Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Emma Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Serie: The Emma Press Prose Pamphlets

- Sprache: Englisch

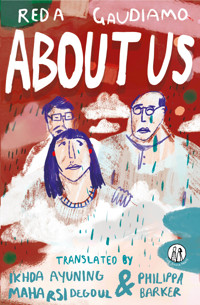

Now's not the time to think. Now's the time to feel. A taxi ride, a train trip, a family photo: in About Us, seemingly unremarkable journeys and mundane objects ripple with the repercussions of past decisions. All is not what it seems at a family wedding, a regretful father risks estranging his daughter, and a young woman is tormented by the cries of a baby that her partner cannot hear. Reda Gaudiamo's characters charm, chafe and confound in a series of intimate snapshots of domestic relationships. With twists shifting from the comically mischievous to the abruptly chilling, this collection is a bold slice of contemporary Indonesian literature.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 236

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

AUTHOR’S NOTE

The 17 short stories in this book are a collection of my works from the 1990s to 2015. All of them were first published in print magazines in Indonesia, as well as on my social media channels.

The inspiration for the stories comes from eavesdropping on public transportation, articles in newspapers, strangers I met in coffee shops, and my own family. Thank you for letting me write them down to be read by many.

I’d like to thank the Emma Press, who believed in this collection and decided to publish it in English. Thanks to Ikhda Ayuning Maharsi Degoul and Philippa Barker, who translated these stories so beautifully.

Thanks to the editors, Georgia Wall and Emma Dai’an Wright, for being so patient with me.

Thanks to Amy Louise Evans for her beautiful artwork for the cover.

And thanks to all the beloved readers who decided to read these stories from Indonesia. Enjoy!

Reda GaudiamoJAKARTA, 2023

OTHER TITLES FROM THE EMMA PRESS

SHORTSTORIESANDESSAYS

Parables, Fables, Nightmares, by Malachi McIntosh

Blood & Cord: Writers on Early Parenthood, edited by Abi Curtis

How Kyoto Breaks Your Heart, by Florentyna Leow

Night-time Stories, edited by Yen-Yen-Lu

Tiny Moons: A year of eating in Shanghai, by Nina Mingya Powles

POETRYCOLLECTIONS

Europe, Love Me Back, by Rakhshan Rizwan

POETRYANDARTSQUARES

The Strange Egg, by Kirstie Millar, illus. by Hannah Mumby

The Fox’s Wedding, by Rebecca Hurst, illus. by Reena Makwana

Pilgrim, by Lisabelle Tay, illustrated by Reena Makwana

One day at the Taiwan Land Bank Dinosaur Museum, by Elīna Eihmane

POETRYPAMPHLETS

Accessioning, by Charlotte Wetton

Ovarium, by Joanna Ingham

The Bell Tower, by Pamela Crowe

Milk Snake, by Toby Buckley

BOOKSFORCHILDREN

Balam and Lluvia's House, by Julio Serrano Echeverría, tr. from Spanish by Lawrence Schimel, illus. by Yolanda Mosquera

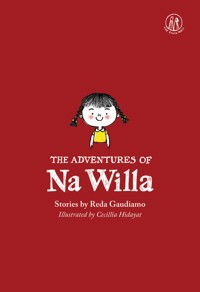

Na Willa and the House in the Alley, by Reda Gaudiamo, translated from Indonesian by Ikhda Ayuning Maharsi Degoul and Kate Wakeling, illustrated by Cecillia Hidayat

We Are A Circus, by Nasta, illustrated by Rosie Fencott

Oskar and the Things, by Andrus Kivirähk, illustrated by Anne Pikkov, translated from Estonian by Adam Cullen

For my family: where life begins and love never ends.

THEEMMAPRESS

First published in the UK in 2023 by the Emma Press Ltd.

Originally published in Indonesia as Tentang Kita by Stiletto Book in 2015.

Stories © Reda Gaudiamo 2015.

English-language translation of ‘Ayah, Dini and Him’, ‘Maybe Bib Was Right’, ‘Her Mother’s Daughter’, ‘Family Portrait’, ‘About Us’, ‘24 x 60 x 60’, ‘The Little One’, ‘The Trip’, ‘Baby’, ‘Son-In-Law’, ‘Taxi’ and ‘Dawn on Sunday’ © Ikhda Ayuning Maharsi Degoul and Philippa Barker 2023.

