After Zionism E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Saqi Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

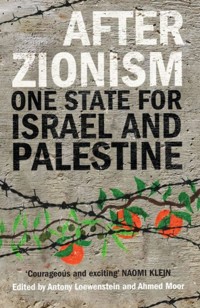

'Nothing will change until we are capable of imagining a radically different future.' --Naomi Klein After Zionism brings together some of the world's leading thinkers on the Middle East question. In thought-provoking essays, the contributors dissect the century-long conflict between Zionism and the Palestinians, and explore possible forms of a one-state solution in the most conflicted part of the world. Time has run out for the two-state solution because of the unending and permanent Israeli colonisation of Palestinian land. The Hamas attacks of 7 October 2023 and Israel's subsequent devastation of Gaza have given renewed urgency to the discussion of how to move towards a future that honours the rights of all who live in Palestine and Israel. This timely edition includes a new preface as well as challenging and insightful essays by Omar Barghouti, Jonathan Cook, Joseph Dana, Jeremiah Haber, Jeff Halper, Ghada Karmi, Saree Makdisi, John Mearsheimer, Ilan Pappe, Sara Roy and Phil Weiss.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 437

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

AFTER ZIONISM

ANTONY LOEWENSTEIN is an independent journalist, author, filmmaker and co-founder of Declassified Australia. He has written for The Guardian, New York Times and New York Review of Books. He is the author of the bestselling book, The Palestine Laboratory: How Israel Exports the Technology of Occupation Around the World, which won the 2023 Walkley Book Award. His other books include Pills, Powder and Smoke, Disaster Capitalism and My Israel Question. He was based in East Jerusalem between 2016 and 2020.

Ahmed Moor is a Palestinian American writer and activist. He received a Masters in Public Policy from Harvard as well as a Soros Fellowship, and has written for the Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, London Review of Books, Guardian and Al Jazeera English. He is the founder and was formerly the CEO of an emerging markets lender based in Amman, Jordan. He now resides in Philadelphia where he is an elected Committee Person in the Democratic Party.

“Nothing will change until we are capable of imagining a radically different future. By bringing together many of the clearest and most ethical thinkers about the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, this book gives us the intellectual tools we need to do just that. Courageous and exciting.” Naomi Klein

“This book is nothing if not thought-provoking, in the best sense of the phrase … After Zionism is an uncompromising book which boldly relinquishes nationalism in favour of human rights as an organising paradigm … these essays point the way to a possibly rewarding and perhaps inevitable new direction for the Palestinian struggle.” Ceasefire Magazine

‘Important and timely … a significant contribution to the literature on the one-state/two-state debate.’ Electronic Intifada“After Zionism is rich in history and context, pointing to many failures in the past or attempts at two-state solutions that form a convincing argument for its abandonment.” Middle East Monitor

“After Zionism provides a stimulating and much needed critique of the present reality in the Holy Land.” Washington Report on Middle Eastern Affairs

‘At a time when Israeli society has shifted increasingly to the right and narrowed the acceptable limits of conversation, this volume offers valuable contributions to a debate that should be front and center, yet is confined to ever-smaller margins.’ Publishers Weekly

“Timely and readable …. New thinking is needed to climb out of the stultifying box erected by years of meaningless ‘peace’ negotiations … This book will hopefully spark a broader debate.” Jordan Times

To our parents,and the Palestinians and Israelis who deserve better

SAQI BOOKS

Gable House, 18-24 Turnham Green Terrace

London W4 1QP

www.saqibooks.com

First published in 2013 by Saqi Books

This edition published 2024

Copyright © Antony Loewenstein and Ahmed Moor 2013 and 2024

Copyright for individual texts rests with the authors

Antony Loewenstein and Ahmed Moor have asserted their right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the authors of this work.

All rights reserved.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

ISBN 978-0-86356-941-8

eISBN 978-0-86356-739-1

A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library.

Printed and bound by Clays Ltd, Elcograf, S.p.A

Contents

Preface to the New Edition

Introduction

1. Presence, Memory and Denial

Ahmed Moor

2. The State of Denial:The Nakba in the Israeli Zionist Landscape

Ilan Pappe

3. Reconfiguring Palestine: A Way Forward?

Sara Roy

4. The Power of Narrative:Reimagining the Palestinian Struggle

Saree Makdisi

5. Protest and Privilege

Joseph Dana

6. Beyond Regional Peace to Global Reality

Jeff Halper

7. The Future of Palestine:Righteous Jews vs. the New Afrikaners

John J. Mearsheimer

8. Israel’s Liberal Myths

Jonathan Cook

9. The Contract

Phil Weiss

10. Zionist Media Myths Unveiling

Antony Loewenstein

11. A Secular Democratic State in Historic Palestine:Self-Determination through Ethical Decolonisation

Omar Barghouti

12. How Feasible is the One-State Solution?

Ghada Karmi

13. Zionism After Israel

Jeremiah Haber

About the Contributors

Notes

Acknowledgements

Index

Preface to the New Edition

We write this as bombs continue to fall on Gaza, obliterating families and hopes. Achieving true equality and justice for all Israelis and Palestinians is now more urgent than ever. This book presents a realistic alternative to the two-state fiction presented in the White House and the opinion pages of Western media. Clinging onto failed myths about two separate states is a grave disservice to the millions of people in the Middle East who deserve hope that a democratic nation for all is possible.

Some will accuse one-state advocates as unrealistic, dangerous dreamers at a time when Israelis and Palestinians are at war. But it’s precisely because we’re in this precarious moment that we believe discussing one-state options is so crucial.

