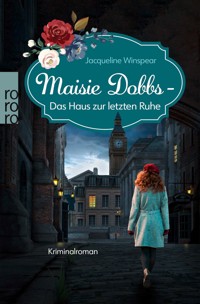

9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Maisie Dobbs

- Sprache: Englisch

Britain is at war. Returned from a dangerous mission onto enemy soil and having encountered an old enemy and the Führer himself along the way, Maisie Dobbs is fully aware of the gravity of the current situation and how her world is on the cusp of great change. One of those changes can be seen in the floods of refugees that are arriving in Britain, desperate for sanctuary from the approaching storm of war. When Maisie stumbles on the deaths of refugees who may have been more than ordinary people, she is drawn into an investigation that requires all her insight and strength.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 512

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

IN THIS GRAVE HOUR

A Maisie Dobbs Novel

JACQUELINE WINSPEAR

Dedicated to Irene, Joyce, Sylvia, Joseph, Ruby, Charles, and Rose Our family’s World War II evacuees

In this grave hour, perhaps the most fateful in our history … for the second time in the lives of most of us, we are at war.

– KING GEORGE VI, 3RD SEPTEMBER 1939

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

London, Sunday 3rd September 1939

Maisie Dobbs left her garden flat in Holland Park, taking care to lock the door to her private entrance as she departed. She carried no handbag, no money, but had drawn a cardigan around her shoulders and carried a rolled umbrella, just in case. There had been a run of hot summer days punctuated by intermittent storms and pouring rain, leaving the air thick and clammy with the promise of more changeable weather, as clouds of luminous white and thunderous graphite lumbered across the sky above. They reminded Maisie of elephants on the march across a parched plain, and in that moment she wished she were far away in a place where such beasts roamed.

Her journey was short – just a five-minute walk along a leafy street towards a Georgian mansion of several stories: the home of her oldest friend, Priscilla Partridge, along with her husband, Douglas, and their three sons. The youngest, Tarquin, had been sent to Maisie’s flat earlier with a message for her to hurry, so they could listen to the wireless together – as family, united, at the worst of times. For without doubt, Maisie was considered family as far as Priscilla, her husband, and their boys were concerned.

Despite the warmth of the day, Maisie felt chilled in her light summer dress. She slipped her arms into the sleeves of her cardigan as she walked, transferring the umbrella from one hand to the other, conscious of every movement.

Where was she the last time? Had she been so young, so distracted by her new life at Girton College, that she could not remember where she was and what she had been doing when the news came? She stopped for a moment. It had been another long, hot summer then – the perfect English summer, they’d said – and she wondered if, indeed, weather had something to do with the outcome, pressing down on people, firing the tempers of powerful men until they reached a point of no return, spilling over to upend the world.

The mansion’s front door was open before she set foot on the bottom step.

‘Tante Maisie, come, you’ll miss it.’ Thomas, now eighteen years of age, stood tall, his hair just a shade lighter than his mother’s coppery brown. He was smiling as he beckoned Maisie to hurry, then held out his hand to take hers. ‘The wireless is on in the drawing room, and everyone’s waiting.’

Maisie nodded. It seemed to her that each day Priscilla’s boys gained inches in height and increased their already boundless energy. And though he was the eldest, Thomas could still engage in rambunctious play with his brothers. They’d always reminded Maisie of a basket of puppies on those occasions when she saw them in the garden, teasing one another, tugging on each other’s hair or the scruff of the neck. But Thomas was also a man. Today, of all days, his passing boyhood filled her with dread.

‘Maisie – come on!’ Priscilla hurried into the entrance hall, brandishing a cigarette in a long holder. She reached out and linked her arm through Maisie’s. ‘Let’s get settled.’

As they stepped into the drawing room, Douglas Partridge managed a brief smile and a nod as he approached. ‘Maisie. Good, you’re here.’ He drew back after touching his cheek to hers, and held her gaze for a second. Each saw the pain in the other, and the effort to press back the past. She nodded her understanding. Memories seemed to collide with the present as they joined Priscilla and the boys, along with the household staff – a cook, housekeeper, and Elinor, the family’s long-serving nanny, no longer needed but much loved.

‘I thought we should all be together,’ said Priscilla as the housekeeper moved to pour more tea. The wireless crackled, and the company grew silent. Priscilla shook her head – no, no more tea – and motioned for the housekeeper to take a seat, but she remained standing, a hand on the table as if to keep herself steady.

Douglas reached towards the set to adjust the volume.

‘Here we go,’ he said.

Maisie noticed Douglas glance at his watch – he wore it on his right wrist, given the loss of his left arm during the Great War – and was aware that she and Priscilla had cast their eyes towards the clock on the mantelpiece at exactly the same moment, and Timothy had leant across, lifted his older brother’s wrist and looked at the dial on his watch, touching it as if to embed the moment in his memory. It was eleven-fourteen on the morning of 3rd September 1939.

The wireless crackled again: static signalling the coming storms. At quarter past eleven, the voice they had gathered to hear – the clipped tones of Neville Chamberlain, the Prime Minister – shattered their now-silent waiting.

This morning the British Ambassador in Berlin handed the German Government a final note stating that, unless we heard from them by 11 o’clock that they were prepared at once to withdraw their troops from Poland, a state of war would exist between us.

I have to tell you now that no such undertaking has been received, and that consequently this country is at war with Germany.

As the speech continued, all present stared at the wireless as though it held the image of a person. Maisie felt numb. It was as if the cold, slick air of France had remained with her since the war – when, she wondered, would they begin referring to it as ‘the last war’? – and now the terrible, biting chill was seeping out from its place of seclusion deep in her bones. She glanced at Priscilla, and saw her friend staring at her sons, each one in turn as if she feared she might forget their faces. And she knew the deep ache of loss was allowing Priscilla no quarter – the dragon of memory that war had left in its wake; a slumbering giant stretching into the present, starting anew to breathe fire again. Priscilla’s three brothers had perished between the years 1914 and 1918.

