9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

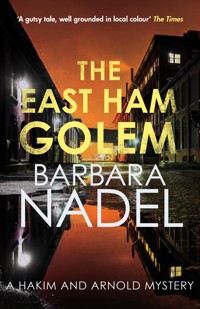

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Hakim & Arnold

- Sprache: Englisch

London, December 2019. Two young boys, Habib and Loz, are trying their luck at selling knock-off pain remedies to pensioners. But they are troubled by an encounter with a potential elderly customer and a young man with a blood-smeared face. Mumtaz Hakim wants to help if she and her partner Lee Arnold can, even though there's no way their detective agency could reasonably charge the boys. While they set about uncovering the truth behind the odd situation in the shadow of St Paul's Cathedral, they find themselves drawn into a gruesome investigation involving an old man and a newborn baby.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 428

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

WEB OF LIES

BARBARA NADEL

To my father – a London wizard.

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

There is a myth that children, particularly teenagers, do not listen to their parents. It’s as if a hidden switch trips at the age of thirteen barring all words emanating from parents, teachers and any other responsible adult. But this contention can be flawed.

Listening children exist. Those who only appear not to hear. Those who do hear, and store up what has been said for future reference and use.

Those who have an agenda … Those who have problems in need of solutions.

Mumtaz Hakim had grown up with boys like Habib Farooqi. Small, owlish behind his thick glasses, clever. He was fifteen, she’d been told, and wanted to go to medical school. Lee, when she’d informed him about the kid, had given her a look which had seemed to say ‘Asian boy wants to go to medical school – so far, so clichéd.’ But Habib’s parents were Mumtaz’s parents’ neighbours and her dad, in particular, would not have been denied.

He’d told her, ‘The boy is good. I don’t know exactly what he’s done, but he and his friend say they will only speak to you. It could be something and nothing.’

Had the private investigation organisation for which Mumtaz worked, The Arnold Agency, not been hard up for work, she would have told her baba that she didn’t have time. But, after a summer of too much work, they’d now hit a fallow period.

Lee Arnold, her boss as well as her romantic partner, had said, ‘But we can’t charge a fifteen-year-old kid! Where’s the money in it?’

There was none. But with a caseload that contained nothing but process serving – delivering court documents to defendants – for the foreseeable future, Mumtaz was bored.

As she looked at Habib and his friend Lawrence, she couldn’t actually see a crime of the century situation developing, but she was prepared to hear the kids out.

She said, ‘Start at the beginning. Tell me everything. If you don’t, I won’t be able to help you. Let’s start with the cream. Why did you make it? Was it to make money for something specific?’

The boys, one small for his age, blinking behind his specs, the other a lanky white kid with spots, looked at each other. Then the white boy said, ‘It’s all my fault. Habib was just trying to help me out because I’m a fuck-up and he’s a mensch.’

Before her parents had emigrated to Spitalfields from what in the 1960s was then East Pakistan (now Bangladesh), Brick Lane and its environs had been a Jewish area for decades. People usually spoke Yiddish back then. In fact, it had seeped its way into the language of the local population who lived alongside the Jews. Had Lawrence Williams’ family been one of those or had they been, at one time, Jews themselves? Whatever, it was unusual to hear the word ‘mensch’, meaning good friend, on the lips of one so young.

‘Tell me about it anyway,’ Mumtaz said. ‘I won’t tell anyone unless you give me permission.’

‘You won’t tell his dad,’ Lawrence or ‘Loz’ said, nodding his head towards Habib.

‘No.’

Ali Riza Farooqi was a respected local pharmacist. Not known for anything like bad temper or rudeness, as far as Mumtaz knew he was a devoted husband and doting father to his children Iqra and Habib. Her baba was always going on about how those kids were spoilt.

She saw Loz gulp and then he said, ‘Kym told me she was on the Pill, but she weren’t.’

Mumtaz didn’t know what she’d expected the boys to say about why they’d suddenly taken to what had been basically snake oil salesmanship, but this had not been amongst the options she’d considered.

‘Kym?’

‘Fam with benefits, weren’t it,’ he said.

Habib translated. ‘Loz was going out with Kym. She’s a girl at our school.’

‘OK, and …’

‘She says she’s pregnant,’ Loz said. ‘She’s sixteen but she says it’s mine and she wants this phone and …’

Habib said, ‘She told him if he doesn’t get her the new Samsun’ Galaxy, she’ll tell her dad.’

Mumtaz, at thirty-seven and with one marriage already behind her, wasn’t easily shocked, but she hadn’t been expecting something like this. The boys had apparently been selling a home-made pain control cream called capsaicin. Used by a lot of elderly people to counteract arthritic pain, it had been in short supply since September. Habib’s father had apparently sounded off to all his customers about it. He was very sorry, but there was a supply issue and he just could not get hold of it. Habib had listened to this for some time before he’d actively sought out the recipe for a home-made version of the cream online. It had taken Loz’s ‘problem’ to spur him into action.

‘Kym’s dad’s a cage fighter,’ Loz explained.

The only thing Mumtaz knew about cage fighters was that they fought, bare knuckle, in cages and that one of media star Katie Price’s many husbands had been one. Loz was probably right to be scared. If indeed Kym was pregnant.

Remembering the little her father had told her about the boys, Mumtaz said, ‘This capsaicin cream, you sold it locally? Door to door? On the market …’

‘Door to door,’ Habib said. ‘But not locally. In the City.’

