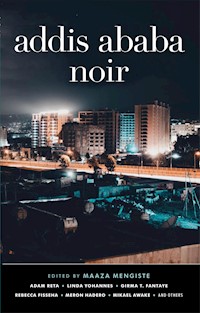

Addis Ababa Noir E-Book

15,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: CASSAVA REPUBLIC

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

What marks life in Addis Ababa are the starkly different realities coexisting in one place. It's a growing city taking shape beneath the fraught weight of history, myth, and memory. It is a heady mix. It can also be disorienting, and it is in this space that the stories of Addis Ababa Noir reside . . . These are not gentle stories. They cross into forbidden territories and traverse the damaged terrain of the human heart. The characters in these pages are complicated, worthy of our judgment as much as they somehow manage to elude it. The writers have each discovered their own ways to get us to lean in while forcing us to grit our teeth as we draw closer . . . Despite the varied and distinct voices in these pages, no single book can contain all of the wonderful, intriguing, vexing complexities of Addis Ababa. But what you will read are stories by some of Ethiopia’s most talented writers living in the country and abroad. Each of them considers the many ways that myth and truth and a country’s dark edges come together to create something wholly original—and unsettling.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

ADDIS ABABA NOIR

EDITED BY MAAZA MENGISTE

ALSO IN THE AKASHIC NOIR SERIES

ALABAMA NOIR, edited by DON NOBLE

AMSTERDAM NOIR (NETHERLANDS), edited by RENÉ APPEL AND JOSH PACHTER

ATLANTA NOIR, edited by TAYARI JONES

BAGHDAD NOIR (IRAQ), edited by SAMUEL SHIMON

BALTIMORE NOIR, edited by LAURA LIPPMAN

BARCELONA NOIR (SPAIN), edited by ADRIANA V. LÓPEZ & CARMEN OSPINA

BEIRUT NOIR (LEBANON), edited by IMAN HUMAYDAN

BELFAST NOIR (NORTHERN IRELAND), edited by ADRIAN McKINTY & STUART NEVILLE

BERKELEY NOIR, edited by JERRY THOMPSON & OWEN HILL

BERLIN NOIR (GERMANY), edited by THOMAS WÖERTCHE

BOSTON NOIR, edited by DENNIS LEHANE

BOSTON NOIR 2: THE CLASSICS, edited by DENNIS LEHANE, MARY COTTON & JAIME CLARKE

BRONX NOIR, edited by S.J. ROZAN

BROOKLYN NOIR, edited by TIM McLOUGHLIN

BROOKLYN NOIR 2: THE CLASSICS, edited by TIM McLOUGHLIN

BROOKLYN NOIR 3: NOTHING BUT THE TRUTH, edited by TIM McLOUGHLIN & THOMAS ADCOCK

BRUSSELS NOIR (BELGIUM), edited by MICHEL DUFRANNE

BUENOS AIRES NOIR (ARGENTINA), edited by ERNESTO MALLO

BUFFALO NOIR, edited by ED PARK & BRIGID HUGHES

CAPE COD NOIR, edited by DAVID L. ULIN

CHICAGO NOIR, edited by NEAL POLLACK

CHICAGO NOIR: THE CLASSICS, edited by JOE MENO

COLUMBUS NOIR, edited by ANDREW WELSH-HUGGINS

COPENHAGEN NOIR (DENMARK), edited by BO TAO MICHAËLIS

DALLAS NOIR, edited by DAVID HALE SMITH

D.C. NOIR, edited by GEORGE PELECANOS

D.C. NOIR 2: THE CLASSICS, edited by GEORGE PELECANOS

DELHI NOIR (INDIA), edited by HIRSH SAWHNEY

DETROIT NOIR, edited by E.J. OLSEN & JOHN C. HOCKING

DUBLIN NOIR (IRELAND), edited by KEN BRUEN

HAITI NOIR, edited by EDWIDGE DANTICAT

HAITI NOIR 2: THE CLASSICS, edited by EDWIDGE DANTICAT

