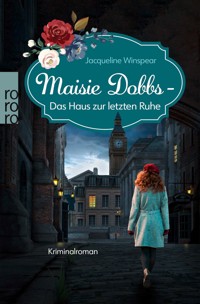

9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Maisie Dobbs

- Sprache: Englisch

London, 1933. Two months after an Indian woman, Usha Pramal, is found murdered, her brother turns to Maisie Dobbs to find the truth about her death. But Maisie's investigation becomes clouded by the unfinished business of a previous case and at the same time her lover, James Compton, gives her an ultimatum she cannot ignore...

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 516

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

LEAVING EVERYTHING MOST LOVED

A Maisie Dobbs Novel

JACQUELINE WINSPEAR

To my family – all of you, Wherever you are in the world or wherever you may roam: godspeed.

The family, that dear octopus from whose tentacles we never quite escape, nor in our innermost hearts never quite wish to.

DODIE SMITH

You shall leave everything loved most dearly, and this is the shaft of which the bow of exile shoots first. You shall prove how salt is the taste of another man’s bread and how hard is the way up and down another man’s stairs.

DANTE, PARADISO

All the people like us are We, and everyone else is They.

RUDYARD KIPLING, ‘WE AND THEY’

I have learnt that if you must leave a place that you have lived in and loved and where all your yesteryears are buried deep, leave it any way except a slow way, leave it the fastest way you can.

BERYL MARKHAM, WEST WITH THE NIGHT

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

PROLOGUE

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

SEVEN

EIGHT

NINE

TEN

ELEVEN

TWELVE

THIRTEEN

FOURTEEN

FIFTEEN

SIXTEEN

SEVENTEEN

EIGHTEEN

NINETEEN

TWENTY

EPILOGUE

About the Author

By Jacqueline Winspear

Copyright

PROLOGUE

London, July 1933

Edith Billings – Mrs Edith Billings, that is, proprietor of Billings’ Bakery – watched as the dark woman walked past the shop window, her black head with its oiled ebony hair appearing to bob up and down between the top shelf of cottage loaves and the middle shelf of fancy cakes as she made her way along with a confidence to her step. Mrs Billings considered herself to be a woman of some integrity, one who lived by the maxim ‘Live and let live’, but to be honest, she wondered what a woman like that might be doing on her street; after all, she should keep to her own patch. Billings’ Fine Bakery – or ‘Billingses’ as the locals called it – did a fair trade in morning coffee and afternoon teas, and Edith didn’t want her regulars, her ‘ladies’ as she referred to them, being upset by someone who had no business walking out of her own part of town. There were a lot of her kind, to be sure – you could thank the East India Company going back three hundred years for that – but all the same. On her street? That woman with her coloured silk, her jangling bracelets, her little beaded shoes – and, for goodness’ sake, just a cardigan to cover her arms. What’s she doing here? wondered Edith Billings. What does she want around these parts, with that red dot on her forehead? And what on earth happened to ‘When in Rome’, anyway? It’d be painted dots one minute, and curry with roast potatoes the next, if people weren’t careful.

Elsie Digby, aged six, was outside Billingses when the lady with the dark skin clad in silks of peach and pink walked towards her. She’d been left to rock the baby carriage while her mother bought a loaf of bread, and now she pushed back and forth with a solid rhythm against the carriage handle, yet with barely a thought to minding her new brother. The lady smiled as she approached, and Elsie blushed, looking at her feet in sensible brown lace-up shoes. She’d been told never to talk to strangers, and she was afraid the woman might speak to her, say a few words – and the woman was, if nothing else, a stranger. But as she came alongside Billingses and passed Elsie, a corner of the woman’s sari flapped against the girl’s bare arm. Elsie Digby closed her eyes when the soft silk kissed her skin, and at once she wondered what it must be like to be clothed in fine silk every day, to walk along with the heat of late summer rising up and bearing down, and to feel the cool brush of fabric touching her as if it were a night-time breeze, or breath from a sleeping baby.

Usha Pramal, respectfully dressed in her best sari, could feel the stares of passers-by. She smiled and said ‘Good morning’ when proximity brought the person within comfortable distance. There was no reply. There was never a reply. But she would shed no tears and worry not, because, according to Mr and Mrs Paige, their God was watching over her, as He watched over all His children. She had said a quick prayer to Jesus this morning, just to keep on acceptable terms with the Paiges and their deity, but she also bowed to Vishnu and Ganesh for good measure. Her father would have been appalled, but he would also have said, ‘Never burn your bridges, Usha. Never burn those bridges.’ She would not be here for long anyway. Her pennies and shillings were mounting, along with the pounds, and soon she would be able to afford to make her dream a reality; she would book her passage and at last return home. At last, after all this time, after seven long years, she would sail away from this grey country.

When the pain of separation seemed to rend her heart in two, it was her habit to walk to a street where there were shops that sold spices, where the aroma of familiar dishes cooking would tease her senses and set her stomach churning. And she could at least see faces that looked like hers; though at the same time, the sense of belonging was out of kilter, for many of those people had not been born in India and spoke in an unfamiliar dialect, or their names were constructed in a different manner. And even the other women in the hostel were not of her kind, though the Paiges thought they were all the same, like oranges in a bowl. Perhaps that’s what happened if you had only one God to watch over you. Yes, she was wise to honour the gods of her childhood.

Usha had left her customer’s house with a silver coin in her hand, a coin she would place in a velvet drawstring bag kept well inside her mattress, along with other coins earned. Whenever she added a florin or half-crown – riches indeed – it seemed to Usha Pramal that as she looked into the money nestled in the rich red fabric, it began to glow, like coals in a fireplace. And how she had worked to build that fire, to keep it alive. Soon she would have her ticket. Soon she would feel the damp heat of her own country, thick against her skin.

