked.

Nevertheless, many other cartographers had proposed solutions of their own. Mel learned to distinguish ‘conic’, ‘cylindrical’ and ‘azimuthal’ approaches, and to tell the difference between ‘interrupted’ and ‘uninterrupted’ projections. She came to understand that each rival map always had its own merit – representing shape, direction, distance or size accurately – but none could ever get all those elements right. It wasn’t that nobody had managed it yet; it was a mathematical impossibility, because there was no way the surface of a sphere would be rendered accurately in two dimensions.

But one approach, to Mel’s eyes, came pretty close.

In an ‘interrupted’ projection, the surface of the globe was effectively unwrapped and laid out flat. The result was an accurate representation of the surface area and shape of the planet, but it didn’t fit neatly into a rectangle, so it looked peculiar at first sight. The best-known example of this approach was nicknamed the ‘orange-peel’ projection, because it resembled the skin of an orange, carefully removed in one piece and then flattened out.

It was next to useless for sailors, because the interruptions in the map – the voids in the orange peel – were deliberately arranged to cut through oceans rather than land masses. For anyone else, it presented every country accurately and had the further merit of never letting the viewer forget the earth was a sphere, not a rectangle.

With the story of the lost Poms still in the news, Mel went to see her editor. She told him she wanted to tell the history of map projection from Ptolemy, the Greek mathematician who first described the problem in detail, to Mercator and beyond, with examples of why these abstruse cartographical arguments mattered.

The editor, a forty-a-day man who lived in dread of each week’s sales figures, laughed in her face. ‘I’ve been in this business a long time,’ he wheezed, ‘and I can tell you this: the word carto-sodding-graphical doesn’t sell papers.’

Mel could see his point, and she kicked herself for messing up her pitch, but she refused to back down. ‘Trust me, it doesn’t need to be dull,’ she insisted. ‘Will you let me write it anyway? I’ll do it on spec, entirely in my own time. Just give me a chance to show you how interesting I can make it.’

Armed with his grudging go-ahead, she pulled out all the stops to construct the feature. She persuaded Sir Beowulf Fitch, the aristocratic, chilblained polar explorer who happened to be an old family friend, to give her a quote. That, in turn, helped coax a contribution from Teddy Skillett, the heart-throb adventurer then hacking through the Amazon rainforest on BBC2. Both told her Mercator was more trouble than he was worth and should have been binned a couple of centuries ago.

She struck further gold when she secured a response from Cora Odell, the telegenic professor of geography famous for delivering a racy series of Reith lectures. ‘Everyone agrees that Mercator needs updating,’ Odell said, ‘but squabbling map-makers haven’t been able to unite around a suitable replacement.’

Finally, Mel quoted a primary-school headteacher from Hampshire – it was actually Rachel, one of her closest friends from university – who said people would always picture the world as they’d been taught to see it as kids, which was why it mattered to show it accurately from the outset. She added that she’d love the opportunity to teach a class about an orange-peel map: it conveyed a tricky concept in a fun way that children would love.

The celebrity names won Mel’s editor over, but her diligent approach seemed to impress him too. For their part, the newspaper’s designers made a good job of the layout, using vintage maps, seafaring portraits and a nice shot of an orange being peeled to create an appetising spread.

The subsequent postbag demonstrated that the subject had struck a chord. The Standard liked to put its name to crusades on a range of issues, from the legalisation of cannabis to courtesy titles for the same-sex partners of peers, and alongside them it unveiled the Orange Peel Campaign. Fitch and Skillett had already endorsed the call for the orange-peel projection to be taught in primary schools. The eponymous hosts of the kids’ TV show Zak ’n’ Jack on da Box now joined them, along with Dame Daphne Aduba, the iconic former presenter of Play School.

With Rachel’s help, Mel prepared a lesson plan to introduce the orange-peel concept to youngsters. After a lot of fiddly work with a pair of sewing scissors, she managed to cut out a single piece of orange-coloured felt that could be wrapped around a globe, with no gaps or overlaps, and then spread on a flat surface. Rachel loved it, as did her colleagues who tested it in the classrooms. They all said Mel ought to get the continents printed on the felt and sell these shapes as an educational resource.

