9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

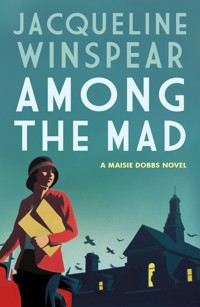

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Maisie Dobbs

- Sprache: Englisch

Christmas Eve, 1931. On the way to see a client, Maisie Dobbs witnesses a man committing suicide on a busy London street. The following day, the Prime Minister's office receives a letter threatening a massive loss of life if certain demands are not met - and the writer mentions Maisie by name. Tapped by Scotland Yard's elite Special Branch to be a special adviser on the case, Maisie is soon involved in a race against time to find a man who proves he has the knowledge and will to inflict destruction on thousands of innocent people. In Among the Mad, Jacqueline Winspear combines a heart-stopping story with a rich evocation of a fascinating period to create her most compelling and satisfying novel yet.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 467

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

AMONGTHE MAD

A Maisie Dobbs Novel

JACQUELINE WINSPEAR

Dedicated to my wonderful Godchildren:

Charlotte Sweet McEwan

Charlotte Pye

Greg Belpomme

Alexandra Jones

Keep True to the Dreams of thy Youth

Friedrich von Schiller

1759–1805

“But I don’t want to go among mad people,” Alice remarked.

“Oh, you can’t help that,” said the Cat. “We’re all mad here. I’m mad. You’re mad.”

“How do you know I’m mad?” said Alice.

“You must be,” said the Cat, “or you wouldn’t have come here.”

––LEWI S CARROLL,

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

A short time ago death was the cruel stranger, the visitor with the flannel footsteps … today it is the mad dog in the house. One eats, one drinks beside the dead, one sleeps in the midst of the dying, one laughs and sings in the company of corpses.

–– GEORGES DUHAMEL,

French doctor serving at Verdun in the Great War

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

SEVEN

EIGHT

NINE

TEN

ELEVEN

TWELVE

THIRTEEN

FOURTEEN

FIFTEEN

SIXTEEN

SEVENTEEN

EIGHTEEN

NINETEEN

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

About the Author

By Jacqueline Winspear

Copyright

AMONG THE MAD

ONE

London, Christmas Eve, 1931

Maisie Dobbs, Psychologist and Investigator, picked up her fountain pen to sign her name at the end of a final report that she and her assistant, Billy Beale, had worked late to complete the night before. Though the case was straightforward—a young man fraudulently using his uncle’s honourable name to acquire all manner of goods and services, and an uncle keen to bring his nephew back on the straight and narrow without the police being notified—Maisie felt it was time for Billy to become more involved in the completion of a significant document and to take more of an active part in the final interview with a client. She knew how much Billy wanted to emigrate to Canada, to take his wife and family away from London’s dark depression and the cloud of grief that still hung over them following the death of their daughter, Lizzie, almost a year earlier. To gain a decent job in a new country he would need to build more confidence in his work and himself, and seeing as she had already made enquiries on his behalf—without his knowledge—she knew greater dexterity with the written and spoken word would be an important factor in his success. Now the report was ready to be delivered before the Christmas holiday began.

“Eleven o’clock, Billy—just in time, eh?” Maisie placed the cap on her fountain pen and passed the report to her assistant, who slid it into an envelope and secured it with string. “As soon as this appointment is over, you should be on your way, so that you can spend the rest of the day with Doreen and the boys—it’ll be nice to have Christmas Eve at home.”

“That’s good of you, Miss.” Billy smiled, then went to the door where he took Maisie’s coat and his own from the hook.

Maisie packed her document case before reaching under the desk to bring out a wooden orange crate. “You’ll have to come back to the office first, though.”

“What’s all this, Miss?” Billy’s face was flushed as he approached her desk.

“A Christmas box for each of the boys, and one for you and Doreen.” She opened her desk drawer and drew out an envelope. “And this is for you. We had a bit of a rocky summer, but things picked up and we’ve done quite well—plus we’ll be busy in the new year—so this is your bonus. It’s all well earned, I must say.”

Billy reddened. “Oh, that’s very good of you, Miss. I’m much obliged. This’ll cheer up Doreen.”

Maisie smiled in return. She did not need to enquire about Billy’s wife, knowing the depth of the woman’s melancholy. There had been a time, at the end of the summer, when a few weeks spent hop-picking in Kent had put a bloom on the woman’s cheeks, and she seemed to have filled out a little, looking less gaunt. But, in London again, the routine of caring for her boys and keeping up with the dressmaking and alterations she took in had not lifted her spirits in any way. She ached for the milky softness of her daughter’s small body in her arms.

Maisie looked at the clock on the mantelpiece. “We’d better be off.”

They donned coats and hats and wrapped up against the chill wind that whistled around corners and blew across Fitzroy Square as they made their way toward Charlotte Street. Dodging behind a horse and cart, they ran to the other side of the road as a motor car came along in the opposite direction. The street was busy, with people rushing this way and that, heads down against the wind, some with parcels under their arms, others simply hoping to get home early. In the distance, Maisie noticed a man—she could not tell whether he was young or old—sitting on the pavement, leaning up against the exterior wall of a shop. Even with some yards between them, she could see the greyness that enveloped him, the malaise, the drooping shoulders, one leg outstretched so passers-by had to skirt around him. His damp hair was slicked against his head and cheeks, his clothes were old, crumpled, and he watched people go by with a deep red-rimmed sadness in his eyes. One of them stopped to speak to a policeman, and turned back to point at the man. Though unsettled by his dark aura, Maisie reached into her bag for some change as they drew closer.

“Poor bloke—out in this, and at Christmas.” Billy shook his head, and delved down into his coat pocket for a few coins.

