9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

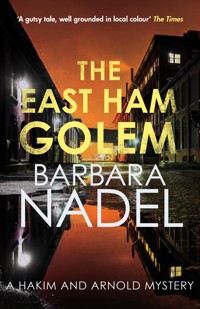

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Hakim & Arnold

- Sprache: Englisch

Ever since it was built in 1912, Woolwich Foot Tunnel has been the subject of rumour and speculation. Running underneath the Thames it connects north and south, and in the hot summer of 1976, when young John Saunders apparently entered the Tunnel and completely disappeared on his way to his sister's house, it was a grim and frightening place. John was never seen again until he re-emerged forty-two years later, complete with an American accent. Happy to submit to the DNA testing his sister Brenda demands, this man is definitely John Saunders, but when nothing that he tells Brenda rings true, she decides to enlist the services of Hakim and Arnold to try and uncover the truth. He is who he says he is, but his story about what happened between 1976 and 2018 makes no sense. Why has he come back now . what does he want?

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 413

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

A TIME TO DIE

BARBARA NADEL

5

To every kid who ever walked through the Woolwich Foot Tunnel

6

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

Where was the little shit-bag? Brenda lit one cigarette off the butt of her last smoke and breathed out shakily. John was ten and so he should be able to get himself from Silvertown, through the foot tunnel to Woolwich with no bother. But this was John …

Why was her baby brother such a div? Was it because he’d been born so long after she had, that their parents had babied him? Hardly. Brenda couldn’t remember a time when her dad wasn’t mostly down the pub and her mum just sort of wafted around the flat in a tranquillised fug. Since the old man had left, to no doubt drink himself to death, John had largely been abandoned to his own devices. And maybe that was the problem. Always a dreamer, John wandered around aimlessly when he wasn’t at school. With no friends to take him out of himself, the kid was like a tit in a trance.8

Brenda had only offered to have the boy for the day because her mum had a hospital appointment. Devon, Brenda’s husband, had no great love for the kid and so she hadn’t wanted to take him, not really. She’d seen him wave at her from the northern shore of the Thames before he went into the Edwardian rotunda that marked the entrance to the tunnel under the river, so she knew he was on his way. Brenda looked at her watch. The silly sod was probably daydreaming down there, counting the tiles on the walls or something else equally as daft.

Nobody really liked walking through the old foot tunnel. It was smelly and kids mucked about down there. But it was the only way to get from North Woolwich to South Woolwich without taking the ferry. That had been out of action for a week and so it was the tunnel or nothing.

People got mugged down in the damp hideous old passage under the river, which was why Brenda had made sure John waved to her before he crossed, so that she could time him. It took about ten minutes to walk briskly through the tunnel, which was what Brenda, if she had to use it at all, made sure she always did. The place gave her the heebie-jeebies with its jaundiced lighting, musty smell and occasional alarming drip from the tiled ceiling. Her brother, with his morbid interest in anything dark, creepy and generally putrid, was probably having a bloody brilliant time down there imagining ghosts, running away from weird noises and frightening the shit out of himself. He was a strange little tyke – which would have been fine – had he not been so unlikeable.

What it was about John nobody seemed able to take to was something Brenda could never fully understand – he wasn’t really a bad kid. Maybe it was the fact that he never appeared to listen to anything anyone ever said? The feeling he gave off9of being away with the fairies all the time? Or was it perhaps the suspicion Brenda had that this airy-fairy thing was all an act and that underneath all of it was a calculating mind that knew exactly what it was doing.

As far as Brenda was aware, John had never bullied anyone or been cruel to animals. He didn’t interact with anyone – animal or human. But he did have a lot of cuts and scars on his arms and legs and she wondered whether he was hurting himself. Maybe for attention? Not that it had succeeded. When Brenda had told her mother about John’s wounds all she had said had been, ‘What you talking about? I don’t know of no wounds.’

Brenda looked at her watch. The silly sod had been down there for nearly twenty bloody minutes! What the fuck was he up to down there?10

ONE

‘Took me over forty years to find the answer to that question,’ Brenda Joseph said. ‘If I have …’

‘Which is why you’re here?’

‘Yeah.’

Brenda Joseph was a small, dark woman in her early sixties. Twice married and mother to seven children, she was also the possessor of a strange experience, deep in her past, involving her younger brother, John. During the long, hot summer of 1976, ten-year-old John Saunders had gone down into the Edwardian foot tunnel at North Woolwich and disappeared. In spite of the best efforts of his sister, who, after half an hour waiting on the southern shore, had entered the tunnel herself to look for him, plus an extensive police investigation, nothing had been heard from or of John until he had, apparently, arrived at Brenda’s house in Canning Town just before Christmas 2018. 12

‘I’ve never found out how he got my address,’ Brenda told private detective Mumtaz Hakim. ‘I moved there back in 2008 when I married Des.’

The Arnold Private Detective Agency had been operating out of its tiny office on Green Street Upton Park since 2010. Opened initially as a one-man band by ex-policeman Lee Arnold, Mumtaz had joined the firm in 2012. A psychology graduate and mother of one, Mumtaz was the only full-time employee apart from Arnold himself who was currently out on a job in Romford.

