20,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

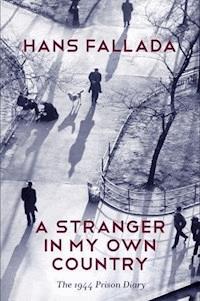

“I lived the same life as everyone else, the life of ordinary people, the masses.” Sitting in a prison cell in the autumn of 1944, the German author Hans Fallada sums up his life under the National Socialist dictatorship, the time of “inward emigration”. Under conditions of close confinement, in constant fear of discovery, he writes himself free from the nightmare of the Nazi years. He records his thoughts about spying and denunciation, about the threat to his livelihood and his literary work and about the fate of many friends and contemporaries. The confessional mode did not come naturally to Fallada, but in the mental and emotional distress of 1944, self-reflection became a survival strategy.

Fallada’s frank and sometimes provocative memoirs were thought for many years to have been lost. They are published here for the first time.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 565

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Introduction

The 1944 Prison Diary

Notes

The 1944 Prison Diary

The genesis of the Prison Diary manuscript

Chronology

Index

End User License Agreement

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Begin Reading

Print Page Numbers

ii

iii

iv

vi

vii

viii

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

224

225

226

227

228

229

230

231

232

233

234

235

236

237

238

268

269

270

271

272

273

274

A Stranger in My Own Country

The 1944 Prison Diary

HANS FALLADA

Edited by Jenny Williams and Sabine Lange

Translated by Allan Blunden

polity

First published in German as In meinem fremden Land. Gefängnistagebuch 1944

© Aufbau Verlag GmbH & Co. KG, Berlin 2009

This English edition © Polity Press, 2015

The translation of this work was supported by a grant from the Goethe-Institut London which is funded by the German Ministry of Foreign Affairs

Polity Press65 Bridge StreetCambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press350 Main StreetMalden, MA 02148, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-0-7456-8156-6

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Fallada, Hans, 1893-1947.

A stranger in my own country : The 1944 Prison Diary, 1944 / Hans Fallada. pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-7456-6988-5 (jacketed hardback : alk. paper) 1. Fallada, Hans, 1893–1947--Diaries. 2. Authors, German--20th century--Diaries. 3. Authors, German--20th century--Biography. 4. Prisons--Germany--Neustrelitz--History--20th century. I.nTitle.

PT2607.I6Z46 2014

833’.912--dc23

[B]

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website: politybooks.com

Introduction

On 4 September 1944 Hans Fallada was committed to the Neustrelitz-Strelitz state facility, a prison for ‘mentally ill criminals’ in Mecklenburg, some seventy miles north of Berlin, where he was to be kept under observation for an indefinite period of time. His fate was entirely uncertain.

This was not the first time that this son of an Imperial Supreme Court judge found himself behind bars. In 1923 and 1926 he had already been jailed for six months and two and a half years respectively on charges of embezzlement. In both cases his drug addiction had been a key factor. In 1933 he had been accused of involvement in a conspiracy against the person of the Führer, and had been taken into protective custody for eleven days. In the autumn of 1944 the charge was a different one: Fallada was accused of having threatened to kill his ex-wife on 28 August 1944.

The divorce had been finalized on 5 July 1944. Yet the couple continued to live together, with others, on the farm in Carwitz: Anna (Suse) Ditzen in the house with their three children, her mother-in-law and a constantly changing number of bombed-out friends and relatives, Hans Fallada in the gardener’s flat in the barn. On that Monday afternoon at the end of August the heavily intoxicated Fallada fired a shot from his pistol during an argument. Anna Ditzen took the gun away from him, threw it in the lake and alerted Dr Hotop, the doctor from the neighbouring town of Feldberg. Both Fallada and Anna Ditzen later testified that the gunshot was not intended to kill. Dr Hotop sent the local police constable to escort his patient to Feldberg to sober up. The matter might have ended there, but the story came to the ears of an over-zealous young prosecutor. He insisted on having Hans Fallada transferred to the district court in Neustrelitz for questioning. On 31 August the accused was ordered to be ‘temporarily committed to a psychiatric institution’. On 4 September the gates of the Neustrelitz-Strelitz state facility closed behind Hans Fallada. He was placed for an indefinite period in Ward III, where insane or partially insane criminals were housed. It looked like the end of the road for him: an alcoholic, a physical and mental wreck, an author who was no longer capable of writing.

Yet Fallada used his time in prison to recover from his addictions – and to write. As early as 1924, when he was in prison in Greifswald, he had kept a diary as a form of self-therapy. So now he requested pen and paper once more. His request was granted. He was given ninety-two sheets (184 sides) of lined paper, approximating to modern A4 size. As well as a series of short stories, Fallada wrote The Drinker. On 23 September, noting that his novel about alcoholism remained undiscovered, he was emboldened to start writing down his reminiscences of the Nazi period. He was one of ‘those who stayed behind at home’ (as distinct from those writers and artists who went into voluntary exile when Hitler came to power): he spent the years of the Third Reich in Germany, for the most part in rural Mecklenburg, where he ‘lived the same life as everyone else’. Now he wanted to bear witness. Here in the ‘house of the dead’ he felt the time had come to settle personal scores with the National Socialist regime, and also to justify the painful compromises and concessions he had made as a writer living under the Third Reich.

In the autumn of 1944 the catastrophic war was entering its final phase, and the collapse of Hitler’s Germany was clearly imminent. The Allies were approaching from all sides, American troops were at the western frontier of the German Reich, while the Red Army was advancing towards East Prussia. At the same time the Nazi regime was stepping up its reign of terror and tightening its stranglehold on the German people. In committing his thoughts and memories to paper, Fallada was now putting his own life at risk.

