A Signaller's War E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

As the First World War roared into its second year, 17-year-old Lawrence Ellis marched into his recruitment office and signed up, eager to fight for King and Country. Underage, as so many were, it wasn't until he had cut his teeth in the Royal Field Artillery that Ellis joined the Corps of Royal Signallers. It was some years after the war, however, that the private began to commit his memories to art and words. A Signaller's War includes a poignant selection of Ellis' images, portraying the conditions, experiences and hopes of the common soldier in the trenches of the Western Front. Often humorous, sometimes horrific, always honest, this collection is a unique insight into the life of a young volunteer who grows from a boy to a man during his service, after witnessing the aftermath of the Somme and action at Cambrai. He was not a trained artist, writer or diarist, yet his work demonstrates a skill and sensitivity that will leave the reader breathless.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 209

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

A Signaller’s War

The Sketchbook Diary of Pte L. Ellis

Edited with supporting text by David Langley

For James and Georgia, my inspiration always, and Becky, my light, and, of course, the family of Lawrence Ellis

First published 2016

The History Press, The Mill, Brimscombe Port, Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2016

Diary and sketchbook © The Estate of L. Ellis, 2016. New explanatory text and compilation © David Langley, 2016

The right of David Langley to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

EPUB 978 0 7509 6933 8

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

Preface The Start of It All

1 Very Basic Training

2 A Signaller’s Life for Me

3 France, June 1916

4 Manoeuvres, July to December 1916

5 A New Year, January to April 1917

6 Summer 1917

7 Cambrai

8 Blighty

9 The Return, May to August 1918

10 ‘Gassed last night, gassed the night before …’

11 The End of Hostilities

12 Clearing Up

Glossary of Slang, Anglo-French and Other Army Terms

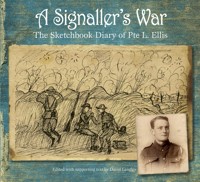

Private Lawrence Ellis, pictured in 1916.

Preface: The Start of It All

Lawrence George Ellis was born on 4 January 1899 in Tottenham, England. His childhood was spent in and around the borough of Enfield and he went to school at Alma Road Boys’ Council School in Ponders End and then at Enfield Grammar School. At 17, he lied about his age and enlisted to fight in the Great War. This book is his account of his experiences.

The remarkable sketches and diaries that Lawrence composed of his time in the trenches of the Western Front are unique in a number of ways. Firstly, to have such a large collection of sketches and maps (over 1,700) must make for one of the most detailed visual accounts of the Great War by a front-line Tommy. There are many thousands of war diaries and detailed accounts of soldiers’ experiences available, but I have yet to come across a collection quite like this. Since starting work on the sketches in 2014, I have often speculated as to the time it would have taken Lawrence to complete the work. A good friend, who also happens to be a professional artist, has suggested that each sketch would take approximately thirty to forty-five minutes, with the more architecturally detailed ones taking longer. The maths is quite something: 286 pictures at the start of the account deal with his basic training, his time at Deepcut barracks and his journey to France. The next 713 deal with his first stint of service until he is shipped home in November 1917 after being injured while fighting at Cambrai. The following 167 deal with his convalescence in Britain. The next 280 return to France and Belgium and take us up to the news of the Armistice. The final 258 deal with the clear-up operation after the war until his return to Ponders End in July 1919. This makes a grand total of 1,704 individual sketches (571 in the first ledger, 575 in the second and 558 in the third). Having spoken to his daughter Doreen, she says that, as far as she is aware, Lawrence would draw the sketches in the evening. So, assuming he did three drawings a night, the entire project would have taken him 568 days to complete. Allowing for the occasional night off, this is almost two years of work. The obvious question is what drove Lawrence to do this. Sadly, we may never know the actual reason but one can speculate that there is an element of self-administered art therapy about the project. One doesn’t commit to such an undertaking without feeling a compulsion to do so. Today, we are all too aware of the stresses and strains that combat places upon even the most hardened soldier, and the emotional and mental cost to the individual. Post-traumatic stress disorder is now widely recognised and counselling and support more readily available to service personnel than ever before.