‘It’s difficult for me to say whether or not this John looks like our John,’ Brenda continued. ‘He was ten when I last saw him.’

‘What about other members of your family?’

‘Mum died back in 1990 and me dad left us before John disappeared,’ Brenda said. ‘He’s dead now. All the aunts and uncles have gone too, and none of me cousins really kept in touch. Anyway, John weren’t exactly someone you’d remember. Away with the fairies most of the time. He was a strange kid.’

‘Friends?’

‘He didn’t have any. Spent most of his time drifting about on his own. Done a lot of reading in his bedroom.’ She leant forwards. ‘We’ve had DNA tests, me and this bloke. According to them he is my brother, but … There’s something wrong here.’

‘In what sense?’

‘I dunno. That’s what’s so horrible about all this. I should be grateful that he’s come back after all these years, but I’m not. And the story he tells about what happened is just, well, it’s fantastic – and not in a good way.’

‘So tell me,’ Mumtaz said.

13‘He says our dad was waiting for him in the tunnel,’ Brenda said. ‘I never saw him. I saw John wave from the other end just before he went in, but I never saw the old man and I certainly never saw John come out my end. Anyway, the way this bloke tells it, they come up the stairs and not in the lift, and then they waited until I was looking away until they come out. What do I know? But anyway, the first thing that occurred to me when this “John” was telling his tale was why?’

‘Why?’

‘Why did our old man, Reg, take him? He was a drinker, he didn’t ever seem to me as if he liked kids and he never wanted to work. And yet John claims that Reg took him to America.’

‘People can change.’

‘Normally I’d say, right enough, of course they can, if I hadn’t been to my old man’s funeral with me mum back in 1982.’

Mumtaz leant back in her chair. She hadn’t been expecting that.

‘We had to go out to Wales,’ Brenda continued. ‘Mum identified the body and everything.’

‘Do you know what he was doing in Wales?’

Brenda shrugged. ‘He died of cirrhosis of the liver and so he hadn’t changed his ways. Me and Mum met this nun who looked after him when he was dying. I s’pose I should’ve paid more attention to what she said, but I never. I was so mad at the old git, I just wanted to get the funeral over with and get back home to the kids. Now Mum’s dead I don’t stand a chance of knowing what the woman was on about. Although, that said, what I do know is that Dad was a tramp by that time. That was why Mum had to go and identify him. Although the nuns took him in, there was no proof on him of who he was.’

‘So your father must have told the nuns his name.’ 14

‘I s’pose so.’

‘And what did this John say when you told him about your father’s death?’

‘He thanked me. Said he hadn’t known.’

‘So, your father takes him to America and then …’

Brenda breathed in deeply. ‘Well, this is where it all gets a bit mental,’ she said.

Standing up beside a tea stall in the middle of Romford Market seemed to be a strange place to have a conversation about a dead marriage, but then the man Lee Arnold had come to see, Jason Pritchard, was far from being what people thought of as your typical ‘Essex’ man.

The wrong side of fifty and with a nose that was splattered rather than placed at the middle of his face, Jason looked and talked the part but, as his oldest mate, Dave, had told Lee right from the start, ‘He’s got some funny ideas.’

The top of Jason’s ‘funny ideas’ list concerned Britain’s referendum back in 2016 about whether or not to stay in or come out of the European Union. The country had voted by a narrow margin to come out, with Romford being one of the most determinedly ‘Brexit’ areas of the country.

‘But not him,’ Dave had said pointing to Jason when Lee had first met the blokes. ‘Talks about it being a financial disaster. I don’t know where he gets it from.’

Lee did. He too had voted to remain in the EU and could fully understand Jason’s point of view.

‘You hear ’em round here all the time,’ Jason told Lee as Dave walked away. ‘“Just get us out!” they say. Tossers. Anyway, sick to buggery of Brexit, what’s happening with that old slapper?’

The ‘old slapper’ in question was Jason’s ex-wife, Lorraine. The 15two of them had parted a year before and Jason had started divorce proceedings. But Lorraine was apparently playing rough and was claiming that her ex had left her destitute when he’d taken off with a bingo caller from Southend. She wanted more money. Jason, for his part, contended that he’d given Lorraine their house, debt-free, that he still gave her an allowance and that the only reason she was destitute was because she was addicted to Tinder, the online dating site. Officially no loans had been taken out against the considerable equity in the house, but that didn’t mean they didn’t exist.

‘She had a handbag spree at Lakeside at the weekend,’ Lee said.

The only thing that had made Lee’s trip to Lakeside Shopping Centre at all pleasant had been the fact that it had been under cover. The previous Saturday had been very wet.

‘How much?’ Jason asked.

‘Best part of two and a half grand.’

‘Fuck me!’

‘She’s no fool,’ Lee said. ‘On one level.’

Lorraine Pritchard had started funding her addiction to, mainly, younger men, by taking out small loans in pawnshops against her jewellery. By Jason’s own admission, Lorraine’s ‘jewels’ were mainly Ratners specials, so she hadn’t made much. This had then progressed to taking out unsecured loans with various high street loan companies, which had now, her husband suspected, progressed further to coming under the influence of actual loan sharks. As yet, Jason didn’t know who they were. But if she carried on her life of luxury, it wouldn’t be long before Lorraine got hurt. And, although he wanted nothing more to do with his ex, Jason didn’t want her to either lose their house or get hurt.