Surrounded by ‘murderers, thieves and sex offenders’, always under the watchful eye of the prison warders, he wrote quickly and frenetically, freeing himself, line by line, from his hatred of the Nazis and the humiliations of the past years. He proceeded with caution, and in order to conceal his intentions and save paper he used abbreviations – ‘n.’ for ‘nationalsozialistisch’ (National Socialist), for example, and ‘N.’ for ‘Nazis’ or ‘National Socialism’ – while the minuscule handwriting was enough in itself to deter the prison warders. But Fallada went further in his efforts to ‘scramble’ the text, turning completed manuscript pages upside down and writing in the spaces between the lines. The highly compromising notes, part micrography and part calligraphic conundrum, became a kind of secret code or cryptograph, which can only be deciphered with great difficulty and with the aid of a magnifying glass.

On 8 October 1944, a Sunday, Hans Fallada was allowed out on home leave for the day. He smuggled the secret notes out under his shirt.

The 1944 Prison Diary

(23.IX.44.) One day in January 19331 I was sitting with my esteemed publisher Rowohlt2 in Schlichters Wine Bar3 in Berlin, enjoying a convivial dinner. Our lady wives4 and a few bottles of good Franconian wine kept us company. We were, as it says in the Scriptures, filled with good wine, and on this occasion it had had a good effect on us too. In my case you couldn’t always be sure of that. The effect wine had on me was entirely unpredictable; generally it made me belligerent, self-opinionated and boastful. But this evening it hadn’t, it had put me in a cheerful and rather jocular, bantering mood, which made me the ideal companion for Rowohlt, who is increasingly transformed by alcohol into a huge, two-hundred-pound baby. He sat at the table with alcohol evaporating, in a manner of speaking, from every pore of his body, like some fiery-faced Moloch, albeit a contented, well-fed Moloch, while I regaled everyone with my jokes and anecdotes, at which even my dear wife laughed heartily, even though she had heard these gags at least a hundred times before. Rowohlt had by now reached the state in which his conscience sometimes directs him to make a contribution of his own to the general entertainment: he would sometimes ask the waiter to bring him a champagne glass, which he would then crunch up between his teeth, piece by piece, and eat the lot, leaving only the stem behind – to the horror of the ladies, who couldn’t get over the fact that he didn’t cut himself at all. I was present on one occasion, though, when Rowohlt met his match in this quasi-cannibalistic practice of glass-eating. He asked the waiter for a champagne glass, a quiet, placid man in the company did the same. Rowohlt ate his glass, the placid man did likewise. Rowohlt said contentedly: ‘There! That did me good!’ He folded his hands across his stomach, and looked around the table with an air of triumph. The placid man turned to him. He pointed to the bare stem of the glass that stood on the table in front of Rowohlt, and taunted him: ‘Aren’t you going to eat the stem, Mr Rowohlt? But that’s the best part!’ And with that he ate the stem himself, to gales of laughter from the assembled company. Rowohlt, however, cheated of his triumph, was furious, and he never forgave the placid man for this humiliation!

But appearances could be deceptive with Rowohlt: even though he sat there like a big, contented baby, with eyes half-closed as if he could barely see a thing, he was actually wide awake and right on the ball – scarily so, when it came to figures. Not realizing this, one time when I was strapped for cash I thought to pull a fast one on him in this baby state and negotiate a particularly favourable contract with him. I can still see us both sitting there, scribbling endless columns of figures on the menus. The contract was finally agreed in something of a boozy haze, and I was laughing up my sleeve at having finally put one over on this sharp businessman. The end result, of course, was that I was the one who’d been suckered – and how! Afterwards Rowohlt himself was so horrified by this contract that he voluntarily gave back most of what he had taken from me.

But on this particular evening there was no eating of glasses or transacting of business. The mood on this particular evening was one of satisfied contentment. We had done full justice to Schlichter’s wonderful chilled salads, his bouillabaisse, his beef stroganoff and his peerless mature Dutch cheese, and with the wine we had taken the odd sip of raspberry brandy to warm our stomachs. Now we were gazing at the little flames of the alcohol burners under our four individual coffee machines, heating up our Turkish coffee while we sat back and savoured another mouthful of wine from time to time. We had every reason to be pleased with ourselves and with what we had achieved. True, Little Man – What Now? had already peaked as an ‘international best-seller’;5like every international best-seller, it had been succeeded by something else that did even better, and I can’t remember now if it was Pearl Buck’s The Good Earth6 or Mitchell’s Gone With the Wind.7 In the meantime I had written Once We Had a Child, which the public didn’t like, although the author liked it very much, and now I was working on Jailbird.8 Maybe Jailbird wouldn’t be a new international best-seller either. But give it time – all in good time. It was the easiest thing in the world to create an international best-seller; you just had to really want it. For the present I was busy with other things that interested me very much: if it interested me one day to have an international best-seller, then I could easily manage that too.