‘Lot of old people round here,’ Mumtaz began.

‘Who all know my dad!’

This was true.

‘We only charged a pound for it,’ Habib continued. ‘And I told them if they didn’t put it in the fridge it would go off.’

‘You told my baba you mixed cayenne pepper with ghee,’ Mumtaz said.

‘Yeah.’ Habib dropped his head.

‘Yeah.’ Loz followed suit.

‘So, OK …’ Mumtaz flicked the loose end of her headscarf away from her face and said, ‘And this you sold in the City, as in the Square Mile. Why? Very few people live there, it’s all offices.’

‘No it ain’t,’ Loz said. ‘Not where that kid lives.’

‘This is the boy …’

‘Covered in blood, yeah,’ Habib replied. ‘From his mouth I think, maybe. Certainly all down his front.’

ONE

‘Carter Court,’ Lee Arnold said, ‘looks like somewhere merchant bankers might live.’

Mumtaz, who was accustomed to Lee’s Cockney rhyming slang, said, ‘So, low opinion of the wealthy …’

‘Maybe, maybe not,’ he said. ‘I’ll give you not all wankers are merchant bankers, although a lot probably are.’

‘But all merchant bankers are?’ she asked.

He smiled. Swearing still sounded weird coming out of Mumtaz’s mouth. When he’d first employed her she’d been a timid, covered Asian widow lady with a psychology degree. Now, although the headscarf and the degree remained, she was a confident, sassy woman with a sharp sense of humour. He was also in love with her.

Lee was looking at Street View on his computer screen.

‘Just up Ludgate Hill from St Paul’s,’ Lee said. ‘Flats mainly.’

‘The boys said this kid was in a house. An old one.’

Lee frowned. ‘Most of the old places round there were flattened by bombs during the war,’ he said. ‘Must be one of the few that survived.’ He pointed to the screen. ‘Maybe that place beside that pub.’

Mumtaz peered at the screen. There was a tall, thin building next to a Victorian pub.

‘Mmm.’

Lee turned his chair round to face her. ‘So what happened?’ he said.

‘The boys say they had been to some of the flats and were surprised to find that most people were out,’ Mumtaz said.

‘You’d think they’d know …’

‘They’re both a bit other-worldly,’ Mumtaz interjected. ‘Even Loz. I think we imagine that kids living so close to the financial centre are clued in about it, but loads of them aren’t. I grew up there myself. The Square Mile might just as well have been on Mars.’

‘OK.’

‘They approached what they called an “old” blue door.’

Lee looked back at his screen again. The doorway to the house next to the pub was painted the shade of blue that always reminded him of launderettes. Watery and faded.

‘And then …’

‘And then,’ she said, ‘before they could actually knock, they heard someone running.’

‘OK, running where?’

‘Towards the front door. He, as it turned out, opened the door, breathless and bleeding. Blond, so the boys said, sixteen-ish.’

‘Where was he bleeding from?’ Lee asked.

‘Not sure, but Loz reckoned he had a cut lip. There was blood on the jumper he was wearing.’

‘Kid with a nosebleed?’

‘I put that to them,’ Mumtaz said, ‘but the boys told me they didn’t think that was the case. This youngster, according to them, looked scared, he had bruises on his face and he said “help me”. There was an elderly man watching him from the other end of the hallway.’

‘Meaning what?’

‘Meaning, they thought at the time, that the man was preventing the boy from leaving. As they had approached the front door, he, the boy, was clearly on his way out. He saw Habib and Loz, it shocked him, and so he stopped.’

‘He didn’t push past them to get out?’

‘No, just stood, looking at them, asking for help.’

‘With this older bloke at the end of the corridor?’ Lee said.

‘Yes. Looking at them apparently. Then, according to the kids, the boy shut the front door in their faces, but he was shaking when he did it. And that was that.’

His granddad had laughed when Jordan had said his ambition was to join the City of London Police. He’d seen them at the Lord Mayor’s show when he was five and had wanted to be one until he actually joined in 2014. His granddad had continued to laugh at him then and continued to laugh at him now.

‘Taller’n other coppers, the City Police always was, back in the old days,’ the old man said whenever he saw Jordan in his uniform. And Constable Jordan Whittington wasn’t tall. Not that his height was the point. What really worried his granddad was that his grandson was a black copper in a predominantly white city. Granddad Bert didn’t really ‘do’ the police and couldn’t understand why Jordan had wanted to become a copper. The boy’s parents, Bert’s son Derek and his girlfriend Gina, had been junkies and had subsequently been arrested by the police on numerous occasions. They had not been treated well, especially Gina, Jordan’s Afro-Caribbean mother. Just sick kids the both of them, Bert often felt. Poor kids.

A few months after Jordan’s birth, when they could no longer look after their child and feed their habits, Derek and Gina had put the child in his Moses basket on Granddad Bert’s doorstep in Bethnal Green. Then they’d run away, leaving their newborn with a pensioner with a dodgy leg.

Derek had been a junkie since he was in his twenties, and by the time Jordan was born, Gina was too. The old man had heard on the grapevine that his son had died by 1999, and none of Gina’s God-fearing West Indian relatives had heard from her in decades. For just shy of twenty-six years, it had been the old man and Jordan against the world. And Jordan wished that his crusty, arthritic old granddad was with him now.

