9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

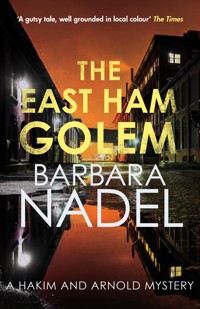

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Hakim & Arnold

- Sprache: Englisch

Irving Levy is a man with few roots and, now that he is terminally ill, is anxious to find anyone to whom he can leave his considerable property. When he learns that there may be more to the disappearance of his younger sister, who disappeared when she was a baby, he engages the services of Hakim and Arnold to investigate. Unwittingly in mortal danger, the private detectives and Levy enter the world of Barking Park Fair and the secrets its brightly coloured attractions conceal. Secrets that lead them not just back to a crime committed in 1963, but to the chaotic world of post-war Europe where few people were what they seemed.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 409

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

DISPLACED

BARBARA NADEL

To my parents, who took me to Barking Park Fair

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

The things people do for money …

There were four freaks, as they called them back then: the Ugliest Woman in the World, the Fattest Woman in the World, a Tattooed Man and the Ling Twins. The first three I could take or leave. Even as a seven-year-old child, I think I knew that there was nothing really that extraordinary about being ugly or fat. Not that the Ugliest Woman in the World was actually that ugly. She had a lot of warts on her face and she smelt, but so what?

It was the Ling Twins that held my attention. Siamese or conjoined twins, or so it seemed: a boy called Ping and a girl called Pong. Names that made me laugh at the time. Heavily made-up, no doubt so they’d look ‘oriental’, it’s unlikely they’d ever seen Brighton, much less Bangkok. And yet at the time I believed they were real with a totality I’ve never experienced since. I think it was probably because Miriam had not long been born. I was finding it hard to adjust to no longer being an only child and so I resented her. Siblings present one with a dilemma. One feels one has to love them and indeed one will do all sorts of things to protect them. But no one can make you like them. Ping and Pong, I believe, made me wonder what it would be like to have never been alone. It was a terrible thought and I clearly remember crying at the time. I also recall being comforted by the Tattooed Man who, by today’s standards, was not very tattooed at all. But he was kind and I appreciated his attention. My mother wasn’t there. She, as I remember it, was screaming outside the freak show tent.

‘My baby! My baby! Someone’s taken my baby!’

ONE

Lee fucking hated modern Cockney rhyming slang. Things like ‘Ronan Keating – central heating’ and ‘Jodie Marsh – harsh’. Daft rhymes bigging up stupid celebrities and other horrible modern obsessions like mobile phones and plastic surgery. But, that said, when he thought about his own current situation he could only say that it had all gone ‘Pete Tong’. It had all gone wrong. Well not everything …

He had money, for once, and he hadn’t had a dream about fighting in Iraq for over a week, so it wasn’t all bad. But it had all gone Pete Tong with Mumtaz and that was the part of his life he cared about most. How could he have been so fucking stupid?

He looked at the small, pale man sitting in front of him and he forced a smile.

‘So, Mr Levy,’ he said, ‘what can I do for you?’

Irving Levy, his potential client, was a small, pale man who could have been anything from fifty to seventy. An Orthodox Jew, he was dressed in a thick black coat and a Homburg hat, although he didn’t have the side-locks characteristic of the ultra-orthodox Haredi sect, which was a mercy. Once, long ago, Lee had been employed to find the errant daughter of one of those and it had been a nightmare. What he could and couldn’t do and when had proved difficult to say the least. But he’d found the girl. Shacked up with a Rastafarian in Brighton. The parents had cried and then declared her dead. Interracial relationships weren’t always easy even in the twenty-first century. He feared this man might have come to him with yet another one.

‘Mr Levy?’

He cleared his throat. ‘You won’t remember this, Mr Arnold,’ he said, ‘I barely remember it myself …’

‘Remember what?’

‘It was 1962. I was seven,’ he said. ‘Which is why I say I barely remember it myself. As you may or may not know, every year there is a fair in Barking Park.’

‘I’ve been a few times, yes,’ Lee said.

The last time he’d gone he’d taken Mumtaz and her stepdaughter, Shazia. They’d all eaten too much candyfloss …

‘My mother took me,’ Levy said. ‘And my sister, Miriam. She was only a baby, one year old. I went on little rides for small children. A carousel, a small railway, as I recall. Then I pestered to see the freak show. One doesn’t find such things these days, they are distasteful. Even then, my mother didn’t approve, but to a child the prospect of seeing the world’s ugliest woman is just too tempting. So she paid for me to go. And I saw the ugly woman, I saw a tattooed man and, to my horror, at the time, I saw Ping and Pong the Siamese Twins. Now of course they were not real – neither twins nor Thai – but they frightened me and I screamed. At almost the same moment my mother, who was outside the tent, screamed too. But for a different reason. She screamed because, having, as she said, turned away from Miriam for a moment, when she looked in her pram the next time, my sister had gone. And, in spite of an extensive police search at the time and in the months that followed, that was the last time anyone in my family saw Miriam. I have cuttings from local papers my parents collected at the time and I’ve written down what I recall about the incident myself.’

