Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Inkandescent

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

When a gentleman called Joan lands up in a care home, Jim doesn't know what's hit him—everything about his new neighbour is triggering. And Joan is a colourful, combustible cocktail—ticking. Battle begins. May the best man win. But beneath antics and antique armour plating, what are both hiding? And maybe they just may be batting for the same team. An uproarious and uplifting romantic comedy about grey liberation. "An enchanting romance - funny, touching and inspiring" — STEPHEN FRY "It's very funny, very touching and has the absolute ring of truth about it. One can't but fall in love with these two more or less impossible people, as they fall in love with each other." — SIMON CALLOW > "A warm, joyful and ingenious tale of gay love from the UK's Armistead Maupin." — JOELLE TAYLOR "I adored this book. Touching. Heartwarming. Funny. Sad. Beautifully drawn characters I wanted to spend more time with…" — JONATHAN HARVEY "When we forget our gay elders and the radical queer people who lived so we could fly, we forget ourselves. Nathan Evans has not just remembered these elder angels, he has painted them with humour, love, truth and glory. This is a gem of a novella with characters to cherish." — ADAM ZMITH "One Last Song is a beautiful, smouldering, hilarious and sparkling testament to queer intimacy and the revolutionary potency of queer creative activism. Every page filled my heart with Pride." — DAN GLASS "One Last Song is edgy, funny and moving. A heady mix that packs an emotional punch." — PAUL MCVEIGH "Touching, powerful, punchy, funny and sweet. An absolute delight." — DAVID SHANNON "One Last Song is a necessary love story, both profoundly moving and profoundly optimistic. It will almost inevitably infiltrate your heart." – MARTIN SHERMAN Nathan says, "The fight for gay rights began in the sixties; some of its original warriors are now in their seventies and eighties, facing new battles with infirmity and isolation. This story is for them. I first told it in screenplay: it attracted the attachment of Simon Callow and Richard Wilson, but insufficient investment. I then told it as stage play: it attracted Arts Council funding (and rave reviews) for a site-specific performance at the legendary RVT, for one-night-only. It's a story that's always needed a wider audience. A story that remains un(der)told. Queer love in the care home? Here it comes in novel form."

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 210

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

ONE LAST SONG

Table of Contents

Title Page

BIOGRAPHY

Praise for One Last Song

Praise for SwanSong

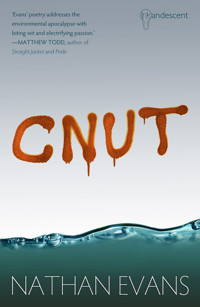

Praise for CNUT

Praise for Threads

ONE LAST SONG | Nathan Evans

ONE LAST SONG

JOAN

JIM

JOAN

JIM

JOAN

JIM

JOAN

JIM

JOAN

JIM

JOAN

JIM

JOAN

JIM

JOAN

JIM

JOAN

JIM

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Also from Inkandescent

BIOGRAPHY

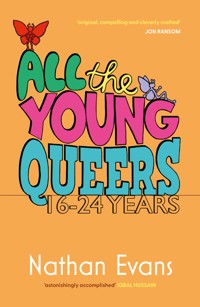

NATHAN EVANS is a writer and performer based in London. Publishers of his poetry include Royal Society of Literature, Fourteen Poems, Broken Sleep, Dead Ink, Impossible Archetype and Manchester Metropolitan University; his debut collection Threads—a collaboration with photographer Justin David—was long-listed for the Polari First Book Prize 2017, his second collection CNUT is published by Inkandescent. Publishers of his short fiction include Untitled, Queerlings and Muswell Press; One Last Song is his debut work of long-form fiction.

Nathan’s work in theatre and film has been funded by Arts Council England, toured with the British Council, archived in the British Film Institute, broadcast on Channel 4 and presented at venues including Royal Festival Hall and Royal Vauxhall Tavern. He hosts BOLD Queer Poetry Soirée, and has chaired/hosted events for National Poetry Library, Charleston Small Wonder Festival, Stoke Newington Literary Festival and Rye Arts Festival; he teaches on the BA Creative Writing and English Literature at London Metropolitan University, and is editor at Inkandescent.

www.nathanevans.co.uk

Inkandescent Publishing was created in 2016

by Justin David and Nathan Evans to shine a light on

diverse and distinctive voices.

