9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Hakim & Arnold

- Sprache: Englisch

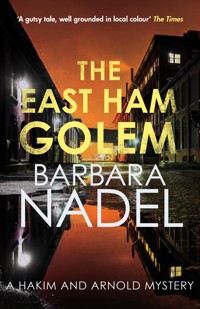

'This series has brilliantly established itself and this latest is another masterpiece from Barbara Nadel'CRIMESQUAD A friend from the past asks for private investigator Lee Arnold's help in tracing his son: Fayyad al'Barri was last thought to be in Syria having embraced radical Islam. But a cryptic message has prompted his family to believe Fayyad has had a change of heart and is searching for a way back home. With fellow investigator Mumtaz Hakim's help, they might be able to establish contact. From the bright lights of the Western world, to shady boxing clubs and murky online jihadist recruitment, and while violence erupts close to home, Mumtaz and Lee are on an unknown path into the mind of a terrorist, journeying closer to danger than they ever imagined.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 416

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

BRIGHT SHINY THINGS

BARBARA NADEL

To Senan, with love

Contents

PROLOGUE

As the body hit the floor, some of the dead man’s blood caught the side of her face and she gasped. It was still warm.

She made herself look down. Drawn to the source of the blood, she fixated on his torso, which was a mass of red punctuated by deep, black stab wounds. Then she looked at the face. Which she recognised.

ONE

‘He shit his pants! I’m telling you, I was there!’

Abbas al’Barri was drunk. He’d been drunk in 1991 when they’d first met. Twenty-six years later, he was drunk again.

‘I’ll admit he pissed himself,’ Lee Arnold said.

‘And shit! I’m telling you, man! He shit his pants! I saw it and I smelt it!’

Lee shrugged. There was no point arguing with Abbas when he was rat-arsed. The bottle of whisky he’d opened when Lee had arrived was half empty. And Lee didn’t drink.

‘Fucking “elite” Republican Guard!’ Abbas said. ‘Fucking Ba’athist scum!’

Although it still, sometimes, haunted his dreams, the First Iraq War was over for Lee Arnold. Since he’d left the army, shortly after the War in 1992, he’d first joined the Metropolitan Police force and then set up in business as a private investigator. The bloody battles against Saddam Hussein’s Republican Guard were not memories he liked to invoke. But he hadn’t come to this smoke-filled house in East Ham for his own amusement. Abbas was laughing but that was only because he was shit-faced. And he was shit-faced because he was still there in his mind. All the time.

On the night of 26th February 1991, Lee had been driving a Challenger 1 tank into battle against the 52nd Iraqi Armoured Division. As a corporal in the 7th Brigade of the British 1st Armoured Division he’d been part of the multinational force that had been sent to recapture Kuwait from Iraqi occupation. He’d been sweaty with fear, hoarse from smoking too many fags and he’d also had a passenger on board. One of the Brigade’s Iraqi interpreters, Abbas al’Barri was a Shia dissident from the northern Plain of Ninevah. He’d been arse’oled before he’d even got on board.

The first thing he’d ever said to Lee had been, ‘I’m a very bad Muslim. But what in the name of God are you to do?’

They’d hit it off straight away and when what became known as the Battle of Norfolk was over, they’d gone out drinking together in the southern Iraqi city of Basra. There, for the first time, they’d discussed how many Republican Guards had pissed or shit themselves, or both. Back then, a good night out for Lee Arnold had meant a bottle of vodka and a ‘ruck’.

Abbas had been handy in a fight all those years ago too. But, although the drink was still in his life, the fight had gone. That had disappeared the day he’d discovered that his eldest son, Fayyad, hadn’t gone to Ibiza for a booze and birds holiday with his mates, but had joined the Islamic State Group in Syria. Lee remembered that day well because it had been the first time that Abbas had called him for years.

When Lee had returned to the UK in 1992, Abbas and his family had also left Iraq. Like most of those who had translated for the foreign coalition, the al’Barri family would have been at risk from Saddam Hussein had they tried to stay. So Abbas, his wife Shereen and their children Fayyad, Djamila and Layla had been settled in a council house in East Ham. Two years later the al’Barris’ youngest child, Hasan, had been born in Newham General Hospital. Lee and Abbas had ‘wet the baby’s head’ for two days of happy drunkenness. The next time they’d seen each other, Abbas’s name had been all over the newspapers as the father of the latest ISIS recruit. And his drunkenness was dark.

Now, it was even darker.

Hasan and Lee put Abbas to bed when he finally became unconscious. The boy, unlike his mother, was embarrassed. Shereen was furious. Later, sitting down in her kitchen with Lee and a jug of strong coffee, she told him why Abbas had really wanted to see him.

‘We got this in the post on Monday,’ she said as she pushed a large Jiffy bag across the table.

Addressed to Abbas, the postage stamp was Dutch.

Lee opened the bag and frowned. ‘Ivory?’

‘No,’ Shereen said. ‘It’s the tooth of a whale.’

Lee removed it. About ten inches long, it looked like a massive incisor from a chain-smoker. The surface of the tooth was rough and, when Lee held it to his nose, it smelt of damp.

‘So …’

‘Lee, may I have one of your cigarettes, please?’ Shereen asked.

He didn’t think she smoked any more. But he said, ‘Course you can, darlin’.’

He offered her a fag and took one for himself. Once her smoke was alight, Shereen said, ‘You know that we come from Ninevah. Do you remember?’