He pushed a brown folder across Lee’s desk.

‘Keep them. Look – at the time, the case of my sister’s disappearance was famous. Now it’s just history, but not for me. If Miriam is alive, Mr Arnold, then I want you to find her. And soon. Soon would be best.’

The woman was young and beautiful, but her eyes were ringed with dark circles and she had bitten her nails down to the quick.

‘You will be safe here, Shirin,’ Mumtaz said. ‘I know it’s a bit …’

Her voice trailed off. It had taken the group, known as the Asian Refuge Sisters, a couple of years and a lot of heartache to get hold of this shabby house in Forest Gate. Keeping its location a secret from men who wished to harm the women who lived inside was even harder. But Mumtaz Hakim, private investigator, knew the group well and she trusted them. She’d directed several abused women to their door. But none of them had been from families like that of Shirin Shah.

She looked around the communal living room at the small, covered daughters of Bangladeshi bus drivers and battered Pakistani wives who spoke no English – Shirin stood out like a sore thumb. Tall, slim and wearing very fashionable Western clothes, Shirin came from Holland Park where she had lived with her Harley Street consultant husband in an apartment that was worth millions. Shirin had employed a housekeeper and a chauffeur, and had an account at Liberty in Regent Street. Unfortunately for her, what she didn’t and couldn’t have was children. This had upset her husband who had beaten her mercilessly because of her ‘failure’ to reproduce. Now he wanted to ‘marry’ a second wife who would and could have children. Shirin had refused to accede to this and so he had tried to kill her. But she wouldn’t go to the police, and she wouldn’t tell her parents, and so it was the refuge or nothing.

Mumtaz smiled. ‘Everyone’s very nice here,’ she said.

Shirin looked down at the floor. ‘I can’t share a room. I can’t!’

Mumtaz sat down beside her.

‘Shirin,’ she said, ‘when Muna told me about you, she said you needed somewhere to stay and I’ve found you somewhere.’

Desperate and isolated, Shirin had finally opened up to her hairdresser, Muna, a woman from Manor Park. It had been Muna who had approached Mumtaz for help. The London Borough of Newham had its disadvantages, being one of the poorest districts of the capital was a big one, but it had a sense of community. And everyone in the borough, particularly its women, knew about Mumtaz Hakim, Newham’s only Asian female private investigator.

‘Being here will give you time to think about what you’d like to do next,’ Mumtaz continued. ‘Now you’re no longer under threat from your husband, you can consider maybe who amongst your friends and relatives might help you.’

‘None of them!’

‘You think that now, but you may be surprised,’ Mumtaz said. She held Shirin’s hand. ‘I kept the abuse I suffered at the hands of my husband a secret because I was both ashamed and frightened about what my family might think. But, actually, they were on my side and when my marriage did end, they were devastated that I hadn’t told them.’

‘You have nice parents.’

‘I do. But I’m not alone. There are lots of wonderful parents.’

‘Not mine.’

Mumtaz felt for her. Like her, Shirin was a Muslim and, also like her, her parents were devout. But if they were anything like Mumtaz’s mother and father they were also kind, compassionate and loving. Mumtaz’s husband, Ahmet, had died before she’d admitted his abuse to her father. The old man had cried. ‘If only you had told me,’ he’d said, ‘I could have helped you.’

‘We will see.’

Mumtaz stood.

‘In the meantime, settle in here,’ she said. ‘And I will come and see you again tomorrow.’

‘Thank you.’

The refuge was only minutes from her flat and so Mumtaz decided she’d go home and get a sandwich before returning to work. But then she saw a familiar figure let herself into the flat and she changed her mind. Shazia still wasn’t speaking to her and so it was probably best to leave her alone. She was off to university in Manchester in less than a month, she’d obviously come back to gather more stuff.

Mumtaz wanted to cry, but she pulled herself together and got into her car.

‘I was diagnosed back in January. But I’d not felt well for at least a year.’

‘I’m sorry to hear that,’ Lee said.

He shrugged. ‘It is what it is,’ he said. ‘I’ve had one cycle of chemotherapy, which appears to have worked and so I’m now in what they call remission. May last a few months, years, or the leukaemia may be back tomorrow – nobody knows. But time is a factor, Mr Arnold. Not that I’ve been idle. In amongst all the other tests I’ve had, which have been legion, I’ve also volunteered for a few, which is part of the reason why I’m here today.’

‘Oh?’

‘I got myself a DNA test,’ Levy said. ‘When you’re about to die you wonder who you are. It’s one of those cruel ironies life throws at us.’

Lee knew that one. Before he’d gone to the Middle East to fight Saddam Hussein’s troops in the First Iraq War, he’d never thought about mortality. When he came back, he’d been unable to think about very much else.

‘And what I discovered shocked me.’

‘In what way, Mr Levy?’

‘Irving, please.’

‘Irving.’