––––––––

Sign up to our mailing list to stay informed

about future releases:

––––––––

MAILING LIST

––––––––

follow us on Facebook:

@InkandescentPublishing

––––––––

on Twitter:

@InkandescentUK

––––––––

on Threads:

@inkandescentuk

––––––––

and on Instagram:

@inkandescentuk

Praise for One Last Song

‘An enchanting romance—funny, touching and inspiring’

STEPHEN FRY

––––––––

‘It’s very funny, very touching and has the absolute ring of truth about it. One can’t but fall in love with these two more or less impossible people, as they fall in love with each other.’

SIMON CALLOW

––––––––

‘Adored this book and couldn’t put it down. An unapologetically queer love story set in a care home. Touching. Heartwarming. Funny. Sad. Beautifully drawn characters I wanted to spend more time with. It was over too quickly for me. Joan and Jim, and their burgeoning relationship will stay with me for a long time. I loved it.’

JONATHAN HARVEY

––––––––

‘One Last Song is a necessary love story, both profoundly moving and profoundly optimistic. It will almost inevitably infiltrate your heart.’

MARTIN SHERMAN

––––––––

‘A warm, joyful and ingenious tale of gay love from the UK’s Armistead Maupin.’

JOELLE TAYLOR

––––––––

‘When we forget our gay elders and the radical queer people who lived so we could fly, we forget ourselves. Nathan Evans has not just remembered these elder angels, he has painted them with humour, love, truth and glory. This is a gem of a novella.’

ADAM ZMITH

––––––––

‘One Last Song is a beautiful, smouldering, hilarious and sparkling testament to queer intimacy and the revolutionary potency of queer creative activism. Every page filled my heart with Pride.’

DAN GLASS

––––––––

‘One Last Song is edgy, funny and moving. A heady mix that packs an emotional punch.’

PAUL MCVEIGH

––––––––

‘Touching, powerful, punchy, funny and sweet. An absolute delight.’

DAVID SHANNON

Praise for SwanSong

‘Side-splittingly funny and achingly romantic. A play about ageing disgracefully that’s ferociously full of life.’

RIKKI BEADLE-BLAIR

Praise for CNUT

‘CNUT is a kaleidoscopic journey through shifting landscapes, brimming with vivid imagery, playfulness and warmth. A truly powerful work!’

KEITH JARRETT

––––––––

‘Evans’ poetry addresses vital issues of our time, such as the environmental apocalypse, with biting wit, seething passion and electrifying skill.’

MATTHEW TODD

––––––––

‘Story weaving and poetically burrowing, CNUT is a universal backyard collection of the urban/urbane reimagined, of the domestic/fantastic retold, of the ravishingly re-readable.’

GERRY POTTER

––––––––

‘Poignant, humane and uncompromising’

STEPHEN MORRISON-BURKE

Praise for Threads

‘In this bright and beautiful collaboration, poetry and photography join hands, creating sharp new ways to picture our lives and loves.’

NEIL BARTLETT

––––––––

‘A poetic, performative landscape where the everyday bumps up against memories, dreams and magic.’

MARISA CARNESKY

––––––––

‘A winning blend of words and images, woven together with passion and wit.’

PAUL BURSTON

First published in the UK by Inkandescent, 2024

––––––––

Text Copyright © 2024 Nathan Evans

Cover Design Copyright © 2024 Justin David

Artwork Copyright © 2024 Nathan Evans

––––––––

Nathan Evans has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the author of this work.

––––––––

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

––––––––

This book is a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

––––––––

While every precaution has been taken in the preparation of this book, the publisher assumes no responsibilities for errors or omissions, or for damages resulting from the information contained herein.

––––––––

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-912620-28-9 (paperback)

ISBN 978-1-912620-29-6 (ebook)

ISBN 978-1-912620-30-2 (audiobook)

––––––––

www.inkandescent.co.uk

ONE LAST SONG

Nathan Evans

for Winifred Baker, in St John’s Home

still living in spectrum

ONE LAST SONG

JOAN

Well, get her! Hair to shoulder, legs forever, precipitous platforms and a placard proclaiming Gay Liberation.