‘Yes,’ he said. ‘The Ninevah Plain used to be full of all sorts of people before ISIS. Shias, Christians, Yazidi people …’

‘That’s right. Many, many mosques, churches, monasteries – holy places of all kinds. Even under Saddam. The monks even taught our children. But that was then,’ she said. ‘Now these monsters my son has chosen to join …’ She threw her arms in the air. ‘Since when were we Sunni? Tell me, Lee, since what time did my son become someone else?’

‘I don’t know.’

Her eyes filled with tears. ‘What did I do, eh? We always kept the children away from religion. We saw this madness coming. What did I do for … this?’

He said nothing. The poor woman was confused and who could blame her? Her son had chosen to go to a lawless country to fight for a cause she couldn’t understand.

Shereen shook her head. ‘But … Look,’ she said, ‘we’ve not had a word from Fayyad since last August. Not one text, not one phone call. Then …’ She pointed at the Jiffy bag. ‘This.’

‘It’s his handwriting?’

‘Yes. But more significant is the content,’ she said.

‘A whale’s tooth?’

‘Yes. But not any whale’s tooth,’ she said. ‘This is the tooth from the whale that ate the Prophet Jonah.’

‘In July 2014, ISIS blew up the Mosque of the Prophet Yunus, which is our name for Jonah,’ Shereen said. ‘It contained the tomb of the prophet as well as a relic, which was a copy of the Tooth of the Whale.’

‘A copy?’

‘Yes. Given to the shrine by American soldiers in 2008. We were so embarrassed.’

‘Why?’

Shereen had switched off the harsh neon lighting strip in the kitchen in favour of candles, which gave off a softer light. She was beginning to get cataracts and candlelight was more comfortable for her eyes. But Lee noticed that it also made her look older. The light and shade the candles threw picked out every hard-won line and crinkle on her beautiful face.

‘The Americans believed the story we told about the tooth being stolen,’ she said. ‘It was a story that the people of the Ninevah Plain created to protect our relic. Even then there were people coming onto the Plain who meant us harm. Al-Qaeda, Salafis, madmen. The imam of the Mosque of Jonah gave the tooth to the monks of the Monastery of Mor Isak. High up in the mountains behind the Christian town of Bartella, it is a hard place to get to. And it is big. Now there is only one monk, but in the past there were thousands. Brother Gibrail put this tooth into the wall of the monastery. He told no one the exact location, not even Brother Serafim, his only companion at that time. That way if anyone came and asked where was the tooth, no one but Brother Gibrail would know and he would kill himself before he would give that secret to the madmen. In December of last year he did just that.’

‘He took his own life?’

‘Yes.’

Now the low light was eerie. Shereen was calling back the memory of Iraq far more powerfully than her husband. She spoke of a place Lee remembered as a pressure cooker of the fanatical. One day he saw a huge group of men, Shias someone had told him they were, beat themselves with chains until they fainted from blood loss. It was an act of devotion apparently. But to what?

‘ISIS came and they blew up Mor Isak,’ she said. ‘Brother Serafim escaped. He said that they left not one stick of furniture intact, not one plant in the garden alive. There is a woman who lives in Dagenham that I know, Nasra. She is a Syrian Christian from Ninevah. She told me that everyone was saying that the tooth was lost. And I believed it to be so, until this arrived.’

Lee held the artefact up to the light. ‘You’re sure this is the real deal?’

‘Lee, I grew up looking at that tooth,’ she said. ‘And so did my two eldest children. The tooth was very precious to both Fayyad and Djamila. One of their favourite things as little ones was to go to see the tooth when it was in the Mosque of Yunus. When we heard it was moved to Mor Isak, my Fayyad cried.’ She touched the rough surface of the dark-brown object lovingly. ‘Abbas and I believe that our son has had a change of heart.’

‘About ISIS?’

‘Why else would he preserve something those madmen find abominable?’ She leant towards him. ‘Lee, Fayyad is reaching out to us. He wants our help.’

‘To do what?’

‘To come back to us!’ she said. ‘The Tooth of the Whale tells me this more powerfully than any letter.’

‘Maybe he just sent it home for old time’s sake,’ Lee said. ‘Shereen, love, I don’t mean to rain on your parade, but this needn’t mean anything. Worse, it could be a trap.’

‘A trap?’

‘To give you false hope. You know how twisted these bastards are! They encourage these young blokes to reject their families, to actively torment them in some cases. You’re “infidels” now, why should he care about you?’

Shereen looked down at her hands.

‘I can see it’s crossed your mind,’ he said.

‘But not Abbas’s.’

‘Well, no.’

‘Lee, if Fayyad doesn’t come home, Abbas will drink himself to death,’ she said. ‘He can’t take it. He just can’t.’

‘Have you told the coppers?’ Lee asked.

He saw the candlelight flicker in her slightly milky eyes. It gave them a vaguely sinister, unearthly look.

‘Oh, no,’ she said. ‘Abbas is adamant. No coppers. He wants you to find Fayyad.’

‘I said I’d finish my A levels and I will.’

The gangly girl sprawled across the sofa didn’t take her eyes from the TV as she spoke. Shazia Hakim was, to the annoyance of her stepmother, addicted to dark, Scandinavian crime dramas. Wasn’t there enough gloom in everyday life? She was also, in Mumtaz Hakim’s opinion, being dangerously casual about her own future.

‘If you go in under the graduate entry scheme …’

‘I don’t want to wait that long,’ Shazia said. ‘I’ve already taken an extra year for my A levels. And, anyway, I want to go in as an ordinary constable. I want to learn from the bottom.’

