Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Inkandescent

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

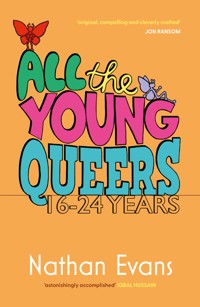

Following on from One Last Song—Evans' debut novella about queer elders—his debut short story collection journeys the other end of the rainbow spectrum, and will be published in February 2025 to mark LGBTQ+ History Month. In nine stories spanning from the end of the twentieth century to the end of the world as we know it, he explores our youthful years through a character of each of the ages between sixteen and twenty-four—ages oft tick-boxed together. Set in shiny cities, stuffy universities and other alternative universes, they explore issues from class to climate-crisis and chemsex with tenderness, humour and inventiveness. "original, compelling and cleverly crafted" – Jon Ransom "A wonderful collection of bildungsroman stories, full of vibrant characters finding their place in a jaded world. Evans beautifully captures the steep learning curve of each young protagonist, characters who must traverse religious, social, political and sexual dilemmas in order to discover who they really are. Evans is not afraid to play with voice and structure, making this a smart, insightful collection, where every story sparkles with rich, engaging prose and the perfect balance of humour and poignancy. All the Young Queers an absolute joy to read! " – Kathy Hoyle "An astonishingly accomplished range of stories, beautifully written, taking in everything from first love to chemsex, set in the recent past, among the hallowed walls of academia and even in other worlds. Tales steeped in nostalgia, politics and a groundswell of change. A masterful blending of periods, politics and formats, including stories written in text messages and court documents. I laughed, I cried, I nodded my head in recognition. I felt seen." – Iqbal Hussain "An enchanting romance—funny, touching and inspiring." – Stephen Fry on One Last Song "It's very funny, very touching and has the absolute ring of truth about it. One can't but fall in love with these two more or less impossible people, as they fall in love with each other." – Simon Callow on One Last Song "Adored this book and couldn't put it down. An unapologetically queer love story set in a care home. Touching. Heartwarming. Funny. Sad. Beautifully drawn characters I wanted to spend more time with. It was over too quickly for me. Joan and Jim, and their burgeoning relationship will stay with me for a long time. I loved it." – Jonathan Harvey on One Last Song "One Last Song is a necessary love story, both profoundly moving and profoundly optimistic. It will inevitably infiltrate your heart." – Martin Sherman "A warm, joyful and ingenious tale of gay love from the UK's Armistead Maupin." – Joelle Taylor on One Last Song "When we forget our gay elders and the radical queer people who lived so we could fly, we forget ourselves. Nathan Evans has not just remembered these elder angels, he has painted them with humour, love, truth and glory. This is a gem of a novella with characters to cherish." – Adam Zmith on One Last Song "One Last Song is a beautiful, smouldering, hilarious and sparkling testament to queer intimacy and the revolutionary potency of queer creative activism. Every page filled my heart with Pride." – Dan Glass "One Last Song is edgy, funny and moving. A heady mix that packs an emotional punch.' – Paul McVeigh "Touching, powerful, punchy, funny and sweet. An absolute delight." – David Shannon on One Last Song

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 164

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

3

Praise for All the Young Queers

‘original, compelling and cleverly crafted’

JON RANSOM

‘A wonderful collection of bildungsroman stories, full of vibrant characters finding their place in a jaded world. Evans beautifully captures the steep learning curve of each young protagonist—characters who must traverse religious, social, political and sexual dilemmas in order to discover who they really are. Evans is not afraid to play with voice and structure, making this a smart, insightful collection, where every story sparkles with rich, engaging prose and the perfect balance of humour and poignancy. All the Young Queers is an absolute joy to read!’

KATHY HOYLE

‘An astonishingly accomplished range of stories, beautifully written, taking in everything from first love to chemsex, set in the recent past, among the hallowed walls of academia and even in other worlds. Tales steeped in nostalgia, politics and a groundswell of change. A masterful blending of periods, politics and formats, including stories written in text messages and court documents. I laughed, I cried, I nodded my head in recognition. I felt seen.’

IQBAL HUSSAIN4

5

Praise for One Last Song

‘An enchanting romance—funny, touching and inspiring’

STEPHEN FRY

‘It’s very funny, very touching and has the absolute ring of truth about it. One can’t but fall in love with these two more or less impossible people, as they fall in love with each other.’