It was a tight little gang of street urchins, rambling along the canal path, who discovered the body of Usha Pramal. At first they aimed stones at the globe of coloured silk that ballooned from the green slime of city water, and then they thought they would use a broken tree branch to haul it in. It was only as they hooked the fabric that the body turned, the face rising in the misery of sudden death, the dead woman’s eyes open as if not quite understanding why there was a raw place on her forehead where a bullet had entered her skull. That morning, as Usha Pramal had painted a vermilion bindi to signify the wisdom nestled behind the sacred third eye, she could not have known that she had given her killer a perfect target.

ONE

Romney Marsh, September 1st, 1933

Maisie Dobbs manoeuvred her MG 14/28 Tourer into a place outside the bell-shaped frontage of the grand country house. She turned off the engine but remained seated. She needed time to consider her reason for coming to this place before she relinquished the security of her motor car and made her way towards the heavy oak door.

The red-brick exterior of the building appeared outlined in charcoal, as the occasional shaft of sunlight reflected through graphite-grey clouds scudding across the sky. It was a trick of light that added mystery to the flat marshlands extending from Kent into Sussex. The Romney Marsh was a place of dark stories; of smugglers, and ghosts and ghouls seen both night and day. And for some years this desolate place had offered succour to the community of nuns at Camden Abbey. Local cottagers called it ‘the nunnery’, or even ‘the convent’, not realising that Benedictines, whether male or female, live a monastic life – thus in a monastery – according to The Rule of Benedict.

It was the Abbess whom Maisie had come to see: Dame Constance Charteris.

Whether it was for advice that she had made the journey from London, or to have someone she respected bear witness to a confession of inner torment, she wasn’t sure. Might she return to her motor car less encumbered, or with a greater burden? Maisie suspected she might find herself somewhere in the middle – the lighter of step for having shared her concerns, but with a task adding weight to the thoughts she carried. She took a deep breath, and sighed.

‘Can’t turn around now, can I?’

She stepped from the motor car, which today did not have the roof set back, as there was little sun to warm her during the journey from London. Her shoes crunched against the gravel as she walked towards the heavy wooden doors. She rang a bell at the side of the door, and a few moments later a hatch opened, and the face of a young novice was framed against the ancient grain.

‘I’m here to see Dame Constance,’ said Maisie.

The nun nodded and closed the hatch. Maisie heard two bolts drawn back, and within a moment the door opened with a creaking sound, as if it were a sailing ship tethered to the dock, whining to be on the high seas once more.

The novice inclined her head, indicating that Maisie should follow her.

The small sitting room had not changed since her last visit. There was the rich burgundy carpet, threadbare in places, but still comforting. A mouldering coal fire glowed in the grate, and a wing chair had been set alongside another hatch. Soon the small door would open to reveal a grille with bars to separate the Abbess from her visitor, and Dame Constance would offer a brief smile before bowing her head in a prayer. Maisie would in turn bow her head, listen to the prayer, and echo Dame Constance as she said, ‘Amen.’

But first, before the Abbess could be heard in the room on the other side of the grille, when her long skirts swished against the bare floorboards with a sound that reminded Maisie of small waves drawing back against shingle at the beach, she would offer her own words to any deity that might be listening. She would sit in the chair, calm her breathing, temper her thoughts, and endeavour to channel her mind away from a customary busyness to a point of calm. It was as if she were emptying the vessel so that it could be filled with thoughts that might better serve her.

The wooden hatch snapped back, and when Maisie looked up she was staring directly at Dame Constance. The Abbess always seemed beyond age, as if she had transcended the years, yet Maisie remembered a time when her skin was smoother, her eyes wider, though they never lost an apparent ability to pierce the thoughts of one upon whom her attention was focused.

‘Maisie. Welcome to our humble house. I wonder what brings a woman of such accomplishment to see an old nun.’

Maisie smiled. There it was, that hint of sarcasm on the edge of her greeting; a putting in place, lest the visitor feel above her station in a place of silent worship.

‘Beneath the accomplishment is the same woman who was once the naive girl you taught, Dame Constance.’

The Abbess smiled. It was what might be called a wry smile, a lifting of the corner of the mouth as if to counter the possibility of a Cheshire cat grin.

‘Shall we pray first?’

Dame Constance allowed no reply, but bowed her head and clasped her hands on the shelf before her, her knuckles almost touching the bars of the grille separating Maisie and herself. Maisie rested her hands on her side of the same shelf, feeling the proximity of fingers laced in prayer.

She recognised the words of Saint Benedict as Dame Constance began.

‘And let them pray together, so that they may associate in peace.’

When the prayer was finished, when Maisie had echoed Dame Constance’s resolute ‘Amen’, the Abbess allowed a moment of silence to envelop them as she folded her arms together within the copious sleeves of her black woollen habit.

‘What brings you to me, Maisie Dobbs?’

Maisie tried not to sigh. She had anticipated that first question and had sampled her answer, aloud, a hundred times during the journey to Romney Marsh. Now it seemed trite, unworthy of the insight and intellect before her. Dame Constance waited, her head still bowed. She would not shuffle with impatience or sigh as a mark of her desire to be getting on with another task. She would bide her time.

‘I am troubled … I feel … No. I have a desire to leave, to go abroad, but I am troubled by the needs of those to whom I feel responsibility.’ Maisie picked at a hangnail on her little finger. It was a childhood habit almost forgotten, but which seemed to claim her when she was most worried.

Dame Constance nodded. To one who had not known her, she may have seemed half asleep, but Maisie knew better, and waited for the first volley of response with some trepidation.

‘Do you seek to leave on a quest to find? Or do you wish to run from some element of life that is uncomfortable?’

There it was. The bolt hit the target dead centre, striking Maisie in the heart. Dame Constance raised her eyes and met Maisie’s once more, reminding her of an archer bringing up the bow, ready to aim.

‘Both.’

Dame Constance nodded. ‘Explain.’

