20,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

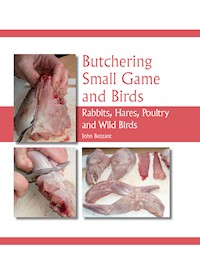

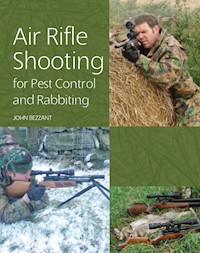

The air rifle is a very effective weapon for the control of rabbits and vermin. This clearly written and fascinating book covers the following topics in a practical and thorough way:

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

Copyright

First published in 2009 by The Crowood Press Ltd, Ramsbury, Marlborough, Wiltshire, SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book edition first published in 2012

© John Bezzant 2009

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

ISBN 978 1 84797 407 5

Disclaimer The author and the publisher do not accept any responsibility in any manner whatsoever for any error or omission, nor any loss, damage, injury or liability of any kind incurred as a result of the use of any of the information contained in this book, or reliance upon it.

Acknowledgements I should like to acknowledge Peter Martineau of BSA Guns and Tony Gibson of Deben Group Industries for their invaluable technical support and advice in the production of the book.

Credits All photographs by David Bezzant. Line drawings by Keith Field.

Contents

Title Page

Copyright

1 Teaching Yourself to Shoot an Air Rifle

2 Suitable Weapons

3 Scopes

4 Ethical Aspects of Air Rifle Hunting

5 Ammunition

6 Know Your Quarry

7 Fieldcraft and Field Equipment

8 The Law

9 Maintaining Your Hunting Rifle

Appendix I: The Bazooka

Appendix II: Kill Zones

List of Suppliers and Manufacturers

Glossary

Index

CHAPTER ONE

Teaching Yourself to Shoot an Air Rifle

THE AIR RIFLE’S PURPOSE

There are two tasks to which the air rifle is generally put: pest control and rabbit hunting.

Pest Control

Pest control often takes place in barns or industrial buildings. Using a firearm or shotgun in such locations would obviously lead to serious damage occurring to the fabric of the building. This would make you most unpopular with the property’s owner, but beyond this there is the question of safety.

Pest control takes place at very close range, so any weapon more powerful than an air rifle will send its projectile zipping straight through the quarry like a missile. It has more than enough surplus energy remaining to cause serious, even fatal, injuries to stock, farm workers, or the shooter himself.

Within buildings, the use of firearms is highly likely to result in ricochets. This occurs when a projectile passes clean though the quarry, strikes something hard (such as a wall) and bounces off it. The shooter has absolutely no control over a ricocheting bullet: it can go anywhere.

In barns and industrial buildings, there may be animals or people in the locality; this, combined with the ricochet factor, is a recipe for disaster. It is also entirely possible that the person firing the gun could end up being the one that gets hurt. I know of an incident in which a highly trained soldier was killed by a ricocheting bullet fired from his own weapon. Only an incompetent fool would choose to use a firearm within the confines of a building.

Another problem with firearms, when it comes to pest control, is the fact that they are not able to deal with the large number of pigeons that have to be taken in one go. In a morning I can take forty pigeons from a single building. In the larger industrial buildings, it is possible to take a hundred or more pigeons in quick succession. The reason for this is that a firearm discharges its projectile by causing a small, controlled explosion within the barrel. A side-effect of the explosion is heat, which will shortly start to have a detrimental effect upon the weapon’s accuracy. As few as ten to fifteen rounds can be sufficient to affect accuracy. Air weapons do not have this problem: they can fire a hundred pellets in quick succession without their accuracy being affected.

Rabbit Hunting

Several factors make the air rifle, rather than a firearm, a more suitable weapon for rabbit hunting. Firstly, landowners are often willing to let a person on to their land to hunt rabbits with an air rifle, but would not be willing to grant that same permission to someone with a firearm. They understandably believe that the potential for accidental injury or damage to property is far greater when a firearm is employed.

Secondly, quite a lot of land is not suitable for the use of firearms. This includes fields with roads or footpaths near by, or fields that back on to houses. Any fields that contain stock or surround a farmhouse or farm buildings will probably be off limits. Not so with the air rifle.

A firearm may outstrip an air rifle for sheer power and range, but that power has a downside. Any shot that misses a rabbit can travel a considerably long way, 220yd (200m), say. As a consequence, a firearms user has to satisfy himself that behind every target he shoots at there is something that can act as a backstop to absorb the bullet if it misses the target.

