9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Maisie Dobbs

- Sprache: Englisch

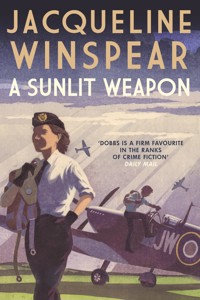

'Winspear pulls it off brilliantly' DAILY MAIL October 1942. Jo Hardy, an Air Transport Auxiliary ferry pilot, is delivering a Spitfire to Biggin Hill Aerodrome, when she has the terrifying experience of coming under fire from the ground. Returning to the area on foot to find out who was trying to take her down, she discovers an African American soldier bound and gagged in an old barn. When another ferry pilot crashes and dies in the same part of Kent, Jo is convinced there's a connection between all three events and she wants desperately to help the soldier now in the custody of American military police. Jo takes her suspicions to Maisie Dobbs and as the psychologist-investigator delves into the case, she discovers that the targeting of ferry pilots and the plight of the soldier are bound up with the visit to Britain by the First Lady of the United States, Eleanor Roosevelt. Maisie must work fast to uncover the link, to save the president's wife and a soldier caught in the crosshairs of those who would see them both dead. 'Fans and newcomers to the series will root for Dobbs' LOS ANGELES TIMES 'In A Sunlit Weapon, Maisie's pluck, intelligence and moral fortitude are on full display' WASHINGTON POST

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 538

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

5

A SUNLIT WEAPON

A Maisie Dobbs Novel

JACQUELINE WINSPEAR

In memory of Margaret Elizabeth Morell, née Callahan 1918–2012

Margaret, a first lieutenant with the American Army Nursing Corps, volunteered for overseas duty following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour in December 1941, and soon after shipped out to England on the RMS Queen Mary. Margaret was about to be deployed to the Pacific theatre when VJ Day was announced, and did not return home to the United States until 1946. She was my mother-in-law. Of her service to her country, Margaret told me, ‘They were the best days of my life.’

We are in a war and we need to fight it with all our ability and every weapon possible. Women pilots, in this particular case, are a weapon waiting to be used.

– Eleanor Roosevelt

(Eleanor Roosevelt wrote to the US aviation authorities after hearing about the service of women ferry pilots with the British Air Transport Auxiliary. They were among the women working in wartime roles she made a point of meeting during her 1942 visit to the UK.)

Oh! I have slipped the surly bonds of Earth

And danced the skies on laughter-silvered wings;

Sunward I’ve climbed, and joined the tumbling mirth

of sun-split clouds, – and done a hundred things

You have not dreamed of – wheeled and soared and swung

High in the sunlit silence. Hov’ring there,

I’ve chased the shouting wind along, and flung

My eager craft through footless halls of air …

– from ‘High Flight,’ by John Gillespie Magee

(John Gillespie Magee was an Anglo-American pilot with the Royal Canadian Air Force. He was killed in a mid-air collision while flying a Supermarine Spitfire over England in 1941. He was nineteen years of age.)

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

Somewhere over south eastern England Thursday, October 8th, 1942

Nick had told her about this feeling; a wild rush, a sensation of utter freedom that seemed to course through the veins with every twist and turn at the controls of a Spitfire. He’d described the way the Merlin engine would rumble away as he swooped down over harvests sunlit in summer and mist-drenched in the grip of autumn. Now Jo Hardy loved the Spit as much as Nick had – hardly surprising, as he’d always said the aircraft was a lady in the air. ‘It’s a woman’s kite, if ever there was one,’ he’d told her: compact in the cockpit, easy for a petite feminine frame to get in and get out. But Nick – her tall, wonderful Nick, the RAF officer who had swept her off her feet with his silly jokes and impish impressions of fellow officers – never got out. Nick never had a chance to push back the aircraft’s hood with scorched hands and escape the flames as his Spitfire crashed to earth.

So much had come to pass since that day – since she received the confirming message of his death from her commanding officer. Jo had no more tears to shed now. She had been a WAAF – a member of the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force – on duty in the ops room on her shift. Nick knew she was there, headphones clamped to her ears as she scanned the screen in front of her. She was tracking the exact position of the squadron when Nick seemed to lag behind; when, for no apparent reason, he began falling from the sky. She was staring at her radar screen as the other WAAFs turned to her, stunned. Then Nick’s voice came in loud and clear. ‘I’ve copped something. Don’t worry, I’ll land this thing.’ There was an easy laugh that calmed her, a few seconds’ worth of assurance that all would be well. ‘See you later, Josie.’ And then he was gone. The dot had vanished. Another pilot down – and there had not been a Messerschmitt in sight.

Jo had not wasted time. Grief was something to be indulged for just a brief moment, because for every tear that ran down her cheeks, there were thousands of bereaved souls shedding more, their hearts broken for dead husbands and lovers, for dead fathers and mothers, and for children killed during three years of war. Her mother had offered fleeting sympathy, and then counselled, ‘Well, you’ve just got to get on with it now, darling. Just get on with it.’ Ellen Hardy had considered her daughter’s fiancé ‘flighty’ – and wasn’t that an irony? thought Jo, that night as she pressed her face into her pillow and keened her loss. Now the man whose ring she kept in a pocket close to her heart was gone, and her mother was complaining about the means by which Jo had decided to just get on with it – by transferring to the Air Transport Auxiliary. She’d already learned to fly before the war, indulged by a father anxious to annoy his estranged wife by any means possible, and now Jo was in the air, ferrying fighters, bombers, and training aircraft from one air station to another. She had amassed more hours in the cockpit than Nick had under his belt on the day he died. Yesterday she was at the controls of a Blenheim, tomorrow it could be a Beaufighter or perhaps even a Lancaster, those four massive engines daring her to make a mess of her landing while a gaggle of engineers formed an audience on the ground. Those same men had been shocked when Diana, all five feet two of her, had climbed down from the cockpit of the Lanc she’d ferried to its destination, a bomber station in Northamptonshire. Just Diana, no seven-man crew. That bomber had been lined up for an expert landing by a woman on her own – a woman who had to put pillows on the seat to drive a motor car.