SIMON CALLOW

‘Adored this book and couldn’t put it down. An unapologetically queer love story set in a care home. Touching. Heartwarming. Funny. Sad. Beautifully drawn characters I wanted to spend more time with. It was over too quickly for me. Joan and Jim, and their burgeoning relationship will stay with me for a long time. I loved it.’

JONATHAN HARVEY

‘One Last Song is a necessary love story, both profoundly moving and profoundly optimistic. It will almost inevitably infiltrate your heart.’

MARTIN SHERMAN

‘A warm, joyful and ingenious tale of gay love from the UK’s Armistead Maupin.’

JOELLE TAYLOR

‘When we forget our gay elders and the radical queer people who lived so we could fly, we forget ourselves. Nathan Evans has not just remembered these elder angels, he has painted them with humour, love, truth and glory. This is a gem of a novella.’

ADAM ZMITH

‘One Last Song is a beautiful, smouldering, hilarious and sparkling testament to queer intimacy and the revolutionary potency of queer creative activism. Every page filled my heart with Pride.’

DAN GLASS6

7

9

for Justin for encouraging me to try my hand at fiction for everything

10

Contents

13

14

16

Glass House

‘Shouldn’t have that on this time of morning,’ Mum says as she barges in without knocking. ‘Cost a fortune.’

‘Bank holiday,’ I say. ‘Cheap rate.’ And I lean in to cover the computer screen as she strides across the room to fling the airing cupboard open. So annoying. When they built the extension, the boiler ended up in my room for some reason. ‘What time you leaving?’

‘Soon. First race is at ten.’

She grabs three pairs of freshly-aired trainers—three different colours, same stupid tick—then races off downstairs again, calling, ‘You finished those sandwiches, Ian?’

She’s left the door wide open. I sigh and shut it after her, then go back to the website for a last-minute check.

Is it today?

Yes. May the first.

And do I know where?

Yes. London A-to-Z. Pocket of my army trousers.

Turn off the computer. Go downstairs. In the living room, David is watching television—wearing matching trainers and tracksuit bottoms. In the dining room, Mum is torturing her hair before the mirror. In the kitchen, Dad is spreading sliced wheatgerm with margarine. He has to shout over the drone of Mum’s dryer.

‘What time’s your train?’

‘Quarter to ten.’

‘Want a lift to the station?’

‘It’s alright. I’ll walk.’ 16

I sit eating cereal, drinking tea as sandwiches are packed into boxes, boxes into bags, and bags into the boot of the car.

At the front door, Mum hands me a fiver.

‘Get yourself a McDonald’s.’

‘No thanks.’

‘Something vegetarian then!’

In the driver’s seat, Dad starts the engine. In the backseat, David sticks out his tongue. In the passenger seat, Mum belts up and belts out, ‘You be back by seven!’

‘Yes, Mum!’

‘And don’t do anything I wouldn’t!’

Her door slams shut, and they’re off. Up the road and round the corner. I hold my breath and listen for the last of the motor. Then grab my bag and head out the back door.

The greenhouse is at the top of the garden. Dad grows cucumbers in summer, but it’s mine the rest of the year. I open my bag and, one by one, place the pots inside.

I’m ready to leave by nine-fifteen. Make a last check I’ve got everything.

Money. Key. Pen. Water, sandwiches. Ventolin.

I’ve never been to London on my own. But now I’m sixteen, Mum says I can. I have been with school to see the National Gallery. That’s where she thinks I’m going today.

Westminster station is surrounded by police. I try not to make eye contact as I exit, and join the crowd reclaiming the street.

Some are carrying flowers. One or two with wheelbarrows. A woman wearing face paint hands me a leaflet. Guerrilla Gardening! Mayday Action! I’m in the right place, then. The leaflet explains that—should the police get me—I have the right to remain silent and should consult a lawyer before saying anything. 17There’s a number at the bottom.

Look up. See a woman climbing a lamp post. And over there, there’s another one. Something is swinging on a rope between them. It’s a banner. It says Let London Sprout.

Fucking brilliant.

Someone’s put a maypole up. Kids are dancing round it. Someone else has put grass down in the street. They’re having a picnic. And there’s a strip of grass on this statue’s bald head. Looks like a mohican.

Fucking brilliant.

Wander to the centre of the square. The earth feels lumpy beneath my feet. They must have laid turf in the night. But now, they’re digging it up and putting in plants. I try not to tread on any of them. Some look like they’ve already been stood on. Others are wilting in the sunshine. The website said bring water. Looks like no one bothered. I brought two litres. This bag’s killing my shoulder.