Now may God bless you all. May He defend the right. It is the evil things that we shall be fighting against – brute force, bad faith, injustice, oppression and persecution – and against them I am certain that the right will prevail.

Douglas, who had remained standing throughout the speech, leant forward to switch off the wireless.

Priscilla touched the housekeeper on the shoulder and asked for a pot of coffee to be brought to the drawing room. The cook had already returned to the kitchen, reaching for her handkerchief and dabbing her eyes as she closed the door behind her. Elinor had followed with a muttered explanation that she ‘had to see to something’; no one heard what it was that had to be seen to.

‘Papa … what do you think of—’

‘Father, Mother, I think I should—’

‘Maman, shall we—’

The boys spoke at once, but fell silent when Douglas raised his hand. ‘It’s time we men went for an invigorating, excitement-reducing walk around the park just in case the day spoils and the rain really comes down. Come on.’ And with that, all three of Priscilla’s sons left the room, ushered away by their father, who held up his cane as if it were the wing of a hen chivvying along her chicks.

Silence seemed to bear down on the room as the door closed.

Priscilla’s eyes were wide, red-rimmed. ‘I’m not going to lose my sons, Maisie. If I have to chop off their fingers to render them physically unacceptable to the fighting force, I will do so.’

‘No, you won’t, Pris.’ Maisie came to her feet and put an arm around her friend, who was seated next to the wireless. She felt Priscilla lean in to her waist as she stood beside her. ‘You wouldn’t harm a single hair on their heads.’

‘We came through it, didn’t we, Maisie?’ said Priscilla. ‘We might not have been unblemished on the other side, but we came through.’

‘And we shall again,’ said Maisie. ‘We’re made of strong fabric, all of us.’

Priscilla nodded, pulling a handkerchief from her cuff and dabbing her eyes. ‘We Everndens – and never let it be forgotten that in my bones I am an Evernden – are better than the Herr-bloody-Hitlers of this world. I’d chase him down myself to protect my boys.’

‘You’re one of the strongest, Priscilla – and remember, Douglas is worried sick too. You’re a devoted family. Hold tight.’

‘We’re all going to have to hold tight, aren’t we?’

Maisie was about to speak again when there was a gentle knock at the door, as if someone had rubbed a knuckle against the wood rather than rapping upon it.

‘Yes?’ invited Priscilla.

The housekeeper entered and announced that there was a telephone call for Maisie, though she referred to her by her title, which was somewhat grander than plain Miss Dobbs.

Maisie gave a half smile. ‘Who on earth knows I’m here?’ she asked, without expecting an answer.

‘Well, your father would make a pretty good guess and come up with our house, if you weren’t at home. I daresay they’ve been listening to the wireless too, and Brenda would have wanted him to call. You’ll probably hear from Lady Rowan soon too.’

‘Oh dear,’ said Maisie as she stepped towards the door. ‘I do hope Dad’s all right.’

In the hall, she picked up the telephone receiver, which was resting on a marble-topped table decorated with a vase of blue hydrangeas.

‘Hello. This is Maisie Dobbs. Who’s speaking, please?’

‘Maisie, Francesca Thomas here.’

Maisie put her hand across the mouthpiece and looked around. She was alone. ‘Dr Thomas, what on earth is going on? How do you know this number? Or that I would be here?’

‘Please return to your flat, if you don’t mind. I have some urgent business to discuss with you.’

Maisie felt a second’s imbalance, as if she had knelt down to retrieve something from the floor, and had come to her feet too quickly. What was the urgent business that this woman – someone in whose presence she had always felt unsettled – wanted to discuss on a Sunday, and in the wake of the Prime Minister’s broadcast to the nation?

Francesca Thomas had spent almost her entire adult life working in the shadows. In the Great War she had become a member of La Dame Blanche, the Belgian resistance movement comprised almost entirely of girls and women who had taken up the work of their menfolk when they went to war. Maisie knew that with her British and Belgian background, Thomas was now working for the Secret Service.

‘Dr Thomas, I am not interested. Working with the—’ She looked around again and lowered her voice. ‘Working with your department is not my bailiwick. I am not cut from that sort of cloth. I told Mr Huntley, quite clearly, no more of those assignments. I am a psychologist and an investigator – that is my domain.’

‘Then you are just the person I need.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘Murder, Maisie. And I need you to prevent it happening again. And again.’

‘Where are you?’

‘In your flat. I took the liberty – I hope you don’t mind.’

CHAPTER ONE

As Maisie hurried from Priscilla’s house, fuming that Francesca Thomas had violated her privacy by breaking into her flat – a criminal act, no less – an angry, deep-throated mechanical baying seemed to fill the air around her. It began slowly, gaining momentum until it reached full cry. A woman in a neighbouring house rushed into the front garden to pull her children back indoors. A man and woman walking a dog broke into a run, gaining cover in the lee of a wall. There were few people out on this Sunday morning – indeed, many had remained indoors to listen to the wireless – but those on the street began to move as quickly as they could. Maisie watched as each person reached what they thought would be a place of safety – running towards the sandbagged underground station, to their homes, or even into a stranger’s doorway. Shielding her eyes from the sun, she looked up into the sky. Nothing more threatening than intermittent clouds. No bombers, no Luftwaffe flying overhead. It was just a test. A test of the air-raid sirens situated across London. She looked at her watch. Twenty to twelve now. People began to emerge from their hiding places, having realised there were no metal-clad birds of prey ready to swoop down on life across the city. It was nothing more than practise – as if they needed practise for war.

