8,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Lightning Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

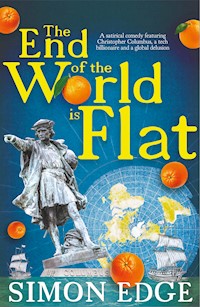

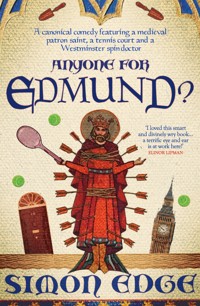

They dug up his bones. They didn't know he had a mind of his own. 'I loved this smart and divinely wry book… what a terrific eye and ear is at work here!' ELINOR LIPMAN Under tennis courts in the ruins of a great abbey, archaeologists find the remains of St Edmund, once venerated as England's patron saint, but lost for half a millennium. Culture Secretary Marina Spencer, adored by those who have never met her, scents an opportunity. She promotes Edmund as a new patron saint for the United Kingdom, playing up his Scottish, Welsh and Irish credentials. Unfortunately these are pure fiction, invented by Mark Price, her downtrodden aide, in a moment of panic. The only person who can see through the deception is Mark's cousin Hannah, a member of the dig team. Will she blow the whistle or help him out? And what of St Edmund himself, watching through the prism of a very different age? Splicing ancient and modern as he did in The Hopkins Conundrum and A Right Royal Face-Off, Simon Edge pokes fun at Westminster culture and celebrates the cult of a medieval saint in another beguiling and utterly original comedy.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

Praise for Anyone for Edmund?

‘I loved this smart and divinely wry book, with its perfect marriage of archaeology, patron sainthood, and 10 Downing Street dirt. Has there ever been a more delightfully cynical political hack than Mark Price, or a more narratively rewarding neurotic prime minister than Marina Spencer? Long live them both! What a terrific eye and ear is at work here!’

Elinor Lipman

‘A wildly inventive romp, rich in history and bunk’

Rose Shepherd, Saga Magazine

‘Anyone for Edmund? is gripping, funny and richly entertaining. This is not only a compelling read, but also a story grounded in real history and the genuine questions of national identity that are still thrown up by the legacies of medieval patron saints – and St Edmund in particular. While this book is fiction, at the heart of it is a truth every historian knows: the past is very much alive’

Dr Francis Young, author of Edmund: In Search of England’s Lost King

‘Fantastically witty, and utterly unique. Who knew that a story about a royal saint, a bunch of archaeologists and the shenanigans of modern politicians, played out against the rich tapestry of medieval history, could be so entertaining? I laughed my head off. A perfect balm for our troubled times’

Maha Khan Phillips

Simon Edge was born in Chester and read philosophy at Cambridge University. He was editor of the pioneering London paper Capital Gay before becoming a gossip columnist on the Evening Standard and then a feature writer on the Daily Express, where he was in addition a theatre critic for many years. He has an MA in Creative Writing from City University, London, where he has also taught literary criticism. He is the author of three previous novels: The Hopkins Conundrum, longlisted for the Waverton Good Read Award, The Hurtle of Hell and A Right Royal Face-Off. He lives in Suffolk.

Published in 2020

by Lightning Books Ltd

Imprint of EyeStorm Media

312 Uxbridge Road

Rickmansworth

Hertfordshire

WD3 8YL

www.lightning-books.com

Copyright © Simon Edge 2020

Cover by Ifan Bates

The moral right of the author has been asserted. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Printed by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY

ISBN: 9781785631917

for Ezio,my treasure in the loamy earth

Contents

Timeline

Story

Afterword

By the same author

TIMELINE

c500

The Wuffing dynasty arrives in East Anglia from Jutland

c633

Monastery founded at Beodericsworth by Sigebert, king of East Anglia

c841

Birth of Edmund

854

Edmund crowned king of East Anglia at Bures

865

‘Great Heathen Army’ arrives in East Anglia from Denmark

869†

Edmund defeated and killed by the Danes

c900

Edmund’s body brought to Beodericsworth

c925

Beodericsworth’s name changed to St Edmunds Bury

c986

French monk Abbo of Fleury writes the first life of St Edmund

1002

Massacre of Danes in England ordered by Ethelred the Unready on St Brice’s Day

1010

Body of Edmund temporarily moved to London after the Danes sack Ipswich

1013

Body of Edmund returns to Bury

1013

Swein Forkbeard, king of Denmark, successfully invades England, named king

1014

Death of Swein in Gainsborough, Lincolnshire

1020

Swein’s son King Canute founds an abbey dedicated to St Edmund at Bury

c1065

Abbot Leofstan opens Edmund’s tomb and is paralysed

1066

William of Normandy conquers England and visits Bury early in his reign

1097

St Edmund declared patron saint of England

1153

Prince Eustace, eldest son of King Stephen, dies in Cambridge after dining at, and then looting, Bury