But today – today there had been a Spitfire on Jo’s chit. It was the second time she would be ferrying a kite she could take to four hundred miles per hour with ease – if only she were allowed such leeway. But really, who was to know? That first time it took only the usual half an hour with the instruction book, and she’d been up in the air determined to put the Spit through its paces before she landed – with no one around to catch her having some fun. Everyone wanted to fly the Supermarine Spitfire – that’s why the American aviatrices came over and joined the ATA even before Pearl Harbour brought thousands of GIs to British soil. Now there was an Argentinian among their number, a Czech, a few Canadians and a Polish girl too, the latter as fearless as her country’s fighter pilots who had taken off when the Nazis invaded their country. Those Poles had flown to Britain determined to have their revenge on the Luftwaffe.

Should she risk swooping under a bridge? She had the measure of the Spitfire now and felt like an old hand … so … well, why not? Last week when Jenny was delivering a Spit to Biggin Hill, she thought she’d execute a couple of barrel rolls before landing her charge – only to shock the RAF officer waiting on the tarmac, red with temper and at the ready to tear the pilot off a strip for indulging in risky airborne high jinks. There was no love lost between the RAF brass and the ATA. According to a story that had already become legend, the crusty officer was stunned into silence when he saw the aviator pull off ‘his’ helmet as Jenny clambered down to the ground, revealing long blond hair and a winning smile as she approached him, saluted, and said, ‘Good morning, sir. Apparently I’ve got to shift a Hurricane down to Hawkinge. Mind if I have a quick cuppa before I leave?’

Jo had ferried this route before, and though captivated by the fields and farms below as she crossed into Kent bound for Biggin Hill, she kept a keen eye around and above her. Ferry pilots had no ammunition on board, so if a lone-wolf Luftwaffe pilot came out of the clouds in his Messerschmitt, she’d have to move fast – evasive action was the only option to save her own life and a valuable aircraft. And that was her job, her remit – to deliver an aircraft in one piece, because God knows they couldn’t lose any more aeroplanes or pilots.

At last she saw the bridge – they all knew where it was, a railway bridge high enough and wide enough for a thrill. Ease up on the throttle, bring down the nose, level flight under the span and then open her up and climb fast on the other side. Jo felt the rush of adrenaline hammer through her body as she pulled up the Spitfire, the carburettor flooding the engine with fuel for sudden acceleration. She began to laugh. She hadn’t laughed in so long, it was as if shackles were beginning to fall away from her heart. Turning the Spitfire, Jo swooped in low over the fields. That’s when she heard it – a crack aft of the Spit, as if something had snapped, or she’d hit something – or something had blown or flown into the aircraft. She reduced speed, turned and swooped low again, just to make sure she could climb, relieved when she realised she wasn’t losing fuel nor was she on fire. Perhaps it was a bird, or just one of those sounds that seem to come out of nowhere to keep you on your toes – the gods of flight making sure you were paying attention.

Then she saw him. A man standing by the open door of a barn in the middle of a field, his firearm pointed skyward. She pulled up again and then came in low – but not too low – for another look. And he was firing once more, as if a mere bullet could bring her down, though she knew as well as anyone that a bullet could bring you down if it caught an aircraft in the wrong place.

Jo Hardy manoeuvred her ship once more to loop around the barn, just as another man ran from the open doors to grab the man with the weapon, still pointed skyward. Losing not a second, she identified her landmarks. There was the bridge, and there was a farmhouse. There was the road – and the railway line running close by. The corner of the field was at a fork in the road. Yes, she could find this place again, her mind a map and the coordinates memorised as if she’d pressed pins into paper. Someone had tried to shoot her down, and for once it wasn’t a German – and it wasn’t a crusty old RAF officer who thought women had no business flying aeroplanes and who used words and official reports as the weapon of choice. Someone had it in for the pilot of an aircraft flying low across the skies over the Garden of England.

A road, somewhere in Kent, England

Sunday, October 11th

Consulting the map spread across her lap, Jo Hardy sat alongside her friend Diana ‘Dizzy’ Marshall, who was perched on the pillow that allowed her to see over the steering wheel from the driver’s seat of her mother’s Riley Nine motor car.

‘I hope this isn’t too far, Jo, I’ve barely enough petrol to get home, and I’d like to have a bit in the tank so we can drive down to the White Hart later. There’s that dishy pilot officer I have my eye on. Thank goodness we’ve another day off tomorrow. We can languish at the house before driving back to Hamble for our next duty. I’ve been flying for three weeks straight, so I need a long lie-in.’

‘Hmm, yes,’ said Jo, staring out of the passenger window. ‘Look! Here we are, Dizzy! Yes, turn here. This is the fork in the road. You can park over there, on the verge.’

‘Righty-o,’ said Diana, turning the steering wheel.

Jo folded the map as Diana pulled onto the grass verge and turned off the engine. ‘It’s across that field.’

‘And how do we know there’s not a nutter in there ready to hold a gun to your head?’

Jo rested her hand on the door handle, then stopped. ‘You’re right, Dizzy. Though seeing as it was a few days ago that a joker started taking potshots at my Spit, I’m sure whoever it was is likely to have moved on. Anyway, you stay here, and if I’m not back in about twenty minutes, then raise the alarm.’ She looked at her wristwatch. ‘Five minutes to get over there, five minutes back, and ten minutes in the barn, at the most.’

‘All right. I’ll stay here. Twenty minutes, at the outside. I’ll read the newspaper to keep my mind off you and also work out how I am supposed to raise an alarm in an emergency when we’re in the middle of nowhere.’

Jo laughed, picked up her knapsack and stepped out of the motor car, turning to her friend before she slammed the passenger door. ‘I think you should lock the doors, old girl, just in case.’

‘Good idea. And when I see you running across the field again, I’ll have the engine purring, ready for a quick getaway!’

‘Very funny!’

Except I wasn’t actually joking, thought Diana, as she watched Jo Hardy cross the narrow country road, clamber over a five-bar gate and set off across the field.