‘You look at me and you see an Orthodox Jewish man,’ Levy said. ‘But, unknown to me until I had the DNA test, was that my mother was a Gentile. I knew she was German. The story I grew up with was that she was the daughter of a wealthy pharmacist called Dieter Austerlitz and that she was the only survivor from that family after the Holocaust. But now, of course, I wonder.’

‘Of course.’

‘My father’s family were British Jews,’ he continued. ‘Diamond cutters. That is my trade too. But my mother …’ He shrugged. ‘I do have cousins, on my father’s side, but that is all the family I possess.’

‘You want to know more.’

‘If that is possible, yes,’ he said. ‘But my main aim is to find Miriam. I know I have left it and left it, but life carries one along, don’t you think? Suddenly one finds oneself an old man with no time. Now my only wish, if it is indeed possible, is I would like to see her again before I die. I’d like that she inherit my estate, which is not inconsiderable. I live opposite Barking Park in a house that was recently valued at a million and a half pounds. Then there are my business interests. My cousins are people I barely know. They share only half my blood. Why should they get such a windfall?’

Lee leant back in his chair. ‘Blimey.’

‘A big ask?’

‘I’ll have to review any evidence about your sister’s disappearance from over half a century ago,’ Lee said. ‘There may be leads and there may not be.’

‘I accept that. I’m nothing if not a pragmatist. Dying does that to a person. But Mr …’

‘Lee.’

‘Lee, I have a notion that maybe Miriam’s disappearance was connected to my mother’s real identity. I have no evidence for this and, in fact, the only documents I have been able to find about my mother relate to a person called Rachel Austerlitz of Niederschönhausen district in what later became East Berlin. A Jewish woman and so not my mother.’ He swallowed. ‘My sister Miriam disappeared a few months after her first birthday. We went to the fair as a treat. My mother rarely did such things. Maybe I pestered her?’

‘Did your father go with you?’

‘No, he was working. He always worked, all the time. In the end it killed him,’ Levy said. ‘He died of a heart attack in 1979. My mother died in 2001. To my regret, I never spoke about Miriam to her. I don’t ever remember her speaking about Miriam. My recollection is of my sister disappearing, of my mother crying at the time, and then we had police in our house. But I’ve no idea for how long. I’ve no idea what conclusions, if any, they came to about her. If you’re worried about the cost, then don’t be. I’ve never married, I have no children and I work in a very lucrative trade. My fear is not about penury but about ending my life without making an effort to find my sister. That is what keeps me awake. I know time is short and I often feel unwell. I’m not up to doing this on my own.’

Lee nodded. ‘Do you know how thoroughly the police searched the park?’

‘No.’

‘Because what occurs to me immediately, I’m sorry to say, is the possibility of your sister’s body still being in the ground, in the boating lake or even in what was the old lido,’ Lee said. ‘Of course, I can try and get access to whatever details remain of the investigation, but that doesn’t mean your sister’s body isn’t in that park somewhere.’

‘I understand,’ he said. ‘Sugar-coat nothing. But also, you understand, my budget for this is without limit. I can transfer ten thousand pounds into your account today. This is just to start the investigation.’

‘You don’t—’

‘And I want you to go to Berlin. Hopefully I will be well enough to go too. But that I don’t know. My condition differs from day to day. I want you to find out who my mother was. Find the house where her family lived,’ Levy said. ‘It’s a big job, Lee. You have to find two people: my sister and my mother. In that file I have given you, you will find the story of how my parents met. I have done everything that I can to bring some sense to all this, but now I can go no further without help. I may be in remission, but I’m tired. I just can’t do all this myself. Will you please take my case?’

Crying wasn’t something Shazia Hakim did easily. But looking around her old bedroom made her tear up. The One Direction posters on the walls, her old Blackberry on the bedside table, that stupid Chanel handbag her dad had bought her when she was fourteen …

She picked up the little framed picture Lee Arnold had taken of her and her mum at Barking Park Fair the previous year and she stroked it. What her stepmother had done was wrong, but could she really say she wouldn’t have done the same?

Her dad had been a bad person. There was no getting around it. A gambler who risked his family consorting with gangsters, he’d been a drunk too, and then there had been the sex. When Shazia’s mother had died, he’d turned to her to fulfil his ‘needs’. Then when he’d married Mumtaz, he’d brutalised her. Of course, by that time it was all about money. In debt to a local crime family, the Sheikhs, he’d been out of his mind. Then they’d killed him. Stabbed, in front of Mumtaz, on Wanstead Flats in broad daylight. Only later had Shazia discovered that her beloved Mumtaz, her amma, had let her father bleed to death into the London clay before she even thought to call 999.

Even that she could forgive. But what had driven a wedge between the two women had been Mumtaz’s failure to tell Shazia. This had led to her becoming a pawn in a game between her amma and the Sheikh family, which could have cost Shazia her life. How could Amma have done that? She’d said she’d had no choice and Lee, her amma’s employer, had backed that story up. But Shazia couldn’t and wouldn’t accept it. She’d moved out and was now living with her amma’s parents in Spitalfields. They still didn’t know the truth, but they loved her and were good people. Her adopted grandfather, Baharat Huq, was even going to drive her to Manchester to take up her place there on her criminology degree course.