Listening to these remarks, which were more drunken ramblings than seriously intended, Rowohlt nodded like a Buddha and seconded my words with an occasional ‘Quite so!’ or ‘You’re absolutely right, my friend.’ Our good lady wives were by now rather tired of hanging on the lips of the famous author and his famous publisher and imbibing words of pure wisdom, and were now talking in whispers at the other end of the table about housekeeping matters and bringing up children. The coffee, giving off its rich, intense aroma, was slowly starting to drip into the little cups positioned beneath the spouts . . . Into this supremely relaxed and contented scene there now burst an agitated waiter, to remind us that beyond our perfectly ordered private world there was a much larger outside world, where things were currently in a state of real turmoil. With the cry ‘The Reichstag is burning! The Reichstag is burning! The Communists have set fire to it!’ he dashed from room to room spreading the word. That certainly got the pair of us going. We leapt from our seats and exchanged a knowing glance. We shouted for a waiter. ‘Ganymede’, we cried to this disciple of Lucullus. ‘Fetch us a cab right now! We’re going to the Reichstag! We want to help Göring play with fire!’ Our dear wives blanched with horror. Göring had probably only been in the government for a few days,9 and the concentration camps had not yet entered the picture, but the reputation that preceded the gentlemen who had now seized control in Germany was not such that one could mistake them for gentle lambs meek and mild. I can still see it all in my mind’s eye – a confused, anxious, and yet ridiculous scene: the two of us seized with a veritable furor teutonicus, looking straight into each other’s eyes and shouting that we absolutely must go and play with fire ourselves; our wives, pale with terror, frantically trying to calm us down and get us out of this place, which was reputed to be Nazi-friendly; and a waiter standing at the door, hurriedly writing something on his pad – an extract from our manly declamations, or so we assumed from the amused applause. Eventually our wives succeeded in steering us out of the door, onto the street and into a cab, under the pretext, I assume, of going with us to see the burning Reichstag building. But we didn’t go there all together; first we took Rowohlt and his wife home, then our car headed east out of town, to the little village on the banks of the Spree10 where my wife and I were living at the time with our first son. Meanwhile my wife’s soothing words had calmed me down to the point where, when we drove past the Reichstag, I could look into the leaping flames of the burning dome – that sinister beacon at the start of the road that led to the Third Reich – without feeling any incendiary cravings of my own. It’s a good thing we had our wives with us that evening, otherwise our activities, and very possibly our lives too, would have come to an end on that January day in 1933, and this book would never have been written. We also heard nothing more about the head waiter and his furious scribblings, although his spectre haunted us for several anxious days: he was probably just making a quick note of the bills for his tables, since all the customers were then getting up to leave.

(24.IX.44.) This little episode says a great deal about the attitude with which many decent Germans contemplated the advent of Nazi rule. In our various journals – nationalist, democratic, social-democratic or even Communist – we had read quite a bit about the brutality with which these gentlemen liked to pursue their aims, and yet we thought: ‘It won’t be that bad! Now that they’re in power, they’ll soon see there is a big difference between drafting a Party manifesto and putting it into practice! They’ll tone it down a bit – as they all do. In fact, they’ll tone it down quite a lot!’ We still had absolutely no idea about the intractability of these people, their inhuman cruelty, which literally took corpses, and whole heaps of corpses, in its stride. Sometimes we had a wake-up call, as when we heard, for example, that a son of the Ullstein publishing family, when they came to arrest him,11 had asked if he could brush his teeth first; perhaps his tone had been a touch supercilious, because they promptly beat him half to death with rubber truncheons and dragged him away. People were being arrested left, right and centre, and a surprising number of these detainees were ‘shot while trying to escape’. But we kept on telling ourselves: ‘It doesn’t affect us. We are peace-loving citizens, we have never been politically active.’ We really were very stupid; precisely because we had not been politically active, i.e. had not joined the one true Party and did not do so now, we made ourselves highly suspect. It would have been so easy for us; it was in those months from January to March ’33 that the great rush to join the Party began, which earned the new Party members the scornful nickname ‘March Martyrs’. From March onwards the Party put a block on new membership, making it conditional upon careful vetting and scrutiny. For a long time the ‘March Martyrs’ were treated as second-class Party members; but the distinction became blurred with the passing years, and the March Martyrs for their part did all they could to demonstrate their loyalty and reliability. In fact, most of the Nazis who were later described as ‘150 per cent committed’ came from their ranks; in their zeal they sought to outdo the older Party members in the ruthlessness with which they enforced the Party line – as long as such measures didn’t affect them, of course. I shall shortly have occasion to speak about some of these fragrant flowers, whose acquaintance I was soon to make.

Strictly speaking, Rowohlt and I had every reason to be very careful indeed: we were both compromised, he more than I, but compromised nonetheless, and that was quite enough for the gentlemen in power, who didn’t bother with the finer nuances. They have always ruled by brute force, mainly by the brutal threat of naked physical violence, intimidating and enslaving first their own people, and then other nations. Even the relative subtlety of the iron fist in the velvet glove is too sophisticated for them – way beyond their powers of comprehension. All they ever do is threaten. Do this, or we’ll cut your head off! Don’t do that, or we’ll hang you by the neck! These utterly primitive ideas constituted the sum total of their political wisdom, from the first day until what will hopefully soon be the last.

