American Gothic E-Book

40,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: Blackwell Anthologies

- Sprache: Englisch

American Gothic remains an enduringly fascinating genre, retaining its chilling hold on the imagination. This revised and expanded anthology brings together texts from the colonial era to the twentieth century including recently discovered material, canonical literary contributions from Poe and Wharton among many others, and literature from sub-genres such as feminist and ‘wilderness’ Gothic.

- Revised and expanded to incorporate suggestions from twelve years of use in many countries

- An important text for students of the expanding field of Gothic studies

- Strong representation of female Gothic, wilderness Gothic, the Gothic of race, and the legacy of Salem witchcraft

- Edited by a founding member of the International Gothic Association

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 1668

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

Contents

List of Authors

Chronology

Thematic Table of Contents

Preface to the Second Edition

Editorial Principles

Acknowledgments

Introduction

Cotton Mather (1663–1728)

The Tryal of G. B. at a Court of OYER AND TERMINER, HELD IN SALEM, 1692

The Trial of Martha Carrier, at the COURT OF OYER AND TERMINER, HELD BY ADJOURNMENT AT SALEM, AUGUST 2, 1692

A Notable Exploit; wherein, Dux Faemina Facti [The Narrative of Hannah Dustan]

“Abraham Panther”

A surprising account of the Discovery of a Lady who was taken by the Indians in the year 1777, and after making her escape, she retired to a lonely Cave, where she lived nine years

J. Hector St. John de Crèvecoeur (1735–1813)

Letters from an American Farmer LETTER IX. DESCRIPTION OF CHARLES-TOWN; THOUGHTS ON SLAVERY; ON PHYSICAL EVIL; A MELANCHOLY SCENE

Charles Brockden Brown (1771–1810)

Somnambulism: A Fragment

Washington Irving (1783–1859)

The Legend of Sleepy Hollow. Found Among the Papers of the Late Diedrich Knickerbocker.

John Neal (1793–1876)

Idiosyncrasies

Nathaniel Hawthorne (1804–1864)

Alice Doane’s Appeal

Young Goodman Brown

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807–1882)

The Skeleton in Armor

Edgar Allan Poe (1809–1849)

Hop-Frog

The Cask of Amontillado

The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar

The Fall of the House of Usher

FIVE POEMS

Herman Melville (1819–1891)

The Bell-Tower

George Lippard (1822–1854)

from The Quaker City; or, The Monks of Monk Hall

Henry Clay Lewis (1825–1850)

A Struggle for Life

Rose Terry Cooke (1827–1892)

My Visitation

Emily Dickinson (1830–1886)

EIGHT POEMS

Louisa May Alcott (1832–1888)

A Whisper in the Dark

Harriet Prescott Spofford (1835–1921)

Her Story

Circumstance

Ambrose Bierce (1842–1914?)

An Inhabitant of Carcosa

The Death of Halpin Frayser

Henry James (1843–1916)

The Turn of the Screw

George Washington Cable (1844–1925)

Jean-Ah Poquelin

Madeline Yale Wynne (1847–1918)

The Little Room

Sarah Orne Jewett (1849–1909)

The Foreigner

Kate Chopin (1851–1904)

Désirée’s Baby

Mary E. Wilkins Freeman (1852–1930)

Old Woman Magoun

Luella Miller

Gertrude Atherton (1857–1948)

The Bell in the Fog

Anonymous (Folk Tale)

Talking Bones

Charles W. Chesnutt (1858–1932)

The Dumb Witness

The Sheriff’s Children

Charlotte Perkins Gilman (1860–1935)

The Giant Wisteria

The Yellow Wall-Paper

Elia Wilkinson Peattie (1862–1935)

The House That Was Not

Edith Wharton (1862–1937)

The Eyes

Robert W. Chambers (1865–1933)

In the Court of the Dragon

Edgar Lee Masters (1868–1950)

TWO POEMS

Edwin Arlington Robinson (1868–1935)

SIX POEMS

Frank Norris (1870–1902)

Lauth

Stephen Crane (1871–1900)

The Monster

Paul Laurence Dunbar (1872–1906)