“He looks too drained to find his way to a soup kitchen, or a shelter. Perhaps this will help.” Maisie held her offering ready to give to the man.

They walked just a few steps and Maisie gasped, for it was as if she was at once moving in slow motion, as if she were in a dream where people spoke but she could not hear their words. She saw the man move, put his hand into the inside pocket of his threadbare greatcoat, and though she wanted to reach out to him, she was caught in a vacuum of muffled sound and constrained movement. She could see Billy frowning, his mouth moving, but could not make him understand what she had seen. Then the sensation, which had lasted but a second or two, lifted. Maisie looked at the man some twenty or so paces ahead of them, then at Billy again.

“Billy, go back, turn around and go back along the street, go back …”

“Miss, what’s wrong? You all right? What do you mean, Miss?”

Pushing against his shoulder to move him away, Maisie felt as if she were negotiating her way through a mire. “Go back, Billy, go back …”

And because she was his employer, and because he had learned never to doubt her, Billy turned to retrace his steps in the direction of Fitzroy Square. Frowning, he looked back in time to see Maisie holding out her hand as she walked toward the man, in the way that a gentle person might try to bring calm to an enraged dog. Barely four minutes had passed since they walked past the horse and cart, and now here she was …

The explosion pushed up and outward into the Christmas Eve flurry, and in the seconds following there was silence. Just a crack in the wall of normal, everyday sound, then nothing. Billy, a soldier in the Great War, knew that sound, that hiatus. It was as if the earth itself had had the stuffing knocked out of it, had been throttled into a different day, a day when a bit of rain, a gust of wind and a few stray leaves had turned into a blood-soaked hell.

“Miss, Miss …” Billy picked himself up from the hard flagstones and staggered back to where he had last seen Maisie. The silence became a screaming chasm where police whistles screeched, smoke and dust filled the air, and blood was sprayed up against the crumbling brick and shards of glass that were once the front of a shop where a man begged for a few coins outside.

“Maisie Dobbs! Maisie … Miss …” Billy sobbed as he stumbled forward. “Miss!” he screamed again.

“Over ’ere, mate. Is this the one you’re looking for?”

In the middle of the road a costermonger was kneeling over Maisie, cradling her head in one hand and brushing blood away from her face with the kerchief he’d taken from his neck. Billy ran to her side.

“Miss … Miss …”

“I’m no doctor, but I reckon she’s a lucky one—lifted off her feet and brought down ’ere. Probably got a nasty crack on the back of ’er noddle though.”

Maisie coughed, spitting dust-filled saliva from her mouth. “Oh, Billy … I thought I could stop him. I thought I would be in time. If only we’d been here earlier, if only—”

“Don’t you worry, Miss. Let’s make sure you’re all right before we do anything else.”

Maisie shook her head, began to sit up, and brushed her hair from her eyes and face. “I think I’m all right—I was just pulled right off the ground.” She squinted and looked around at the melee. “Billy, we’ve got to help. I can help these people …” She tried to stand but fell backward again.

The costermonger and Billy assisted Maisie to her feet. “Steady, love, steady,” said the man, who looked at Billy, frowning. “What’s she mean? Tried to stop ’im? Did you know there was a nutter there about to top ’imself—and try to take the rest of us with ’im?”

Billy shook his head. “No, we didn’t know. This is my employer. We were just walking to see a customer. Only …”

“Only what, mate? Only what? Look around you—it’s bleedin’ chaos, people’ve been ’urt, look at ’em. Did she know this was going to ’appen? Because if she did, then I’m going over to that copper there and—”

Billy put his arm around Maisie and began to negotiate his way around the rubble, away from the screams of those wounded when a man took his own life in a most terrible way. He looked back into his interrogator’s eyes. “She didn’t know until she saw the bloke. It was when she saw him that she knew.” Maisie allowed herself to be led by Billy, who turned around to the costermonger one last time. “She just knows, you see. She knows.” He fought back tears. “And thanks for helping her, mate.” His voice cracked. “Thanks … for helping her.”

“COME ON IN HERE, bring her in and she can sit down.” The woman called from a shop just a few yards away.

“Thank you, thank you very much.” Billy led Maisie into the shop and to a chair, then turned to the woman. “I’d better get back there, see if there’s any more I can do.”

The woman nodded. “Tell people they can come in here. I’ve got the kettle on. Dreadful, dreadful, what this world’s come to.”

Soon the shop had filled with people while ambulances took the more seriously wounded to hospital. And as she sat clutching a cup of tea in her hands, feeling the soothing heat grow cooler in her grasp, Maisie replayed the scene time and again in her mind. She and Billy crossed the road behind the horse and cart, then ran to the kerb as a motor came along the street. They were talking, noticing people going by or dashing in and out of shops before early closing. Then she saw him, the man, his leg stretched out, as if he were lame. As she had many times before, she reached into her bag to offer money to someone who had so little. She felt the cold coins brush against her fingers, saw the policeman set off across the street, and looked up at the man again—the man whose black aura seemed to grow until it touched her, until she could no longer hear, could not move with her usual speed.

She sipped her now lukewarm tea. That was the point at which she knew. She knew that the man would take his life. But she thought he had a pistol, or even poison. She saw her own hand in front of her, reaching out as if to gentle his wounded mind, then there was nothing. Nothing except a sharp pain at the back of her head and a voice in the distance. Maisie Dobbs … Miss. A voice screaming in panic, a voice coming closer.

“MISS DOBBS?”

Maisie started and almost dropped her cup.