‘You know where it’s coming from yet?’ Jason asked.

Lee shook his head. ‘Not exactly.’ 16

‘What’s that mean?’

‘Means that I’ve got some ideas but nothing concrete,’ Lee said.

Lorraine was making occasional trips out to Langdon Hills in Thurrock, which didn’t make a lot of sense given that all her family and friends lived in Romford. Also, she had no car and so every trip that she made out to this ‘posh’ part of Thurrock based around a golf club, was difficult and costly. Lee didn’t know any obvious ‘villains’ who lived in that area, but that didn’t mean they didn’t exist. The house she visited was registered to a Mr and Mrs Barzan Rajput. The name rang no bells, but why was she going there? And how had she got to know these people? He’d asked Jason about any possible Langdon Hills connections before, but he’d come up empty. Lee didn’t want to labour the point now.

‘She been out this week?’ Jason asked.

Unlike the ‘old days’, following people engaged in sexual relationships wasn’t so easy in the twenty-first century. Back when he’d been a copper, hooky types tended to meet their ‘dates’ in pubs, clubs and discos. But in the modern world of ‘hook-ups’ this all happened online, and although Lee had ‘friended’ Lorraine on social media, he had noticed that she was rather reticent when it came to details about her movements. But for the skilled PI, for whom patience wasn’t so much a virtue as a necessity, this was not a great problem.

‘Sunday she had lunch at a pub in Havering-atte-Bower and then went back with the bloke she’d met there for two hours.’

‘Some suit?’

‘He wore a suit but it didn’t define him,’ Lee said. ‘His home turned out to be of the mobile variety.’

‘Slummin’ it.’

‘Not really, no,’ Lee said. ‘He was probably twenty-five, tops. 17What he lacked in readies he more than made up for in youth.’

Jason shook his head. ‘Dirty mare.’

‘Dad used to work on the docks when I was a kid,’ Brenda said. ‘Then when everything moved down to Tilbury, he got a job on the cruise ships. But he got caught nicking stuff and so they sacked him. But, probably because he was always good for a pint or twelve, he knew everyone wherever he worked. Mainly he knew the villains. Someone must’ve got him and John on that ship across the Atlantic. This John man didn’t talk about that much.’

Mumtaz noticed how Brenda never referred to John as her brother, in spite of the apparent DNA proof.

‘All I know is they landed at New York where they were met by this couple.’ She shook her head. ‘It sounds mad, especially if you’d known me dad. How he found these people … Well anyway, they were called the Gustavssons. This John when he mentioned them started going on about them being billionaires and all that, and I thought he was full of shit, you know. My dad was a toerag, how’d he get to be with people like them? But I looked them up. Or rather I got our Kenton to look them up on Google and there they were. Etta and Michael Gustavsson of Orange County, California, one son – John. They’re bloody loaded.’

Mumtaz was just thinking that she’d never heard of them when Brenda said, ‘Funny people, though. All that money but you’ll never see their names in the papers or nothing. This John geezer’s their only heir too! And he’s got no family, so he says, so it’ll all come to my lot. So he says. But it don’t add up.’

Mumtaz frowned.

‘I mean, don’t think I’m being grasping or nothing, but if you 18was rich and then you come back to your family after donkey’s years, don’t you think you’d want them to see you’d done well? Like wearing nice clothes? Driving up in a posh car?’

‘He didn’t?’

‘Rocked up in a taxi from Plaistow, after getting the Tube, so he said. Looked like he’d slept in his clothes.’

‘If he’s come from America then maybe he had,’ Mumtaz said. ‘On the plane.’

‘Yeah, but why? If you had a lot of money you’d go first class, wouldn’t you? I know I would. Anyway, that’s just a detail really. What I’m really interested to know is why he’s here.’

‘Why does he say he’s here?’

‘To see us.’ She shook her head. ‘So he says.’

‘But you don’t believe him?’

‘I don’t.’

‘Why not?’

Brenda sighed. ‘Look, I can understand why he don’t want to stay with us. He could, I’ve offered, but he says he don’t want to be no bother. I’m not saying the house is a tip, but … I got kids still at home, Des, and then there’s his youngest boy, in and out as he pleases. Grandchildren … It’s like Charing Cross Station, but if he has really come to see us why is he staying up West? And why in a Travelodge?’

Mumtaz said, ‘Not all rich people want to splash their money around.’

‘Oh, I get that his people are not flash. They wouldn’t hide themselves away if they was. But he don’t spend time with us. He says he’s over here to see us but then he’s always off somewhere. When he is with us, he sits in a corner and reads. And yes, I know he might be embarrassed and maybe he wants to see things after so long away but … This is going to sound 19daft, but I think he’s here for some other reason. I feel we’re an excuse. I don’t trust him.’ She moved in closer to Mumtaz and said, ‘I mean, I don’t know him, do I?’

‘Tel.’

‘Jase.’