The Lynching of Jube Benson

Alexander Posey (1873–1908)

Chinnubbie and the Owl

Jack London (1876–1916)

Samuel

H[oward] P[hillips] Lovecraft (1890–1937)

The Outsider

Select Bibliography

Index of Titles and First Lines

Index to the Introductions and Footnotes

“This is the definitive anthology of American Gothic tales, the one that offersthe most representative range of major authors and texts, in addition to excellent introductions and helpful annotations. All of this has only been enhanced in this second edition, since now there is an even wider range of important Gothic worksfor students and more advanced scholars to study and interpret. For readingand understanding the American Gothic short story, then, there is no better singlevolume anywhere.” —Jerrold E. Hogle, University of Arizona“This anthology is comprehensive and authoritative and will be an essential source for scholars and students for years to come. Professor Crow is to be congratulated for the meticulous care he has taken to introduce authors and for the extraordinary inclusiveness of the material selected.” — Andrew Smith, University of Sheffield“This new edition of Charles L. Crow’s anthology presents a panoramic overview of the American Gothic tradition from its Puritan origins to the 1930s Weird tale. One of the main strengths of the collection lies in the fact that it places, alongside the intelligent selections from authors already rightly well associated with the genre (figures such as Hawthorne, Poe, Brown, Irving, and James), contributions from lesser known figures such as George Lippard, John Neal, Charles W. Chesnutt, and Cotton Mather, to name but a few. This edition also benefits from a much greater acknowledgment of the traditionally overlooked contributions to the genre made by female authors: Crow selects not just obvious authors and poets such as Emily Dickinson, Charlotte PerkinsGilman, Louisa May Alcott, and Edith Wharton, but also the likes of Rose Terry Cooke, Harriet Prescott Spofford, Gertrude Atherton, and Madeline Yale Wynne. It is a development which, as Crow acknowledges in his preface, reflects the considerable amount of scholarly work that has been done in this area since the first version of the book was published.

Academics and students will find helpful other new additions such as the chronology (which collates relevant literary events with historical ones) and the thematic table of contents, which helpfully groups extracts under suggestive headings such as ‘Animals,’ ‘Children,’ ‘Cities,’ and ‘Feminist Themes,’ thereby facilitating a rewarding cross-pollination of authors and texts that might not otherwise be considered alongside one another. The anthology’s thoughtful selection of texts and authors, and practical scholarly apparatus, mean that it should be an immensely useful resource for anyone teaching on courses related to this ever-expanding and influential subsection of American literary studies.” — Bernice Murphy, Trinity College Dublin

This second edition first published 2013Editorial material and organization © 2013 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Edition history: Blackwell Publishers Ltd (1e, 1999)

Wiley-Blackwell is an imprint of John Wiley & Sons, formed by the merger of Wiley’s global Scientific, Technical and Medical business with Blackwell Publishing.

Registered OfficeJohn Wiley & Sons, Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK

Editorial Offices350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UKThe Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK

For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services, and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley-blackwell.

The right of Charles L. Crow to be identified as the author of the editorial material in this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books.

Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book. This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold on the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

American gothic : From Salem witchcraft to H. P. Lovecraft, An Anthology / edited by Charles L. Crow. – Second edition.pages cmPrevious edition: American gothic : an anthology, 1787–1916. Malden, Mass. : Blackwell, 1999.Includes bibliographical references and indexes.

ISBN 978-0-470-65980-9 (cloth) – ISBN 978-0-470-65979-3 (pbk.) 1. American literature. 2. Gothic revival (Literature)–United States. 3. Supernatural–Literary collections. 4. Horror tales, American. 5. Fantasy literature, American. 6. Fear–Literary collections. I. Crow, Charles L.PS507.A56 2013810.8–dc23

2012016772

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

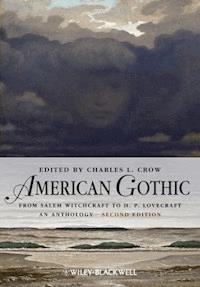

Cover image: Elihu Vedder, Memory, 1870. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Mr and Mrs William Preston Harrison Collection 33.11.1. © 2012 Digital image Museum Associates / LACMA / Art Resource NY / Scala, Florence.Cover design: Richard Boxall Design AssociatesOrnament image © Keith Bishop / iStockphoto

List of Authors

Louisa May Alcott (1832–1888)

Gertrude Atherton (1857–1948)

Ambrose Bierce (1842–1914?)