“I’m sorry—I didn’t mean to make you jump—your assistant said you were here.” Detective Inspector Richard Stratton looked down at Maisie, then around the room. The proprietress had brought out as many chairs as she could, and all were taken. Stratton knelt down. “I was on duty at the Yard when it happened, so I was summoned straightaway. By chance I saw Mr. Beale and he said you witnessed the man take his life.” He paused, as if to judge her state of mind. “Are you up to answering some questions?” Stratton spoke with a softness not usually employed when in conversation with Maisie. Their interactions had at times been incendiary, to say the least.

Maisie nodded, aware that she had hardly said a word since the explosion. She cleared her throat. “Yes, of course, Inspector. I’m just a little unsettled—I came down with a bit of a wallop, knocked out for a few moments, I think.”

“Oh, good, you found her, then.” Stratton and Maisie looked toward the door as Billy Beale came back into the shop. “I’ve brought back your document case, Miss. All the papers are inside.”

Maisie nodded. “Thank you, Billy.” She looked up and saw concern etched on Billy’s face, along with a certain resolve. Though it was more than thirteen years past, the war still fingered Billy’s soul, and even though the pain from his wounds had eased, it had not left him in peace. Today’s events would unsettle him, would be like pulling a dressing from a dried cut, rendering his memories fresh and raw.

“Look, my motor car’s outside—let me take you both back to your office. We can talk there.” Stratton stood up to allow Maisie to link her arm through his, and began to lead her to the door. “I know this is not the best time for you, but it’s the best time for us—I’d like to talk to you as soon as we get to your premises, before you forget.”

Maisie stopped and looked up at Stratton. “Forgetting has never been of concern to me, Inspector. It’s the remembering that gives me pause.”

APOLICE CORDON now secured the site of the explosion, and though there were no more searing screams ricocheting around her, onlookers had gathered and police moved in and out of shops, taking names, helping those caught in a disaster while out on Christmas Eve. Maisie did not want to look at the street again, but as she saw people on the edge of the tragedy talking, she imagined them going home to their families and saying, “You will never guess what I saw today,” or “You’ve heard about that nutter with the bomb over on Charlotte Street, well …” And she wondered if she would ever walk down the street again and not feel her feet leave the ground.

DETECTIVE INSPECTOR RICHARD STRATTON and his assistant, Caldwell, pulled up chairs and were seated on the visiting side of Maisie’s desk. Billy had just poured three cups of tea and filled one large enameled tin mug, into which he heaped extra sugar and stirred before setting it in front of his employer.

“All right, Miss?”

Maisie nodded, then clasped the tea as she had in the shop earlier, as if to wring every last drop of warmth from the mug.

“Better watch it, Miss, that’s hot. Don’t want to burn yourself.”

“Yes, of course.” Maisie placed the mug on a manila folder in front of her, and as she released her grip, Billy saw red welts on her hands where heat from the mug had scalded her and she had felt nothing.

“How does your head feel now?” Richard Stratton’s brows furrowed as he leaned forward to place his cup and saucer on the desk, while keeping his eyes on Maisie. The two had met almost three years earlier, when Stratton was called in at the end of a case she had been working on. The policeman, a widower with a young son, had at one point entertained a romantic notion of the investigator, but his approach had been nipped in the bud by Maisie, who was not as adept in her personal life as she was in her professional domain. Now their relationship encompassed only work, though as an observer, it was clear to Billy that Richard Stratton had a particular regard for his employer, despite it being evident that she had brought him to the edge of exasperation at times—not least because her instincts were more finely honed than his own. Regardless, Stratton’s respect for Maisie was reciprocated, and she trusted him.

Maisie reached with her hand to touch the back of her head, a couple of inches above her occipital bone. “There’s a fair-sized bump …” She ran her fingers down to an indentation in her scalp, sustained while she was working as a nurse during the war. The scar was a constant reminder of the shelling that had not only wounded her but eventually taken the life of Simon Lynch, the doctor she had loved. “At least it didn’t open my war wounds.” She shook her head, realising the irony of her words.

“Are you sure you’re up for this?” Stratton enquired, his voice softer.

Caldwell rolled his eyes. “I think we need to get on with it, sir.”

Stratton was about to speak, when Maisie stood up. “Yes, of course, Mr. Caldwell’s right, we should get on.”

Billy looked down at his notebook, the hint of a grin at the edges of his mouth. He knew there was no love lost between Maisie and Caldwell, and her use of “Mr.” instead of “Detective Sergeant” demonstrated that she may have been knocked out, but she was not down.

“I’ll start at the beginning …” Maisie began to pace back and forth, her eyes closed as she recounted the events of the morning, from the time she had placed the cap on her pen, to the point at which the explosion ripped the man’s body apart, and wounded several passers-by.

“Then the bomb—”

“Mills Bomb,” Billy corrected her, absently interrupting as he gazed at the floor watching her feet walk to the window and back again, the deliberate repetitive rhythm of her steps pushing recollections onto centre stage in her mind’s eye.

“Mills Bomb?” Stratton looked at Billy. Maisie stopped walking.

“What?” Billy looked up at each of them in turn.

“You said Mills Bomb. Are you sure it was a Mills Bomb?” Caldwell licked his pencil’s sharp lead, ready to continue recording every word spoken.

“Look, mate, I was a sapper in the war—what do you mean, ‘Are you sure?’ If you go and fire off a round from half a dozen different rifles, I’ll tell you which one’s which. Of course I know a Mills Bomb—dodgy bloody things, saw a few mates pull out the pin and end up blowing themselves up with one of them. Mills Bomb—your basic hand grenade.”

Stratton lifted his hand. “Caldwell, I think we can trust Mr. Beale here.” He turned to Billy. “And it’s not as if it would be difficult for a civilian to obtain such ordnance, I would imagine.”

“You’re right. There’s your souvenir seekers going over to France and coming back with them—a quick walk across any of them French fields and you can fill a basket, I shouldn’t wonder. And people who want something bad enough always find a way, don’t they?”

