Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: IVP

- Kategorie: Religion und Spiritualität

- Sprache: Englisch

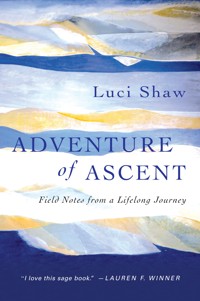

In this book, writer-poet Luci Shaw has given us a lifetime of exquisite reflections on nature, love, death, suffering, loss, faith, doubt, creativity, curiosity, lifelong learning—all of it drawn from the breadth of her own experience, harvested in penetrating and lyrical insights. Still active in her eighties, Luci now turns her attention to the season of edging toward the borders. Her spirit of adventure, her brave transparency, and her openness to all that life offers (as well as inflicts) makes her a captivating and hope-inspiring mentor.For most of us, growing older is a reality we put off as long as possible—until we realize with a shock that it is happening to us. We immediately look around to see how others on the path just ahead of us are dealing with it. So here is the intrepid Luci Shaw, taking readers on a virtual hike with her, with steps more deliberate and slow but also with surprising vistas that fill us with gratitude.In this book Luci serves as a fearless and eloquent scout. As she traverses new territory, she records her experiences lovingly, honestly, sorrowfully, joyfully—here's what it's like, and here's what to be ready for. These field notes will inform your own journey, no matter what your age.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 230

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Luci Shaw

Adventure of Ascent

Field Notes from a Lifelong Journey

InterVarsity Press P.O. Box 1400, Downers Grove, IL 60515-1426 World Wide Web: www.ivpress.com Email: [email protected]

©2014 by Luci Shaw

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from InterVarsity Press.

InterVarsity Press® is the book-publishing division of InterVarsity Christian Fellowship/USA®, a movement of students and faculty active on campus at hundreds of universities, colleges and schools of nursing in the United States of America, and a member movement of the International Fellowship of Evangelical Students. For information about local and regional activities, write Public Relations Dept., InterVarsity Christian Fellowship/USA, 6400 Schroeder Rd., P.O. Box 7895, Madison, WI 53707-7895, or visit the IVCF website at www.intervarsity.org.

Scripture quotations, unless otherwise noted, are from the New Revised Standard Version of the Bible, copyright 1989 by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the USA. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

While all stories in this book are true, some names and identifying information in this book have been changed to protect the privacy of the individuals involved.

Cover design: Cindy Kiple Image: Cut Bank-Sea Landscape by Clare Froy, UCL Art Museum, University College London

ISBN 978-0-8308-7188-9 (digital) ISBN 978-0-8308-4310-7 (print)

Dedicated to those who have already summited

Contents

Acknowledgments

A Word to My Readers

1 The View from Here

2 Looking Ahead

3 Feasting on Distances

4 Fit for the Climb?

5 Dangers Ahead?

6 Finding Sure Footing

7 Bivouacking

8 Above the Tree Line

9 Learning to Breathe

10 The View from the Slope

11 Lightening the Load

12 Liftoff!

13 Mountain Pilgrimage

14 Incidents and Accidents

15 Course Corrections

16 Companions on the Way

17 The Grass Under Our Feet

18 Experiencing Altitude

Notes

Praise for Adventure of Ascent

About the Author

IVP Crescendo

More Titles from InterVarsity Press

Acknowledgments

That this book, born and reborn multiple times with different intentions and formats, has finally reached publication seems quite miraculous to me. Originally it was written to cover the seasons of the calendar year and the church year; later it was torn apart to reflect a metaphor—the stages of aging viewed as a mountain-climbing expedition. Writing the book became an adventure in itself!

Along the way I owe more than I can adequately say in gratitude for helpers more far-sighted than I, who was no longer able to look objectively at what I had written. Mary Kenagy Mitchell read an early draft of the book and gave me many insightful comments. Lauren Winner read it through in one evening and sent me a blurb on the spot. Lil Copan deserves the highest plaudits, clarifying, refocusing, slogging along with me through the text to make the book hold together. Patience, loving perseverance and skill are her other names, and I love her for how she helped this book to evolve and kept me from gloom and blockage. My brilliant agent Kathy Helmers took me on enthusiastically when Lee Hough, my other gifted literary agent, had to bow out due to grave illness. Lee had responded with such enthusiasm to the idea of the book. Later Kathy’s wide experience and thoroughness brought the project to the attention of Cindy Bunch at InterVarsity Press, where I feel like a member of a family. I’ve known Cindy’s professionalism and enthusiasm over the years and feel secure in her hands. Gratitude as well to Ruth Goring for her perceptive and thorough reading and copyediting.