Taking the path at the side of the property, Maisie approached her flat by the garden entrance. Dr Francesca Thomas was seated on a wicker chair set on the lawn. She was smoking a cigarette, flicking ash onto the grass at her feet. The French doors were open to the warmth of the day, and Thomas leant back as if to allow a beam of sunlight to bathe her face. Maisie studied her for a few seconds. Thomas was a tall woman, well dressed in a matching costume of skirt and jacket, the collar of a silk blouse just visible and the customary scarf tied around her neck, the ends poked into the V of the blouse, as a man might tie a cravat. The scarf was scarlet, and Maisie suspected that if it were opened up and laid flat, a pattern of roses would be revealed. Her thick hair, now threaded with grey, was cut above the shoulder and brushed away from her face. It was a strong face, thought Maisie, with defined black eyebrows, deep-set eyes, and pale skin. She wore a little rouge on her cheeks, and lipstick that matched the scarf.

Francesca Thomas did not look up as Maisie approached. Her eyes remained closed as she began to speak.

‘Lovely garden you have here, Maisie. Quite the sun trap. Those hydrangeas are wonderful.’

Maisie sat down in the wicker chair next to her visitor. ‘Dr Thomas – Francesca – you didn’t come here to talk to me about the hydrangeas. So, shall we go inside and you can tell me what was so important that you had to break into my house and hunt me down.’

Thomas shielded her eyes with her hand. ‘Yes, let’s go in.’

Maisie came to her feet and extended her hand, indicating that Thomas should enter the flat first. She paused briefly to look at the French doors. They appeared untouched, though no key had been used to open them.

‘I won’t ask how you broke in, Francesca – but I will get all my locks changed now.’

‘Never mind – most people wouldn’t have been able to break into the flat. I’m just a bit more experienced. Now then, let’s get down to business.’

The doors to the garden remained open. Francesca Thomas made herself comfortable on the plump chintz-covered sofa set perpendicular to the fireplace, while Maisie took a seat on the armchair facing her.

‘Maisie,’ Thomas began, ‘you will remember that during the last war many, many refugees from Belgium flooded into Britain.’

Maisie nodded. How could she forget? Over a quarter of a million people had entered the country, fleeing the approaching German army, the terror of bombing and occupation. Most had lost everything except the clothes they stood up in – homes, loved ones, neighbours, and their way of life – everything they owned left behind in the struggle.

‘At one point, over sixteen thousand people were landing in the coastal ports every single day,’ Thomas continued. ‘From Hull to Harwich, and on down to Folkestone. It went on for months.’

‘And yet after the war, they left so little behind,’ said Maisie. ‘When they left, they might never have been here in England – isn’t that true?’

‘Yes. They were taken in, and in some areas there were even new towns built to house them – they had their shops, their currency. And after the Armistice, Britain wanted the refugees out, and their own boys home.’

‘And I am sure the Belgian people had a desire to return to their country too.’

‘Of course they did. They wanted to start again, to rebuild their communities and their lives.’

‘But some stayed,’ said Maisie.

‘Yes, some stayed.’ Thomas nodded, staring into the garden.

Maisie noticed that Francesca Thomas had not said ‘we’ when referring to the Belgians, and she wondered how the woman felt now about the heritage she had claimed during the war. In truth she was as much British as she was Belgian. Maisie wondered if in serving the latter she had mined a strength she had not known before, just as Maisie had herself discovered more about her own character in wartime. She rubbed a hand across her forehead, a gesture that made Thomas look up, and resume speaking.

‘There are estimates that up to seven or eight thousand remained after the war – they had integrated into life here, had married locally, taken on jobs, changed their names if it suited them. They didn’t stand out, so there was an … an integration, I suppose you could say.’ Thomas gave a wry smile.

‘But life is not easy for any refugee,’ said Maisie.

‘Indeed. They went from being welcomed as the representatives of “poor little Belgium” to their hosts wondering when they would be leaving – and often quite vocal about it. And although there were those villages set up, they were not places of comfort or acceptance in the longer term. But as I said – most refugees went home following the war.’

‘Tell me what all this has to do with me, and how you believe I can help you.’

Thomas nodded. ‘Forgive me, Maisie – I am very tired. There has been much to do in my world, as I am sure you might understand. I begin to speak about the war, and a wash of fatigue seems to drain me.’

Maisie leant forward. Such candor was not something she had experienced in her dealings with Thomas. She remembered training with her last year, before her assignment in Munich. Thomas had drilled her until she thought she might scream ‘No more!’ – but the woman had done what she set out to do, which was to make sure Maisie had the tools to ensure her own safety, and that of the man she had been tasked with bringing out of Munich under the noses of the Nazis. Now it was as if this new war was already winning the battle of bringing Thomas down.

‘I want you to do a job of work for me, Maisie. This is what has happened. About a month ago, the fourth of August, a man named Frederick Addens was found dead close to St Pancras Station. He had been shot – point-blank – through the back of the head. The position in which he was found, together with the post-mortem, suggested that he was made to kneel down, hands behind his head, and then he was executed.’

‘So he could well have seen his killer,’ said Maisie. ‘It has all the hallmarks of a professional assassination.’

‘I suspect that is the case.’

‘Tell me about Addens,’ said Maisie.

‘Thirty-eight years of age. He worked for the railway as an engineer at the station. He was married to an English woman, and they have two children, both adults now and working. The daughter is a junior librarian – she’s eighteen years of age, and the son – who’s almost twenty – has now, I am informed, joined the army.’

Maisie nodded. ‘What does Scotland Yard say?’

‘Nothing. War might have been declared today, but it broke out a long time ago, as you know. Scotland Yard has its hands full – a country on the move provides a lot of work for the police.’

‘But they are investigating, of course.’

‘Yes, Maisie, they are investigating. But the detective in charge says that it is not a priority at the moment – it’s what they call an open-and-shut case because they maintain it was a theft and there were no witnesses, therefore not much to go on – apparently there was no money on Addens when his body was discovered, and no wallet was found among his belongings at the station. And according to Scotland Yard, there are not enough men on the ground to delve into the investigation.’

‘What’s his name?’ asked Maisie.