‘Last year …’ Maisie stopped. Was it last year? Her mind reeled. So close in time, yet almost a lifetime ago. ‘Last year my dear friend Dr Maurice Blanche died.’ She paused, feeling the prick of tears at the corners of her eyes. She glanced at Dame Constance, who nodded for her to continue. ‘He left me a most generous bequest, for which, I confess, I have struggled to … to … become a good and proficient steward.’ She paused, choosing words as if she were selecting matching coloured pebbles from a tide pool at the beach. ‘I have made some errors, though I have found ways to put them right, I think; however … however, in going through Maurice’s papers, in reading his journals and the notes he left for me, I have felt in my heart a desire to travel, to go abroad. I believe it was in the experience and understanding of other cultures that Dr Blanche garnered the wisdom that stood him in good stead, both in his work and as a much-respected friend and mentor to those whose paths he crossed. Of course, he came from a family familiar with travel, used to expeditions overseas. But I now have the means to live up to his example, so I have this desire to leave.’

‘I see. And on the other hand?’

‘My business. My employees. My father. And my … well, the man who loves me, who is himself making plans to travel to Canada. For an indefinite stay.’

Dame Constance nodded and was silent. Maisie knew it would not be for long. She’s just lining up the ducks to shoot them down, like a marksman at the fair.

‘What are you seeking?’

‘Knowledge. Understanding. To broaden my mind. I … I think I am somewhat narrow-minded, at times.’

‘Hmmm, I wouldn’t doubt it, but we all suffer from tunnel vision on occasion, Maisie, even I.’ Dame Constance paused. Again there was the catch at the corner of her mouth. ‘And you think journeying abroad will give you this knowledge you crave?’

‘I think it will contribute to my understanding of the world, of people.’

‘More so than, say, the old lady who has lived in the same house her entire life, who has borne children both alive and dead? Who tends her soil; who sees the sun shine and the rain fall over the land, winter, spring, summer, and autumn? What might you say to the idea that we all have a capacity for wisdom, just as a jug has room for a finite amount of water – pouring more water in the jug doesn’t increase that capacity.’

‘I think there’s room for improvement.’

‘Improvement?’

Wrong word, thought Maisie. ‘I believe I have the capacity to develop a greater understanding of people, and therefore compassion.’

‘And you think people want your compassion? Your understanding?’

‘I think it helps. I think society could do with more of both.’

‘Then why not take your journey, your Grand Tour, to the north of England, or to Wales, to places where there is want, where there is a need for compassion and – dare I say it – some non-patronising, constructive help from someone who knows what it is to be poor? You have much to offer here, Maisie.’

‘I take your point, truly I do – but I think going abroad is the right thing to do.’

‘Then why ask me?’

‘To align my thoughts on the matter.’

‘I see.’ Dame Constance paused. ‘And what of those you say you cannot leave – your employees? Your father? The man who loves you? Maisie, I know you well enough to know that you could find new positions for your employees, if you wish. Your father, by your own account, is a fiercely independent man – though I could understand a certain reticence to leave, given his age. And your young man? Well, I suspect he’s not so young, is he? I imagine he would want you to go with him, as his wife.’

Maisie nodded. ‘Yes, he has made that known.’

‘And you don’t want to?’

‘I want to take my own journey first.’

‘Your pilgrimage.’

‘My pilgrimage?’

‘Yes, Maisie. Your pilgrimage. Where do you intend to go?’

‘In reading Maurice’s journals, it seems he spent much time in the Indian subcontinent. I thought I might travel there.’

‘Do you know anyone there? Have you any associations?’

‘I am sure there are people who knew Maurice, who would offer me advice.’

‘“Pilgrimage to the place of the wise is to find escape from the flame of separateness.”’

‘I beg your pardon,’ said Maisie.

‘It’s something written by the Persian poet Jalāl ad-Dīn Muhammad Rūmī, from a more recent translation, though most of his work remains in his original language.’

‘But …’

‘I believe the words you find most startling are “the flame of separateness”.’

Maisie nodded.

‘Then go. Go to find out who you are – Know Thyself, as written at the entrance to Delphi. Know thyself, Maisie Dobbs, for such knowledge is freedom. Extinguish the flame of doubt that has burned in you for so long, and which – I suspect – stands between you and a deeper connection to someone with whom you might spend the rest of your life.’

‘There are more recent reasons for that separateness, Dame Constance. Matters of a confidential nature.’

‘You would not have come had you not felt trust.’

‘James – the man with whom I have been, to all intents and purposes, walking out with for some months now …’ Maisie paused. A year. In truth a year had passed without engagement, cause for some gossip within their social circle. ‘James is associated with certain men of influence and power, one of whom I have had cause to cross. I know the man orchestrated the death of another man – one I knew and had affection for – though it was not by his own hand, he has others to do his … dirty work. He is a powerful man who at the same time is serving our country in matters of international importance, and is therefore untouchable.’

Dame Constance bowed her head, then looked up at Maisie again.

‘So, I suspect you feel compromised. I know of your work, and it would seem that you were powerless against a man who is beyond the law, so you have become disillusioned with the law.’

‘Disillusioned with myself, I think. And though I grasp why James must follow this man, I find I admire him for wanting to be of service, yet sickened that it requires him to throw in his lot with such a person.’

‘So, perhaps the leaving is to set this episode behind you, to distance yourself from the grief associated with death, and also with a feeling that you have failed because you could not win against those who ensure that this man you speak of will be able to evade justice. But remember this, Maisie – according to The Rule of Benedict, the fourth rung of humility requires us to hold fast to patience with a silent mind, especially when facing difficulties, contradictions – and even any injustice. It asks us to endure. Thus I would suggest that you might well see justice done, in time. Patience, Maisie. Patience. Now go about your work. Seek the knowledge you crave, and remember this: you have expressed your desire, so be prepared for opportunity. It may come with greater haste than your preparations allow.’ She paused, and there was silence for what seemed like a quarter of an hour, though it might only have been a minute. ‘I am sure that, because you have voiced your desire to venture overseas, a direction will be revealed to you. Now, lest I be thought of as heathen, I should balance the esteemed Persian poet with our beloved Benedict.’

The Abbess met Maisie’s gaze; neither flinched.

‘Listen and attend to the ear of your heart, Maisie. Before you leave, let us pray together.’

And though it was not her practice to pray, Maisie bowed her head and clasped her hands, wondering how indeed she might best attend to the ear of her heart.