English-language translation of ‘I Am a Man’, ‘An Apology’, ‘Cik Giok’, ‘Our World’ and ‘One Fine Morning’ © Ikhda Ayuning Maharsi Degoul 2023.

Edited by Georgia Wall and Emma Dai’an Wright.

Cover design © Amy Louise Evans 2023.

All rights reserved.

ISBN 978-1-912915-13-2

EPUB 978-1-915628-18-3

A CIP catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library.

Printed and bound in the UK by youloveprint, East Sussex.

The Emma Press

theemmapress.com

Birmingham, UK

Contents

Ayah, Dini and Him

Maybe Bib Was Right

Her Mother’s Daughter

Family Portrait

About Us

24 x 60 x 60

The Little One

The Trip

Baby

Son-In-Law

Taxi

Dawn on Sunday

I Am a Man

An Apology

Cik Giok

Our World

One Fine Morning

Acknowledgements

About the author

About the translators

Also from the Emma Press

Publication of this book was made possible, in part, with assistance from the LitRI Translation Funding Program of the National Book Committee and Ministry of Education and Culture of the Republic of Indonesia.

Ayah, Dini and Him

1. Ayah1

The rain is heavy outside, rays of sunlight reflecting off the deep puddles that run like rivers down the street. If anyone dared to cross it, they’d be soaked through at once. A year ago, on a stormy night like this, Dini ran away from home, slamming the door behind her. I should have called out to her, pleaded with her to come inside. I could have gone after her, fetched her back home.

I should have reached for her hand, pulled her close and wrapped her shivering body in a towel. I should have told her, ‘Here now, we can put this behind us. We were both angry. Please, forget what I said. Go take a bath before you catch a cold.’ And I can picture her smiling up at me, wiping away her tears.

That’s what I should have done, but it didn’t happen like that. Instead I just sat there, glued to my seat, lips tightly sealed as my fingers gripped the pipe I’d stopped smoking. I didn’t move to go after her, didn’t say a single thing to bring her back. Dini left and didn’t return, and hasn’t stepped foot in this house since that day.

I heard about her graphic design business from friends of hers I ran into at the market. I was glad to know it was going well, that a recent collaboration had paid off. But when it used to rain like this, back when Dini still came home to visit me, she would put out two glasses of sekoteng and snacks made by Bik Nah, our household help. We would sit together and talk, watching the downpour. Listening to the sound of rain was our secret hobby, our favourite pastime. We loved the atmosphere it created; how it was loud and intense, but also calming. Our conversation always ended up on the same topics: art, design, film, sometimes politics and education too.

We made a good team, Dini and I; we were alike in so many ways. What I’d give now to talk to her again, just the two of us watching the rain. But maybe what I want even more than that is for her to find another man to confide in, a partner for the rest of her life.

‘You know, Dini, when you get married someday, our rainy day chats will have to end. Your future husband might not share our hobby,’ I told her one cloudy evening.

‘Well, guess what? When I get married, I’m going to choose a man just like you, Ayah. And I won’t let him interfere with my hobbies. He’ll just have to learn to like rainstorms too,’ she said heatedly.

‘What, you really want to marry a man like me? I’ll tell you this: there is no one like me in the whole universe. And even if there was, where would be the fun in that? You’ll get bored of me eventually.’

She shook her head. ‘I’ll never get bored with you, Ayah. And I will find someone who is just like you. And when I do, I won’t have to spend time getting used to them, because I know I like you already.’

‘Ah, so you just want the easy option?’

‘Don’t you want me to be happy?’ She stared at me with her big round eyes, something in her expression reminding me of her mother. She reached out and hugged me, planting a kiss on my cheek. ‘Just you wait and see – my boyfriend will be just like you, Ayah!’ Then she released me. ‘It’s still raining. I want another glass of sekoteng. Do you want more too?’ She got up. I could tell she was bored of all our talk of future husbands.

That wasn’t the first time we’d talked about when she might settle down and find a husband. We often discussed it, though I was always the one who brought it up. But still the subject was never settled, always skidding to a halt at the same point: she would only consider marrying a man like me. I told myself that things would work themselves out, that she’d find someone eventually. I’ll admit I grew impatient though, waiting for that day to arrive.