The ideology of separatism favoured by the Israeli state – caging millions of Palestinians behind high walls, underground barriers and mass surveillance and under the constant watch of military drones – has failed. It is only through cooperation, sharing resources and addressing historical and present grievances that peace can be achieved.

Ten years ago, when we first published this collection, we believed that the prospects for a two-state outcome to the Israel/Palestine conflict had expired. The basic idea, separation of two people in a small place, a country the size of New Jersey, was a non-starter. In 2009, more than 500,000 Jewish settlers occupied the West Bank and East Jerusalem. Today, that number stands at roughly 750,000 people – a 40 percent increase in just fourteen years. Practically, their presence is an effective coagulant to the Apartheid status quo. There can be no Palestinian state when Jewish Israelis occupy Palestinians, and when Israeli law – which is paramount in the land of Israel/Palestine – extends to Israeli Jews wherever they may live.

While predictions of the future are always fraught and unreliable, it seems reasonable to say that the number of Israeli settlers will continue to grow out of all proportion to natural population growth. In other words, Israel will continue to transfer large numbers of civilians into occupied territory, unopposed by a divided world.

Numbers comprised one pillar of our argument against the twostate paradigm, but the main force of the discussion was moral. As liberals we do not believe that ethnic, religious states are defensible as such. We conceive of political spaces in which voluntary participation is the basic principle underlying citizenship, in which people, in all their individual diversity, are the only currency that counts. An ethnoreligious state, Israel, and an ethnic state, Palestine, do not conform to our view of what a liberal democratic state should be.

So, ten years later we find that our arguments continue to resonate for all the same reasons. Yet much has happened in the intervening period to underline the urgency of the need for change in Israel/Palestine.

During the Obama administration, Washington’s once obsessive focus on the Middle East began to shift as US policy strategically redirected towards China and its ambitious foreign policy. This continued during the Trump administration, but with a new dimension: an effort to “normalise” relations between Israel and the autocratic Arab regimes in the Middle East, which began in 2016.

The Biden administration that came to power in 2021 quickly extended the Trump era “Abraham Accords” – the grandiose name ascribed to the series of economic and security arrangements brokered by the United States, linking a handful of anti-democratic regimes in the region to one another and Israel. Yet the effort to sideline the Palestinians has proven disastrous, as was witnessed on 7 October 2023 when the Palestinian group Hamas killed about 1,200 Israeli civilians and soldiers, and in Israel’s subsequent genocide in Gaza where at the time of writing, more than 20,000 Palestinians have been killed.

And still, despite everything, the two-state outcome has persisted among policymakers, a zombie whose grotesque aspect has only grown with the number of dead in Israel/Palestine. Less than two weeks after the horrific Hamas attack on Israel, US President Joe Biden was in Tel Aviv rehashing old talking points. “We must keep pursuing peace”, he said. “We must keep pursuing a path so that Israel and the Palestinian people can both live safely, in security, in dignity and in peace. For me, that means a two-state solution.”

As if on cue, the European Union Foreign Policy Chief, Josep Borrell, reiterated the same message soon after. “The solution can only be political, centred on two states,” he tweeted. Other Western governments followed suit, speaking as if the Oslo Peace Accords from the early 1990s were a fresh document full of potential, capable of bringing an enduring peace between Israelis and Palestinians.

Seemingly, the White House and its Western allies had missed the rapid expansion of Israeli settlements across the West Bank and East Jerusalem in the last decade and the sharp turn to the far-right of the Israeli public and political establishment. Today, arguments for the forcible transfer of Palestinians into neighbouring states, a repeat of the Nakba, have entered the Israeli mainstream.

Eager not to be outdone, New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman was desperate to join in on the two-state bandwagon.1 In late November 2023, he was writing about the need to “revamp” the corrupt Palestinian Authority to enliven the prospects of the twostate solution because it is the “keystone for creating a stable foundation for the normalisation of relations between Israel and Saudi Arabia and the wider Arab Muslim world.” Friedman acknowledged that two-state advocates, presumably including him, are looking tired and increasingly irrelevant. “These two-staters right now are on the defensive in both communities in their struggle with the one-staters”, he wrote. “Therefore, it is in the highest interest of the United States and all moderates to bring back the two-state alternative.”

We regard the renewed talk of a two-state outcome as a cynical diversion. It’s the “solution” stated ad nauseam when there is no interest in resolving the century-old conflict between Israelis and Palestinians. It’s the “solution” for fewer Israelis and Palestinians than ever before.

Unsurprisingly, the lack of any progress towards peace in the Middle East has negatively impacted the views of Israelis and Palestinians towards the two-state solution. In one Gallup poll, before 7 October, only around one in four Palestinians in East Jerusalem, the West Bank and Gaza supported the idea of a two-state solution.2Backing for two-states has plummeted in the last decade. In 2012, 59 percent of Palestinians had endorsed it.

This collapse was particularly acute for young Palestinians with only one in six between the ages of fifteen and twenty-five supporting it. As 69 percent of the population in the Occupied Territories is under twenty-nine years of age, disillusionment with the two-state solution will only grow. Unsurprisingly, the majority of Palestinians polled had no faith in US President Biden bringing peace either.

Israeli Jews were equally pessimistic about the two-state solution, although their lives were comparatively privileged compared to Palestinians living under occupation. According to a Pew poll released in September 2023, just 35 percent of Israelis thought it was possible “for Israel and an independent Palestinian state to coexist peacefully.”3 This percentage had dropped 15 points since 2013. Arab Israelis were especially despondent, far more than Jewish Israelis, concerning the likelihood of a two-state solution.