Long, long ago, back in the mists of time, what was now the City of London Police had been divided into ‘watches’ – the ‘Day Watch’ and the ‘Night Watch’. Patrolling either in the day or at night, the Watches sought to protect both the residents of the Square Mile and the financial institutions and legal Temples within its boundaries. They were not and had never been part of the Metropolitan Police and, as well as encompassing almost untold wealth within their patch, the City Police were also responsible for some key national monuments – like St Paul’s Cathedral.

That old copper’s friend, the Observant Drunk, had tipped them off in the early hours of that morning. On his unsteady way from his office Christmas Party in Hatton Garden to an assignation with a pole dancer called Minx at the Polo Bar on Bishopsgate, Ryan Faulks had noticed someone doing some late-night gardening in St Paul’s Churchyard. And because there was a police station just down Bishopsgate from the Polo Bar, Ryan had done his civic duty and reported it just before he met up with and paid for Minx to have a Harvey Wallbanger and a Full English. Two hours later, Jordan and an almost unconscious Ryan had been sent over to St Paul’s Churchyard to check it out. It was four in the morning by that time and Ryan wasn’t happy.

What they’d found had been grim beyond either of their imaginings.

‘So tell the coppers,’ Lee said.

They were both sitting on the steps of the iron staircase outside their office on Green Street, Upton Park so that Lee could have a fag.

‘The kids were trying to sell hooky arthritis cream,’ Mumtaz said.

Lee sighed. Then he said, ‘And this was the day before yesterday?’

‘Yes.’

‘So what can we do about it?’

‘Have a look,’ she said. ‘Find out who lives there and what they do. Find the boy and see whether he’s OK.’

Lee puffed. ‘What do the kids think was going on?’

‘They’re afraid the boy is being held against his will,’ she said.

‘What, in a sort of paedo kind of a way?’

She shrugged. ‘I don’t know. But Lee, if someone is brutalising this boy then it has to stop.’

‘Agreed, but we can’t just go stomping in there like the US Cavalry.’ He stood up. ‘Anyway, I have to get out to Romford.’

Process serving. Mumtaz had two herself; one in Barking and another just up the road from their office.

Before he left to go to Romford, Lee said, ‘I’ll have a think about those two kids of yours. See you back at the flat?’

She said that she would. Whether or not she’d stay the night, Mumtaz didn’t know. But if she stayed with Lee he always did the cooking, which was fine by her. Now that her stepdaughter Shazia was either at university or, when in London, staying with her boyfriend, Mumtaz rarely had either the need or the inclination to cook herself. Her own mother, a traditional Bangladeshi amma, was quite bewildered by the whole situation.

But then so, in many ways, was Mumtaz. Falling in love with Lee had come as a shock and she was still working out how that might or might not pan out in the future. For the moment things were on an even keel. They led fairly separate lives for much of the time, while her mother chose to believe that her daughter and her white boyfriend had an entirely platonic relationship. It wasn’t ideal but it was way better than the abusive marriage she’d had before. Shazia’s father, Ahmet Hakim, had been a violent drinker addicted to gambling and the company of gangsters. Now he was dead.

Mumtaz put Ahmet from her mind and got on with her day. What, she wondered, did Lee have in mind with regard to the two young boys from Spitalfields?

He’d seen that SOCO tent erected over outdoor crime scenes a few times during the course of his career, but Constable Jordan Whittington always felt cold whenever he saw one. There was usually a dead body underneath it and in this case, that was a certainty.

Ryan Faulks, the thirty-five-year-old Observant Drunk who had led Jordan to the scene in the early hours, had thrown up what must have been several pints of wine and at least half a bottle of vodka when Jordan had moved the pile of earth to one side and seen that hand. At first he had thought that it belonged to a doll.

But dolls were not pliant like that. Dolls didn’t have bruised faces.

Dolls, unlike babies, never die.

‘The house where you saw the boy,’ Mumtaz asked, ‘was it next door to a pub called The Hobgoblin?’

Mumtaz had calculated it had to be lunchtime when she called Habib Farooqi on his mobile. He’d answered almost immediately.

Habib had thought for a moment when she’d mentioned the pub. Yes, he’d seen a pub, but what it had been called was another matter.

‘Was the front door of this house blue?’ she continued.

Another pause and then he said, ‘Yes. Are you going to look into it then, Mrs Hakim?’

She was. She knew she was. But would Lee be on board with her? And if he wasn’t, what then?

Eventually she said, ‘I’m not sure at the moment, Habib.’

‘Oh.’

‘But I’ll call you tomorrow morning and let you know without fail. Habib, do you know whether Loz’s girlfriend is really pregnant?’

‘She says she is,’ he said. ‘Why would she say that if she wasn’t?’

Mumtaz sighed. There had been a girl at her school who had told everyone she was pregnant when she hadn’t been. Diane something or other. She’d been going out with a boy called Jayden who had a stall in Spitalfields Market with his brother. They sold handbags, which had been part of the appeal. Nothing had ever come of Diane and Jayden’s brief affair, and word at the time had been that Diane hadn’t even got a fake Prada bag out of it. Mumtaz changed the subject.

‘Look, can you email me a list of things you remember about that boy and where he lived?’ she said.

‘Can’t we do it on WhatsApp?’ he asked. ‘I mean then I can, like, write things down when I think of them?’

He had a point, even though Mumtaz was loath to admit it. Shazia communicated almost exclusively via apps these days; Mumtaz wasn’t a fan. She decided to stick to her guns.