Of course, my hair was hennaed. Can’t tell from this picture. Black and white. Grey really, beneath the patina of soot. I give it a wipe, take a better look. And what a looker I was. Not that I could see it then. That jawline, that denim—looks like it’s been painted on. Must’ve been, what... seventy-one? No. Seventy-two. The first London Pride demonstration. When it was still a demonstration. When I was still a young man.

The honk of a horn disturbs my contemplation; these old eyes take their time adjusting: my long distance is shocking. Fortunately, this room is not a large one, and I have never been a size-queen.

‘He’s here!’

Gladys—née Gareth—steps into focus, buttoning a salmon-pink blazer. ‘I’m going down.’ Not the first time she’s used that line, I’m certain. ‘Now, put that photograph back where it came from.’ Gladys has always liked to take control of a situation. Except in the bedroom. ‘And do make sure you’ve got everything—there’s no coming back if you forget something this time, Joan.’

She swooshes her scarf over shoulder, as if exiting some antique drawing room drama; I pull my face up as she pulls the door shut, then put the photo back in the box where I found it. She’s right, of course; I am forgetful these days. I’ve been known to leave the house without my keys, my dignity. And poor Gladys has picked up the pieces. So I shouldn’t bitch—she’s my last friend left. More cocks up her than she’s had hot dinners, but somehow it never got her. It got all the others.

Oh dear. I promised no tears. But it’s overwhelming, all of a sudden, all alone in this room. A room that’s been home half a lifetime—like me, long past its prime. Almost forty years, I have lived alongside this furniture. And the scenes it has seen! The men! The conflagrations.

Well, that was it for the housing association. Dozy mare—dosing off whilst partaking of marijuana nightcap. Caught one of the throws and up it went in smoke. I came to, thinking I was in Heaven, dry-ice swirling, and lay, waiting, for ‘Disco Inferno’ to kick in. But no, my clubbing days are done; it was only the neighbours calling 999 that saved this old gammon.

So now it’s been deemed I require around the clock attention. Previously there was a sporadic succession of thin-lipped women trained by Stalin. Making certain I was eating properly. Tying my shoelaces. Authority is never something to which I’ve responded positively—tell me to do anything, and I shall likely take an equal and opposite course of action. Got me thrown out of home at fifteen. It’s getting me thrown out again.

There’s the stairs. Footsteps, two pairs. Better pull myself together. As I always have done. When Michael died. And Martin. When I got arrested that time.

My slacks are cerulean, belt and braces tightened. My shirt, cerise chiffon—could use an iron. So too this saggy skin. I put on the best face I can, cap it with my bestest yolk-yellow bonnet. My appearance arrests in-track the disappointingly portly gentleman for whom Gladys holds the door open. I assay a curtsey as I greet him. ‘And you must be the porter, I presume?’

If he has a name, he doesn’t give one. Probably just as well as I would only have forgotten it by the time he’d taken one box and returned for the next. There are quite a number of them, piled and packed with what remains of my earthly possessions. They’ve been somewhat strict about volume and contents. Regulations I took some satisfaction in flouting. The inferno, though, has made editing easier. My name is Joan, and I am a hoarder. Comes from a childhood of going without, my dear. Imagine—seven of us in one rented accommodation! And this is before London’s East End became glittering. Now it’s all organic whatnots and shoes with no socks.

Thankfully, my footwear withstood the fiery flames—I favour a sensible flat, these days. Also withstanding, my prize possession—the record collection, sitting ready-to-porter. I can’t help thinking they might have sent someone dishier for my big closing number. Donkey-featured and -footed, he trudges in and out, out and in—Gladys flapping around him like she’s conducting. Likes to feel useful since she took the retirement, even offers to lift something. He fortuitously declines. At our great age, exertion must be undertaken with precaution. Pull something and you’ll be pushing up the daisies in no time.

Though Gladys is but a chicken—been a good decade since I took the retirement. ‘All ready, Joan?’

And then there was one. One old bag to be taken down. No, thank you, I do not need a hand. I shall take this curtain alone. Though I may take some time.