At an early stage I read parts of the manuscript to a couple of church groups. I also fed it in bits to members of the Chrysostom Society. I got such great feedback from these other women and men about my accounts of getting older, with its challenges and opportunities, that I was encouraged to keep writing.

Profound thanks also to my family tribe for sustaining me through this labor, encouraging the book to be born and grow. They are all part of the story—Robin, Marian, John, Jeffrey and Kristin. My husband, John, ever an optimistic and encouraging presence, has hovered in the background of everything I do; I could not have finished this book without him.

A Word to My Readers

The climb of my life offered to you in this story has been both arduous and thrilling. As I’ve hiked this long slope of living, there have been crevasses to avoid or scramble out of, and mountain paths that wind high and low through immense evergreen forests. I’ve stumbled often, have fallen, been bruised and abraded. I’ve had to avoid sharp rock outcroppings and endured earth tremors as well as being awestruck by magnificent views of heaven and earth.

I remember how, from a mountain peak, Moses’ mind was marked with a vision of the Promised Land for his wilderness-wandering people. And how though he never entered it for himself, he gave them hope for their future. I have no certain vision for the future beyond desires and longings; I have some regrets but also great gratefulness. I can look back and see how my trajectory flung a banner across the foothills.

I often wish that my life had unspooled neatly inch by inch across this varied landscape, like a thread that can be examined for flaws and tangles and shrinkage as it unwinds. But since it cannot be rewound, I have to rely on memory and experience and physical evidence—photos and journal entries and letters—to tell you some of what these recent years are like.

I want to describe to you my journey, in what ways it is unique, just as yours is. I want to convey to you how morning and evening light differ, how the lungs and leg muscles ache as they climb, searching for footholds, often resting to take in the view over a pleat of the gradient.

I want to describe how good it is, sometimes, to simply let grass grow under my feet or feel the sun rest on my shoulder blades, or to pick a few berries from the bushes, or to watch the sun rise and set and rise again.

It has been, it is, a great adventure, this expedition we call human existence, though it is not always one that we might have chosen. It’s a partnership, really, between the One who gives each of us life to start with and what we do with that incomparable gift.

Often, shadows like storm clouds have shielded the sun, or a thick mist has disoriented me. Snow squalls and a biting wind often pick up, and then I huddle with other climbers, refugees in small shelters like mountaineers in alpine huts during a blizzard.

Just as the sun is often hidden behind clouds, God’s face has often seemed to be obscured, and then, when I feel most alone in my human frailty, I feel abandoned and vulnerable. I’ve learned a lot about waiting, and longing, for the light to return, for travel fatigue to fade as energy seeps into my bones again.

I plan to tell you about my frequent need to stop and check and find my bearings again, as if with a spiritual GPS. I surmise that there are no straight lines to the top, no mile markers to tell me when I might summit this mountain. When the peak is outlined cleanly against a glowing sky it looks attainable, even welcoming, but I know that such views can be deceptive; it may be a false summit with the real one much farther away than I can see. Warning signs about avalanches or steep declivities show up and cause anxiety for all of us on this trek.

This is a story with many stops and starts. Some questions with no immediate answers. Doubts that weigh heavily and are not easily resolved. Many admissions of failure. High hopes and purposes as well as detours and uncertainties. And triumphs and revelations that sometimes overwhelm my astonished soul.

Yes, this has been a magnificent adventure. I invite you to come and view it with me!

1

The View from Here

I see us wherever I go. The ones who are old enough to be full of the accumulated wisdom and insight of a rich lifetime. The ones whose faces still betray a certain confidence and fortitude. The ones who continue to have optimism about the future of the human race, and hope still to contribute to it. And the ones who have gone blank; who are saying to themselves, What’s the use? (Though that’s not a question; it’s more a statement of reality.) These are the ones who don’t have the energy to care anymore. It makes me wonder: is there a difference between acceptance (It is what it is. Live with it) and passivity (I just can’t be bothered anymore)?

We are an aging population, and we crowd the malls and the churches and the supermarkets and airports and streets. We look for elevators instead of stairways. We get around in wheelchairs, or scooter chairs, or the special carts the supermarkets provide for the disabled (after surgery I’ve used them, and they work well enough, allowing some mobility for the ordinaries of living). If we can still pass our driving test and take to the road, we drive a bit more cautiously and hang our blue-and-white handicapped placard from our rearview mirror to claim the reserved spaces in the parking lot. There seem to be more and more such spaces allotted for our use. For them, too, I am grateful.