Charles Brockden Brown (1771–1810)

George Washington Cable (1844–1925)

Robert W. Chambers (1865–1933)

Charles W. Chesnutt (1858–1932)

Kate Chopin (1851–1904)

Rose Terry Cooke (1827–1892)

Stephen Crane (1871–1900)

J. Hector St. John de Crèvecoeur (1735–1813)

Emily Dickinson (1830–1886)

Paul Laurence Dunbar (1872–1906)

Mary E. Wilkins Freeman (1852–1930)

Charlotte Perkins Gilman (1860–1935)

Nathaniel Hawthorne (1804–1864)

Washington Irving (1783–1859)

Henry James (1843–1916)

Sarah Orne Jewett (1849–1909)

Henry Clay Lewis (1825–1850)

George Lippard (1822–1854)

Jack London (1876–1916)

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807–1882)

H[oward] P[hillips] Lovecraft (1890–1937)

Edgar Lee Masters (1868–1950)

Cotton Mather (1663–1728)

Herman Melville (1819–1891)

John Neal (1793–1876)

Frank Norris (1870–1902)

“Abraham Panther” (?)

Elia Wilkinson Peattie (1862–1935)

Edgar Allan Poe (1809–1849)

Alexander Posey (1873–1908)

Edwin Arlington Robinson (1869–1935)

Harriet Prescott Spofford (1835–1921)

Edith Wharton (1862–1937)

Madeline Yale Wynne (1847–1918)

Chronology

Date

Literary Event

Historical Event

1663

Cotton Mather b.

1689

Mather, Memorable Provinces, Relating to Witchcrafts and Possessions

1692

Salem Witch trials begin

1693

Mather, The Wonders of the Invisible World

Witch trials end

1702

Mather, Magnalia Christi Americana

1728

Cotton Mather d.

1735

J. Hector St. John de Crèvecoeur b.

1771

Charles Brockden Brown b.

1776

United States Declaration of Independence

1787

Anon., “An Account of a Beautiful Young Lady”

1794

William Godwin, Caleb Williams

1798

Brown, Wieland

1799

Brown, Arthur Mervyn, Ormond, Edgar Huntly

1782

Crèvecoeur, Letters from an American Farmer

1783

Washington Irving b.

1787

U.S. Constitution signed

1793

John Neal b.

1803

Louisiana Purchase

1804

Nathaniel Hawthorne b.

1807

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow b.

1809

Edgar Allan Poe b.

1810

Charles Brockden Brown d.

1812

War with Britain

1813

J. Hector St. John de Crèvecoeur d.

1818

Mary Shelley, Frankenstein

1819

Irving, The Sketch Book begins serial publication

Herman Melville b.

1820

Missouri Compromise

1822

George Lippard b.

1825

Henry Clay Lewis b.

1827

Rose Terry Cooke b.

1830

Indian Removal Act signed

Emily Dickinson b.

1831

Poe, Poems by Edgar A. Poe

1832

Louisa May Alcott b.

1835

Harriet Prescott Spofford b.

1836

Ralph Waldo Emerson, Nature

1837

Hawthorne, Twice-Told Tales

1838

Poe, The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym

1840

Poe, Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque

1841

Longfellow, Ballads and Other Poems

1842

Ambrose Bierce b.

1843

Henry James b.

1844

Lippard, The Quaker City; or, the Monks of Monk Hall

George Washington Cable b.

1845

Poe, Tales

Poe, The Raven and Other Poems

1846

Hawthorne, Mosses from an Old Manse

1847

Madeline Yale Wynne b.

1848

Gold discovered in California

1849

Edgar Allan Poe d.

Sarah Orne Jewett b.

1850

Hawthorne, The Scarlet Letter

Harper’s New Monthly Magazine founded

Henry Clay Lewis d.