Jo could see the barn in the distance. She’d circle round, she thought, to make sure there was no motor car outside, or anything indicating danger inside. Approaching the barn, she slowed her pace and tried not to make squelching sounds in the mud as she lifted each booted foot and put it in front of the other. She stopped to survey the landscape; a blue-grey afternoon mist hung listless over autumn fields left barren after the harvest. The sun was just a circular outline in the sky, as if a penny were being held aloft behind gauzy cloud cover. She lingered at the rear of the barn and put her ear to the wood. Nothing. Creeping along towards the corner, she held her breath and peered around. Again, nothing. No sounds, no sign of human presence.

She exhaled. ‘Right, Jo Hardy – galvanise yourself,’ she whispered. ‘Someone tried to take you down, so it’s time to see if you can find out who and why.’

Jo shimmied along the side of the barn towards double doors that were old, heavy and moss-covered, with rusty hinges. She took a quick glance at the bolt, which appeared to have been left open, though when she tried to pull back the left door and then the right, they refused to budge. An overnight storm and the shuffling of cattle coming close to a food source had kicked up mud against the base of the doors, rendering them almost impossible to move.

‘Didn’t think I’d need a shovel,’ Jo whispered to herself. She shivered, an unaccustomed feeling of vulnerability leaching into her bones. She gave the left door one last pull. ‘Blast!’ The word came out louder than she intended. The last thing she wanted was someone with a cosh to come up behind her.

She was about to turn around and run as fast as her legs would carry her towards the five-bar gate and Diana in the motor car when she heard a whimper. She stopped, listened again. Another whimper, though now it seemed more like a moan. Was it a trap? She made her way along the rear of the barn until she was sure that what she had heard wasn’t just a breeze skimming across the roof. She swallowed hard. Diana would be waiting, watching the minutes pass.

‘Is anyone in there?’

This time the sound was more akin to a wail – the wail of someone who could not scream.

‘Oh God. Oh dear—’ Jo looked down at the base of the barn, at the worn and rotting wooden boards, soaked through and coated with a good century’s worth of mould.

‘Right—’ She began tearing at the planks, surprised when the first came away with ease. Then the second. She glanced towards the heavens. ‘Nick, if you’re up there, help me or tell me I’ve lost my marbles and I should run like mad.’

No voice came out of the ether with a ghostly warning for Jo Hardy, so she pulled the next board and the next, the sodden wood giving way to a strength she always knew was inside her, but she’d never had to use. Soon there was enough of a hole at the back of the barn to crawl through.

Light from a fallen roof beam illuminated bales of hay and the remains of a fire on the ground. As she knelt down by the ash and blackened wood, Jo wondered what kind of fool would light a fire in an old barn. Then the moaning started again. She felt sick as she came to her feet. The sound was coming from behind the bales. Now she could hear her own heartbeat, as if it were swishing through her ears. She continued to approach the source of the noise with caution, craning her neck without entering the space behind the bales – she had to be ready to get out, and fast.

‘Good Lord!’

The man on the floor was bound hand and foot, with a scarf tied tight around his mouth and a blindfold across his eyes. He whimpered, appearing at once terrified and grateful.

‘All right, don’t worry, I’ll get you out of here.’ Jo fell to her knees, and began to work the knots on the blindfold. ‘Blast!’ She reached into her knapsack and pulled out a penknife, which made a snapping sound as she opened the blade. The man flinched. ‘I’m not going to kill you, just hold on, and I’ll get you out, and then we have to move like lightning, because whoever did this to you might be back soon.’

Diana fidgeted and checked her watch again. Fifteen minutes gone and five remaining – and they were ticking away fast. She drew down the window to clear condensation forming against the glass, and looked across the field, her brow furrowed. That was when she heard another motor car approaching. She closed the window and ducked down, only to hear the vehicle slow, but not quite stop, before continuing on. She sat up as the motor car turned the corner ahead.

‘Bloody hell – he’s going to the barn. Oh for heaven’s sake hurry up, Jo! Hurry-hurry-hurry, you lunatic woman!’

Diana fought the urge to leave the Riley, ready to yell out a warning across the field, when she saw two figures running towards the gate, one holding onto the other. She started the engine, feeling her stomach lurch as her hands began to shake. She would rather be taking off in a new aircraft than sitting here in the driver’s seat of her mother’s motor car. She revved the engine, watching as Jo climbed over the gate – but the man faltered, slipping back, before trying to gain purchase again.

Holding her hand to her mouth as she watched, Diana saw Jo lean over the gate in an effort to help the man by taking his arm. Then, as if frustrated by the loss of momentum, Jo grabbed the man by his collar and half dragged him over the gate. Pulling his left arm around her shoulder and with her right arm around his waist, she supported him as they staggered across the road. It was clear he had lost all strength in his legs. Diana leapt from her seat to open the rear passenger door.

‘Let’s get out of here, Dizzy, and fast,’ said Jo, bundling the man into the Riley and slamming the door.

‘Right,’ replied Diana, taking the driver’s seat once again and glancing at their passenger in her rear-view mirror while Jo took her place and slammed the door. ‘And then when I’ve been as sick as a dog all over mother’s pride and joy, you can tell me where that poor man came from – and what we should do with an American soldier. I wonder if he’s a deserter.’

‘I ain’t no deserter, ma’am. And I saw them take my friend Charlie and I heard them say they were going to kill him, and I reckon they meant to do it.’ He gasped back tears. ‘Charlie ain’t like me. No, ma’am – he’s a white soldier. I pray they don’t think it was me who did wrong.’

Diana’s fingers became blue on the steering wheel, so tight was her grip. She leaned forward as if to make the Riley go even faster, and was about to speak when Jo turned back to the man.

‘Whoever “they” are, I’m pretty sure they tried to kill me too – so I will vouch for you.’

‘Won’t do no good, ma’am. Won’t do no good at all.’ He began to weep. ‘And he was my friend.’

The tears running down the man’s face persuaded Diana that the American Jo had just dragged weak with fear from a barn in Kent probably had a better idea of the fate awaiting him, despite any vouching on her friend’s part.

CHAPTER ONE

‘So, what happened to the poor man after you handed him over?’