Shazia opened her wardrobe and took out her winter coat. She’d arrive in Manchester late September, but it was going to be colder up there than it was in London and so she’d need her coat. She put it on the bed together with a couple of shirts and her hair wand. She looked in her jewellery box, but decided she’d only take a couple of pairs of earrings and a big silver filigree ring her friend Grace had given her on her sixteenth birthday. Maybe moving to Manchester would cause her to review her style? Who knew how she would react? Maybe at the end of her course she’d have changed her mind about joining the police?

But then no, that would never happen. Not after what she’d been through and seen. There was more than just a career at stake for Shazia. There was getting even.

She picked up the photograph of herself and her amma, and put it in her bag before she changed her mind.

‘Hi.’

‘Wotcha.’

They shared little except greetings and work stuff, things private investigators needed to share. Lee found it stressful. But how could he even open a conversation about what had happened when she never looked at him? Was she ashamed? He assumed she was, but he didn’t know.

‘How was your …’

‘Fine,’ Mumtaz said. ‘Settled in. She won’t find sharing with others easy, but hopefully she’ll have time to think.’

‘Good.’

‘And you?’

The only way forward was to disappear into the work.

‘Bit of a windfall,’ he said. ‘One job, two cases and a man with some very serious money.’

He told her everything that Levy had told him and then he handed her the pages from the file he’d already examined.

‘When we’ve both read everything he’s given us – there’s not much – we’ll have a chat about where we go from there. It’s not going to be easy,’ Lee said. ‘I’m just going out for a smoke.’

Mumtaz made herself a cup of tea. Lee would be outside smoking for at least twenty minutes, which would give her a good run at this Mr Levy’s notes. But it wasn’t easy for her to concentrate. She knew that Shazia still saw Lee from time to time because her parents had told her. They were friends and she wanted to tell him that it was okay, but she couldn’t. It was ridiculous.

They’d made love. Once. She’d just told Shazia the truth about her father’s death, the girl had stormed out and Lee had turned up to make sure she was alright. It had been passionate, tender and full of love. Only her subsequent guilt had ruined it. And it had – ruined it. He’d bared his soul, he’d told her he was in love with her, and what had she done in return?

She’d pushed him away. Because that was what decent Muslim widows did. Especially widows who had let their husbands die.

She opened Mr Levy’s file.

Father met my mother in September 1945 in Berlin. He was with the British 131st Infantry Brigade and she was living in the cellar of her family’s house in a district called Niederschönhausen. When I was old enough to know about the Holocaust, I asked her how she’d managed to survive when her family had not. All she would ever say was that it was because she was lucky. My father took her out of the ruins of her parents’ house and her life began again. That was all I needed to know.

I have subsequently researched that period of German history a little and have found that actually Niederschönhausen was not in the British but the Russian sector of the city after 1945. How my father came to be in such a place is therefore a mystery to me, as my understanding is that, although the Russians and the other Allied Forces met, control of the various sectors of Berlin was strictly regulated. But I may be wrong.

Through the good offices of the Wiesenthal Centre, I managed to trace some of my mother’s family through both Sachsenhausen and Auschwitz concentration camps. Her mother, Miriam, for whom my sister was named, died in Auschwitz in 1943, along with her husband, Dieter, a pharmacist. My mother’s brother, Kurt, died in Sachsenhausen in 1942. He was eleven years old. There are no records for Rachel Austerlitz, my mother. It seems to me that when her parents and her brother were taken by the Nazis, she disappeared. This fits in with her story such as it was. But how? By 1941 when the family were taken to Sachsenhausen, all Jews in Berlin had been rounded up. How did she evade that?

But here I am assuming that my mother was Jewish, which I now know she wasn’t. Did my grandparents adopt her, maybe? She certainly took their name. The Nazis were nothing if not meticulous and her name is recorded with the other members of her family on a list of Jewish business people working in Berlin in 1937. So far I have been unable to find any other members of the Austerlitz family either living in Germany or Israel. Both my supposed grandfather’s brothers and their families died in Auschwitz too. But my researches are far from extensive, mainly due to my illness. The furthest I have got is to establish that my grandmother Miriam’s original surname was Suskind. These were also business people, employed in the rag trade. The Suskinds in turn were related, through my grandmother’s mother, to a family from Munich called Reichman and also to someone called Augustin Maria Baum. That isn’t the most Gentile name I’ve ever heard, but it comes close. This means that the Suskinds could have had at least one Gentile relation.

A lot of people researched their ancestry via DNA testing. But in Mumtaz’s experience, it often threw up mysteries people hadn’t been expecting and didn’t really want. She knew of two clients whose real fathers had turned out to be strangers from different communities. This had led to strained familial relationships, vicious accusations and bitter guilt.

She glanced at a few small newspaper cuttings about Miriam Levy from 1962, but the details contained in them were minimal. Not much more than a few fuzzy pictures of police officers searching Barking Park.