Lewis, Odd Leaves from the Life of a Louisiana Swamp Doctor

1851

Melville, Moby-Dick

Hawthorne, House of the Seven Gables

Kate Chopin b.

1852

Hawthorne, The Blithedale Romance

Melville, Pierre

Mary E. Wilkins Freeman b.

1854

George Lippard d.

1856

Melville, Piazza Tales

1857

Melville, The Confidence Man

Dred Scott decision by Supreme Court

Atlantic Monthly founded

Gertrude Atherton b.

1858

Cooke, “My Visitation”

Charles W. Chesnutt b.

1859

Charles Darwin, The Origin of Species

John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry

Washington Irving d.

1860

Hawthorne, The Marble Faun

Abraham Lincoln elected

Spofford, “Circumstance”

Charlotte Perkins Gilman b.

1861

Civil War begins

1862

Elia Wilkinson Peattie b.

Edith Wharton b.

1863

Alcott, “A Whisper in the Dark”

1864

Nathaniel Hawthorne d.

1865

Civil War ends

Lincoln assassinated

Robert W. Chambers b.

1868

Alcott, Little Women, v. 1

Edgar Lee Masters b.

1868

Edwin Arlington Robinson b.

1869

Alcott, Little Women, v. 2

1870

Frank Norris b.

1871

Stephen Crane b.

1872

Spofford, “Her Story”

Paul Laurence Dunbar b.

1873

Alexander Posey b.

1876

Jack London b.

Battle of Little Big Horn

Philadelphia Exposition

John Neal d.

1877

President Hayes ends Southern Reconstruction

1879

G. W. Cable, Old Creole Days

1880

Cable, The Grandissimes

1882

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow d.

1884

Mark Twain, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

1886

Bierce, “An Inhabitant of Carcosa”

Haymarket Riot in Chicago

Emily Dickinson d.

1888

Louisa May Alcott d.

1890

H[oward] P[hillips] Lovecraft b.

1891

Bierce, “The Death of Halpin Frayser”

Herman Melville d.

Gilman, “The Giant Wisteria”

1892

Bierce, Black Beetles in Amber

Rose Terry Cooke d.

Gilman, “The Yellow Wallpaper”

1893

Fran Norris, “Lauth”

Major Depression begins

Columbian Exposition in Chicago

1894

Twain, The Tragedy of Pudd’nhead Wilson

1895

Chambers, The King in Yellow

Wynne, “The Little Room”

1896

Jewett, The Country of the Pointed Firs

1897

E. A. Robinson, Children of the Night

Bram Stoker, Dracula

1898

James, The Turn of the Screw

Spanish–American War

Peattie, “The House That Was Not”

1899

Bierce, Fantastic Fables

Chesnutt, The Conjure Woman, The Wife of His Youth

Crane, “The Monster”

Norris, McTeague

1900

Chesnutt, The House Behind the Cedars

Stephen Crane d.

1901

Chesnutt, The Marrow of Tradition

McKinley assassinated

T. Roosevelt president

1902

Chesnutt, The Colonel’s Dream

Frank Norris d.

1904

Dunbar, The Heart of Happy Hollow

Kate Chopin d.

1905

Atherton, The Bell in the Fog and Other Stories

1906

Paul Laurence Dunbar d.

1908

Alexander Posey d.

1909

Sarah Orne Jewett d.

1910

Wharton, “The Eyes”

Mexican Revolution begins

1911

Wharton, Ethan Frome

1914

Norris, Vandover and the Brute

World War I begins

1915

Masters, Spoon River Anthology

1916

Robinson, The Man Against the Sky

Henry James d.

Jack London d.

Ambrose Bierce d.?

1917

Russian Revolution begins

1918

World War I ends

Madeline Yale Wynne d.

1920

Robinson, The Three Taverns

Mexican Revolution ends

1921

Harriet Prescott Spofford d.

1925

Robinson, Dionysus in Doubt

George Washington Cable d.

1926

Lovecraft, “The Outsider”

1930

Mary E. Wilkins Freeman d.

1932

Charles W. Chesnutt d.

1933

Robert W. Chambers d.

1935

Charlotte Perkins Gilman d.

Elia Wilkinson Peattie d.