“And he hadn’t always been a civilian.” Maisie took her seat again. “Unless he’d had an accident in a factory, this man had been a soldier. I was close enough to judge his age—about thirty-five, thirty-six—and his left leg was in a brace, which is why people had to walk around him, because he couldn’t fold it inward. And the right leg might have been amputated.”

“If it wasn’t then, it is now.” Caldwell seemed to smirk as he noted Maisie’s comment.

“If that’s all, Inspector, I think I need to go home. I’m driving down to Kent this evening, and I think I should rest before I get behind the wheel.”

Stratton stood up, followed by Caldwell, who looked at Maisie and was met with an icy gaze. “Of course, Miss Dobbs,” said Stratton. “Look, I would like to discuss this further with you, get more impressions of the man. And of course we’ll be conducting enquiries with other witnesses, though it seems that even though you were not the closest, you remember more about him.”

“I will never forget, Inspector. The man was filled with despair and I would venture to say that he had nothing and no one to live for, and this is the time of year when people yearn for that belonging most.”

Stratton cleared his throat. “Of course.” He shook hands with both Maisie and Billy, wishing them the compliments of the season. Maisie extended her hand to Caldwell in turn, smiling as she said, “And a Merry Christmas to you, Mr. Caldwell.”

MAISIE AND BILLY stood by the window and watched the two men step into the Invicta. The driver closed the passenger door behind them, then took his place and manoeuvred the vehicle in the direction of Charlotte Street, whereupon the bell began to ring and the motor picked up speed toward the site of the explosion. Barely two hours had elapsed since Maisie saw a man activate a hand grenade inside his tattered and stained khaki greatcoat.

Turning to her assistant, she saw the old man inside the young. What age was he now? Probably just a little older than herself, say in his mid-thirties, perhaps thirty-seven? There were times when the Billy who worked for her was still a boy, a Cockney lad with reddish-blond hair half tamed, his smile ready to win the day. Then at other times, the weight of the world on his shoulders, his skin became grey, his hair lifeless, and his lameness—the legacy of a wartime wound—was rendered less manageable. Those were the times when she knew he walked the streets at night, when memories of the war flooded back, and when the suffering endured by his family bore down upon him. The events of today had opened his wounds, just as her own had been rekindled. And instead of the warmth and succour of his family, Billy would encounter only more reason to be concerned for his wife, for their children, and their future. And there was only so much Maisie could do to help them.

“Why don’t you go home now, Billy.” She reached into her purse and pulled out a note. “Buy Doreen some flowers on the way, and some sweets for the boys—it’s Christmas Eve, and you have to look after one another.”

“You don’t need to do that, Miss—look at the bonus, that’s more than enough.”

“Call it danger money, then. Come on, take it and be on your way.”

“And you’ll be all right?”

“I’m much better now, so don’t you worry about me. I’ll be even better when I get on the road to Chelstone. My father will have a roaring fire in the grate, and we’ll have a hearty stew for supper—that’s the best doctoring I know.”

“Right you are, Miss.” Billy pulled on his overcoat, placed his flat cap on his head, and left with a wave and a “Merry Christmas!”

As soon as Maisie heard the front door slam shut when Billy walked out into the wintry afternoon, she made her way along the corridor to the lavatory, her hand held against the wall for support. She clutched her stomach as sickness rose up within her and knew that it was not only the pounding headache and seeing a man kill himself that haunted her, but the sensation that she had been watched. It was as if someone had touched her between her shoulder blades, had applied a cold pressure to her skin. And she could feel it still, as she walked back to the office, as if those icy fingertips were with her even as she moved.

Sitting down at her desk, she picked up the black telephone receiver and placed a telephone call to her father’s house. She hoped he would answer, for Frankie Dobbs remained suspicious of the telephone she’d had installed in his cottage over two years ago. He would approach the telephone, look at it, and cock his head to one side as if unsure of the consequences of answering the call. Then he would lift the receiver after a few seconds had elapsed, hold it a good two inches from his ear and say, with as much authority as he could muster, “Chelstone three-five-double two—is that you, Maisie?” And of course, it was always Maisie, for no one else ever telephoned Frankie Dobbs.

“That you, Maisie?”

“Of course it is, Dad.”

“Soon be on your way, I should imagine. I’ve a nice stew simmering, and the tree’s up, ready for us to decorate.”

“Dad, I’m sorry, I won’t be driving down until tomorrow morning. I’ll leave early and be with you for breakfast.”

“What’s the matter? Are you all right, love?”

She cleared her throat. “Bit of a sore throat. I reckon it’s nothing, but it’s given me a headache and there’s a lot of sickness going round. I’m sure I’ll be all right tomorrow.”

“I’ll miss you.” No matter what he said, when it was into the telephone receiver, Frankie shouted, as if his words needed to reach London with only the amplification his voice could provide. Instead of a soft endearment, it sounded as if he had just given a brusque command.

“You too, Dad. See you tomorrow then.”

MAISIE RESTED FOR a while longer, having dragged her chair in front of the gas fire and turned up the jets to quell her shivering. She placed another telephone call, to the client with whom she and Billy were due to meet this morning, then rested again, hoping the dizziness would subside so that she felt enough confidence in her balance to walk along to Tottenham Court Road and hail a taxi-cab. As she reached for her coat and hat, the bell above the door rang, indicating that a caller had come to the front entrance. She gathered her belongings, and was about to turn off the lights, when she realised that, in the aftermath of today’s events, Billy had forgotten the box of gifts for his family. She turned off the fire, settled her document case on top of the gifts and switched off the lights. Then, balancing the box against her hip, she locked her office and walked with care down the stairs leading to the front door, which she pulled open.