Lee came back into the office and sat down. He looked at her.

‘Well?’

‘I’ve only got as far as Mr Levy’s own account of his researches and the newspaper cuttings,’ she said. ‘I’ve not looked at any of the documents.’

‘They’re mostly in German,’ Lee said. ‘Just go straight to his translations. But what do you think so far?’

She shrugged. ‘I think it’s a massive job. But, given that Mr Levy is so sick, I think we should maybe concentrate on finding his sister. I mean his family history is fascinating, but …’

‘I agree. But Levy thinks that the disappearance of Miriam and his family history are connected.’

‘Because one of his mother’s ancestors may have been a Gentile?’

‘No,’ Lee said. ‘It’s more to do with the idea that his mother was a Gentile. That her existence was some sort of deception either perpetrated by her or by her parents.’

‘He mentions possible adoption …’

‘Which may have happened.’

‘But if so, then are there any documents to prove it?’

‘Anything where the Holocaust is involved can potentially be a problem, particularly when it comes to finding documents and living witnesses,’ Lee said. ‘The Nazis kept records but, at the end of the war, they destroyed a lot of them. Also, if Rachel was adopted, it may have been unofficial. People just took unwanted kids in back then. My Auntie Margaret was taken in by me gran. I only found that out long after old Auntie Mags had died.’

‘Yes, but this was a wealthy family, so I doubt whether that happened,’ Mumtaz said.

She was right. Where a possible inheritance was involved, people were less inclined to just take unknown children in as their own. It didn’t make sense. Unless …

‘Unless the Austerlitzes took in both kids …’

‘Because Miriam Austerlitz couldn’t have children?’ Mumtaz said. ‘Maybe. But why Gentile children – if indeed Kurt Austerlitz was also a Gentile?’

He shrugged.

She looked him in the eye for the first time in ages and, for a moment, Lee wondered if she might smile at him too. But then she said, ‘So where do we start?’

TWO

‘How fucking old do you think I am, Arnold?’

Lee hadn’t really thought about it until now. Vi was just Vi. Fabulous in her own unique way, but …

‘You were alive in 1962,’ he said.

‘Yes, I was,’ Detective Inspector Violet Collins replied. ‘But I’d only just started primary school.’

‘Oh.’

‘So unless you want me to talk to you about Janet and John or the relative merits of Black Jacks as opposed to Fruit Salads, I won’t have too much to offer,’ she said. ‘Anyway, what do you want to know about 1962?’

Lee put his glass of Pepsi down on the scarred tabletop and watched Vi knock back her second gin and tonic of the evening with envy in his eyes. The Boleyn pub at the top of Green Street in Upton Park had been Lee Arnold’s local, back when he was a soldier with a drinking problem, and then a copper with a drinking problem and a prescription drug issue. Now he was a sober, clean private investigator it was still his preferred boozer although, these days, it was more to do with the fact that the pub would for ever be connected to his favourite football team, West Ham United.

‘A one-year-old baby went missing when the Barking Park Fair was on that year,’ Lee said. ‘Her name was Miriam Levy and she was never found.’

‘Sorry to hear it,’ Vi said. ‘But I’ve never even heard of Miriam Levy. I was probably playing Cowboys and Indians with me brothers at the time. I went to the fair at Barking Park once or twice, but not until the seventies. This is a job …’

‘Yeah,’ he said. He went to the bar and got her another drink, then they both went outside.

Lee lit Vi’s fag and then his own. He said, ‘I know one bloke over at Barking nick, or rather what they call a Police Office over there now. Ronny Brown, but he’s my age.’

‘Can’t help you,’ Vi said. ‘Old Barking nick was shut down. There’s some custody suite down by the Creek and that office, but … Leastways I can’t help you where Plod’s concerned.’

‘Does that mean you might know someone outside the Job?’

She thought for a moment. Then she said, ‘Maybe.’

‘Who?’

She paused again. ‘Leave it with me,’ she said.

Vi knew a lot of people and, although what Lee really needed was information about the police investigation at the time, he left it there for the time being.

When they finished their drinks, he took her home and they went to bed together – as they often did and had done for years, ever since they’d worked together at Forest Gate Police Station.

The Red Army of the Soviet Union captured Berlin from its German defenders in April 1945. They didn’t take just that part of the city that would later become East Berlin, but the whole lot. Only later was Berlin divided up into sectors between the Soviets, the British, the French and the Americans. And so, until the British and other forces arrived in the city in July, the Soviets had the place to themselves. It was an aspect of European history that Mumtaz knew nothing about.

Mumtaz leant against the back of her chair and thanked the Almighty for the Internet. Of course, until she dug somewhat deeper she would only get a sketchy outline of what had occurred in Berlin in 1945. But it seemed that the district of Niederschönhausen, where the Austerlitz family had lived, had not only been taken by the Soviets when they entered the city, but had remained exclusively under their control until the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. So quite how Irving Levy’s father had met his mother under those circumstances, Mumtaz couldn’t fathom. Had Mr Levy senior met Rachel Austerlitz somewhere else in the city? Irving Levy was convinced his father had met his mother in her former home. But was that correct? Over time, the telling of stories altered and, whilst not actually lying, people misremembered and, unconsciously, filled in gaps with events that didn’t happen. As a psychology graduate Mumtaz knew this, but she also wondered whether deliberate lying had taken place too.