A bullet is a lethal projectile. Therefore, the shooter has to be 100 per cent positive that a miss will find the bullet going to ground long before it reaches an environment where it can do any damage. This places a very high degree of responsibility upon the shooter. Air rifles do not present the shooter with that kind of responsibility, meaning that the shooter can discharge an air rifle with a far greater degree of confidence. This is a point well worth considering: a stray bullet that causes damage or injury will expose the shooter to criminal prosecution and/or possible civil litigation.

Air rifles have to be used with care, but their lower power levels make them a lot safer to use than firearms. A firearm will exhibit a muzzle energy of about 1,000ft per lb. A non-FAC (Firearms Certificated) rated air rifle will, in comparison, produce no more than 12ft per lb muzzle energy. Even an FAC-rated air rifle will not go much above 40–80ft per lb. These figures dramatically demonstrate how much safer an air rifle is to use than a firearm.

Firearms are very noisy. Even your humble .22’s noise scares those who are not used to hearing it; it also scares dogs and livestock. But a modern air rifle fitted with a state-of-the-art silencer hardly manages to whisper. This has obvious advantages. Firstly, you will not scare the landowner or his neighbours; secondly, you won’t scare off every rabbit for miles around when you discharge the weapon.

COMPARISONS

At the time of writing, a decent .22 bullet rifle will set you back in the region of £500 to £600, whereas an air rifle of similar quality can be purchased for £250 to £350. But the real saving comes with the ammunition. Pellets are a tenth of the price of the cheapest bullets.

A shotgun, unlike an air rifle, can be used to take moving targets. This is because the shotgun spreads its load over a wide area. However there is a downside: the quarry is peppered with hundreds of tiny pieces of shot. The person preparing the meat for the table may be very diligent indeed but, no matter how hard they try to remove all the shot, some of it always remains undetected – most unpleasant to discover in the mouth when you’re eating. An air rifle delivers a much more surgical strike, because only a single pellet is used to take down the quarry, usually in the head –a part of the animal that is not eaten.

How Clean is the Kill?

Many people think that the low level of power produced by an air rifle means that these weapons do not have sufficient punch to kill an animal cleanly. A non-FAC-rated air rifle can have a maximum muzzle energy of 12ft per lb; it only takes 4ft per lb to kill a rabbit if shot in the head. So when a pellet leaves the barrel of an air rifle, it has three times more energy than that required to kill a rabbit. But it’s not quite as simple as that: a pellet on its flight from barrel to target constantly loses energy as a result of drag.

What we need to know is, how much of that initial 12ft per lb will be left when the pellet eventually strikes the rabbit’s head. This depends upon the range and upon the type of pellet you use, but the following table gives a fair indication.

From the chart overleaf you can see that even at 40yd (36m), the air rifle can deliver a pellet with almost twice the level of energy required to kill a rabbit.

THE AIR RIFLE HUNTER

Is it possible for a complete beginner to teach himself how to shoot? Yes, but it won’t be a walk in the park. This book has been put together in such a way that it can be used as a self-teaching training manual, equipping you with everything you need to know to become a competent hunter.

Hunting quarry with an air rifle has to be humanely carried out. Thus, the air rifle user must be a competent marksman. To become a marksman involves a lot of work, and discipline akin to that exhibited by those who engage in athletic sports. You have to know how ammunition behaves, be thoroughly conversant with the workings of telescopic sights, have the ability to read the weather, possess a broad knowledge of animal behaviour, be able to utilize fieldcraft to blend into the outdoor environment in which you are hunting, and finally be able to handle your chosen weapon.

All the required skills have a theoretical element that must be tackled through the avenue of serious study. Then there is the practical side: hours upon hours of practice are necesssary if you want to turn all the hard-won theory into a usable skill.

Marksmanship is a skill acquired by those who commit a large amount of time to long practice sessions on the range; this hones the skills to the level required by those who want to shoot at living creatures. Marksmanship is a perishable skill, and if you do not practise on a regular basis it will fade. Competitive target shooters will practise every single day to keep their skills in tip-top condition. The serious hunter needs to be finding the time for at least one session on the range every week.