This took time and energy, but Mel discovered she enjoyed it far more than commissioning travel articles. A friend of her father’s encouraged her to set up a charity, showing her how to apply for start-up funding. The procedure was daunting at first, but the advice and guidance were good, and within a year she was able to cast off from the Standard and pay herself a small salary as director and sole employee of the Orange Peel Foundation.

She worked twelve-hour days, but the rewards were great, as she persuaded first primary schools and then whole education authorities of the merits of her case. Rachel was right: demand for the orange-peel maps was strong. The resulting income meant Mel was able to employ staff: just one part-time assistant at first, who then became full-time, followed by a second colleague, and so on.

As the foundation grew, secondary schools asked for their own resource packs. Mel was in constant demand as a speaker, patiently explaining her own solution to the Mercator problem to everyone from WI groups to committees of MPs. She and her staff talked regularly to the media while also lobbying the publishers of maps and atlases. They engaged in international outreach too, re-peeling the orange to centre whichever country they planned to target.

As the charity matured, it developed a kitemark scheme called the Zest Badge, which proved to be an idea of genius. Every business and public body that wanted to show off its progressive, modern credentials could do so by demonstrating, for a small fee, that it was Orange Peel-compliant. It cost those participants peanuts relative to their turnover, but for the charity itself, the fees amounted to a handsome income.

Mel’s proudest moment came, after fifteen years, when she went to Buckingham Palace to receive the MBE. As her guests, she took her parents, who treasured the video of the occasion. She was one of the few recipients of the honour ever to be invested by Prince Philip, and her own treasured memory was the Duke saying to her, with the merest flicker of a wink: ‘I hear we gave you this for drawing maps on oranges.’

Much more recently, she had been summoned to meet a different kind of royalty: the leadership of Google in Silicon Valley, whom she’d spent years lobbying for a more modern approach to the digital maps on billions of mobile phones.

She appreciated that Google maps were meant for scrolling, in which context the odd-shaped voids in the orange peel would make no sense. Nonetheless, it was absurd that the world’s most influential corporation continued to respect Mercator’s distorted country sizes. The idea was to persuade them to consider using some other, more accurate projection.

At the suggestion of Xandra Cloudesley, her board chair, she invited Shane to go with her. ‘No offence,’ Xandra had said, ‘but he’s closer to their generation. You never know when a millennial might come in handy.’

Mel wasn’t happy to be lumbered with Shane, but she was glad of the moral support, as well as one significant piece of input. On their way into the Googleplex, they passed a life-sized effigy of a T-Rex skeleton, which Shane had read was meant to be a reminder to all the company’s staff of what happened to dinosaurs.

‘Tell them Mercator is the T-Rex in this story,’ he suggested.

It was a good idea, and she worked the line into her presentation. It seemed to work. The t-shirted executives responded appreciatively to her address. Some of them had already done enough homework to acknowledge that a problem existed. The meeting ended with a commitment on Google’s part to commission a study into an alternative way of presenting their maps.

As they emerged from the building, Mel and Shane gaped at each other in gleeful disbelief. Mel even allowed herself to be high-fived.

There was a downside, though. She knew, as they flew back across the Atlantic, that this was the beginning of the end. Once the Google study was under way, there would be little left for Orange Peel to do. She’d long believed it would be better to go out riding high on success, like the charity equivalent of Fawlty Towers, than to carry on for the sake of it, inventing new problems just to keep everyone employed. That would be fundamentally dishonest.

Even if it meant abolishing her own job, the most satisfying and authentic thing any campaigner could ever say was surely, ‘My work here is done.’

That was the subject of her meeting with the trustees this afternoon.

The original big names – the Fitches, Skilletts and Adubas – were long gone, making way for a less starry but harder-headed board: City types who knew the ways of the world and were prepared to offer their professional expertise and wisdom in return for philanthropic cachet. At their helm was Xandra, founder and CEO of Hippo PR (because hippos were always depicted as smiley, lovable creatures, even though they were the most dangerous animals on earth). She exuded loud, camp fun but left no doubt that crossing her would be insanity. Mel had observed that tacit rule and had always found Xandra to be a supportive chair.

Mel’s phone rang. It was the main reception desk downstairs, letting her know Ms Cloudesley was on her way up to the boardroom.

‘Thanks,’ she said, picking up the single hard copy of her report on the dissolution of Orange Peel, which she’d printed out at home for confidentiality. That was a tip Shane ought to learn.