The other way in which this account is certainly unique is the fact that it covers the service career of a signaller during the First World War. As far as I am aware, no such text exists which outlines so precisely the day-to-day operations of those detailed with creating and maintaining communications. I was aware of the role of a signaller before starting this research: the importance of communication for clarification of positions during both quiet periods and intense periods of battle, and the linking of the front line to command HQ through the use of Morse code and the earliest field telephones. What I was less clear about was how much more there was to the signaller’s duties and skills. The use of semaphore and helioscopes seemed like methods from the past, closer to beacon fires and smoke signals than the demands of modern warfare. During the war, it was the Royal Engineers who had the broad responsibility for communications per se, but hundreds of divisions along the Western Front had members of their own corps who were signallers working under the command of divisional operations. The story of the work of these men has largely gone untold and so the account left by Lawrence Ellis is all the more important historically, as it fills in another small piece of the massive jigsaw that makes up operational procedures for both sides in the First World War.

I am often frustrated and annoyed by those who claim a success or a remarkable event or a significant life-changing moment was simply the result of chance or of being ‘in the right place at the right time’. I have never been one to subscribe to the idea that fate dictates our existence. I was always on the side of the pragmatists, the rationalists, those who believed that self-determination had little to do with luck. Yet the start of my journey working on the war experiences of Private Lawrence Ellis, Signaller First Class, 40th Division (later 33rd Division) Royal Field Artillery, was all about being in the right place at the right time, a great deal of luck and fortuitous timing. In other words: chance. Now nearing the end of that journey, I cannot help but reflect that this is entirely appropriate, given the path I have travelled. Lawrence was a lucky man. One could argue that surviving the Western Front for over two years was in itself lucky. He was lucky in attaining a role within his division that so suited his particular talents and abilities. I believe he was fortunate to find a way of expressing his thoughts and reflections upon the conflict that allowed him to deal with the horrors he saw while retaining an obvious sense of humour, and which again made use of his very individual gifts. Of course, application, determination, ability and strength of character have an equally important part to play, but luck was never far away. He was a lucky man in as much as he lived a full, varied and active life, married a woman he so clearly loved, had two wonderful daughters and enjoyed his family right up until his passing on 14 June 1971.

This book is also about communication. It is about one man’s experiences during a conflict that was to engulf large parts of the world and cause the deaths of millions of people. It is a story of a former soldier coming to terms with his experiences and communicating them through words and drawings. It is about a family man, trying to find a way to resolve his internal conflicts and also leave behind a legacy for his children so that they might understand what he went through. In that way, this is also a book about love. Love for one’s comrades, for one’s country and for one’s family.

The need to communicate, to share with others, specific information is at the heart of most, if not all, of what we do in life today. From those now apparently prehistoric days of picking up a pen and writing letters to the spread of social media sites, our basic need to tell each other things we know or have experienced has always been at the heart of any civilised society. The sharing of information is an obvious prerequisite for success in the workplace and personal relationships. And, of course, for the military of any age communication has been and always will be a vital and integral part of any conflict. From the beacons that were lit along the Greek shores alerting Clytemnestra of the fall of Troy to the runners used by the Inca Empire to warn their sun god Atahualpa of the arrival of Pizarro and the Spanish fleet, ancient cultures understood all too well the need for relaying accurate information as quickly as possible so as to stay one step ahead of the enemy. Horns, drums, smoke and light signals have all played their part in communicating vital information to Caesar, to Genghis Khan, to Napoleon. The importance of communication, and especially of accurate and precise communication, is a vital part of any war effort. In 1795 communication was hastened when semaphore telegraphs made their first appearance; Morse code quickly followed in 1835, while the use of the electronic telegraph in 1837 was as big a step then as smart-phone technology and the Internet have proved today in terms of the speed and quality of information received. In 1869, having relied upon the civilian telegraph system, which was operated by the General Post Office (GPO), the British Army instigated the first official Signal Wing, which was then part of the Royal Engineers (RE). By 1884, this had developed into the RE Telegraph Corps. In 1898 wireless telegraphy was introduced, but it was not until 1920 that the Royal Corps of Signals was finally formed and established. Today, the success of a modern army can often be judged by the efficiency and accuracy of its communications. The ability to send and receive signals from a conflict, to alter and adapt orders in response to new developments during an engagement and to relay recent manoeuvres of the enemy, all form part of a vital bridge between command HQ and those on the front line.