Attributes

In addition to the hours of practice, there are some personal qualities that an individual requires if he is to become a competent hunter. Many people go and spend a small fortune on an air rifle and accessories in order to take up air rifle hunting, only to discover that they are not at all suited to the sport. To save you wasting your money, I have put together a checklist of the physical and emotional qualities that the hunter needs to possess. When looking at this list of attributes, try to be brutally honest with yourself to discover if you are the type of person that can enjoy hunting.

Good Physical Health

Hunting and pest control require the shooter to spend extensive periods of time in the outdoors, often having to combat inclement weather conditions. It is not uncommon to cover anywhere between 5–13km (3–8 miles), on foot, in a morning. Such walking requires a decent degree of physical fitness, specifically strong legs and a good cardio-vascular system. An unfit hunter will succumb to fatigue, which has a detrimental effect upon marksmanship. Good physical condition will mean sharp reflexes and good muscle control, both essential ingredients in the recipe for a good marksman.

Good Vision

Eyesight is obviously one of the marksman’s most vital tools. Therefore, good eyesight is essential. This does not preclude those wearing glasses, as long as the glasses are able to give the wearer a normal range of vision.

A Strong Sense of Personal Responsibility

Air weapons are very powerful weapons, so should be handled by those who possess an innate sense of personal responsibility. Those who handle an air rifle must do so in such a way that it does not endanger others or cause any suffering to the quarry. Sadly, vast numbers of rifles are in the hands of those who do not posses this quality, which is why so many air rifles are used in so many crimes. As a result, it is likely that in the not too distant furture possession of an air rifle will require a licence.

Emotional Toughness

Using air rifles to shoot quarry involves the taking of life, which is not, and should never be, pleasant. There will be blood, and sometimes there will be injured quarry that you will have to finish off with your bare hands.

Being able to deal with this requires a degree of emotional toughness, which does not mean that you must have a cruel streak, but that you must be able to kill in a calm, rational manner. Anxiety and fear of remorse will make you a hesitant shot, resulting in injuries rather than clean kills.

A Feeling for the Outdoors

To become a good sporting marksman able to take quarry cleanly, you will need to acquire a high level of fieldcraft. Aquiring this is possible only if you are a person who enjoys being in the outdoors.

CONSTRUCTING YOUR OWN 40-YARD RANGE

Before you can even contemplate firing an air rifle, you have to provide yourself with a suitable practice area. This means a properly constructed practice range, with sufficient length to allow the shooter to place a target 40yd (36m) away from the firing position. The range does not have to be any longer than 40yd (36m), as this is the absolute maximum range at which quarry should be taken. The rationale behind shooting on a properly constructed range is quite simple.

Modern hunting air rifles are powerful weapons specifically designed to kill. This means that a pellet fired from such a rifle has the capacity to penetrate tissue and smash through thin layers of bone, including those of a human. Usually, when a person is hit accidentally with an air rifle pellet, it is nothing more than a painful flesh wound. But wounds causing permanent disability, even death, are not unknown.

It is clear that practice sessions must take place on a range, and that a bit of board propped up precariously in the back garden is totally inappropriate. You may choose to join a club to access such a range, or you may, like me, decide to build your own. But before going on to the actual construction of the range, it’s well worth pausing for a moment to answer a reasonable question that is often posed: Why begin with targets?

Targets

It is essential that you restrict yourself to shooting targets until you are competent enough to hunt live animals. They are the ones that will suffer horribly if you make a hash of it. Very few people are naturally gifted marksmen. For most, marksmanship is a skill hard won through hours of dedicated practice. If you were to go straight out into the field and start shooting at rabbits or birds you would have few, if any, kills. You would also cause an awful lot of suffering to the creatures that you would undoubtedly injure in some way, resulting in a slow, lingering death.

An air rifle pellet is a light, small projectile. It can only cause sufficient shock and injury for instant death if it is accurately placed into a small area of the quarry’s body, referred to as the kill zone – usually the head area.

The kill zone will be no bigger than a pound coin. Hitting that at a distance of 30–40yd (25–35m) takes a considerable amount of skill. To acquire this skill, you will have to begin with targets and put in weeks of serious training, sticking at it until you achieve a 1in (25mm) grouping – considered the benchmark for humane hunting. This means being able to place three consecutive shots into an area that can be covered by a 1in (25mm) circle.

Siting Your Range

I live on a smallholding with a five acre field behind the house, so finding somewhere for my range presented me with no problems. However, if you don’t live on a smallholding don’t worry; your garden may well suffice if it can spare you an area 40yd (36m) long and 6½ft (2m) wide. In fact, you could just get away with an area slightly smaller: 30yd (27m) long and 1yd (1m) wide.