So, Rowohlt and I were both compromised. He was known to be a ‘friend of the Jews’, and his publishing house had once been described by a Nazi newspaper as a ‘branch synagogue’. He had published the works of Emil Ludwig,12 whom the ‘militant journals’ persistently referred to as ‘Emil Ludwig Cohn’, even though he had never been called Cohn in his life. Rowohlt was also Tucholsky’s publisher, and in his magazine Die Weltbühne Tucholsky had conducted a dogged campaign to uncover the secret extra-curricular activities of the Reichswehr.13 Furthermore, Rowohlt had published Das Tagebuch,14 a weekly journal for economics and politics, which supported the League of Nations and the world economy, exposed the secret machinations of the ‘chimney barons’, and was generally opposed to all separatist or nationalist tendencies. He had also – the list of his crimes is truly shocking – published Knickerbocker,15 the American journalist who gripped his readers with his account of the ‘Red Trade Menace’ and the rise of Fascism in Europe, and who, on the personal orders of Mr Göring himself, had been denied a press pass to attend the opening session of the Reichstag under the aegis of the Nazis. Finally, Rowohlt had also published a book entitled Adolf Hitler Wilhelm III,16 which pointed out the remarkable similarities in character and temperament between these two men; he had published a little book called Kommt das Dritte Reich? [Is the Third Reich Coming?],17 which was less than enthusiastic about the prospect; and worst of all he had printed and published Geschichte des Nationalsozialismus [A History of National Socialism],18 in which all the contradictions, infamies and stupidities of this emerging political party were mercilessly laid bare. This book was subsequently sold under the counter for vast sums – officially, of course, it was immediately consigned to one of those book bonfires19 that burned all over Germany when the Nazis came to power, and on which pretty much everything with a Jewish-sounding name was burned indiscriminately. (The standard of literary education among the Nazi thugs was pretty dire, as was the standard of their education in general.) Add to that the fact that Rowohlt also had any number of Jewish literary authors on his list, and that his publishing house employed quite a few Jewish staff members. Enough already? More than enough, and then some! (One of these Jewish employees would later – officially at least – turn out to be his nemesis, but I shall come to that later.) Rowohlt had no interest in politics, and in mellow mood he liked to describe himself as a ‘lover of all forms of chaos’. He really was, and probably still is, someone who feels most energized in turbulent and chaotic times. The heyday of his publishing house was during the bad years at the end of the revolution and the beginning of the introduction of the Rentenmark.

I hardly need to relate my own catalogue of sins at such length, and in the pages that follow it will become clear how much I was loved, how fervently my work was encouraged and supported, and what joyous years I and my family experienced from 1933 onwards. I probably only need to mention that leading and ‘respected’ Nazi newspapers and journals described me as ‘the poster-boy goy for all the Jews on the Kurfürstendamm’, that they called me ‘the notorious pornographer’, and right up until the end disputed my right to live and write in Germany.

From the other side of the fence it has been much held against me that I didn’t draw the natural conclusions from these hostile attitudes towards me and leave Germany like the other émigrés. It’s not that I was short of generous offers. Back in the days when Czechoslovakia was being occupied, I was invited to escape the impending war and travel with my family to a nearby country, where a comfortable home, excellent working conditions and a carefree life awaited me, and where I would have been naturalized overnight. And once again, even after everything I’d been through since ’33, I said ‘No’, once again, obstructed in my work, constantly under attack, treated as a second-class citizen, menaced by the approaching shadow of a necessary war, I said ‘No’, and chose rather to expose myself, my wife and my children to all the dangers than to leave the country of my birth; for I am a German, I say it today with pride and sorrow still, I love Germany, I would not want to live and work anywhere else in the world except Germany. I probably couldn’t do it anywhere else. What kind of a German would I be if I had slunk away to a life of ease in my country’s hour of affliction and ignominy? For I love this nation, which has given, and will continue to give, imperishable sounds to the world. Here songs are sung as in no other country upon earth; here in Germany were heard strains that will never be heard again if this nation perishes! So true, so forbearing, so steadfast, this nation – and so easily led astray! Because it is so trusting – it believes every charlatan who happens along.

And I’ll say it here and not mince my words: it wasn’t the Germans who did the most to pave the way for National Socialism, it was the French and the British.20 Since 1918 there have been many governments who were more than willing to cooperate – but they were never given a chance. It was repeatedly forgotten that they were not only the executors of measures forcibly imposed by foreign countries, but also the representatives of an impoverished and starving people, whom they loved! It is those others who have thrust us into the abyss, into the hell in which we are now living!

So yes, I have stayed, and many others with me. We have given each other courage, and we have made something of ourselves in Germany; let it be said without arrogance, in all modesty indeed, that we have remained the salt of the earth, and not everything has lost its savour. It was inevitable, of course, that people in my neighbourhood would realize that I was a black sheep, nobody in my house has ever said ‘Heil Hitler!’, and in such matters the ears of people in Germany have become remarkably acute over the years. Many people have spoken to me very openly about their true feelings, and that has given me and them the strength to carry on and endure. We didn’t do anything so preposterous as to hatch conspiracies or plot coups, which is what people in other countries always expected of us, utterly failing to recognize the seriousness of our situation. We were not intent on committing suicide when our death would be of no use to anybody. But we were the salt of the earth – and if the salt has lost its savour, with what shall it be salted?

Although it doesn’t actually belong here, I will tell a little story at this point that happened to me in the first years after the Nazis came to power, and which will perhaps give some idea of how the atmosphere in my house immediately encouraged those of like mind to emerge from the silence they so anxiously maintained the rest of the time. One day a repair man from Berlin called on us to fix some appliance or other. He was a real Berliner, quick on the uptake, and he had immediately grasped what kind of house this was. At the table – we always eat together – he loosened up more and more, finally regaling us with the following delightful and instructive story, from which one can see that in Germany, even in the worst of times, there were still (and there always will be) plenty of upright and unwavering men in every walk of life. Anyway, this repair man told us the following story in his strong Berlin accent: ‘So the doorbell rang, and when I opened up there was one of the Chancellor’s tin-rattlers standing there with a list in his paw. “I’m from the WRO”,21 says the man, “and we can’t help noticing that you have never contributed to the great relief effort for the German nation. The Winter Relief Organization, that is . . .” And he reels off his spiel, and I let him rabbit on, and when he’s finished I say to him: “Look mate,” I say, “you can save your breath because you’re not getting anything out of me!”