I’ve learned to take my placard with me when I travel, so that if I rent a car in some other city I can use it. I watch for those special parking spots with their blue-and-white signs. They mean that I won’t have to walk so far to get to some entrance, some destination.

We are bent and slow, and our gait is often constricted by pain. We get the AARP bulletin in the mail that gives us advice about how to perk up our sex life and deal with the social security crisis. Though demographics show that we are achieving political power, weakness, slowness and caution have begun to characterize our movements. We plod. You could call our speed deliberate, because we almost have to deliberate before mounting the next step. Some of us are accompanied on our grocery outings—perhaps a younger woman, a graying spouse, an equally frail friend, or just our own cane as a companion.

Our expressions vary; some have a grin for anyone who greets them; some project enthusiasm and optimism; some faces are drawn with effort and ache. The expressions of some seem to define what loneliness looks like. A kind of interior resignation etches many features. From the language of the body I translate it as What else can I do? We keep going. It’s our only option.

Like the smoke that pollutes the sky somewhere

I’m a dream that dissolves in endless air.

So why should I care that I’m losing my hair?

When I see this kind of shriveling in another human being, I automatically straighten up, walk taller and try to pull in my stomach. It’s a sign to myself that I haven’t given up yet. My mother had a thing about good posture, and I was well-trained, made to walk around the house balancing a book on my head, which requires a truly vertical spine. Mother lived to ninety-nine, though against her iron will arthritis eventually curled her into a human comma.

I used to be proud of myself that I could run up and down a flight of stairs. My father raced, two steps at a time, up any staircase he encountered around the world until he was over eighty. Perhaps for both of us it was a kind of showing off, a bravado, a way of defying the odds, of proving that disability hadn’t caught up with us. Yet. I’m still in a house with stairs. I take a nap in the afternoon. My study is on the ground floor, but having our bedroom upstairs means I must make several climbs a day to the second floor. I tell myself it keeps me mobile.

It hurts a lot, especially my left knee, which has only recently been “replaced” like its right counterpart. It doesn’t want to bend much, so it hurts even more coming down the stairs, even though gravity is on my side. Tylenol for Arthritis is my constant friend.

But it was Emerson who said: “People do not grow old. When they cease to grow they become old.”

So there’s a goal I’m aiming for. To keep growing, even as the number of years add up, and up. And in this book I hope to act as a scout moving into new territory and reporting back to the coming generation so that you may know what it’s like, and what to be ready for.

The Door, the Window

To get older is to watch the door close inch by inch

against my will so that the inflow of silky air

stops, and the creek’s subtleties of sound.

In the small house of my ear I listen closely to

the message of blood, knowing others are deaf to it,

as I begin to be to their soft speech across

the dinner table. My memory thins; names drift

just beyond the rim of recollection. I’m told

the floaters in my right eye are only gel thickening

into dark splinters that diminish the light.

“Nothing can be done,” my doctor says. “You’ll

get used to them.” I am not getting used to them.

My years undermine me, eating away in the dark,

silent as carpenter ants in the beams. The pine mirror

in the bathroom reflects my white slackness; why

are my cells failing me just when I am

getting the hang of their glistening life? The minutes

wear me away—a transparent bar of glycerin soap,

a curved amber lozenge dissolving

in daily basins of water. The window glass, brittle

as the scalloped collars of ice that shrink our stream,

still opens its icon eye to me, allows me to see

across the sun-struck grass, white with frost, to hear

the water telling its winter story, telling mine.1

Then I remember the tale of Bilbo Baggins: “‘Go back?’ he thought. ‘No good at all! Go sideways? Impossible! Go forward? Only thing to do! On we go!’”

At the outset I must let you know my purpose for this chronicle. I plan to document my life as it moves toward the summit. I don’t know what lies ahead, but I’m committing myself to noting things that seem worthwhile or significant. To report on reflections, insights, new news and old news, in the hope that I may shed a clean light on what it’s like to be edging, inevitably, toward . . . ?

This onward movement is inexorable. Almost every week now I get news of colleagues and contemporaries who have left us. I’m getting used to the word die and would rather use it than the euphemisms “give up the ghost,” “pass away,” “pass on” or simply “pass.” Deceased is a terribly technical word for me—impersonal, what a coroner might say about a body discovered after an accident. Some Christians talk about their family members “going home,” but I wonder if the strange new atmosphere of heaven will feel homelike. Dying is an unshrinking reality that can’t be euphemized with any authenticity except by those who are already dead and who, because the lines of communication have been severed, cannot tell us what it was like. I want to cut to the bone about this business of being old and getting older. So you’ll know and understand. So you’ll know and not fear.