A garden is private property; if you are the owner of that property you have a legal right to shoot on it as long as your shots do not stray onto other people’s land – they won’t if you have a properly constructed range.

A modern air rifle fitted with a silencer is very quiet, so neighbours should not be disturbed by your practice sessions as long as you are sensible in your selection of targets. A pellet passes clean through a paper target silently, but a metal target, of which there are many on the market, will produce a plinking sound every time you strike it: a sound that will quickly grow irritating. Think before you shoot.

Range layout.

Range Layout

The piece of ground that you select for your range site needs to measure 30–40yd (25–35m) in length, and 1–2yd (m) in width. It is self-evident that the area chosen has to offer a clear line of sight from the shooting position to the target area. A flat piece of ground could be used, preferably it should have a steady slope from the target area down towards the shooter. Should you miss the backstop, a most unlikely event, the pellet will be caught by the high ground.

The area behind the backstop should be designated a safe zone: 20yd (18m) in depth and 10ft (9m) in width, in which nothing that could be damaged or hurt resides: a greenhouse or grazing cow for example. The safe zone should be open fields or the like. Some modern air rifles can propel a pellet out to a distance of 60yd (55m). In the unlikely event that you miss the backstop, the 20yd (18m) safe zone ensures that the pellet loses all of its remaining energy in an environment that is under your control.

If you do not have sufficient room to facilitate a safe zone behind the range, you can increase the width and height of your backstop: from 4 × 4ft to 6 × 6ft (1.5m × 1.5m to 2m × 2m). Nobody could possibly miss a backstop of that size.

The area between the shooting position and the backstop should be grass or earth, not a hard surface such as concrete. Hard surfaces can cause ricochets which are unpredictable in nature and thus dangerous. The range area should be completely fenced in, so as to prevent pets or people wandering into the line of fire during practice sessions.

Safe handling of an air weapon is the foundation stone on which marksmanship is built. In the RAF, where I learnt to shoot in the 1980s, safety was hammered into me over and over again until it became instinctive; only with this kind of approach can you ensure that accidents do not happen. A bit of wood or a cardboard box propped up in the back garden for practice sessions just will not do.

Construction of backstop.

Constructing the Backstop

A backstop is basically a wall with sides made out of stout material, such as bricks or wood, which is filled with a substance that can absorb a pellet in flight bringing its forward momentum to a rapid halt. Sand is usually that substance, but earth would do just as well as long as it’s stone free. One stone in the soil, even a small pebble, could cause a ricochet. The way to ensure that the soil is stone free is to sieve it.

The earth or sand has to have sufficient depth so as to prevent a pellet passing through. The earth or sand is required to be 4in (10cm) at its shallowest point. To achieve this the slope must begin with a base of 2ft (50cm), which will decrease slowly as it grows in height, reducing to 4in (10cm) in depth when it peaks at a height of 3ft (1m). This will require a good tonne of soil or sand.

Construction of a firing position.

Constructing the Firing Position

The firing position is simply a place from which you shoot. It should be precisely 30yd (27m) or 40yd (36m) away from the base of the backstop. The firing position can be a small shelter that protects the shooter from the weather, or simply a board on which to kneel or lie. Whichever option you decide to use, it is a good idea to have a couple of firing supports: one to correspond to the kneeling position and another to the standing position.

Wind indicators and distance markers.

Wind Indicators and Distance Markers

To finish the range off properly you need to add a couple of wind indicators and a series of range markers. Wind indicators are there to tell you which direction the wind is coming from and how strongly it is blowing, which is vital information that is key to the correct placement of the shot. A wind indicator is easily made by placing a baton to either side of the backstop. The baton should be about 6½ft (2m) in length, with a thin 1ft (30cm) length of lightweight material attatched to the top of it.

Range markers are offcuts of wood painted in a bright colour. They are knocked into the ground along the edge of the range at precise distances (in yards) from the firing position: 10, 15, 20, 25, 30 and 40. The ability to judge distances to within a few inches is of the utmost importance, as it will enable you to place your shot on the correct trajectory to strike the target at the required mark. The closer something is, the lower you aim; the further away something is, the higher you aim. The distance markers will help to teach you the skill of range-finding.

Target placement.

TARGETS

Now that you have a safe place to shoot you will need something to shoot at. Targets are the obvious choice, but what sort? There are so many to choose from.