There was no actual hostility between the two men, but Lee could see there was no love lost either.

When the older, much fatter, man had walked past he said to Jason, ‘Who was that?’

Jason rolled his eyes. ‘Her uncle.’

‘What?’

‘The missus,’ he said. ‘Terry Gilbert. He’s the only member of her family who’ll so much as pass the time of day. Not that I blame ’em. Some’d say I done wrong going off with Sandra, especially the wife’s family. But living with Lorraine had been doing my head in for years. And it’s not like the kids are babies …’

‘So, could he be a possible source … ?’

‘For Lorraine? Nah. Reason he’s still civil to me is that his family can’t stand the sight of him.’

‘Why not?’

Jason offered Lee a fag, which he took and then they both lit up.

‘They call him Tall Tel round here,’ Jason said. ‘And, yeah, I know he’s knee-high to a short cat, but you know how it is.’

Lee nodded. Many people in Romford originated from the East End where there was a long tradition of inappropriate or strange nicknames. Lee’s mother’s sister, his Auntie Grace, for instance, was known to everyone as ‘Polly’ because she was always putting the kettle on. 20

‘Yeah.’

‘Mind you,’ Jason said. ‘There’s truth in the Tall Tel thing because he’s always telling tales.’

‘What? Lies?’

‘Depends how you view these things,’ Jason said. ‘He’s always been, so he says, convinced the earth is flat. I thought he just done it for attention when I first met him, but he don’t. Sods off every so often to look for the Loch Ness Monster, thinks there’s a coven of witches that operate out of St Paul’s Cathedral. You wanna hear him about the tunnels underneath the Thames! And, of course, now he’s full of shit about George Soros taking over the world. Donald Trump’s his kind of geezer, which tells you all you need to know about Terry Gilbert and part of the reason why I left his niece.’

‘Lorraine tell tall stories?’

‘Nah. Not really. She just never questioned nothing. Long as she got her manicures and her hair done, she never give a shit about nothing important. I got fucked off with it. I mean, I know I look like the type of bloke who drives a Range Rover and puts up UKIP posters in me front windows, but I’m not like that and neither’s Sandra.’

‘Which is why you fell for her.’

‘Yeah.’ He looked up at the cloud-filled sky and then he said, ‘That and her tits.’

Shortly after Brenda Joseph left the office, Mumtaz took a trip down to North Woolwich. It was many years since she’d walked through the old foot tunnel and now, in view of Brenda’s story, she felt as if she needed to reacquaint herself with it. She parked up just behind a derelict pub on Manor Way and began to walk down towards the northern embarkation point for the Woolwich 21Ferry. The entrance to the foot tunnel was just in front of the slip road for vehicles queuing for the boat.

With grey and cloudy skies up above and a low, riverine landscape all around, her walk was far from cheerful. North Woolwich was one of the forgotten corners of London. Heavily bombed in World War Two, it had been redeveloped first in the 1960s when numerous poorly built tower blocks sprang up. The Tube had never come out as far as North Woolwich and so, in those days, it was only served by infrequent trains on the old overground North London Line. But then in the eighties and nineties a second wave of development hit, bringing with it, eventually, the Docklands Light Railway and very pricey flats for rich people with uninterrupted river views. But, for all that, the tower blocks still stood, as did the cheap takeaway joints, the bookies and the corner shops where, if you knew the right people, you could access cheap fags.

As ever, the queue for the free ferry across the Thames was long and those waiting to use the foot tunnel were few. Built back in 1912, Woolwich Foot Tunnel was entered via matching brick-built, copper-roofed rotundas on the northern and southern shores of the river. On the northern shore the building was plonked on its own in the middle of a tangle of roads servicing the ferry and local buses. But on the southern shore the rotunda was less easy to discern. Before she descended, Mumtaz looked across the Thames to see how quickly she could spot it. It wasn’t easy. The southern rotunda was hemmed in by newer buildings. But it was possible, as Brenda Joseph had claimed, to see someone waving outside the opposite structure.

Mumtaz entered the northern rotunda. The smell that hit her, a mixture of piss and fag ash, was very familiar in this kind of environment. Although brick-built the inside of the rotunda was 22lined with what had once been white, now grey, tiles. Similar in size and appearance to the tiles one routinely found in Victorian toilets, these were what Lee always called ‘bog tiles’ and they always smelt like this. Many years ago, Mumtaz remembered walking down the staircase behind the lift to the tunnel and so she pressed the button to call the elevator. As she recalled, those stairs had been spiral and dark and she’d felt as if she was descending into hell. The lift was at least quick, even if it too was dark and unsettling with its strange wooden panels scarred by unimaginative graffiti. When the automatic doors opened, she found herself looking down a deserted tile-lined tube illuminated by flickering yellow lights. On the ground, down the middle of the tunnel was a long drainage hollow. Everything about this place seemed to be designed to cause the user anxiety.

TWO

‘What made you go down there on your own?’ Lee asked.

Mumtaz sipped from the cup of tea he’d just put down in front of her.

‘I wanted to see whether the tunnel was still as horrible as I remembered,’ she said.

‘And it was.’

‘Of course. It’s in Woolwich, the land time forgot,’ she said.