Yet it doesn’t follow that Israeli Jews will come around to a single shared state with equal rights for everyone. Indeed, people with privileges have rarely yielded them without some external pressure.

Ten years since the first publication of After Zionism, the need to explain and promote the necessity of the one-state solution has never been more vital. How do we put a stop to endless war and Apartheid? What will it take to achieve justice in Israel/Palestine? How do we secure the future? How do we move beyond Zionism – and what comes after Jewish nationalism?

This collection seeks to grapple with those questions. We are grateful to each writer who has contributed to this book. We are privileged to share their company and have learned much from each of them over the years.

The events of 7 October 2023 and since have shaken us profoundly. Hamas’s ruthless incursion into Israel and slaughter of Israeli civilians were horrific. But this did not happen in a vacuum. Gaza has been an Israeli laboratory for close to twenty years, blockaded and surrounded by electronic fences, drones and surveillance equipment. The majority of Gazans are unable to move freely outside the territory to work, study, live or receive medical care. Hamas may have sought to turn the world’s attention to the plight of the Palestinians, when the world had largely turned away – but their methods were indefensible.

The Israeli retaliation has been devastating. Vast swathes of Gaza are uninhabitable, rendered apocalyptic by relentless Israeli bombing and a merciless ground invasion. Most horrifyingly, Israel has killed more than 7,000 children.

Palestinians are the primary losers in this war between an extremist Israeli government led by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and a Hamas leadership that faces annihilation in Gaza.

The genocidal rhetoric and actions of the Israeli government are having a profound impact on how Americans, Jews and Palestinians view the conflict. The Netanyahu regime has proud and unrepentant homophobes, racists and bigots in its cabinet, spewing bile on a daily basis against Palestinians.

But this is about so much more than one man, Netanyahu, and if he continues as leader. The far-right fringe has entered the Israeli mainstream, normalising the exterminationist mindset. For too many Israelis, Palestinians are second-class citizens simply because they’re not Jewish. Israeli settler-led pogroms, ubiquitous violence against Palestinian civilians and constant house demolitions in the West Bank are all clear signs that Israeli ultranationalists are in charge. These realities have existed for decades, but never on such a disturbing scale.

When we first published this book, the reality of the Israeli occupation was clear to anybody who cared to look. But now, a decade later, there’s been a sea-change in how much of the world views the conflict. Today, every leading Israeli and Palestinian human rights group, along with Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International, have concluded that Israel is committing the crime of Apartheid in the Occupied Territories.

This language, of Israeli Apartheid, has entered the mainstream. That is why in March 2023, more than six months before the Hamas attacks, a Gallup poll found for the first time that a majority of American Democrats had more sympathy for Palestinians than Israelis.4 Eventually and inevitably, endless occupation will incur a political price in the nation that sustains it the most, the United States.

The ubiquity of social media, allowing Palestinians to show the reality of rampaging Israeli soldiers and settlers, often acting in coordination with one another, has undeniably impacted this global awakening. Don’t look away, these Palestinians are telling us: this is the face of Israeli fascism, and it’s backed and defended by almost every Western government.

One encouraging sign – and few exist in the current period – is the surge in public Jewish support for Palestinian rights. US-based groups such as Jewish Voice for Peace and If Not Now? dispense with the once-held fears of speaking out against a Jewish establishment that prioritises Jewish lives and narratives. These Jews back equal rights for all citizens in Israel and Palestine, and eschew Zionism as a militant nationalist movement that cannot provide safety and justice for Jews and Palestinians.

This volume’s co-editor Ahmed Moor was born in Rafah, in the southern Gaza Strip. Like so many others, he has lost family members to the Israeli onslaught since 7 October 2023, deliberate war crimes by the occupying army. The reality of Israel’s war on Palestinians has caused him to question his own conclusion about the possibility of a single state shared by Palestinians and Israelis; the prospect of living alongside Israeli Jews who participated in the genocide is anathema.

Yet, other societies have dealt in atrocity, and from them we draw inspiration. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa is illustrative in this regard. The principles of restorative justice, which seeks to repair the harm done to victims as a first principle, hold, no matter how seemingly unforgivable the crime. The only hope for the living – those who survive the genocide and carry forth their cultural memory and real trauma – is to process what’s been done to them. There will be no recovering the tens of thousands of dead in Gaza, but honouring their memory must mean a future for all the children who survive. This is why we carry on this work.

There is also the question of what Israel’s genocide in Gaza means for Palestinians and Israelis in the diaspora. In the United States, which is the singular contributor to the seventy-five-year conflict, the Democratic party’s embrace of Israel after the events of 7 October was expected. More surprising was the near total failure of the foreign policy establishment in managing the genocide and its consequences.

President Biden in particular demonstrated a total lack of empathy for the Palestinians. By embracing Israel, he demonstrated his unsuitability for the job of the Presidency – he failed to meet the needs of a youthful electorate whose demands for justice flow easily from George Floyd, the African American man murdered by a white police officer in Minneapolis in May 2020, to Gaza.

There is an argument that the president is a figurehead – that his advisors, a suite of informed and thoughtful foreign policy staff, steer the ship of state. But that argument necessarily relies on the balance of the evidence for its coherence. Secretary of State Antony Blinken demonstrated his own lack of judgement when he greeted Benjamin Netanyahu not as the US Secretary of State, but rather as a Jewish man on a personal mission in one of his visits to Israel in October 2023. His lack of restraint resulted in creating greater distance between the United States and its Arab allies and Turkey.