“Well,” says he, “if you’re still not going to give anything even after I’ve paid you a personal visit, then I’ll have to put a circle after your name on my list of addresses, and that could have very unpleasant consequences for you.”

“Look mate,” I say again, “I don’t give a monkey’s what kind of geometric shapes you draw after my name, I’m still not going to give you anything!”

Now he tries a bit harder. “Look here,” he says, “don’t be like that, don’t get yourself into trouble when there’s no need! Just give me a fifty and I won’t put a circle on the list – job done!”

“You think?” says I. “But a fifty, that’s a whole loaf of bread, and a loaf of bread is a big thing for me: I’ve got five kids.”

“What!” says this fellow, all excited. “You’ve got five children? Then you’re a man after our Führer’s own heart!”

“Whatever,” says I, “but just so you know: we had all the children before your lot came to power!”

“You know what?” says he, “you’ll never make a good National Socialist as long as you live!”

“You’ve got it, mate!” I reply. “I won’t even make a bad National Socialist!”’

I must admit this little story made a lasting impression on me, and the line about not even making a bad Nazi proved very helpful to me in many of the situations I would find myself in during the times ahead.

If I ask myself today whether I did the right thing or the wrong thing by remaining in Germany, then I’d still have to say today: ‘I did the right thing.’ I truthfully did not stay, as some have claimed, because I didn’t want to lose my home and possessions or because I was a coward. If I’d gone abroad I could have earned more money, more easily, and would have lived a safer life. Here I have suffered all manner of trials and tribulations, I’ve spent many hours in the air-raid shelter in Berlin,22 watching the windows turn red, and often enough, to put it plainly, I’ve been scared witless. My property has been constantly at risk, for a year now they have refused to allocate paper for my books – and I am writing these lines in the shadow of the hangman’s noose in the asylum at Strelitz, where the chief prosecutor has kindly placed me as a ‘dangerous lunatic’, in September 1944. Every ten minutes or so a constable enters my cell, looks curiously at my scribblings, and asks me what I am writing. I say: ‘A children’s story’23 and carry on writing. I prefer not to think about what will happen to me if anyone reads these lines. But I have to write them. I sense that the war is coming to an end soon, and I want to write down my experiences before that happens: hundreds of others will be doing the same after the war. Better to do it now – even at the risk of my life. I’m living here with eighty-four men, most of them quite deranged, and nearly all of them convicted murderers, thieves or sex offenders. But even under these conditions I still say: ‘I was right to stay in Germany. I am a German, and I would rather perish with this unfortunate but blessed nation than enjoy a false happiness in some other country!’

Reverting now to Rowohlt and me and that time of innocence in January ’33: yes, we were badly compromised, and sometimes we admitted as much to ourselves. But then we kept on reassuring ourselves with the fatuous observation: ‘It won’t be that bad – at least, not for us.’ We fluctuated wildly between utter recklessness and wary caution. Rowohlt had just told his wife the latest joke about G., only to turn on her angrily because she had told the same joke to my wife. Did she want to ruin them all? Did she want to land them all in a concentration camp? Was she completely mad, had she taken leave of her senses?! And then the very same Rowohlt went and pulled the following stunt. His wife was actually by far the more cautious of the two, and since she knew very well that they were not exactly renowned in the neighbourhood as a model Nazi household, she took great care to greet everyone she met with the proper Hitler salute and the words ‘Heil Hitler!’ Trotting along beside her was her little daughter, who was probably four at the time24 and just called ‘Baby’, who raised her arm in greeting just like her mother.

But her dear father, Rowohlt, who was always full of bright ideas and loved to play tricks on his wife, took Baby aside and trained her and drilled her, so that the next time her mother was out on the street with her, dutifully greeting everyone with ‘Heil Hitler!’, Baby raised her left fist and yelled in her clear little voice: ‘Red Front! Blondi’s a runt!’ What tears and fits of despair the poor mother went through to get the child to unlearn this greeting, which really wasn’t exactly in step with the times! But Rowohlt, the overanxious and cautious one, just laughed; his enjoyment of this excellent joke far outweighed any fear of the very real danger. Giving the ‘Red Front’ salute meant being sent to a concentration camp at the very least – and probably much worse than that.

At other times Rowohlt would phone me in my little village, where the young postmistress, with too much time on her hands, was always very curious about the telephone calls of the ‘famous’ local author, and he would greet me with a full-throated: ‘Hello, my friend! Heil Hitler!’

‘What’s this, Rowohlt?’ I would ask. ‘Have you joined the Party now, or what?’

‘What are you on about!’ cried the incorrigible joker. ‘We’re all brown at the arse end!’