TWO

London, September 4th, 1933

Sandra Tapley, secretary to psychologist and investigator Maisie Dobbs, placed her hand over the cup of the black telephone receiver as Maisie entered the office.

‘It’s that Detective Inspector Caldwell for you.’ She rolled her eyes; Sandra bore a certain contempt for the policeman.

Maisie raised her eyebrows. ‘Well, there’s a turn-up – wonder what he wants.’

She took the receiver from her secretary’s hand, noticing the telltale signs of bitten nails.

‘Detective Inspector, to what do I owe this pleasure, first thing in the morning?’ As she greeted her caller, Maisie watched the young woman return to her typing.

‘Good morning to you, too, Miss Dobbs.’

‘I thought you liked to get down to business, so I dispensed with the formalities.’

‘Very good. Now then, I wonder if I could pay a visit, seeing as you’re in.’

‘Oh dear, spying on me again, Inspector? Now that we’re off to such a good start, I’ll get Mrs Tapley to put the kettle on in anticipation of your arrival.’

‘Fifteen minutes. Strong with—’

‘Plenty of sugar. Yes, we know.’

Maisie returned the receiver to its cradle.

‘I can’t stand that man,’ said Sandra, stepping out from behind her desk. ‘He needles me something rotten.’

‘He likes needling people, and I shouldn’t really needle him back, but he seems to be so much more accommodating when he’s had that sort of conversation – there are people who, for whatever reason, always seem to be on the defensive, and they’re better for being a bit confrontational. If they were taps, they would be running brown water first thing in the morning. At least he’s not as bombastic as he used to be – and he’s coming to me about a case, which is the first time he’s done that. It must be something out of the ordinary, to bring him over here. Or someone’s breathing down his neck.’

‘I’ll keep out of his way then.’

‘No, don’t. I’d like you to be here – and what time did Billy say he’d be back?’

‘Around ten. He went over to see one of those reporters he knows, about that missing boy.’

‘Finding out more about how the press covered the story, and what they might have known but didn’t report, I would imagine.’ Maisie looked at the clock. ‘Looks like Billy will cross the threshold at about the same time as Caldwell and whichever poor put-upon sergeant he brings with him this time.’

Detective Inspector Caldwell, of Scotland Yard’s murder squad, did indeed arrive on the doorstep of the Fitzroy Square mansion at the same time as Billy Beale, assistant to Maisie Dobbs. And he was not alone, though the man accompanying Caldwell was not a police sergeant, but a distinguished gentleman who wore an array of service medals. Maisie watched from the window as Billy greeted Caldwell in his usual friendly hail-fellow-well-met manner. Caldwell shook his outstretched hand, and in turn introduced the gentleman. Billy must have recognised that the visitor had served in the war, because he at once stood to attention and saluted. The man returned the salute, then gave a short bow and extended his hand to take Billy’s. Billy shook the man’s hand with some enthusiasm, and Maisie was at once touched to see the respect Billy accorded the visitor. Her assistant had served in the war, had been wounded, and still suffered the psychological pain inflicted by battle. The war might have been some fifteen years past, but there was a mutual regard between men who had seen death of a most terrible kind. Given the colour of his skin, his shining oiled hair, and his bearing, the man who Billy was escorting up to the office along with Caldwell had likely served with one of the Indian regiments that had come to the aid of King and Country.

Maisie could hear Billy’s distinctive footfall on the stairs and his voice as he welcomed the visitors, asking if the Indian gentleman had been in London long. Sandra was already setting out cups and saucers, and the tea was brewed in the pot, ready to pour.

‘Miss Dobbs, may I have the pleasure in introducing Major Pramal – he served with the Engineers in the war. We didn’t know each other, but Major Pramal said he’d met my commanding officer.’

‘I’m delighted to meet you, Major Pramal. And good morning, Detective Inspector Caldwell – you’ve been a stranger.’

The Indian gentleman was about to return Maisie’s greeting when Caldwell interrupted.

‘I thought you were about to say just “strange” then,’ said Caldwell, removing his hat and taking a seat before being invited to do so. ‘I’ve been busy, Miss Dobbs.’

‘Please, Major Pramal.’ Maisie held out her hand towards a chair.

‘I am honoured to make your acquaintance, Miss Dobbs, though please forgive me for correcting you – I was not a major in the war, as I am sure Mr Beale already knows; it was not possible for an Indian man to be a commissioned officer until after the war – I was a Sergeant Major.’ He was seated, and then went on. ‘No, only British officers could command us until 1919. In any case, I would prefer to be known as simply “Mr Pramal”, though as I said, I appreciate Mr Beale’s respect for my contribution.’

Maisie looked at Billy and suspected he had made the deliberate error to antagonise Caldwell – it seemed to be a sport among her employees.

Sandra handed cups of tea to the guests, and Billy pulled up a chair alongside Maisie’s.

‘Well, we’ll get straight to the point, Miss Dobbs,’ said Caldwell. ‘Sergeant Major – I mean, Mr Pramal – has come a long way, from India, on account of the fact that his sister was discovered dead.’

‘Oh, I am so sorry, Mr Pramal. Please accept our deepest sympathies for your loss – and your sister was such a long way from home.’

‘Indeed, Miss Dobbs. We miss her from the deepest place in our hearts, but my family was very proud of Usha. She had been the governess with an important family – a governess, mind you. Very important person in the bringing up of children.’

Caldwell rolled his eyes, and Maisie saw that Sandra had witnessed the look and was shaking her head.

‘How can I help? Inspector?’ asked Maisie.

‘Mr Pramal here is – understandably, I’ll grant you – not very happy with the police investigation, and—’

‘My sister was murdered, Miss Dobbs. In cold blood, her life was taken. It was no accident. A bullet at short range is never an accident.’

Maisie looked at Caldwell. ‘Inspector?’