‘Shazia, you know that, at that level, you may face …’

‘Racism and sexism. Yeah, I know, Amma.’ She shook her head. ‘You’ve talked about it, Lee’s talked about it, Vi’s talked about it. And as I’ve said to all of you, if Asian girls don’t go in and change it, then who will? Anyway, if I join up when I’ve finished my A levels I can start earning and you won’t have to worry about nine grand a year uni fees.’

Mumtaz put the book she’d been trying to read down. Science fiction had never really been her thing but she was giving it a go because her cousin Aftab had recommended it.

‘Shazia,’ she said. ‘As I’ve become tired of telling you, don’t think about money. I have that covered.’

The girl looked, briefly, away from the TV. ‘No you don’t.’

Mumtaz ignored her. ‘What about your application to Manchester University? What happened to that?’

‘You know what happened.’

Shazia turned back to the TV and Mumtaz said no more.

The subject of the Sheikh family and what they had done to Mumtaz and Shazia was a closed book. Shazia’s late father had been in debt to the Sheikhs, a local crime family, when he’d been stabbed to death on Wanstead Flats nearly four years earlier. A gambler, a drunk and a womaniser, he’d habitually raped both his first wife and Mumtaz. He’d also abused his own daughter. Shazia hadn’t cried when her father died. She still didn’t know that Naz the spoilt favourite nephew of the Sheikh family patriarch, Wahid-ji, had been the one who had killed him. And now that Naz himself was dead, theoretically that information had died with him. Except that Mumtaz knew it hadn’t. Because she’d been there when Naz had killed her husband. She’d let him get away as Ahmet had lay dying. She’d let him die. Then the Sheikhs had begun blackmailing her.

The two Hakim women had secrets from each other that neither of them barely dared to even think about. Shazia carried guilt, Mumtaz did too, but there was also fear because the Sheikh family hadn’t finished with the Hakims. Only one person apart from Mumtaz knew about the Sheikhs and that was her business partner, Lee Arnold. And even he didn’t know the whole story.

Fayyad was not the skinny boy that Lee remembered. Now a tall, muscular man in his thirties, he had a beard and carried a semi-automatic rifle. In this picture he was smiling. Lee pointed at the computer screen. ‘How’d you find this?’ he said.

‘They have websites dedicated to getting brides for their fighters,’ Shereen said.

‘But this is Facebook.’

‘Read it,’ Shereen said. ‘He says he’s looking for a wife.’

Lee had heard that one of ISIS’s most powerful recruiting tools amongst Muslim women was its stable of young, fit, handsome fighters. Pictures were put online to draw in those already in the early stages of radicalisation. A handsome face and a set of muscles like Fayyad’s could clinch it. Lee barely recognised him. He called himself Abu Imad. All the fighters had new names signalling their ‘rebirth’ as adherents of ISIS.

‘When did you find this?’

‘We’ve been looking online ever since he left,’ Shereen said. ‘Djamila found this a few days after we got the tooth.’ She touched his arm, desperate for him to believe. ‘You see he’s reaching out online and by post.’

‘Yeah, reaching out to entice some vulnerable girl to go and join him in Raqqa,’ Lee said.

‘No! No! Lee, you don’t understand!’

‘I think I do,’ he said. ‘Shereen, love, I know you want to think—’

‘He sent the tooth from Amsterdam,’ Shereen interrupted. ‘ISIS people use Amsterdam as a transit point to go on to Istanbul and then into the Middle East. They come into Europe via Schiphol Airport and they leave from there too.’

‘How do you know this?’

‘Because I have read everything there is to read about these bastards!’ She began to cry.

Lee let her and then he said, ‘Whatever’s going on here, you have to tell the police. I can’t help you. I’m not an expert on terrorism. I’m not an expert on much.’

‘But you work with a covered lady,’ Shereen said.

Lee frowned. ‘How’s that relevant?’ he said.

TWO

Mrs Butt’s husband, Nabeel, was indeed having an affair with Mrs Kundi who ran the Fatima Convenience Store in Manor Park, just as Mrs Butt had suspected. Mumtaz had photographs of twenty-five-year-old Nabeel locked in a passionate embrace with the sixty-year-old widow who was, it had to be said, extremely well preserved for her age. She was also loaded. As well as the convenience store on the Romford Road, her late husband, Sadiq, had left her one massive house in Forest Gate plus a string of flats all over the East End, which were rented out. Mrs Butt, a pretty twenty-three-year-old with two small children, shook her head.

‘He has had more money lately,’ she said. ‘Must’ve got it from her. Silly old bag! He’s been buying the kids computer games they’re too young to use. Course he plays them himself.’

Nabeel Butt was a very handsome young man whose main fault, apart from unfaithfulness, was his complete refusal to work. That was down to his wife who toiled most of the day and part of the night in her father’s launderette in Plaistow. Her mother looked after her twin girls while Nabeel pleased himself and, apparently, Mrs Kundi too.

‘What will you do?’ Mumtaz asked. It had to be hard to see a photograph of your husband being pleasured by a much older woman half hidden behind a stack of Coca-Cola bottles. Getting that shot hadn’t been easy. Standing in the rain for hours, waiting for the convenience store to close.

‘I dunno,’ the young woman said. ‘I’ll have to think about it. Me dad’ll go bonkers once he knows. But then he might blame me. You know how it is.’

They shared a look. Oh, Mumtaz knew how that was. Girls who wanted to divorce errant husbands were often accused of not being ‘good’ wives, which either meant they needed to work harder, have more children or allow their husbands sexual favours they found distasteful. Not that her own father had behaved like that. Baharat Huq had been as glamoured as everyone else by the lies handsome and apparently successful businessman Ahmet Hakim had told so that he could marry Mumtaz. But after Ahmet’s death, when she’d finally managed to tell her father about the beatings and the rapes she had endured, he had been mortified. He had blamed himself.