“I thought you might still be here.” Richard Stratton removed his hat as Maisie opened the door.

She turned to go back up to the office. “Oh, more questions so soon?”

He reached forward to take the box, and shook his head. “Oh, no, that’s not it … well, I do have more questions, but that’s not why I’m here. I thought you looked very unwell. You must be concussed—and you should never underestimate a concussion. I left Caldwell in Charlotte Street and came back. Come on, my driver will take you home, however, we’re making a detour via the hospital on the way—to get that head of yours looked at.”

Maisie nodded. “I think you’ve been trying to get my head looked at for some time, Inspector.”

He held open the door of the Invicta for her to step inside the motor car. “At least you weren’t too knocked out to quip, Miss Dobbs.”

As they drove away, Maisie looked through the window behind her, her eyes scanning back and forth across the square, until her headache escalated and she turned to lean back in her seat.

“Forgotten something?”

“No, nothing. It’s nothing.”

Nothing except the feeling between her shoulder blades that had been with her since this morning. It was a sense that someone had seen her reach out to the doomed man, had seen their eyes meet just before he pulled the pin that would ignite the grenade. Now she felt as if that same someone was watching her still.

Stupid, stupid, stupid, foolish man. I should have known, should have sensed he was on the precipice. I never thought the idiot would take his own life. Fool. He should have waited. Had I not told him that we must bide our time? Had I not said, time and again, that we should temper our passion until we were heard, until what I knew gave us currency? Now the only one who knows is the sparrow. An ordinary grey little thing who comes each day for a crumb or two. He knows. He listens to me, waits for me to tell him my plans. And, oh, what plans I have. Then they will all listen. Then they’ll know. I’ve called him Croucher. Little sparrow Croucher,always there, sing-song Croucher, never without a smile. I have a lot to tell him today.

The man closed his diary and set down his pencil. He always used pencil, sharpened with a keen blade each morning and evening, for the sound of a worn lead against paper, the surrounding wood touching the vellum, scraping back and forth for want of sharpening, set his teeth on edge, made him shudder. Sounds were like that. Sounds made their way into your body, crawled along inside your skin. Horses’ hooves on wet cobblestones, cart wheels whining for want of oil, the crackle and snap as the newspaper boy folded the Daily Sketch. Thus he always wrote using a pencil with a long, sharp but soft lead, so he couldn’t hear his words as they formed on the page.

TWO

Faced with advice to go home and rest, and knowing that it would be foolish to embark upon a long drive following a diagnosis of concussion, Maisie revised her plans and decided to travel on the train to Kent that very evening, given that trains would not run to Chelstone on Christmas Day. It would be a surprise for her father, who now did not expect her until Christmas morning. First, though, she wanted to ensure that Billy’s boys received their gifts, so upon arrival back at her flat, she loaded the box into the MG and drove with care across London to Shoreditch. The city was wet, with an unyielding quality of grey light that made the words Merry Christmas seem hardly worth saying. In poorer parts of London, the soup kitchens had been busy, and rations had been distributed to those for whom the festive season was another reminder of what it was to want. Yet in some windows red candles burned a white-gold flame, as the occupants attempted to uplift spirits and reflect the season.

She pulled up outside Billy’s house and was not surprised to see a Christmas tree lit with candles and paper chains framing the window. Silhouettes in the parlour suggested the family was gathered there to decorate the tree. As she walked to the door with the box of gifts, she heard a raised voice coming from the parlour, and wondered if she should not have come.

“Don’t you touch those presents. They’re for Lizzie. I bought them ’specially for a little girl, so don’t you dare touch your sister’s things.”

A child began to cry. Maisie thought it was probably Bobby, the youngest son. She was about to turn away, when she heard Billy, the eldest boy, shout out to his father.

“Miss Dobbs’ motor car’s outside. Quick, let’s have a look at it, Bobby!”

And before she could leave the box of gifts on the step and turn back to the MG, the front door opened.

“Aw, Miss, you shouldn’t’ve gone to all that trouble, what with you not feeling well and all.” Billy stood on the doorstep without a jacket, his shirt collar and tie removed and his sleeves rolled up.

“Is them for us?” Young Billy’s eyes lit up when he saw the packages wrapped in Christmas paper.

“Yes, they’re for you, Billy—and for your brother too! Merry Christmas!”

“Come on in, Miss, and have a cuppa with us before you go.”

“Oh, no, you’re all busy and—”

“Doreen and me won’t hear of it, not after you bringing all this for the boys.” Billy stood back to allow Maisie to come into the passageway, and then opened the door to the parlour. “Doreen, it’s Miss Dobbs.”

Maisie tried to hide her dismay when she saw Doreen Beale standing close to the Christmas tree, clutching a child’s threadbare toy lamb to her heart. Her hair was drawn back, which accentuated sallow skin that had sunk into her face, and cheekbones that seemed to jut out from under her eyes. The cardigan she was wearing was soiled at the cuffs and her dress had some dried food on the front. Though Billy and his wife were working hard to put money by for passage to Canada, and what they hoped would be a new life, they were proud people, and Doreen was especially meticulous when it came to keeping the family’s clothing clean and pressed, no matter how old it might be, or how many owners it might have had before.

“It’s lovely to see you, Doreen.” Maisie approached her and placed her hand on the woman’s arm. “How are you keeping?”

She looked at Maisie’s hand as if she could not quite fathom who this visitor might be, and how her arm had become thus burdened. Then, her eyes filling with tears, she beamed a smile filled with hope. “Have you brought a present for my little girl? She loves her dolls, you know, and her lamb. Did you bring her something?”

Maisie looked around at Billy, who set the box of gifts under the tree, and came to his wife, placed his arm around her and began to lead her to the kitchen.