‘Mr Pramal has a point. We’ve drawn a blank. I’ve had some of my best men on this case, and still not a hint as to who might have murdered Miss Pramal. When Mr Pramal came to us, he pointed out that he had knowledge of your services, and that he intended to come to you directly if we didn’t bring you into the fold. I felt it would be better if we kept ourselves apprised of what steps you might take towards a satisfying conclusion. So we’re here together.’

‘I see. Right.’ Maisie looked at Billy, then glanced at Sandra before she stood up from her chair and walked to the window. Caldwell had told her only part of the story, so she could either challenge him – ask for more details – or she could take his account as truth, and accept the case. Or she could turn them both away, saying she had too much work at the moment. It would have been a lie, but she wondered if she really needed the annoyance of working with Caldwell of Scotland Yard.

But as she turned back into the room, having been with her thoughts for only half a minute, Maisie saw something in Pramal’s eyes, a look of despair, of yearning. His eyes were those of a man who had been strong, but was now almost beaten by grief. It was as if the bones in his body, used to a certain correct posture, were all that stood between him and collapse. Now there was no choice. They were all looking at her: Billy, Sandra, Caldwell, and Pramal.

‘Mr Pramal … we should begin. Time is always of the essence in this sort of case – and so much time has been lost already.’ She glanced at Caldwell. ‘How long since Miss Pramal’s body was discovered?’

Caldwell reddened. ‘About two months now, I’m sorry to say it, but we hit a dead end early on, and never picked up the lead. And of course, Mr Pramal has had a very long journey from India – weeks.’

‘Where did it happen?’

‘Camberwell. That’s where the body … where Miss Pramal was found. In the canal.’

‘All right. Here’s what I think we should do, if I may make a suggestion, Inspector Caldwell? Perhaps Mr Pramal could remain here for a while, just to give us his viewpoint.’ Maisie turned from Caldwell to the Indian gentleman. ‘Would that be convenient?’

The man bowed his head, then looked at Maisie. ‘I have all the time needed, for my sister.’

‘Good. Inspector, perhaps I could visit you later, at the Yard, and we can discuss the case – I am sure there will be no problem in allowing me to view your investigation records, in the circumstances.’

‘In the circumstances—’

‘Good,’ said Maisie, cutting off any dissent that Caldwell might have expressed. ‘In that case, Inspector, I’ll walk with you down to your motor car.’

As they stood on the downstairs threshold, Maisie folded her arms against a cool breeze that had blown up to chill a fine day in what promised to be one of the warmest Indian summers she could remember.

‘What happened? It’s not like you to lose the thread – assuming you found it,’ said Maisie.

Caldwell shrugged. ‘I’ve had a lot on my plate, Miss Dobbs. She was an Indian woman, knew hardly anyone, and she turns up dead. There was no one pressing me for a result, so it went to the bottom of the pile – mind you, we had a go at finding who did it, but it’s not as if there was anyone to answer to, and the press weren’t all over it – no grieving relatives, nothing your Daily Mails and Mirrors could make hay with. Then he comes along – the brother. Of course, it takes, what – six weeks to come over on the boat? There had been a letter saying he was on his way, but I suppose it went into the file and the next thing you know—’

‘She wasn’t the right colour, so no one bothered.’

‘Now, don’t be like that, Miss Dobbs. You know me, straight as a die – I don’t make any distinction whether the deceased is one of us or not.’

Maisie sighed. ‘You know my usual fee?’

‘Only too well. So does the commissioner, and the bookkeeper.’

‘Tell him to keep that chequebook at the ready.’

‘Tell her. The bookkeeper who deals with my department is a she.’

‘Good. I’ll be paid on time then.’ Maisie looked at her wristwatch. ‘About four?’

Caldwell nodded, turned away from Maisie and raised his hand. A black police motor car moved from the place where it was parked and approached at a snail’s pace.

Maisie half-turned to go back into the mansion where her first-floor office was housed. ‘Don’t worry, Inspector, I’ll keep you posted all the way along. And I will find the killer.’

‘I know you will, Miss Dobbs.’

‘How do you know?’

Caldwell put his hat back on. ‘Because you’re a terrier, Miss Dobbs. You might not be quick, and you might not go about it like I would, but you never let go. Now then, you go and get your teeth into his story. See where that leads you.’

Maisie waved and made her way back up the stairs to her office. Caldwell was right, she wouldn’t let go. She couldn’t, because fifteen minutes earlier, when she’d turned from the window and looked into Pramal’s eyes, she had seen the open wound across his soul that the death of his sister had inflicted upon him. And Maisie Dobbs could never turn away from such an entreaty.

‘Now then, before we begin, Mr Pramal, would you like more tea, or have we soaked you?’ Maisie smiled and nodded to Billy, who pulled the chairs into a circle. He had already allowed for Sandra to join them.

‘No thank you, Miss Dobbs. I have had sufficient refreshment.’

‘So, you returned to India after the war – did you remain in the army?’ Maisie made small talk while Billy and Sandra took their places, both with notebooks ready.

‘For a while, yes. I left the service in 1920, and I am now a civil engineer with a company in Bombay, though I spend much time in other places, mainly working on water flow – irrigation, for example – and bridges.’

‘Sergeant Major Pramal was an explosives man in the war – tunnelling and laying explosives. Not very good for the heart, that. Takes a very calm man to do the job of blowing things up,’ added Billy.

Pramal smiled. ‘I am pleased to be the recipient of your respect, Mr Beale, and I understand addressing me by my army rank is ingrained in the soldier when he sees the medals, but I am happily no longer in the service of the King and Emperor.’

‘But you wear your medals with much pride, Mr Pramal,’ said Maisie.

‘They have their uses – for example, when I wanted to be heard at Scotland Yard. There are men there who might have passed me in the street, looking the other way, but if they’ve had military training – which many have – it remains locked in the memory, so they could not help but accord me respect when they saw my medals. In a few hours with your police force I think I was saluted more than at any other time since the war.’

Maisie smiled. ‘We are grateful to you, Mr Pramal.’ She paused. ‘Now then, this is how we go about our business, especially in an initial conversation with a new client. Though we could easily read through a series of reports provided by Inspector Caldwell, we conduct our own interview first. You may already have answered questions, and I realise there is much you cannot answer, but this helps us. The reason we are all sitting here is that we all listen in different ways, and something I miss might be noticed by either Mr Beale or Mrs Tapley.’