Dini never brought up the word ‘boyfriend’ or mentioned any relationships. I knew she had lots of male friends, though she never seemed to pay them much attention. Now she was twenty-five and had finished her studies the previous year, I wondered whether she would finally start to show some interest. She might have seemed indifferent to the idea, but it nagged at me all the time, until one day I began to suspect that there might be someone after all.

I don’t recall exactly when, but at some point a particular name began to crop up in Dini’s life. While Dini’s other male friends rarely came up in conversation, this man was mentioned more and more often.

Every Saturday, and sometimes on a Friday afternoon when Dini was able to finish work at her studio in Jakarta early, she would come home to Bogor to visit me. But now the evenings we spent together, catching up on each other’s lives as we walked the quiet streets of Sempur, were shared by the three of us. Me, Dini, and him.

We could still talk about the same things, because he claimed to have the same interests as Dini and me. But when our talk drifted onto the topic of graphic design, he began to dominate the conversation, like he couldn’t contain his opinions a moment longer. Knowing the field quite well, I didn’t buy everything he said, whereas Dini, who’d studied visual and graphic design for years at the Institute of Technology in Bandung, couldn’t stop asking him questions, hanging off his every word.

What had happened to my bright girl who could think for herself? Had she forgotten everything she’d learned? Dini lapped up every supposed fact and figure that fell from his mouth. I grew tired of his foolishness, tired of watching Dini say ‘Oh!’ and ‘Wow!’ and ‘Really?’ over and over, like she was stuck on repeat. Once, when my ears were unable to listen to him rattle on a moment longer, I excused myself early, hoping that Dini would take the hint and ask him to call it a night. But without me there, their conversation became even more lively, his voice growing in volume as he told story after story.

Back in my room, I could still hear Dini’s laughter. Rage thumped in my chest as I thought about how he’d deliberately and skilfully ejected me from the conversation with his tedious talk about graphic design, and then moved on to other topics once I’d gone. I was going to have to keep an eye on him, that was for sure.

Lying awake in the middle of the night, I listened to the sound of Dini’s laughter as it carried through the house. Though the room was dark, I saw my bedroom door slowly open as Dini peered inside. I quickly shut my eyes and pretended to be asleep, until I heard the door swing shut again.

‘You’d better stay with me, Yos,’ she whispered, failing to suppress a giggle. ‘Ayah is fast asleep and snoring already.’

Snoring? Me? How dare you, Dini!

2. Dini

It’s hot as a sauna outside, though it’s been raining for four solid days now. Luckily Bang Ucup helped me check the roof of my studio last week, or there might have been trouble.

The din of water falling on the rooftops tells me the rain is still heavy. But with the street empty of people, it’s also eerily quiet. As I sit and listen to the rain, coffee growing cold, my thoughts drift to Ayah. I picture him sitting in the living room of our family home, sipping on a glass of sekoteng, a plate of fried sweet bananas on the table beside him. I wonder if he still enjoys a good rainstorm like we used to.

This wasn’t always our favourite pastime. It began twelve days after Ibu, my mother, was buried. When the rain that had started early in the morning showed no sign of stopping, Ayah decided to stay home for the day. I remember he sat in the living room flipping through an old magazine of Ibu’s, his gaze occasionally drifting to stare out the window. With no interesting books to read, I resorted to playing ‘Autumn Leaves’ – Ibu’s favourite song, which I knew by heart – on the piano till I got bored.

I sat down next to Ayah. Unable to find any words, neither of us said anything for a while, until we both took a breath at the same time. Ayah smiled at me before he began to talk.

‘It’s so calm, isn’t it, Dini?’

‘Yes, Ayah. I can’t stop thinking about Ibu. Are you thinking about her too?’

He nodded. ‘Come, tell me a story, Din.’

His request surprised me. ‘What kind of story, Ayah?’

‘Anything you like. You used to love chatting with your mother. What kind of things did you share with her?’

It felt strange, talking to Ayah like that. It was as though I was in front of a stranger – I didn’t know what to say. But he was patient, encouraging me to try talking to him instead now that Ibu was gone.

And so I began to share every bit of my life with him: stories about my school friends, the stern teachers, my ever-growing pile of homework, and my worries about the upcoming exams. When it was his turn, he told me about his work, letting me into the art world I had always been so curious about.