The young woman, First Officer Erica Langley, was wearing the navy-blue-and-gold uniform of the Air Transport Auxiliary, as were her three companions. They were awaiting their instruction chits for the day, surrounded by their fellow service pilots chatting in clusters. Some might be flying three or four different aircraft, one after the other, from a bomber to a fighter or a training aircraft, perhaps direct from the factory, or returning the aeroplane to an engineering unit for repair.

Jo Hardy sipped from her mug of hot, strong tea and winced. ‘Ugh.’ She shuddered before continuing her story.

‘Well, the MPs at Biggin Hill got onto the Yanks, and that was it – it wasn’t long before a Jeep came whizzing along and picked him up.’

‘He’ll be lucky to get away with his life, make no mistake,’ said Elaine Otterburn, a Canadian aviatrix who had ferried a bomber into Britain, another workhorse for the RAF. Otterburn and her co-pilot had flown via Gander in Newfoundland and Shannon in Ireland.

Jo and the two British pilots looked across at the Canadian, who had an air of assured maturity, and was known to harbour a certain disregard for the rules. They all knew Elaine Otterburn, who would remain in Britain until she and her Canadian co-pilot had orders to join a return flight across the Atlantic because there was another bomber to fly to Britain following manufacture at a Canadian factory. The aviatrices were a little in awe of Otterburn, not least because she was an excellent pilot, well versed in what they called ‘airmanship.’ Not everyone would want to bring a bomber across the Atlantic, or put up with the indignity of having to wear – of all things – a nappy! Elaine had once suggested that it was all very well having a bomb bay, but why hadn’t some bright spark aircraft engineer thought of a lavatory?

‘What do you mean?’ asked Jo, taking up the conversation. ‘We know the Yanks have an attitude towards the colours mixing, but surely—’

‘They still go in for lynching, down there in America,’ said Otterburn. ‘Didn’t you know the Americans asked Churchill to institute segregation in Britain before they sent over troops? Old Winnie isn’t without his prejudices – we all know that – but there’s regiments from across the bloody Empire here, to say nothing of civilians, so how could the old boy have agreed to dividing the country by colour?’ She shook her head and drew from a cigarette. ‘Bloody stupid, if you ask me. All the same, remember this – what the Yanks do on their bases is their business. It’s pretty much seen as US soil on British land.’

‘Blimey,’ said Diana. ‘So the man Jo found in that barn will get sent back to the USA? He said his pal might be dead, yet as far as we know, no one has found a body.’

‘As far as we know,’ said Jo. ‘That pretty much sums it up. But let’s face it, no one’s going to let us in on the outcome just because we found the soldier.’ She looked at the clock and came to her feet. ‘Better not drink any more of this, otherwise I’ll be the one needing a nappy for a short run across England!’ She set her mug on the table and turned to the Canadian. ‘Elaine, I’m fairly determined to find out what happened to that man, not only because I’m pretty sure I saved his life – you should have seen the state he was in when I found him – but I saw his fear too. And remember why I was lurking around that barn in the first place – a man on the ground outside the barn had taken a potshot at my Spit, and at the time I was low enough for it to cause a bit of damage. Not that I can admit my fun and games, because I shouldn’t have been skylarking around in the first place.’

‘We’ve all done it,’ said Erica Langley.

‘Jo, don’t be stupid – this is a job for the police,’ said Diana. ‘Just let them look into it. Drop the whole thing.’

‘Dizzy, my problem is that having looked into his eyes, I don’t think I can just drop the whole thing. I felt awful for that poor soldier. I’ve thought about going back to the barn and poking around a bit more; see if I can find anything to support his story. Perhaps even talk to the farmer. I heard from Gillian, who took a Spit to Biggin Hill yesterday, that the word over there is that some American military police had a look around the barn, and it was decided the man – his name is Private Matthias Crittenden – could have done everything himself. Apparently, there’s a sort of knot that goes from loose to tight with just the flick of a wrist. If you’ve got everything else in place, it’s the last thing you do if you want it to look as if someone else tied you up. Magicians do it all the time, apparently. Frankly, he didn’t look the sort to have a go at something like that, and with that cotton shoved in his mouth, every time he tried to speak it made him choke. Anyway, from what I saw of the military police when they came to collect the soldier from Biggin Hill – they turned up driving one of those upholstered roller skates they call a Jeep as if they were in a chariot – it struck me they might be fast to make a judgment about the missing soldier and who was responsible. But that’s just my opinion.’

‘I couldn’t believe they asked us if Private Crittenden had attacked us. I mean, the poor man could hardly stay on his feet, let alone get the better of anyone!’ Diana shrugged.

‘Hello – look who’s on her way.’ Elaine Otterburn pointed to a woman in uniform making her way towards the mess. The officer seemed tired, circles under her eyes testament to the constant pressure of scheduling ATA pilots to deliver multiple aircraft, and to getting those pilots into position to do their job. ‘Here come our marching orders,’ she added.

‘Ladies, it’s a nice day for flying!’ exclaimed the officer as she crossed the room, handing out the chits informing each pilot of their instructions for the hours ahead.

‘Righty-o, First Officers Otterburn and Hardy, here you go. You’re taking a couple of Hurricanes to Hawkinge – the Anson air taxi is outside now to fly you over to collect them from maintenance, so jump to it because the pilot wants to get in the air and back here again for another lot. Marshall, lovely job for you – a Wellington to Hendon and a rare chance to impress the lads on the ground – the Anson taking you is coming up behind number fifteen hundred. And last but never least, Langley, it’s your lucky day – a Spit from the factory to Biggin Hill. There’s a motor car ready to take you over to Trowbridge to pick up your kite – you’ll probably be back before anyone else, but remember, no trying to see just how fast you can take her, no victory rolls, and don’t go under that bloody bridge, whatever you do. Make sure you bring her in for a nice, smooth landing, and don’t show us all up in front of the RAF.’

‘Ha! I’ve got the winning ticket, ladies!’ said Erica, slipping the chit into the pocket of her Sidcot suit. ‘Nice day for flying indeed.’