The man pressed his hands together and bowed again. ‘I am grateful for your attention. Please ask your questions.’

Maisie began.

‘Let’s start with Usha. How old was she?’

‘My sister was twenty-nine years of age, last birthday, April 15th.’

‘How long had she been in England?’

‘She sailed with the family approximately seven years ago. It might be more. Sometimes it seems only yesterday, but at other times I can hardly remember her features.’

‘Do you have the name of the family who brought her here? What about an address?’

‘The Allisons. Lieutenant Colonel Allison, his wife, and three children, who were then – if my memory serves me well – two, four, and six.’

‘He was an army man?’ Billy interjected.

‘Not at the time. He was a civil servant, with the British foreign service, as far as I know, though his army achievements were sufficiently impressive for him to continue using the form of address to which he was entitled. His wife advertised for a governess for the children, so my sister applied and was accepted for the position. She was a trained teacher, Miss Dobbs. She was with them for almost two years before they left to return to Great Britain, and she came with them.’

‘I see. Did she want to come here? How did she feel about the journey, about leaving her home?’

Pramal sighed, and Maisie remembered her father, at a time when her mother was so ill, taking more money from the savings tin to go to yet another doctor. He’d slump into the chair after carrying her mother upstairs to bed. ‘It’s the telling of it all that wearies us, Maisie. They look at you, these doctors, and you can see that not one of them is thinking any differently from the others, as if they’ve all read the same book. But you keep on going, trying to find the doctor who’s writing a new book, not just taking his knowledge out of the old ones.’ Pramal, too, seemed tired of the telling.

‘Usha was a headstrong girl, Miss Dobbs. We are a well-to-do but not a wealthy or aristocratic family such as you might find here, though the war allowed me to achieve some measure of, well, professional stature. My father was broad-minded, and believed in the value of education for a woman. But perhaps that was the downfall for Usha – she did not want to be married, not at the time, and the fact that our mother was dead did not help matters; a young woman needs a mother to prepare her for womanhood, you see. Suitors were arranged, but she turned them away. My father did not insist and soon her chance was gone. She relished the thought of coming to Great Britain, and accepted the position knowing full well that she would leave her country, though I believe she expected to return. You see, she had plans.’

‘What plans?’

‘Usha wanted to found a school for girls. Not rich girls, but girls with promise who wouldn’t otherwise go to school, or who had had their education curtailed. She wanted to save money, and perhaps to find a sponsor, someone who would enthusiastically support her endeavours.’

Maisie rubbed her forehead. ‘Mr Pramal, tell me what Usha was like. I want to know who she was, how people saw her.’

The man nodded, brought his hands together in front of his face, and then to his sides, grasping the chair as if for support.

‘As a child, clever and headstrong, questioning, and sometimes a bit of a know-it-all. She saw no division in people – no, that’s not true, she saw division, but she ignored it. She would touch a leper. She was very – I am not sure that I am explaining this well – she was very much a touching person. If she stopped to talk to a neighbour in the street, she would reach out—’ Pramal moved as if to touch Maisie, to demonstrate his sister’s way of being, but drew back his hand.

‘Do you mean like this?’ Sandra spoke up and touched Billy on the arm. ‘How do you do, Mr Beale? Isn’t it a lovely day?’ She swept her hand around the room, as if the sun were shining through the ceiling.

Pramal nodded and smiled, his face at once alive as if the memory of Usha had become sharper. ‘Very much so. And there was no intention in her touch, except to … except to … except to connect with that person, like one electrical wire to another. And no matter how many times reprimanded by my aunts and cousins, by friends of my mother who had tried to guide her, she would just laugh and do things her way. Her spirit was quite without discipline.’

Maisie was still looking at Billy’s arm, at the place where Sandra had placed her hand and, for a glimpse in time, seemed like another person. A spirit without discipline.

‘Do you have a photograph of your sister?’ asked Maisie.

‘Yes, here – I brought one for you.’ Pramal reached into his pocket and brought out a brown-and-white photograph, a portrait of a woman with large almond-shaped eyes, high cheekbones, and lips slightly parted, as if she were about to laugh, but managed to stop herself. Her hair seemed oiled, such was the reflection in the photograph, and though Maisie could only guess at the colours of the sari, she imagined deep magenta, a rosy peach, perhaps rimmed in gold, or silver. She touched the dark place on her forehead where Usha had marked her skin with a red bindi, and at once she felt pain between her own eyes. She handed the photograph to Billy.

‘She was a beautiful girl, Mr Pramal,’ said Billy.

Pramal nodded, as Billy passed the photograph to Sandra, who frowned as she studied the image.

‘What is it, Sandra?’ asked Maisie.

‘Nothing, Miss.’ She shrugged, handing the photograph back to Maisie. ‘No, nothing – she just looked sort of familiar, that’s all. But then they all – no, it’s nothing.’

‘May we keep the photograph?’ asked Maisie.

‘Indeed. I have others.’

‘Tell me what happened when she arrived here – where did she live?’

‘I would send letters to this address, in St John’s Wood.’ Pramal pulled a piece of paper from his pocket and gave it to Maisie. ‘This is the address. Later, she wrote that I should send my letters poste restante to a post office in south-east London.’

She nodded. ‘Where was she living when she died? Have the family been in touch?’

Pramal shook his head. ‘My sister was given notice within a few years of disembarking here in Great Britain. She was cast aside by the family, with nowhere to go, no money except that which was owed her. I did not know this until a long time afterwards – she did not want to bring shame on her family.’

‘But what happened to her?’

‘She found somewhere to live – in an ayah’s hostel, in a place called Addington Square. That’s probably why I was not given an address – she didn’t want me to know where she was living, and I think she also would not have wanted anyone else intercepting her correspondence.’

‘Addington Square’s in Camberwell,’ said Billy. ‘But what’s an ayah’s hostel?’