Berlin in 1945, from the little she knew about it, had been a place ripe for the production of lies. A conservative estimate of the number of German women raped by the Soviets during the Battle of Berlin was two million. If that wasn’t a motivation to lie, she didn’t know what was. Because Mumtaz had been raped – by her husband – and that wasn’t anything one could tell just anyone, mainly because a lot of people didn’t believe that rape within marriage could exist. A man had his ‘rights’, just like the Soviet soldiers apparently had their ‘reward’ in the shape of German female bodies.

Mumtaz felt cold. Some believed that the Soviet leader, Josef Stalin, had promised his troops ‘Nazi flesh’ as reward for their loyalty and as payment for their own considerable suffering at the hands of Hitler’s army. Some openly admitted that they just did it because they felt like it. But accounts written by German women were scant and, where they did exist, anonymous. Because who could or would own up to being raped by so many men one lost count? Who would own up to the subsequent disease, the abortions and the psychological agony?

No one and especially not, she felt, a woman who called herself Rachel Austerlitz.

Whoever she had been.

The garden was a nightmare. He’d not touched it all year and now bindweed was tapping at the stained-glass window of the downstairs lavvy. Not that the house and its considerable gardens had ever been exactly elegant – it hadn’t. But until he’d got sick, Irving had managed it.

He’d not changed anything. He had maintained it and he had sorted out his parents’ possessions when they died. Now it looked like one of those houses where hoarders lived with junk piled up at the windows and weeds creeping across the pathways. He’d seen programmes on TV about it. People who wasted their lives looking after dreck.

Had he wasted his life? He probably had, but what could you do? Like his father he’d spent every waking hour looking at, shaping and caressing some of the most magnificent stones the earth had ever produced. Stones worth millions. But he’d never had kids. He’d never even gone out with a woman.

If he were dishonest with himself, he’d blame his parents. Always shouting at each other, arguing over nothing, dragging him into their fights as each tried to get the upper hand. But what was that? A detail. If he’d really wanted to go out and find a life for himself, he could have done. The truth was that he was lazy. Better stick with the things he knew – warring parents, a house stuck in the 1950s and the blinding glitter of diamonds.

Right at the very back of his memory, he could just recall a time when his parents had behaved differently. Way before the fighting and the screaming – and Miriam. Was he wrong when he thought that all the really mad times came after she had been born? And disappeared?

Of course, the disappearance of a child was enough to send anyone round the bend and so that must have been the beginning of things going downhill. When his mother had got pregnant he must have been five, but he remembered nothing about it. All he really remembered about that time was the fair, the Ling Twins and his mother screaming as if she was being murdered.

Her dadu wanted her to make things up with her amma. Of course he did! Not that he knew anything about it. Both Shazia and her amma had told the old couple nothing. Shazia looked at the photograph Lee had taken of her and her amma at Barking Park Fair the previous year and she shook her head. Soon it would be fair time again, but she wouldn’t go.

That evening had been such fun. Amma had gone on the dodgems where she’d proved herself to be quite the demon driver and had almost tipped Lee out of his car. They’d all got candyfloss round their mouths and she’d almost been sick when she went on the waltzer after eating the greasiest doughnut she’d ever had. Amma and Lee had kept on looking at each other the way her mate Grace used to look at her old boyfriend Mamba, and so she’d tried to give them some time to be alone together. She’d never been on so many rides on her own or gone to the toilet such a lot.

It had, however, been during one of these jaunts to the loo that she’d got scared. Making her way past the helter-skelter and through the maze of caravans at the back of the site, she’d found herself alone between two vast low-loaders. She’d obviously taken a wrong turn somewhere along the line and was about to choose which direction to take when a wizened figure approached her dressed in a silk dressing gown. At first, it had said nothing, but then as it, or as she later deduced she, got closer, the figure said, ‘Are you lost?’

Shazia had smiled. A tiny old woman with a face like a brown leather pump was coming to help her.

‘I’m looking for the toilet,’ she’d said.

‘Oh, I see,’ the old lady had said. ‘Is not far. Let me take you.’

‘Thank you.’

The woman’s voice was high-pitched and possessed an accent that Shazia couldn’t place. Not that she spoke again. She simply took Shazia’s arm in one tiny hand and began to guide her past the low-loaders and out into the tangle of caravans. Threading an eccentric course between what were people’s homes, Shazia couldn’t help but look into windows where people were cooking, washing, having arguments and, in one case, kissing. She felt guilty. Why did people always feel they could look in through a lit window?