‘You’ve got my card so I’d prefer it if you emailed me,’ she said. ‘Just sit down for a few minutes and try to remember what you saw. Even better, do that with Loz – he may remember things that you don’t and vice versa.’

‘OK.’

But he didn’t sound pleased about it.

Tough.

TWO

The six o’clock news was on and so Chronus, Lee Arnold’s mynah bird, had turned his back on the TV. He’d always been a bird with good taste. Over the years since his old friend and colleague Detective Inspector Vi Collins had given the bird to him, Lee had taught him to squawk ‘I’m Forever Blowing Bubbles’ as well as a whole list of West Ham United team line-ups from the 1980s and 90s. He could also swear.

‘Fuck.’

Chronus repeated Lee’s expletive as his master sat down in front of the television.

Often stories about babies – usually newborns, found dead in parks, in the street or in rivers – passed him by. Behind these tragedies were usually fearful or ashamed young women, giving birth in secret and then abandoning their infants out of fear. Rarely was infanticide involved. But in this case there appeared to Lee to be an implication. He’d been a copper, he knew how they put things. It didn’t always mean that foul play was involved when cause of death was ‘unknown’, but it could do.

The child’s body had been found in the churchyard of St Paul’s Cathedral, sometime in the early hours of that morning. Police had been alerted by a member of the public who had seen someone digging in the churchyard in the middle of the night. Who that had been and why he or she had been doing it could be entirely unconnected to the discovery of the child’s body. But it seemed to Lee that the idea of digging in the night and concealment of a body went rather well together. It was also in a part of London he was currently thinking about.

Mumtaz, like him were he honest, bored easily and all the process serving with the occasional foray into observing potentially unfaithful husbands was doing her head in. Habib and Loz’s bloodied boy was probably, sadly, a case of domestic abuse, but he knew that Mumtaz was dead set on doing it even though there was no money in it at all. That went against every cell in Lee’s body, but …

His dad had knocked them all about when Lee had been a kid. Him, his brother, their mum. A violent drunk, he’d made their mum fearful; Roy his brother had copied their old man while Lee had got out as quickly as he could by joining the army and then the police. Kids being brutalised by their parents was something that was still overlooked in spite of social service reforms, in spite of campaigns against it by celebrities. Did Lee feel more angry about that than he did about losing a bit of money?

He knew the answer to that and picked up his phone.

‘Was it a win?’

Bert Whittington put the kettle on the stove and turned to face his grandson. Jordan and the old man had a running joke between them that every day the young man wasn’t called a ‘cunt’ by someone or other, public or fellow copper, it was a ‘win’.

Jordan flopped into a chair at the kitchen table and said, ‘It was a win. If you can call a day when you find a baby murdered a “win”.’

The old man sat down opposite. Jordan had called home at ten that morning to let Bert know that he’d not be coming home for some hours. He’d explained why, but briefly.

‘You sure the kiddie was murdered?’ Bert asked.

On the stove, the kettle began to ‘sing’ a little as the gas flames licked up its ancient, battered sides. Bert didn’t ‘believe’ in electric kettles, just like he didn’t ‘believe’ in the Internet or mobile phones.

‘Yes.’

‘Tell me about it?’

‘I can’t,’ Jordan said. ‘You know that.’

The old man shrugged. In reality Jordan would have liked to tell Granddad Bert to get it off his chest, but he knew he couldn’t. The details of the case were under wraps for the time being, and quite rightly so. It had been horrific. A newborn the doctor had reckoned, stabbed. Not just once, five times. A girl, it was mixed race, like Jordan himself. To do that to any living creature was an abomination but with racism on the rise, he couldn’t shake off the possibility that had been at least part of the motivation.

Bert changed the subject. He said, ‘Your Nana Willi called to speak to you. I think she’d like you to go over there.’

The mother of Jordan’s mother, Wilhelmina Banks, or Nana Willi, called often and usually about the same thing.

‘She wants me to go to church,’ Jordan said.

‘So go with her,’ Bert said. ‘She’s a little old lady as wants to parade her eldest, handsomest grandson to her mates.’

‘She wants me to be “saved”,’ Jordan said.

Nana Willi and her family were all born-again Christians who attended a huge, mainly West Indian, church in Brixton. Jordan’s cousins were all very involved in the church and, as a family, they did a lot for the local community. That bit of it, Jordan could get and he was very proud of them. It was just the religion side of things he couldn’t come to terms with. What he saw almost every day, and especially in light of this baby killing, seemed to Jordan to mitigate against the possibility of a caring, loving God. Also, with Granddad Bert as his guardian, he’d not exactly been brought up with any real concept of an Almighty.

The old man sighed. ‘So go to make the old girl happy,’ he said. ‘You don’t have to go full-on happy-clappy Praise-the-Lord.’

‘I do,’ he said. ‘They expect it.’

‘So what does it hurt to do it for their sake for once?’ Bert said.

‘It doesn’t, but …’

‘But what?’

The kettle boiled and Bert poured the hot water into a teapot. He still used tea leaves as well as a non-electric kettle. Jordan sometimes thought that the way he clung to the past was probably something to do with wanting his son back as he’d used to be when he was a kid, before smack.

‘She tries to hide it, but I know Nana Willi blames my dad for my mum’s addiction,’ Jordan said.

‘And she’s right,’ Bert replied. ‘Our Derek did get her into it.’ He looked choked up for a moment. ‘Used to take Gina with him when he went to score.’