‘It’s where women live who were servants,’ Sandra interjected, leaning towards Pramal. ‘They call them ayahs, don’t they? Women who look after the children – they do nearly all the work so the mother doesn’t have to lift a finger. They come over with the family, and when the family doesn’t need them any more, that’s it – out on your ear in a strange country with nowhere to go.’ She looked at Maisie. ‘We talked about this problem at one of our women’s meetings – terrible it is. At least there are a couple of hostels for the women, though it doesn’t stop some from having to work as—’

Maisie shook her head. Sandra had become involved in what was being talked about as ‘women’s politics’ and would not draw back from confrontation. It seemed to Maisie that she had found her voice since the death of her husband – but on this occasion, she did not want Sandra to describe the ways in which a homeless ayah might be pressed to make enough money to keep herself.

‘So Usha found lodgings in an ayah’s hostel. And you had no knowledge of her situation until – when?’ asked Maisie.

‘Until about nine or ten months ago. I have a family, Miss Dobbs, so I did not have sufficient funds to pay for her immediate passage home – and she told me she had almost enough, so was planning to sail at the end of the year.’ He paused. ‘You see, she wasn’t only saving to come home – she wanted to bring enough money to open her school. She said she could earn better money here in London than in all of India, so she remained.’

Maisie could see fatigue in the lines around the man’s eyes and – as much as he fought it – knew it was in his backbone.

‘Mr Pramal, here’s what I would like to do now. I will be visiting the Allisons, and also the ayah’s hostel – I am sure we can find the address, if you don’t have it to hand. In the meantime, I think it best that you return to your hotel and rest. We should like to reconvene tomorrow morning – would nine o’clock suit you?’

‘Indeed, thank you, Miss Dobbs.’

Maisie stood up, pushing back her chair. Sandra returned to her desk, and Billy stood ready to escort Mr Pramal to the front door.

‘May I ask if you have satisfactory accommodations while you are in England?’ asked Maisie.

‘A small hotel, Miss Dobbs. It’s inexpensive, close to Victoria Station. I was staying with an old friend, but I did not want to inconvenience the family any longer.’

Maisie nodded. ‘Please do not hesitate to let me know if the hotel ceases to be comfortable. I am sure I can arrange another hotel, with help from Scotland Yard.’

Pramal gave a half-bow, his hands closed as if in prayer. ‘You are most kind.’ He turned to Sandra. ‘Thank you for the tea, Mrs Tapley.’

Billy extended out his hand towards the door and left the room with Pramal. While Sandra removed the tea tray, Maisie walked to the window again, where she watched Billy bid farewell to the former officer in the Indian Army. As if he couldn’t help himself, Billy saluted Pramal again, and was saluted in return. Each recognising a war fought inside the other.

THREE

‘I always thought women in India were sort of tied to the house until they married,’ commented Sandra, while marking the name ‘Pramal’ on a fresh cream-coloured folder. ‘Then we had this woman – a visiting lecturer – come along to talk to the class last week. She’s been standing in for someone else. A doctor, she is – not medical, but of something else; history, I think, or perhaps politics. It was a history class anyway. She was talking about imperialism and about Mr Gandhi, and what was happening in India, and how it would affect Britain. Very sharp, she was. Kept us all listening, not like some of them.’

Sandra continued talking as Maisie looked down at a page where she, too, had marked a name: Usha Pramal.

‘Not that there was any reason for her not to be intelligent, mind,’ Sandra went on. ‘But you know, I was surprised to see an Indian woman there, teaching us. She was very, very good – better than most of the men, I have to say.’

‘It seems Usha Pramal was of her ilk – her brother’s description reveals an educated woman with an independence of character,’ said Maisie. She looked up. ‘Do you have her name – your lecturer? I think I might like to see her, have a word with her; she could have some valuable information for us, perhaps, regarding Indian women here in London.’

‘She’ll be giving the lecture tomorrow evening. I’ve forgotten her name now, but I can find out when I get there.’

‘Thank you, Sandra.’ Maisie paused. ‘If it can be arranged, I would like to meet her – at this point, I think any information will be useful, even if it is removed from the case, it could shed light on how Usha Pramal might have lived. I fear more time has elapsed on this case than I would have wanted. Evidence will be thin, and we’ll be dependent upon the opinions and observations of people who might well have worked hard at forgetting whatever they knew about Miss Pramal. We need to draw in as much background information as we can.’

Billy returned to the room, smiling at Sandra, then at Maisie. ‘Nice bloke, eh?’

‘Yes, a very good man I think, Billy,’ said Maisie, standing up. ‘Let’s all take a seat by the window and get a case map started. I’ll be bringing back more information after I’ve seen Caldwell this afternoon.’

Billy took a roll of wallpaper, cut a length, and unfurled it upside down across the table, where he and Sandra pinned it in place. The wallpaper had been given to them by a painter and decorator friend of Billy’s, who often had surplus from his paper-hanging job. Maisie placed a jar of coloured crayons on the table – some of thick wax in bold primary colours, others fine pencils in more muted shades. She took a bright red wax crayon and wrote UshaPramal in the centre of the paper, circling the name. This was the beginning, the half-open shell in what would become a tide pool of ideas, thoughts, random opinions; of words that came to mind unbidden; and of threads connecting evidence gathered. Some of it would make sense, though much of it wouldn’t, but eventually something on the map, often one small buried clue, would point them to the killer. And a terrier could always find something buried, if she’d caught the scent.