1173

Forces loyal to Henry II, under the banner of St Edmund, defeat a Flemish mercenary army at the Battle of Fornham

1189

Richard I prays at St Edmund’s shrine on the eve of the Third Crusade

1192

William de Burgh founds St Edmund’s Priory in Athassel, Ireland

c1193

Abbot Samson tells the Barons of the Exchequer that they can come and strip St Edmund’s shrine, to raise funds to ransom the imprisoned Richard I, if they dare. Nobody does.

1282

Llewelyn ap Gruffudd, the last Prince of Wales, killed at the Battle of Orewin Bridge

1296†

Edward I massacres the entire population of Berwick-upon-Tweed

1300

Welsh nobleman Rhys ap Rhys surrenders to Edward I’s forces while the king is at Bury

1350

Edward I visits St Edmund’s shrine for the sixth time; St George named as patron saint of England

1376†

Richard of Bordeaux (later Richard II) invested as Prince of Wales

1433

The young king Henry VI makes a pilgrimage to the shrine of St Edmund and stays for four months

c1435

John Lydgate, monk of Bury, writes the life of St Edmund

1539

Bury Abbey shut by Henry VIII, Edmund’s body disappears

1914

New cathedral consecrated amid the ruins of Bury Abbey

1992†

Windsor Castle badly damaged by fire

1995†

Princess Diana goes on national television blaming Prince Charles’ adultery for the breakdown of their marriage

†20 November

A cry of triumph rose up from the western end of the dig, closest to the abbey ruins. As soon as she heard it, Hannah dropped her trowel, blinked for a moment in the woozy head-rush of standing up too quickly, then hastened over to where Magnus and the other senior members of the team, each with a telltale strap of sunburn on the backs of their necks, squatted around a trench. For once, she forgot about the creaky back that always played up after she spent too long crouching in the same position and made her first few steps into more of a waddle than a walk. This was not the moment to bother about that.

It was day four of the dig, and its leaders had known where to look from the end of day one. Once the mesh fence around the three abandoned tennis courts had been taken down and the top layer of asphalt, with its faded white lines marking out three forlorn sets of baselines, sidelines and service boxes, had been scraped off with a mechanical digger, they had embarked on the geofizz. That was what Hannah called it, after years of watching Time Team, but the professionals stuck strictly to ‘geophysics’. Whatever it was called, it involved an electrical probe to measure resistance, a magnetic survey to map all kinds of things in the soil, not just metal, and ground-penetrating radar. The whole process produced three different maps of the site which could be laid on top of one another, providing pointers for anyone skilled enough to interpret them. Hannah, who was one of the community volunteers welcomed onto the dig to maintain good local relations, could not tell one dark shadow from another, but she was digging alongside plenty who could.

Looking for a coffin-shaped object should have been easy, were it not for the fact that they were searching for it in a graveyard. For five hundred years, all the monks of an abbey the size of a town had been buried here, between the east end of the great church and the infirmary. They were not so much looking for a needle in a haystack, as a strand of hay. Fortunately, it was not completely hopeless. From what Magnus, the youthful volunteer coordinator, had explained, the monks tended to be buried in lead coffins, whereas the object they were looking for was a wooden ‘feretory’ – or portable shrine – adorned with gold and locked in an iron box. The iron would have disintegrated long ago, but the metal would leave traces in the ground that the geophysics could discern, and the gold adornments ought also to have survived.

Sure enough, the geophysics had pointed to the likely place, with iron traces delineating an area of the right shape and size, over by the remains of one of the little semi-circular chapels that protruded from the ruins of the presbytery. That location made logical sense: the monks had not had far to lug their sacred burden as they hurried to hide it from Thomas Cromwell’s sixteenth-century Taliban.