To begin with, you will need some traditional-type targets with a number of rings that decrease in size as they move toward the centre. These targets will be needed to set the sights on your rifle, including both open and telescopic sights. These targets will allow you to calculate the adjustments that need to be made to the sight’s windage and elevation settings, so that you can calibrate the sights to suit the individualities of your eye. Do not worry – this is not as complicated as it sounds.

Range Safety

Before you can start to put your newly constructed range to good use, you must first have a clear understanding of range safety. The ‘dos and don’ts’ that must be followed at all times

Always have the barrel of the rifle pointing down the range; even when you know for a fact that the weapon is unloaded.Always have the safety catch applied until you are in the firing position and ready to take aim.Never leave a loaded weapon unattendedAlways wear safety glasses in case of a ricochet. Ricochets on a properly constructed range are most unlikely, but the unlikely does sometimes happen and if struck in the eye, the shooter may be blinded for life. Safety glasses for shooting purposes can be purchased very cheaply.Never allow anyone to enter the range area whilst firing is taking place.When you have learnt the basics, you will need to move on to a target that depicts the type of quarry you intend to shoot. These targets should be life-sized, with the kill zone of the animal or bird depicted by a small discreet circle. I do not like targets that have the kill zone depicted in some vivid colour that can be seen from miles away. Real quarry does not come with a red dot stuck to its vulnerable areas, so they must reflect reality. Realistic targets will not only reveal the level of your marksmanship, but will give you a good idea of what the real thing will look like at different distances. This is why you will need to practise on the target across the full spectrum, from 10yd (9m) right out to 40yd (36m).

The final type of target that’s worth having for the range are the knock-down metal targets used by field target shooters. These targets are the silhouette of an animal or bird cut in metal; somewhere on the silhouette a 1in (25mm) hole is drilled out; behind it a disk is inserted that is connected to a knock-down mechanism. Hit the disk and the target falls down flat, it can be reset by pulling on a length of cord. These targets are great fun for practice sessions.

With paper or card targets you will need something to hold them; all four corners have to be held down or they will blow up in the wind. You could pin your paper target to a board with drawing pins, but it seems a waste of a good wood, especially when a simple target holder can be purchased quite cheaply. The target holder is made of metal rods which, when screwed together, form a cross shape with two crossbars; the bottom is adjustable so that the holder can accept any size of target. Use bulldog clips to fasten the target between the two crossbars. The target holder has a three-pronged foot on the bottom of its upright, which enables it to be driven easily into the ground. A target holder like this can be acquired from Deben Group Industries (see page 148).

Target placement upon the range must be carried out with great care. Whether the target is right at the base of the backstop or just 10yd (9m) away from the shooting position, you want to make sure that the centre part of the target lines up with the deepest part of the backstop. This will give plenty of leeway should you happen to fire a bit too high. If you set your target too high, then a high shot will go straight over the range.

CHOOSING A RIFLE

Now that you have constructed your range and set up a few targets, you need to choose a weapon that you can learn to shoot with. Basically speaking there are two main types of air rifle: those powered by a spring piston and those powered by a compressed air cylinder. The latter are known as pre-charged pneumatics (or PCP for short).

Recoil phase.

Spring-Piston Rifles (Springers)

When you pull the trigger on a spring-powered rifle, the depressed trigger operates a lever that releases the spring piston; this hurtles down its chamber forcing air into the barrel, thus sending the pellet on its merry way. The release of the spring causes a dynamic reaction known as recoil, which simply means that the rifle moves when fired.

There are three distinct phases to this movement. Firstly, the rifle moves backwards into the shoulder in reaction to the air being forced from the cylinder. Secondly, the backwards movement is then almost instantaneously met and overcome by the forward momentum, created by the spring travelling violently forward. Thirdly, when the spring hits the front of the cylinder like an express train, it rebounds and the force is once more in a backwards direction.

This movement of the gun (recoil), has to be skilfully managed by the shooter or it will have a devastating effect on accuracy. In short, the recoil of a spring-powered rifle forces the shooter to adopt proper techniques, as it is a most unforgiving weapon that will not tolerate the slightest error in technique.

The PCP Rifle

The PCP has no recoil and is therefore very easy to shoot, being incredibly forgiving of poor technique. With a PCP it is possible to achieve a passable level of accuracy whilst exhibiting a fairly poor technique, though to become a really good shot the technique has to be brought up to scratch. Learning to shoot with a PCP is a bit like learning to drive in an automatic car because the gun does a lot of the work for you.