Edwin Arlington Robinson d.

1937

H. P. Lovecraft d.

Edith Wharton d.

1948

Gertrude Atherton d.

1950

Edgar Lee Masters d.

1955

Thomas H. Johnson (ed.), The Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson

1967

Richard M. Dorson (ed.), American Negro Folktales

Thematic Table of Contents

American Indians

Animals

Children (see alsoFamilies, Incest)

Cities

Degeneration and Atavism

Disease, Doctors, and Medicine

Doubles

Dreams and Nightmares

Families (see alsoChildren, Incest)

Feminist Themes

Folklore

Friendship and Same-Sex Love

Ghosts, Demons, and Vampires (see alsoHaunted Houses or Castles)

Haunted Houses or Castles(see alsoGhosts, Demons, and Vampires)

Imprisonment (see alsoLawyers and the Law)

Incest (see alsoFamilies, Children)

Insanity(see alsoDisease, Doctors, and Medicine)

Lawyers and the Law(see alsoImprisonment)

Monsters

Murder

New England Gothic

Race and Slavery

Revenge

Ruins

Satan and Evil Gods

Southern Gothic

Suicide

Terror and Gothic Theory

Tombs

Village Life

Wilderness, Frontier, and the Natural World

Witchcraft

Preface to the Second Edition

The first edition of this volume appeared in 1999. In the intervening period of more than a decade, Gothic studies has grown as an academic discipline, in large part due to work by members of the International Gothic Association, which celebrated the twentieth anniversary of its founding at its 2011 convention in Heidelberg.

In American Gothic specifically, classes and seminars in the field, once rare, now are found in universities throughout the United States and in many other countries.

In recent years, researchers have combed through periodicals of the nineteenth century and have uncovered a rich trove of Gothic texts, many by women authors. Many recent studies, as represented by this edition’s bibliography, have sharpened our historical and critical understanding of American Gothic. This second edition reflects the growth of this scholarship and the experiences of students and teachers who have used the book, many of whom have made helpful suggestions.

Editorial Principles

Sources are given for each text. Wherever possible the exact spelling and punctuation of the original are retained, even (and especially) in the case of eccentric usage by writers like Emily Dickinson. Original spelling and punctuation are retained also for the oldest works, those by Cotton Mather. In a few instances obvious errors have been corrected, and this has been stated in the headnote.

Words that may be unfamiliar but can be checked in a desk dictionary usually are not footnoted. Words that are less accessible, potentially misleading to the contemporary reader, or in dialect or a foreign language are footnoted, as are literary and biblical allusions, where possible.

Acknowledgments

In the years since the first edition of this book, I have benefited from collegial discussions with members of the International Gothic Association, of whom I would like to mention especially Jerrold E. Hogle (who first suggested this anthology), David Punter, William Hughes, Andrew Smith, John Whatley, Zofia Kolbuszewska, and the late Allan Lloyd-Smith.

A number of scholars have made suggestions for this edition, or have helpfully answered my queries. Among them are Chad Rohman, Carol Siegel, Jeffrey Andrew Weinstock, Cynthia Kuhn, Matthew W. Sivils, Bernice M. Murphy, and Sherry Truffin. Wiley-Blackwell’s reviewers for this revised edition made useful comments, most of which have been incorporated.

My graduate students at Bowling Green State University were among the first users of the 1999 edition. Though more than a decade has passed, those discussions are remembered and have influenced the evolution of our text. I would like to recognize the contributions particularly of Katherine Harper and Julia Shaw.

In my acknowledgments to the first edition, I thanked Cynthia, Jon, and Sarah Crow “for keeping the Editor from sinking too deeply into Gothic gloom.” That gratitude needs to be repeated, and extended to new members of the family, Joan Lau and Raphael, Fiona and Jacob Goldman.

The following publishers have granted permission to reprint material under copyright:

Poems by Emily Dickinson reprinted by permission of the publishers and the Trustees of Amherst College from The Poems of Emily Dickinson: Variorum Edition, edited by Ralph W. Franklin (Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press), Copyright © 1998 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. Copyright © 1951, 1955, 1979, 1983 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College.