Ibu had always told me that Ayah’s job was boring, though Ayah did his best to defend it, trying to convince me of its appeal. He would often keep himself busy in the room Ibu nicknamed his ‘warehouse’, though Ayah had made a sign saying ‘studio’ and fixed it to the door. Sometimes his friends would come and visit his studio, to take a look at his work. I could tell that this made him happy because of the smile on his face after their visits.

On the last day of rain after Ibu’s passing, I came to appreciate Ayah’s job in all its wonder. I finally saw how, with paint, a brush and canvas, you could create the most beautiful artworks. When I graduated from high school a year later, I broke the promise I had made to Ibu to go on to study economics and chose fine art instead.

To my surprise, Ayah disagreed, insisting that I keep the promise I’d made to Ibu all those years ago. He was angry when he found out that I’d only applied to study fine art at the Institute of Technology in Bandung, and nowhere else.

‘If there are still private universities open for a second wave of applications, I’d like you to apply, just in case.’ He looked serious. ‘Only applying to ITB... I’m sorry, but I’m not happy about that.’

I couldn’t figure him out. It was Ayah who had unlocked my passion for art. Now I’d fallen in love with it and didn’t want to let go of my dream, he was forcing me to leave it behind.

‘But why, Ayah?’ The deadline for the second wave of applications had passed already. Plus, deep down, I knew I didn’t want to go to any other university. I cried every day for a week as I argued with him, until finally something in his heart melted. From then on, we resumed our conversations about art as if nothing had happened. I left for university soon after, and then after graduating I got a job in a small studio in Jakarta.

I was quite sure that I would never find a man as great as Ayah, until Yos came into my life. He arrived at a time when I desperately needed someone to help me design adverts in the studio. Sure, I had friends who came and helped out, but they were students, like I had once been. Reliable only until exams started, when they would leave the studio to study.

I finally decided to put an advert on the information board at Graha Bhakti Budaya opera house. It was small, almost invisible among the many others. By the seventh day, when there were still no applications, I had almost given up. But then on the eighth Yos arrived.

‘I’ll be honest with you, I don’t have any formal education in graphic design,’ he said in the interview.

‘I don’t mind that. What I’m interested in is your style, creativity and work ethic. Also, your relationships with clients. I’m a small business owner and I care about my clients. We work very closely with them on projects.’

‘I can’t guarantee that my style will be to your taste, but if you give me some work I’ll show you what I can do. Here, look at my portfolio. And in terms of collaboration, I’m always professional in my relationships. Nothing more, nothing less.’

‘And you’re disciplined?’

‘I meet all my deadlines, if that’s what you mean.’

He smiled at me.

At that moment, I knew I’d chosen the right person. He was the man I wanted to work with. Yos always came up with brilliant ideas, things I’d never thought of before. With simple tools and equipment, he was able to tackle complicated tasks. Not to mention his passion for photography.

‘Yos, what made you want to work here?’ I asked one day. ‘With your skills, you could have found a good position at a big advertising agency where you’d get paid millions of rupiahs.’

‘It wasn’t for me, Dini,’ he said. ‘They’re looking for highly-qualified fine art graduates, but they also want you to specialise. Their art directors don’t get to do photography as well as drawing and writing. But I like doing all those things. And anyway, they don’t hire people over 30 for starter roles. Honestly, I almost gave up trying to find a new job after leaving my publishing position, and then I saw the advert you’d put in Taman Ismail Marzuki.’

‘Well that would have been daft! What if I hadn’t hired you? What would you have done then?’

‘Probably the same as I’ve always done – just taken the first job I found. The pay can be good. But it’s so tiring – jobs come and go so fast. Nothing’s certain,’ he said, laughing. He told me stories about his time at other jobs and things that had gone wrong, though he made them sound funny rather than traumatic.

The studio always kept us busy. Sometimes we stayed late to finish projects, working through to the early hours of the morning. Those nights brought us closer together, and then one day Yos told me about his feelings for me. Fortunately, or perhaps unfortunately, since we were co-workers, I felt the same for him. I was nervous, wondering how I’d tell Ayah. I wanted Ayah to know that I’d met a smart, skilful, knowledgeable, kind man, just like him. How happy he would be, I thought. I wanted to tell him right away.