The discovery did not mean that Hannah and her colleagues could all simply pile in with shovels, like cartoon pirates racing to unearth a chest of doubloons. As Magnus never tired of repeating, this was a one-off opportunity for the site to give up its secrets before the ground was closed up again and it must not be squandered. There was at least half a metre of earth to be sifted meticulously before they got near the right level, and there was also the rest of the site to be investigated. ‘It’s an area of approximately one thousand square metres or, in layman’s terms, the size of three tennis courts,’ he said. Hannah laughed, but everyone else groaned.

She had been given a trench at the north-eastern corner of the site, farthest from the spot that looked so exciting in the geofizz. It was on a small brow before the land fell abruptly away towards the children’s playground and the tiny chalk stream that bounded the Abbey Gardens. This river had once been big enough to turn the mill that supplied the whole town with flour, and also to carry the great limestone blocks from the quarry at Barnack, on the other side of the Fenlands, with which the greatest church in Christendom had been built. Those blocks were all gone now, and all that was left of the abbey buildings were the misshapen lumps and towers of flint rubble that had formed the core of thick walls and soaring pillars. The little outcrop where she was working had most likely been built up at some much later stage to create a suitable plateau for the tennis courts. She would therefore have deeper to go before she reached anything interesting, but it also meant she was at less risk of doing any harm. In any case, she could hardly volunteer for a dig and then complain about the amount of digging she had to do.

It was warm work, with the permanent yeasty fug from the town’s Victorian brewery sitting heavy in the air. She fretted at first that she might miss something important, given that everything looked much the same when it was caked with earth. Under Magnus’ tutelage, however, she learned that there was no danger of that, provided she was painstaking. ‘Anything that isn’t earth is either a pebble or an artefact,’ he told the group of half a dozen volunteers, fiddling with his man-bun as he spoke. It had a habit of falling out and Hannah reckoned it needed a pair of chopsticks to secure it, but that would doubtless spoil the look. ‘Just make sure you sift every trowelful of earth and examine every object properly. Remember, your brush and your pail of water are your friends here.’

It was acceptable to hack at a decent lick through the topsoil, which was not so different to digging her own garden. After that, the earth needed removing layer by layer, with each few centimetres kept in its own bucket so you knew which order to put it all back. At her corner of the site, Hannah was following the line of the infirmary wall: to her great relief, no one had the slightest desire to open the monks’ graves, and it was the stuff around the outside of the cemetery that they cared about. At first she got excited at every piece of broken pottery, until she realised she had yet to dig past the twentieth century. After that she reined in her expectations and could not quite believe it when she unearthed a copper belt-buckle, an iron key and a piece of yellow-and-black Cistercian ware which Vernon, the most senior archaeologist on the dig, identified as Tudor. She could see why people got hooked on this kind of thing.

She was so caught up in her own discoveries – the extraordinary thought that she was the first person in five hundred years to handle this shard of pottery or the lead bowl she found an hour or two later – that she forgot all about the serious business happening over by the presbytery. Then came that exultant hullabaloo and suddenly she remembered again, and it was thrilling, like being in the Valley of the Kings when Carter and Carnarvon first gazed on the face of Tutankhamun. Hopefully their own find would not come with a curse.

Vernon and another of the proper archaeologists, a thirty-something woman with blue hair called Daisy, were down on the floor of the excavation, about a metre below ground level, with everyone else looking on, either crouched on their haunches or leaning into the pit. They watched as Vernon gently prised an object from the soil and reached for his brush to dust it clean. As he did so, it caught the light of the hot July sun with the unmistakable gleam of gold. Having brushed off the worst of the dirt, he now held it up for them all to see: it was a crucifix.

Meanwhile Daisy was digging on, carefully now, with a brush and the tiniest of trowels. ‘Vernon!’ she said urgently, and he turned back to see. Those crouching and craning above them collectively leaned a little closer too.

Vernon was using his brush now too, and it was hard to see what the pair of them were doing because first his head was in the way, then hers. Then they both sat back on their heels, revealing their find. A dozen diggers, professional and novice, gasped in unison, and one of the younger volunteers stifled what sounded like a sob. Hannah felt every tiny hair on the back of her neck stand to attention.

They all stared in wonder, and the half-buried skull that Vernon and Daisy had unearthed grinned back at them.