‘Caldwell. Do you know him?’

‘Yes. I know him – though we’ve not crossed paths in a few years.’ Maisie paused. ‘What about Huntley’s department, or the Foreign Office? Surely they must be interested in the outcome of this one.’

‘Chinese walls and too much to do – you know how it is, Maisie.’ Francesca Thomas came to her feet and stood by the door, her gaze directed towards the garden. ‘I want you to investigate for me. I trust you. I trust you to keep a calm head, to be diligent in your work, and to come up with some answers.’

‘I don’t do this kind of work for nothing, Dr Thomas.’ Maisie stepped towards the bureau in the corner, took a sheet of paper and pen, and wrote down a series of numbers. She handed it to Thomas. ‘These are my fees, plus I will give you a chit to account for costs incurred along the way.’

Thomas looked at the paper, folded it, and put it in her pocket. ‘I will issue you with an advance via messenger tomorrow, and I will also send you addresses, employment details, and any other information I have to hand on Addens. I take it you will start immediately.’

‘Of course.’ Maisie allowed a few seconds to pass. ‘Dr Thomas – Francesca—’ She spoke the woman’s name in a quiet voice, so that when Thomas turned it was to look straight into Maisie’s eyes. ‘Francesca, are you telling me everything?’

‘A Belgian refugee – one of my countrymen – who made England his home and lived in peace here, is dead. The manner of his death begs many questions, and I want to know who killed him. That is the nub of the matter.’

Maisie nodded. ‘I will expect your messenger tomorrow – at my office in Fitzroy Square.’

Francesca Thomas picked up the clutch bag she had set upon the sofa. ‘Thank you, Maisie. I knew I could depend upon you.’ She left by the French doors; seconds later Maisie heard the gate at the side of the house clang shut.

She stepped into the walled garden. Beyond the brick terrace and lawn, she’d planted a perennial border to provide colour from spring to autumn. The hydrangeas admired by Thomas had grown tall and covered the walls, their colour reflected in an abundance of Michaelmas daisies. She strolled the perimeter of the garden, deadheading the last of the season’s roses as she went. This was ground she knew well – investigating a death in suspicious circumstances was home turf. But two elements to her brief bothered her. The first was the matter of a designed execution. Such acts were often planned when the perpetrator considered the victim to have committed an unpunished crime – and if not a crime, then an error for which forgiveness could not be bestowed. Or perhaps the man with the bullet in his skull had seen something he was not meant to see. And in those cases, the person who carried out the assassination might not be the person harbouring a grudge.

The second element that gave Maisie pause was that she believed Thomas might not have been as forthcoming as she could have been. In fact, she might have lied when she had told Maisie there was nothing more to tell. I want to know who killed him, that is the nub of the matter. The words seemed to echo in Maisie’s mind. Indeed, she had a distinct feeling that there was much more to the nub of the matter – after all, during the telephone call which Maisie had taken at Priscilla’s house, Thomas had suggested that murder might happen again. And again.

‘Well, the balloon has well and truly gone up now, hasn’t it?’ Billy Beale lifted the strap attached to a box containing his gas mask over his head and placed it on the table. ‘Morning, miss. Sorry I’m a bit late—’ He looked at the clock on the mantelpiece. ‘More than a bit, this morning. The trains were all over the place. Army on the move, that’s what it is – seen it all before, more’s the pity.’

Maisie had been standing by the floor-to-ceiling window, holding a cup of hot tea in her hand, when her assistant entered. She walked across to his desk. ‘Not to worry – I’ve not been here long myself, only enough time to make a cup of tea. Sandra’s late too.’

At that moment the door opened and Sandra Pickering came into the office, placing her handbag, a narrow document case, and her gas mask on her desk.

‘I’m so sorry – you would never believe—’

‘We’ve been in ages, Sandra – what kept you?’ asked Billy, a glint in his eye.

‘Take no notice of him,’ said Maisie. ‘We’ve all had the same trouble this morning. There’s the army mobilisation, and there are still a good number of children being evacuated.’

Sandra shook her head. ‘I’ve had enough of this already – I forget my gas mask half the time, and when you walk down the road there’s those big barrage balloons overhead, and you feel as if it’s the end of the world. Oh, and since the announcement yesterday, they’re adding to the sandbags around the Tube stations too. And they’ve been sandbagged for months now, all ready for this.’

‘Those balloons certainly block out the sun,’ said Maisie. She looked at Sandra and Billy in turn. ‘Get yourselves some tea’ – she nodded towards a tray set upon a low table close to the windows overlooking Fitzroy Square – ‘and then join me in my office. I want to go over work in hand, and we’ve a new case. An important one too.’

‘A murder, by any chance?’ asked Billy.

Maisie nodded as she stepped across the threshold into her office. ‘Oh, yes, Billy – it’s a murder.’

‘Good – something to take my mind off all this war business.’

When Maisie Dobbs, psychologist and investigator, moved into the first-floor office in Fitzroy Square almost ten years earlier, it had comprised one large room, entered via a door situated to the right at the top of the broad staircase that swept up from the main entrance. The Georgian mansion had originally been home to a family of some wealth, but the conversion of the property to offices on the ground and first floors, with flats above, had taken place some decades earlier, as industry boomed during the reign of Queen Victoria. Billy’s desk had been situated to the right upon entering the office, with Maisie’s alongside the ornate fireplace – though a temperamental gas fire had long since replaced coals. When Sandra began her employment with Maisie to assist with administration of the business, another desk had been squeezed in close to the door.

A series of events and a crisis of confidence had led Maisie to relinquish her business in 1933. Billy and Sandra had found alternative employment, and Maisie travelled overseas. When she returned to England in late 1937, it was as a widow, a woman who had lost the child she was carrying on the very day her husband was killed in a flying accident in Canada. That he was testing a new fighter aircraft was known by only a few – as far as the press was concerned, Viscount James Compton was an aviator, a wealthy but boyish man indulging his love of flight, looking down at the earth.