In this telling I vow to be scrupulously honest about myself and the events in my life. I will not fudge about my flaws or attainments. I will try to be compassionate about the failings of others and celebrate their triumphs.

If aging is a disease, its name is senescence. There’s a well-developed branch of medicine to deal with it, gerontology. It’s all well and good to name this condition and refer to it in textbooks. Living it, living with it, gives it a face and an array of recognizable symptoms.

The trouble with aging is that there’s really no remedy. In the end, no one survives it.

Unless they themselves have some kind of fatal disease, young people rarely feel the threat of death or diminishment. They expect to keep going forever. For youth, the fires of energy flow through them and feel inextinguishable. Young people expect to climb the mountains of possibility with a vitality that slowly begins to ebb, I’m told, in their thirties, though when I was thirty such a thought hadn’t entered my mind (I was too busy with four children and a new business to run with my husband). In early adulthood I was, as Sarah Payne Stuart describes it, “still radiant with the delusions that brighten the threshold of middle age.”2 Gradually it becomes apparent to all of us that eternal youth is a myth, except for minds alive to possibility, or perhaps fantasy.

Of course, for authenticity, I’m writing as a woman. But my male counterparts may be asking similar questions, searching for meaning as I do. They also experience comparable physical deterioration, with some minimal differences. They may have prostate problems or erectile dysfunction, and they tend to lose more hair, while I am liable to pee from sudden sneezing or laughing too hard (I do a lot of laughing and I have an overdeveloped sense of irony), and I worry about osteoporosis. A recent bone-density test revealed that I have ostopoenia, a dwindling of bone mass, though I’ve taken calcium and vitamin D3 scrupulously for years.

Both genders dread the loss of independence and the onset of dementia, conditions that loom like the sickle of the black-robed Grim Reaper over our purposes and plans. I recently learned of a brilliant friend’s bereavement after her husband’s death from stroke. She is a good bit younger than I and she has dementia, and now, without a family caregiver, she must join the ranks of others in a home for Alzheimer’s patients. It is grievous to see what can happen to such a vigorous human mind.

Jeanne Walker sent me a new poem today. Her unique singing voice comes through so clearly. She picks up on details but pulls them together with other seemingly unrelated details to form a new dynamic whole. One image she used described her “fiasco” of a lawn, and the daffodils that “clamber up like miners / still bravely shining their yellow headlamps.” I wrote back to her about that description—how I loved it—but in my letter I typed in “dandelions” instead of “daffodils.” I guess the color golden yellow was what had stayed with me, and my mind did the floral transposition unawares, until I saw it later and wondered if this might happen more and more frequently, with the little gray cells slipping away and making the wrong neural connections.

My tracking of my own personal deterioration, as I describe it, as it happens, may feel self-absorbed to you, even self-serving, but I am the only human being who really knows what’s going on for me. Self-examination is often suspect, because we can’t see ourselves with total objectivity—I know I cannot. But as I live and watch and write my record, I’m hoping for a kind of confessional honesty and transparency that will be essential if this document is to have value for me or anyone else. The transitions may be abrupt, unexpected, with surprising shifts and stops and starts, the way life is—every day different, like the weather in western Washington where I live.

I’m beginning to reflect on mortality, and the aging of mind and spirit that often precedes it—that universal end for which the scientists have, as yet, no answer, no solution. I will ask a succession of whys (why do we have to die? in fact, why were we born, why are we here at all?) and whens and wheres (both unanswerable) and hows (sudden death by accident or illness, or a slow kind of desiccation until all our vital juices are drained?). These are not new questions for the human race, but I’m asking them because they are my questions and I long for personal answers. Maybe you can profit from thinking about them as well.

2

Looking Ahead

No matter at what stage of our journey, for each of us the inevitability of dying is always there, like the blank wall of an impenetrable fortress. Or an unexplored planet. Or a looming cliff face before us, with few visible toeholds.

The biblical prophets and teachers have claimed and proclaimed a certain knowledge of what lies beyond that impregnable barrier—a state of being either beatific or horrific. But where are the witnesses? A few have come back through some miraculous orifice in the rampart, but either we have no record of their comments (Lazarus) or they’ve been unable to describe in recognizable terms what they’ve seen and heard. Jesus was resurrected, having “harrowed hell,” but what did that mean?

Many near-death experiences with visions of light or music or voices are documented. But since no one else can see or hear what’s going on in that mysterious interim, we wonder—are these chemical or neurological reactions to the shutting down of our faculties? Is it a dreamlike state of wish fulfillment? Or is this a fore-view of heaven?