Meanwhile, Jake Sullivan, the president’s National Security Advisor, chose to publish an essay in Foreign Affairs in the week before 7 October designed to demonstrate his command of international strategy. The profound wrongness of a central claim – in so many words, that the Palestinians had been pacified – was made larger by Sullivan’s towering ambition. These failures by the President’s policy staff, and by the president himself, make their claims of a two-state outcome’s desirability even more suspect. Ambition cannot stand in for talent or ability, and slogans and “security arrangements” cannot stand in for justice. It has become clear that the American policy apparatus does not know what to do, nor do the people crafting policy know what they’re doing. The impact of the 7 October attacks and their aftermath will be felt in many arenas, perhaps even in the organisation of the American policy establishment.

Nor are Arab states striving to drive a just outcome to this conflict. The total impotence of Arab leaders, almost all of whom rely on American support in one form or another, means that they are effectively non-entities when it comes to effecting change. Morally, many of them are deeply compromised, holding their own people in stasis through broad, forceful repression.

And so, we return to our theme – one state for two peoples, rooted in justice and in the principles of international humanitarian law. We call for informed analysts and non-specialists alike to begin to continue the effort of discussing and exploring the contours of a single state. Are we talking about a federation of Israel/Palestine, or a consociational democracy – one that prizes community rights above all? The answers to those questions remain for us to grapple with and to answer to the best of our ability.

Equally challenging is the effort to develop a theory of change. How do we go from today – an entrenched Apartheid where Ashkenazi Israeli Jews rest at the top, maintaining a firm hold on the political and economic life of Israel/Palestine, while Palestinians from Gaza, the West Bank and inside Israel, many of them refugees, lay prone, exposed at the bottom of the societal totem?

We believe that the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions movement will continue to carry the force of our argument – the force of justice – forward. And that the emerging global coalition of labour and justice workers, particularly Black Lives Matter activists in the United States, will help carry the work beyond its traditional limits among Palestinians, Arabs, Muslims and anti- or post-Zionist Jews. We cannot talk of hope emerging from the wreckage of Gaza, only a renewed commitment to work for a just future, for everyone.

Antony Loewenstein and Ahmed MoorDecember 2023

Introduction

Antony Loewenstein and Ahmed Moor

The Middle East has changed in profound ways in recent years. The succession of popular uprisings (intifadas), Israeli military operations in the West Bank and Gaza, as well as changes in the political landscape, such as the so-called “Abraham Accords”, have affected everyone in the most conflicted part of our world. However, some institutions remain, from the most right-wing government in Israel’s short history, to the ineffectual and crippled Palestinian Authority.

The Al-Aqsa Intifada marked the end of the 1990s and the Oslo Process before it bled into the twenty-first century, bringing with it widespread cultural and political change for both Palestinians and Israelis. In Israel, society shifted drastically to the Right as the Left disintegrated, and the occupation became more deeply entrenched. The transformation found broad expression in a new consensus: that the Palestinians must be shut out and forgotten. The status quo became permanent.

The settlers in Israel have always had an outsized impact on their society. This partly has to do with the way in which majorities are cobbled together in the Israeli Knesset, but it is also because of deliberate Israeli government policy. Virtually every Palestinian has witnessed the accelerated rate of land theft and growth of illegal settlements in the Gaza Strip and the West Bank on a first-hand basis. The conquest of Palestinian land typically occurs in the presence of an army patrol, acting on official orders, protecting state machinery; there is never anything rogue about what the settlers do.

Until 2005, Jewish fundamentalists in the West Bank and Gaza – who form the ideological core of the settler movement – were contented by the arrangement. It was only when former Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon decided to extract roughly 8,000 of them from the Gaza Strip that the arrangement ceased to be comfortable. It did not matter to the settlers that Sharon was working to buttress their interests by placing the “peace process” in “formaldehyde”.1 All that was relevant was that the state had exhibited a willingness to defy the settler community.

Sharon succeeded. The “peace process” was frozen at the most senior levels of the American government. It was during that period that the second intifada faded from Israeli consciousness and a reasonable standard of security returned to Tel Aviv.

During the past twenty-five years, the average Israeli has become less liberal, less “progressive” and more right-wing, a fact reflected by the election of Benjamin Netanyahu in 2009 and then his startling return to power at the end of 2022, after a series of deadlocked elections. It was a notable failure of the mainstream Left in Israel that the ongoing colonisation continued unopposed – a factor that contributed to the Left’s ultimate dissipation. The general apathy and right-wing malice directed at Palestinians worked to further empower the settlers who had learned the lessons of 2005 well. They worked successfully to place their representatives in high posts in the cabinet and infused the army with their numbers. Today, any move to evict large numbers of settlers from the West Bank would likely be met by mass insubordination. While the takeover of Israel by the settler minority was perhaps unforeseen by Ariel Sharon and David Ben-Gurion, the permanence of the settlement project was not.

Among the Palestinians, the second intifada’s renewed focus on armed resistance and suicide bombings resulted in political isolation and the diminishment of Palestinian society. The violence provided Israel with an opportunity to distract from the fact that its colonisation of the West Bank was proceeding apace. The occupation was endorsed, funded, defended and built with Israeli and foreign money. Tragically, since the Oslo period, the international community has also funded the Palestinian Authority, a body designed to manage the occupation for Israel. It is an arrangement that suits the Zionist state well.

The tragedy deepened for the Palestinians when the man who embodied the struggle – the international symbol of their aspirations – was besieged in his compound by the Israelis for more than two years. Yasser Arafat was deprived of his dignity right up until the weeks preceding his death. His humiliation was something that many Palestinians felt acutely, both at a symbolic level and in their own lives.