I stop in the corner and put it down. I look around. The website said form groups. I kind of assumed it would just happen.

Realise I don’t know anyone.

‘Window shoppers not welcome.’

He’s about the same age as me. Bit older maybe. Mohican, like the statue—except his is blue—and a ring through his eyebrow. He’s pulling up flowers with his fingernails.

‘Sorry, what did you say again?’

‘Fuck off or give us a hand.’

He turns back to his tulips. I find my fork and join him in the flowerbed.

‘I’m Jason.’

He nods. ‘Bod.’ 18

I’ve never met a Bod before. ‘Why are you pulling up plants that’re already here?’

‘Liberating them.’

‘What from?’

‘Borders are a form of fascist oppression.’

He starts ripping up grass—with only his fingers, hard work. I lend him the fork, then carefully manoeuvre a cutting between my bag’s zipper.

‘Does it matter where?’

‘You mean you don’t have permission?’

‘Do I have to get…’

He laughs. ‘Wherever you like, man.’

Feel stupid. Start digging. ‘What are they filming?’

‘Who?’

‘The policemen.’ They’ve got cameras—those little digital ones.

‘Us. Fucking perverts.’

I hide behind my hair. Give my plants water. Try to make them stand straighter. Bod has finished. His are lopsided.

‘Very nice,’ he says. ‘You want some of this?’

I had a joint once. When Trevor’s parents went away the weekend. Didn’t really do anything. I’m asthmatic. I’m not very good at inhaling.

‘Alright then.’ I check no-one’s looking and take it from him.

‘Been on one of these before?’ He lolls back. And his System of a Down t-shirt rides up.

‘No. You?’ I try not to look at his belly fluff.

‘Yeah. See those riots last year? I was there. Fucking give the pigs what for.’

I try not to cough.

How embarrassing.

I try again. 19

I’m laid back on the grass watching clouds floating past when I notice a woman stood over us.

‘Give us a drag, Bod.’

She’s older than we are, hair laced with shells and silver. Bod passes the joint over.

‘Jason, this is Maya.’

She smiles in my direction. ‘Some great stuff going down.’

‘Mm.’ I seem to be grinning.

‘You come on your own?’

‘Mm.’ I seem to be unable to formulate a sentence.

‘Aw…’

I turn to the sky again. Try to focus on something but the clouds keep moving.

‘Fucking brilliant man!’ A guy with blond dreads looms into vision. ‘Someone smashed the McDonald’s in.’

Bod says, ‘Where?’

Dreads says, ‘Trafalgar Square.’

Bod says, ‘I’m there.’

He jumps up. ‘Coming?’

I realise he’s looking in my direction.

There’s this statue on which someone has written men’s toilet. Bod laughs and takes advantage. We notice some policemen and run. I try not to notice Bod’s dick, still dangling from his zip. He shouts, ‘Fucking pigs!’

There’s this sea of heads and Nelson’s Column in the middle. Bod tries to push through but there’s too many people. ‘Fuck this.’ He pulls me into a side street.

There’s this row of police vans and policemen piling from them. They’re wearing masks. They’ve got shields on their arms. 20

And then they’re stood between us and Trafalgar Square. On this side are protesters. On that side are protesters. The police keep piling in, hundreds of them, forming lines behind the front one. I don’t understand what’s going on.

‘Why do they have to spoil everything?’

‘Because they’re fucking pigs.’

When we work out the police are letting in tourists, we squeeze past, pretending not to speak English. Inside the square, it’s emptier than expected. And strangely silent.

There’s the police.

And then there’s us.

Now what?

I notice the sun has gone in. Then I hear something smashing and a woman screaming. She’s got a baby in a pushchair. She shouts, ‘Keep together, keep together!’ as her other kids run after her.

Bod’s laughing. He’s got a bottle in his hand. He says, ‘Your turn.’

His eyes are blue as his mohican. My heart stops beating. I look down to see my hand take the bottle from him.

I’ve never been good at throwing. I don’t expect to hit anything.

The policeman just keeps staring, staring as splinters fall around him.

I stand waiting for the earth to open. It doesn’t.

Fucking pig.

I’m addicted.

When the police start moving in, we run—back out the way we came.

Bod pulls up out of breath. ‘I need a drink.’ 21

I offer what’s left of my water. He shakes his head.