‘I can’t advise you,’ Mumtaz said. ‘It’s not what private investigators do.’

When Mrs Butt left the office, Mumtaz had her lunch at her desk. Lee was out with a prospective client who had looked as if he’d had a very rough night. They’d gone to the Boleyn pub at the other end of Green Street which, given the client’s state, hadn’t seemed like the best idea. But what did she know? The client was, apparently, one of Lee’s old friends from the First Iraq War. An Arab, by the sound of his name.

‘Shereen told me everything,’ Lee said.

‘She said. You think we should go to the police,’ Abbas al’Barri said.

‘I know you should,’ Lee said. ‘You should also stop drinking too. You look like shit, mate.’

Abbas looked at the double whisky in front of him.

‘Hair of the dog.’

There weren’t usually many people in the Boleyn. There never had been that many on weekday lunchtimes in recent years. But at least up until the previous football season, the pub had done well on match days. Now West Ham United had moved to the Olympic Stadium in Stratford even that trade had disappeared. And when the property developers who’d bought the old Boleyn ground started to demolish it and build posh flats, the pub was probably for the knacker’s yard.

Lee said, ‘I know he’s your son, but Fayyad openly admits he takes part in ISIS activities in Syria. He’s a terrorist.’

‘He’s trying not to be!’ Abbas said.

An elderly man looked up from behind his copy of The Sun, sniffed and then walked out to have a fag on Green Street.

‘You don’t know that.’

‘And you don’t know that he isn’t reaching out!’

‘No. I don’t. But what I do know is that those counterterrorism officers who worked with you when Fayyad took off for Syria are the best people to help you.’

‘This looking for a wife thing is nonsense!’ Abbas said. ‘He never wanted to be married!’

‘How do you know?’

‘He never discussed it with me.’

Lee sipped his Diet Pepsi. It was probably rotting the hell out of his guts but it was better than the booze and painkillers he’d slung down his neck for more years than he cared to recall. At least Pepsi didn’t make him behave like a twat. Like Abbas.

‘Shereen told me you’ve got some idea about contacting him on Facebook.’

‘Yes! You—’

‘I can’t do it,’ Lee said. ‘Outfits like ISIS monitor social media. Assuming for a moment that Fayyad does want to come home, then I might inadvertently say something to him that would get him into trouble. They could kill him.’

Abbas looked into his whisky glass.

‘You had a family liaison officer, didn’t you?’

‘A Sikh woman.’

‘Then contact her,’ Lee said.

He shook his head. ‘She just made tea and said comforting words. She was about twenty at the most,’ he said. ‘What can such a person know? And we can’t contact him, Shereen or me. We can’t bear it. What if we’re wrong? What if this is some sort of cruel joke? Lee, I know you work with that Muslim lady …’

‘Mumtaz isn’t getting involved,’ Lee said. ‘I won’t have it.’

‘She works for you. She must do what you tell her.’

‘Not if what I ask her is bad for her,’ Lee said. ‘And this would be. Believe me, Mumtaz’s got enough shit in her life without getting inside the head of someone who’s been fighting in Syria. It’s fucking dangerous. You should know that.’

Abbas didn’t answer.

‘Go to the police and tell them,’ Lee said. ‘There’s nothing me or Mumtaz can do for you.’ Then he stood up. ‘I’m going out for a fag,’ he said.

As he passed him, Lee heard Abbas say, ‘You owe me.’

She was right, the old man was looking at her.

‘You think that old bookie want to give you some lovin’?’ Grace said to Shazia.

The girls were sitting on the wall outside Newham Sixth Form College. Shazia was eating a KitKat while Grace smoked a fag. Grace’s mum and dad belonged to what she called the ‘happy clappy’ church next door to Tesco’s on the Barking Road. They didn’t approve of smoking. Which was why Grace had to do it.

‘You know him?’ Grace asked. ‘He, like, an uncle or something?’

‘No.’

He wasn’t and Shazia didn’t know him, as such. But she had seen him, often. And whenever that happened he always seemed to be staring at her. Was it just paranoia? A lot of girls dreaded being spotted by a single or widowed, much older man. Being taken a fancy to by an old guy with money sometimes meant that an offer of marriage would be received. The only consolation for Shazia was that her stepmother would never agree to such a match. Shazia knew that to the bottom of her soul. What she also unfortunately knew was that her amma was also skint, beggared by those bastards her dad had been in debt to. The old man walked away.

‘So you comin’ down the chicken shop after college?’ Grace asked.

Grace had the hots for a local bad boy who called himself ‘Mamba’. Like Grace, he came from a God-fearing and intensely moral Nigerian family. No one knew what Mamba – whose real name was Benjamin – was like at home, but on the street he was all ‘gangsta’. Grace was besotted.

Shazia shook her head. ‘Nah.’

‘Oh, girl, why not?’

‘Got work to do,’ she said. ‘If I don’t do it, mum’ll give me shit.’

‘She just your stepmum,’ Grace said dismissively.

‘Yeah, but if I’m ever going to get out of Newham, I have to get my exams.’

‘To go uni, yeah.’

She hadn’t told Grace, or anyone apart from her amma, that she was actually going to join the police. If she was. She’d started to rethink her plans in the past few days. Maybe going to university and then joining the police was the way forward? If nothing else it would put off the evil moment when she had to tell her friends that she was going to become a ‘fed’.

‘There other ways to get out this shithole,’ Grace said.