Subsequent years brought political divisions between them. The fissure that existed between Fatah and Hamas under Arafat burst into armed conflict after his death. The violence worsened after Hamas won parliamentary elections in 2006. The following year saw the Islamic movement pre-empt a Fatah coup, and with that the Palestinian political body split along geographical lines. Fatah held the West Bank with Israeli and American help, while Hamas continued to govern the Gaza Strip, first with Iranian and Syrian help, then with aid from Qatar, as the Palestinians distanced themselves from the civil war in Syria. Hamas controlled the Strip with an iron fist until its unprecedented attack on 7 October 2023, after which Israel aimed to eradicate its presence entirely from Gaza.

By 2007 it became clearer than ever that any talk of a two-state solution was empty though this hasn’t stopped its advocates in the US, European Union and beyond from continuing to push it at every opportunity. The combined effect of a ravenous colonisation project in the West Bank and deep internal Palestinian divisions both highlighted the reality. At the same time, Palestinian calls for equal rights were gaining in strength; and the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movement appeared to provide an opening for a different kind of resistance to the occupation. BDS has now gone global at universities, businesses and in public debate.

Outside Israel and Palestine, global discussion about the conflict began to shift. Although the mainstream media still sympathised with the Zionist narrative, it wasn’t so uncommon to hear the occasional call for the one-state solution and Palestinian Right of Return. Social media and citizen reporting from the West Bank and Gaza offered the world on-the-ground insights that made it impossible to deny the daily harsh reality for Palestinians.

We – Antony Loewenstein and Ahmed Moor – first began discussing this anthology in the autumn of 2010. Adam Horowitz and Phil Weiss, the editors of the Mondoweiss website, introduced us at a time when so much in Israel and Palestine was changing and connections between people on different continents were quickly deepening thanks to the Internet. Indeed, that is as true today as it was thirteen years ago.

Ahmed is a Palestinian-American who witnessed the disastrous effects of the Israeli occupation firsthand. Antony is an Australian Jew who was brought up expecting to believe in Zionism and the Israeli state, but by his late teens started to question its legitimacy. We come together on this book not because we agree on everything – we don’t – but because of a shared belief that Jews and Palestinians are destined to live and work together, whatever our differences in background, ideals and daily life. We are connected by a desire for justice for our peoples.

To us, it seemed that the conversation about the end of the Oslo process and what may come afterwards was widespread. New sources of web information like Electronic Intifada, Mondoweiss and dissenting Israeli and Palestinian bloggers and tweeters were forcing a fresh openness in the discussion of the facts in Israel/Palestine. More and more people seemed to recognise that the obstacles to the emergence of a Palestinian state were deep, enduring and growing. Despite that, most mainstream media coverage in America and elsewhere continued to talk about a “peace process”, supposedly generous offers by Israel and America to the Palestinian leadership, and ongoing “terrorism” by Palestinians in Gaza and the West Bank. The Barack Obama administration, despite liberal hopes of “Yes, We Can”, became little better than a handmaiden to Israeli demands. Washington’s position changed little during the Trump and Biden eras, entrenching Israeli control over all of Palestine.

We are frustrated with the largely myopic journalism that appears from the West. Palestinians are often portrayed as savages, terrorists or just faceless people. Israelis are the peace-seeking, aggrieved party. Neither stereotype is even remotely true, and the web has cracked this illusion. New and younger voices – such as Palestinian bloggers in Gaza, anti-Zionist Israelis, western peace activists and non-violent Palestinian leaders in the West Bank – are being heard online. They deserve wider coverage.

The decision to compile the essays in this collection was a natural one. These are the conversations that are pertinent today and the issues they raise will continue to be relevant for years to come. There is a diversity of issues and views represented, but in requesting the essays, we asked all of our contributors to keep the one-state solution in mind as they wrote.

The writers are from a wide variety of backgrounds: some from the academic establishment, while others are new media reporters in the West Bank. Some are Jewish, some are Muslim. Palestinians, Israelis and the Diaspora are all represented here. We wanted diversity, not conformity. We don’t agree with everything that appears in the book, but we believe in having the debate. Moving from the discussion over how to achieve the unjust two-state solution – something that still occupies the minds in the White House, much of the corporate media and elements of the Palestinian and Zionist lobbies – to another, more equitable outcome is the challenge we seek to address.

After Zionism is a series of steps along that road, with the necessary twists, turns and contradictions at a time when facts on the ground are finally bringing a realisation that the one-state solution is the best way forward.

The idea that Palestinians and Israelis can share a single country is not a new one, but it was buried and forgotten for a long time. As the two-state outcome has faded from the minds of people who know the region, many are beginning to revisit the idea. In America and elsewhere in the West, the one-state solution is no longer a fringe discussion being conducted at the margins of the political debate.

We are both long-time advocates for a single state solution, but not all the contributors to this book have always agreed. So, part of this process has been about chronicling recent history – what happened, what changed, why can’t we go back to Oslo? A strong emphasis on human rights is a common current throughout this book, but that doesn’t necessarily translate into a common vision. We feel, however, that a wide range of the historical and moral debate is presented within these pages – and that these discussions necessarily inform our view of the future.

After Zionism isn’t a position statement. It is a collection of essays that challenge much of the accepted status quo for the last decades. If the two-state solution will never happen, surely it’s time to try something different, something more just? The obstacles to achieving justice are huge and the critics and cynics are many. But what is the alternative?