Mark Price peered idly into the window of Suits R U in Victoria Street and was momentarily taken back to his schooldays when he saw his own name, or a close approximation of it, on the promo poster between two pin-striped mannequins. 25 PER CENT OFF MARKED PRICE.

About twenty-five years ago, some bright spark in his class had seen that exact same wording – not twenty percent or thirty – on a school trip to Colchester Castle and had spent the rest of the day calling him Twenty-Five Per Cent Off. ‘Oi, Twenty-Five Per Cent Off!’ Then shortened to, ‘Give us a crisp, Twenty-Five Per Cent.’ It shrank still further, first to Twenty-Five and then to plain Twen by the end of the day. With their teenage capacity to find hilarity in everything, this had been the funniest thing in the world for his little group, including to Mark, and he had revelled in the prospect of a proper nickname. Twenty-Five Per Cent was a rap name. How cool was that?

But the trip was at the end of term and everyone else had forgotten about Mark’s new name by the start of the next one. He had the sense to know he could not revive it himself; that would reek of desperation. So he remained Mark Price, and only occasionally – it tended to be when he was in the throes of self-pity – did he allow a piece of signage to trigger the wistful memory of the time when he nearly had a nickname.

Today was no exception, mood-wise. It was a sign of his general dejection that he was mooching in shop windows in his lunch hour, rather than working through. On paper, being a special adviser to the sainted Marina Spencer was his dream job, particularly with her career on such a spectacular ascendant. Unfortunately, he had learned there was a strong inverse relationship between the level of Marina’s public prominence and his own wellbeing. These days the atmosphere was so poisonous he could hardly bear to be in the office.

After graduating in history from the LSE, he had successfully applied to the BBC. Following a short stint on news, he had spent most of his career producing programmes at the World Service, latterly a thirteen-minute, once-a-week drama set in a diverse street in North London, where all the ‘residents’ spoke just slowly enough for a global English-language audience to understand. He told people at parties that he produced a radio soap with ten times more listeners than The Archers, which was true, even if he had never actually met anyone outside the BBC who recognised its name.

Despite that modest success, he was unfulfilled. He was beginning to feel it in earnest when he turned thirty-five and he promised himself he would get out of his rut before forty came over the horizon. Besides, the pay was embarrassing. He must be able to do better.

He had always followed current affairs and, while his journalistic life was hardly All The President’s Men, he had long envied those distant colleagues who worked the Westminster beat. They knew how the world really worked, they mixed with those who ran or aspired to change it, and sometimes they jumped the narrow divide between their own world and the one on which they reported. Privately, Mark thought he could do the job just as well as they did, but he had taken the wrong road years ago, if that was his ambition. It had seemed a brilliant achievement to get into the BBC – and it really was, there was no doubt about that – so he did not worry too much about not entering the most exciting part of it. He could move from his backwater to more significant positions, he assumed, but he was mistaken. His soap might be popular among students of English in Tashkent and Ulan Bator – they wrote and told him so – but he might as well have been in Outer Mongolia himself, for all that he impinged on the consciousness of domestic programme-makers.

All this steadily became clearer as the years passed. By the time he realised he was at a dead end, it was too late to do anything about it. He fell into self-pity for a while, then bitterness for a while longer, but eventually made a plan. When redundancy was offered in the umpteenth round of cuts, he felt he had served a long enough stretch to make the terms worthwhile, so he decided it was time to give his scheme a go.

His idea was simple. While younger and smarter men and women jostled for position at the court of the two main political parties, the likes of Mark had a better chance with the minority ones. As fortune would have it, his own sympathies were closely aligned to an outfit in the trough of its popular fortunes. An ill-advised coalition with the Tories after the end of the New Labour years had seen the centrist Eco-Dem Alliance almost wiped out in the House of Commons, with its polling down to single figures, and it was the most reviled political party in Britain when Mark offered his services as an experienced ex-BBC producer. Just as he anticipated, its senior staffers were surprised and pleased; in fact their gratitude was borderline embarrassing.