This book brings together the service life and experiences of a young signaller in the Great War, Lawrence George Ellis, who was underage, as so many were, when he signed up to join the Royal Field Artillery in 1915. He was in France and Belgium for nearly four years. This book details those experiences and more. It shows how the macro events of the Western Front affect the micro experiences of one man. Lawrence was just into his thirties when he completed his work on the sketches and writing contained within this book.

My first acquaintance with this remarkable collection was in the spring of 2014. I was covering for a colleague within the history department at the school where I teach and I was offered the chance to look at some sketches that a Year 9 student had brought in, which had apparently been drawn by his great-grandfather. Little did I realise then what a unique and vital opportunity I was being offered. The cover lesson was over by 3.30 p.m. but I remained within the classroom until well past 9 p.m., totally captivated by what was laid out in front of me. Since then, my journey has taken me around Europe talking to ex-servicemen (including many signallers), visiting archives and museums, discussing theories with artists and psychologists, and basically attempting to piece together as full a picture as I can of what Lawrence Ellis experienced and why he felt compelled to record, in so vivid a manner, his war experiences.

Of course, in many ways Lawrence is communicating with us now. His recollections, his thoughts, his impressions of the battlefields of France and Belgium speak to us, across the expanse of a century, of the everyday mundane and the unimaginable, extreme horrors that he was witness to in four extraordinary years. The detail within many of the pictures is what first takes the eye. His use of perspective and his naïve figure drawing combine to create a powerful and often moving account of his time in service. This very personal record stands as a testament to his abilities as a writer and artist, and also to his experiences as a young signaller during one of the greatest conflicts the world has ever known.

Here is Lawrence’s story.

1 Very Basic Training

One of the questions I kept coming back to as I worked my way through the pages of text that Lawrence had written was why he had decided to write about and draw in such detail his experiences of the Western Front. I have already mentioned my early musings on the therapeutic nature of the work, but there are also other important questions. Who was he writing for? What were his intentions for the manuscripts once they were complete? Did Signaller Ellis have a far larger readership in mind than his immediate family when he undertook the task? It is in the introduction to the written diaries that I think the answers may lie.

There are so many things that I find very telling and reminiscent of a bygone age within the sketches and the written diaries that it is sometimes easy to overlook their importance in terms of their cultural and social context. The foreword to the first written diary starts with a declaration that says as much about the time in which it was written as it does about the author and the period covered by the collection:

It is a true account with no exaggeration and the only score in which it has been bowdlerized is that of certain adjectives used in conversation. For with certain of the troops, ‘bloody’ was the mildest adjective known and to write down in cold print the name given, to say, a refractory mule, an unpopular N.C.O. or the weather is more than I or any other writer dare attempt.1

This statement is interesting for a number of reasons. Obviously it speaks of an age when profanity was frowned upon, and certainly not accepted as a form of expression compared to our more tolerant attitude today. Just as importantly, though, it made me realise that Lawrence might well have had an eye on getting the diaries published. He was certainly conscious of a readership as he wrote. Indeed, the very term ‘diary’ may be misleading, as this suggests something private and personal, whereas I believe the sketches and the handwritten accounts make up a memoir, if not an autobiography. He often references ‘the reader’. He was clearly conscious of the fact that others would possibly someday read these accounts and it is this that often guides his authorial hand. He writes early on of his intention to inform of the battles that he believes have been forgotten by, at that time, recent history books. He is acutely aware of how many of the ‘smaller’ battles, from Beauchamp to Gonnelieu, from Cambrai to Fifteen Ravine, appear to him to have been forgotten by the public at large and are now only recalled by ‘those that took part in them’. This is certainly a major contributing factor to his work.