‘And I suppose you walked back through it?’

‘Yes.’

He rolled his eyes. It had been a long day. The traffic had been bad going to and returning from Romford and Mumtaz’s latest client’s problem had sounded odd.

Lee sat down behind his desk. ‘I’m always wary of jobs based on feelings,’ he said. ‘I mean if this woman and her brother have had DNA tests …’ 24

‘She’s not disputing that he’s her brother,’ Mumtaz said. ‘She’s just wary about his motives.’

‘So he’s a bit weird …’ Lee turned to his computer screen. ‘Says here that the Gustavssons are major donors to Christian charities. Also says they’re staunch Republicans. Maybe John Saunders has come over here to support Trump.’

American president Donald Trump was due to arrive in London for a state visit in five days’ time on the 3rd June.

‘Why?’

‘What – why come over here to support Trump?’ Lee laughed. ‘Well, no one else is.’

‘Yes, but why would John Saunders keep that from his sister?’

‘Embarrassment?’

‘Brenda Joseph doesn’t strike me as the kind of woman who’d be necessarily against Trump,’ Mumtaz said.

Lee shrugged. ‘So what did you say to her?’

‘I said I’d look into it,’ she said. ‘He’s staying at the Travelodge in Marylebone. He arrived just before Christmas and went straight from the airport to Brenda’s house in Canning Town. He says he found her through Facebook, although she’d no proof of that.’

‘So he’s been here six months and she’s only got round to feeling strange about him now?’

Mumtaz shrugged. ‘Seems so. Maybe she’s had enough of him.’

‘What about this DNA test?’

‘My understanding is that it’s one of those quick, off-the-peg jobs,’ Mumtaz said.

‘Which can be wrong.’

‘Mmm. Brenda and her husband Des both work in low-paid jobs for the NHS. He’s a porter and she’s a cleaner,’ Mumtaz said. ‘They rent their house from the council and between them 25they’ve got seven kids plus assorted grandchildren. John can’t want anything from her, she hasn’t got anything.’

‘What does he do?’

‘He’s part of his adoptive parents’ charity. I don’t think that he does work, as such. What does it say about him on Wiki?’

‘Just that he exists,’ Lee said. ‘Born 1966. That’s it. Maybe he doesn’t want anything from his sister? Maybe he just wants to know her and her family.’

‘It would seem so. But his behaviour isn’t what you’d call normal. He insists on seeing Brenda every day, at her house for preference. Then all he does is sit about and read.’

‘Maybe he’s autistic?’

‘Really?’ she shook her head. ‘Lee, that’s a bit of a jump …’

‘Obsessive behaviour …’

‘Autistic people don’t conform to one size fits all. I think you may have watched Rain Man one too many times. Or maybe you’re right? I have yet to see this man. And then there’s the story about how he came to be in America. I mean, is it possible for someone to travel across the Atlantic on a liner, get off in New York and just become someone else?’

Lee said, ‘Probably. I don’t know how, but sometimes people can just get through the system. When I was a copper, we had a case of a psychiatric patient who somehow flew to Dallas, Texas. So Goodmayes Hospital to Dallas with no passport and an empty birdcage as luggage. How he even got on the plane remains a mystery. Flight attendants claimed they just took the cage from him and then let him on. No passports checks. You ask me! God knows how he did it!’

‘Really?’

‘Really. But if this Gustavsson pair met John and his dad in New York, was that maybe prearranged? If you’re right about 26the dad not being much involved with the kids, then did he somehow do a deal with these people? For the kid?’

Brenda had started out cooking very English food for her brother when he came round, but now her husband was getting bored, not to mention the kids.

‘Not bloody meat pie again!’ her daughter Kimberly said when she saw her mother popping a steak and kidney into the oven.

John was only next door in the living room and so Brenda shushed her.

Kimberly lowered her voice. ‘All right, then,’ she said. ‘But count me out, yeah?’

‘What …’

‘I’m meeting up with Jaqueshia later − I’ll eat round hers.’

Kimberly was Brenda’s youngest child, the only one of the couple’s many kids who was the product of both of them. At sixteen she was in the throes of doing her GCSE exams.

‘Well, I hope you’ve asked Jaqueshia’s mother whether you can invite yourself,’ Brenda said.

Kimberly sucked her teeth. ‘She’s always got more food than they can eat.’

Then she left the kitchen.

Brenda was all too aware of the fact that her family didn’t really like this interloper who now turned up every day, plonked himself on the sofa, ate – maybe read a book – and then left. Brenda didn’t like him much. Unlike a lot of Americans she saw on the telly, John wasn’t brash or boastful, quite the reverse. He was what her mother had always described as a ‘God botherer’. Always banging on about Jesus. His parents were famously like that. Brenda didn’t really understand what kind of Christians 27they were, but she did know that they were against abortion because John had told her about it.

‘Even a child born out of wedlock has a right to life,’ he’d told her. John had very fixed views about sex outside marriage – you just didn’t do it. And he wasn’t married – which had to mean—

‘Brenda!’

She went into the living room where he was watching the six o’clock news.

‘Do you think all these people are going to go out to protest against the president?’