‘There’s this party at Maya’s—you wanna come?’

‘Should be going—said I’d be home by seven.’

Fuck. Did I really just say that?

His eyebrow ring rides up a bit.

Now I’ve really blown it.

‘You got a number? Be back in London again soon.’

Not got any paper, so he writes on my travel card. I say I’ll call him maybe next week, and watch his blue fin dipping in and out of vision along the crowded street.

When I get home, they’re all watching television.

Dad says, ‘Didn’t want a lift then?’

And Mum, ‘Best put your own dinner in the oven.’

Marks and Spencer’s vegetarian lasagne. Still eating when she calls through to the kitchen. ‘You see this, Jason? Been a riot in London.’

I hear the reporter from outside the living room door, ‘… defacing a statue of Winston Churchill before proceeding up Whitehall…’

Mum says, ‘Innit terrible?’

My heart beats triple-time as I step in.

‘…the Cenotaph was desecrated…’

I loiter behind the sofa, staring at the screen over their shoulders.

‘…a branch of McDonald’s vandalised…’

It’s not the same protest at all. There’s no plants. No maypoles. Just pixelated pictures of smashed windows.

‘…the National Gallery forced to shut…’

Mum says, ‘Isn’t that where you went?’

‘Must have been after I left.’ 22

But the screen contradicts. Because there I am. And there’s the bottle, leaving my hand.

David stares from his armchair. The silence from the sofa lasts forever. Or at least until broken by the news reporter.

‘…police are requesting that viewers who recognise any protesters please call the number now appearing on your screen…’

She says, ‘Pass me the phone, Ian.’

‘What’re you doing?’

‘That wasn’t why you were let go to London.’

‘But, but…’ My hard drive is struggling to start up. ‘It wasn’t like that!’

‘Like what?’

‘It was the police’s fault.’

Her eyebrows knit, like she can’t compute this. ‘Don’t be ridiculous!’

‘Everything was fine until they came along.’

She says, ‘Ian, will you pass me the phone.’

He says, ‘Your great-grandfather died in that war.’

‘What war?’

‘World War Two. They teach you anything at that school?’

‘So?’ I centimetre towards the door.

‘The Cenotaph. Do you know what it’s for? It’s for all the soldiers who died, yeah? And without those men, you wouldn’t even be here,’ he says as he picks up the receiver.

I run. Out the front door and onto the street. He runs after. ‘Get back here!’

He’s faster. But he’s wearing slippers. One of them falls off. He has to stop.

I stop around the corner.

Fuck! What if he comes after me in the car?23

Keep running. Can’t see for sweating.

What am I gonna do?

My fingers find a solution, as they scramble in my pocket for a tissue.

07700900312.

Take a breath. Insert ten pence.

I’m in the call box outside Chatham station. Checking out the window that Dad isn’t coming. Take travelcard from pocket. Dial number on it. Look at my watch. There’s a train in two minutes. If he answers now I might just catch it.

‘Hello?’ It’s him.

‘Bod, it’s Jason. I was wondering…’

He’s hung up.

No. It’s a fucking mobile. The fucking money’s run out.

No change. No time to get more. Got to get the train now or wait another hour.

Arrive on the platform as the train’s pulling in. No time for the ticket machine. All the way back to London, I’m praying the inspector doesn’t come.

He doesn’t.

Victoria Station. My last tenner. Buy a Mars bar. Line up the change on top of the phone.

‘Hello?’

‘Bod, it’s Jason.’

‘Who?’

‘Jason!’ Have to shout. Music blaring in the background. ‘We met this afternoon?’

‘Yeah, man. How’s it going?’

‘Alright, I…’ Another twenty. ‘You at the party?’ 24

‘Fuck man. Don’t know where I am.’

Another ten. ‘You said I could come?’

‘Do what you like, man.’

And another one. ‘Well, where is it then?’

‘Brixton.’

Seconds left. ‘But what’s the address?’

‘Acre Lane.’

It’s beeping. ‘What number?’

‘Fifty-nine.’

Brixton is on the Victoria line. Still got my travel card. Still got my A to Z. Pocket of my army trousers. On the underground, I memorise directions. Left out the station, right at the junction.

Brixton is full-on. Busy as the protest this morning.

Left out the station.

And like this morning, I keep my head down.

Right at the junction.

Acre Lane. Can hear the music. Number fifty-nine.