What was particularly illuminating was the discovery that his diaries had been rewritten. The first draft was undertaken in 1921 and the draft that has survived and that I have worked with for the past two years is, in fact, the second draft, undertaken nine years later, in 1929–30. Why the gap? Why did he feel the need to return to the work nearly a decade after first completing it? Clearly the passing of time allowed Lawrence himself to reflect further upon his own experiences and memories. In 1921 he was a young man of 22, recently married and doubtless still adjusting to the world back home would be a very different individual to the 31-year-old family man, distanced by a decade from the horrors and misery of the war. In 1921, only two years after finally leaving France, the published books on the conflict rarely offered a critical viewpoint of the war and the national collective memory was still being shaped. By 1930, with Tyne Cot cemetery officially sanctioned by the visit of King George V in 1922, the Menin Gate opened in 1927 and Lutyen’s magnificent Thiepval Memorial under construction, the significance of certain battles and areas had been clearly established within the national psyche. I believe that these diaries are an attempt to redress the balance, or at the very least allow the participants of the more ‘minor’ skirmishes to have a voice and be remembered. The work stands as a reaction to the slowly creeping simplification and generalisation of the war to a few major battles and events retained by the popular awareness of the day.

There is also significance to the fact that it is a decade that has passed. There is something about the very idea of a decade, in a numerical system that works in multiples of ten; it carries a certain cachet that perhaps encouraged a degree of self-reflection – an anniversary with perhaps a little more significance than previous years. It is a time to take stock, to look at progress made, at the memories that remain and the faces that one still retains.

The work, above all, is a very human account and in a way it is a reaction to the more serious, analytical tomes available at the time. The inclusion of so many light-hearted moments is one of the work’s great triumphs. The humour that Lawrence shares with the reader is very evident almost from the first image. This is clearly a deliberate ploy on his part. He wanted to give as full a picture as possible of the day-to-day experiences of a signaller in the First World War. Yet, this was also clearly a cause of some concern for Lawrence, as there appears in the foreword to the written diary this explanation as to why there are quite so many humorous episodes cited:

My narrative does not eliminate the lighter side, as do so many of the post war books. Thus, after reading of my first six months in France, the reader may be inclined to think that it ‘wasn’t such a bad old war’. But reading on, the account of the next few months will cause him to change his opinion.

There is a clear awareness of the work being outside the ‘published’ norm. So how did Lawrence see his work being presented? This is probably the most difficult of the publishing questions to answer. Did he imagine a great volume of 1,800 sketches and over 400 pages of handwritten text to be produced in a stand-alone edition? Did he perhaps believe that the works may be collated into two volumes, acting as companion pieces one to the other? Or did he, as I like to fantasise in my more prosaic moments, foresee a future where someone from outside the family would discover the texts and decide that they were of enough importance and interest to work on them and create a published text of some sort?