The building is even more ancient than I am—crumbling cornicing, busted banisters and, of course, no elevator. I swear they’ve added a stair for every year I’ve been here, and by the time I reach the bottom, I’m rasping like I climbed a mountain.

I rally and sally into Notting Hill sunshine.

It’s not always been home to the starlets and oligarchs; I blame Julia Roberts. When I moved in, W11 was one of the less desirable postcodes in town; then came that dreadful film. I expect the council will sell the flat for a tidy profit. Line their Tory pockets. No wonder they want me out of it.

On the street, Gladys is hand-wringing and a minibus is awaiting. Well, they might have sent the limousine. My boxes are all waiting within, and Mister Porter is huffing and puffing with his access ramp down. I don’t think so, darling. This queen ain’t going in the back of no bus yet: I opt for the passenger seat.

It’s somewhat further off the ground than I’d imagined. And it is something of a struggle to get the seatbelt fastened. But Gladys, dearest Gladys, comes to my assistance—lets her hand rest on mine a moment too long. I know something is coming. ‘Now, John...’

She cannot have called me by that name since about 1971; we were all feminising ourselves back then. Gareth became Gladys, John became Joan; we began experimenting with make-up and clothing. Most men moved on as glam gave way to disco then punk but, for me, it became a mission—my name and my appearance a card thrust into the world’s hand, proclaiming revolution. I was not neither one thing nor the other thing—I was everything at the same time. I was a man who chose to take a woman’s name. I was a man who chose to wear both masculine and feminine clothing, finding ludicrous the very notion that cloth cut and stitched in a certain fashion could somehow be ‘gendered’. It was my clothing, if I was wearing it. It was my name, if I was using it. That Gladys has chosen to name-peel—as only she has the privilege to do—can only signal she’s about to get real.

‘Do try to get on.’ The eyebrows arch in formation: I have form when it comes to neighbourly vexation. With a purse of the lips, I signal I too have been vexed; Mister Porter-cum-Driver signals impatience by starting his engine. Gladys’ head is shaking. ‘I’ll come see you soon.’ She seals my fate with a slam, stands weeping and waving on the pavement.

As the bus pulls off, I do not look back, lest I be turned into a pillar of salt. They might also have put more thought into my exit music. Mozart. Or Wagner, perhaps. Mister Driver is playing some nondescript thump-tchk thump-tchk. And just at this moment, I can’t find the strength to ask him to change it.

In these sorts of situations, there’s one thing that always makes me feel better. I flip down the overhead mirror. Oh dear. That mascara’s not as waterproof as the packaging promised. I have a damage-limitation dab at the corner of each eyelid, notice the nail polish is already chipped. Oh dear, oh dear. I reach into the handbag on my lap, pull out my Rouge Allure. Roll it up like a dog-dick.

Knuckles go white on the gear stick.

I’ve always enjoyed a scene. Making up on the bus. Making a fuss. As I make the pout, lips reddened, I catch the driver’s reflection in the rear-view mirror, staring. Let Operation Shock and Awe begin.

JIM

He is sitting in his usual chair, its arms worn by others who have sat there, squinting down at his hand, mottled and veined; the hands of his watch tell him it is 3.54pm. He has a book in his other hand. He has been reading the same sentence for some time: its meaning still escapes him. A cloud is in the sky, surely. A cookie is taken with tea.

He reaches for an English Breakfast. His mug—classic, ceramic—is a reminder of home. Its contents have gone cold. The contents of his home? He will return to them soon.

Returning tea to coffee-table, he is aware of someone watching him across the laminated length of the thing. He adjusts his glasses, eyes adjusting with difficulty to this new focal distance. He will get them tested again when he gets home. He makes out that woman. What is her name? She must be in her eighties; her dress cannot have been fashionable since that decade. She is always making eyes at him. In a way he has not seen since the playground. Or perhaps the office, when they had first recruited him.

Seeing herself seen, she looks down towards the man in uniform—blue tunic, brown skin and hair an incongruous blond. Whatever his name is, Jim cannot recall, and the letters on his badge are inscrutably small. He is kneeling on linoleum flooring and painting the woman’s toenails. He is painting them some godawful shade of purple.