At first, all went well. With party morale at rock bottom, all the brightest operators were long gone, putting their government experience to lucrative use in corporate jobs or consultancies. Those who remained saw themselves as the true believers, made of too stern stuff to cut and run just because times were hard; everyone else saw them as no-hopers without a chance of getting a job anywhere else. They were in no way energised or optimistic. They toiled on, wearing their new opprobrium with grim forbearance, and entertaining few, if any, expectations of an improvement in fortunes. Veterans of the old days, they had always been content to be a tiny, ill-resourced band of misfits, and now they were back in that comfort zone. Nevertheless, it proved a useful training ground for Mark, who was free to learn his new trade without any pressure to achieve. He settled in easily, enjoying the change of scene and not minding being part of such a diminished political force, because it was all new for him.

Then, suddenly, everything changed. After years of chaos following the referendum that had divided the country in two, a majority Conservative government looked set to hold power for a full parliamentary term. But the mass defections prompted by the Brexit food riots obliged a deeply distrusted prime minister to go back to the country, and the resulting election was the perfect storm of which third parties always dreamed. The wrangling Labour Party and the freshly loathed Tories were each wiped out, allowing the Alliance to come through the middle and form its own government, in coalition with the Scottish National Party (on condition another referendum on independence was held within three years), Plaid Cymru and the SDLP. Its leader, the folksy, teddy-bearish Morton Alexander, took office as Britain’s first non-white prime minister.

The party’s surprise triumph owed a good deal to the formidable media skills of a politician who had been a member of the European Parliament throughout the coalition years, and was therefore untainted by them. She was largely unknown except to the most committed political trainspotters. A single appearance on Have I Got News For You a few months before the election changed all that. Her elegant dismissal of an elderly actor with antediluvian views on race went viral, so much so that her put-down – ‘Yeah, no, I really wouldn’t’ – became an instantly recognisable catchphrase. Her appearance was followed by a star turn on Question Time, and the country could not get enough of Marina Spencer.

With her shock of white, pixie-cut hair and her clear, unlined skin, she did not fit the identikit mould, and was a fluent and lucid performer. She had the gift of talking human, as the political cliché had it, and she did it while exuding good humour. While other politicians frowned and blustered, she always had a look of amused benevolence on her face, even when talking about the need to tackle the climate emergency or the wealth divide. This infectiously agreeable demeanour made it seem as if a brighter future really was possible, lifting the mood of a depressed nation. The Alliance’s nationalist coalition partners struck a hard bargain, dividing the great offices of state among them as the new government took office, and Marina had to make do with secretary of state for culture. But it was widely understood that she personally would punch above that department’s weight, particularly when it came to media profile. As the new government took office, the backroom staff from the previous coalition years flocked back from their corporate jobs and consultancies to take up posts in Downing Street, and Mark was disappointed to find there was no room for him there. Instead, in what he was assured was the highest compliment the party could bestow, he was dispatched to serve Marina.

Inevitably, there was a great deal more pressure. In the Alliance’s wilderness years, his job had been a quest for attention, for an acknowledgement, however fleeting, that the party still existed. This was dispiriting at first, but once he understood that any such glimmer of interest would happen no more than twice a month, and that nobody in the party hierarchy expected anything more, he settled into a comfortable working routine.

In government, the situation could scarcely be more different. The pace was frenetic and the scrutiny constant, even in a ‘soft’ department like Culture. It was exciting, of course, to be at the centre of everything. This was what he had craved, in all his years of frustration. Making waves in Whitehall beat being big in Ulan Bator. The problem was Marina, a workaholic divorcee who showed no trace in private of the good humour she projected on television. Her bad temper was such a permanent feature that Mark could not at first fathom why he had ever imagined her to be infectiously cheerful. It took a week at her side, soaking up her stress, demands and frequent rages, before he realised the source of his confusion: the simple styling pencil that she carried in her make-up bag. By marking her eyebrows half a centimetre higher up her forehead than they naturally were, she gave herself an expression of permanent levity, whatever her actual mood.

