Table of Contents

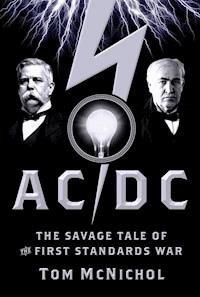

Title Page

Copyright Page

Prologue

Chapter 1 - FIRST SPARKS

Chapter 2 - LIGHTNING IN A BOTTLE

Chapter 3 - ENTER THE WIZARD

Chapter 4 - LET THERE BE LIGHT

Chapter 5 - ELECTRIFYING THE BIG APPLE

Chapter 6 - TESLA

Chapter 7 - THE ANIMAL EXPERIMENTS

Chapter 8 - OLD SPARKY

Chapter 9 - PULSE OF THE WORLD

Chapter 10 - KILLING AN ELEPHANT

Chapter 11 - TWILIGHT BY BATTERY POWER

Chapter 12 - DC’S REVENGE

Epilogue

Further Readings in Electricity

The Author

Index

Fig. 4.—Experiments in Killing Animals by the Alternating Current, as Conducted in the Edison Laboratory at Orange, N. J.

Copyright © 2006 by Tom McNichol. All rights reserved.

Published by Jossey-Bass A Wiley Imprint 989 Market Street, San Francisco, CA 94103-1741 www.josseybass.com

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, 978-750-8400, fax 978-646-8600, or on the Web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, 201-748-6011, fax 201-748-6008, or online at www.wiley.com/go/permissions.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a professional where appropriate. Neither the publisher nor author shall be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages.

Readers should be aware that Internet Web sites offered as citations and/or sources for further information may have changed or disappeared between the time this was written and when it is read.

Jossey-Bass books and products are available through most bookstores. To contact Jossey-Bass directly call our Customer Care Department within the U.S. at 800-956-7739, outside the U.S. at 317-572-3986, or fax 317-572-4002.

Jossey-Bass also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

McNichol, Tom.

AC/DC : the savage tale of the first standards war / Tom McNichol. p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-7879-8267-6 ISBN-10: 0-7879-8267-9

1. Electric currents, Alternating—History. 2. Electric currents, Direct—History. 3. Electricity—Standards—History. 4. Electricity—History. I. Title. QC641.M36 2006 621.319’ 1309—dc22 2006013041

Prologue

NEGATIVE AND POSITIVE

I’ve always had a healthy respect for electricity. Twice, it almost did me in.

The first time was serious. I was eleven years old, hanging out with my friend Mike in his basement. We had liberated some of his father’s tools from a chest and were happily drilling, hammering, and sawing away the afternoon. I picked up a staple gun, which I had never used before, and began firing wildly like a Wild West gunslinger. There was a powerful recoil every time you shot a staple, so it seemed like you were doing something significant when you squeezed the trigger.

Looking around, I noticed that some insulation in the ceiling was sagging a bit—nothing a dozen well-placed staples couldn’t fix. I dragged a metal chair under the spot, climbed on top, and with one arm stretched over my head Statue of Liberty style, began shooting staples into the insulation. It was difficult to aim while balancing on the chair, and one of the staples became embedded in a dark brown cord that ran along the edge of the ceiling. I’ll just pull that staple out with my hand, I thought.

The brown cord turned out to be a wire buzzing with 120 volts of electricity, the standard household current in the United States. When I touched the metal staple rooted in the wire, my body became part of the electrical circuit. The current raced into my hand, down my arm, across my chest, down my legs, through the metal chair and into the ground—all at nearly the speed of light.

The sensation of having electricity course through your body is hard to put into words. Benjamin Franklin, who was once badly shocked by electricity (though not while flying a kite), described the feeling in a letter to a friend: “I then felt what I know not how to describe,” Franklin wrote. “A universal blow throughout my whole body from head to foot, which seemed within as well as without.”

A blow that seemed “within as well as without”: yes. To me, the shock felt as though it was not simply running along the surface of my skin but was burrowing deep inside my body. The current felt like hot metal had been poured into my veins, a powerful surge that raced into the bones and down the marrow. The electricity was entering my body through my hand, but it didn’t feel like the current had any particular location. It was everywhere. It was me.

The electricity flowing through my body was encountering resistance, which in turn was converted to heat. When people talk about criminals being “fried” in the electric chair, it’s a fairly accurate description of what actually happens. I was slowly but steadily being cooked alive.

I’m not sure how long my hand clutched the electrified staple. Perhaps only a few seconds; maybe longer. Time seemed to have a different quality while in electricity’s grip. The burst of current contracted the muscles in my hand, causing me to grasp the staple even harder, a phenomenon noted by Italian physician Luigi Galvani in the late eighteenth century when he touched an exposed nerve of a dead frog with an electrostatically charged scalpel and saw the frog’s leg kick.

When a human touches a live wire, electricity often causes the muscles in the hand to contract involuntarily, an unlucky condition known among electrical workers as being “frozen on the circuit.” Victims frozen on the circuit often have to be forcibly removed from the wire since they’re unable to exercise control over their own muscles.