That was Rowohlt for you, and basically he never changed. And I was the same, perhaps not quite so active or inventive, and certainly not as witty; but in those days I developed a dangerous penchant for little anecdotes and jokes poking fun at the Nazis, I stored them up in my mind, so to speak, and shared them readily with others – though I was often rather careless in my choice of listeners, especially if the anecdotes were particularly good and I was bursting to tell. This was bound to end badly, and end badly it very soon did. But before I tell the story of my first serious clash with the Nazi regime, I need to say a little more about the circumstances in which we were living at the time. As already stated, the success of Little Man came and went very quickly, I had spent the money none too wisely, and when my wife called a halt to my extravagance we had a little money left, but not very much. To ensure that what little we had left would not drain away too quickly, we decided to move out to the country, far removed from the temptations of bars, dance halls and cabarets. After looking around for a while we found a villa on the banks of the Spree in the little village of Berkenbrück; we rented the upstairs rooms and decided to use this as a temporary base, living here while we looked for a place of our own to buy further out from the city. Everything about the place seemed to suit us down to the ground. The villa lay at the far end of the village, overlooking the forest, one of a small number of townhouses that had been built on the outskirts of what was basically a rural farming village. The garden facing the road, which had hardly any passing traffic, was on the level, while round the back it sloped steeply down to the river, which here flowed past in a straight line between engineered banks. There was an abundance of fruit trees, lots of outbuildings, and it all looked a touch neglected, on the brink of dilapidation. The reason for this was that our landlords were entirely without means. The husband, Mr Sponar, in his seventies, with a smooth, chiselled actor’s face and snow-white hair, always wore velvet jackets and little loose, flapping cravats, and fancied himself a bit of an artist. He certainly had an artist’s lack of business acumen. He had owned a small factory in Berlin, where they manufactured alabaster shells to his own designs in a range of attractive soft colours, intended for use as lampshades. At one time the factory had been doing very well, when these alabaster lampshades were all the rage, but then people’s taste turned to other kinds of lamps. Sponar had doggedly defied this shift in taste, continuing to produce his beloved alabaster shells to his own designs. He had sunk all his savings into this pointless protest, mortgaging his house on the Spree down to the last roof tile. And then the economic collapse had come, before alabaster lampshades were back in fashion again. When you heard the seventy-year-old talk about this, his dark eyes flamed beneath his white hair; he still believed in the enduring appeal of alabaster lampshades, as others believe in the second coming of the Messiah. ‘I shall live to see the day when everyone will be buying alabaster shades again!’ went up the cry. ‘This present fashion for parchment lampshades, paper lampshades even – what on earth is that? It shows a complete lack of taste. Firstly, an alabaster shade gives out a soft light that can be tinted to any colour you like, and secondly . . .’ And he would launch into a lengthy excursus on the advantages of the lamps made by him. Mrs Sponar, his espoused wife, had something of the dethroned queen about her, an air of Mary Queen of Scots in the hour before her execution. Her hair too was snowy-white, crowning a face that was white and almost wrinklefree, there was something Junoesque about her figure, and she had what one might call an ample bosom – which she knew how to carry off. It was not hard to tell who wore the trousers in that marriage. The retired artist obeyed the dethroned queen in all matters without question. I rather doubt if it had always been this way. This undoubtedly clever, or at least wily, woman would surely not have allowed her husband to ruin himself so foolishly while she stood idly by. I imagine he did it all behind her back, and only when she discovered the full extent of his business failure did she seize the reins of government. But it was too late. They had become impoverished – worse than that: they were on welfare. The rent that I paid them – and it was no small amount – all went to the mortgage lenders, who were happy to get a little interest at last on the money they had lent. In the meantime the Sponars were living off the meagre pension that the social services paid them during those lean years, which probably amounted to something like thirty marks a month – that’s for husband and wife together, of course! As the saying goes: not enough to live on, too much to die for. Things were made easier for them, of course, in that they were still living in ‘their’ own house and could feed themselves from ‘their’ own garden. In other times, needless to say, the mortgage lenders would have long since lost patience and forced them to put the house up for auction; but in order to prevent total chaos in the property market one of the previous governments had introduced something called ‘foreclosure protection’, which meant that a foreclosure could only be initiated if the borrower gave his consent, which of course happened only in very rare instances.

Such were our landlords, and such were the circumstances of their lives at the time, which they made no secret of. In general we got on very well with them; as tenants we were not the petty-minded type, and if something needed repairing I had it done at my expense, even though it was technically the landlord’s responsibility. The fact is that the Sponars were destitute. I even paid the old man a small monthly allowance, in return for which he pottered about a bit in my part of the garden, strength and health permitting. But we were more cautious in our dealings with the dethroned princess: she acted all condescending and friendly, but we never quite trusted her. Her big eyes often lit up with something like pain, and I sometimes thought that she hated us because we had what she had lost: property, a carefree life, happiness. The days passed and turned into weeks and months, and we felt more and more at home in our villa on the Spree. Our little boy cheered every tug boat that went past almost under our windows, belching thick black smoke and towing long lines of barges in the direction of Berlin. We went for long walks in the woods, and sometimes we forgot for hours on end that Berlin even existed, even as the Nazis there continued to strengthen their hold on power, banning other political parties and confiscating their property. I remember saying to my wife in outrage, when the Liebknecht House was taken over and changed into the Horst Wessel House with a lot of pomp and ceremony (as if they had won a huge victory or something): ‘It’s so brazen, the way they carry on! It’s just theft, pure and simple! But they get away with it precisely because they are so shameless about it, as if it’s the most natural thing in the world!’

But if we happened to be in Berlin and came across formations of brownshirts or stormtroopers marching through the streets with their standards, singing their brutish songs – one line of which I still remember clearly: ‘. . . the blade must run with Jewish blood!’ – then my wife and I would start to run and we would turn off at the next corner. An edict had been issued, stating that everyone on the street had to raise their arm and salute the standards when these parades went past. We were by no means the only ones who ran away rather than give a salute under duress. Little did we know at the time that our then four-year-old son25 would one day be wearing a brown shirt too, and in my own house to boot, and that one day I too would have to buy a Nazi flag and fly it on ‘festive days’. If we had had any notion of the sufferings that lay ahead, perhaps we would have changed our minds after all and packed our bags. And when we returned home to Berkenbrück we congratulated ourselves on our peaceful village existence. We looked at each other and said: ‘Thank God! The farmers out here in the country are not bothered about the Nazis! They till the soil and are happy just to be left in peace!’ What naive fools we were! Our eyes would soon be opened to the realities of Nazism in rural life!