Drawn back to her work as an investigator, Maisie discovered the former office in Fitzroy Square was once more available for lease – but it was not quite the same office. In the intervening years a considerable amount of renovation had been carried out on the instructions of the interim tenant. There were now two rooms – a concertina door dividing the front room from an adjacent room had been installed, so when a visitor entered, Billy’s desk was still to the right of the door, and Sandra’s situated where Maisie’s desk had once been positioned. But to the left, a second spacious room – the office of a solicitor during her first tenancy – was now Maisie’s domain, with the doors drawn back unless privacy was required. Today the doors were wide open. Maisie’s desk was placed to the left of the room, with a long trestle-type table alongside the back window, overlooking a yard where someone – a ground-floor tenant, perhaps – had cleared away a mound of rubbish and was endeavouring to grow all manner of plants in a variety of terracotta pots.

As they stepped into Maisie’s office, Billy took a roll of plain wallpaper from a basket in the corner – a house painter friend of Billy’s passed on end-of-roll remnants – and pinned a length of about four feet onto the table. Maisie pulled a jar of coloured crayons towards her and placed a folder on the table in front of her chair, opening it to a page of notes.

‘“Frederick Addens, age thirty-eight, a refugee from Belgium during the war.”’ She sighed. ‘The last war, I suppose I should say.’ She paused. ‘He was found dead in a position indicating some sort of ritual assassination – though according to information given to our client by the police, they suspect the murder is a random killing motivated by theft.’ She pushed a sheet of paper towards Billy, who leant in so that Sandra could read at the same time. ‘As you can see, he was a railway engineer, working at St Pancras Station.’

‘One of them blokes you see diving onto the lines when the train comes in,’ said Billy, his finger on a line of typing. ‘Blimey, I’ve always thought that was a rotten job, down there where the rats run, all that oil, and that loco must be blimmin’ hot when it’s just reached the buffers. I tell you, I always wondered what would happen if the train started rolling and they hadn’t given the engineer time to get back onto the platform.’ He shook his head.

‘I think the guard checks, Billy,’ said Sandra.

‘What about our friends at Scotland Yard, miss?’ asked Billy. ‘What have they been doing about the case?’

‘They’ve pretty full hands at the moment – and though our client does not say as much, I suspect she believes there is an attitude of “victim not born here, so investigation can wait” on the part of the police. That might not have been my conclusion, but the fact remains that any investigation is not moving at a pace considered satisfactory by the client, so she has turned to me.’

‘She?’ asked Sandra.

Maisie slid another sheet of paper towards Billy and Sandra. ‘I’ve worked with Dr Francesca Thomas in the past – she is a formidable woman, and trustworthy in every regard.’

‘Where do we start?’

‘The first element of the investigation to underline is that we must move with utmost respect for the safety of Dr Thomas. It is not something she has had to request of me – she assumes our confidence, which of course we accord all our clients. But I would like us to be even more vigilant than usual. Dr Thomas was a member of La Dame Blanche during the war, and—’

‘La what?’ Billy interrupted.

‘La Dame Blanche was a Belgian resistance movement supported by the British government, comprised almost entirely of women – from schoolgirls to grandmothers. But with regard to Dr Thomas, I should add that she is more than capable of taking care of herself. We can assume she’s not currently sitting on her hands waiting for something to happen.’

‘Best not to get on the wrong side of her, then,’ said Billy.

‘Not if you value your throat, I would say.’ Maisie reached into the jar of crayons. ‘Anyway, as I said, I just wanted to mention that we need to be even more careful than ever. Right, let’s get started on the case map, shall we? I’m expecting a packet of additional documents from Dr Thomas this morning – it should arrive at any moment, I would imagine. That will help.’

Maisie wrote the name of the deceased on the paper, using a thick red crayon, and drew a circle around the words ‘Frederick Addens’. There was something childlike in the process, as if they were in primary school, beginning an innocent drawing. She smiled.

‘What is it?’ asked Billy.

Maisie looked up. ‘I was just thinking of Maurice,’ she said. ‘He always comes to mind when I start work on a new case. Not just because he was my teacher, but almost everything he said contained a lesson.’

‘He taught you about case maps, didn’t he?’ said Sandra.

‘Yes, when I first became his assistant. And it’s such a simple thing, really. Putting down every thought, every consideration, on a large sheet of paper to better see threads of connection. But he always used thick wax crayons in many colours – he said colour stirs the mind, that work on even the most difficult of cases becomes akin to playing. And because a case map is an act of creation, we bring the full breadth of our curiosity to the task.’

‘Instead of being old and stuck in our ways.’

‘Something like that, Billy.’

‘We’ll have to get used to seeing nothing but stuffy old grown-ups, won’t we?’ Sandra reached for a green crayon. ‘I walked down the street this morning to catch the bus, and it was so quiet – no children playing as I passed the school, no girls out with the long skipping rope, no boys kicking a ball about. It was as if the Pied Piper had been through and taken the lot of them – and the army were moving into the school! But no children in the streets.’ She looked at Billy. ‘What’s happening with yours, Billy?’

Billy shrugged. ‘It’s not so much Margaret I’m worried about, but the boys. Our little Billy’s not so little any more – eighteen soon, he is. And Bobby, he’s sixteen, doing well in his apprenticeship at the garage, and full of himself – I sometimes wish we’d never named him after my brother; he’s all hot-headed and knows everything. And look where that got his uncle.’ He turned to face Sandra. ‘My brother lied about his age to enlist after a girl shoved a white feather in his hand, and he ended up under a few feet of soil in a French field. That’s where it got him – and to think he could have just walked away and ignored the stupid girl.’

The bell above the door to the office began to ring, cutting into the mood of melancholy seeping into the conversation.

‘Not a moment too soon. Sandra, that will be the messenger we’re waiting for. Would you—’

‘Right away, miss.’