* * *

‘Billy, sit down, please. You’re only getting yourself into a lather.’

Maisie Dobbs, psychologist and investigator, looked across the room towards her assistant, Billy Beale, who was pacing in front of the floor-to-ceiling window looking out over Fitzroy Square. ‘I know MacFarlane said he would be here by half past ten, and he’s rarely late, but perhaps he’s just been held up.’ She glanced sideways at her secretary, Sandra, who shook her head. Maisie nodded and pressed on, taking a deep breath to remain settled on behalf of the less than calm Billy Beale. ‘Well, until he gets here, I’m going to my desk to clear a few things that came in from last week.’

Billy Beale said nothing as he continued pacing, pausing only to stare out the window towards the square. His features were drawn, his once wheaten-blond hair now grey. His jacket seemed to hang on a frame that had always been slender, but now revealed a weight loss that could only have come from one quarter – a profound state of worry.

Sandra raised an eyebrow. ‘Here you are, miss – the ledger from last month. There’s a couple of overdue bills in there. I think I should send a second letter.’

‘Right you are, Sandra,’ said Maisie. ‘I’ll have a quick look first, just to make sure we’re not nagging people who have lost their homes, or who are grieving.’

‘He’s here!’ Billy shouted, turning from the window and all but sprinting to the door.

‘Billy—’

‘Miss, I’ve got to go down and let him in.’

‘I know … but I want you to remember this, Billy. Although Robbie MacFarlane has a lot of information at his fingertips, he doesn’t know everything, and anything he knows is always subject to an element of doubt.’

Maisie saw Billy’s face crease as he left the room, his footfall heavy while descending the staircase to the building entrance, ready to let in the man who might give his family hope, who might tell him his son – the soldier they still called ‘young Billy’ – was alive.

‘I hate to say it, but not having any news at all is worse than getting a telegram with bad news,’ said Sandra, placing a sheet of paper in her typewriter. ‘Billy’s limp is more evident than it’s been in a long while, and I’m amazed Mrs Beale is holding up, especially with the other one an engineer on bombers.’

Maisie nodded, moving closer to Sandra’s desk. She kept her voice low. ‘Doreen’s had a lot on her plate over the years, and though I feared for her when news of the fall of Singapore came through, I have seen her resolve become stronger – plus she has Margaret Rose to consider. Billy’s love of his family will keep him on his feet. And so will we.’ She looked up, turning to greet their guest as he appeared in the doorway.

‘Maisie – good morning.’ Robert MacFarlane held out his hand to Maisie, the slight shake of his head signalling a warning. He nodded towards Sandra, who had come to her feet.

‘I was just about to make a pot of coffee,’ Sandra said. ‘We still have some from Miss Dobbs’ stash. Would you like a cup?’

MacFarlane turned to Maisie. ‘Is it the good stuff old Blanche liked, from that place in Tunbridge Wells?’

‘Ground Santos beans – Maurice’s favourite,’ said Maisie. ‘I managed to buy some a little while ago, but it’s remained fairly good in the tin. We only use it when our most esteemed associates visit.’

‘Count me in, then. If I’m not esteemed, who is?’ He pointed to Maisie’s office. ‘Let’s get on with it, shall we?’

With Billy and MacFarlane in her private office, Maisie closed the accordion doors, taking a seat alongside Billy to face MacFarlane, who clasped his hands atop the long table set perpendicular to Maisie’s oak desk. It was the table upon which a length of paper would be pinned in the midst of an investigation, where Maisie would begin to draw her ‘case map,’ a record of everything discovered in the course of their work.

‘Tell me, Mac. Just tell me straight,’ said Billy.

Maisie registered their guest’s barely raised eyebrow – Billy had only ever referred to Robert MacFarlane respectfully as ‘Mr MacFarlane’ or ‘Sir.’

‘Here’s what we have, Billy – it’s precious little, I’m afraid. And let me tell you, it’s more than most in your position would be privy to and must be received with care. The Japs are being … are being … obstructive with regard to the Red Cross obtaining information on our boys caught in Singapore, but we have some intelligence coming in, and of course we’ve matched it to any scraps discovered by the Red Cross.’

‘What about our son?’

‘As far as we know, the news is fair. We know he is still alive, but he was transferred from Changi Prison – which was where many British, Australians and Canadians have been held – and now he’s on his way to Burma.’

‘What?’

‘The Japs don’t just let the men sit there starving in prisoner-of war-camps – they put them to work. I’ll be honest with you, there have been tremendous losses – torture, starvation, dysentery, malaria – but your Billy is still alive.’

Billy leaned across the table towards MacFarlane. ‘Can you get him – and the others – out?’

‘No. No, we can’t.’

Billy placed his hands on either side of his head, as if the information imparted by MacFarlane was too much for his imagination to bear.

‘What will happen to him? What will happen to my boy?’

‘Billy, your boy is a man now, and a very strong man into the bargain. He came through Dunkirk, and there’s others who were with him then and who are with him now. There’s strength in those connections among the men.’ MacFarlane pressed his lips together and looked down at his hands before bringing his attention back to Billy Beale. ‘I’ll wager your son will come through. As long as he understands the best thing to do with the enemy in this situation is to keep your head down, look after yourself and your mates, and do what you’re told.’

Billy shook his head. ‘My boy has always had a quick tongue. I told him when he was a nipper that he’d have to wind his neck in or someone would chop it off for him.’

Maisie had been silent throughout the exchange, but turned to her assistant and rested her hand on his arm. ‘Billy, you understand your son better than anyone, but Robbie is right – he’s a man now. He’s not stupid, he learned his lessons, and as Robbie said, he’s come through Dunkirk, so he will come through this. Now you have to do your bit. Keep your family strong, because he’s going to need you all.’

Billy scraped back his chair and walked to the window, hands in his pockets. Then he turned to MacFarlane.

‘Thank you, Mr MacFarlane. Thank you, sir, for finding out about my son and for coming here. I’m grateful. Now if we could only get Bobby out of that bloody Lancaster bomber without him having to go down in it, then we’ll all be there for Billy when he comes home.’