HAVANA NOIR (CUBA), edited by ACHY OBEJAS

HELSINKI NOIR (FINLAND), edited by JAMES THOMPSON

HONG KONG NOIR, edited by JASON Y. NG & SUSAN BLUMBERG-KASON

HOUSTON NOIR, edited by GWENDOLYN ZEPEDA

INDIAN COUNTRY NOIR, edited by SARAH CORTEZ & LIZ MARTÍNEZ

ISTANBUL NOIR (TURKEY), edited by MUSTAFA ZIYALAN & AMY SPANGLER

KANSAS CITY NOIR, edited by STEVE PAUL

KINGSTON NOIR (JAMAICA), edited by COLIN CHANNER

LAGOS NOIR (NIGERIA), edited by CHRIS ABANI

LAS VEGAS NOIR, edited by JARRET KEENE & TODD JAMES PIERCE

LONDON NOIR (ENGLAND), edited by CATHI UNSWORTH

LONE STAR NOIR, edited by BOBBY BYRD & JOHNNY BYRD

LONG ISLAND NOIR, edited by KAYLIE JONES

LOS ANGELES NOIR, edited by DENISE HAMILTON

LOS ANGELES NOIR 2: THE CLASSICS, edited by DENISE HAMILTON

MANHATTAN NOIR, edited by LAWRENCE BLOCK

MANHATTAN NOIR 2: THE CLASSICS, edited by LAWRENCE BLOCK

MANILA NOIR (PHILIPPINES), edited by JESSICA HAGEDORN

MARRAKECH NOIR (MOROCCO), edited by YASSIN ADNAN

MARSEILLE NOIR (FRANCE), edited by CÉDRIC FABRE

MEMPHIS NOIR, edited by LAUREEN P. CANTWELL & LEONARD GILL

MEXICO CITY NOIR (MEXICO), edited by PACO I. TAIBO II

MIAMI NOIR, edited by LES STANDIFORD

MILWAUKEE NOIR, edited by TIM HENNESSY

MISSISSIPPI NOIR, edited by TOM FRANKLIN

MONTANA NOIR, edited by JAMES GRADY & KEIR GRAFF

MONTREAL NOIR (CANADA), edited by JOHN McFETRIDGE & JACQUES FILIPPI

MOSCOW NOIR (RUSSIA), edited by NATALIA SMIRNOVA & JULIA GOUMEN

MUMBAI NOIR (INDIA), edited by ALTAF TYREWALA

NAIROBI NOIR (KENYA), edited by PETER KIMANI

NEW HAVEN NOIR, edited by AMY BLOOM

NEW JERSEY NOIR, edited by JOYCE CAROL OATES

NEW ORLEANS NOIR, edited by JULIE SMITH

NEW ORLEANS NOIR: THE CLASSICS, edited by JULIE SMITH

OAKLAND NOIR, edited by JERRY THOMPSON & EDDIE MULLER

ORANGE COUNTY NOIR, edited by GARY PHILLIPS

PARIS NOIR (FRANCE), edited by AURÉLIEN MASSON

PHILADELPHIA NOIR, edited by CARLIN ROMANO

PHOENIX NOIR, edited by PATRICK MILLIKIN

PITTSBURGH NOIR, edited by KATHLEEN GEORGE

PORTLAND NOIR, edited by KEVIN SAMPSELL

PRAGUE NOIR (CZECH REPUBLIC), edited by PAVEL MANDYS

PRISON NOIR, edited by JOYCE CAROL OATES

PROVIDENCE NOIR, edited by ANN HOOD

QUEENS NOIR, edited by ROBERT KNIGHTLY

RICHMOND NOIR, edited by ANDREW BLOSSOM, BRIAN CASTLEBERRY & TOM DE HAVEN

RIO NOIR (BRAZIL), edited by TONY BELLOTTO

ROME NOIR (ITALY), edited by CHIARA STANGALINO & MAXIM JAKUBOWSKI

SAN DIEGO NOIR, edited by MARYELIZABETH HART

SAN FRANCISCO NOIR, edited by PETER MARAVELIS

SAN FRANCISCO NOIR 2: THE CLASSICS, edited by PETER MARAVELIS

SAN JUAN NOIR (PUERTO RICO), edited by MAYRA SANTOS-FEBRES

SANTA CRUZ NOIR, edited by SUSIE BRIGHT

SANTA FE NOIR, edited by ARIEL GORE

SÃO PAULO NOIR (BRAZIL), edited by TONY BELLOTTO

SEATTLE NOIR, edited by CURT COLBERT

SINGAPORE NOIR, edited by CHERYL LU-LIEN TAN

STATEN ISLAND NOIR, edited by PATRICIA SMITH

ST. LOUIS NOIR, edited by SCOTT PHILLIPS

STOCKHOLM NOIR (SWEDEN), edited by NATHAN LARSON & CARL-MICHAEL EDENBORG

ST. PETERSBURG NOIR (RUSSIA), edited by NATALIA SMIRNOVA & JULIA GOUMEN