Sandra stepped out of the office. As her footsteps echoed away to the front door, Maisie reached out to lay her hand on Billy’s arm. ‘You’re the father to two young men now, Billy. Love them as you’ve always loved them, be the good father you’ve always been.’

‘It’s Doreen I worry about more than anything – she’s all right now, been on an even keel for a few years. But if something happens to one of those boys … I dread to think of it, really I do, miss. I don’t want her to lose her mind again – terrible thought, that is.’

Maisie nodded, looking up as Sandra returned to the room, and handed her an envelope. ‘Here you are, miss. It was all I could do to get him to give this envelope to me – I thought he would just barge up here, but I assured him I worked for you and I wasn’t a spy! I had to sign an official docket for him, to say I’d received the papers. He was very polite though, and nicely turned out – mind you, working for an embassy, you’d expect him to be. And his English was perfect.’

‘I’m sure Dr Thomas has very high standards for her staff.’ Maisie picked up a letter opener, unsealed the envelope, and began to lift out a sheaf of papers. ‘Sandra, would you have a go at getting the names of some of the associations set up to look after Belgian refugees during the war? Just in London, Kent, and Sussex for now. We’re going to need names, and more background information. And Billy – you’ve been an engineer, so I think you should talk to the staff at St Pancras in the first instance. Find out about Addens, his work, how he mixed with his fellow workers, that sort of thing. Try to find out if he seemed a little more flush with money than usual. And did he seem in any way different in the weeks before he died? Usual procedure at this point. I’ll go over to speak to his wife, perhaps the local pub landlord, and anyone else – without seeming too curious, I hope. I want us to understand the geography of the man’s life, and then we can start digging deeper. Oh, and I’ll be paying a visit to Detective Chief Inspector Caldwell, if I can see him today.’

‘Detective Chief Inspector? That little gnat’s a chief inspector?’ Billy’s eyes had widened.

‘Now then, Billy. Let’s be respectful, shall we?’ Maisie paused. ‘Though I know what you mean – it came as a bit of a shock to me, the “chief” bit. And before we all leave, let’s just go over those cases in hand – we’ll need to keep all the hoops spinning.’

They discussed the case of missing jewellery – not the sort of assignment Maisie would usually take on, but the client had been referred by Lady Rowan. Billy reported on a case regarding a wife who doubted the fidelity of her husband, and the trio conferred on another case concerning the whereabouts of a wealthy widow who appeared to have vanished, but who Maisie – having located the woman – knew very well just wanted to get away from her manipulative adult sons.

As Billy left and Sandra began a series of telephone calls, Maisie stood by the windows in the main office and watched her assistant make his way across the square. She could see from the way he carried himself that he was glad to be starting out on a bigger case. The dodgy wills and missing valuables were only engaging to a point; Billy always liked to sink his teeth into a more substantial assignment, one they were all working on together. But she knew he was troubled too, with one boy of enlistment age, another approaching it, and a wife with a history of mental illness. She would have to keep an eye on him. And on Sandra too. For if she was not mistaken, her newly married office administrator was expecting a child – and given her comments this morning, Sandra was fearful of what the future might hold for her firstborn.

For her part, Maisie knew that each day had to be taken as it came, and to do her work she must be flexible, to move the fabric of time as one might if sewing a difficult seam, perhaps stretching the linen to accommodate a stitch. She had learnt, long ago and in the intervening years when she was apart from all she loved, that to endure the most troubling times she had to break down time itself – one carefully crafted stitch after the other. If consideration of what the next hour might hold had been too difficult, then she thought only of another half an hour. She had explained this to Priscilla, once, and her friend had asked, ‘What’s the longest time you could bear, Maisie?’ And she had whispered, ‘Two minutes.’ But at some point the two minutes became five, and the five became ten, and as time marched on she was able to imagine a day ahead and then a week, until one day, almost without realising it, she could plan her life, could look forward to time laying out the tablecloth as if to say ‘Come, take what you will, be nourished and know that you can bear what might be on your horizon, the good and the ill.’

Now, on this day, some twenty-four hours after a new war had been declared, she wondered if she might have to begin reining in the future once again, with her thoughts only on the next hour, and the hour after that. She stepped back to the table and leafed through the folder of papers. As she read through the notes, the nagging feeling returned that Dr Francesca Thomas had not been entirely open with her regarding some aspect of the assignment. Or was it that, despite her regard for Thomas – the nature of her past, her bravery, and her ease with secrecy, subterfuge and danger – Maisie had never quite trusted her, despite her own assurances to Sandra and Billy?

Picking up her hat and document case, Maisie left the office – only to return to collect the gas mask she had left behind.

CHAPTER TWO

Twenty-five Larkin Street, in Fulham, was just beyond the World’s End area of Chelsea. Maisie travelled by underground railway to Walham Green Station, and walked to Larkin Street. Having been born in Lambeth and engaged in work that took her from the poorest streets to the most exclusive crescents in London, Maisie had no fear of a slum. Though now a woman of some wealth, for the most part she dressed in an unassuming manner. Her clothes were good but plain, and it was not her way to flaunt her status in any perceptible fashion. Thus she walked with ease through an area so called because King James II – who rode regularly along the King’s Road in his day – had described the region as being at the end of the world.

For Frederick Addens it had been a world that had saved his life, following his escape from the German army occupying Belgium. According to the notes furnished by Thomas, Addens had entered Britain aboard a fishing boat that came aground just outside Dymchurch. Some twenty people had made the crossing in storms plaguing the English Channel – it was not a long journey by any means, but for refugees fleeing an enemy, it might as well have been a million miles. Addens was almost sixteen when he at last reached safety, the same age as the century. He was married two years later, to an English girl, Enid Parsons, a young woman three years older than her new husband. Her first sweetheart, the boy she had loved since childhood and thought herself destined to marry, had perished in August 1916, in one of the many battles fought along the Somme Valley in France from July to November that year.