I was lucky. Just as my fingers were curling into a tight fist around the hot electrified staple, the sharp contraction of the muscles in my arm jerked my hand free. I immediately fell to the floor—pale, panting, and dazed, but otherwise uninjured. I had just felt the power of AC, or alternating current, the type of electricity found in every wall outlet in the home. In an AC circuit, the current alternates direction, flowing first one way and then the other, flipping back and forth through the wire dozens of times per second.

The 120 volts of electrical pressure that come out of an AC wall outlet are more than sufficient to kill a human being under the right circumstances. More than four hundred Americans are killed accidentally by electricity every year, and electric shock is the fifth leading cause of occupational death in the United States. And yet alternating current is utterly indispensable to modern life. The world as we know it simply couldn’t do without AC power. Every light bulb, television, desktop computer, traffic signal, toaster, cash register, refrigerator, and ATM is powered by alternating current. The Information Age is built squarely on a foundation of electricity; without electric power, bits can’t move, and information can’t flow. Even the bits themselves are tiny electrical charges; a computer processes information by turning small packets of electricity on and off.

My second encounter with electricity’s dark side wasn’t quite as serious, but still left its mark. I was in college trying to jump-start my car on a frigid day, and had just attached the jumper cables to the battery of another car. As I moved to clamp the other end of the cables onto the dead battery, I stumbled and inadvertently brought the two metal clamps together. Once again, I had completed an electrical circuit, and once more, I was caught in the middle of it. A brilliant yellow-blue spark leaped from the cables, accompanied by a loud “pop.” I immediately dropped the cables and discovered a black burn mark on my hand the size of a quarter, a battle scar from the electrical wars.

This time, I had been done in by DC, or direct current, the kind of current produced by batteries. Direct current moves in only one direction, from the positive to the negative terminal, but beside that, DC is the same “stuff” as AC: a flow of charged particles. A car battery produces about 12 volts of electrical pressure, only onetenth the power that comes out of an AC wall outlet, but that didn’t make my hand feel any better. Under the right conditions, direct current is every bit as deadly as alternating current.

And yet DC is also utterly essential to contemporary life. Every automobile on the road depends on DC to operate, along with every cell phone, laptop computer, camera, and portable music device. The same force that strikes people dead in lightning storms also saves lives. Cardiac defibrillators deliver a controlled burst of direct current to heart attack victims, forcing the heart muscles to contract and resume a regular rhythm.

Life and death, negative and positive. Electricity has many dualities, so it’s only fitting that the struggle to electrify the world would give birth to twins: AC and DC. Long before there was VHS versus Betamax, Windows versus Macintosh, or Blu-ray versus HD DVD formats, the first and nastiest standards war of them all was fought between AC and DC. The late-nineteenth-century battle over whether alternating or direct current would be the standard for transmitting electricity around the world changed the lives of billions of people, shaped the modern technological age, and set the stage for all standards wars to follow. The wizards of the Digital Age have taken the lesson of the original AC/DC war to heart: control an invention’s technical standard and you control the market.

The AC/DC showdown—which came to be known as “the war of the currents”—began as a rather straightforward conflict between technical standards, a battle of competing methods to deliver essentially the same product, electricity. But the skirmish soon metastasized into something bigger and darker.

In the AC/DC battle, the worst aspects of human nature somehow got caught up in the wires, a silent, deadly flow of arrogance, vanity, and cruelty. Following the path of least resistance, the war of the currents soon settled around that most primal of human emotions: fear. As a result, the AC/DC war serves as a cautionary tale for the Information Age, which produces ever more arcane disputes over technical standards. In a standards war, the appeal is always to fear, whether it’s the fear of being killed, as it was in the AC/DC battle, or the palpable dread of the computer age, the fear of being left behind.

1

FIRST SPARKS

The story of electricity begins with a bang, the biggest of them all. The unimaginably enormous event that created the universe nearly 14 billion years ago gave birth to matter, energy, and time itself. The Big Bang was not an explosion in space but of space itself, a cataclysm occurring everywhere at once. In the milliseconds following the Big Bang, matter was formed from elementary particles, some of which carried a positive or negative charge. Electricity was born the moment these charged particles took form.

All matter in the universe contains electricity, the opposing charges that bind atoms together. Even human beings are awash in it; the central nervous system is a vast neuroelectrical network that transmits electrical impulses across nerve endings to the body’s muscles and organs.

However, electricity, like the face of the Creator, is normally hidden from view. Most matter contains a balance of positive and negative charges, a stalemated tug-of-war that prevents electricity from manifesting itself. Only when these charges are out of balance do electrons move to restore the equilibrium, allowing electricity to show its face.

Electrical current is the flow of negatively charged electrons from one place to another in order to restore the natural balance of charge. It would take untold years and thousands of lives before humans learned to harness that flow and make those unseen charged particles do their bidding. Even then, electricity remained shrouded in mystery, an eccentric, invisible force with powers that seemed to come from another world.

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!