In our minds, the one-state solution’s time has surely come.

ONE

Presence, Memory and Denial

Ahmed Moor

I remember the fall of 2003 clearly. I’d just commenced my freshman year at the University of Pennsylvania and like many seventeen-yearolds, I was glad at being newly independent.

The school had undertaken a programme to socialise incoming students. It consisted mostly of ice-cream parties, which did a lot to create a low-stress, adjustment-mode environment. It was after one of these events that I met another freshman in my class. Our conversation carried on normally until the young woman I was speaking with asked: “Where are you from?”

“Palestine,” I said.

She looked at me for a moment before replying, “There’s no such thing.”

The politics of denial is the politics of occlusion and erasure, of negative spaces and dark holes. It is a manic, hysterical and angry politics. It is sometimes the politics of atrocity.

For several weeks in early 2012, members of the Republican presidential line-up tripped, lurched, and tumbled over one another in the frenzied competition to announce their deep love for Israel. Governor Rick Perry of Texas promised that the small Mediterranean state would be the first country he visited as president. Former Massachusetts Governor Mitt Romney insisted that he would confront Iran head on – to spare the Israelis the burden of doing so themselves. And as comedian Jon Stewart humorously pointed out, only Israel could cause Congresswoman Michelle Bachman to boast proudly of her time spent as a labourer on a socialist commune – a kibbutz.

The grim slide from comedy to anguished absurdity accelerated when former Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich sought to mark himself apart. In an interview with a small Jewish cable television network, he made the blandly genocidal statement that the Palestinians were an “invented people”.1 It was an assertion he felt comfortable repeating days later when he evoked Ronald Reagan – a mythical, folklorish figure among Republicans – to underline his “historical” claim. Gingrich’s mendacious statement was not a historical or an anthropological one. It was politics – one with a long history in Palestine.

Zionism, the nineteenth-century European movement to colonise Palestine, has always struggled with an inconveniently inhabited Holy Land. In the minds of Theodor Herzl and David Ben Gurion, the indigenous people – the Palestinians – were a direct obstacle to the redemption of an allegedly effete, bookish European Jew. Labour Zionism – the unlikely admixture of Marxist labour principles and ethnic nationalism – emphasised the role of the land in the Jewish man’s “redemption”. In a practical sense, this meant that the new Jewish immigrants to Palestine would be charged with tilling the fields, picking the fruit, drawing the water – becoming native.

This preoccupation with sunburned brows and rugged silhouettes marked Zionism apart from other nineteenth-century colonialisms. In Palestine, the idealised Jewish man would learn that he had no use for indigenous labour, only the land upon which it toiled. Zionism’s horizontal latticework – the Yishuv or early Jewish settler community – sought to project a positive vision of a natural world forced to yield to Jewish brawn. The invention of the New Jewish man, the Israeli, required the negation of the Palestinian. That was partly to entice European Jews into emigrating from their countries; indigenous resistance to immigration would have diminished the allure of the Holy Land.

But the erasure of the indigenous Arabs was also ideological. The foundational mythology told by Jewish storytellers about their heroes took form in a wild, untamed and unconquered landscape; an unpeopled landscape. It was written in long, flowery script that bloomed on clean, unspotted parchment. Harangued across the ages, the time had come for the Jewish people to forge their destiny in their spiritual foundry. The uncomplicated story of return and exile was successfully distilled into the facile language of mass politics. Today, most of us are familiar with Zionism’s most hackneyed rhetorical lozenge – that Palestine was a “land without a people for a people without a land”.

Of course, the land was peopled. And it was peopled by the indigenous Palestinian Arabs. They were the ones who built the port cities of Haifa and Jaffa and cultivated the citrus and olive groves. They were the ones who, with undeniably real minds and bodies, issued the most forceful moral rejoinder to a vision of a Jewish-only society in Palestine. “We are here,” they said.

But not for ever, as it turned out. The early Zionists had adeptly accumulated arms and political support in western capitals in preparation for the moment they knew would arrive. Plan Dalet was carried out with more success than could have been predicted: by the end of the war in 1948 most of Palestine had been successfully emptied of its Palestinian inhabitants. More than five hundred villages, where roughly 700,000 people had lived, were summarily razed; the erasure climaxed in an epic act of ethnic cleansing.

They were forgotten. Or rather, the founders of the state of Israel tried to forget them. In their minds and books, the state of Israel was heroic – God’s manifest will and his people’s benedictory return. The opportunistic Arabs who had arrived for material gain with the first Aliya had been vanquished. They fled at their leaders’ behests, or otherwise ceased to be. Israel was a trial-borne miracle.

The Palestinians did not forget, however. Their families learned to inhabit the dark peripheral spaces – the preserve of refugees. But they did not grow comfortable there. In their hearts they nurtured the memory of a place that they owned, fields that they tilled, weddings and births and funerals. Their thoughts burned with the late knowledge of their history; they had been exiled. Zionism had destroyed their towns and villages, but it hadn’t destroyed them.

Their young people collected themselves and began to fight. They fought for a life worth living, for home, for recognition. They fought in the alleyways of their refugee camps and in the streets of their conquered places. They fought with their words, their songs and their literature.

The memory of them – who they were, where they are from and who they are today – gradually began to shake the scales from the eyes of peoples around the world. In the East, they recognised the Palestinians’ worn faces and calloused soles; they were alike. In the West too, they were recognisable. Their fierceness was unfriendly and their righteousness threatening. They were the indigenous people clamouring for a reckoning – the barbarians at the gate.