Maisie slowed her pace. How had it been for the young couple, both grieving for what had been lost, yet embarking on a new life together? She understood loss, understood how it could leach into every fibre of one’s being; how it could dull the shine on a sunny day, and how it could replace happiness with doubt, giving rise to a lingering fear that good fortune might be snatched back at any time. Yet they had raised a son and a daughter, and now Enid Addens – a woman just a little older than herself – was enduring the brutal death of her husband, and perhaps the departure of her son to another battlefield. Maisie wondered how she would ever be able to speak to the woman, to question her about her husband’s murder. The truth of the matter, that she might stir the woman’s heart with her enquiries, almost made her turn back to the office. And then she remembered the trust placed in her by Francesca Thomas, and she knew she had it within her to gain the widow’s confidence. Detective Chief Inspector Caldwell’s less compassionate approach, on the other hand, might have cost him valuable time and information.

Arriving at the rented terrace house, Maisie appraised the property where Frederick Addens had lived with his family. It was clear they had endeavoured to keep a clean home in a grubby area. Unlike those on either side, number 25 had received a fresh coat of paint in recent years, probably work carried out by Addens and his son. What was his name? Ah, yes, Arthur, named for Enid’s brother, who had died on the very same day, in the same battle, as her sweetheart. The girl was named Dorothy, and called ‘Dottie’ by the family. She bore her grandmother’s name. Maisie wondered why there was no hint of Addens’ relatives in the naming of their children.

The path had been swept and the tiled doorstep looked as if it received a generous lick of Cardinal red tile polish every week. Someone had tried to grow flowers in the postage stamp of a front garden, but the blooms were patchy. Maisie approached the front door and lifted the knocker, rapping three times. The drawn curtains at the side of the bay window were tweaked back, indicating someone was at home. She rapped twice more. Footsteps approached, and after a lock was turned and a chain withdrawn, the door opened, but only enough to allow a young woman with fair hair and bloodshot eyes an opportunity to size up the caller.

Maisie smiled, her manner exuding kindness. ‘Hello, you must be Miss Addens. My name is Maisie Dobbs. One of your late father’s compatriots has asked me to visit you and your mother.’

‘I don’t understand,’ said Dorothy Addens.

‘I’m calling on behalf of someone who knew your father in Belgium. I am an investigator, and I believe Scotland Yard might have missed a few details regarding the circumstances of your father’s death.’

The young woman waited a few seconds, as if considering the request put to her by the unexpected caller. ‘Just a minute,’ she said. ‘And I have to shut the door on you. Sorry.’

‘That’s all ri—’ Before Maisie could finish the sentence, the door closed. She heard footsteps receding on the other side, and Dorothy Addens calling, ‘Mum. Mum, there’s a woman to see you, from Belgium.’

Two minutes later, Addens returned, opening the door as Maisie was looking up at the barrage balloons overhead. ‘They’re an eyesore, aren’t they?’

‘Horrible. But I suppose they make us all a bit safer,’ said Maisie.

‘They didn’t keep my dad safe, did they?’ Addens’ tone was sharp, then softened. ‘Sorry, Miss Dobbs – it was Miss Dobbs, wasn’t it? We’re all very upset around here. My mother’s had a terrible time of it, what with my brother joining the army to top off everything else. Come in. She said she’ll see you. But please don’t stay long – she’s very tired.’

‘Of course.’

Maisie followed Dorothy Addens along a passageway into the kitchen at the back of the house. From the doors to the right, leading to a parlour and dining room, to the kitchen overlooking a narrow garden planted with vegetables, the house was like so many she had visited, and like thousands in towns across the country. They had been built to meet the demand for housing during the exodus of workers from the country in the middle of the last century: people beckoned by a promise of opportunity as the boom in industry powered by steam, steel, and petrol seemed poised to render agriculture yesterday’s business. Each house in Larkin Street comprised three floors, and Maisie suspected the top-floor rooms might be rented to lodgers.

‘Mum, this is Miss Dobbs.’ Dorothy Addens pulled out a seat for Maisie and took the chair next to her mother, who sat with her elbows on the oilcloth cover spread across the table, twisting a handkerchief over and over in her hands.

With a grey, lined face and hair scraped back into a bun at the base of her neck, Enid Addens could well have passed for a grandmother. Maisie remembered seeing her own reflection in a mirror after James was killed, and she wondered now if she had appeared so worn, so beaten by circumstance.

Frederick Addens’ widow looked up at Maisie. ‘You know my husband?’

Maisie noticed how Enid had used the present tense. The knowledge that her husband was dead had not yet seeped into the deepest part of her heart. Speaking of him as no longer being in her world likely felt akin to a knife thrust into her chest. Maisie coughed, laying a hand against the fabric of her jacket, close to her own heart – the cough had deflected attention from the pain she felt when she observed the woman’s distress. She did not want to slip.

‘I know someone who has asked me to look into the circumstances of your husband’s passing, Mrs Addens.’ Maisie opened her bag, took out a calling card, and placed it in front of the woman. ‘I am by training an investigator. I assist my clients in situations where questions remain regarding something untoward that has happened. My client is from Belgium, and wants to ensure the person responsible for your husband’s death is found, and so came to me.’

‘Someone killed my father, Miss Dobbs – if the police can’t find out who did it, then how can you? Eh? I don’t want you coming here to upset my mother, even if you have the best of intentions.’

Enid Addens laid a hand on her daughter’s shoulder. ‘Now then, Dottie. You’re the one getting upset. I’d like to hear what the lady has to say. Be a good girl and put the kettle on – make us all a nice cup of tea.’

Dorothy Addens scraped back her chair and stepped across to the stove.

‘And open that back door, love,’ added her mother. ‘What with this weather and that stove, it’s like a bakehouse in here.’

‘It is close, isn’t it, Mrs Addens? Would you mind if I took off my hat and jacket?’ asked Maisie.