“Let’s go and put the kettle on for Miss Dobbs, eh, Doreen? Let’s have a nice cup of tea, then we can all sit down and look at the tree.”

“All right, Billy. I’ll be better when I’ve had a cup of tea.”

Billy returned to the parlour. Now that he was not wearing his jacket, as he did at all times in the office, Maisie realised that he too had lost weight.

“Sorry, Miss, she’s having a bit of a turn. All the excitement of putting up the tree, I suppose. And—as you know—it’s coming up to a year ago that we lost our little Lizzie. Apparently, it does this sort of thing, an anniversary.”

Maisie wanted to ask questions, wanted to know how she might be able to help, but this was Christmas, and she knew Billy would want to settle his children and his wife, so the family might have a calm day tomorrow.

“I’d better be off, Billy. I’ve got to get down to Kent, and I’m taking the train—don’t want to drive down, not with this bump on the back of my head.”

“Oh, Miss, and you drove over here for us.” He turned to his boys, who were silent and watching, and as Maisie could see, were fully aware of their mother’s plight. “What do you say to Miss Dobbs?”

They echoed thanks, and Maisie said they could each sit in the driver’s seat of the MG for a minute or two, then she had to leave. And as she drove away, Maisie looked back and saw Billy standing on the doorstep, one boy held to him, the other clutching his hand. The children waved and then the three turned and went inside the house.

December 26th, 1931

Christmas Day had passed with a mellow quietness, as Maisie and her father spent time by the fire, sometimes talking, sometimes reading, with her father’s dog, a lurcher known as Jook, temporarily changing allegiance to sit at her feet. They shared a hearty festive meal of roast capon and all the trimmings, and enjoyed a short walk across fields whitened by ground frost, the length of the stroll dictated by Frankie’s years and her lingering concussion, which, though subsiding, still caused some dizziness if she remained on her feet too long.

Maisie had planned a return to London early on the morning of December 27th, taking Boxing Day off to further recuperate and enjoy her father’s company. She had arrived at Chelstone railway station late on Christmas Eve, and was collected at the station by the estate’s chauffeur, who had been released to do so by her father’s employer, Lady Rowan Compton, who was delighted to know that Maisie would be returning for the holiday. Lady Rowan held a special affection for Maisie and had played a part in her rise from a lowly position on the household staff to the professional woman she was today. For his part, Frankie Dobbs had been relieved to have his daughter home on Christmas Eve, and felt all was well as they dressed the Christmas tree together and placed their gifts underneath, as they had done when Maisie was a child.

Now, waking on Boxing Day morning, Maisie reached for the small clock next to her bed. It was six o’clock. Her father was already downstairs pottering in his kitchen and talking to Jook as he prepared breakfast. For once, Maisie did not scramble out of bed to go to the kitchen, though she loved to share in the cosy warmth while sitting at the table in front of the black cast-iron stove that seemed to push out enough heat to drive a train. She had always enjoyed this time in the morning with her father, when the tea was strong in the pot, the hearth welcoming and the sizzle of bacon and eggs tempting her senses. But today she wanted only to listen to the morning sounds—a solitary bird outside singing despite winter’s onslaught and the wind against the glass panes. She closed her eyes and must have fallen asleep again, for it was the shrill ring of the telephone that woke her. She heard her father complain, heard his steps along the red flagstones that led from the kitchen to the sitting room, and heard the telephone continue to ring while he considered who it might be.

Picking up the receiver and without first reciting his telephone number, Frankie shouted, “What do you want?” and then was quiet. Maisie sat up in bed, waiting.

“Well, she’s not well, Inspector. Caught a bit of a throat and hasn’t been feeling her usual self, you know.” Silence again. “All right, all right, you wait here and I’ll get her for you.”

Maisie leapt from her bed and reached for her woollen dressing gown hanging on a hook behind the door. “I’m coming, Dad.”

She ran downstairs and straight into the sitting room, where she smiled at her father as she took the receiver from his hand. “Yes, this is Maisie Dobbs.”

“Miss Dobbs. Richard Stratton here. Sorry to bother you at home.”

“How did you find me?” She paused. “Stupid question, Inspector. How can I help you—and on Boxing Day?”

“We have a situation of some urgency and importance on our hands. I would like you to come to the Yard as soon as you can.”

“Well, I was planning to come back to London tomorrow on the train—I decided not to drive after all.” She looked around to see whether her father was in earshot, then turned her back on the kitchen. “And thank you for not saying anything to my father about the incident on Christmas Eve. I can’t have him worrying.”

“Of course, I understood the situation. Now then, can you return today? I can have a motor car at your door by eight.”

“That’s certainly urgent.”

“I wouldn’t ask if it was not critical. We need to draw upon all resources, Miss Dobbs, and in this case, I believe you are a most valuable resource.”

“I’ll be ready at eight.”

“Thank you. I will brief you on our return to London.”

“Until then.” Maisie frowned when she realised that Stratton would himself be coming to collect her. She set down the receiver and walked into her father’s kitchen. Jook rose from her place alongside the stove and came to Maisie, nudging her hand with a welcoming wet nose.

“Dad, I’m sorry about this, but I’ve got to go back to London.”

“I thought as much. You don’t get these Scotland Yard blokes making telephone calls early on a Boxing Day morning for nothing.” He paused, taking a frying pan from the stove and slipping two eggs and a rasher of bacon on a plate. “I’ve had mine, but you can’t be shooting off up there without a good breakfast inside you, so get stuck into that. We can at least sit together for a while until you’ve to leave.”

Maisie sat at the table and as she began to eat, her father filled two mugs with tea, set one in front of her and seated himself opposite his daughter.