His voice was soft and sounded what Brenda would describe as ‘educated’. She looked at pictures of people on the TV talking about Trump.

‘Seems so,’ she said. ‘A lot of people are very angry about him coming.’

‘Why?’

She shrugged. She wasn’t that concerned about President Trump’s visit. Brenda didn’t really do politics, not like Des who could bang on about it for England. Thank God he was out at work! Just the look of Trump made him almost have a seizure.

‘I know a lot of people don’t like him,’ John said, ‘but the president is doing the Lord’s work. You know he plans to stop abortion completely in the States?’

‘Oh.’

‘Because it is like a Holocaust in our country,’ he continued. ‘Millions of defenceless babies destroyed like rubbish every year by sinful women.’

Brenda didn’t know what to say. She knew women who’d had abortions, but she wouldn’t have described any of them 28as especially sinful. Poor, frightened and dumped, yes. But she held her tongue. Now that she’d engaged Mrs Hakim to find out more about John she did feel a little bit guilty. It was going to cost a pretty penny too. But she was using her own money, cash she’d salted away over many years of car-boot sales and a couple of little ‘private’ jobs on the side, cleaning doctors’ houses. Des didn’t even know about it but then Brenda had always wanted it to be that way. After her first marriage failed back in the eighties, she and her then three kids had been left destitute. And although Des was a hard worker who really loved her, Brenda had vowed that she’d never again be left potless by a bloke.

Normally she wouldn’t have even dreamt about spending her nest egg, but this thing with John had come at her out of the blue and she felt that just for her own sanity, she had to know the truth. When her brother had disappeared down Woolwich Foot Tunnel all those years ago, the incident had slashed a scar of uncertainty in her life that had never healed. If people could just disappear into thin air, then how could anyone hope to trust anyone or anything again?

Two in the morning was such a wretched time to wake, especially if you weren’t in your own home. Mumtaz slipped silently out of the bed and made her way down the corridor to the living room. Chronus the mynah bird made a couple of strange squawking noises from his perch beside the bookcase and then turned his back. He was used to her.

Although she didn’t stay over at Lee’s place often these days, it was nice for Mumtaz to stay away from home once in a while. Not so long ago, she’d spent a lot of time here – not in the spare room but in Lee’s bed. But that hadn’t worked 29out. Not because they didn’t care for each other but because their lives were just too complicated by family, by finance, custom and religion. As a hijab-wearing Muslim woman whose faith was important to her, Mumtaz had found the questions she was asking herself about who she really was with Lee were impossible to answer. But that didn’t mean she didn’t still love him – or vice versa.

She switched on a table lamp and sat down on the sofa. Chronus grumbled softly and then closed his eyes. Although nothing had actually happened in the Woolwich Foot Tunnel that afternoon, the experience had unnerved her. According to Brenda Joseph, the last time she’d seen her brother had been when she’d watched him go into the North Woolwich rotunda. For years she had speculated about whether he’d actually gone inside at all or just legged it over to what was then North Woolwich Station and run away. He’d had, by the sound of it, little to keep him. That said, he’d only been ten. Could the story adult John told now, about being taken away by his father, possibly be true?

The notion that the father had been waiting in the tunnel for his son so that he could abduct him made Mumtaz’s skill crawl. What for? Had he maybe sold the boy to the Gustavssons? How would someone like Reg Saunders get to meet such people? Unless it was from his time working on cruise ships. But then what about the official paperwork one needed to leave one country and enter another? According to Brenda, her brother was now an American citizen called John Gustavsson. If indeed this was one and the same person, then John Saunders had been obliterated.

There were so many questions, they made Mumtaz’s head spin. Had John come to the UK with the blessing of his American 30parents? What, if anything, did he remember about his life before the US? What did he feel about his father? And, as Brenda had said, why come back after so many years away?

On the one hand, Mumtaz wanted to meet John, but on the other if she was going to observe him then that wasn’t a good idea. She hadn’t yet formulated a plan about how this job might work, but now she wondered whether she would need some help. The agency had a small group of casual PIs who came in as and when to help out, and also Lee himself had intimated that he may be able to assist. Some work, particularly matrimonial, had dropped off a little since the winter. Why this was, Mumtaz didn’t know, although she suspected it might have something to do with the UK’s imminent exit from the European Union. According to their point of view everyone was either despairing or jubilant. But even those who really wanted to leave, like Lee’s mother Rose, were worried. When nobody knew what could happen from one day to the next, anxieties about personal problems could pale into insignificance. If that is, one was not Mumtaz.

An email from her stepdaughter Shazia was causing her concern. It had said Getting active re: climate change. There’s only one issue and it’s saving the planet. Mumtaz had mailed back that she agreed, but then she’d warned Shazia about the possibility of getting arrested on any protest actions she might wish to join. Shazia had mailed back the following response:

Personal issues are unimportant. If we don’t save the planet we’re all dead. Too many people are putting their own stuff first. Not me.

And she was right. She was right and brave and she was, so far, doing brilliantly on her criminology course at Manchester 31University. But Shazia’s ultimate aim was to become a police detective. In fact, Mumtaz had been obliged to bribe the girl to study for a degree before applying to Hendon Police Academy straight from school. As far as she knew, Shazia still had that ambition. But if she got a police record at a march or a sit-in that option would be closed to her.