‘Yeah.’

Grace caught the downbeat tone in Shazia’s voice. ‘I don’t mean becoming some gangsta’s baby mama. I ain’t doin’ that.’

‘Unless Mamba asked you.’

Laughing, Grace pushed her, ‘Cheeky bitch!’

‘Just sayin’,’ Shazia said.

The girls chatted on until it was time for their afternoon sessions to begin. But when, later, Shazia came out onto the street to go home, she saw that the old man she’d seen earlier had reappeared. Once again, he stared at her. Who was he and what did he want?

DI Violet Collins might be the rough side of fifty and as curvaceous as a stick, but she knew how to give a bloke a hard-on. Lee put his hands on her waist to guide her as she rose and fell on his erection. When they’d finished and were laying on his bed smoking post-sex fags she said, ‘That’s set me up for a few weeks. Ta, darling.’

He smiled. Then noticing that her cigarette had a long and precarious piece of ash on the end he said, ‘Don’t get it on …’

‘The duvet. I know,’ Vi said as she flicked it off into an ashtray on the bedside cabinet. ‘I know you, remember? Like no one else.’

She did. As well as being occasional lovers, ‘fuck buddies’ as Vi liked to put it, they’d worked together for ten years when Lee had been in the Met. Also, long ago, she’d saved him from himself. The First Gulf War had left Lee Arnold a wreck. Addicted to booze and painkillers, he’d been on the road to self-destruction until Vi had turned up one day with a cage containing a mynah bird. As she’d handed it over to him, she’d said, ‘You might want to kill yourself, but this poor innocent sod doesn’t deserve to die. Look after him.’

The bird, who Lee named Chronus, hadn’t been the prettiest pet on the block but he was bright and had very quickly learnt all of Lee’s favourite West Ham United songs and team lists. He also, just by his presence, made Lee clean up his act. Although the fags remained, the booze and the drugs went. But at a price. Lee Arnold spent at least four hours every day cleaning his small flat in Forest Gate. Nightmares about Saddam Hussein’s Republican Guard had been replaced as the enemy by dust.

But although, as ever, mindful that Vi could be sloppy with her fags, Lee wasn’t thinking about dust as he lay next to her, naked, staring at the ceiling. His mind was still on Abbas al’Barri. Absolutely convinced that his son was reaching out from the heart of ISIS-controlled Syrian territories, Abbas was a man in torment. What he wanted, which was for Fayyad to come home in one piece, was almost impossible. Occasionally someone managed to escape, but those people were always under suspicion, which Lee could understand. However horrific the methods used by ISIS were, recruits to their cause had still gone to them knowing, and approving, of their philosophy. Runaways were watched by the security services, probably, in many cases, with good cause.

Like Abbas, however, Lee was intrigued by the Tooth of Jonah’s Whale. It was the sort of thing the ISIS boys would automatically destroy. Anything that could be considered even remotely idolatrous was either smashed up or, if it was worth something, flogged to some greedy collector online. Had Fayyad sent the tooth to his parents for old times’ sake? If he had, he wasn’t a very good ISIS member. And what, if anything, did his appearance on Facebook so quickly after sending the tooth home mean? If anything? Was he ‘reaching out’ or was he simply trying to reel in young female recruits using his good looks and big muscles as bait? And why was Lee even thinking about it, anyway? He’d told Abbas he couldn’t and wouldn’t help him and he’d advised him to go to the police. He looked at Vi who appeared to be sleeping. Should he tell her?

Lee knew why he was thinking about Abbas and that was because, as Abbas himself had pointed out, he owed him. The Iraqi translator had taken a bullet in the leg for his British soldier friend and Lee knew that, even now, the nerve damage it had caused troubled him. It wasn’t the only reason that Abbas drank, that had all started when he’d got himself banged up in one of Saddam’s prisons in the 1980s, but that catastrophic leg wound hadn’t helped.

‘You’re very quiet, Arnold,’ Vi said. ‘Penny for ’em.’

She always knew when he was worried about something. She usually knew when he was keeping something from her. Even her own DS, Tony Bracci, called her a fortune teller. It’s what her Gypsy mum had been.

Lee knew he should tell her about Abbas. Protocols existed to deal with these situations, protocols that were there for a reason. But he was hesitating and he knew he was doing that for a reason. Coppers, even the exalted graduate types who tended to drift towards sexy jobs like homicide and counterterrorism, sometimes got it wrong. Sometimes people who weren’t villains got banged up, sometimes people, whether innocent or guilty, died. None of it was, usually, deliberate. The coppers were under pressure for results and shit happened. But shit couldn’t happen to Fayyad al’Barri. When the family had finally managed to get out of Iraq in ’92, Lee had gone to Heathrow to meet them. He still remembered the sight of Fayyad solemnly carrying his one precious possession, which had been a Frisbee. It was all the ten-year-old had left. Djamila, his eight-year-old sister, had run into ‘uncle’ Lee’s arms but Fayyad had held himself aloof. He’d already been too damaged by war to risk outward shows of affection. But over the years Fayyad had learnt to smile again and, when he’d left to join ISIS, it had come as a shock to everyone, including Lee. Fayyad couldn’t be put at risk, he was too precious.

And Lee Arnold owed his father. He looked at Vi and said, ‘I’m alright.’

It was nearly midnight when the front doorbell rang. Shazia was asleep. Mumtaz felt a tiny jolt of fear. The old man had agreed to wait until Shazia had finished her A levels before coming to formally make his disgusting proposal. That was still three months away.

She spoke into the intercom. ‘Who is it?’