“You know, I don’t hanker after the Smoke at all.” Frankie shook his head and shrugged. “I thought I would when I first came down to Chelstone, in the war. But aside from sometimes missing the market, you know, a bit of banter, the companionship of it all, I don’t miss London. Not one bit. Last time I went up there to see you, it’d changed too much for my liking. I couldn’t believe the racket. I mean, when I was boy, you had your noise, but not like now, not with all them motors and lorries and the horses and carts vying for a bit of road. And when you go into a shop, there’s tills with bells, them adding and typewriting machines in the background when you’re at the bank. Can’t hear yourself think. And now it’s full of people out of work. Then, of course, there’s them who’ve got too much—mind you, that’s always been the way. But it seems, oh, I dunno—a desperate sort of place to me.”

Maisie stopped eating for a moment and regarded her father. It was at times like this that he surprised her most. He often began such proclamations with the words, “I’m an ordinary bloke, but …” And on such occasions, Maisie found him far from ordinary.

“Yes, it’s a desperate place for a lot of people, Dad. And the irony of it is that it means, in many cases, someone like me stays in business.”

Frankie nodded. “That’s what worries me. And Detective Inspectors who know where to find you and ring early on a Boxing Day morning. Desperate, I would say.”

Maisie changed the subject, though she knew Frankie was more than aware of her conversational manoeuvre. He would take her lead and speak of this and that, of minor goings-on at Chelstone Manor, anything except the fact that soon his beloved daughter would be collected by a senior Scotland Yard detective because something untoward had happened in what he considered to be a desperate sort of place.

“HERE’S THE SITUATION.” Stratton turned to Maisie as the driver negotiated the narrow country lanes that led from Chelstone to Tonbridge and then on to the main London road. “A threat has been received by the Home Secretary and is now in the hands of Scotland Yard. I am one of three senior officers designated to deal with the situation. Seeing as the threat pertains to what amounts to murder, I was called in immediately.”

“What sort of threat is it?”

“That’s just it, it hasn’t been spelled out, just the consequence. A letter was received at Westminster—you’ll see it later—plain vellum, no postmark, no prints, no distinguishing marks at all, the handwriting could have come from anyone, though we have an expert looking at it, obviously.”

“But there are demands.”

“Yes. The man—or woman—is asking the government to act immediately to alleviate the suffering of all unemployed, starting with measures to assist those who have served their country in wartime. There’s a bit of a rant about what they did for their country and now look at them, and there’s a threat to the effect that, if no action is forthcoming within forty-eight hours—which will be up tomorrow morning—then he will demonstrate his power. We have to entertain the possibility that such a threat may be to the life of the Home Secretary, the Prime Minister, or another important person.”

“And what about the possibility of a hoax, or some disenfranchised individual letting off steam?”

“As you know, Miss Dobbs, some of those disenfranchised people can be dangerous—take the Irish situation, the Fascists, the unions. There are a lot of holes in which this particular rodent might be concealing himself.”

“Yes, of course.” Maisie paused, looking out of the window as she considered Stratton’s synopsis of the situation. She turned back to Stratton. “Look, I must ask you this, especially as I am now travelling back to London when I could have spent the day with my father—but what has this got to do with me? You have senior detectives working on the case—how can I help?”

“I can think of several different ways in which you can help, Miss Dobbs, and the talents that might render you a valuable member of the group. Certainly you are known at the Yard, and your contribution to the training of our women detectives has not gone unnoticed. But the fact is that your presence has been”—he slowed his speech, as if choosing his words with care—“requested, because whoever is behind the threats has mentioned you by name. ‘If you doubt my sincerity, ask Maisie Dobbs.’ That’s what he said. So, whether you like it or not, you are part of this case. And unfortunately, the first thing you will have to do is submit to questioning.”

Maisie shook her head. “So that’s why you’re accompanying me to Scotland Yard, to bring me in for questioning. I’m a suspect. I wish you had been honest at the outset.”

“It’s not quite like that, Miss Dobbs.” Stratton took a deep breath. “On the one hand, we know who you are, we know your reputation. But at the same time we need to ensure that you are on our side before we go any further, especially as there’s a suspicion that you may be implicated in some way.” He paused. “And there’s one more thing: Special Branch is taking care of this one.”

“I should have guessed. And how are you connected to Special Branch?”

Stratton turned to look at Maisie directly. “Let’s just say I’m moving in that direction. Detective Chief Superintendent Robert MacFarlane is leading the enquiry. And it’s on the cards that I’ll be reporting to him by Easter—leaving the Murder Squad and joining Special Branch—and that information is a bit hush-hush.”

“Congratulations, Inspector Stratton.” She wiped a hand across condensation inside the window and looked out at the frost-covered landscape for a moment. “Tell me more about MacFarlane—‘Big Robbie’ has a reputation that goes before him. Maurice Blanche has worked with him, and he came to talk to us when I was studying at the Department of Legal Medicine in Edinburgh.” Maisie smiled and shrugged. “To tell you the truth, I liked him. I had a sense that you knew where you stood with MacFarlane—though I’ll be honest, I thought he was a bit of a one with the ladies.”

Stratton gave a half laugh. “Oh yes, and probably more so since his wife left him a couple of years ago. But there’s no doubt, you know where you are with Robbie, all right. He’s fair, speaks his mind, and gives his people the leeway they need to get the job done. Mind you, at the same time, he expects every ounce of you on the case.”

“Well, I look forward to meeting him again. I wonder if he remembers me.”

“Yes, he remembers you, Miss Dobbs. That’s another reason why you were summoned at an unearthly hour on Boxing Day morning.”