SYDNEY NOIR (AUSTRALIA), edited by JOHN DALE

TAMPA BAY NOIR, edited by COLETTE BANCROFT

TEHRAN NOIR (IRAN), edited by SALAR ABDOH

TEL AVIV NOIR (ISRAEL), edited by ETGAR KERET & ASSAF GAVRON

TORONTO NOIR (CANADA), edited by JANINE ARMIN & NATHANIEL G. MOORE

TRINIDAD NOIR (TRINIDAD & TOBAGO), edited by LISA ALLEN-AGOSTINI & JEANNE MASON

TRINIDAD NOIR: THE CLASSICS (TRINIDAD & TOBAGO), edited by EARL LOVELACE & ROBERT ANTONI

TWIN CITIES NOIR, edited by JULIE SCHAPER & STEVEN HORWITZ

USA NOIR, edited by JOHNNY TEMPLE

VANCOUVER NOIR (CANADA), edited by SAM WIEBE

VENICE NOIR (ITALY), edited by MAXIM JAKUBOWSKI

WALL STREET NOIR, edited by PETER SPIEGELMAN

ZAGREB NOIR (CROATIA), edited by IVAN SRŠEN

FORTHCOMING

ACCRA NOIR (GHANA), edited by NANA-AMA DANQUAH

BELGRADE NOIR (SERBIA), edited by MILORAD IVANOVIC

JERUSALEM NOIR, edited by DROR MISHANI

MIAMI NOIR: THE CLASSICS, edited by LES STANDIFORD

PALM SPRINGS NOIR, edited by BARBARA DeMARCO-BARRETT

PARIS NOIR: THE SUBURBS (FRANCE), edited by HERVÉ DELOUCHE

TABLE OF CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Howling in the Darkness

The faint bedroom light spilled across the floor and slumped against the window. I stood with my ear plastered to the wall, my hands shaking. I heard it again. The growls that darkness could not swallow. I knew what it was. I knew what they were. They were back and there was nothing we could do to stop them. When daylight came, I would walk outside, go down the steps of our veranda, and I would see the hole and the blood and the fur and other discarded parts of the dog that was now missing. I knew where the hyenas came from. I’d been warned to stay away from the forest that began just down the road from our house. The mouth of that forest was a wide cluster of trees intersected by bands of light. The dark patches were large enough to swallow a grown man and make him disappear. And this was another lesson I would learn very soon: that people, too, disappeared.

It was 1974 or it might have been 1975. I was too young to pay attention to years, to understand the sweep of time. I measured days by the nights that fell on us and brought in darker things: revolution and soldiers and curfews and gunfire. Somewhere in between this, the hyenas started coming to eat our dogs. They did this one night at a time. Taking the first and leaving the other two alive to witness their methodical hunger. To froth and whine and jump in mindless fear. They returned soon for the next one, sending the sole survivor into maddened, writhing terror while it waited for the inevitable. They were unstoppable. Every night, as shots rang out between revolutionaries and government forces in those early years of the Ethiopian Revolution, the hyenas clawed beneath the fence my grandfather tried in vain to reinforce. They were diligent. They worked on our fence to get beneath it, then crawled into our compound and found a way into the cage where the dogs were kept and they ate until there were none left.