‘Lee.’

She let out a shaky breath and buzzed him in.

Mumtaz made ‘English’ tea with milk, which they drank in her darkened garden so that Lee could smoke. He told her everything about Abbas al’Barri, his family and his son Fayyad.

‘Seems it’s normal for these ISIS fighters to go online and use their well-developed pecs as bait,’ he said.

‘I’ve heard of such things, yes,’ Mumtaz said. ‘I know several ladies who are worried about their daughters. Not clients, just people I see around. The Internet, useful though it is, has some lethal downsides.’

Lee looked at his glowing fag end. ‘Shopping,’ he said.

‘Shopping?’

‘Being a bit glib, I s’pose, but Jodie’s racked up over a grand’s worth of debt online shopping,’ he said. ‘So her mother tells me.’

Lee’s daughter Jodie lived with his ex-wife in Hastings. To Lee’s horror the nineteen-year-old was, like her mother, interested in little beyond shopping, tanning and celebrities.

‘You’re not going to pay it off, I hope,’ Mumtaz said.

‘Couldn’t even if I wanted to.’ He smoked. Then he said, ‘If I pose as some little Muslim girl already in love with the idea of sodding off to the caliphate and marrying a fighter …’

‘You’ll never get away with it,’ Mumtaz said. ‘On Facebook you might just get away with it. But, from what I’ve heard, these men want to see what they’re buying before they buy it.’

‘Buy?’

‘It’s a figure of speech,’ she said. ‘They want to know what these prospective brides look like. They want to be sure they’re not too old or scarred, fat or have, I don’t know, big noses or something. They want young, pretty women they can breed with. So they use Skype.’

‘Fayyad is on Facebook.’

‘Yes and if a girl with a pretty photo on her page contacts him then he’ll want to Skype her,’ she said. ‘And even if you cover and say you’re way too religious to show your face on Skype, your voice and your size will give you away.’

‘So I have to find a girl …’

‘A woman,’ Mumtaz said. ‘Girls are way too vulnerable. Spending time inside the head of a man who, even if he is now a reluctant terrorist, may have killed people, is not something with which a girl could cope. The police have people who will be able to do this sort of thing.’

‘I know,’ he said. ‘But Abbas doesn’t trust them. And he’s sick, in his head. I’ve never seen him so bad. He thinks they’ll do so many checks to make sure they’re not being duped that they’ll lose him. And that may happen.’

‘And it may not,’ she said. She paused. ‘But I know that in your awkward, round the bushes British way, you’re asking me if I’ll help you and I will.’

‘No.’

‘Yes. I know you owe Abbas your life and I owe you.’

‘You owe me nothing,’ he said. ‘I haven’t done anything. Not yet.’

‘But you will,’ Mumtaz said. ‘You will speak to my brother Ali and persuade him to change his ways and I know you’re gathering intelligence on the Sheikhs.’

‘I—’

‘I’ve seen your files!’ she said. ‘Don’t try to tell me you’re doing nothing!’

He didn’t. He just sat.

Having beggared her for her husband’s gambling debts, the local crime family, the Sheikhs, were now coming for Shazia. Although the girl hadn’t killed him, Shazia had been with the family’s favourite son when he’d been stabbed. She hadn’t known that it was Naz who had killed her father, but she had been aware that he had been taking money from Mumtaz. And so in spite of the fact that Naz had been killed by a Pole employed by a rival Asian gang, because Shazia had been at the scene, Sheikh family honour had to be satisfied. This was to be done by Mumtaz giving Shazia in marriage to the current head of the Sheikh family, seventy-year-old Wahid. If she failed to deliver the girl when she finished her A levels the Sheikhs would inform the police on Mumtaz’s brother, Ali, who was giving shelter to radicalised young men in his house on Brick Lane. Lee had offered to help. But what he didn’t know was that Mumtaz and Shazia had more in common than he thought. Even Shazia didn’t know that her precious stepmother had watched her father bleed to death when Naz Sheikh had stabbed him. In that moment, she’d had enough. The Sheikhs had never let her forget that or the idea that they could tell Shazia her secret any time they wanted.

‘I don’t want you to do this,’ Lee said as he lit another cigarette. ‘You’ve enough on.’

She ignored him. ‘So this Abbas and his wife,’ she said. ‘What do they do? Do they work?’

‘Abbas works for the BBC Arabic service, Shereen teaches maths.’

Mumtaz leant back into her chair and looked into the candle flame on the patio table.

‘I saw when ISIS blew up the Mosque of Jonah on the news,’ she said. ‘Whatever one may feel about relics they have value for a lot of people. Whether they are genuine or not is almost immaterial. People make an emotional investment in such things and it is that which makes them meaningful.’

‘With your psychology grad’s head on,’ Lee said. ‘What about as a Muslim? How’d you feel about the Tooth of Jonah’s Whale with that hat on?’

She shrugged. ‘The al’Barris are Shia, I am Sunni. We are more austere in our relationship to buildings, tombs, relics. But some amazingly ornate monuments are Sunni and we do revere the inanimate. What is the Holy Kaab’a in Mecca if not an object of veneration? Ordinary Sunni people have no problem with any of this. Difficulties arise with people like ISIS who have this notion that any form of man-made structure, any artefact that is revered is an abomination. Their caliphate, as I perceive it, should it come into being, will be a twelfth-century environment with selective modern graft-ons like mobile phones, modern weapons and the Internet. Without those things they couldn’t survive, which is, of course, one of their great weaknesses.’

‘So what are their strengths?’ Lee asked.