But I was wrong. Not only was Ayah displeased when I told him about Yos, but he was actively against him. And just like when I’d chosen to study at ITB, Ayah insisted that I let Yos go.

‘Find another man. Whoever you want, but not this man.’

‘Why? What’s wrong with Yos? You don’t even know him. You don’t see his talent. I see you in him. Of course, you’re not exactly the same, but he –’

‘Please stop comparing us, Dini. You need to find the best way to end your relationship with him. There are many talented people in this world who would make good co-workers. I can help you find a replacement, if you want.’

‘I’m not doing anything until you tell me why you hate Yos.’ My voice was trembling and I could feel tears welling in my eyes, but I refused to back down – not until I understood why Ayah felt the way he did. But he wouldn’t explain his reasoning, and just carried on insisting.

‘Ayah, you’re not going to back down, but nor will I. Don’t be surprised if I marry Yos one day!’

‘You wouldn’t dare, Dini.’ His voice grew sharp, his eyes turning cold with hurt.

‘Why not? You’ll see!’

‘You’re so stubborn! But you’ll regret it, I guarantee it!’

‘I won’t! You’ll be the one who’s sorry!’

It rained heavily that night. I’d told Ayah my news, thinking it would make him smile. I’d imagined him hugging me tight and kissing my cheek, full of joy. But it hadn’t gone like that at all. Unable to stop my tears from falling, I grabbed my bag and ran from the house, out into the downpour. All the while Ayah sat in his chair, glued to the spot.

3. Dini and Him

‘Yos, you startled me!’

‘I knew you wouldn’t have gone to bed yet. I always know where you are when it’s raining like this. Sat by the window, lost in your thoughts.’

‘Will you sit with me for a bit? There’s ginger tea in my blue Thermos if you want some?’

‘Of course. It’s ok, I can get it.’

‘Yos, I can’t stop thinking about Ayah.’

‘He’s probably thinking about you too right now. Think about how long it’s been since you left. You don’t even send him updates, poor guy.’

‘If he wants to talk, he can come to me. He’s the reason I left.’

‘But you’re his only child. You know what his temper’s like. Why don’t you reach out to him?’

‘No way. Not until he writes me a letter, or calls and explains everything.’

‘Everything?’

‘Yes, everything about you, about us!’

‘Ah, so it’s that. He must have a good reason for not liking me. Parents always have strong views, especially about their future sons-in-law.’

‘Don’t you mind that he hates you?’

‘Of course I do. I’m not thrilled about it. You did warn me about what he was like, though. But the way he’s gone about things, trying to split us up... Of course it hurts. Why do you think he hates me so much, Din?’

‘I’ve got no idea. I just can’t think why.’

‘Maybe he hates smokers?’

‘Nonsense. He used to smoke a lot himself. He still loves smoking his pipe. He always said he’d stop, but he still hasn’t. No, he definitely doesn’t hate smokers.’

‘Maybe it’s because I’m from a different ethnicity and background to him?’

‘But that’s ridiculous. Ayah and Ibu weren’t of the same ethnicity. It never bothered him before.’

‘Maybe it didn’t back then, but he could have changed his mind. Maybe he secretly hoped his son-in-law would come from the same place as him, so he’d know his family and background already?’

‘I’m telling you, it doesn’t matter to him!’

‘Hey, for all we know that could be the reason, Dini.’

‘Maybe. But if it was, it would scare me how narrow-minded and petty he’d become.’

‘Look, I can’t pretend to know what’s going on in his head. But I’m sure it hurt him a lot.’

‘Yos, I don’t want us to...’

‘Let’s not overthink it. Everything will be fine.’

‘But how?’

‘We’ll go and see him.’

‘You really want to?’

‘Yes. I mean, why not? Maybe he’ll explain himself.’

‘No, I don’t think I can face it.’

‘What are you afraid of? I haven’t done anything wrong. I just want to know the truth. If he has a good reason and I agree with him, then maybe we’ll have to reconsider our relationship.’

‘Hang on, what? You would really do that?’

‘Let’s be realistic, though. It’s probably just a misunderstanding.’

‘So –’

‘So, I’d like to go and see your father, if I may? I can go on my own, or would you rather come with me?’