Duke University Press for Charles Chesnutt, “The Dumb Witness,” in The Conjure Woman and Other Conjure Tales, edited by Richard Broadhead, pp. 158–71. Copyright © 1993, Duke University Press. All rights reserved. Reprinted by permission of the publisher. www.dukeupress.edu.

Alexander Posey’s “Chinnubbie and the Owl” reprinted with permission from the Alexander Posey Collection, Gilcrease Museum Archives, University of Tulsa. Flat Storage. Registration #4627.33.

H. P. Lovecraft’s “The Outsider” Copyright 1926 and renewed © 1963 by August Derleth and Donald Wandrei. Reprinted by permission of Arkham House Publishers, Inc., and Arkham’s agents, JABerwocky Literary Agency, Inc., PO Box 4558, Sunnyside NY 11104-0558.

Introduction

The Gothic is a larger and more important part of the literature of the United States than is generally thought. It has been so since colonial days, and has been used to explore serious issues. And much of the country’s literature is Gothic: it is not an obscure area, but includes some of its best-known works and authors. Moby-Dick is Gothic; so are many of the poems of Emily Dickinson; so are The Sea Wolf, Absalom, Absalom!, Native Son, and Beloved. So are films as diverse as Alien, Lone Star, Sling Blade, and Winter’s Bone.

Clearly some definitions are needed to support these claims. We begin with a distinction. The supernatural is permitted but not essential to the Gothic. Mysterious events and shadowy beings have had a continuous presence in this tradition, from early English Gothic romances to the latest thriller by Stephen King or the last installment in Anne Rice’s vampire saga; but they are not essential. Nor is there any particular setting required by the Gothic, in spite of the prevalence of big old houses, claustrophobic rooms, and dark forests. A whaling ship can be a suitable Gothic site as well as a castle. Poe observed that “terror is not of Germany, but of the soul,” and his observation points us in the right direction, and away from the stage props.

What, then, are the qualities of the Gothic? Most definitions divide into two approaches, and either address the response of the reader or the characters and events within the work. Certainly most readers understand that the Gothic generates fear, or something like fear. We feel a certain chill at some point, as we encounter a Gothic work. This emotional response – what takes place in the soul, as Poe terms it – is in some way the point of the Gothic experience, and is, paradoxically, a source of pleasure. “’Tis so appalling – it exhilarates,” as Emily Dickinson puts it. The thrill can be mindless, like that of riding a roller-coaster, and can be satisfied by manipulation of formulas by skilled popular authors or film makers. Yet moments of fear can also be moments of imaginative liberation, and of recognition. In the Gothic, taboos are often broken, forbidden secrets are spoken, and barriers are crossed. The key moment in a Gothic work will occur at the point of boundary crossing or revelation, when something hidden or unexpressed is revealed, and we experience the shock of an encounter which is both unexpected and expected. If we think, and perhaps scream, No! then another part of our mind may be acknowledging: Yes, that is it!

Within a Gothic work, there is usually a confusion of good and evil, as conventionally defined. We may be asked to suspend our usual patterns of judgment. A frequently encountered character combines and blurs the roles of hero and villain. Captain Ahab, the “grand ungodly godlike man,” is a model of the Gothic villain-hero. But Gothic characters occur in small and private worlds as well. In our collection, Old Woman Magoun is both a kindly, nurturing grandmother and a child murderer. The governess of Henry James’s famously ambiguous novella The Turn of the Screw may be a heroic defender of her pupils or a lunatic.