The boardroom was on the top floor of the building they shared with two smaller NGOs, an environmental consultancy, a graphic design studio and a teeth-whitening clinic, whose staff flashed dead-eyed smiles that smacked more of salesmanship than affability.

To her surprise, Shane stood waiting at the elevator doors, a brown A4 envelope in his hand. He was still looking shifty, trying to avoid her eye. It was her own fault: she must make more effort not to goad him. She assumed he was going out to post his secret letter and was surprised when he joined her going up.

‘What floor?’ she said, her hand hovering over the buttons.

‘Same as you. Xandra asked me to come,’ he added, seeing her raise her eyebrows. He looked at his watch, then started brushing lint off his lapel.

‘Did she?’ Mel shrugged as if it were no skin off her nose, but she was irritated. If Shane was in the room, how was she meant to make her confidential presentation on winding up the foundation? That was the main item on the agenda. What the hell was Xandra thinking?

The lift pinged as they reached the top floor. Maybe Mel could have a quiet word before the meeting started.

But Xandra was already in place at the head of the boardroom table. She inclined a cheek to be air-kissed. Her cheeks were her most striking feature. Her first face-lift had been subtle, taking years off her without looking obviously artificial, but the slope since then had been slippery: she’d had her nose narrowed, her lips widened and her cheeks filled, and the latest procedure had left her skin shinily taut over two improbable apple-mounds. Even though Mel knew to expect them, they shocked her every time she saw them. On these occasions, she always had a flash of worry that she’d say ‘face’ or ‘nose’ at some inappropriate moment, because those were the words in her head. Please let her not do it today, in front of Shane.

Three other people sat at the table. Damon Burch, on Xandra’s left, was a merchant banker in his late thirties who took his board duties seriously, in what Mel assumed was a bid to keep himself human; if so, it was working. Next to him was Geena Holland, an old friend of Xandra’s and a partner at one of the big accountancy firms. Geena had never given up smoking; she had a throaty cackle but was also a tough operator. Opposite Xandra at the bottom of the table was Cyrus Benjamin, a tech entrepreneur of around Damon’s age who claimed to have become a millionaire at the age of twelve after launching a start-up in his bedroom. Mel had never entirely believed this, and the story had been entertainingly debunked in a recent best-selling account of the dot-com boom, but Cyrus had his uses. He’d played a valuable role in setting up their meeting in California. The only missing board member was Miranda Zappel, a corporate lawyer who had a habit of sending apologies.

‘Miranda won’t be joining us today, which means we’re all here,’ said Xandra, when Mel and Shane had taken their seats. ‘I hope you don’t mind my asking Shane to join us, Mel?’

She knew Xandra didn’t care if she minded or not, but there was no point in showing her annoyance. ‘Of course not. Why would I? Although Shane won’t have seen the report I’ve sent you all, in which I set out my proposals going forward.’

‘Going backward, I’d have said,’ said Xandra. She glanced theatrically around the table, and Geena obliged with a smoky chuckle. ‘It’s hardly a vision for the future, is it?’

Blood rushed to Mel’s face. It was going to be that kind of meeting, was it? ‘We’re a charity founded with specific objectives,’ she said. ‘We’ve achieved them more comprehensively than we ever dreamed possible. What are we supposed to do? Pretend we haven’t achieved them, so we can carry on paying ourselves nice salaries?’ This was much harder with Shane listening. She’d planned to find a better moment to break the news. ‘As I say in my proposal, we’ve set the bar for successful single-issue campaigning. The name Orange Peel is now synonymous with smart, effective lobbying. I’m proud of that and I’ll be even more proud if we can also make it synonymous with knowing when to leave the stage in a dignified way.’

‘I’m afraid I’m not really a growing-old-gracefully kind of girl,’ said Xandra. She held out her hand, and Shane leaned across the table to pass her the envelope he’d been carrying. She opened it and pulled out several copies of a stapled document. ‘I certainly don’t believe in turning my back on success. We’ve built something wonderful here and we’re not shutting it down if we can help it. Not on my watch.’ She slid one copy across to Mel, handing the others to Damon to pass round. ‘This is another version of the future, which I asked Shane to write. Do have a glance at it. It contains an interesting proposal, made by one of Cyrus’s Silicon Valley friends. Shane went to see him while the pair of you were in California, didn’t you, Shane?’