MacFarlane took a deep breath. ‘There’s thousands out there with the same bone to gnaw away at, Bill – thousands of mums and dads, sweethearts and boys and girls. Anyway – I’ve to get on.’ He glanced at Maisie and motioned towards the door, stopping to shake hands with Billy and once again nod towards Sandra, who had only just returned with four cups of coffee.

‘Any chance of taking it with me, hen?’

‘Hold on, I’ll pour it into a mug,’ said Sandra. ‘That might be easier for you.’

Maisie followed MacFarlane – now holding a mug of steaming, aromatic coffee – down the stairs to the front entrance. A black motor car was parked on the flagstones outside, waiting for MacFarlane.

‘I’m sorry there wasn’t better news, Maisie,’ MacFarlane said, before taking a sip of coffee. ‘Oh, that’s lovely.’ He took another sip. ‘Lass, I don’t need to tell you that it’s been a bloody disaster since the Japanese moved into Singapore.’

Maisie nodded. ‘It wouldn’t be so bad if Billy hadn’t clung to the idea that his son was safe in a jammy posting, doing a bit of square bashing and drinking fruity cocktails.’

MacFarlane shook his head. ‘No one’s having fun in this war, Maisie – well, perhaps a few flyboys when they’re on the ground, and then they’re lucky if they come back again after they’ve taken off. Pity his other lad was determined to get into bloody bombers, though I understand he’s a clever engineer.’ He raised his forefinger to his driver as he held the mug to his lips with the other hand. One more minute. ‘Something else we found out. Young William Beale put his name on his attestation papers as “Will”. I wondered about that, so I did a bit of nosing around, found an old mate of his who was medically unfit after Dunkirk, and he said it was the son’s way of being his own man – he was fed up with being “young Billy” or being called “a chip off the old block.” Mind you, you’d know more about that sort of thing than me, wouldn’t you?’

Maisie opened her mouth to speak, but MacFarlane went on.

‘Anyway, from everything we know, it will be a bloody miracle if the lad comes home again.’ He passed her the mug. ‘Mind taking this for me, hen? Lovely drop of coffee.’

Jo Hardy maintained level flight on the port side aft of Elaine Otterburn. If she were honest, she had always kept the Canadian at arm’s length in the mess and she found it difficult to converse with her, their exchanges lacking the ease and banter she enjoyed with her fellow pilots. Yes, she’d heard the Otterburn name; Elaine clearly came from privileged stock, but so did most of the women in the ATA – how else could you afford to fly before the war, unless you had money to throw into thin air? But there was talk that Elaine had already made her mark as an aviatrix, before the war evacuating an important person out of Munich. It was all a bit hush- hush, so Jo thought it might be best not to know any more than that. Elaine had a son too, a boy now in Canada with her mother, sent over there for his own safety.

Jo kept her thoughts under control as she approached Hawkinge, landing seconds after witnessing the Canadian demonstrate a perfect wheels-down. She brought the Hurricane to a halt alongside Elaine, who gave her a thumbs-up from the cockpit, and as if her hand were clutching a mug, she made the time-honoured sign that it could be time for a cuppa, if not quite the hour for something stronger.

Elaine and Jo walked towards the office where they would present their chits for signature by an officer, proof that the aircraft had been delivered and at what time. They talked about the cloud coming in, the fact that they both quite liked a Hurricane and how long it might be before each had another short leave. Running their fingers through hair flattened by their leather flying helmets, they were laughing as they entered the office – straight into a wall of silence. No jocular banter greeted them, no ‘all-in-good-heart’ critical commentary on their landings from RAF men. Just a poker-faced squadron leader and a pale WAAF clerk.

‘What is it?’ asked Jo.

‘You two look like you’ve just seen Goebbels landing with the Führer,’ added Elaine.

‘Hardy, Otterburn. I’ve had your superiors on the blower, and I have some terribly bad news, I’m afraid. Bad for you and for us. I believe you were both with First Officer Erica Langley this morning.’

‘Erica? What about her?’ demanded Jo.

‘What’s the matter?’ asked Elaine, whose pallor now resembled that of the WAAF clerk.

The squadron leader turned to the clerk, not bothering to hide his disdain. ‘I cannot abide bloody emotional women – shouldn’t be allowed up in an aeroplane in the first place. You can deal with it.’ Having delivered his opinion, he marched to the door, slamming it on the way out.

The WAAF clerk cleared her throat. ‘First Officer Langley came down in farmland not terribly far from Biggin Hill. Perfect weather, no enemy aircraft in the area. It’s been speculated that she was—’

‘Being reckless?’ snapped Elaine Otterburn. ‘Is that it? So what if she was? For God’s sake, we’ve all done it. But we’re not bloody amateurs. We know what we’re doing, and most of us have far more hours in different kinds of aircraft than your flyboys. She’s come down on a good day in the air – is she all right? In hospital?’

‘Look, we weren’t born yesterday,’ said Jo, her temper salted by Elaine’s. ‘You can tell us what’s what, and you don’t see either of us bawling because one of our number had to land in a field, do you? I mean, it wouldn’t be the first time – there’s not a failsafe aircraft in the sky.’ Despite her indignation, she was already feeling a sense of dread in her gut.

‘Don’t have a go at me, for heaven’s sake! I’m only the bearer of bad news,’ said the clerk. ‘We only just heard it anyway, and we’re being good enough to let you know. Biggin Hill has jurisdiction, and according to the report, there’s nothing to indicate anything but pilot error. Langley was killed in an instant, and the Spit is – well, that’s another one off the books. Another one we needed up there instead of in bits across a field.’ She picked up a folder, clutched it to her chest and left the room, her eyes reddened by unshed tears.

‘I don’t believe it!’ said Jo Hardy, on the train to London. The women were back in their distinctive navy-blue-and-gold uniforms of tailored jacket, trousers and caps, their warm Sidcot suits rolled up and stashed in canvas kit bags. ‘I wish I knew what to do, because I can’t help feeling Erica could have been brought down by the same bloke on the ground with a gun. And then there’s the poor man I rescued from the barn. He seemed absolutely sure he’d be under suspicion for having something to do with his friend’s disappearance. I reckon he must know something about the man with the gun – even if he was blindfolded, he must have heard something.’