This discovery would have been funny, had not laughter felt like an indulgence from a bygone existence. Marina Spencer was the most neurotic person he had ever met. Her anxiety focused primarily on her media appearances, which was unfortunate, since she was the government’s star media performer. The fact that she always sailed through, that she could do no wrong in the eyes of the public and was therefore seen as untouchable by journalists, did nothing to calm her nerves. If anything, it made them worse. Every time she triumphed, she became all the more certain that she was heading for calamity the next time – like the terrified air traveller who thinks they have cheated the odds with every safe landing. Mark had a private theory that, somewhere in her childhood, she had been told pride always came before a fall, and she was now a permanent hostage to that dictum. All her staff were hostages to it too, for her way of dealing with anxiety was to carry out endless rehearsals before each appearance, demanding briefings on every conceivable subject. It fell mainly to Mark to prepare them. She would demand them at all hours of the day and most hours of the night, since she was also an insomniac and expected her staff to be the same. In public, she was a passionate champion of workers’ rights, making an attractive case that collective wellbeing ought to be taken just as seriously as economic prosperity when assessing the health of society. In private, she was apt to berate her own staff for laziness if they sloped off before midnight. ‘But Marina,’ protested Mark, on one of the few occasions when he dared stand up to her. ‘It is New Year’s Eve.’

He naively assumed he could share his frustrations with his two closest colleagues, who were at similar beck and call and exposed to all the same caprices. This was a mistake. To twenty-something Karim, slim, intense and precision hair-gelled, who had come back from Brussels with Marina, and Giles, a perma-vaping, thirty-five-year-old veteran of the old coalition, Mark’s exploratory eye-roll of exasperation at her latest unreasonable demand was a sign of disloyalty. It branded him as Not On Marina’s Side, the worst of all faults. Their fealty to their queen was ostentatious and absolute. Karim trotted half a pace behind her, clearing the unworthy from her path with a ferocious death-stare. Giles, with a hipster moustache that lavishly outgrew his beard, giving him the look of a ginger King George V, was more outwardly affable, but his smile had an unnerving tendency to vanish once his mistress was no longer there to see it. Between them, they froze Mark out, casting him back into a metaphorical Outer Mongolia, without the consolation of his soap fan base.

Karim and Giles were competitive with each other, engaging in constant one-upmanship over who took the fewest days’ annual leave. They were all entitled to six weeks, but the pair of them both claimed to have taken three or four days, at most. Even then, Karim maintained he only took his because his grandmother died. They were also determined to expend the maximum possible effort in Marina’s service, to show they were doing her bidding. Thus it was not enough for Mark to secure coverage in The Guardian for Marina’s thoughts on national parks, television licensing or local arts funding. As far as they were concerned, when the story appeared, it had to be press-released.

‘But…why?’ said Mark, genuinely puzzled.

Karim and Giles looked at each other, puzzled that he should be puzzled.

‘Er, so that journalists know about it?’ said Karim.

Like any true millennial, he communicated in up-speak, but his was not a solicitous, are-you-with-me? upward inflection. In Karim’s delivery, it had far more of an accusatory, how-can-you-not-know-that? edge.

‘They know anyway,’ said Mark. ‘It’s in The Guardian.’

‘I’m talking about journalists who don’t actually work for The Guardian?’

‘Trust me, they’ll see it. It’s a journalist’s job to read the papers. And honestly, in fifteen years working for the national media’ – international, he might have said, never forgetting Ulan Bator – ‘I’ve never seen a press release announcing that there’s been a story in a newspaper.’

‘Just do it, buddy,’ said Giles, making it two against one. ‘It’s what Marina wants.’

That was always the killer line, the argument that brooked no dissent. Mark was forced to swallow what little was left of his pride and do their bidding.

Karim, by virtue of having worked for Marina the longest, behaved as if he was Mark’s superior. Mark was wary of challenging this, because it would have meant appealing to Marina, and he had no confidence that she would take his side, even though his contract made it clear that he reported to her alone. When Karim decreed that Mark should attend a training course designed for newcomers to public relations, called ‘How to Spot a News Story’, he acquiesced for the sake of a quiet life, because it would at least mean a day away from the poisonous environment of the office. The trainer was an amiable ex red-top hack who treated Mark as a colleague rather than a student, mining him for anecdotes from his BBC career for the benefit of the genuine rookies on the course. ‘What the hell are you actually doing here?’ he asked discreetly, during a mid-morning break for coffee and biscuits.

‘Don’t ask,’ said Mark, and the guy seemed to understand.

A few weeks later, Mark broke his leg when he tripped and fell down a wet flight of steps at Westminster tube station. He knew as soon as he landed that it was bad, and he lay in a bedraggled, painful heap for half an hour before an ambulance arrived to take him across the bridge to St Thomas’s. Inwardly, he was rejoicing. The fracture would earn him a couple of weeks away from the hell-hole.