He nodded awkwardly, not lifting his eyes from the notepad in front of him. He seemed as uncomfortable as Mel, but that didn’t excuse him. Clearly, they’d been conspiring against her. Except perhaps Damon. Mel hoped she hadn’t completely misjudged the banker with a soul.

She picked up the top sheet, which bore the heading:

Orange Peel FoundationA new direction: programme for expansion

She raised an eyebrow. ‘Expansion? I’ve nothing against expansion in principle. I’m the one, as I hope I don’t need to remind you, who grew this organisation from nothing to where we are today. But what kind of new direction? We’re not like a manufacturer, where you can simply come up with a new product line. We’ve expanded the orange-peel concept all over the world. Our work is literally done.’

‘Actually Shane has discovered an unexpected but bold new route for the next stage of Orange Peel’s journey,’ said Xandra. ‘Perhaps you’d like to explain it yourself, Shane?’

Shane looked like it was the last thing in the world he wanted to do, but no one refused Xandra. He cleared his throat. ‘As Xandra says, while we were in California I had a meeting with Joey Talavera, thanks to Cyrus, who—’

‘The Joey Talavera?’ said Mel, failing to hide her incredulity.

Talavera had made his fortune with the Zype video-conferencing app, but he’d made his name by marrying a member of the Vardashian family. He was now the worldwide media’s favourite handsome billionaire, with a fondness for cameo guest-spots in sitcoms. He was also keen on conspiracy theories: thanks to a recent Netflix documentary that he’d financed and fronted, forty percent of Americans, plus a worrying proportion of the rest of the world, believed the moon landings were fake.

Shane nodded. ‘The one and only.’

If they’d been alone, Mel would have asked why the hell he’d done this without telling her. In front of the board, that wasn’t an option. With the possible exception of Damon, she was clearly the only one in the room to be unaware of the meeting. Drawing attention to her ignorance would only rub in her own humiliation.

‘And what did the one and only Joey Talavera have to say?’

‘It turns out he’s a massive admirer of Orange Peel. He’s followed everything we’ve done and is hugely impressed. It was very flattering. For all of us.’

Mel forced herself to smile. ‘I’m sure.’

‘Anyway,’ Shane continued, ‘he was keen to talk to us because he has a cause of his own, something he’s passionate about, and he thinks we’re the people who can sell it to the rest of the world.’

‘A cause? Please tell me it’s not the moon landings.’ Mel looked around the table for support, but nobody met her eye.

‘Maybe it’s better if you just look at the document,’ said Shane, fidgeting with a strand of his beard. ‘You’ll find the key section on page three.’

Mel flicked to the third sheet, where she saw a paragraph headed ‘the Talavera campaign’. Her eyes widened as she started to read. At the end of the section, she burst out laughing and felt a sudden surge of relief. ‘This is a joke, isn’t it?’ The whole thing was clearly an elaborate prank at her expense, designed perhaps as some kind of tribute to her success.

‘It’s not a joke, Mel.’ Xandra’s face might have lost much of its capacity to show expression, but there was no mistaking her seriousness.

Mel looked around the table again, her relief draining away as quickly as it had come. ‘You’re not actually expecting me to sign up to this nonsense? It flies in the face of everything we’ve ever stood for. There’s no way I’d let Orange Peel trash its own legacy like this. How could you ever think I’d stand by and allow my foundation to sell its soul?’

‘I don’t, Mel,’ said Xandra. ‘None of us do. That’s why, when Joey Talavera reached out to Cyrus, we asked Shane to take the meeting. We knew you’d refuse to contemplate it, because that’s the way you’re made. Your sense of principle is admirable. But you have to know that we, as a board, are of one mind on this: we’re not prepared to put our staff on the street and dismantle this wonderful organisation that we’ve all had a hand in building. So I’m afraid, if you’re certain you’re unable to go down this route, we’ll need your immediate resignation.’

Mel was struggling to breathe. Her mouth had gone dry, her head throbbed and she thought she might pass out. She looked at Damon, but his eyes were fixed on his own copy of Shane’s document. They really were all in this together.

Xandra held out her hand for Mel’s copy of the Talavera document and tucked it back into her folder. ‘Of course it will be an entirely amicable parting of the ways, with no public mention of any disagreement. You can work a respectable notice period, so none of the staff need know. You’ve had a long and brilliant run, and nobody would expect you to stay forever. I’m sure you’ve got one more big job in you. Go off and do that, with our blessing. Obviously we’ll need you to sign this confidentiality agreement, otherwise it might be tricky for us to give you the reference you’d need.’ She slid another set of printed papers across the table. ‘But I’m sure that won’t be a problem, will it?’