Let me tell you another story: There are men who live in the mountains of Ethiopia and can turn into hyenas. This fact has always been a part of my knowledge of the world: There are men who can shift bodies and disappear into another form. And as 1974 crept forward and 1975 swept in, as our dog cage remained empty and the revolution ramped up, I began to wonder if all those disappeared people—those I saw one day then did not see again, those whose names adults tried never to speak in my presence—were, in fact, simply changing shape to avoid government forces. Maybe, I used to think, they would eventually find a way back home—but this time, as hyenas. These are some of my early memories of Addis Ababa, but they are not the only things I remember from that time. I had a childhood cushioned by protective parents, loving aunts and grandparents, and neighborhood friends. The brightness of those moments helped to balance the darkness of those other facts of living. What marks life in Addis Ababa, still, are those starkly different realities coexisting in one place. It’s a growing city taking shape beneath the fraught weight of history, myth, and memory. It is a heady mix. It can also be disorienting, and it is in this space that the stories of Addis Ababa Noir reside.

Ethiopia is an ancient country with a long and storied history. It has been both a geographic location and an imaginative space for millennia. Herodotus writes of it in his Histories, Homer and Virgil reference a region of the same name. Ethiopia and its people can be found in several books in the Bible. It is a country that has reshaped and remolded itself over thousands of years through conquest and conflict, through sheer will and relentlessness. Those who reside within its borders—those relatively new lines of demarcation—are multiethnic and speak over eighty languages and more than two hundred dialects. The present view of Ethiopia is often stunningly narrow when set against its rich historical and cultural heritage. And now imagine that these varied, proud, and robust cultures have wound their way into Addis and made it home. There is a cosmopolitanism that is distinctly national as much as international. To meet someone from Addis Ababa, with its three million–plus inhabitants, may not tell you much about that person. But to meet someone from one of its neighborhoods—Ferensay Legasion or Lideta or Bole or Kechene or Bela Sefer or any of the areas where these stories in Addis Ababa Noir are set—may give you a better map leading to more fruitful details. The authors in this anthology extend a hand to you. Let them lead you down their streets and alleyways, into their characters’ homes and schools, and show you all the hidden corners, the secrets, and the lapsed realities that hover just above the Addis that everyone else sees.

These are not gentle stories. They cross into forbidden territories and traverse the damaged terrain of the human heart. The characters that reside in these pages are complicated, worthy of our judgment as much as they somehow manage to elude it. The writers have each discovered their own ways to get us to lean in while forcing us to grit our teeth as we draw closer. Sulaiman Addonia, Lelissa Girma, and Hannah Giorgis write compellingly about the visceral and horrifyingly high costs of love and desire. In language that is as supple as it is evocative, Mahtem Shiferraw, Girma T. Fantaye, Mikael Awake, and Adam Reta render mythic worlds that mirror our own with some startling—and often bloody—differences. Solomon Hailemariam, Bewketu Seyoum, and Linda Yohannes focus their perceptive, unflinching gazes on the sometimes humorous, sometimes deadly unpredictability of city life. Teferi Nigussie Tafa explores with stark clarity what happens when ethnic-based tensions and violence are compounded by the onset of the 1974 revolution. This revolution also plays a pivotal role in the haunting stories by Meron Hadero and Rebecca Fisseha. And despite the varied and distinct voices in these pages, no single book can contain all of the wonderful, intriguing, vexing complexities of Addis Ababa. But what you will read are stories by some of Ethiopia’s most talented writers living in the country and abroad. Each of them considers the many ways that myth and truth and a country’s dark edges come together to create something wholly original—and unsettling.

Maaza Mengiste

Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

PART I

PAST HAUNTINGS

KIND STRANGER

by Meron Hadero

Lideta

Addis Ababa was hardly recognizable, a city casting itself into a new mold: taller, more modern, more planned and plotted. I’d gotten used to crossing construction sites with big boulders and chiseled stone, so I was surprised when I tripped. Looking down, I saw a reclining man reaching for me. His head leaned toward his legs, his hands outstretched and clasping. He looked familiar, though it was unlikely that I actually knew him—I lived in the States now, and rarely made it back. It was hard to see him clearly in the long afternoon shadow of the cathedral. I knelt beside him to make sure he was okay.