Shazia, ashamed, lowered her gaze, which was when she noticed the old woman’s hand. Holding her elbow tight in what was a hard, sinewy grip, the hand was small, brown, withered and had the longest, most malformed fingernails Shazia had ever seen. Bright yellow and with the consistency of horn, these nails curled and twisted seemingly random courses away from her fingers, often resulting in vast circles as they came to sharp points at each tip.

Fascinated but also a little scared, Shazia let herself be led by the woman until, or so it seemed, the noises from the fairground had almost receded to nothing. When she looked up again she found herself standing outside a small shed. This, she surmised, was probably, if not the toilet, then a toilet. It certainly wasn’t the one she’d been to before.

She’d thanked the woman before she noticed that she was no longer holding her elbow. Now she had the toilet door open and was smiling a toothless grin, ushering Shazia forward with one bizarre, horn-encrusted hand. Shazia, her heart hammering, thought about just running, but now she really did want to go to the toilet and so, slowly and cautiously, she went inside and locked the door. Only once she’d finished did she hear laughter outside. Some weird old fairground type had clearly had a right laugh freaking her out. Fairground people were notorious for playing tricks on their punters and the boys who operated the waltzer always got girls pregnant. Or so Grace said.

But when she left the cubicle, Shazia found that she was alone. She was also just steps away from the fairground where she could see Lee and her amma watching the brightly coloured carousel whirl round, carrying laughing children riding metal horses.

Shazia had looked back once to see whether the old woman was still around, but she only saw darkened caravans.

She’d said nothing to either her amma or to Lee, but the experience had stayed with her and, in a way, she felt glad that she wouldn’t be going to the fair again this year. She’d be in Manchester, or at least preparing for her new life there, away from the East End, her past and the woman who had been both more cruel and more kind than anyone else she had ever known. Amma, who had lied to her. Amma, who she loved more than her life.

THREE

‘You want that, love? I got a lot of different sizes, colours …’

Mandy was tempted to ask the man who’d taken the lime green miniskirt she’d glanced at briefly off the dress rail what he thought an overweight woman in her forties might do with such a thing. Wear it as a belt? But she just smiled and said, ‘No, thanks.’

Taking a trip round Barking Market was more a case of giving herself something to do than actually shopping, for Mandy Patterson. A chance to get out of her office on slow days. Several sizes too big for any of the ordinary clothes stalls, Mandy didn’t fancy going to what she called the ‘fat bird’s shop’ with all its ‘freesize’ stuff from Italy and trousers that could be seen from space. Occasionally she’d get something from one of the greengrocers, maybe a type of vegetable Ocado didn’t have in stock.

She was looking at a load of dodgy pashminas when her phone rang. She shoved it underneath her chin and answered.

‘Mandy Patterson.’

‘Hiya, Mand.’

God, she knew that deep, dark-brown, common-as-shite voice.

‘Lee,’ she said. ‘What’s the problem?’

‘No problem,’ he said.

‘So you’re alright? You’re not …’

‘No, Mand,’ Lee Arnold said. ‘I haven’t had a drink; I don’t want a drink.’

‘Good.’

Mandy had been Lee’s AA sponsor when he’d given up the booze and, over the years, they’d become, albeit infrequent, mates.

‘What I’m actually after is a meet up,’ Lee said.

‘Because?’

She knew he had an ulterior motive. Though her friend, Lee always did. But then maybe all PIs were like that?

‘Something that may be of mutual interest has come up,’ Lee said. ‘How you fixed for dinner tonight?’

‘Where?’

‘New Moroccan place has opened up in Stratford, called Baba Ganoush. My shout.’

Oh, he knew her weak spots. She was a sucker for a tagine. He had her and he knew it. But still she had to make him work for it.

She said, ‘What makes you think I’m free tonight?’

‘Oh, well, if you’re not … Well …’

‘And yet sadly and tragically we both know that you know that I am,’ Mandy said. ‘Pick me up at eight and you have a date.’

She heard him laugh. ‘Handsome.’

Mandy ended the call and went back to looking at the schmutter on display in the market. Maybe, she thought, I should buy that lime green miniskirt. That’d frighten the bugger.

Lee put his phone back in his coat pocket and then sat down on a bench overlooking the boating lake. He lit a cigarette.

‘She could be in there,’ he said, pointing at the water.

Mumtaz sat down beside him.

‘Or anywhere in the park,’ she said.

She hadn’t been back to Barking Park since she and Lee had visited the funfair with Shazia almost a year ago.

‘Do you think that your reporter friend will be able to put you in touch with ex-employees?’

‘Mandy’s a good girl and if there’s a story in it for her, she’ll pull out the stops.’

‘Yes but, Lee, is there a story?’ Mumtaz said. ‘I mean, do you know whether Mr Levy will want his family history splashed across the local press?’

‘I don’t think he’ll care if it gets results.’

‘You must check it with him.’

He looked at her and said, ‘Yes, Mum.’