Whatever the case may be, I am convinced that Lawrence would wholeheartedly approve of as wide an audience as possible viewing his drawings and writings. It is in the very detail of the work and the inclusion of the mundane and the ridiculous that the true value of this historical document is realised. It is in the juxtaposition of the commonplace with the extraordinary that the real power of the sketches resides. In this chapter, detailing his early training at Aldershot and Deepcut, I have tried to retain the balance between the historically significant and the more day to day. The banality of mucking out stables, the uncomfortable conditions, the meaningless drills and daily marches are all offered up as an insight into the tedium that was, for many recruits, their most enduring memory of their training days. Of course, there are also a great many life-changing events taking place and these are also reflected. The single most significant moment within this chapter, as far as Lawrence is concerned, takes place on 3 November 1915, when he is no longer a driver for the Royal Field Artillery (RFA), viewed as one of the lowest roles within the ranks, but is transferred to the Signallers Section of the 40th Division, RFA. From here on in, his work becomes focused, as does mine, on the training and experiences of a signaller in the Great War and it is this area that makes the sketches an important collection, offering a unique perspective on the history and development of signalling and communication within the war as well as a very personal record of one man’s experiences.

The first sketches in Book 1 of the collection naturally deal with the very first days of Lawrence’s experiences in the army. The naïvety of a 16-year-old whose head has been filled with stories of adventure and derring-do, who expresses disappointment (in the prologue of the written account) that the war had started a year too early for him, is never far from the narrative offered. From the very outset of my work on the sketches I was prone to speculation (never a good road to follow for a supposedly sober perspective on a historical document). Often I caught myself pondering the aesthetic and artistic qualities of the sketches and their shared relationship to the written account of Signaller Ellis’ experiences. Now, with the 20/20 clarity of hindsight, I realise that this served little use or purpose. Even the location at the start of the sketches was trying to tell me to give this self-indulgence a miss – ‘Ponders End’. Yet the temptation persisted. Ponder I would.

Right at the beginning of the diaries, Lawrence details how he came to be assigned to 185th Brigade 40th Division of the Royal Field Artillery. As with so many of the events covered in his writing, an element of chance is brought to the fore:

‘Well, my lad, what Regiment do you want to join?’

‘Oh, any one for three years or duration.’

‘Well, there’s a local Brigade of R.F.A. being formed at Tottenham, what about that?’

‘Right oh, that’ll suit me.’

So the 17-year-old Lawrence made his way to the local recruiting office at Bruce Grove to persuade the powers that be that he was in fact 19 years of age.

One of the most attractive and affecting aspects to the entire collection of sketches is the simplicity of the drawings themselves, particularly the apparently crude attempts at portraiture. Perspectives, landscapes and architecture seem to come easily to Lawrence, whereas the rendering of the human form of men, soldiers in uniform, civilians in their everyday clothes, all seem a little beyond his reach. This is by no means a criticism, as I believe it is that contrast between the detailed and the generalised, between the very precise nature of the surroundings and the casually realised depiction of the men caught within the conflict itself, that creates the most dramatic of impacts on anyone looking at these drawings for the first time. The medical examination sketch offered on the very first page is a case in point. As Lawrence himself describes it:

I found myself in a large room, in which were about a dozen or more would be recruits, divesting themselves of their clothes. ‘Strip!’ barked an officer, seated at a table, at which also sat one or two N.C.O.’s surrounded by various official looking documents.

The reflective, post-war authorial voice seems at odds with the child-like quality of the cartoonish caricatures, either in profile or face on to the viewer, who all share a striking similarity in expression and shape. This pattern is maintained through the entire collection. Specific traits do develop, some individualism is offered, particularly when in duologue but, on the whole, there is an odd anonymity to the figures shown with their identical hairlines, features and habits. (It is striking to this twenty-first-century viewer to note the amount of men with cigarettes hanging nonchalantly out of the corner of their mouths.)

Following various high stepping stunts in a state of nudity, measurements were taken, lengthways and sideways, we were all solemnly sworn in, received our king’s shillings and left the office fully fledged gunners and drivers of the 185th Brigade (Tottenham) Royal Field Artillery. My rank was driver and age was officially nineteen … In one respect I was rather disappointed. Being five foot seven inches in height, I was an inch too short to be designated a gunner and ‘driver’ did not sound very exciting. Nevertheless, I was very happy at having been accepted, for my physique was but puny and it was only by a tremendous effort my chest had been expanded to the required dimensions.