She thought for a moment and then she said, ‘Their ability to get inside people’s heads. The message ISIS sends is uncompromising and takes no prisoners. It is sure, it is certain and there is great comfort in it.’

‘Comfort?’

‘Yes,’ she said. ‘Any kind of certainty is comforting. What ISIS offers is right and wrong, heaven and hell with no ambiguity. Break the rules and you will die both here on earth and in heaven. But do everything we tell you and we guarantee you will have dominion over all others and you’ll go to heaven too. What’s not to like?’

THREE

‘Rajiv-ji!’

For a moment the tall, leather-clad man kept on walking. As one of the few Hindu traders on Brick Lane as well as being the only openly gay man, Rajiv Banergee was deaf to any sort of approach on the street. And even though the caller had addressed him politely, Rajiv spat back a venomous ‘fuck off!’ just in case. But when he did turn around he saw a friendly face and he blushed.

‘Oh, Baharat-ji!’ he said. ‘I do apologise for my language! I am so, so sorry.’

The old man, Baharat Huq, smiled. ‘You get a lot of unwanted attention, Rajiv-ji,’ he said. ‘I would do exactly the same myself if I had to put up with these terrible boys round here.’

‘Them?’ he laughed. ‘They’re a joke, Baharat-ji. I don’t worry about them.’

He looked at a small group of teenage boys wearing shalwar khameez and kufis. Some of them he recognised as members of a street gang known as the Briks Boyz. All of Pakistani and Bangladeshi heritage, they fancied themselves as guardians of Muslim pride in the Spitalfields area. In reality they were at best anodyne, at worst, thuggish.

‘Rajiv-ji, I wanted to speak to you,’ Baharat said.

‘Oh.’ He frowned. ‘Nothing bad, I hope.’

The old man smiled. ‘Don’t worry,’ he said.

Rajiv brightened. ‘Oh well, come to the shop,’ he said. ‘I’ll get my boys to make tea.’

Rajiv had inherited the Leather Bungalow from his father when the old man had died back in the 1980s. Back then Rajiv had cross-dressed with pride, but now although still as slim as a whip, he contented himself with a little eyeliner, some mascara and an assortment of large, very dressy rings. The world had changed and, to Rajiv’s way of thinking, for the worse.

Sitting in the dingy little office at the back of the leather shop, the two men made idle gossip until one of Rajiv’s assistants brought them tea. Once the boy had gone the old man said, ‘Rajiv-ji, I understand from my friend, Mr Berman …’

‘Ah, Lionel, yes.’

‘I understand from him that yesterday you were abused in this your own shop by a boy who is currently staying with my son, Ali.’

‘One of the Arab boys?’

‘Yes.’

Rajiv laughed. ‘Oh, yes. He put his head around the door and shouted “Faggot”. Then he ran away. It was pathetic. Actually it would have been funny if Lionel hadn’t been so upset about it.’

‘Yes, well I too am upset about it,’ Baharat said. ‘And I wish to apologise. Ali will not, as you know. I have told and told that boy that what he is doing with these riff-raff he takes in is not in any way advancing the cause of Islam, but he takes no notice. I tell him, real Muslims do not persecute any creature, human or animal. But he continues with this, excuse me, shit, about my being taken in by “Zionist lies”. One day the police will come for him. I know it! How can a man have two such wonderful children in Asif and Mumtaz and then such a ridiculous boy like Ali?’

Rajiv shrugged. He didn’t have any children, what did he know? But he did like Baharat’s daughter, Mumtaz. In an attempt to change the subject, he asked after her.

‘Still working as a detective,’ the old man answered proudly. ‘And her stepdaughter is doing very well with her A levels. She will go to university. I tell you, Rajiv-ji, it is a good job that girl has my daughter as her mother. That waste of space, her father, put the child into a private school and forgot about her. Mumtaz takes an interest. But then, she is a clever girl.’

‘She always was, Baharat-ji.’

‘Indeed. Worth ten, no, a hundred of that vile trickster I gave her to.’ He shook his head. ‘There are days, you know, Rajiv-ji, I find it hard to live with myself. My Mumtaz has endured such hardships because of that man! And you know, sin though it is, I am happy that Ahmet Hakim is dead. May God forgive me.’

Uncomfortable with ‘God talk’ Rajiv again changed the subject. ‘Well you tell Mumtaz and Shazia to come in when they visit you next time,’ he said. ‘If the little one is going to university she will need a nice stylish jacket. I see all the smart girls wearing leather bombers these days. And no charge, Baharat-ji.’

‘Ah, but—’

‘No, it will be my pleasure,’ Rajiv said. ‘Truly. Only cost will be a chat with the lovely Mumtaz.’

It was only when Baharat looked closely that he saw the shadow of a bruise on Rajiv’s right cheek, underneath his foundation.

He wasn’t her type. Mumtaz had never been attracted to musclemen and Fayyad al’Barri was clearly muscle-bound. She preferred thin, aquiline men, like her late husband, like Lee Arnold. Also, Fayyad had a wispy beard that he’d dyed red. A lot of the ultra-religious men did that. But in spite of that, she could see why people would find him handsome. He had full lips, almost like a girl’s and the most soulful, large green eyes. Predictably his profile was an exercise in bragging. He was a ‘warrior’, a ‘sword of God’ and ‘fearless’. His life was exciting, meaningful and ‘almost perfect’. The only thing he lacked was a pious, obedient wife who would give him a lot of lion-like sons and daughters whose beauty would only be matched by their chastity.

Mumtaz looked away from the screen and said, ‘Yuck.’

Lee laughed.