“Are you hurt?” I asked, and tried to lift his head. I thought about calling for help, but he started talking without any introduction.

“Listen, my child.” His voice was barely a whisper so I had to bend down. “One night near the end of the rainy season, I got caught in a storm,” he told me.

I reached into my shoulder bag to offer him some water, but he shook off the gesture and kept talking.

“I found myself jumping over the flooded gutters as I ran from the minibus toward home with my jacket over my head to keep myself a little drier, but you know how it is with the rainy season—a losing battle. The whole bus ride, I had to fight for space next to a boy and his damp, smelly goat; that boy showed no respect for his elders standing next to me like that. I was tired, and there was the boy and his soggy little beast, and the rain, and outside there were rows of yellow Mercedes, which I always thought I’d look quite good driving.”

I was surprised by this deluge of narrative coming from a stranger, and then tried to do what I thought I should: I felt his forehead, which wasn’t hot. I checked his pulse, which didn’t race. I rolled up my sleeves and sat down beside him. I tried telling him to take it easy, but he had more to say.

“So that night was—how do they say it in the movies?—a dark and stormy night,” he went on in English.

“A dark and stormy night,” I repeated. “That’s what they say.”

“Besides the rain, the power outage made it hard to see except for the bursts of lightning that lit up the street, lit up the homes, lit the acacia trees on the hillside. The lightning flashed just as I was about to take out my keys and open the gate, and that’s when I saw her: Marta Kebede standing under a big black umbrella, looking the same as the day she was arrested back in 1980. I hadn’t heard of her or seen her since, though I’d thought of her often, of course.”

With the words “of course,” I knew I had to interrupt, because I thought, This man has mistaken me for someone else. He said “of course” like I knew him well, like none of this should come as a surprise to me, and on top of that, the way he leaned his head close and whispered into my ear felt intimate, as did the soft way he grasped my hand. The only thing I could think of worse than unrequited intimacy was mistaken intimacy.

“Sir, I think you have me confused with someone else,” I told the man. “Just rest. I think you’re hurt. Let me get you a car. I could give you some money.” When he declined, I looked again for a wound or sign of injury, but couldn’t find any.

He didn’t seem moved by my concern and just said, “If you have a minute … I just need to rest a minute. If you have a minute, I will take that.”

I didn’t really have time to spare. This was a short visit to see relatives, and almost every moment was accounted for. Yet I felt like I should stay with him just a little longer.

He didn’t wait for my response and simply continued his story: “So I’d just seen Marta, the first time in decades, and there she was, caught in the middle of a storm. The lightning stopped for a moment and I could no longer see her silhouette. I tried to speak into the darkness, but thunder smothered my hello. I jogged toward where she had stood, moving with both excitement and hesitation, for the sight of her made me feel conflicting emotions: elation, dread, and also grief. Isn’t that the way it is with grief, though? First we mourn the grief we bear, and then later we mourn the grief we’ve caused.”

As he said these words, the helplessness on his face that I’d taken for kindness seemed to vanish. I thought that this switch was strange, that his emotions could change so easily, so suddenly and completely.

“So that night on that dark street, I called out again to Marta, saying the only words I could think of: ‘Let’s go for dinner.’ It was an awkward thing to say, but once I had said something, I started saying everything. ‘It’s me, Gedeyon. Don’t you remember? We were students in the same class at university—you were getting your degree in pharmacology, and I was studying chemistry. I asked you out on a date the first week, and you said no, and you made fun of my shoes, saying that they were farmer shoes, and that you wouldn’t date a boy with farmer shoes because your father would kick you out of the house and your mother would drag you to the priest and drown you in holy water. I saved up a whole half year to buy new shoes, really nice ones, and I asked you out again, and you didn’t know who I was. I told you I was going to be a professor and you said you wouldn’t go out with me, but this time you didn’t bother with a reason. I guess I must have loved you. How else could I explain the lengths I went to get your attention, your approval? I wish it hadn’t happened that way, and I still wonder if we would have turned out differently if things happened some other way.’ Isn’t that a lot to say into the darkness?” Now he gripped my arm and lifted himself onto the boulder to sit upright.