‘She could’ve said no …’

‘Nah.’ The old man shook his head. ‘You never knew your dad. People never said no to Derek. Charm the fucking birds out the trees. And she loved him – up until they both got heavy into heroin, then she only loved that.’

They sat in silence for a little while then, until Jordan changed the subject. After that he drank his tea and went up to lay down for a while. Alone in his bedroom he tried but failed to get the little girl’s face out of his mind. Then he cried.

Mumtaz took the Tube to St Paul’s and then she went for a walk. Elated by the news that Lee was going to take the two boys’ case, she was going to have a look at the lie of the local land. It was dark and it was cold but, when she got out at St Paul’s, the Square Mile was still buzzing with activity. Not everyone wanted to just get home after a day at the office, and all the bars and pubs she passed on Ludgate Hill were full. There were also a lot of police in evidence. A dead baby had apparently been found in the churchyard. Mumtaz shuddered at the thought. Looking to her left, she walked past the entrance to the cathedral as well as the far from flattering statue of Queen Anne on her right, until she came to Creed Lane. This, if her GPS was correct, would then lead her on to Carter Lane which in turn, if rather hazily, would then lead into Carter Court.

As soon as she turned off Ludgate Hill, Mumtaz felt, and heard, the change. Not only was Creed Lane narrow, it was also silent. Tall buildings – some four storeys high, some five – lined a thoroughfare of thin pavements and a cobbled road. Some of the buildings were clearly old, others of indeterminate age. Lee had told her that this part of London had been heavily bombed during World War II as the Nazi war machine attempted to destroy the cathedral. But some buildings had survived; she could see what looked like an Edwardian pub at the end of Creed Lane.

As she moved forwards, Mumtaz experienced what she interpreted as a chill coming from these buildings. They were dark and apparently empty, and a thin mist had begun to cover some of their roofs, obscuring any High Victorian embellishments that may have been apparent during the hours of daylight. She recalled the famous wartime photograph of St Paul’s Cathedral rising up out of the smoke caused by incendiary bombs, and pulled her coat tightly around her body. Hundreds, maybe thousands of people had died in this area, not just in World War II but over the many centuries this part of London had been the centre of both faith and commerce. Of course the narrowness of the street, allied with the incoming mist and the darkness, contributed to her feeling of disconnection to the world. But she also experienced a haunting sensation, and when a man came towards her out of the mist she wondered whether he was real. Wearing a long brown overcoat and a flat cap, he looked like a character from a Dickens novel.

At the end of Creed Lane was Carter Lane which stretched to both her left and right. It seemed, according to the GPS, that she should go right and so she did. There was a pub on the corner, but it wasn’t called The Hobgoblin. Looking in the windows she saw a lot of people inside drinking and apparently chatting, but there was almost no noise. When she’d lived back at home in Spitalfields some of the old white people she knew had reckoned that the area around Christ Church was haunted. Her amma had a friend called Betty who told her that back in the old days there had been something called a charnel house in Christ Church’s cemetery. Harking back to a time in the late eighteenth century when London’s population was exploding, a charnel house was a place where the bones of the long dead were stored after they had been dug up to make way for more recent corpses. It was long gone now, but Betty reckoned that ghosts still remained. She said that every time she walked past the church when she had her son Tom in his pram, the kid would scream and cry in fear.

As the mist thickened, Mumtaz walked on. But then she stopped. Not because she couldn’t go any further, but because the hairs on the back of her neck were standing up. Someone was following her.

People didn’t chat in The Wren. Not on the stairs, not in the lift, not in the corridors. Putting the recycling out round the back of the block would only spark the odd smile if you were lucky. Most of the time those putting out their recycling combined it with jogging or cycling or ‘breathing’. One thing that was always involved, however, was a huge mug of some posh coffee or other.

Danielle actually liked coffee. But not like that. Not clasped in some weird leather mitt by some grey-faced, Lycra-covered bloke on a push-bike that cost more than her dad’s car. Whether or not they were actually judging you, they and their floral-print women always looked as if they were. A lot of how they were was to do with wanting to have the bare minimum, or so Henry said.

‘It’s all about being greener and more socially responsible,’ he’d said when she’d asked him about these cycle-helmeted warriors who frequently pushed her aside in Tesco Metro as they attempted to reach the oat milk. ‘They’re lovely people.’

And of course he would say that, because he was one of them. That had become very apparent the first and only time Danielle had invited their immediate neighbours for ‘supper and drinks’ a month after she’d moved into The Wren. Zander and Pippa, the neighbours had been called. He’d rocked up sweaty and encased in Lycra while she wore the regulation flowery dress and hand-made espadrilles.

Henry had cooked. Some vegan thing that had been very nice in spite of the tofu. Their guests had kept going on about it, she remembered, about how you could have it smoked now. In fact, provided you had the right equipment, you could smoke it yourself. Who knew? All Danielle could really recall about that evening was the way that Pippa kept on looking at her.

Would she and Henry be together were she not pregnant? Probably not. She’d been his PA for two years before their affair. Tragically they’d got together first at the Christmas party, then he’d cooled, then after one drunken evening in El Vino’s they’d had sex al fresco in the Inner Temple and that was when she’d got pregnant. Of course he’d asked her to get rid of it, but she wouldn’t. Then, after a period of reflection at his parents’ villa in Greece, he’d asked her to move in. Her mum had told her she was mad. But this wasn’t yet a permanent arrangement – more a trial period to see whether they could become a couple.