That was in the 1960s and 1970s, when Golda Meir felt comfortable denying their existence entirely. “There is no such thing as a Palestinian people ... It is not as if we came and threw them out and took their country. They didn’t exist,” she said.2

The intervening decades saw the world change. The East grew, asserting itself and its own historical experience. The West grew too. Contrition over a past blackened by imperialism and colonialism became widespread, and recognition of indigenous peoples’ right to independent life and self-determination developed similarly. But the Palestinians stayed the same – and so did their Zionist adversaries.

Today, just as one hundred years ago, the denial of the existence of the Palestinian people is widespread amongst Zionists. Its superficial form has changed – instead of the Palestinians, it is Palestine that does not exist (the “Palestinians” can call themselves whatever they like). But the thrust is the same. The idea and the words used to produce the denial carry an emotional charge, a pugilistic readiness to fight over the “right of the Jewish people” to colonise and occupy all of Palestine. All the while, the denial wraps Israel in a plastic, impermeable sheath. The Palestinians did not exist – there was no one to dispossess. Palestine does not exist – wrongdoing cannot be perpetrated in a void.

Nor could the great historical extirpation of the Palestinians be consigned to 1948 or 1967. The cleansing of Zionist memories has been a high-maintenance and a continuous undertaking which has required diligence and an entire society’s energies. The cost of a single crack in the facade is too high. To stop denying the existence of the Palestinians would signify a readiness to confront the state’s original sin – the ethnic cleansing of Palestine. Israel would be de-sanctified and the cries, pleas, muffled shouts, and roars of a million refugee voices would burst forth in a deluge: “We are coming home!”

Zionism cannot withstand the decibel level. That has been true all along.

Israeli inculcators weaved their mythologies so tightly that the Palestinians ceased to exist, not only in history, but in the present as well. It is this manufactured non-existence of the Palestinians that has enabled generations of Jewish Israelis to steal and settle land in the Occupied Territories. It is that same dehumanisation that has enabled their larcenous governments to encourage their often violent activities. Today, the cataracts have grown so thick that when young Israelis move to colonise the West Bank, they do not see fellow humans. Standing in their way are the dehumanised, unchosen Arabs with inferior rights, or none at all. These are the memories they have been taught.

The process of purging memory has a strangely prophetic quality. The forgotten, erased, obviated, occluded, denied, clouded, wiped, blanked and stricken reaches its tentacular form into our present. Palestine existed, but it’s been colonised out of existence.

The transition from memory and imagination to reality can be an abrupt one. The unacknowledged truth is that Palestine/Israel is already one country. A visitor from another country will struggle to isolate one from the other. Artificial-looking Israeli settlements penetrate deeply and violently into the West Bank, cantonising the territory. Jewish-only roads snake heavily there; the sieve that strains Palestinian lives. All the while, Israeli pipes swiftly draw water from Palestinian aquifers beneath Gaza and the West Bank. The country is a unified one, but Apartheid’s ugly scrawl mars its surface.

This is a basic truth that Rick Santorum – another Republican politician – inadvertently bungled into when he said that: “All the people that live in the West Bank are Israelis. They are not Palestinians. There is no Palestinian. This is Israeli land.”3 Santorum sought to deny the existence of the Palestinians – to erase them. But he mangled the lie and unintentionally claimed Israeli citizenship for the two-and-ahalf million Palestinians who reside in the West Bank. In essence, his words were a tidy summation of the spiral history of Zionism: there are no Palestinians, and Israel is an Apartheid state which disenfranchises half its citizens. The Palestinians have been unremembered, yet there they remain.

Memory and Reality

My family lived in the West Bank at the height of the Oslo process in the mid- to late 1990s. Even at that time, I remember thinking that the settlements around us were immovable; they were fortresses that rested heavily on a now spoiled landscape.

My father wanted to show us as much of the country as he could, so we took weekend trips to different sites in the West Bank. Jerusalem and Israel were closed to us. I remember winding drives from one valley to the next and the oppressive sense that we were being locked in. Even at that time. the road system in the West Bank was segregated. For me, that was an early hint of how things were supposed to develop.

It was around that time that I began to think that the discussions and handshakes being broadcast into every occupied home were a sham. Our lives were getting more difficult almost on a daily basis. Yet the news anchors insisted that Jericho was now free, Ramallah was nearly there, and that Jerusalem would come next.

The second intifada started in the summer of 2000 and my family left Palestine. It was probably in 2002 or 2003 that I realised that there would never be a viable Palestinian state. That awareness didn’t bother me very much because the knowledge that anything Palestinian would be truncated and crippled by an immensely more powerful Israel had developed by that time. So it didn’t make sense to mourn a non-state where non-self-determination would take place.

That was also around when Tony Judt published his essay “Israel: The Alternative” in the New York Review of Books.4 The essay had a tremendous impact on me. I wasn’t aware that the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) and others had called for a binational state decades earlier. All I saw was an alternative, one that could provide justice for the refugees and everyone else. The Palestinians had a way out, a path to freedom. The years that followed saw the violence in the Occupied Territories and Israel explode. When the intifada was stamped underfoot and snuffed out, Palestinians were left with nothing to do but count the dead. It was a very dark period, morally and spiritually, for many of us. We had resisted the erasure, the deliberate forgetting, and we had forced the Israelis to acknowledge our existence. But at what cost?

I travelled back to Palestine for the first time in a decade in December 2010. Everything I remembered was still there – kind of. The world had changed; mobile phones were ubiquitous, USAID money had transformed Ramallah into something that looked relatively prosperous, and some of the cars were newer. There was even a Mövenpick. But the starkest changes were most obvious and irreversible. The settlements had taken over and much of the bucolic landscape had simply stopped existing. I’d known it had happened, but I was still deeply saddened to see it.