“Yes, it is a lot to say.” In any light, I thought.

“If she had acknowledged me, if things had gone a little differently between us, maybe I wouldn’t have accused her. Did you ever live here during the Derg?” he asked, not giving me much time to consider what he’d just revealed. “I think you didn’t. I think you lived somewhere Western, some wealthy country with peace and freedom.”

“I know the Derg,” I replied. “I was a child of the Derg, born of that era.”

Gedeyon shook his head. “Those of you who left here when you were young, without a scratch, and had the luxury of living somewhere else don’t know what some of us carry. You know what the Derg technically is, but you don’t truly know. You know the Derg as a definition, a Cold War junta that lasted too long and did too much harm. But those of us who got to truly know the Derg, who knew it as an uninvited guest dropping in on each meal and in every interaction, well …”

I felt my face flush, and now it was the grip of guilt that kept me there as he went on.

“I had been tortured by the Derg—that’s how I got to know it. Some of the students avoided school back then to reduce the risk of being arrested and just stayed home. But I was poor. I went to school every day, whether there was a demonstration or the threat of arrest or nothing at all because we got free lunch at the university, and if I didn’t go, I didn’t eat all day. It was a simple fact of life. So I went to school every day and was arrested, and who knows why back then. Maybe I had a friend or associate who was suspicious, or maybe my hair was too long or too short, or my fingernails were too clean or too dirty. Maybe it was on account of my nice new shoes—who knows? But when the Derg interrogated me, lashing my feet, asking me to name names to get myself free, I gave them Marta’s name. She was wealthy, had power, and I thought she could escape, that she’d have a better chance of surviving it than I would. And it’s not that I hated her, but she’d stung me. Marta had stung me. Those subtle stings to pride—they’re worse than the big ego blows because they’re not like some obvious pebble you can remove from your shoe. They are like shards that you know are there but can’t find and can’t get rid of. Oh, Marta, I wish she’d never made fun of my shoes.”

“So did Marta accept your dinner invitation during the thunderstorm?” I asked, trying to keep him awake since I saw his eyelids beginning to droop.

“Well, I kept asking her to dinner, but she didn’t say anything. I stood there waiting for another bolt of lightning, and when it came, I saw her far down the street talking to someone, but I didn’t know who. The dark, the rain—everything was obscured. I approached her cautiously, ducking behind a tree, waiting for the right moment when I could finally go up to her and try to speak again. After another strike of lightning, she was alone at the minibus stop where I’d just come from. I walked over and stood next to her tall, illuminated figure. I just stared, hoping she would recognize me and start up a conversation. She eventually turned toward me, even smiled, and said, ‘Good evening.’ She offered to share her umbrella, so I shifted closer to her. But she didn’t seem to know who I was.”

“You said you last saw her in 1980? That’s a long time ago,” I said.

“Not long enough to forget a friend.” The way Gedeyon twisted his lips with spite made me think this was a man of impossible expectations. “She should have remembered,” he said. “The thing is, she has always been on my mind. I wrapped all this guilt up around Marta, all this significance and longing; so much so that I could recognize her anywhere, even in the middle of a blackout with just a flash of lighting to reveal her face. It never occurred to me that her feelings wouldn’t mirror mine, at least a little.”

“So what did you do then?” I asked, hoping he’d just wished her luck and walked away, but I already knew him well enough to know that he hadn’t. And I couldn’t walk away myself because his story now had a hold on me.

He continued: “I responded to Marta, ‘Good evening to you as well,’ and added, ‘Don’t I know you?’ I thought that maybe she just hadn’t given me a proper look yet, but when she turned and looked me up and down with that judgment-filled face, she said, ‘No, I do not believe we have met.’