But bones heal, and now he was back, more ground down than ever by the snarking, finger-pointing and competitive presenteeism. He took refuge in long lunch breaks, even though he knew they reduced him further in his colleagues’ esteem. Lunch hours were for clock-watchers who did dull jobs, for whom sneaking a read of a car magazine in WH Smith’s or browsing the masonry screws in Robert Dyas were the highlight of the day. They were not for the gilded few who had the honour of walking the corridors of power, still less for the chosen ones who served Marina Spencer. But Mark did not care. For the sake of his sanity, that last honour was best enjoyed in doses of no more than three hours at a time, with a decent break in the middle.

Glancing at his watch, he saw that it was nearly two o’clock already, and he turned away from the MARKED PRICE sign to make his way back along Victoria Street. He was swiping his pass through the security gates at the Department of Culture when his phone rang.

‘Ah!’ said his mother.

This was her own personal shorthand for ‘so you’ve actually picked up for once’, and it was true, he could be deliberately elusive. That did not make the greeting any less irritating.

‘Sorry, I won’t be able to talk. I’ve been out for a while already and I’m just about to get in the lift.’

‘Can’t you take the stairs for once so I can tell you this news? It’s something very big and I wanted to tell you before it…’

‘All right then, I’ll take the stairs. You’ve got five floors to tell me.’

‘It’ll do you good.’

Pushing through the swing doors into the stairwell, he was surprised to see how many colleagues took this route, some of them leaping two steps at a time, like it was part of a workout regime. Who knew?

‘Go on then.’ He could hear himself panting into the mouthpiece before he had even reached the first floor. ‘What’s the big news?’

‘It’s Hannah.’

‘Oh yes?’

Hannah was his cousin. They were not close, either in years or friendship. Mark had nothing against her – he had no strong feelings one way or the other – but his mother wanted them to make friends and was under the misapprehension that he would grow to like Hannah better the more he heard about her.

‘You know I told you she’s doing this dig?’

‘Did you?’

‘In the abbey at Bury. I remember distinctly telling you about it. Anyway, I know you’re in a hurry, so the point is – they’ve found him!’

Sweating now, Mark stopped at the second landing.

‘Found who?’

‘Found who! Edmund, of course. Saint Edmund. I told you.’

He did vaguely remember, but he had never quite been sure who St Edmund was. Rather than ask, he had just let her run on.

‘And where was he?’

‘Under the tennis courts. Just where they were expecting.’

‘How did he get there?’

‘The monks must have hidden him there. It’s very close to the ruins of the church itself.’

‘Why did they do that?’

‘Do what?’

‘Hide him.’

‘To keep him safe, I suppose, after the abbey was shut down. In the Reformation, you know. Fifteen-something. You’ll know the details better than me, with your background.’

‘You know that most of my degree was about imperialism and decolonisation, right? Not a lot of Tudors.’

‘You must have done them at some stage. Anyway, that’s how long he’s been there. Nearly five hundred years.’

‘And what does a five-hundred-year-old corpse look like?’

‘He’s more than five hundred years old, you clot. That’s just how long he’s been under the tennis courts. Well, the tennis courts haven’t been there all that time, but you know what I mean. Before that, he was in a shrine in the abbey for five hundred years, so that makes a thousand, and I think he died quite a bit before that. In Saxon times. Are you sure you don’t know all this? If you don’t, you can look it up yourself. I’d have thought you might be googling it already.’

‘I need my phone to google, and I’m using it to listen to you.’

‘Well, you can do it when you reach your desk. It’s a very exciting development. It’ll be all over the news, when they announce it. They haven’t done that yet, and I thought you’d like a…what’s that horrible expression?’

‘A heads-up?’

‘Yes, probably.’

‘Thank you. I appreciate that.’

‘You working for the government, and all that.’

‘What’s that got to do with anything?’

‘Well, he was England’s patron saint, until we got St George.’

‘Was he?’

‘Didn’t you know that either? Are you all right, by the way? You sound badly out of puff.’

He was on the fourth-floor landing now, and he was aware of wheezing into the phone. ‘I’m fine. It’s just that I usually take the lift.’

‘From the sound of it, you should take the stairs more often.’

‘It’s not so long ago I broke my leg, remember.’

‘Is it still giving you gyp?’