My guess is that what lies ahead is indescribable in human terms; that descriptions of heaven (or hell), as in Dante or Milton, are metaphorical attempts to translate a vision that came and went. Like the descriptions in the Revelation of a sea of glass and gates of pearl, and a river of life with leafy trees along its banks, and an open manuscript with lists of names of heavenly residents on it, and some sort of dwellings. (Will we need houses for privacy, or for shelter from celestial weather? I wonder if Jesus talked about the “many residences” being prepared for us to give us a sense of the reality and space of the heavenly community, along with some sort of continuity and familiarity that might be comforting.) But I wonder, will I like the decor, and will I get used to the other amenities? Is there a heavenly version of Scrabble with little ivory tiles and English letters? Myself, I’m hoping for an airy work space with lots of light and books and some flowering potted plants. And a PC that never gets obsolete.

Yet here’s what Emily Dickinson, from her secluded nook in Amherst, suggested: “For Heaven is a different thing, / Conjectured, and waked sudden in— / And might extinguish me!”1

Andrew Hudgins surmises something far less overwhelming about those who look forward to living in heaven: “They’ll talk of how they’ll finally learn to play the flute / and speak good French. // Still others know they’ll rot / and their flesh turn to earth, which will become / live oaks, spreading their leaves in August light.”2

So for now we must do with hints and guesses—a collage of human hopes and dreams and uncertainties. We are left with a provisional present that is winding down like a loosened spring. That loosening is what I hope to describe, as long as I have any powers of description left.

3

Feasting on Distances

I’m writing about the process of getting older, with the difficulties and deficits of age. I’m eighty-four, definitely on the uphill side, yet I’m so very glad I’m alive!

Reading Amy Frykholm’s recent “contemplative biography” of Julian of Norwich, I came across this nugget from Julian’s own writings: “God is being and wants us to sit, dwell and ground ourself [sic] in this knowledge while at the same time realizing that we are noble, excellent, assessed as precious and valuable and have been given creation for our enjoyment because we are loved.”1

This is manifestly so for me, as on a clear day with the smell of frost in the air, when I feel exhilarated. The multiple tones of the color green do it for me. And all the other colors, and the textures and smells and sounds that bring my senses to full alert.

The arrival of a new idea or image for a poem propels me into such a fervor that my body tingles along with my mind. So much is wrong with the world, but so much of it is right, particularly the parts that seem to have spilled directly from the Creator’s hand! What are the chances that when I was born I would turn out to be me, to have the astonishing chances and choices I’ve had? Beauty, in any form or color, makes me sing and have hope. Can I ever be thankful enough?

Though the struggles of living and survival have sometimes seemed unbearable, I’ve not been an unhappy woman. Growth and experience and the richness of creation have often brought me an intense joy in living. My five children and their own lively and intelligent offspring, and now my great-grandchildren, each such a distinct and gifted individual, have brought me all the joys and trials of parenting—a fullness of experience that I have never regretted. Matriarchy can be fun! Having had two faithful and supportive husbands in succession, men who put up with my ups and downs and always gave me the benefit of the doubt—how grateful I am for them! And my friends of the heart—my longtime camping/writing/knitting companion Karen, the prayer partners, Lydia, Marya, Claudia, Deb, Jennie, Bev, who meet in my study Monday mornings, all the fellow writers and artists whose helpful encouragement and critique have blessed me over the years—where would I have been without them?

What frees me most completely from the hindrances of physical disability is driving! My reflexes are still quick and reliable. My eyes are good enough. I hear well, except at a table with lots of other talkers all trying to make themselves heard. I’m a good and seasoned driver and I love cars. As the new models are introduced year by year, I learn to identify them and enjoy their sleek designs with excitement. I’ve had a love affair with automobiles, the movable domains for travel, ever since I bought my first Honda Accord after the death of Harold, my first husband and the father of my children. The car was a gently-used model, and my son Jeff helped me to find the auto dealership in downtown Chicago. The car had a stick shift, and I loved getting what was called “the feel of the road.” Since then I’ve had a string of Toyotas, Subarus, more Hondas and one small diesel-powered Nissan. I love the little pearly-green Prius I have now and feel noble and happy that its reduced emissions are not contributing too much to climate change.

Long distances are my joy—from Bellingham to California and back, camping along the way, relishing the sense that the hills and the green valleys and the lion-colored deserts of the continent are unrolling beneath my wheels hour after hour.

If I had the money, I’d get a canary-colored Ferrari with a gigantic spoiler. I’d own the road!