So which should you choose: a spring-powered or a PCP? Many experts tell you that there is no difference in accuracy between them, which is true enough if you happen to be an expert marksman. (There are guys out there who can split the atom with a single shot.) For the complete beginner and the mere mortal, that is not the case at all.

I have recently been coaching a young lad who had never used an air rifle in his life before. I started him out with a PCP, and after only two half-hour lessons he was beginning to pull together a reasonable grouping. When, however, we moved on to a spring-powered weapon the target looked like it had been peppered by a shotgun. Spring-powered weapons with their violent recoil are much harder to tame than any PCP.

I find that a PCP can give me a tighter grouping than I can achieve with a spring-gun. With the very best PCPs, I am able to put a succession of three shots almost through the same hole on the target. So yes, it is true that tremendous accuracy can be achieved with the spring-powered weapon in the hands of a really good technician. But that kind of skill does not come easily – to some it never comes at all – the only way to purchase such skill is to spend hours upon hours practising on the range.

The late John Darling, an airgun hunter of great renown, used a very powerful spring-powered weapon for many years with great success. However, when the first really good PCP came along the springer was shelved and the PCP took its place.

PCP or Springer?

I am quite a fan of spring-powered weapons. One of my biggest pigeon bags ever was taken with a very simple medium-powered springer, but it has to be said that PCPs are an awful lot easier to use. I just cannot achieve the levels of accuracy with a springer that I can with a PCP. Some may say that the reason for this is that my technique is not good enough, but you just have to take a look at the scores at any field target shoot, and you will see that those using PCPs are achieving higher scores than those using springers.

One of the other problems you will face with a springer derived from its violent recoil: a more frequent loss of zero than occurs with a PCP. Basically, the springer’s recoil shakes the rifle aboutabout, which moves the cross-hairs fractionally away from the line to which you zeroed them. They will have to be reset. The PCP does not have such bad behaviour.

Before you go off with the idea that spring-powered weapons are a total waste of time, being more trouble than they are worth, let me highlight their good points. Price for example, a good spring-powered rifle can cost half the price of a PCP, which is an important consideration as not everybody can afford the £400 to £700 price tag that most PCPs carry (in 2008).

Not only is the springer cheap in comparison to a PCP, it is a much simpler form of construction, therefore it takes less skill to maintain and repair; putting it within the scope of the moderately competent DIY-type, operating out of a garden shed or garage. Moreover, if rifle customizing is your particular interest then the springer is the chap for you, as there is so much that you can do to it.

A springer is also, owing to its simplicity, more rugged than the PCP and will cope better with rough handling.

My rifles take a real hammering in the field, I give them no quarter whatsoever. They are exposed to all kinds of weather, they get filthy, knocked against hard objects and rested on all kinds of surfaces that are abrasive to wood and metal. In my experience, the springer endures such treatment more manfully than the PCP. Knowing that my kind of shooting – crawling around farmyards and clambering over rubbish tips – is so brutal on a gun I prefer to spend less on a weapon, which rules out most PCPs. I can get a good springer that will last for years more cheaply than I can buy a PCP.

Another advantage that the springer has over the PCP, is its independence. The springer is totally self-powered, all it requires is a few good arm muscles to force back the spring, the PCP needs an air source. That air can be provided by an air-cylinder or a hand-operated stirrup pump. The PCP is therefore not a pick up and go weapon, it needs to be charged prior to use. Whereas, the springer is constantly ready for action, nothing needs to be done: just take it and go. This is one of the reasons why so many busy pest control operatives opt for a springer. To help you decide which is the best rifle for you, consider the following points.

Budget

Know exactly how much money you have in the kitty to spend on a rifle. Do not get trapped in the idea that the more expensive the rifle the bigger the bags will be; that is not the case at all. Some of my biggest bags have been had with a secondhand BSA Meteor, bought for less than £80; some of my smallest bags have been taken with a top of the range PCP retailing for a staggering £740. So just forget the notion that money equals success: the more expensive guns may be easier to use but they are not going to increase the bags.