‘Sometimes.’ He had certainly become more cautious about exerting himself. ‘Look, I’m nearly there, so I’ve got to go, OK? But thanks for letting me know. It’s a very impressive heads-up.’

‘I thought so too. Quite a turn-up, for your old mum to know what’s going to be on the news before you do, eh?’

‘It may only make the local news.’

‘No, Hannah says they’re getting ready for a big press conference. All the big ones are there – BBC, ITN, Channel 4 News…’

‘Fair enough, I believe you.’ He had reached his own floor now. ‘I really have got to go. Thanks for ringing. And yes, I’ll look him up. St Edmund. Got it. Bye now. Bye…yep, and you…bye…’

He swiped through his messaging apps as he made his way to his desk. There was an alarming stack of new emails, plus texts from Karim, Giles and Marina herself. And now here was Karim, ambushing him before he could reach his desk. His eyes were bright with adrenaline, as if he had been mainlining whatever drama was under way. ‘Where were you? Marina’s been looking for you. We all have.’

He would not rise to it. ‘I’m here now. What’s the crisis?’

‘She needs eye-catching ideas. Every department needs to come up with five before cabinet.’ Karim clearly considered the situation so grave that his voice was not even going up at the end of the sentence.

‘Before cabinet? That’s not till tomorrow morning. Why the big panic?’

Karim’s nostrils flared and his eyes rolled, as normal, upwards-inflected service resumed. ‘Because they need thoroughly thinking through? Like, war-gamed, before she can take them to the actual prime minister?’

‘War-gamed?’ Mark did not bother to hide his smirk.

‘Do you really want to send Marina naked into a hostile cabinet, with everyone just waiting for the chance to stab her in the back?’

‘I think she’ll be wearing clothes. We can all agree on that. There may even be rules about it.’

Karim had his mouth open to reply when the door to Marina’s office flew open. Mark could hear her before he could see her. ‘So where in Christ’s name is he? And don’t tell me “at lunch”. He isn’t paid to be at blasted… Oh, there you are, Mark. At last. Eye-catching ideas! Got it? Christ, I’m going to go naked into that cabinet tomorrow, with everyone just waiting for their chance to stab me in the back.’

Anyone else would be embarrassed to find that the person they were loudly bad-mouthing was in earshot, but that was not how Marina worked. She folded her arms, waiting. Karim mirrored her stance.

It was perhaps not the time to ask why Karim could not come up any eye-catching ideas himself. Instead, Mark said: ‘How about a new patron saint for the whole of the UK? Bringing all four nations together, after the trauma of the past few years?’

Marina’s artificially elevated eyebrows rose a fraction. ‘A new patron saint? Who?’

Until the moment he opened his mouth, Mark had no idea he was going to make this suggestion. As ideas went, it was not so much half-baked as still in the mixing bowl before he had turned the oven on. However, it was entertaining to see Karim swap his look of perma-scorn for grudging attention. ‘St Edmund. They’ve just found him under the tennis courts next to the ruins of Bury St Edmunds abbey.’

‘Why haven’t I been told about this?’ demanded Marina, wheeling on Karim. ‘It’s heritage. I should have been told.’

Even if nothing came of the idea, it would be worth it for that moment alone. Stuttering, Karim plucked his phone out of his pocket and started stabbing at it, as if it might help him defer the blame.

Mark came to his rescue, enjoying the chance to be magnanimous. ‘They haven’t announced it yet. I’ve only just heard it from my, er, contact on the dig. I was talking to them while I was out. Obviously, you know that St Edmund used to be the patron saint of England until he was replaced by St George?’

‘Obviously,’ said Marina, and Karim nodded briskly. Neither of them had any idea.

‘And he’s been hidden for five hundred years, so it’s an occasion for national celebration, and not just for England…’

‘…but for Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland too,’ said Marina. ‘Yes, I can see where you’re going. A unifying figure could be just what we need, especially with another Scottish independence referendum on the cards. But is there any kind of connection? I mean, wasn’t he English? Why should the Scots care about him?’

This was a fair point, and one that Mark himself might have anticipated if he had considered the matter for two seconds, rather than just the fraction of one.

‘Of course we’ll need to build the case. Leave that with me,’ he said. He added a silent prayer to St Wikipedia that he could find some adequate connection.