The polish assails Jim’s nostrils. There is nothing wrong with his sense of smell. He is reminded of pear drops, always his least favourite pick ‘n’ mix. And of the girls in the office; they would change nail-colour in their lunch-hour as they whispered together.

The woman-in-purple whispers into the man-in-uniform’s ear. ‘Do you think he is, then?’

Jim’s hearing is also still sharp as a pin.

The man-in-uniform looks up at him, smiling. ‘What you studying, Jim?’ He speaks in that manner they all use with him: like he is a child again.

Jim maintains a dignified silence, returns to his instruction: it is important to keep up with developments if one is to get a position. At this rate, he will never find employment. His eyes slide from the writing like a man down a sheer glass building. Like the ones he built, will build again. If he can ever get his head around this internet thing.

‘I know when a man’s interested.’ The woman-in-purple whispers again. ‘Got through ‘em like a dose of salts, I did.’

Peering over the parapet of his pages again, Jim sees she is now flirting with the man-in-uniform. She must be three times his age. It is quite obscene. Though Jim supposes he can see the attraction. The man keeps himself trim. As Jim has always done. Racket sports are his thing: out on the court on one’s own, creating invisible structural models with the movements of one’s arm. And then, the winning. By now, his trophies must need dusting. Never too late to add to them, he wonders if South Kensington squash club still meets on Wednesday evenings. He will enquire about re-joining. Just as soon as he is on his feet again.

‘That why you got your best frock on?’ The man-in-uniform has deftly driven the woman-in-purple’s attentions to the arrival of a new man. Arrivals are always a cause of excitement. Especially the arrivals of men. There are currently only two of them on the men’s side of the room: Jim and the Nigerian. Or perhaps he is Jamaican. Jim has never dreamt of asking.

‘Eighteen down.’ The other man is doing something Jim will never do: he is muttering to himself whilst completing a crossword puzzle and, though there is an empty chair between them, Jim can easily hear him. ‘Not on either side. Seven.’

Neutral, thinks Jim. But does not deign to say anything. He does not dig foundations; he will not be here long. He keeps his business to himself. And, indeed, his photographs. The other man has spawned snapshots all along the mock-wood mantlepiece—varicoloured grandchildren in varicoloured costumes, who never come to visit him.

The woman in the dressing gown—the one whose needles are constantly clicking—her offspring, on the other hand, never stop visiting. On a Sunday morning, she sits terrorised amongst all their ill-mannered children. She is now knitting booties for another of them. Lemon. Yesterday—or was it the day before—the woman-in-purple spent some hours setting down the correct attribution of wool-colour to gender. Blue for a boy. Pink for a girl. Lemon for everything in between. Apparently, the gender of this latest arrival is yet to be determined.

The woman-in-purple takes great interest in other people’s grandchildren, having none of her own. She constantly bemoans her daughter’s lack of a man. And lack of visitations. The woman-in-dressing-gown, poor thing, just sits there mmming.

That will never happen to Jim. He will never sit in worn pyjamas in a worn armchair. Every morning he gets dressed for the office and combs what remains of his hair. Every morning he scours the job section of the newspaper—as soon as he is out there, out of this retirement he cannot bear, the better. Proven ability to interpret legislation and implement policy. Tick. Proven line management and excellent IT... Damn it. Back to that damn book. Getting Online (when you’re Getting On). Or something along those lines...

He is startled by a handclap. He must have dozed off. He must stop doing that. The boss woman is stood in the doorway, hands pressed together before her. She reminds Jim of his first teacher, Mrs Blackburn. Though she never wore one of those headscarf things.

‘Everyone. I would like to introduce our new resident.’

The woman-in-purple sits up in her chair, checks her hair. It is thinning, her roots re-growing. She is cooing and fluttering in anticipation of a new man. Another figure steps into focus beside boss-woman. It cannot be described as a man. Or a woman. The figure does not appear to conform to either gender. It is wearing one of those hats—floral, full-brimmed—like Jim’s mother used to wear to weddings. It is wearing pearlescent earrings. It is wearing lipstick. Crimson. It is wearing stubble upon its chin. And a ghastly confection of clothing, masculine and feminine. It is called John.