Another thing to bear in mind is that the appearance of a rifle is irrelevant. Airgun manufacturers put a lot of effort into turning out aesthetic works of art to attract the eye. Looks are, from a hunting or pest control perspective, of no importance. Performance is all that matters when you are in the field; a beautiful walnut stock and gleaming metalwork do not kill rabbits. An accurate barrel, crisp action and heavy knock-down power are the things that count. Ask yourself what it can do, not how attractive it is. Multi-shot weapons are obviously more expensive than the single-shot ones, so does the hunter or the pest controller have to have a weapon with a multi-shot capacity to achieve results?

Having a multi-shot capacity does obviously make things somewhat easier. There is no fumbling around for the next pellet – it’s there in the magazine waiting to be deployed – which is supremely helpful if you happen to injure your quarry because you can quickly take a second shot. But you do not need a multi-shot weapon to achieve satisfactory results.

I remember last year taking my single-shot BSA Meteor to a cattleshed full of feral pigeons. I took forty-five of them in just a few hours, so you don’t have to have a repeating rifle to fill your bag.

A repeating rifle is a pure luxury item, something that is nice to own and use, but no more successful at killing quarry than a more wholesome single-shot weapon.

Before making a final decision, ask yourself what kind of shooting you are going to be involved in – the kind of environment rather than the quarry you are seeking. Is the environment going to be reasonably clean and kind to your weapon, or is it going to be dirty and brutal? If your shooting falls into the latter category, do you really want to be spending the price of a reasonable secondhand car on a PCP?

Pretty woodwork and shiny metal do not stay that way for long once employed in a rugged environment, at least they don’t with me up here on the northeast coast of Scotland. Which is why all that I am interested in is practicality not looks. Looks fade rapidly; practicality endures.

The unassisted prone position: there is nothing but human endeavour to support the rifle.

SHOOTING TECHNIQUE

The Hold

I shall look at the hold in four basic firing positions, which are the prone position, the kneeling position, the standing position and the sitting position. Learning these four positions should give you sufficient scope to meet most of the situations you encounter whilst hunting or carrying out pest-control operations.

The sniper training manual used by the American forces states that the sniper should always provide the rifle with an artificial support. This means that the sniper should not try to support the rifle by the efforts of his body alone, but he should find something to rest the rifle upon. This is known as an assisted hold, which can be employed in the prone, kneeling or standing position.

The unassisted kneeling position.

The reason for employing an assisted hold is to counter the effects of something called ‘wobble’. When holding a rifle unassisted, no matter how good the technique, the effort of holding the rifle in the firing position places the muscles under a degree of tension, causing the arms to shake very slightly. This wobble obviously has a detrimental effect upon accuracy. If wobble is not controlled you will never hit the centre of a target. Good technique can heavily reduce the effects of wobble, but resting the rifle on a solid object can almost eradicate the influence that wobble has on a shot.

Like the sniper, the hunter and pest controller should, where possible, use an assisted hold to make his shot, as it is simply the most accurate way to shoot. But there is a problem with spring-powered weapons because they do not like being rested on a firm surface. Hard surfaces resist the rifle’s natural recoil cycle, causing the pellet to veer dramatically away from the point of aim. There are, however, a few things that can be done about this.

There are bipods designed to be used with spring-powered weapons. A bipod is basically two legs that are attached to the barrel; it has dampers that prevent it from resisting the rifle’s recoil. These days, all sniper weapons are fitted with a bipod because they provide such a stable platform from which to take the shot: every airgunner should make a bipod a part of his basic kit.

The unassisted standing position.

An alternative sitting position for the less flexible like me.

When using a spring-powered rifle, I carry in my pocket a sand sock – an old sock filled with builders’ sand and tied around the top with a piece of cord to prevent the sand escaping. (The finished article resembles a cosh, so make sure you don’t wander around in public places with it still in your pocket or you might end up having to do some explaining to the police.) The sand sock can be placed on top of any suitable hard surface that provides a rest for the rifle – the top of a fence post or a car bonnet – the rifle’s barrel is then placed upon the sock and the sand prevents the rifle from being affected by the hard surface beneath.

An unassisted kneeling position.

If you are using a PCP a sand sock is not necessary, PCPs can rest happily on any kind of surface, hard or soft, without being affected in the least.

Very occasionally there isn’t anything around to act as a support. On such occasions it may be necessary to use an unassisted hold; these take a lot more skill to master than an unassisted hold and should only be used as a last resort. The percentage of first-shot strikes, when comparing assisted and unassisted holds, is dramatically higher for the assisted hold.

One of the main objectives of the airgun shooter is to take his quarry cleanly with the first shot; the assisted hold is the best way to achieve this objective.