MAISIE’S FIRST VISIT to New Scotland Yard, on the Embankment, had taken place when she was working with Maurice Blanche as his assistant. She found the grand red-brick building intimidating, with its ornate chimneys, projecting gables and turrets at each corner. In the intervening years, she had come to take visits to “the Yard” in her stride. Today, though, she was escorted to the area of Scotland Yard occupied by Special Branch, and led into a sparsely decorated room, where she waited while Stratton left to inform others involved in the investigation that they had arrived. Soon she heard a voice booming down the corridor, but when Robert MacFarlane walked into the room with Stratton, the timbre was lower, with a soft Scottish burr belying his position, and the situation. Maisie rose from her chair and extended her hand in greeting.

“Miss Dobbs, thank you for coming.” The Detective Chief Superintendent shook her hand, then nodded toward the chair. “Sit down, lass, sit down. I trust your father was not too upset by your sudden departure from the family hearth.”

“He understands the nature of my work.”

“Good, I’m glad one of us does.” Taking his seat behind a wooden desk that seemed too small to accommodate his height—MacFarlane was well over six feet tall and, thought Maisie, had the frame of a docker. He was about fifty-five years of age, light of foot and precise in his movements. A track of baldness revealed a scar where a stray bullet had nicked him in the war—the fact that he had simply wiped blood away and sworn at the enemy for putting a hole in his tam o’shanter was the stuff of legend—and the cropped hair that flanked his shining pate was gunmetal grey and controlled with a whisper of oil.

“Stratton, bring in Darby, if you wouldn’t mind.”

Soon the four were seated: Maisie, MacFarlane, Stratton and Colm Darby, a man who had worked alongside MacFarlane since before the war and, when the policeman returned from France, joined him once more. Darby was probably a good five years older than his superior. Maisie knew him to be an expert in the analysis of personal markers left behind by the perpetrator of a crime. The nature of one’s handwriting was an area in which he was said to have great insight. He had been with MacFarlane since the days when the main roles of the department encompassed intelligence and security to protect the country from extremist activity known as the “Irish problem.” Now Special Branch had a broader role, and it seemed as if Colm Darby might never retire. MacFarlane introduced Maisie, then leaned forward so that his forearms rested on the desk.

“Miss Dobbs, I am dispensing with protocol here—because I can, and because I believe we have no time to lose.” He sighed, looking directly into Maisie’s eyes. “I know Maurice Blanche, I’ve worked with him in the past, and I remember you from Edinburgh—Blanche sent you there, I understand.”

“Yes, that’s correct, in preparation for my work with him, when I was his assistant.”

MacFarlane looked down at an open manila folder, flipped over a page of notes, then closed the folder before resuming eye contact with Maisie. “Now, first of all, in your own words, describe the events of Christmas Eve.”

Maisie drew breath and, as she had for Stratton before, described approaching the man on Charlotte Street, and witnessing him take his life with a Mills Bomb.

“Not a pretty sight, I’m sure.”

“I’ve seen some ugly sights in my time, Chief Inspector.”

“I bet you have, Miss Dobbs. And we don’t, any of us, want to be seeing any more, though I imagine that might be a wee bit of a faint hope.” MacFarlane cleared his throat. “Can you explain how a man who has made veiled threats that amount to a risk to our country’s security might know the name of a little wee lassie like yourself?”

Maisie bristled, but checked herself, aware that the goading was deliberate, though she knew that, in the circumstances, she might have employed the same tactic herself. She leaned forward, mirroring MacFarlane’s position. Darby looked at Stratton, and raised an eyebrow.

“Chief Inspector, to be perfectly honest with you, at this juncture I have no idea why I was mentioned in such a letter. However, your line of questioning regarding the tragedy I witnessed on Christmas Eve would indicate that you see a relationship between the two events, and I am inclined to veer in that initial direction myself.” She turned to face Stratton and Darby, bringing them into the conversation. “I was the closest person to the victim to walk away without significant physical injury—and yes, I see him as a victim. So if—if—there was an associate of the dead man nearby, I would have been seen. If the two cases are linked, the person who wrote the letter could be that same individual, perhaps using my name as leverage to give some kind of weight to his endeavor. It might also be a means of subverting your attention, of course.”

MacFarlane leaned back in his chair, as did Maisie in hers. The policeman smiled. “Just like bloody Blanche! I move, you move, I do this, you do the same thing. It’s like being followed.” He shook his head. “Look, Miss Dobbs, I know—know, mind—that you haven’t anything to do with this tyke, but you might have had some brief contact with him, you might have seen him, or he might have an interest in you.” He brushed his hand across his forehead. “I know this could be the work of a bit of a joker, but my nose tells me this boy is serious, that he means what he says. Now then, we can play a waiting game, see what happens next, or we can start looking. I favour action, which is why I’ve asked you here. You’re involved in this whether you like it or not, Miss Dobbs, and I would rather have you under my nose working for me than anywhere else.”

“I’m used to working alone, Chief Inspector.”

“Well, for now you can get un-used to it. First of all, let me apprise you of the work of Special Branch. Even though I am sure you have some familiarity, if you are going to be reporting to me, then I want to start us off on the right foot. So, a little lesson, and I’ll make it snappy. The Special Branch is, technically, part of the Criminal Investigation Department, but as you may have heard we like to go about our business in our own fashion. Suffice it to say that we only answer questions when the person asking has a lot of silver on the epaulettes, or around the peak of his cap. Our normal work is in connection with the protection of royalty, ministers and ex-ministers of the Crown, and foreign dignitaries. We also control aliens entering our country. We are responsible for investigation into acts of terrorism and anarchy, and to that end have a lot of people to keep an eye on. Before I go on, I should add—mainly because I can see a bit of a problem looming here—that on occasion we cross paths with Military Intelligence, Section Five, for obvious reasons. We try to get along, and they need us, mainly because we have powers of arrest. There, now I can take off my professoring hat and get down to business. Do you have any questions?”

“No, sir.”