“We began to talk. I didn’t say much, just listened. She said she was going to stop by church to give thanks for how life had turned around for her. I realized this was my opportunity to ask about her life—maybe she would have a flash of recollection then. She told me some general details. She said there was a time she’d been in prison during the Derg, but that was then. I told her I had been thrown in prison too, by mistake, and she said, ‘What a shame.’ She leaned a little closer to me, so I got the courage to ask why she’d been arrested, and she deflected, saying, ‘Oh, I don’t remember, and besides, does it even matter?’ ‘Of course it matters,’ I said. ‘Oh, I don’t know,’ she replied. ‘They’d target you for the most absurd things.’ She shrugged as if she didn’t want to give it much thought. I imagined exactly what they must have said to her anyway. They’d accused her of being a bourgeois princess, more interested in the state of her closet than the very state in which she lived, skipping rallies to do her hair and dodging speeches to read fashion magazines. That’s what they might have said to her because that’s what I’d told them. That she was a nonbeliever, a threat to the cause. Those were the words I’d used to trade her freedom for my own. It had to be done.”

I didn’t know what to say to that.

“I’m sure you’d rather not be here.” He stared at me with despair. “You left and avoided these difficult truths. You haven’t had to see the heavy weight some of us carry around. Do you think I’m ashamed of having survived the way I did? Why should I be?”

I didn’t defend myself; what had I done?

“I never said I’m a good man,” he went on. “I was just a regular man, but the Derg, it made me … it made me and it unmade me. It took a regular man and then heightened my worst instincts. It gave me the permission to be worse than I was ever meant to be or would have been in another place, another time. It gave my sins a platform, gave them cover, gave them cause. And for whatever reason I still can’t explain, I took the Derg up on this opportunity to abandon my good senses and do as I pleased. I believe—really believe—there was good in me once. I guess I don’t know that for sure, but I think it’s true. I think I was decent once. I could have been a regular kind of man. Maybe I didn’t have the courage to be better, or didn’t have the luxury to be better. I couldn’t avoid the hard choices. I was here, made here, unmade here.”

He clasped my hand and held it closer, and the warmth of his breath on my skin began to repulse me. Why did I feel like I owed this stranger something? He seemed frail, and despite his bitterness toward me, I felt like he needed me. I felt his forehead again, which was a bit hot. He put his cheek to my hand, pursing his dry lips.

“So the rain was just pouring down now, and the cars were whizzing by loudly, and Marta was almost shouting, telling me she’d not only survived the experience of prison, but that it also made her more self-reliant and tough. As awful as prison was, she had to invent ways to endure what she thought would be unbearable, what she thought would break her. She said she struggled but eventually created a space to be calm within herself. Gradually she was able to create a space to let joy enter her life as well, even there in prison—they were the most fleeting moments, but they were something. She found a way to make those fleeting moments last. She found a way to forget, which was the hardest accomplishment of her life. And when she learned how to do that, she found a way toward purpose. She hadn’t cared about school before because she hadn’t cared about much, she said. But she made a choice to get educated, and she was able to do it. The Derg loved to throw intellectuals in jail—the students, the professors, the writers—and the prisons during the Derg were the best schools in the country, as some say. Marta also met her husband there, and when they were both released or escaped or otherwise got free, they fled together to America, swept up in that wave of refugees, and landed safely on a shore called New England where they went back to school and started a family. She got a good job and didn’t look back on that time except to acknowledge that she was lucky in the end.”

Gedeyon stopped to catch his breath, and I said, “Well that’s about as good an outcome as you could hope for.”

“You could say that.” He pressed his head to my hand once more. I could feel his fever now. He told me that he’d forgiven himself for the wrongs of the Derg, and damn anyone who judged him for that. “Damn you too, if you’re judging,” he said. But he hadn’t found a way to forgive himself for his other sins, and I saw then that he was making me his confessor.

“Is there someone I can take you to talk to?” I asked him.