Looking out of the front window into the darkening street below, Danielle thought about this. Of course she’d had to leave her job. Henry was a partner at Blizzard Solicitors LLP – along with his father and a cousin. Once the baby was born, Henry said, she might be able to go back. Danielle hoped so. She’d enjoyed her job; she’d liked the people she’d worked with and her position of ‘smart common girl done good’. But, although she’d never in a million years thought she’d feel like this, she missed being at home in Dagenham with her parents and her sisters. Though not stylish like Henry’s apartment, her old house had been full of life. This was like living in a tomb.

It was then that she saw a figure running down the street. Not in the usual way the joggers ran, but full pelt as if he or she was running away from something or someone. She couldn’t see anyone behind the running figure. But then it was foggy. Fog tended to gather in these narrow, steep-sided streets. The figure looked up and behind itself and through a fleeting glimpse of its face, she could see that it was a woman.

‘Where are you?’ Lee asked.

‘Blackfriars Tube,’ she said.

How she’d ended up there, Mumtaz didn’t really know. Running down narrow streets, choked with mist, guided by the odd street lamp, she’d arrived at Blackfriars Tube Station, slathered in a weird, cold sweat.

‘Did you see anyone?’ Lee continued.

‘No. It’s foggy here. But I heard footsteps behind me.’

‘Could’ve been the echo of your own footsteps. See people about?’

‘No,’ she said. ‘I’m not an idiot. I think I’d know the difference between an echo and footsteps behind me. I’m telling you, someone was there.’

‘That’s a really old and spooky bit of the City,’ Lee said. ‘Everything’s haunted up there.’

Mumtaz lost her temper. ‘I don’t believe in ghosts, as well you know,’ she said. ‘No, this was a person and he or she had ill intent.’

‘How do you know that?’

She pulled a face at her phone. Sometimes he could be such a moron.

‘Piloerection,’ she said.

‘You what?’

‘When body hair stands up in response to cold or fear,’ she said. ‘It’s a hangover from our evolutionary past.’

‘I thought you didn’t believe in all that.’

‘That’s irrelevant!’ she said. ‘It’s a fact, a thing, and it happened to me just now!’

Getting into where Islam stood on natural selection wasn’t something she wanted to do. What she wanted from Lee was a bit of validation.

She said, ‘I’m not saying I was so scared only the comfort of your voice can make me feel better.’

‘I know. You’re an independent—’

‘I didn’t dream it or make it up, Lee,’ she said. ‘I accept that at least some of what happened was mediated by my own consciousness, but not all of it. I’m telling you, I was scared and I don’t get scared by nothing. For all its posh flats and quaint corners, I don’t like the area around the cathedral, it’s …’

‘What?’

She shook her head and then she said, ‘Maybe it’s something to do with how old it is, how much time it has absorbed, how much blood …’

‘Did you find the house in Carter Court?’ he asked. Lee couldn’t really manage too much esoterica.

‘No,’ she said.

‘No?’

‘I looked. Of course I did, but what with the mist and the footsteps … I kept either missing it or going round in circles. I need to come back in daylight.’

‘We need to come back in daylight,’ Lee interjected.

‘I thought you didn’t want to get involved,’ she said.

‘You know how I feel about this pro bono work, but that don’t mean I’m not interested,’ he said. ‘Anyway, look, you want me to meet you at Forest Gate?’

He meant the train station. She lived further away from it than he did and a walk back to her place at night could be a slightly unnerving affair. However, albeit in a very secondary way, he was angling for her to maybe come back and stay at his place. But before she could answer him, he realised this and said, ‘No strings …’

Loz had only ever seen Kym Franks’ dad twice before, and that had been enough. Now he thought he could hear him when Kym phoned him that night. Something or someone very loud was swearing and hitting stuff somewhere in the background. Loz cringed. If that old knuckle-dragger ever got hold of him in anger, he’d snap his head off like a ring-pull.

‘It’s the phone or I tell me dad,’ Kym said. She sounded as if she was putting on lipstick. She probably was. Kym had made it clear to everyone at school that she was working on becoming a beauty influencer. Companies sent you lipsticks and mascaras and stuff to try and comment about online. Loz had once been into some games influencer kid about a year back, but Habib had told him that the kid didn’t know what he was talking about. And Habib knew stuff.

Loz, who had to his credit said this before, kept his voice down so that his mum didn’t hear. ‘He’ll have to find out in the end …’

‘Not if I have an abortion,’ Kym said. ‘Which, by the way, you’ll have to pay for too.’

Loz felt his face drain. ‘How much?’

She paused for a moment and then said, ‘A grand.’

‘A grand!’

‘Everything costs,’ Kym said. ‘You think I’m going down some rough old clinic down Bow or somethin’? You need to spend some drip on your woman, you get me?’

‘Yeah, but the phone’s a grand! I ain’t got no drip, man!’

‘You got a week,’ Kym said.

‘Yeah, but …’

‘Your rents work, innit?’

Rents were parents, of which Loz had only one and all she got was minimum wage. Kym was the one with two working parents – her dad in the cages and her mum as a hairdresser in East Ham. It was also said that her dad did the odd ‘job’ for certain local ‘faces’. Even kids like Loz knew that chucking weighted corpses into the Thames wasn’t a service that came cheap.