She looked away. She hadn’t slept after reading about the terrible events that had occurred in Berlin in 1945. Some of the German women had been raped thirty times, many of them had died. Then she’d gone first thing to see Shirin Shah at the hostel. When she’d arrived the girl had been crying. She’d told Mumtaz that she couldn’t stand the hostel, that she wanted to go home. It had taken all Mumtaz’s powers of persuasion to make her stay. Her head was still not in the right place. She still saw her failure to conceive as her main problem.

‘What about the police reports?’ she said.

‘I’m working on it.’ He smoked. ‘I never had much to do with Barking nick when I was in the Job, but Vi’s looking into it. I doubt whether there’s many blokes still alive from that time.’

‘What about the fair?’

‘Well that changed hands,’ he said. ‘Used to be run by a family called Mitchell, but they were bought out by a company called Lesters in the eighties. They’re due to hit town on Monday 19th September.’

‘I thought the fair didn’t come until later in the month?’

‘Not this year. Dunno why. Brexit?’

Mumtaz shook her head. Ever since the referendum on British membership of the European Union had produced a negative result, people who had wanted to remain, like Lee and Mumtaz, had started to blame everything on those who wanted to leave.

The park was quiet. Apart from a few joggers and a small group of dog walkers, they almost had the old Victorian park to themselves. A large green open space in the middle of a packed, still mainly poor, if changing, London borough, Barking Park’s main attractions – the boating lake and a splash park – were aimed at kids who were clearly spending their summer holidays elsewhere.

‘Whoever took Miriam could have buried her body anywhere here,’ Mumtaz said as she looked at the vast areas of grass, trees and water around her. ‘And when the fair left, its vehicles would have churned the ground up so much, how would anyone have even known where to dig?’

‘Unless it was hot that year.’ He threw his dog-end on the ground and stamped it out. He said, ‘This is a big job and so I’m gonna get some of the casuals in to do the day to day so you and me can concentrate on this.’

Process serving and performing background checks, the bread and butter of PI work, carried on in spite of bigger, more lucrative investigations.

‘Lee, do you think that Miriam Levy could still be alive?’

‘Her brother thinks she could and so we have to assume it’s possible.’ He shook his head. ‘I think, he thinks that because his mother wasn’t who he thought she was, Miriam’s disappearance is connected to that.’

‘But if she was just taken …’

‘We don’t know that she was,’ he said. ‘That’s what Irving Levy says, and what he says and the truth may be very different things.’

Mumtaz shook her head. They were due to meet Mr Levy at his house on Longbridge Road in an hour. Although, according to him, he’d shown them everything he’d managed to find regarding his sister, Irving Levy felt it was important for Lee and Mumtaz to see where she had lived.

After a pause, during which he considered changing the subject to something more personal, Lee said, ‘I googled Irving’s house. It’s bloody massive.’

Croydon was one of only two venues the fair went to that was close to London. The other one was Barking. Back in the old days when Lesters Fair had been Mitchells they’d gone right in to Clapham Common. But old Mr Lester had been a country boy born and bred, and he’d changed the original routes to, largely, give the capital a wide berth. His son, Roman, hadn’t altered things when he’d taken over in the noughties. So when first Croydon and then Barking came on the horizon, teenage fairground kids like Amber Sanders became excited.

‘Lulu and Misty are going to go to Camden Market,’ she told her mother, Gala, as they packed away and secured the crockery in the caravan’s small kitchen. Just because Guildford was only thirty-four miles from Croydon, didn’t mean they didn’t have to carefully wrap up all their belongings and secure the fittings in their caravans.

‘Are they.’

Amber knew from her mum’s tone of voice that meant that she wouldn’t be able to join her friends. Not unless she bunked off.

‘Misty is twenty now,’ Amber said. ‘So she’s not, like, a kid any more …’

‘She isn’t, no,’ her mother said. ‘But you are. You know the rules, Amber, no one goes off site until they’re eighteen unless it’s with their parents.’

‘So you take me!’

She wrapped a Royal Wedding commemorative plate from 1981 in tissue paper and slid it carefully into its original box.

‘And when am I going to do that, eh?’

‘I dunno. In the daytime, when you’re not working?’

‘You mean when I’m working, or looking after you and your dad, or helping Mama take care of Nagyapa?’

Amber pulled a face. ‘She can manage on her own for a few hours. If Nagyapa knows you need to take time off for me …’

‘You think?’ Her mother turned away. ‘Just because you twist him around your little finger. I’m not talking about this any more.’

‘Yeah, but—’

‘Yeah, but nothing. Get on with the packing. We need to be on the road first thing tomorrow morning and I haven’t even started putting the clothes away.’

Amber pulled a face, but she did as she was told. Her great-grandfather, Nagyapa, had been bed-bound for years and now, at ninety-three, needed round-the-clock care. This was mostly done by her grandmother, Eva, or Mama as her mum called her. Nagyapa had been in circuses when he was young. He’d been a trapeze artist in a circus back in his native Hungary. When she was little he’d shown Amber lots of old photographs of himself and his little brothers and his sister flying in space across the great, grand circuses that had travelled across Europe in the 1930s and 40s. But then World War II happened and he’d ended up in England, a middle-aged man with