“Would you rather me tell this to a friend? A friend who I want to respect and remember me well? Or tell my priest, who I have known all my life and who I respect? My family, who will carry forth my name? My colleagues in whose esteem I hope to remain? Would you rather me call it out from the rooftops and confess to the city? … Or should I tell a stranger visiting from halfway across the world who looks like she doesn’t make the return trip all that often? And who has managed to be a child of the Derg without carrying the same load, but who should shoulder it as well?”

And he paused, and I saw the evidence I’d been searching for all along, an empty bottle of pills falling from his pocket, and I couldn’t tell if these had been to help him or if they were what made him sick. I couldn’t even tell if he’d taken them.

When I asked him, he just said, “Listen, child, to my last words.”

What could I do but hear him out and share the burden of his secret now? I knew if I said nothing, he’d continue, and he did.

“I asked Marta, ‘What was it like, being a refugee?’ ‘It’s not for the faint of heart,’ she said, sweeping her short curly hair off her face with her left hand. The strands caught the light and shined, and I thought I’d never seen her look so sophisticated, so strong, so completely out of reach. I was drawn to her, so I pulled in a little closer to listen.

“She told me, ‘Not even my mother knew where I’d gone when I fled Ethiopia, not at first, but eventually I was able to send a letter, and then we corresponded as much as we could. When my family finally saw me after thirty-five years, they told me how good I looked for someone who’d come back from the dead.’

“I was gazing at Marta, clenching my fist so tight I felt my fingernails bending back, so I put my hands in my pockets and looked at the beams coming off the car headlights, circling her like she was encased in jewels, her body haloed by the glow of the streetlight behind her. She is still something, I thought. Not just someone who has reclaimed what’s lost, but someone somehow ennobled by loss. I don’t know how to explain this, but I looked at her like she was either my proudest creation or my most wretched punishment. I don’t exactly know what I felt, but with false pride I told Marta about my own life, the basics: I was a chemistry and math professor, had a wife once, but it didn’t last long. No children, my family mostly gone. I lived freely. Mine was what I called a content and unencumbered existence with routines, stability, and modest comforts, which was more than I’d been born with, and so I felt successful, for what was success if not to die with more than what you had coming into the world?

“Marta said I must be proud of all I was able to accomplish despite my time in prison. She added, ‘Sometimes, things even out in the end. Karma, justice, and all of that.’ ‘Like an equation,’ I replied. ‘That we’re always balancing.’

“She said something I couldn’t hear over the rain, so I stepped a little closer, and when she craned her head to see if the minibus was on its way, I fixated again on the light glistening off her hair. I reached out to her by instinct. A car sped by and honked and I pulled myself back, which sent her umbrella out into the darkness, as if a strong gust of wind had caught it. Marta lost her step. She slipped on the muddy curb and fell onto the street, her ankle stuck in the gutter.

“She reached out, and I leaned toward her. She needed me—for once. So I reached for her, my hand nearly touching hers, and Marta whispered, ‘Kind stranger.’

“And I froze, because even now, especially now, the Marta of my dreams and nightmares and fantasies, haunting Marta who had scolded me for wearing those old shoes, who had failed to recognize my achievement getting the new pair, who had talked to me for half an hour that very night and still had no idea who I was, now called me a stranger.

“I realized then, as she held her hand out to me, that she hadn’t even introduced herself that night, hadn’t told me her name, nor asked for mine. I was a stranger and always would be to her. I was frozen and the cars honked their horns, unable to stop, the beams of the headlights closing in, overtaking her, and she lunged desperately for my hand, almost a helping hand, almost a friend.

“When the ambulance came, there was really nothing left to do. I knew I could say with some degree of honesty that it had been an accident—a horn, the umbrella, Marta stumbling, me somehow not being able to get to her in time. I try to make sense of that moment. I thought it was my chance to leave the past behind. But that was not the way, was it?”

He was posing a question, but not to me, whose name he’d never asked, a stranger who was there for him in his moment of need, something he didn’t seem to recognize.

“Tell me what you think of my story,” he said, and I didn’t speak, didn’t move as he leaned forward and rubbed the dirt off his shoes, caring for them like they were his salvation.