Mel blinked. Xandra was offering her a pen.

‘It’s all right. I’ve got my own.’ She was conscious of speaking in a dazed whisper. This was deeply degrading, but what other option did she have? To make a scene and insist on staying in the job that she was planning to abolish anyway? She had clearly lost the support of the treacherous Shane and there was no point in appealing to the rest of her staff, even if they had the power to support her: once they knew they were all doomed under her leadership, they would back Shane’s coup. She tried to focus on the new paperwork.

‘The terms are very generous, as you can see,’ Xandra was saying. ‘The severance comes with Joey Talavera’s compliments.’

The figure Mel found herself looking at wasn’t so much generous as colossal. She wasn’t a greedy person, and a fortunate start in life had left her with few material wants, but this was a staggering sum. She felt sick at the prospect of agreeing to the deal, but her staff would keep their jobs, she’d have a large lump sum to invest, and the world would just have to make what it could of Orange Peel’s lurch into the realm of insanity. What other choice did she have?

‘Where do you want me to sign?’ she said softly.

Shane, who was clearly familiar with the document already, indicated the place with a stubby, nail-bitten finger.

There was one consolation, she thought, as she scrawled her name. The charity she’d built from scratch might shed its own integrity and become a laughing stock, but it would never persuade the public to sign up to Talavera’s deranged scheme. That was the craziest thing she’d ever seen, and not even an outfit as slick and smart as Orange Peel had a cat in hell’s chance of selling it.

2

Shane wasn’t proud of being a snake. It didn’t come easily to him. He tried to console himself with that thought whenever he felt guilty. It didn’t always work, so a better strategy was to remind himself of all the times Mel had belittled, patronised or undermined him.

She wasn’t a shouter, far from it: she was probably the most even-tempered person in the whole office. She expressed disapproval in a much more subtle way, with a tight little frown, like the shadow of a passing cloud, and then it was gone. She kept any real annoyance to herself, which seemed an admirable quality at first, but then became unnerving.

No one – certainly not her deputy – was allowed into her confidence. Her remarkable level of self-assurance came, no doubt, from a public-school education and an effortlessly top-drawer background: as Shane knew from idle googling, her father was Sir David Winterbourne, former permanent secretary at the Home Office, and her maternal grandmother was the detective novelist Henrietta Maxwell-Wyckes, an early rival of Agatha Christie’s. It gave her an innate sense of superiority that revealed itself in any number of small ways. For example, Mel knew all about Shane’s home life, having met his husband Craig several times, but Shane had no idea if Mel had a partner. She said ‘we’ occasionally but, if he fished for more detail, she clammed up. Perhaps there was a select inner circle permitted to know such information, but he – educated at an East Lancashire comprehensive – was clearly not a member.

She looked down on him even when she praised him. When he first got the job, she introduced him to visitors as ‘my clever young deputy’, which he heard initially as a compliment, but she continued to say it without let-up when he’d been there two or three years, and it began to irritate. No CEO would talk proudly about their ‘clever deputy’: that would highlight an obvious threat. But a ‘clever young deputy’ was no threat. She might as well be patting the head of a child.

At other times she’d refer to ‘you young people’, with a wave of the hand that grouped Shane with the rest of the staff. It masqueraded as self-effacement, lampooning her own middle age, but it also emphasised the gulf between herself and everyone else. It came up with anything related to IT. ‘You young people are so good with all this modern technology,’ she’d say, and it was true that her own abilities were woeful. But she created the impression that knowing your way around a computer was for little people, while she conserved her energy for higher matters.

When they discussed it at home, Craig said Shane was too sensitive, hearing slights that weren’t intended. But Shane knew Mel didn’t really think he was clever. One time, he talked about their aim for some target or other going awry, which was one of those words he’d mainly seen written down, and it came out as ‘oary’ instead of ‘a-rye’. On another occasion, he made the mistake of pronouncing ‘hyperbole’ as ‘hyper-bowl’. Mel wouldn’t let either of them go. Months after the initial faux pas, she was still finding ways of working those words into conversation so she could mispronounce them.