‘Not at all, please – we don’t stand on ceremony in this house.’ Enid looked up at Maisie, her eyes filling with tears. ‘I don’t know what will become of us, without Fred.’

Maisie took a breath. Yes, she would entrust the woman with something of herself. She would touch her hand, tell her a little about her past, encourage the sharing of a confidence.

‘I know what it is to lose your husband, Mrs Addens. My husband was killed a few years ago. It takes time to recover yourself – and I still grieve for him.’

Enid’s stare seemed to dare Maisie to look away, as if she were measuring the depth of Maisie’s sadness to see if it matched her own. In time she spoke again. ‘So, you’re an investigator and you want to find out who killed my husband. I will answer your questions as best I can. Dottie, bring the tea and you sit down too – your memory’s better than mine.’ She looked up at her daughter as Dottie placed cups of tea in front of her mother and Maisie. Enid turned to Maisie. ‘She’ll be back to work tomorrow – she’s already taken too much time off on account of me. We need the money, though the railway had a whip-round for us, so we won’t be short for a while, and my son will be sending money home.’

Maisie reached into her bag and brought out a notebook. ‘Mrs Addens, can you tell me about your husband’s last morning? It was at the end of the first week of August, wasn’t it?’

‘Yes, it was a Friday the fourth of August. I remember it, everything about that day now. It’s as if the news made everything sort of big – do you know what I mean?’ She looked at Maisie, as if to see if she shared the experience.

Maisie nodded. ‘I know very well what you mean, Mrs Addens – I could describe even the smallest detail about the day my husband died. It’s branded into my memory.’

‘I’d been working in the shop – I’ve a job at a haberdashery shop up on Fulham High Street, part-time. I hadn’t long been home, and was sitting down having five minutes to myself with a cup of tea to listen to the news on the wireless, and the police came to the door. I remember, I was thinking about that General Franco – they were saying how he had just declared that he would only answer to God and to history, and he’d set himself up as the ruler of Spain. And after all they’ve gone through, I thought to myself, now they’ve got a dictator in charge. Makes you wonder what’s going to happen to us.’ She looked away, fixing her gaze on the garden.

‘My father was interested in what goes on in the rest of the world, Miss Dobbs.’ Dorothy Addens lifted a cup to her lips. ‘So we all have opinions in this house.’

Maisie smiled, understanding that the younger woman felt the need to underline her credentials. She wanted Maisie to know that, despite the area in which she was born, she, Dorothy Addens, was an intelligent woman, the daughter of a man who understood the importance of educating oneself.

Maisie turned back to Enid. ‘What happened then – what did the police say?’

‘There was a man from the railway police with them, and someone from the railways board. It was a right little crowd on my doorstep. I thought straightaway that my husband had been killed by a train – one of Frederick’s mates was killed by a loco a few years ago, and another scalded to death by steam. I wondered what had happened. And I couldn’t move. I was stuck to the threshold, but the railway policeman took me by the arm and led me into the parlour, and he sat me down and said that Frederick had been murdered. All these men were sitting in my parlour looking even bigger, uncomfortable perching on the edges of the chairs, while this Detective Chief Inspector told me what had happened. Frederick had been killed outside the station, down an alley not far away. They don’t know what he was doing there, because he didn’t knock off work until six on a Friday, as a rule – unless he had overtime – and it happened at four, or so they think. They told me he had been shot.’

‘And who identified the body?’

‘One of his mates, a fellow he worked with. Mike Elliot. I couldn’t go to see my husband, on account of what they said were the circumstances, but Dottie – she came home while they were here – she said they were covering it up. And she said it to their faces, told them that the reason we couldn’t see her dad was that it was so bad and they didn’t want to tell us the truth. She can be a terror, can Dottie – if she’s put out, she can get very uppity, and she was uppity with the police. Takes it all in here, you see.’ Enid Addens tapped her chest with her hand as she looked at her daughter.

‘Mum! I’m all right. Just tell Miss Dobbs what she needs to know – you don’t need to ramble about me.’

Enid gave a half smile. ‘She wouldn’t have cried in front of them, so her temper started up. That’s how it is with some people. Friend of mine had a dog who was a right growler, showed his teeth to anyone who came up to him, but it was as if his wires had been crossed when he was a pup – that growl was a purr, and all he wanted was a pet. Well, she growled at the police until I sent her off to make a pot of tea. I tell you, Miss Dobbs, I could hear that girl crying her eyes out in the kitchen, and I knew that all she wanted was someone to comfort her – and I couldn’t do it because it was as if I was paralysed in my chair. The railway policeman – he was a big fellow, looked like a family man – he went out and I heard him say, “That’s it, love, get it out of your system, you have a good cry.”’

‘He came where he wasn’t wanted. If you remember, Mum, I sent him off packing back to the parlour.’ Dottie reached into the pocket of her summer dress and pulled out a packet of cigarettes.

‘Go outside if you want to do that, Dottie. I have enough trouble with the flue on that stove, without you smoking up the kitchen.’

Dottie Addens pushed back her chair and flounced out to the back garden, where Maisie could see her light her cigarette and inhale deeply. She held her head back and blew out a series of smoke rings.

‘I’m sorry about that. She’s normally such a good girl – has some spirit, but she idolised her father. He always said she reminded him of himself, when he was younger – well, it must have been much younger, because he was married to me at eighteen.’ Enid Addens rubbed her upper arms, tears welling in her eyes again. ‘He was so young, really, but a man already. He knew what he wanted, and he wanted a wife and a family, and to be settled – that’s what he wanted, and he chose me, so I was a very lucky woman. I thought I’d lost my chance, and then Frederick came along.’

Maisie brought her attention back to Enid. ‘Mrs Addens. I’m used to meeting people in these difficult situations – I would be just like Dorothy if I’d lost my father.’ She paused for a second. ‘Can you tell me what else the detective said?’