I also knew about the Wall. But confronting it turned out to be more difficult that I had imagined. My old neighbourhood of Al-Ram had been ruined and partially de-peopled by the Wall which was built through the heart of the town. It weighed heavily on Palestinians; tons of vertical concrete can do that. In Bethlehem, too, I was stricken, both by its size and by the brazen offence it offered to anyone who chose to visit the holy sites there. I once believed that the world’s Christians would speak up in the face of desecration, but I was wrong.

That trip was an important one for me. I saw at first hand for the first time in a decade that Palestine was gone – there was nothing left. The two-state outcome was dead. I had borne witness to the fact.

The Presence of Morality

The second intifada succeeded in reasserting the existence of the Palestinians but it failed in almost every other way. For many Palestinians the exclamatory statement was a costly one to make. Thousands of them were killed by Israel, which also lost more than a thousand civilians to Palestinian violence. By the end of 2004 the Palestinians were worn, tired and dispirited. But the basic dilemma remained: how to resist oppression and Apartheid, and how to do it in a way that did not diminish their moral claims?

The answer came through the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movement. Palestinian civil society united in 2005 to issue a near-unanimous call for non-violent resistance to Israel. The movement recaptured and highlighted the moral core of the Palestinian claim and broadcast it widely to the world.

Modelled on the South African call, which helped to bring about an end to Apartheid in that country, the BDS movement has seen an increase in effectiveness with every passing year. That has been particularly true on the cultural boycott front, which is the most important for effecting change. Some Israelis have begun to acknowledge the offensiveness of their Apartheid regime, but only after popular musicians like Coldplay began to refuse to play in Tel Aviv. The key here is that the Israeli occupation will continue to be maintained so long as the majority of people in that country can continue to ignore it. The BDS movement makes it harder to ignore Apartheid.

It is important to remember that BDS is not an outlook, an article of faith or a panacea. Nor will it likely be a tool for economically undermining the occupation; moneyed interests run too deep. Besides helping awaken the Israelis to the suffering they cause, BDS is a tool with which the Palestinians can highlight their moral claims to a receptive international audience. That is especially true for people who may not feel completely authoritative when talking about a just solution to the “complicated” Palestinian–Israeli conflict. BDS helps to simplify and distil the Palestinian message because the call is fundamentally about upholding human rights and ending the occupation. In that context, many people around the world can speak with power about the necessity of ending Apartheid.

But BDS is not enough.

For some Palestinians, the call for an end to occupation and Apartheid has accompanied a positive vision for the future. Working to overcome the barriers to self-determination has also meant transitioning from one definition of what being a Palestinian means to another conception entirely. It has meant abandoning the struggle for a Palestinian state and adopting the struggle for equal rights in its place.

It is easy to recognise the necessity of ending the occupation, particularly when Palestinians effectively communicate the urgency and durability of their cause. It has been more than sixty years since the first refugees settled into their tented encampments – the original refugee camps. And for all those years their basic rights were never upheld – not by the Egyptians, the Jordanians, the Israelis, the Syrians, the Lebanese, or anyone else.

The message broadcast by the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) for all those years was one of national self-determination. The theme dominated the discourse of the developing world throughout the twentieth century, so it was no surprise that the Palestinians also adopted it. But the focus on national rights failed to convey the urgency of the plight of the refugees and the humanitarian dimension of their struggle to people around the world. For many, the Palestine problem was fundamentally about creating a state for a stateless people. Therefore, any solution for the refugees could only come through the creation of a state; a political solution for a humanitarian problem.

The call for a one-state solution eliminates all of the confusion around the right of the Palestinians to live free, unmolested lives with full dignity. The Palestinian–Israeli conflict is no longer inaccessible to the layperson because it is about rights and Apartheid and ethnic privilege. One does not need to know the history of a centurylong struggle to understand that something is deeply wrong with the reality today and to stake a position on that basis. It is now enough to know that there are roads in the West Bank that are restricted to some people because they possess certain unalterable traits.

It is also meaningful that the equal rights message resonates in the American context. That is important because of the outsized role the American taxpayer plays in maintaining the occupation. Europeans can understand what occupation is because it was something they experienced during World War II and its aftermath. In the postcolonial world, life in the context of European settler-colonialism is similarly easy to remember. But the American experience carries no recognisable historical parallels to the Palestinian situation when it is framed as a quest for a state. The American revolutionary period is a distant memory that bears little resemblance to the twentieth-century occupation experience. That’s not true about the equal rights struggle, however. Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King are alive in the national spirit of the United States – and they are the best-fit for understanding what is really happening in Israel/Palestine.

The question of how to arrive at equal rights in Israel/Palestine is an open one, with which many of us are currently engaged. It is an urgent question, and I suspect that the answer lies partly in the BDS movement. But a full discussion of how to get there and what the single state will look like is beyond the range of this essay. For now, it is enough to say that many people of good will around the globe and in Israel/Palestine are currently grappling with how to achieve the most just and moral outcome for everyone in the country.

At the same time, their adversaries are working to preserve Jewish privilege in Israel and the Occupied Territories. Despite the efforts of increasing numbers of activists and others, much of the American political establishment, the Israeli establishment, and the Palestinian establishment (who are mainly affiliated with the Palestinian Authority) are working to produce the Bantustan option – a series of non-contiguous Palestinian cantons in the West Bank governed by a corrupt elite subset of society.