‘Jo, we have no idea what happened to Erica. And it’s a long shot that your man in the barn knows anything.’ Elaine paused. ‘Sorry, I didn’t mean that to come out like a bad pun,’ she added, lighting a cigarette. They sat in silence for a couple of minutes before she spoke again. ‘But I do have an idea for you – because, frankly, you’re a pilot, not some sort of sleuth.’

‘Go on,’ said Jo, her voice becoming testy. ‘I’m all ears.’

‘You should talk to a woman named Maisie Dobbs.’

‘Oh dear, she sounds like a parlourmaid.’

‘Don’t be so bloody stuck-up, Hardy – you Brits are all the bloody same.’ Elaine blew smoke out the open window, and shook her head. ‘I learned “bloody” at boarding school in Sussex. No wonder I was kicked out.’

Jo sighed. ‘Sorry – we’re both a bit wound up. Go on, Elaine, please continue. Clearly I’m out of my depth, and all I have is a hunch.’

‘Just as well, because Maisie Dobbs is the only person I can think of who might trust your hunch.’

‘I said I’m sorry! Now then, tell me who she is.’

‘She’s a psychologist and a sort of investigator. She’s worked with Scotland Yard – they ask for her assistance, not the other way around – and I have it on authority, though I am not supposed to know this, that she is also … also associated with the secret service.’

‘And how do you know her?’

‘It’s a long story, but – oh, Lord, here goes.’ Elaine drew from her cigarette again. ‘It was my fault that her first husband was killed. Then to add to the deficit in my moral account, a few years later she kindly saved my life in Munich, before the war. It was an act of extreme forgiveness and resulted in me taking responsibility for my son, which was long overdue. I ended up meeting my husband through her. He’s British, an engineer back home in Canada now – war work – though when we met he was assisting one of the men I brought out of Munich, one of those clever boffins. That’s all I can say about it.’ She came to her feet, threw the remains of her cigarette out of the window and closed it before taking her seat again. ‘Maisie Dobbs should have been the second passenger, but gave up her seat for someone else, a man she claimed needed it more than her – he was a Jew, and she said he wouldn’t stand a chance if he remained in Germany. Anyway, I suppose you could say she forgave me my trespasses – even invited me to Sunday dinner a few times, along with a motley assortment of other people. Someone told me that hosting Sunday dinner was her way of getting out of her own shell.’ She sighed. ‘If you ask me, she was trying to get out of her own private hell.’

‘What happened to her?’

‘The short of it is that she ended up marrying the American who saved her life after she’d packed me off in a Messerschmitt with those very important people on board – by that time the Nazis were after her. I told you it was a bit of a long story. The new husband works at the embassy, some sort of high-up political attaché. They’ve been married about ten months, I think, and I have it on authority – all right, from my father, who has his own connections – that she now spends most of her time at her home in Kent with her daughter. Otherwise she’s up in town at her office working, probably only a couple of days a week though.’

‘Oh – a daughter?’

‘Adopted.’ Otterburn shrugged. ‘Actually, it’s a wonder she even speaks to me at all, because if it hadn’t been for my stupidity, she might not have suffered a stillbirth when her first husband – Viscount James Compton – was killed. It was the shock of witnessing the aeroplane come down that did it for her. James was testing a new kite in Ontario and was killed instantly. They were living in Canada at the time. I should have been flying that day but was nursing a terrible hangover.’

‘Good Lord, Elaine, I’m surprised you ever flew again.’

‘It’s a debt I’ll be paying for a long time, Jo, not least the reason for my wild night of drinking.’ She looked out of the window, then back at Jo Hardy. ‘You see, I had a terrible girlish crush on James Compton, and seeing his beloved wife heavy with child just about did me in.’ She paused. ‘Anyway, when this job came along, I knew I was in the right place with the right skills at the right time. Flying is all I know, and it’s my way to do my bit. The last thing I want is for anyone thinking I’m a snotty daddy’s girl.’ She opened her canvas shoulder bag, took out a notepad and pencil and began to write. ‘Here’s Maisie’s office address in Fitzroy Square, plus her telephone number. Look – you might even catch her today. And if you’re up for it later, we can get a drink in the bar at The Savoy, and you can stay at the house with me tonight, sleep it off before we make a dash for Hamble on the dawn train! It’s a big house, and it’ll just be us and a few servants – I suspect my father will be at his club. Or you can get a train down to Hampshire later today.’

Jo Hardy took the proffered sheet of paper. ‘Thanks, Elaine. Shall I say you sent me?’

‘I wouldn’t, if I were you.’

‘Sandra, it’s been a busy day. You should get on and catch your train home to Chelstone. I am more than ready to go back to the flat and a nice comfy armchair too.’ Maisie Dobbs glanced at the clock on the mantelpiece as she took a clutch of papers from her secretary and pushed them into her document case. ‘Come on, I’ll lock up and walk to the tube with you.’

‘At least I managed to get through the paperwork backlog.’ Sandra stood up and reached for her hat.

‘For which I am very grateful! And I wish I were coming down to Chelstone too, but I’ll be home tomorrow,’ said Maisie. ‘However, Mark said he’s cooking my favourite meal tonight, which means he’s cooking his favourite meal.’

‘Not spaghetti again.’

‘I hate to say this, Sandra, but I sometimes wish he wasn’t able to get hold of the exact ingredients, but being an American, there’s all sorts of things he’s able to acquire for us.’

‘Chocolates come to mind!’

Maisie laughed. ‘I can take a hint. I’ll “acquire” some for you.’ At that moment, the doorbell rang.

‘I bet that’s Billy forgotten his keys again,’ said Sandra.

Maisie shook her head. ‘He’s going straight back to Kent today – he wants to tell Doreen about the meeting with MacFarlane this morning.’ The doorbell sounded again. ‘You go on without me, Sandra, and I’ll deal with whoever it is – and thank you for sorting us out. We would suffocate under the mound of unfiled papers if it weren’t for you coming in once a week.’