When Brenda Joseph had talked about her father, she had told Mumtaz that he had died at a place called Holywell in Wales. A vagrant by that time, Reg Saunders had breathed his last under the care of a convent of nuns responsible for looking after pilgrims visiting the nearby shrine. Only just over an hour away from Manchester, Mumtaz wondered whether she could both follow up on Reg Saunders’ last days and go and visit Shazia.

If, of course, her battered Nissan Micra could make the trip …

Alone without even the sound of the lift behind him re-ascending, the sound of just one of his feet moving forwards made his ears cringe. The new lighting, embedded into the ceiling, just like the old forty-watt bulbs it had replaced, worked in places. Where it was inoperative, a puddle of darkness stained the grimy floor way, its middle waste water gully stinking of piss.

People had always pissed down here. One of the kids in his class had even taken a shit on a school trip underneath the river to visit Woolwich Arsenal. The teacher had gone crazy, but all the kids had laughed. Except him. What possessed a person to take a shit in a public place? It was puzzling.

One foot down, the other proceeded it, the sound echoing off the grimy tiled walls like gunshots. He was alone and, although he’d read that these days the tunnel had panic buttons scattered 32along its length, who, realistically would or could come to help someone trapped down here with a madman? Or a rapist …

Only a few metres in he stopped to look at the grouting between the tiles. Some of the kids on that long-ago school trip had convinced him that it was only the tiles and the grouting that held back the water of the Thames. He’d looked on the occasional leaks that dribbled from the walls back in those days with horror. As the possibility of his own death had begun to dawn on him, he’d burst into tears. Everyone had laughed at him, even the teacher. But no one had taken the time to convince him that he wasn’t going to die. They didn’t care. No one did. He was a weirdo, ‘Johnny No-Mates’ and his life was worthless.

The tunnel gently dipped down to its lowest point right in the middle. Above, the Woolwich ferry plied its way backwards and forwards across the river, taking people, cars and lorries from north to south and vice versa. But it was too late for the ferry now. Unlike the tunnel it didn’t operate twenty-four hours a day. Ditto the Docklands Light Railway. So, if you wanted to travel from north to south or south to north in the middle of the night it was the tunnel or swim.

Of course, some − boys wishing to impress their girls, drunks − who chose the latter option usually died. The river was tidal and included hazardous undercurrents and it was full of filth. Toilet paper, wipes, fat, tampons and plastic, plastic, plastic. So the tunnel was the only choice, however afraid one may be. Not that he was afraid.

But on the odd occasion he saw someone else, he could see the fear on that person’s face. Man or woman, it made no difference. The thought that they could be attacked, that the tunnel could rupture, that life would end, followed them all 33like a great, black veil, dragging along the oozing floor like a curse. Separated from God, they lived lives of abject terror believing idiotic stories designed to frighten the ignorant, and if he passed any one of them on his travels he gave each one of them the evil eye. Because that was real.

THREE

‘Actually, he’s here,’ Brenda whispered into her phone. She’d been on the toilet when Mumtaz rang and was now washing her hands with the phone tucked underneath her chin. ‘He turned up for breakfast. He does sometimes.’

‘I’m thinking I’d like to talk to him,’ Mumtaz said. ‘Get to know him a little.’

‘Yeah, but aren’t you following him or whatever?’

‘Mr Arnold has allocated some of our freelance investigators to shadow him. I’m thinking you might be able to introduce me to him.’

Brenda frowned. ‘As what?’

‘As a friend from work.’

‘What? A cleaner?’

‘Why not?’

‘Well, you speak nice and …’35

‘Brenda, you must have some colleagues who’ve been to university. This is 2019, people have to do any job they can get.’

Brenda thought for a moment. There was that Tiffany who said she’d been to university, even though she talked like some tart out of EastEnders and looked like a druggie. And all the Poles had degrees.

Eventually she said, ‘Yeah. But we’ll have to meet outside the house. My family don’t know I’m doing this.’

‘All right. Do you know what he’s doing today?’

‘No. But I’m off up to Queen’s Market after breakfast.’

That was just down Green Street from the Arnold Agency’s office.

‘Well, that would be perfect for me,’ Mumtaz said. ‘Try to get him to come along with you and let me know. If you take him for a cuppa at Percy Ingle’s I’ll meet you “by chance” in there. I won’t be wearing my hijab and my name will be Aminah.’

‘Oh.’ Brenda felt confused. Didn’t all Muslim women wear the hijab whatever they were doing?

She heard Mumtaz laugh. ‘You’d be amazed the number of people who just don’t recognise me without my scarf,’ she said. ‘Let me know what time you’ll be at the market, approximate.’

Then she cut the connection. Brenda finished washing her hands and then put her phone in her pocket. She had to trust that Mrs Hakim knew what she was doing, but she hadn’t counted on her wanting to meet John. Suddenly everything felt a bit more worrying than it had. She wasn’t good at lying, never had been. But now she was going to have a conversation with a non-existent workmate.