Meanwhile we had grown to like our villa so much that we decided to stop looking for somewhere else and to stay where we were – but to become owners rather than tenants. That would not be possible without the consent of the Sponars. So we went to see them and made the following proposal: I would buy up the mortgages from the individual mortgage lenders, and he would agree to let the house be put up for compulsory auction. At the sale I would then acquire the house for the value of the mortgages, the property being so heavily mortgaged that there was no danger of anyone outbidding me. In return for his consent to the auction I would grant him and his wife a lifelong right of residence in the ground-floor apartment – admittedly half the size of what they had now – and in addition I would pay them both a monthly annuity that was twice as much as the pension they were getting from social services. In return, he would help out in the garden as far as his strength permitted.

I was offering the Sponars an incredibly good deal here. The protection against foreclosure would not last indefinitely; the house would come under the hammer one day, and he would lose the right of residence there, lose the garden, and not get a penny in compensation. So I was astonished when the couple seemed unsure about accepting my proposal. I pressed them, and eventually he came out with it. He felt that by agreeing to let the house be put up for auction he was placing himself entirely in my hands. Once the house had been sold at auction, he said, the Sponars would have no rights at all, and I could do with them whatever I wanted. It was easy to make promises – no offence intended – but keeping them in these uncertain times was even less certain . . . I said with a laugh that his concerns could very easily be laid to rest: all we needed to do was go and see a notary together and put our mutual obligations in writing. He promised to think it over for a day or two. I couldn’t understand it – I thought he should have been grateful to me, simple as that. What I was offering was a pure gift. But people are strange, and old people especially. But he came to me next morning – it always pays to sleep on things – and gave his consent. I suggested that we go straight to the notary and get it all down in writing, exactly as he wanted. But all of a sudden he wasn’t in such a hurry any more. He had a touch of bronchitis, he claimed. Besides, there was no great hurry, he said: he knew I was a man of my word, the end of this week or the beginning of the next would be soon enough. Which was fine by me. I was exhilarated by the prospect of owning a house of my own, when just a short time ago I had had nothing to my name. Thinking that everything was settled, I travelled to Berlin and went to one of the big banks to arrange the transfer of the prime mortgage. They were happy enough to give it to me, and were just pleased to be rid of this instrument that had hardly ever yielded any interest. Then I set about buying up five or six smaller mortgages with a value of a few thousand marks each, which Sponar had presumably taken out when he was really up against it, in order to keep his head above water from one month to the next and carry on making alabaster lampshades that nobody wanted to buy. Having sorted all this out, I sat at home feeling very pleased, and waited for my landlord to get over his mild attack of bronchitis so that he could come with me to the notary.

Now comes a strange interlude, not without deeper significance, on the eve of Easter, when we planned to organize an Easter egg treasure hunt for our little boy. On Maundy Thursday26 we had a visit from a Mr von Salomon,27 who worked at my publisher’s. Mr von Salomon was not Jewish, as one might assume from his name (and as some people did assume), but came from Rhineland aristocracy. Salomon was a Germanized form of the French ‘Salmon’. He had three brothers, and anything more different than these three brothers it would be hard to imagine. They perfectly exemplified the condition of the German nation: disunited and riven by conflict. One of the brothers was a respectable bank clerk,28 an upright citizen, who was only interested in his own advancement. The second was a committed Communist,29 and if one is to believe his brother, the one I knew (although one certainly shouldn’t believe everything he said!), this brother had been honoured by Stalin in person with a distinguished award. At all events, this Mr von Salomon was soon one of Germany’s ‘most wanted’ men, defying the Nazi terror regime as he travelled constantly back and forth between Paris and Moscow as a courier, wearing a hundred disguises, braving dangers of every kind, and stopping off regularly in Berlin too, where the brothers met up from time to time. The third Salomon brother was a big cheese on the staff of the later notorious Mr Röhm, with whom, however, he did not perish: on the contrary, he rose ever higher through the ranks. He had the – for me – unforgettable first name ‘Pfeffer’. Pfeffer von Salomon – now that’s what I call aristocracy! And my Salomon too, still young as he was, had already had a fairly chequered past. As a young lad he had fought with the Iron Division in the Baltic,30 then he had joined the Consul Organization,31 had taken part in the Ruhr resistance campaign, and finally had been involved somehow in the murder of Rathenau.32 For that he spent some time in prison, where the fiercely nationalist sympathies of the prison staff at the time meant that he was feted as something of a celebrity. He even made a habit of going into town with the prison governor for an evening in the pub, where he found an admiring audience among the bar-room regulars for the tales of his exploits, although it was not unknown for him to get so carried away in the heat of the moment that he mixed up other people’s exploits with his own – for example, telling anecdotes from the Battle of the Marne as if he had been there in person, whereas he couldn’t have been more than twelve or thirteen at the time. When he came out of prison he wrote a couple of books about his experiences; he wrote well and fluently, as long as he stuck to his own adventures. In one of these books, Die Geächteten [The Outcasts],33 he sought to glorify the murder of Rathenau, turning things round somewhat to present the murdered Rathenau as a better kind of man, but with a dark and sinister side to him, while the poor murderers were forced to go on the run in Germany, innocents hunted like wild game. Another book, called Die Stadt [The City],34 is something of a curiosity, a hefty volume, written and printed as a continuous stream of words without any chapter breaks, or even paragraphs, to enliven the tedious uniformity of the text, or give the reader’s eye a chance to rest and pause. Booksellers were quick to dub the book ‘the book with no returns’ – and they were right on both counts: no paragraph breaks, and the book failed to sell, much to the chagrin of my good friend Rowohlt. Mr von Salomon soon discovered, however, that the business of writing books requires a lot of hard work, and often brings in very little money. Like many people who have bright ideas and don’t care for hard work, but do like to live well, he went into films instead. That suited him very well, and when I last saw him on the Kurfürstendamm he had put on a lot of weight, and the acquaintance of a minor writer was clearly a thing of very little importance for a man who was constantly hobnobbing with the film stars of the day. But back then, when he visited me that Maundy Thursday, all this still lay in the future. At that time Mr von Salomon was as lean as a whippet, to which he bore a striking resemblance with his aristocratic, sharp-featured face. I don’t remember any more why he came to see me, he probably just wanted to tell me the latest jokes about Hitler and the Party: back then it was a sort of parlour game – people couldn’t spread the word fast enough! Von Salomon was a funny and talkative man, who knew everybody in the world of literature and art, and the hours passed quickly enough in his company. It would have been a bit wiser, perhaps, to have had this conversation not out in the hall, but in a room where we could have closed the door behind us: but which of us is wise all the time? At that time, certainly, we were anything but. And which of us can always keep in mind that someone downstairs only needs to leave a door ajar in order to hear every word that’s spoken upstairs? The acoustics of a house are unpredictable: sometimes you can hear everything, sometimes nothing at all, and on this Maundy Thursday afternoon someone damned well heard just a little too much!