‘This guy could get a degree in self-aggrandisement,’ she said. ‘The kind of woman he wants is a cipher.’

‘Then that is what poor little Mishal must be,’ Lee said.

Abbas al’Barri had come to the office that morning. Delighted that Lee had changed his mind about helping to, hopefully, get Fayyad home, he’d hardly listened to the list of conditions his friend had put on the operation. Lee was sure that Abbas still didn’t know that if Mumtaz felt threatened at any time she’d be able to just stop it. And that was a real possibility.

It had been once Abbas had gone that they’d come up with the name Mishal for their phoney jihadi bride-in-waiting. On the basis that it was about the youngest that Mumtaz could pull off convincingly, they’d decided that Mishal was eighteen. Like Mumtaz, of Bangladeshi heritage, she lived with her parents and two brothers on Brick Lane where her father worked as a minicab driver. It was important to keep as many details as possible close to Mumtaz’s own life story. That way she was less likely to make mistakes in her conversations with Fayyad.

Although ideally they would have wanted her to have an arranged marriage, Mishal’s parents didn’t approve of coercion and were happy to consider any suitable young man she may suggest. Mishal found that very disappointing.

‘They’re being affected by the beliefs of the non-Muslims around them,’ Mumtaz said.

‘Mishal doesn’t approve.’

‘She’s tried to talk to them about it but she finds challenging authority difficult,’ Mumtaz said.

‘Mmm. That’s good. Showing disapproval for their outlandish beliefs but also respecting them because they’re her parents.’

‘Fayyad, or rather Abu Imad, to use his jihadi name, will expect her to transfer that kind of loyalty to him,’ Mumtaz said. ‘He’ll reel her in because she’s questioning her parents’ authority – her dad also takes the odd beer – she’s hormonal, she’s studious and quite lonely. She has recently started to break her parents’ rules, however, by going on Facebook.’

‘So we’ll have to give her “friends” or she’ll have no “profile”. Christ, I sound as if I know what I’m talking about!’

‘Yes, but kids are quite indiscriminate about who they “friend”,’ Mumtaz said. ‘I can “friend” a clutch of Shazia’s distant acquaintances in the certain knowledge they will reciprocate even though they have no idea who Mishal might be.’

Lee sighed. ‘That’s so weird to me.’ Then he asked, ‘Does she cover her head?’

‘Yes, but only in the same way I do. She’d like to go further but she’s worried about what her parents might think. She may well change into niqab when she goes to college.’

‘Does that happen?’

‘Yes,’ Mumtaz said. ‘And in the other direction too. Girls from pious families uncover when they get to college. Shazia has got two friends who do that. One of them has a Lithuanian boyfriend. Lee, do you know anything about Fayyad’s interests? If Mishal is going to make contact with him, then he has to find her, doesn’t he? I mean if she contacts him he may well become suspicious.’

‘He’s the one touting for a bride.’

‘I know, but I think that if he can find her online that will be a lot more convincing than if she contacts him.’

It was a good point. But it would take time. Also, were he in fact reaching out, it may be time they didn’t have.

Lee hadn’t seen Fayyad for at least five years. He said, ‘He was always a big Hammers fan. I don’t know whether that all went out the window when he got religion. And would a girl like Mishal be into football? Wouldn’t it be a bit undignified for her to be looking at all those men’s knees?’

‘Her father is a fan,’ Mumtaz said. ‘She was brought up with the Hammers. She is enormously loyal to the team. But her devotion does give her problems. Only God should be worshipped and Mishal feels that she should really drop her interest in football because she fears it may be sinful.’

Lee shook his head.

‘I know it’s weird,’ she said. ‘But this is how radicalisation, be it Islamist or some other form of brainwashing, works. Gradually the “victim” is distanced from whatever makes her herself until only the ideology is left. If Fayyad is actually trying to make contact with a view to coming home, he will respond to mention of West Ham. It’ll probably be negative, for the sake of his ISIS masters, but it may well mark Mishal out from other potential brides.’

‘As well as her photograph,’ Lee said.

Mumtaz put a hand up to her head. ‘Oh, I’d forgotten about that.’

‘I don’t know how you do modest but sexy …’

‘Oh, not sexy! No!’ she said. ‘God, will I be attractive enough for him …’

‘If you’re not then he must’ve lost his mind …’

‘Be serious!’ she said. ‘And will he believe I’m eighteen? Lee, I am thirty-four! That is geriatric for these people!’

‘Yeah, but you can do younger. I think.’

‘But eighteen? God, this is madness! What am I doing?’

‘You don’t have to do anything,’ Lee said. ‘We’ll stop it. I’ll do it. I’ll—’

‘You can’t!’ she said. ‘And you won’t!’

He said nothing. They sat in silence, stumped by their own fears. However much Lee felt that he owed Abbas, this was proving too hard. It was also potentially dangerous both psychologically and, possibly, physically. ISIS killed people and their reach was long. But then he remembered something.

He said, ‘Photography.’

‘Yes, it’s a problem,’ Mumtaz said. ‘We know that.’

‘Yes, but it could also be another way in,’ Lee replied.

He hadn’t even tried. Shereen threw the graffiti-spattered homework book on the floor. ‘Suk my Cock’, ‘Ass-Fuck’ – it wasn’t even good graffiti. Juvenile and boring. But Shereen knew that the author was far from being a child. Harrison Yates at fifteen was the product of an alcoholic mother, an absent father and a life hanging around the periphery of street gangs, none of whom would accept him. He was one of only five white British boys in Year 10 and he was about to become a father. Why should he bother with his maths homework?