Front garden’s a state. Front door’s flaking paint. I knock on it.

Nothing.

Knock louder.

It opens.

‘Hello, dear.’ It’s Maya. ‘Wasn’t expecting to see you here.’

‘Neither was I.’ Feel blood draining into my Dms. ‘Is it okay?’

‘Course!’ She folds me into the tie-dye she’s wearing. ‘Come in.’

Mum would say she needs a good washing. ‘You want a beer or something?’

I take the bottle from her hand.

Not throwing this one.25

‘Bod!’

He’s sprawling in a pile of cushions. I have to dodge dancers to reach him.

‘Bod?’

He looks up. His eyes take a long, long moment to focus. He nods.

I sit down. Justify my presence in the room.

‘Had to come.’

He’s rolling another joint. Doesn’t look like he needs it.

‘My parents went ballistic—you see it?’

He lights up. ‘What?’

‘The news report.’

‘No man. You give us a blowback?’

‘A what?’

He laughs. ‘Come closer and I’ll show ya…’

His eyes are rings of blue, floating in pink pools. They point in my direction but he isn’t really looking, isn’t really seeing.

‘Fucking brilliant.’

The weed is all he’s taking in.

Suddenly the music stops. The guy with dreads who came running over in the square has turned on the television in the corner. It’s a repeat of the report from earlier. And there I am. I made it to the headlines.

‘Let me shake your hand, man.’ A big guy with a beard slaps me on the back and crushes my fingers. ‘Welcome to the revolution.’

Someone cheers. I smile. Turn to Bod. Bod isn’t interested.

‘Totally fucking misrepresented.’ Dreads is pacing. ‘They twist and turn everything to their own ends.’

‘That’s because we’re a threat,’ says a guy with a hat. ‘They 26feel threatened because we see through their fucking system.’

‘Too fucking right, man.’

For the first time, they’re showing pictures of the Parliament Square planting. I ask, ‘Who put the grass down?’

‘Fucking Parliament, I expect.’

‘But it was lumpy.’

‘Can’t trust that lot to do anything properly.’

I frown. ‘We were digging up real grass then?’

Beard laughs. ‘Wish it had been.’

‘But…’ I hesitate. ‘What’s the point in that?’

He pulls a packet of Marlboro from his pocket. ‘It’s symbolic.’

‘Of what?’

‘What do you mean?’

‘It can’t just be symbolic. It’s got to be symbolic of something.’

Not sure where this is coming from.

‘Fucking lost me, man.’

‘Well, what about the Cenotaph?’ They’re showing it on TV. ‘Isn’t that symbolic?’

Dreads grabs for his crotch. ‘It is now I’ve anointed it.’

I avert my eyes to the floor. He’s got Nike trainers. Same colour Dad wears.

And when I open my mouth, Dad’s voice comes out. ‘My great-grandfather died in that war.’

Hat swigs from a can of Coca-Cola. ‘Listen man, I’m sorry about your grandpa and everything, but you gotta understand that war is just another form of capitalist exploitation.’

‘Without that war, we’d be living in a world ruled over by Hitler.’

Dreads says, ‘Couldn’t be any worse than Tony Blair.’

‘Don’t be ridiculous.’

And now my mother.27

‘Who let this little cunt in here?’

Bod says, ‘Fucking followed me here. Fucking queer.’

The room goes silent. I sit frozen. Daren’t turn my head in either direction. In the corner of one eye, I see bastard Bod. His blue mohican bobbing as the beat drops back in. Bastard Bod. Bod the Bastard. Bobbing, bobbing.

I get up and go out to the garden. Down to the bottom. It’s dark and it’s quiet. Smells like my greenhouse. Take deep breaths. Take it out on a tree trunk. Imagine it’s him.

And then I’m crying.

‘You alright?’

It’s Maya. Can just about see her.

‘I’m fine.’ Hope she can’t make out my tears.

‘Why don’t you go home, dear?’ She squeezes my shoulder. ‘Bit out of your depth here.’

‘I can’t…’ And then I’m tearing up again and telling her how my parents have turned me in. She takes me in her arms, and I don’t even care about her smelling.

‘Why don’t you let me ring them and tell them you’re safe and you’ll see them in the morning?’

‘But where will I sleep, then?’

‘Well, it’s a nice evening…’

Don’t know what she says to them. I stay out in the garden.

She brings blankets and cushions. I lay looking at the moon.