‘Joan, please.’

Its voice is sibilant. Its wrist is limp. Boss-woman laughs canned laughter at the correction, like she’s in some old sitcom. The woman-in-purple shrinks back in her chair, like she’s in a horror. ‘This is Eileen.’ Boss-woman works in a clockwise direction. ‘And that is Mary, knitting.’ The woman-in-dressing-gown is openly staring; her needles have ceased clicking. ‘Anya, in the corner.’ She points to where the woman-who-never-speaks sits, toes knotted like tree roots in the foot spa beneath her. ‘Jim, over there.’ He uses his book for cover. ‘And Harold, here.’ The other man—Nigerian or Jamaican—sucks his teeth loudly, deliberately.

‘Enchanté.’ The creature attempts a curtsy. It thinks it is a clown, obviously. It looks like one, certainly.

The man-in-uniform is alone in finding it funny. ‘I’m Craig. The deputy manager.’ He offers his hand to the creature. The creature raises the hand to its lips. The man-in-uniform thinks this hilarious.

Boss-woman’s look tells him to keep a lid on it. ‘Right, then... Joan. Let me show you to your room.’ As she leads the creature to the elevator, the only sound is of the spa bubbling between bunions. And as the elevator doors shut behind boss-woman, there is nuclear fission in the sitting room.

The woman-in-purple: ‘Is it a man or a woman?’

The Nigerian-Jamaican: ‘A moffie man!’

The woman-in-dressing-gown: ‘Mmm!?’

Jim stays silent. His eyes stay on the elevator. From where he sits, he cannot make out its digits, but he imagines their journey up to the first floor. He imagines her leading the creature down the carpeted corridor, past the cheap prints of ‘cheerful’ watercolours. He imagines her opening a door. And he is thinking that other man only just moved on and he is thinking it never takes them long and he is thinking please, no, not the room next to mine.

JOAN

Magnolia. Not the flower. Those I adore. End of winter and the branches still bare, it brings hope to this old heart to see their fleshy buds rise proud in the air: life is still there. But the colour. The colour. A yellowish-pinkish nothingness—how could anyone think it easy to live with? Not sure I shall manage it. Not for long at least. These walls will be the death of me!

The furnishings I can cover at least. Granny-goes-funky is how one might describe them. One of everything—the council have always prided themselves on providing the bare minimum. One armchair. That fabric in which I packaged my trinkets should sort it. One wardrobe, one chest of drawers. How I’ll get it all in there I don’t know, my dear. One single bed. Not been in one of them since I was fifteen and wanking up a storm on mother’s linen. One bedside cabinet. Which now has my record player perched atop it. I was particular with the porter about where it should be situated: I knew I should need it right from the outset; if I must unpack, I must have a soundtrack.

I plug in the player and—with only a little light swearing—locate the box containing my record collection. I’ve just dug out Callas—I do love a dead diva—when there’s a knock at the door. Am I not to be spared?

For one delicious moment, I deliberate not answering. But then I rally and ready myself for public consumption, à la Quentin. How very old-fashioned I recall Ms Crisp seeming, with her blue-rinsed witticisms, while we were out rallying for rainbow revolution. Now my own voice is every bit as querulous as hers once was. ‘Oh yes?’

The door opens of its own volition. They’ve a key to all of them. A Room of One’s Own this is not. ‘Room service!’ And in walks that dish—the assistant manageress. Sepia skin straining the seams of an ultramarine uniform. Carl? Colin? Reckon he’s one of the children—butch, but that blond hair is screaming.

‘I don’t remember ordering you in.’

His mouth opens. But his eyes are smiling. ‘No one round here remembers anything.’ Got a sense of humour on him. And a cup in each hand. ‘I see you’re settling in.’ He wends his way between boxes, some open and disgorging colorful contents upon cream carpeting.

‘It’s like home from home.’ I put aside the vinyl—more fun playing this one now.

‘Well don’t go blasting that this time of night. Old dears need their beauty sleep.’

I refocus on the wall behind him. There’s some cheap brassy thing, comes with the fittings. Like one needs