As Maisie opened the door, the young woman outside had already turned to walk away.

‘Excuse me!’ Maisie called out, while waving goodbye to Sandra, who waved back before running towards Warren Street tube station.

‘Are you Miss Maisie Dobbs?’ asked the woman as she approached Maisie. ‘I’m terribly sorry to call upon you so late in the day, but I don’t have much time in London, and – well, you seem to be leaving.’

‘It’s something I try to do – get home before it’s too late so I can run down to the cellar if there’s an air raid. You’re lucky to catch me.’

‘My name is Josephine Hardy – Jo, actually. A friend said you could help me.’

Maisie looked at the woman, identifying her uniform. ‘And would that friend be Elaine Otterburn?’ She didn’t wait for an answer. ‘Come along, Jo Hardy – you’d better come up to my office and tell me what this is all about.’

CHAPTER TWO

It was dark when Maisie left the office. She wished she had a motor car at her disposal, though even if she had, she would have to face driving home with headlights covered so only a pinprick of light illuminated the road ahead. Instead, she was in time to use the tube; it would be another three hours before the trains stopped running and stations became the domain of exhausted Londoners seeking shelter from the German bombers that would surely sweep across the capital before morning. Women and children were already making their way down to the platform, seeking safe harbour for the night. Maisie walked with care lest she trip over a foot or step on someone’s leg, though most of those who came had not yet laid out their bedrolls and blankets, and were instead just getting settled, setting out flasks of tea and tins of sandwiches.

Once on the train, Maisie leaned back in her seat and closed her eyes. As the train rumbled underneath London, she thought about her meeting with Jo Hardy, who had spent over an hour at the office telling a story that all but beggared belief.

Maisie knew that as a first officer in the ATA, Hardy was among the most accomplished civilian pilots and that she earned nearly as much as a man for doing the same job – a rarity indeed. It had been reported that within another year, female ferry pilots would be the only government employees who could boast the same pay as their male counterparts. But what to make of the young woman’s story? And how could Maisie possibly help her? Jo Hardy had come to her for two reasons. One, because she was determined to find a way to clear the name of an American soldier. Having found him in dreadful circumstances, the young woman had taken responsibility for the life of Private Matthias Crittenden. Maisie turned the name around in her mind. If it weren’t for his colour, with a name like that the man could have come from Kent – it was, after all, a typical Kentish name, ending in den, the Anglo-Saxon word for a clearing in the woods. Hadn’t so many towns and villages throughout the county once begun as a clearing in the woods? It was an irony that, translated into Old English, the surname meant Matthias was ‘a man living in woodland.’ And his Christian name? She was no expert on the origin of names, but she knew this – Matthias was akin to Matthew, and hadn’t the apostle Matthew been an honourable man chosen to replace Judas Iscariot? Maurice Blanche, her former mentor, would have said there was a connection in those names, an association worthy of attention. However, she suspected the American’s forebears might well have been shipped to the United States as slaves and subsequently given the name of a colonial landowner whose own ancestors hailed from Kent or a close neighbouring county. Now Crittenden was in custody in Britain, and the woman who had come to his rescue had no means of knowing what might be in store for the young American – but she wanted Maisie to find out.

Maisie pictured Jo Hardy in her mind’s eye. Though not as tall as Maisie – Hardy was about five feet, five inches – she exuded a certain physical presence. It was the demeanour of one who had never known want, who assumed there would be opportunities in life because anything she wanted had always been available to her – though Maisie wondered to what extent the young woman might be oblivious to the trials and tribulations of those less fortunate. And yet there was something in the way Hardy had described Crittenden – how she recounted releasing the binding on his feet and wrists, how she had to calm him when she realised that he was as terrified of being reunited with his fellow Americans as he was of remaining a hostage in the barn – that suggested a woman of compassion. She had an immediate understanding that Crittenden was also fearful of being alone with a white woman.

Then there was the second remit, that of finding out who had aimed a weapon at Jo Hardy and who may also have caused the death of her fellow aviatrix, Erica Langley. Hardy hoped that Crittenden might have some information to assist in the enquiry; that even though she had found the poor man bound and gagged, something he had seen or heard might identify the gunman. Maisie wondered how on earth she would gain an interview with an American who could well be under suspicion of committing a crime against another soldier.

Hardy had concluded their meeting with a question: ‘I want you to work for me, and I know you can’t do it for nothing. What’s your fee?’ She had not blinked an eye as Maisie wrote down an estimate on a sheet of paper, and pushed it towards her. Maisie realised later that she had deliberately overestimated her charges in the hope that Hardy would withdraw interest in the enquiry. Instead the woman nodded, pulled a chequebook from her kit bag and paid the required retainer in full.

Now Maisie had to earn every penny.

‘Hi hon,’ a voice called out from the kitchen as Maisie closed the front door of her Holland Park garden flat and slipped her keys onto one of the coat stand hooks.

‘Sorry I’m a bit late, darling – a late case came in.’ She removed her black woollen coat and a paisley scarf and unpinned her black, Robin Hood–style hat with a brown band, then hung both on another hook alongside a mirror. ‘And of course the tube took ages – we were stuck in a tunnel for a long time,’ she added, leaning forward to see if she could detect any more threads of grey in her jet-black hair.

Her husband of ten months, Mark Scott, was chopping vegetables in the kitchen, and as she entered he turned towards her, leaning in with a smile and a kiss.

‘That’s better,’ said Scott. ‘Wine’s in the icebox. And I’m doing something else with the pasta tonight.’

‘Tuesday is always pasta night,’ said Maisie. ‘But you know, I can cook too, Mark. I promise my skills run to more than soup with bread and cheese.’ She uncorked a bottle of white wine and took two glasses from a cupboard.

‘It’s my way of relaxing, of mulling over things, and it’s the one night I can escape work early. You can get a lot out of your system, chopping with a good knife.’

‘Hmm … I prefer to walk. Maurice always said that to move the body is to move the mind, and he also said it opens up a door into the sixth sense.’