Now comes interlude Number 2, again not without deeper significance, particularly for the study of the human character. By now it was Good Friday, my wife and I were walking in the garden, while our son tottered gamely along between us on his three-year-old legs. It was still mid-morning, the bell up in the village had just started to ring for the morning service, so it must have been shortly before ten o’clock. We were just admiring the crocuses and tulips and hyacinths that had pushed their way up through the withered leaves, their blooms a blaze of colour in the bright sunshine. We did our best to stop our son picking the flowers – with varying degrees of success.

And then the Sponars emerged from the house, prayer books in hand, ready to set off for church; she looked, more than ever, every inch the dethroned queen, while he, having exchanged the velvet jacket for a black frock coat, was the eternal artist, playing the part of a graveside mourner. They marched straight up to us and halted in front of us. ‘It is our custom’, said Mrs Sponar in that deep and slightly doleful voice of hers, ‘to take Holy Communion on Holy Friday.’ (This excess of holiness was already making me feel uncomfortable.) ‘It is also our custom’, Mrs Sponar went on, ‘before we take Holy Communion, to ask forgiveness of our friends and acquaintances and relatives for any evil that we might have done them in thought or deed, either knowingly or unknowingly. And so, Mr Fallada, Mrs Fallada, we ask your forgiveness – please forgive us!’ Tears of emotion actually welled up in their eyes, while we, my wife and I, felt so angry and embarrassed that we wanted the ground to swallow us up. ‘They can keep their private religious claptrap to themselves!’ I thought, thoroughly infuriated. ‘It’s all sanctimonious humbug! The queen never regrets anything, is without fault, and cannot ask for forgiveness, and he’s just an old fool! It’s sickening – why can’t they just leave us alone!’

But what can you do? We’re brought up to hide our true feelings and just put on a good face in these situations. I’m afraid my face wasn’t up to much as I assured them we had nothing to forgive them for, and as far as we were concerned they could take communion with a clear conscience. They thanked us again very emotionally, while the tears coursed down the old hypocrites’ faces. Had I known then what I suspected twenty-four hours or so later, and what I knew with absolute certainty some twelve days after that – that these two bastards had already shopped us to the Nazis even as they begged us for forgiveness, and that in return for money they had stored up trouble, illness and mortal danger for us – I think I would have strangled them there and then with my bare hands! But as it was, I just watched them walk out of the garden in their solemn black garb, prayer books in hand, and turned to my wife: ‘What do you make of that?’

‘It makes me sick!’ she burst out. ‘We could have done without their play-acting. Or did you believe a single word they said?’

‘Not a word’, I replied, and then we walked down through the garden to the Spree, where our little boy’s delight in the rippling waves and river barges soon made us forget all about the two old hypocrites.

(25.IX.44.) The next morning came, it was the Saturday before Easter, and mother was busy with cooking and baking. So father and son went out by themselves, down to the banks of the Spree again, walking side by side with Teddy in the middle. Teddy was a wonderful and indestructible creature; I’d bought him when we were still living in ‘straitened circumstances’ for the sum of 33 marks, much to the horror of my wife. Teddy stuck out his jolly red tongue, and he seemed to take as lively a pleasure in the sunny spring sky and the bustling river traffic as my boy did. For a while we were content just to stand there and watch, and then we started to play more actively, poking about in a little patch of reeds and disturbing some birds, which flew up, chirping indignantly. We’d parked Teddy on a molehill while we played. We were still rummaging about when suddenly there were two figures standing in front of us, wearing those brown shirts that I didn’t care to see even then, and the sight of which still unsettles me to this day. Each of the figures had a pistol in his hand, which was unmistakably pointed at me. ‘Uh-oh!’ I thought to myself. ‘Are you Fallada?’ one of them asked. Except that the speaker didn’t say ‘Fállada’ with the stress on the first syllable, which I prefer, because it sounds a bit like a triumphant blast on the trumpet; instead he pronounced it ‘Falláda’, which always sounds like someone who’s about to trip over and fall flat on his face. In a way he was right, because I was