‘Billy, we need to find the exact point on the Surrey Canal where the body was discovered. I’ll get more information from Caldwell; however, in the meantime, I don’t want to depend upon it, so would you go down to Camberwell, find out where she was found on the canal. Talk to anyone who might have witnessed something – remember, people would love to forget this, so carefully does it.’ She sighed. ‘Mind you, on the other hand, there are probably a few gossips who’d enjoy nothing more than a good old chinwag about a murder. In any case, could you also find out about movements on the canal that might have taken the body along. I believe timber is transported back and forth to the works there, from Greenland Docks or Rotherhithe – can you find out and ask around? See if any of the dockworkers saw anything of interest to us, or if anyone knows someone who did?’ Maisie pushed back her chair, and went to her desk, where she took a camera from a large desk drawer. ‘Use this. There’s film in the box, and it’s easy to operate – heaven knows, if I can take a photograph, anyone can! I have a neighbour who has a darkroom in his flat, so he’ll get them developed for us, and he’s quite quick about it.’ She handed the box containing her pawnshop purchase across the table to Billy – a Number Two C Autographic Camera, manufactured by the Eastman Kodak Company. ‘Study the instructions for a few minutes. I think it will help us to have some photographs of the area.’

Billy nodded. ‘Right you are, Miss. We should use this a lot more, I can see it being handy for our cases.’

‘Keep it in your desk drawer – I can always grab it if I need it. Anyway, back to Usha Pramal: though we’ll have names later, Billy, root out what you can about the boys who found the body – they were messing around along the canal path, probably getting up to harmless mischief. Now they’ll probably have nightmares for years, poor little mites. Anyway, Billy, you’re a father of boys, so you will know how to deal with them.’

‘It’s our girl who’s going to need dealing with, I can see it coming already. Nearly a year old and breaking hearts already.’

‘They always say that about the girls, but it’s the boys who break the hearts,’ said Sandra.

‘Not if I’ve got anything to do with it – no one will break my little girl’s heart.’

‘I’m sure they won’t, Billy,’ said Maisie, turning to her secretary. ‘Sandra, you said you thought you might have seen Miss Pramal before – have you had any recollection?’

Sandra shook her head. ‘I wish I had, Miss. At first I thought I might have seen her – and I’m sorry I nearly said it in front of her brother, but they all sort of look the same, when they’re from somewhere else like that. You know, your Chinese, your Indians. I’m sure you can see the differences if you live there and you’re used to the faces, but when you only see them now and again, you can’t always tell. That sounds really terrible, but, well, I think a lot of people get confused like that.’

Maisie sat back in her chair, tapping the crayon on paper, creating a series of dots. ‘You know, that might be something for us to bear in mind – what if Usha was not the intended victim? What if someone just got it wrong, and thought she was another person?’ She looked up at Sandra. ‘It’s a sad reflection upon us, if we’re that insular. After all, we’ve all nations under Britain’s roof and it’s not as if we’re short of people from other continents, here in London.’ She leant forward and wrote ‘mistaken identity?’ on the wallpaper, circled the words and then linked them with a line to Usha’s name.

Sandra spoke again. ‘It’s not that I go to many places in a day – I go from here to Mr Partridge’s office, or the house, or I go to classes at Morley College, or to Birkbeck – and I go back to my flat. I think I’ve only ever been to Camberwell once or twice, even though one of my friends I share the flat with goes to the art college there.’ She frowned, then looked at Maisie, her eyes wide. ‘Hold on a minute – I think I know where I saw her. Well, it might not have been her, as I said, but … about four months ago, must have been in May or thereabouts, my friend asked me to go with her to one of the lectures; open to the public, it was. The talk was all about colours and how things feel – textures, and that sort of thing. The lecturer had people helping him – it was all very interesting, I must say – and he was showing pictures these different artists had painted, and their sculptures, and what have you, and then he talked about colour and places, so she – if it was her – came onto the podium with this pile of saris, all these lengths of silk in different colours, and she opened one up after another, and draped them over her arms. I remember her standing there, like a goddess, she was, clothed in all these colours. Your eyes could hardly stand it.’

‘And you think this assistant was Usha Pramal?’ Maisie picked up the photograph, now some years old and torn at the edges. She handed it to Sandra.

The young woman frowned, and began to nibble the nail on the middle finger of her left hand. ‘Oh, dear – I can only say it looks like her, because I remember the woman smiling, really smiling, as if she’d turned into a butterfly. My friend was thinking the same thing, because she whispered in my ear, “She’s a Camberwell Beauty, if ever I saw one.” You know, the butterfly, the Camberwell Beauty?’ Sandra paused. ‘I couldn’t swear on the Bible in a court of law, Miss, but I am halfway positive that it was her.’

‘Any chance that your friend will remember the name of the lecturer?’

‘I’ll ask her tonight.’

Maisie nodded, and was about to put a question to Billy when Sandra spoke again.

‘I remember him as if it were yesterday, though I couldn’t tell you his name.’

‘Why? What was it about him that stuck in your memory?’

‘You could tell he’d been wounded, in the war. There were scars on his face, and he had a bit of a limp; used a cane.’

‘That’s a fair description of almost all of us who went over there,’ said Billy.

She shook her head. ‘Now I’m remembering – and I still don’t know for definite if it was her. But I remember the way he was talking, and he ran his hand along one of the saris she held over her arm, and she smiled this big smile at him. Then afterwards, he was helping her to fold the saris as we were all filing out – and it was slow going, what with people stopping to talk and picking up their things; the line was moving like treacle off a cold spoon. When they’d finished, the Indian woman went to shake his hand – which I thought was very bold of her, I mean, to hold out her hand like that. He looked at her hand as if it were something very precious he was being offered, and at the point where their fingers touched, she took his hand in both of hers. Then, when he turned away – the Indian woman was by now talking to some women that my friend said were students studying embroidery – he looked at his hand and rubbed it, as if he’d touched something warm.’ Sandra looked at Maisie, frowning. ‘I don’t understand that, how one minute you can be sorting things out in your brain, looking for something you’ve lost, then the next thing, the memory comes rushing in.’

‘It might be to do with the colour. I remember Maurice telling me that it opens up another part of the brain. Recalling all those saris and the explosion of colour was the key that unlocked the treasure chest with that particular memory.’ She turned to her assistant. ‘Billy, remember that. Remember the colour. I’ll ask Caldwell about the sari Usha was wearing when her body was discovered – we can get some similar fabric. It might help people remember.’

‘I’d better be off then, Miss. Got a lot to do today.’

‘Any luck with that other case, the missing boy?’