American writers understood, quite early, that the Gothic offered a way to explore areas otherwise denied them. The Gothic is a literature of opposition. If the national story of the United States has been one of faith in progress and success and in opportunity for the individual, Gothic literature can tell the story of those who are rejected, oppressed, or who have failed. The Gothic has provided a forum for long-standing national concerns about race, that great and continuing issue that challenges the national myth. In this collection, for example, a number of stories about monsters objectify racial fear and hatred, and the largely forbidden topic of miscegenation is explored by several authors. If the national myth was of equality, a society in which class (like race) does not matter, the Gothic could expose, in stories about brutes, the real class anxiety present in periods of emigration and economic flux. Similarly, in an age when gender roles were shifting, sexual difference could be a source of fear. This anxiety was further heightened by an epidemic of sexually transmitted disease, another forbidden topic of the age. Scholar Elaine Showalter has suggested that this issue underlies the popularity of vampires in Victorian fiction. In any case, the Gothic has been especially congenial to women authors, who found in it ways to explore alternative visions of female life, power, and even revenge. Similarly, homophobia and homoeroticism could be approached within the Gothic when overt discussion was impossible. If the dominant national story was about progress, and a part of this set of values was faith in science and technology to improve everyone’s life, then the Gothic can expose anxiety about what the scientist might create, and what threats might be posed by machines, if they escape our control. While we want to believe in wholesome families, the Gothic can expose what many may know about, and never acknowledge: the hatred that can exist alongside of love, the reality of child abuse, even incest.

In all of these areas, then, Gothic explores frontiers: between races, genders, and classes; people and machines; health and disease; the living and the dead; and the boundary of the closed door. It has enabled a dialog to exist instead of a single story, and has given a voice to people, and fears, otherwise left silent.

This volume attempts to show the breadth of the American Gothic tradition. Authors long understood to practice the Gothic, like Poe and Hawthorne, are of course represented. But the reader will find familiar authors who are seldom defined as Gothic, such as Stephen Crane and Jack London. Little-known authors – some of them unjustly obscure – are represented as well as familiar and famous names. Moreover, since it is our intention to stretch the definition of the Gothic, the reader will encounter works which are subtly Gothic; that is, which reveal their Gothic elements slowly, or upon reflection, or in hybrid form with other modes of discourse.

We begin with the Puritan divine and historian Cotton Mather. Mather certainly did not consider himself a Gothic writer. Indeed, the term would have been meaningless to him. Nonetheless, the two selections from Mather represent two of the foundations of American Gothic: the “Matter of Salem” (the witch trials of 1692–3) so important to later writers like Hawthorne; and the Indian captivity narrative, a distinctive American form that shaped the Gothic of American wilderness.

Our collection ends, more than two hundred years later, with stories and poems that carry American Gothic into the modern age.

Cotton Mather(1663–1728)

The Tryal of G. B. at a Court of OYER AND TERMINER, HELD IN SALEM, 1692

GLAD should I have been, if I had never known the Name of this Man; or never had this occasion to mention so much as the first Letters of his Name. But the Government requiring some Account of his Trial to be inserted in this Book, it becomes me with all Obedience to submit unto the Order.

Yea, there were two Testimonies, that G. B. with only putting the Fore Finger of his Right Hand into the Muzzle of an heavy Gun, a Fowling-piece of about six or seven foot Barrel, did lift up the Gun, and hold it out at Arms-end; a Gun which the Deponents thought strong Men could not with both hands lift Up, and hold out at the But-end, as is usual. Indeed, one of these Witnesses was over-perswaded by some Persons, to be out of the way upon G. B’s Tryal, but he came afterwards with Sorrow for his withdraw, and gave in his Testimony: Nor were either of these Witnesses made use of as Evidences in the Trial.

The Trial of Martha Carrier, at the COURT OF OYER AND TERMINER, HELD BY ADJOURNMENT AT SALEM, AUGUST 2, 1692

MARTHA CARRIER was Indicted for the bewitching certain Persons, according to the Form usual in such Cases, pleading Not Guilty, to her Indictment; there were first brought in a considerable number of the bewitched Persons; who not only made the Court sensible of an horrid Witchcraft committed upon them, but also deposed, That it was Martha Carrier, or her Shape, that grievously tormented them, by Biting, Pricking, Pinching and Choaking of them. It was further deposed, That while this Carrier was on her Examination, before the Magistrates, the Poor People were so tortured that everyone expected their Death upon the very spot, but that upon the binding of Carrier they were eased. Moreover the Look of Carrier then laid the Afflicted People for dead; and her Touch, if her Eye at the same time were off them, raised them again: Which Things were also now seen upon her Tryal. And it was testified, That upon the mention of some having their Necks twisted almost round, by the Shape of this Carrier, she replyed, Its no matter though their Necks had been twisted quite off.