Lee poured himself a dismal plastic cupful of tea from his thermos and looked at the front of Lorraine Pritchard’s 36house. Set a good fifty metres from the street, it was a mock Georgian affair recently painted a very fashionable shade of silver grey. Not her ex’s taste, that was for sure. Jason had been horrified when she’d had it done.

‘Looks like a fucking public bog in some park in Dagenham,’ he’d told Lee during the course of one of their meetings. It looked a lot better than that, Lee thought, but he could see why Jason didn’t like it. It was very obviously ‘on trend’. Unlike his tiny flat in Forest Gate.

Even if he’d had the cash to do so, Lee was averse to change when it came to his home. As things stood, he knew where everything was and, even more importantly, he knew that he could move everything easily when it came to cleaning. Because that was part of his ‘thing’.

Although nearly fifty, Lee Arnold was a handsome bloke – if you liked tall, dark, slim and a bit off his rocker. Prior to being a policeman, which he’d done before he’d become a PI, Lee had been a soldier. Sent to Iraq in 1990 to fight against Saddam Hussein’s Republican Guard, he had seen and experienced things that quite rightly had scarred his mind.

For years he’d hidden in booze and painkillers, but with help from a colleague, DI Violet Collins, as well as swapping one addiction for another – drugs for cleaning – he’d become as ‘well’ as he was ever going to get, which wasn’t saying a lot. But he could live with it. He’d lived with it better when he and Mumtaz had been an item but that was now water under the bridge – except when it wasn’t.

Lorraine had only half an hour ago pushed a young guy out of her front door and now, it seemed, someone else had turned up.

Judging from the car this person drove, whoever was calling was not her usual type. The boy who’d not long left had driven 37an Audi sports car. This by contrast was an ancient Escort. Perhaps Lorraine was branching out. But then Lee saw that the man who got out of the vehicle was so far away from her usual type, the thought of her bedding him was laughable.

He was also, Lee noted, her uncle.

‘Shazia!’

‘Oh, hello, Amma …’

Her stepdaughter sounded odd. Uncertain about something. And although Mumtaz knew it was important she didn’t come across as some interfering Asian auntie, she said, ‘Is everything all right?’

‘Yes …’

Did she maybe have a boy in her room? If she did that was her business. Shazia was not a religious young woman and Mumtaz wasn’t her mother – except that she was in all but name.

She said, ‘Listen, darling, I may have to come up north to work in the next week or so. Don’t worry, I won’t ask to stay …’

‘Oh, you can,’ Shazia said. ‘Of course. But I’m actually going to be coming down this Saturday. I was going to ask if I could stay …’

‘Of course you can.’

‘Only it’s the anti-Trump demo on Monday. That’s when he arrives.’

‘Ah, yes.’

Her emails of the previous evening had obviously been a prelude to this.

All part of her activism. Mumtaz approved. But …

‘Amma?’

Had she heard the hesitation in her voice?38

‘Amma, you are all right with it, aren’t you?’

‘What, you coming home? Of course!’

‘No, the whole Trump thing. I mean you can see he’s just the worst ever president, can’t you?’

‘I can,’ Mumtaz said. ‘But … But look, to be honest, I just worry about you and protesting. You want to be a police officer …’

‘Yes, I do.’

‘But you won’t be able to do that if you’ve got a criminal record. I’ve spoken to you before about this.’

There was a pause, then Shazia said, ‘I know that.’

‘Well?’

Mumtaz heard her sigh. ‘Sometimes you have to do things that don’t tie in with your ambitions. I mean, Trump’s bigger than whatever I want to do – literally. And the fact that he’s coming to our country is outrageous.’

‘Yes …’

‘We’re all going down from my department,’ Shazia said. ‘Most of us want to work in criminal justice in some capacity, but we also feel we have to do this.’

Mumtaz sympathised but she still found herself saying, ‘You do know you won’t be allowed anywhere near Trump, don’t you?’

‘Oh yes. It’s the being there that’s important.’

And maybe it was. When Mumtaz put the phone down after agreeing that Shazia could come home for the weekend, she considered her own views on the subject. She didn’t want Trump to come to London either, but she wasn’t convinced of the value of ‘just being there’ to oppose him. She opposed him and people like him all the time in her mind and, when challenged about her politics, she was very openly against 39nationalism. But she wasn’t what anyone would have considered active politically and that, she recognised, didn’t sit well with her.

The phone rang again. For a moment she wondered whether it was Shazia again, after a change of heart, but then she heard Brenda Joseph say, ‘Sorry, I’ve had to call you from the market bogs so John don’t hear. We’ll be in Percy Ingle’s in five minutes.’

‘Interesting.’

‘In what sense?’ Lee asked.

‘Well, you know I told you that no one in her family talks to Tall Tel no more? Well, that includes her, Lorraine.’

‘He’s still inside the house,’ Lee said. ‘Nearly half an hour.’

‘What’s he doing there?’

‘I dunno, but I thought I should tell you. I know you never wanted the house wired up, but there are advantages …’

‘Too risky,’ Jason said.

‘Not really. This isn’t a custody situation,’ Lee said. ‘All your kids being adults.’

‘I know, but …’

‘What, if anything, does Tall Tel do?’ Lee asked.