‘Errr...’

‘Though maybe it’s better if you don’t come.’

‘Yes, I’d prefer to wait here.’

‘Okay then. That’s what we’ll do.’

4. Ayah and Him

‘What are you doing here? Is Dini not with you? Don’t tell me she’s too scared to see me?’

‘She’s tied up at the studio, Pak.’2

‘Well then, how can I help you?’

‘I’ve come because I want answers. I know you don’t approve of our relationship. You’ve made it very clear you don’t like me and Dini being together. But I want to know why.’

‘It’s not something I’m willing to discuss any further.’

‘Why not?’

‘Because I don’t want to.’

‘But how can I begin to understand things from your point of view if you won’t at least explain? You must see that your decision doesn’t just affect you. It affects Dini and me, and we have a right to know.’

‘Don’t try and manipulate me.’

‘You’ve put me in this position, Pak.’

‘It’s not easy to explain. I wouldn’t know where to start.’

‘I’ll listen. I’ll try to understand.’

‘Are you serious about Dini?’

‘Yes, Pak, I’m serious.’

‘Do you love her? Will you support her, wherever life takes her?’

‘Yes, with all my heart and soul.’

‘Are you sure?’

‘Yes.’

‘You and your big head. You’re just an employee in her business. Did you know she founded the studio all by herself? She used her own money, plus a little from her mother. And then you came along, got a job there, told her you love her, and now I hear you plan to marry her. You think everything’s going to be rosy, don’t you? Are you really that stupid?’

‘What? I don’t understand –’

‘You’ve got no idea how strong and tough my little girl is. She’s ambitious, just like her mother. Whatever she sets her mind to, it’s hers. She’s always been successful, up to now. Always.’

‘She’s an incredible woman.’

‘I couldn’t agree more. But then I see who you are. Dini’s told me all about you. You’re all she’s talked about these past few months, before she left. I’ve heard all about your failures. I’ve heard all about the countless jobs you’ve had, and yet here you are with nothing to show for it. And now you, you with your fancy adverts, you dare to take my talented daughter away from me. I can’t believe your nerve!’

‘Pak…’

‘Don’t interrupt me. I know what’s going to happen next. This is all going to end in tears. I’m sorry, but you’re on a sinking ship. I know because I was in the same position myself once. I don’t want that life for my daughter.’

‘Maybe it was you who got it wrong, Pak.’

‘How dare you!’

‘I’m sorry, Pak, but how can you know what tomorrow will bring? You seem so confident in predicting where our relationship is headed, but it’s our life, mine and Dini’s, not yours. Yes, I work for Dini, but it doesn’t mean I’m beneath her. We do different tasks according to our skills, but we see each other as equals. We’re not just co-workers, we’re partners. If you think I begged her to take me on, or that I’m holding her back, you’re wrong. And as for what ‘we’ are, we’re not just co-workers. We are lovers who work together. And we’re determined to take the business forward and keep getting better.’

‘Big words, Yos!’

‘Pak –’

‘Listen to me. They used to be my words too. I used to say the exact same things. That’s right. We’d say them too, me and Mira, Dini’s mother. Decades ago, before we were even married, we had exactly the same dream as yours. Mira loved my paintings – she wanted to open a gallery to show off my work. But it never happened. My paintings couldn’t provide enough for us to live on. Mira had to find a different job to help keep us afloat. And she was good at it, getting promotion after promotion while my paintings faded into obscurity. People saw me as the man who lived off his wife’s earnings. They judged me for that, and they were right. Mira was the one bringing in the money. She was the one responsible for providing for our family all those years. She paid for Dini’s education. I never contributed a penny. But Mira, she never complained. She always told me how proud she was of me, of my paintings. But how could I believe her? Deep down, I knew how disappointed she was with me. How frustrated she was with the way life had turned out.’

‘Did you ever talk to her about it?’

‘What would have been the point? To upset her further? No. I already knew how she felt. The proof came when she suggested we keep Dini away from the art world, in case she decided she wanted to be an artist too. We could see she had a natural talent for it, but I didn’t want her to have the same experience as I had. We wanted Dini to live a good life, to thrive and be successful, to find a man who would make her happy. I can’t bear to see our life story repeat itself in hers.’

‘But, Pak –’