‘Kym!’

It was that terrible roaring voice again!

Loz heard Kym say, ‘Yes, Dad?’

‘Get off that fucking thing for five minutes, will ya? Over a ton you spent of my money on that fucking thing, last month!’

It sounded as if she moved to another room. She said, ‘I gotta go or he’ll lose his shit. One week you got. Say less?’

Say less? She was so into all the latest street talk. Really, she was a dick. Say less meant to understand, and he said that he did and then cut the connection.

Not only hadn’t he been able to talk to her about whether she was really pregnant – of course she’d say she was, but Mrs Hakim had told him about hearing doubt in her voice. He thought he knew what she meant. But he hadn’t managed to tell her about the house he and Habib had been to and the bleeding boy. She’d understand they had to do something about that before her phone or anything – wouldn’t she?

Loz felt a shiver run up his back as he realised that Kym wouldn’t give a shit.

THREE

More than anywhere else in London, the Square Mile was probably the best place to be if a person wanted to disappear. This was firstly because few people lived there and secondly because, in the twenty-first century, those that did live in the City had no notion of community. Many were young, professional types who had chosen to live near their places of work before migrating out to Surrey or Hampshire to become commuters, long-distance parents and owners of executive housing.

Mumtaz and Lee had waited until 10 a.m. to go to St Paul’s the following morning. In spite of everything she’d told herself about how she could easily get herself home from Forest Gate Station in the dark, Mumtaz had been glad that Lee had come to meet her. Her experience the previous night had unnerved her and so she ended up staying over with Lee. Although they didn’t make love, they both found sleeping in the same bed comforting and relaxing.

Carter Lane and its environs were totally comprehensible by day, and within minutes Lee had guided them to Carter Court. The place was accessed down a narrow alleyway, and Mumtaz could both see and not see how she had missed it. Exactly where the GPS had indicated, it was nevertheless a place easily overlooked, especially in the mist.

On two sides, Carter Court consisted of characterless, some would say discreet, low-rise apartment buildings. A third side – the entrance to the court – was what remained of what appeared to be an old agricultural building – that or the remnants of a coaching inn. The fourth side, and what came into view first when one entered the space, was an ornate Victorian pub called The Hobgoblin and an old house next to it which had a blue front door.

Lee looked into the court, looked at Mumtaz and then said, ‘Easy when you know how.’

She elbowed him in the ribs and said, ‘Sod.’

He took her hand and they entered Carter Court. Just briefly, Mumtaz saw a face at one of the top windows of the house, but then it disappeared. It was such a cliché she wondered whether her brain had simply created it for her own amusement.

The pub, which had long ago been painted a dirty cream colour, had mouldings of what looked like bunches of grapes and horns of plenty picked out in black. There were sconces above the large, partially obscured windows used to hold gas jet flames or even perhaps flaming torches. Lee went up close to look through the windows. Mumtaz said, ‘What’s it like?’

‘Reminds me of the old Ferndale in Cyprus,’ he said.

Mumtaz said, ‘What the hell are you talking about?’

‘You know Cyprus?’ Lee said.

‘Country in the Mediterranean, yes.’

‘No, Cyprus in Newham,’ he said. ‘Down Beckton, you know!’

She didn’t, but then the southern part of the London Borough of Newham was a bit of a mystery to a lot of people, unless they actually came from the area. Lee, who had been born in nearby Custom House, knew it well. He said, ‘It’s on the DLR.’

Mumtaz vaguely remembered seeing a station called Cyprus on a map.

Lee continued. ‘Cyprus was an area built for dock workers,’ he said. ‘There was a pub there called The Ferndale. Flats now, I think. Anyway, back in the eighties it was still a pub. My old man used to go down there, it was his sort of place. Lot of old boozers, sticky carpet, Union Jacks.’

‘And it looks like that in there?’ Mumtaz asked.

‘Yeah.’

‘Seems a bit weird in an area like this?’ Mumtaz said. ‘Do you think it’s sort of ironic?’

Lee laughed, a weird burst of sound in an otherwise silent place.

CID were on the dead baby case now. In charge was DI Scott Brown. Jordan knew him. Didn’t like him. Fancied himself as some sort of British version of an FBI G-man – all sharp suits, casual sex and the St George’s flag up his arse. Everything Jordan wasn’t.

Granddad Bert was still in bed when Jordan got up, and so he took the old man a cup of tea. It was his day off and he didn’t have to rush about getting ready for work.

‘What you up to today?’ the old man asked him.

‘Dunno,’ Jordan said.

Although he did. During the course of the previous day one of the officers who had turned up in St Paul’s Churchyard had been Sergeant Wilkinson. A tall, uniformed officer, Colin Wilkinson seemed to have been around for ever. Jordan had once asked a colleague whether ‘Wilko’ was ever going to retire. He’d received the answer, ‘No.’

Wilkinson, also on leave that day, had told Jordan he was going back to the crime scene to have a ‘bit of a think’. And while Jordan hadn’t taken that as an invitation to join the older man, he knew that Wilko, at the very least, wouldn’t tell him to fuck off.

‘You wanna go down Brixton,’ Bert continued, as he poured his tea from his cup into his saucer and slurped it into his mouth. ‘Your grandma’ll—’

‘Oh give it a rest, Granddad!’ Jordan said.

Bert, who knew Jordan almost as well as he knew himself, said, ‘Heard you crying last night.’

‘Yeah, well …’

‘Say what you like about Willi and her family but they’re a force of nature, the lot of them,’ he said. ‘Willi’ll stuff you full of food, you’ve got your cousin Ann dancing through life and Gabriel, if he’s got a second to spare. They ain’t all happy clappers.’

He was right. His cousin Ann was a student at the Royal Ballet School and her brother Gabriel was a solicitor. To be fair the rest of the family were, in one way or another, in ‘ministry’, but then that didn’t make them bad – exactly. Just – incomprehensible.

‘Anyway, I need to do some Christmas shopping,’ Jordan said.

‘Well don’t bother getting nothing for me,’ the old man said. ‘What I ain’t got I don’t want or need.’

He always said that, every year. Jordan smiled and said, ‘We’ll see. Anyway, look, I’ll be out for a few hours. Anything I can pick you up?’

Bert thought for a moment and then said, ‘Skate. Middles if you can find ’em. I could do with a nice bit of skate.’

A man plus his bike broke the silence. On the thin side of slim, he wore an all-in-one cycling suit and a helmet with a camera on the top. He walked over to Lee and Mumtaz and said, ‘Pub doesn’t open until midday.’

‘Oh, don’t matter,’ Lee said. ‘We’re just having a look round the area.’

The man swung his leg over the bike and prepared to mount. He was probably in his thirties although his face was rather heavily lined, gaunt almost.

‘Looking to buy somewhere?’ he asked.

Lee, for the sake of simplicity said, ‘Maybe. What’s it like?’

‘Convenient for the City,’ the man said. ‘Quiet. Except for that place.’

‘The pub?’

‘Last outpost of the original residents,’ the man said.

‘What do you mean?’

He sniffed. Then he said, ‘You’ll see,’ and cycled off.

Lee looked at Mumtaz and said, ‘Charming.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘You clock him?’ Lee said. ‘Posh bike, all the gear, voice courtesy of the Home Counties. Christ, I expect a few old costers get together in the boozer of a Saturday night. Few roll-up dog-ends out by the bins, the odd brown ale empty on the cobbles. I know his type. Probably wants this pub shut down to make way for an artisan coffee shop or some posh baker’s where they only sell sourdough.’

‘Wow, but your working-class cred is up and running today!’ Mumtaz said.

‘Well …’

She took his arm and they began to walk out of the court.

‘Anyway,’ she said. ‘Now we know the place exists, what do we do?’

‘What do you do, you mean,’ he said. ‘I’m stuck with the process serving while you help those two lads of yours.’

‘They’re not mine!’ she said. ‘And anyway, if the boys are right then we have to get a move on. There could be a child in trouble right here, right now.’

‘There could,’ he said. ‘But if they was that worried your lads would’ve called the police.’

‘And expose Habib to the disappointment of his father? You don’t know Asian families at all, do you?’

He ignored her. ‘I s’pose the house hunt thing isn’t a bad idea.’

‘No, but I don’t see too many For Sale signs,’ Mumtaz said.

They walked up Carter Lane and came out opposite the cathedral. All signs of police activity seemed to have disappeared.

‘So who you gonna be then?’ Lee asked her as they crossed the road and walked into the churchyard. ‘The Avon lady?’

‘No, I—’

‘Wilko!’

Suddenly he’d unhooked his arm from hers and Lee was running.

‘People lie,’ Habib said.

‘Yeah, but …’

‘Loz, you’ve got to listen!’

The two boys were up in the Arnold Circus bandstand, at the top of Brick Lane, eating rainbow bagels stuffed with salt beef, mustard and pickles.

‘If Kym really is pregnant and she really does need money for an abortion then she’d ask you for that first, not a phone,’ Habib said. ‘And anyway, she doesn’t need money for an abortion. We have the NHS!’

‘She wants to go to some clinic,’ Loz said miserably.

‘So she can bloody do one, then, can’t she!’ Habib shook his head. ‘Loz, I know you said you … with Kym, but …’

‘I shagged her!’ Loz said. ‘Alright?’

While not being the boy least likely to induce a teenage pregnancy at their school, Loz also wasn’t the most obvious candidate. He wanted to have sex – they all did – and he’d boasted about it when he’d supposedly done it. But he hadn’t mentioned Kym. Not like some of the other lads they knew, who would go on to call their conquests ‘slags’ and ‘hoes’.

‘OK! OK!’ Habib waved his bagel at his friend. ‘But look, you’ve seen her dad. If you were a girl and you got pregnant, wouldn’t you be more afraid of him finding out than anything?’

‘He calls her his princess,’ Loz said.

‘Yes, but she won’t stay one with a baby on the way, will she?’

‘Dunno …’ Loz chewed, then he said, ‘But if she tells him, I’ll get in trouble with the law.’

‘No. No!’ Loz was his best mate but he could be thick as mince sometimes. And this wasn’t the first time Habib had told him. ‘No, she’ll get in trouble because you’re fifteen and she’s sixteen.’

‘Yeah, but it was me what …’

‘Doesn’t matter!’ Habib said. ‘Listen, you know my cousin Nazrin, you know she’s a lawyer, right? She says sixteen is when you’re allowed to have sex. You’re fifteen—’

‘So I done wrong!’

‘Yes, you did but … Look,’ Habib said, ‘it was wrong, but you’re not in the wrong, do you understand? Kym’s in the wrong because when you had sex, she was sixteen and so …’

‘Oh …’